11.3: North America c. 1500 - 1900 (I)

- Page ID

- 67097

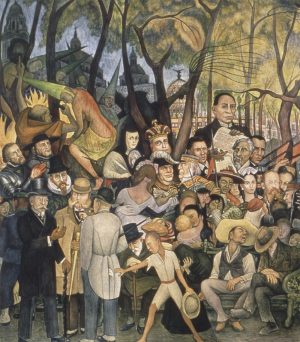

North America c. 1500 – 1900

From the colonization of the new world to revolution, and independence.

Native North American art, c. 1500 – today

“Native American art” generally refers to peoples in what is today the United States and Canada.

c. 1500 - present

A beginner's guide

Terms and Issues in Native American Art

Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Connecticut, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, the Dakotas, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Utah, Wisconsin, Wyoming—all state names derived from Native American sources. Pontiac, moose, raccoon, pecan, kayak, squash, chipmunk, Winnebago. These common words also derive from different Native words and demonstrate the influence these groups have had on the United States.Pontiac, for instance, was an 18th century Ottawa chief (also called Obwandiyag), who fought against the British in the Great Lakes region. The word “moose,” first used in English in the early seventeenth century during colonization, comes from Algonquian languages.

Stereotypes

Stereotypes persist when discussing Native American arts and cultures, and sadly many people remain unaware of the complicated and fascinating histories of Native peoples and their art. Too many people still imagine a warrior or chief on horseback wearing a feathered headdress, or a beautiful young “princess” in an animal hide dress (what we now call the Indian Princess). Popular culture and movies perpetuate these images, and homogenize the incredible diversity of Native groups across North America. There are too many different languages, cultural traditions, cosmologies, and ritual practices to adequately make broad statements about the cultures and arts of the indigenous peoples of what is now the United States and Canada.

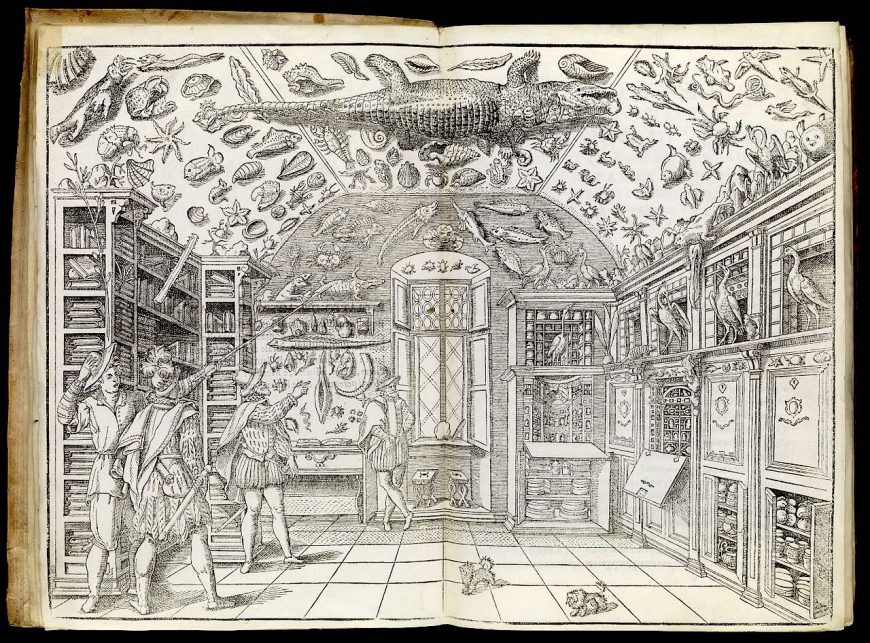

In the past, the term “primitive” has been used to describe the art of Native tribes and First Nations. This term is deeply problematic—and reveals the distorted lens of colonialism through which these groups have been seen and misunderstood. After contact, Europeans and Euro-Americans often conceived of the Amerindian peoples of North America as noble savages (a primitive, uncivilized, and romanticized “Other”). This legacy has affected the reception and appreciation of Native arts, which is why much of it was initially collected by anthropological (rather than art) museums. Many people viewed Native objects as curiosities or as specimens of “dying” cultures—which in part explains why many objects were stolen or otherwise acquired without approval of Native peoples. Many sacred objects, for example, were removed and put on display for non-Native audiences. While much has changed, this legacy lives on, and it is important to be aware of and overcome the many stereotypes and biases that persist from prior centuries.

