Trumbull traveled up and down the Eastern Seaboard to paint the members of the Continental Congress from life.

Painting the Declaration of Independence

These members of the Continental Congress were painted from life.

by DR. BRYAN ZYGMONT

Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\): John Trumbull, The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776, 1786–1820, oil on canvas, 20 7/8 x 31 inches / 53 x 78.7 cm (Yale University Art Gallery)

Like many artists of the early-Federal period (c. 1789-1801), the name John Trumbull is not one immediately recognized by most Americans. Yet despite this fact, the majority of Americans are well aware of many of Trumbull’s most famous paintings. Trumbull’s portrait of the first Secretary of the Treasury , Alexander Hamilton, has long graced the ten-dollar bill. Although Trumbull made a career as a portraitist, his real ambition lay in the painting of larger, more ambitious historical compositions. Without doubt, the one that is most frequently reproduced in elementary school history textbooks is The Declaration of Independence, a painting that exists in two versions. The first is smaller in size and is part of the Yale University Art Gallery (above) while the second is the monumental version currently on display in the Capitol Rotunda (below).

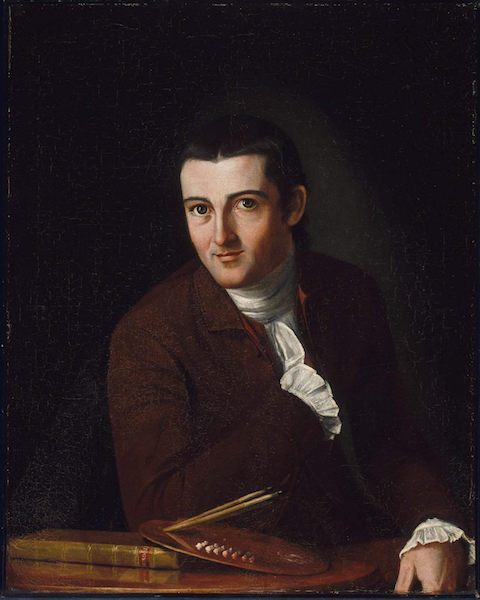

Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\): John Trumbull, Self-portrait, 1777, oil on canvas, 76.83 x 61.28 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Family history

Yet to understand this composition, one must first grapple with Trumbull’s complicated history and personality. He was the sixth and youngest child of Jonathan Trumbull and Faith Robinson. If there was an aristocracy in colonial New England, Trumbull was born into it. His Harvard-educated father was a representative to the Connecticut General Assembly. Later he served as the Governor of Connecticut Colony (1769-1776) and then after the War of American Independence, as the Governor of the state of Connecticut (1776-1784). The artist’s mother was a direct descendant of John Robinson, the so-called “Pastor to the Pilgrim-Fathers” before they sailed on the Mayflower for the New World. Given his prestigious family legacy, Trumbull the Elder had little interest in allowing Trumbull the Younger to pursue a career as a painter. Instead, Governor Trumbull sent the artist-to-be to Harvard College so that his son could find a more useful vocation in either the law or the ministry.

However, in 1772, Trumbull made a social call to the artist John Singleton Copley who was then still in Boston—just a short distance from Cambridge. When writing his autobiography almost half a century later—in 1841—Trumbull still remembered this meeting with great clarity:

We found Mr. Copley dressed to receive a party of friends at dinner. I remember his dress and appearance—an elegant looking man, dressed in a fine maroon cloth, with gilt buttons—this was dazzling to my unpracticed eye!—but his paintings, the first I had ever seen deserving the name, riveted, absorbed my attention, and renewed all my desire to enter upon such a pursuit. But my destiny was fixed, and the next day I went to Cambridge, passed my examination in fro, and was readily admitted to the Junior class.

Autobiography, Reminiscences and Letters of John Trumbull, from 1756 to 1841

There was, of course, no art major at Harvard during the eighteenth century, so Trumbull studied art in his free time, copying and sketching works of art that hung on the college’s walls. He also learned from books he was able to borrow from the college’s library. He graduated in 1773 and became one of the few artists in the history of early American art to complete a college education.

The army

Trumbull’s graduation from Harvard took place during a tumultuous period in American history, and Trumbull wished to secure a commission as an officer in the Continental Army. His brother, Joseph, was the Commissary General of the Army, and likely suggested that his younger brother draw a plan of the British army’s position at Boston Neck to present to General Washington as a way of introduction. Shortly thereafter, Washington appointed Trumbull as an aide-de-camp (a confidential assistant to a senior officer). The following year, in the spring of 1776, Major General Horatio Gates appointed Trumbull deputy adjutant-general (military chief administrative officer) at the rank of Colonel. Alas, Trumbull resigned his commission less than a year later because of a minor squabble with Congress as to the date of the commission. Yet despite being Colonel John Trumbull for little more than a year, the artist carried the honorific title of Colonel for the remainder of his life. His 1841 autobiography, for example, was entitled—not immodestly—The Autobiography of Colonel John Trumbull.