Repatriation

One significant step that has been taken to correct some of this colonial legacy has been NAGPRA, or the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1992. This is a U.S. federal law that dictates that “human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony, referred to collectively in the statute as cultural items” be returned to tribes if they can demonstrate “lineal descent or cultural affiliation.” Many museums in the U.S. have been actively trying to repatriate items and human remains. For example, in 2011, a museum returned a wooden box drum, a hide robe, wooden masks, a headdress, a rattle, and a pipe to the Tlingít T’akdeintaan Clan of Hoonah, Alaska. These objects were purchased in 1924 for $500.

In the 19th century, many groups were violently forced from their ancestral homelands onto reservations. This is an important factor to remember when reading the essays and watching the videos in this section because the art changes—sometimes very dramatically—in response to these upheavals. You might read elsewhere that objects created after these transformations are somehow less authentic because of the influence of European or Euro-American materials and subjects on Native art. However, it is crucial that we do not view those artworks as somehow less culturally valuable simply because Native men and women responded to new and sometimes radically changed circumstances.

Many twentieth and twenty-first century artists, including Oscar Howe (Yanktonai Sioux), Alex Janvier (Chipewyan [Dene]) and Robert Davidson (Haida), don’t consider themselves to work outside of so-called “traditional arts.” In 1958, Howe even wrote a famous letter commenting on his methods when his work was denounced by Philbrook Indian Art Annual Jurors as not being “authentic” Native art:

Who ever said that my paintings are not in the traditional Indian style has poor knowledge of Indian art indeed. There is much more to Indian Art than pretty, stylized pictures. There was also power and strength and individualism (emotional and intellectual insight) in the old Indian paintings. Every bit in my paintings is a true, studied fact of Indian paintings. Are we to be held back forever with one phase of Indian painting, with no right for individualism, dictated to as the Indian has always been, put on reservations and treated like a child, and only the White Man knows what is best for him? Now, even in Art, ‘You little child do what we think is best for you, nothing different.” Well, I am not going to stand for it. Indian Art can compete with any Art in the world, but not as a suppressed Art…. 1

More terms and issues

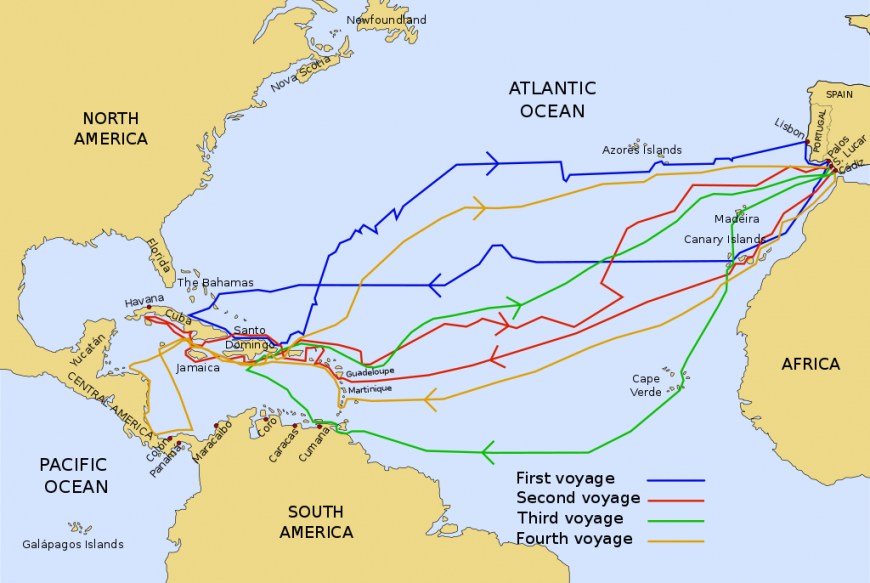

The word Indian is considered offensive to many peoples. The term derives from the Indies, and was coined after Christopher Columbus bumped into the Caribbean islands in 1492, believing, mistakenly, that he had found India. Other terms are equally problematic or generic. You might encounter many different terms to describe the peoples in North America, such as Native American, American Indian, Amerindian, Aboriginal, Native, Indigenous, First Nations, and First Peoples.

Native American is used here because people are most familiar with this term, yet we must be aware of the problems it raises. The term applies to peoples throughout the Americas, and the Native peoples of North America, from Panama to Alaska and northern Canada, are incredibly diverse. It is therefore important to represent individual cultures as much as we possibly can. The essays here use specific tribal and First Nations names so as not to homogenize or lump peoples together. On SmartHistory, the artworks listed under Native American Art are only those from the United States and Canada, while those in Mexico and Central America are located in other sections.

You might also encounter words like tribes, clans, or bands in relation to the social groups of different Native communities. The United States government refers to an Indigenous group as a “tribe,” while the Canadian government uses the term “ban.” Many communities in Canada prefer the term “nation.”

Identity

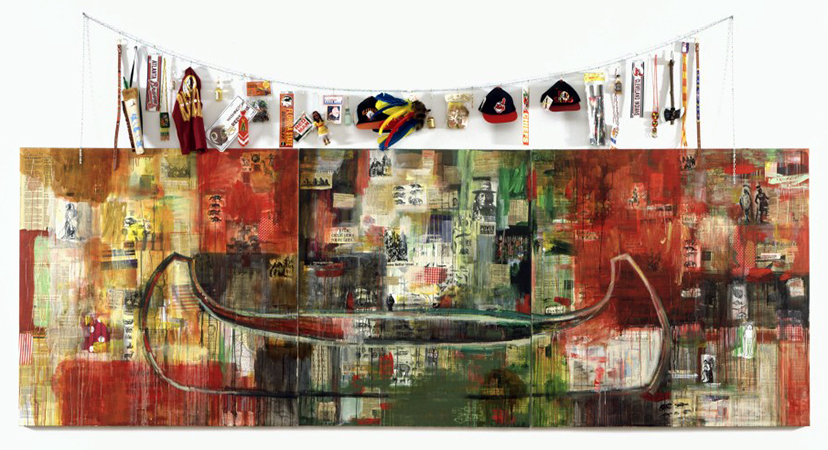

In order to be legally classified as an indigenous person in the United States and Canada, an individual must be officially listed as belonging to a specific tribe or band. This issue of identity is obviously a sensitive one, and serves as a reminder of the continuing impact of colonial policy. Many contemporary artists, including James Luna (Pooyukitchum/Luiseño) and Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith (from the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Indian Nation), address the problem of who gets to decide who or what an Indian is in their work.

Luna’s Artifact Piece (1987) and Take a Picture with a Real Indian (1993) both confront issues of identity and stereotypes of Native peoples. In Artifact Piece, Luna placed himself into a glass vitrine (like the ones we often see in museums) as if he were a static artifact, a relic of the past, accompanied by personal items like pictures of his family. In Take a Picture with a Real Indian, Luna asks his audience to come take a picture with him. He changes clothes three times. He wears a loincloth, then a loincloth with a feather and a bone breastplate, and then what we might call “street clothes.” Most people choose to take a picture with him in the former two, and so Luna draws attention to the problematic idea that somehow he is less authentically Native when dressed in jeans and a t-shirt.

Even the naming conventions applied to peoples need to be revisited. In the past, the Navajo term “Anasazi” was used to name the ancestors of modern-day Puebloans. Today, “Ancestral Puebloans” is considered more acceptable. Likewise, “Eskimo” designated peoples in the Arctic region, but this word has fallen out of favor because it homogenizes the First Nations in this area. In general, it is always preferable to use a tribe or Nation’s specific name when possible, and to do so in its own language.

Additional resources:

Interview with James Luna for the Smithsonian

The National Museum of the American Indian

Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips, Native North American Art, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

Brian M. Fagan, Ancient North America: The Archaeology of a Continent, 4th ed. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2005).

David W. Penney, North American Indian Art (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2004).

Karen Kramer Russell, ed., Shapeshifting: Transformations in Native American Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

About geography and chronological periods in Native American art

Typically when people discuss Native American art they are referring to peoples in what is today the United States and Canada. You might sometimes see this referred to as Native North American art, even though Mexico, the Caribbean, and those countries in Central America are typically not included. These areas are commonly included in the arts of Mesoamerica (or Middle America), even though these countries are technically part of North America.