However, it was because of his (admittedly, very limited) military experience that John Trumbull believed that he was uniquely qualified to pictorially depict the major events of the American Revolutionary War. His first step, was to seek out some artistic training, and in this endeavor, he followed in the footsteps of many artists before him (and, for that matter, after him): he sailed for London and Benjamin West’s studio (West was an American artist with a successful career in London). The year was 1780, and the War of Independence was still in full swing, although nearing its completion. It must have caused suspicion that a former officer in the Continental Army has arrived in London to study painting, particularly because Benjamin West, as the official history painter to the court, had the ear and confidence of King George.

Politics

In West’s studio, Trumbull met Gilbert Stuart, who was perhaps West’s most accomplished pupil. But Stuart and Trumbull differed in some key ways. First, Stuart always knew that portraiture would occupy most of his artistic efforts when he returned across the Atlantic Ocean, while Trumbull had the higher aspiration to paint historical compositions. More importantly, perhaps, Stuart largely kept his political beliefs during this vitriolic period to himself, while Trumbull—both in letters home and in his personal interactions about London—was decidedly anti-British. People began to notice, and on 20 November 1780, Colonel John Trumbull was arrested and charged with treason. He was imprisoned for more than 8 months and released only after powerful friends—Benjamin West and the statesman Edmund Burke among others—appealed to the Privy Council for the artist’s release. This was granted on 12 June 1781, and Trumbull was given 30 days to exit Great Britain.

Connecticut and back to London

Trumbull returned to Connecticut for two years, and during that time his father again attempted to convince him to pursue another more profitable vocation. Undeterred, Trumbull returned to London and the warmth of West’s studio in January of 1784. West set forth a rigorous course of study. Trumbull woke at five o’clock in the morning to study human anatomy. After breakfast several hours later, he painted for the rest of the day. His evening was capped by studying at the Royal Academy of Art. The aspiring artist made quick and steady progress. When writing to his brother Jonathan in September of 1784, for example, Trumbull remarked, “I have the pleasure to find that my labour is not in vain, & to hear Judges of the Art declare that I have made a more rapid progress in the few months I have been here than they have before known.”

Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\): John Trumbull, The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, 17 June, 1775, after 1815-before 1831, oil on canvas, 50.16 x 75.56 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The history of our country

Growing in confidence, Trumbull was determined to return to the newly formed United States with paintings that would commemorate the recent victory over Great Britain. Writing to his father—whose approval, it seems, he still sought—Trumbull explained in March of 1785,

the great object of my wishes…is to take up the History of Our Country, and paint the principal Events particular of the late War.

As quoted in American paintings of the eighteenth century (National Gallery of Art, 1995)

By the end of the year, Trumbull had already begun work on two paintings of the series, images known to generations of American elementary school students because of their inclusion in history textbooks: The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker’s Hill, June 17, 1775 (above) and The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec, December 31 1775 (below). In 1786, Trumbull began to plan three other Revolutionary War paintings: The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777, The Capture of the Hessians at Trenton, December 26, 1776, and The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, October 19, 1781. Interestingly, all five of these compositions are, essentially, scenes of battlefields.

Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\): John Trumbull, The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec, December 31, 1775, 1786, oil on canvas, 62.5 x 94 cm (Yale University Art Gallery)

The Declaration of Independence

In July of 1786, however, Trumbull accepted Thomas Jefferson’s invitation to visit Paris, and he brought Bunker’s Hill and the Attack on Quebec with him. Jefferson, then the United States Ambassador to France, and a bit of artist himself, managed to convince Trumbull that he should turn his artistic talents towards a scene involving the Declaration of Independence. While in Paris, Trumbull began to sketch out the composition, taking into account Jefferson’s memory of the event and the [diplomat’s own sketch](http://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/2805) of the Assembly Room in the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia where the Declaration of Independence was first presented to Congress and subsequently signed.

Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\): John Trumbull, The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776, 1818 (placed 1826), oil on canvas, 12′ x 18′ (Rotunda, U.S. Capitol)

The painting that resulted from this collaboration between artist and politician has become one of the most famous images in the history of American art. It can be found on the back of the (seldom used) $2 bill, and has graced American postage stamps. And yet, what the painting depicts is often misunderstood. Trumbull himself called this painting The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776. However, this is inaccurate; this painting depicts not the signing of the document, but instead the presentation of a draft of it to Congress on 28 June 1776. Our attention begins with the five men standing in the middle of the painting, the so-called Committee of Five that was primarily responsible for the written document. They are—from left to right—John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Robert R. Livingston of New York, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, and Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania. Clearly, the red-headed Jefferson is the most important, for he alone holds the document that he presents to John Hancock, the President of the Continental Congress, who sits behind the desk.

Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\): The so-called Committee of Five, from left to right—John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Robert R. Livingston of New York, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, and Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania (detail), John Trumbull, The Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776, 1786–1820, oil on canvas, 20 7/8 x 31 inches / 53 x 78.7 cm (Yale University Art Gallery)

Of the five men standing, Trumbull was able to paint three of them—Adams, Jefferson, and Franklin—from life and directly onto the canvas prior to departing from Europe. When the artist returned to the United States in 1789, he spent several years traveling up and down the eastern seaboard so that he could paint portraits from life. This was not always possible, however, and in 1817—some 27 years later, Trumbull was still at work on what would become his most famous image. He wrote to Jefferson that year to inform the former president as to the progress he had made on this relatively small—21” x 31”—image:

The picture will contain Portraits of at least Forty Seven Members:—for the faithful resemblance of Thirty Six I am responsible, as they were done by myself from the Life, being all who survived in the year 1791. Of the Remainder, Nine are from Pictures done by others:—one Gen[era]l Whipple of New Hampshire is from Memory: and one Mr. Ben. Harrison of Virginia is from description, aided by memory.

As quoted in The Republic in Print (Columbia University Press, 2007)

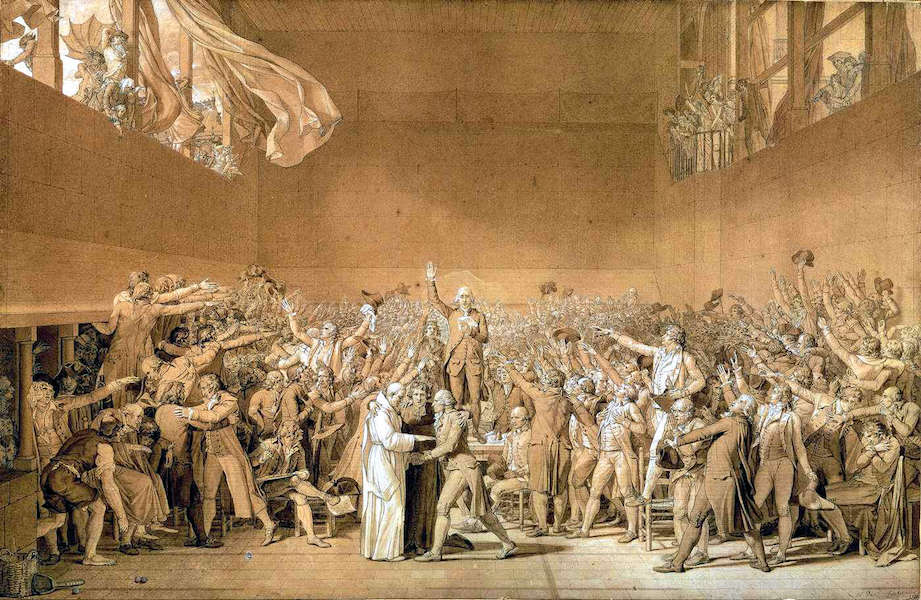

To compare this image to those Trumbull began at the same time—the battle paintings of the Revolutionary War Series—is interesting, for while some of those are dynamic and filled with drama, The Declaration of Independence is, at its essence, a static—some might claim pictorially boring—image of a group of seated men looking at a group of standing men. Indeed, other artists—Jacques-Louis David comes to mind—were able to conceive a way to depict a similar event in a visually engaging way. David’s sketch for the Oath of the Tennis Court (below, depicting one of the first events of the French Revolution), for example, is far more dynamic and dramatic than is Trumbull’s painting.

Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\): Jacques Louis David, The Oath of the Tennis Court, 1791, pen and brown ink, brown wash with white highlights, 66 x 101 cm (Palace of Versailles)

But this seemed not to matter to Trumbull, nor did it bother many members of Congress, for on 17 January 1817 they approved—by an overwhelming 150-50 majority—a proposal to commission Trumbull to complete four paintings for the Great Rotunda of the as yet uncompleted Capitol Building. Increasing the size of The Declaration of Independence to 12’x18’ did little to enhance its dynamism. In 1828, for example, John Randolph of Virginia wrote,

the Declaration of Independence [ought] to be called the Shin-piece, for surely never was there before such a collection of legs submitted to the eyes of man.

As quoted in A Centre of Wonders: The Body in Early America (Cornell University Press, 2018)

Still others criticized the lack of accuracy in the room and furnishings, and, as importantly, as to who was actually present when the document was presented.

But these concerns were of little bother to Trumbull, who had become one of the most powerful voices—if not one of the more skilled paintbrushes—in American art during the first half of the nineteenth century. Indeed, Trumbull served as the President of the conservative American Academy of Fine Arts from 1817 until 1836. Without doubt, this position helped him receive the prestigious congressional commission in 1817 and allowed him to exert considerable influence over the direction of American art during the end of his career. Moreover, his autobiography—written just two years prior to his death—provided the opportunity to explain his (perhaps exaggerated) importance within American art. While the Declaration of Independence might not be the most interesting work within the history of American painting, it certainly is one of the most recognizable. Trumbull, no doubt, would approve of this.

Go deeper

This painting at the Yale Art Gallery

This painting at the U.S. Capitol