So how do we consider so many groups and of such diverse natures? We tend to treat them geographically: Eastern Woodlands (sometime divided between North and Southeast), Southwest and West (or California), Plains and Great Basin, and Northwest Coast and North (Sub-Arctic and Arctic). While this is by no means a perfect way of addressing the varied tribes and First Nations within these areas, such a map can help to reveal patterns and similarities.

Chronology

Chronology (the arrangement of events into specific time periods in order of occurrence) is tricky when discussing Native American or First Nations art. Each geographic region is assigned different names to mark time, which can be confusing to anyone learning about the images, objects, and architecture of these areas for the first time. For instance, for the ancient Eastern Woodlands, you might read about the Late Archaic (c. 3000–1000 B.C.E.), Woodland (c. 1100 BCE–1000 C.E.), Mississippian (c. 900–c. 1500/1600 C.E.), and Fort Ancient (c. 1000–1700) periods. But if we turn to the Southwest, there are alternative terms like Basketmaker (c. 100 B.C.E.–700 C.E.) and Pueblo (700–1400 C.E.). You might also see terms like pre- and post-Contact (before and after contact with Europeans and Euro-Americans) and Reservation Era (late nineteenth century) that are used to separate different moments in time. Some of these terms speak to the colonial legacy of Native peoples because they separate time based on interactions with foreigners. Other terms like Prehistory have fallen out of favor and are problematic since they suggest that Native peoples didn’t have a history prior to European contact.

Organization

We arrange Native American and First Nations material prior to c. 1500 in a separate section which includes material about the Ancestral Puebloans, Moundbuilders, and Mississippian peoples. Those objects and buildings created after c. 1500 are in their own section, which will hopefully highlight the continuing diversity of Native groups as well as the transformations (sometimes violent ones) occurring throughout parts of North America. Artists working after 1914 (or the beginning of WWI) are located in both the Art of the Americas section, and in the modern and contemporary areas.

Additional resources:

Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips, Native North American Art, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

Brian M. Fagan, Ancient North America: The Archaeology of a Continent, 4th ed. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2005).

David W. Penney, North American Indian Art ( New York: Thames and Hudson, 2004).

Karen Kramer Russell, ed., Shapeshifting: Transformations in Native American Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

East

Global trade and an 18th-century Anishinaabe outfit

by DR. DAVID W. PENNEY, NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Anishinaabe outfit, c. 1790, collected by Lieutenant Andrew Foster, Fort Michilimackinac (British), Michigan, Birchbark, cotton, linen, wool, feathers, silk, silver brooches, porcupine quills, horsehair, hide, sinew; the moccasins were like made by the Huron–Wendat people (National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution), a Seeing America video

Speakers: Dr. David Penney, Associate Director for Museum Scholarship, Exhibitions, and Public Engagement, National Museum of the American Indian and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional resources

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

The bandolier bag

by DR. ADRIANA GRECI GREEN and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): A conversation with Dr. Adriana Greci Green and Dr. Steven Zucker. Shoulder Bag, 1840-1850, Delaware, Lenni Lenape, cotton, wool, silk, glass beads, tinned iron, brass, bone, 29 1/2 inches high (Newark Museum of Art, Purchase 2017 Mr. and Mrs. William V. Griffin Fund 2017.10)

Additional resources:

The Shoulder Bag at the Newark Museum of Art

Bandolier Bag

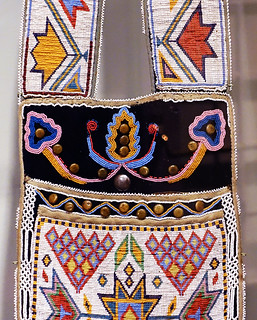

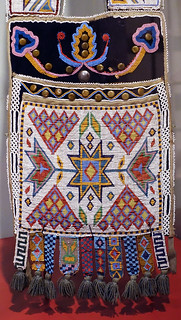

When looking at photographs of what we today call a Bandolier Bag (in the Ojibwe language they are called Aazhooningwa’on, or “worn across the shoulder”), it is nearly impossible to see the thousands of tiny beads strung together that decorate the bag’s surface.¹ This is an object that invites close looking to fully appreciate the process by which colorful beads animate the bag, making a dazzling object and showcasing remarkable technical skill.

What is a Bandolier Bag?

Bandolier Bags are based on bags carried by European soldiers armed with rifles, who used the bags to store ammunition cartridges. While Bandolier Bags were made by different tribes and First Nations across the Great Lakes and Prairie regions, they differ in appearance. The stylistic differences are the result of personal preference as much contact with Europeans and Euro-Americans, goods acquired in trade, and travel.

The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in New York City has a wonderful example of a Bandolier Bag, most likely made by a Lenape artist (the Lenape are part of the Delaware tribe or First Nation, who lived along the Delaware River and parts of what is today New York State).²

Bandolier Bags (like this one) are often large in size and decorated with a wide array of colorful beads and ribbons. They are worn as a cross-body bag, with a thick strap crossing a person’s chest to allow it to rest on the hip.

These bags were especially popular in the late nineteenth century in the Eastern or Woodlands region, which comprised parts of what is today Canada and the United States. The Woodlands area encompasses the Great Lakes Region and terrain east of the Mississippi River. This enormous geographic area has a long, complex history including the production of objects we today recognize as “art,” that date back more than 4,000 years.

Bandolier Bags were created across this vast expanse of land, and the NMAI has examples from the Upper Great Lakes region and Oklahoma. Due to events and laws like the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (signed by President Andrew Jackson), the Lenape were forcibly removed from these ancestral lands and relocated to areas of Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Ontario, Canada. Despite these traumatic relocations, tribes like the Lenape continued to create objects as they had in ancestral lands. Bandolier bags are one example of this continued artistic production.

Material and design

While men most commonly wore these bags, women created them. Initially, Bandolier Bags did not have a pocket, but were intended to complement men’s ceremonial outfits. Men even wore more than one bag on occasion, dressing themselves in a rainbow of colors and patterns. Even those bags with pockets weren’t necessarily always used to hold objects.

Women typically produced Bandolier Bags using trade cloth, made from cotton or wool. It is often possible to see the exposed unembroidered trade cloth underneath the cross-body strap. The NMAI bag (above) uses animal hide in addition to the cotton cloth, combining materials that had long been used among these groups (animal hides) with new materials (cotton trade cloth).

Beads and other materials were embroidered on the trade cloth and hide. The tiny glass beads, called seed beads, were acquired from European traders, and they were prized for their brilliant colors. Glass beads replaced porcupine quillwork, which had a longstanding history in this area. Before the use of glass beads, porcupine quills were acquired (carefully!), softened and dyed. Once they were malleable enough to bend, the quills were woven onto the surfaces of objects (especially clothing or other cloth goods like bags). Quillwork required different working techniques than embroidering with beads, so people adopted new methods for decorating the surfaces of bags, clothing, and other goods.

In addition to glass beads, the NMAI bag is decorated with silk ribbons—also procured via trade with Europeans. Much like the glass beads, silk ribbons offered a new material with a greater variety of color choices. Looking at the NMAI bag, we can see that the artists attached strips of yellow, blue, red, and green ribbons, like tassels, to the ends of the straps, as well as longer orange ribbons that fall below the bottom of the bag. Before the introduction of ribbons, women would paint the surface of hides in addition to decorating the bags with quillwork. Ribbons afforded women the opportunity to produce more textural variation, and to expand the surface of the bags in new ways. Imagine wearing this bag: the bright colors would attract attention and the sparkle of the beads would reflect sunlight as the ribbons fluttered in the wind or moved as one walked.

Further animating the surface of the NMAI Bandolier Bag is a red wool fringe, capped with metal cones that attach to the bag’s rectangular pouch. Like the ribbons and beads, the fringe and metal offered more colors and textures to the bag’s surface.

The designs on the bag are abstracted and symmetrical. White beads act as contour lines to help make the designs more visible to the naked eye. On the cross-body strap, we see a design that branches in four directions. Yet notice how the artist has actually made each side slightly different. The left portion of the strap displays a light blue background, and the repeating form is more rounded, with softer edges. On the right side of the strap, the blue is darker, the framing pink and green is varied, and the repeating form displays more straight lines. The small size of seed beads allowed for more curvilinear designs than quillwork.

It is possible that the contrasting colors represent the Celestial/Sky and Underworld realms. The abstracted designs on the sash may also be read in relation to the cosmos because they branch into four directions, which might relate to the four cardinal directions (north, south, east, and west) and the division of the terrestrial (earthly) realm into four quadrants.

Prairie Style

The NMAI Bandolier Bag relates to a broader array of objects that demonstrate the Prairie Style. The artist of the NMAI Bandolier Bag borrowed from older Delaware traditions, as well as those of other native peoples after they were forcibly relocated. Another Bandolier bag in the NMAI collection (below), by an Anishnaabe artist, demonstrates the “Prairie Style” clearly in the upper section where a floral motif floats against a dark ground.

The Prairie Style used colorful glass beads fashioned in floral patterns. The patterns could be either naturalistic flowers or abstract floral designs. A Sac and Fox breechcloth in the NMAI collection (left) is a clear example of the more abstract Prairie Style because the floral designs do not closely resemble flowers that you might see in nature (the Sacs or Sauks are an Eastern Woodlands group, the Fox tribe is closely related to them, and they are both centered in Oklahoma today, though there are Sac and Fox tribes in Iowa and Kansas as well).

The Prairie Style is the result of peoples coming into contact with one another, particularly in the wake of removal from their ancestral homelands. Floral forms, combined with the use of ribbons and colorful glass beads, not only attest to the transformations in artistic production, but also testifies to the creativity of people as they adapted to new situations. Bandolier Bags, as well as other objects and clothing, helped to express group identities and social status. In the wake of forced removals and threats to traditional ways of life, objects like the NMAI Bandolier Bag demonstrate the resilience and continued creativity of groups like the Lenape.

Today

Bandolier Bags are still made and worn today—attesting to their rich and complex history and their continuing ceremonial and cultural functions. For example, when the NMAI opened a new museum in Washington, D.C., in 2004, Ojibwe men wore colorful Bandolier Bags during the opening festivities and ceremonies. Artists continue to innovate by creating new interpretations of Bandolier Bags. Maria Hupfield, who belongs to the Wasauksing First Nation in Ontario, Canada, and currently lives in Brooklyn, made a Bandolier Bag from gray felt—an industrial material transformed into something beautiful and historically significant.

1. Anishnaabe is the name for the ethnic group that comprises the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi First Nations around the Great Lakes. Due to relocations of the nineteenth century, many other groups like the Delaware and Dakota currently live on the same lands.

2. In the United States, it is more common to see the term “Native American,” “Native,” or “Indigenous,” whereas “First Nations” used more frequently in Canada.

Additional resources:

Lenape Bandolier Bag in the National Museum of the American Indian

Sac and Fox man’s breechcloth in the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI)

Anishinaabe bandolier bag in the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI)

The NMAI blog on Maria Hupfield

David W. Penny, North American Indian Art, (London: Thames and Hudson, 2004).

Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips, Native North American Art, 2 ed. Oxford History of Art series (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

West

Juana Basilia Sitmelelene, Presentation Basket (Chumash)

by DR. LAUREN KILROY-EWBANK and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Juana Basilia Sitmelelene, Coin (Presentation) Basket, Chumash, Mission San Buenaventura, c. 1815-22, sumac, juncus textilis, mud dye, 9 x 48 cm (National Museum of the American Indian).Speakers: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Steven Zucker

Learn about this beautiful basket—a luxury item made by a Chumash woman in California (then, New Spain) at the time of the Mexican War of Independence from Spain—with motifs derived from Spanish coins.

War Shirt (Upper Missouri River)

by DR. JOHN P. LUKAVIC, DENVER ART MUSEUM

Studying art during a pandemic

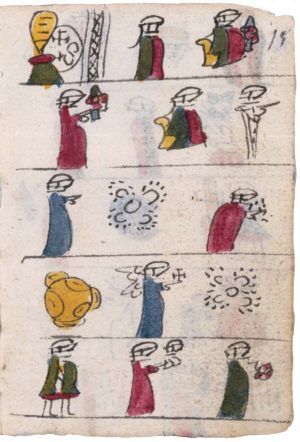

As many of us find ourselves working and studying from home while social distancing during the world-wide spread of COVID-19, let us think about the impact other pandemics and epidemics have had on world populations and their arts. Visual records open a window into such events, as we see in depictions of leprosy in European medieval illuminated manuscripts or in pictographic accounts of smallpox epidemics that spread across the Great Plains of North America in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[1] Northern plains groups experienced 36 epidemics between 1714 and 1919, which were documented in chronological order in winter counts.[2] A winter count depicted the most important events that occurred in any given year. Community elders would meet each year to discuss what had occurred since winter started (denoted by the first snowfall), and would select the most important event to name the year, after which a symbol (or pictograph) would be created and added to a hide painting.

One example is the 1837–38 smallpox epidemic which was catastrophic for the Mandan Nation.[3] According to historian Clay Jenkinson “In two waves of smallpox on the Upper Missouri, separated by 56 years, the Mandan had been reduced from a proud nation of more than 15,000 individuals to a pathetic remnant of 145.”[4] With so much loss we must consider the dramatic impact such events had on the transmission of Indigenous knowledge, but also celebrate these communities’ perseverance, and ability to adapt. Today the population of the Three Affiliated Tribes (Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara) have again risen to around 15,000 citizens who live on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota.[5]

Understanding this history of pandemic and loss provides us with a lens through which to see artworks from the upper Missouri River region. The scarcity of existing objects, and as a result, limited visual references create significant challenges in making specific attributions and comparisons from this region and period of time.

Still, some of the defining features of northern plains groups (at the time of contact) formed as a response to disease and the resulting loss of life. One scholar notes that “The social fluidity whereby tribes or divisions of tribes split apart and regrouped may have developed as a means of coping with catastrophic population loss.”[6] Epidemics affected all aspects of life for plains groups. For example, warriors could not train and military technology could not be developed if the group was sick and dying.[7]

Museum collections and the paintings of Catlin and Bodmer

We see evidence of the enormous population loss in men’s shirts from this time period. In this context, men’s shirts refer to a shirt worn by a warrior into battle or during festivals (so not daily use), and which are decorated with hair fringes (human and horse), ermine tails, quillwork, and beadwork. While we may know they were made by artists from this region, assigning an attribution to a particular community is difficult for several reasons. Few pre-1850 arts by Indigenous artists from any region exist in U.S. museums, although some can be found in international museums (including in the Paul Kane collection in the Manitoba Museum in Winnipeg and the collections of Prince Maximiliam of Wied in museums located in Berne, Berlin, and Stuttgart). Some collections exist from Lewis and Clark’s expedition from 1804–1806, but William Clark’s personal collection, once housed in his home in St. Louis until his death in 1838, went missing around this time and its whereabouts remains unknown to this day.[8] The total number of works of American Indian arts from the Plains before 1850 remains quite small.

When you narrow down these early nineteenth-century arts to shirts, and those exclusively from the upper Missouri River region, there are few examples with which to compare, and even fewer with documentation. Of the 40 shirts in the collection of the Denver Art Museum from the Plains and Plateau regions, only two date to around 1830 or before. One is attributed to an Assiniboine artist and the other is dated to 1800–20, and is the focus of this discussion.

With limited examples, great losses in the continuity of Indigenous knowledge, and works that predate photography by decades, the main way to identify these shirts is through the written reports of fur traders and explorers, as well as the paintings of George Catlin and Karl Bodmer who traveled in the region in the 1830s.

Interpreting what the shirt says about the man who wore it

In December of 2019 the Denver Art Museum received two shirts from the Upper Missouri region of the Plains as gifts from a private collector: one dating to around 1800–20 and the other to around 1855. The earlier of these two shirts is without question the single most significant work to come into DAM’s Native arts collection in decades.

It is exceedingly rare and among the earliest shirts from the Upper Missouri River region in existence. The shirt’s lack of beadwork, minimal use of Bayetta trade wool, and quilled design elements point to its early creation date and connection to this region.

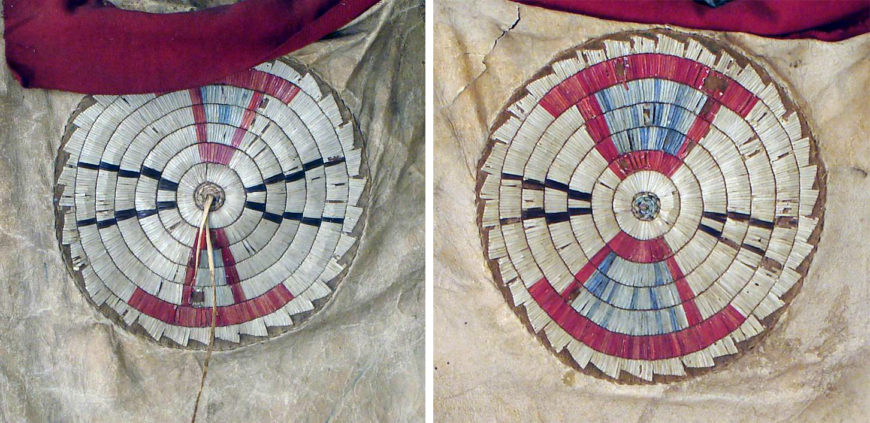

This fringed “poncho” style shirt with red trade wool rectangular “bibs” was made using Native tanned mountain sheep hides and sewn using sinew (animal tendons or ligaments used as thread). On both the front and back of the shirt are saw-tooth edged medallions (rosettes) and over each shoulder and along each sleeve are three quilled lanes with geometric patterning.

While little was recorded about the meanings of such elements, the medallions are commonly considered representations of forces of nature, such as the sun or powerful winds. It has also been suggested that the designs on medallions, such as those seen on this shirt and many others from this region, may represent the wings of a Thunderbird, a sacred being for many Plains tribes.

The central medallions are made from porcupine quills, likely plant material, and possibly also bird quills. Porcupine quillwork is a technique Indigenous to North America and was prevalent prior to the trade of European manufactured glass trade beads. Today this technique is experiencing a resurgence among many Native artists. The materials used on this shirt (as well as materials not used, such as glass beads) suggest it was made just as trade between fur trappers and Native people began in the central part of North America.

What is among the most exciting elements of this shirt are a series of pictographic and geometric drawings found on either side. If you look closely you will see faint indigo drawings of six heads, above which are floating lines. Below the heads is a row of four bear paws, and to the right are three pipes. The exact meaning of these elements was not recorded; however, based on Indigenous knowledge and with the help of Dr. Timothy McCleary, a colleague from Little Bighorn Tribal College at Crow Agency in Montana, we believe we know what they mean.

The heads with floating lines likely refer to counting coup, or striking an enemy with a stick. When a warrior touched his enemy with his coup stick, it was regarded as an act of extreme bravery because he had to get close to his opponent. The pipes may suggest how many times the shirt’s owner led successful war parties. The bear paws show how many Plains grizzlies the owner of the shirt had killed. Drawings and explanations in American ethnologist Garrick Mallery’s 1889 publication Picture Writing of the American Indians demonstrates how widespread such imagery was among Plains artists in the late nineteenth century. Mallery’s text reproduces a drawing and accompanying explanation by an Oglala Lakota man that explains the meaning of pipes depicted similarly to what we see in the shirt, as well as other design elements recorded on it.

The designs on the front of the shirt tell even more specific stories about the owner. Here, we find drawings of five X-like forms arranged below the medallion. These are war honor marks. From left to right, we can read these to recount the original owner’s achievements in war. The first shows that the warrior was the third person to touch a live enemy in battle (counting coup). The next shows that after he had dismounted an enemy, the owner of the shirt captured the enemy’s horse. The next two Xs show he was the fourth person to count coup on an enemy during battle. Then the last shows that he was again the third to count coup on an enemy. Mallery recorded variations of these designs and meanings as told to him by Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara consultants.

These marks were common ways to record war deeds among the Native people of the Upper Missouri River region and are found on clothing, tipis, and in rock art. The Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, and Crow people are well known for their use of this X to represent an enemy. While a few other tribes also used this imagery, this form with the associated hash marks (denoting the number of coups) and horse hoof prints are all from one of the Upper Missouri River tribes.

Ongoing challenges

Indigenous people have faced countless challenges to their ways of life since the arrival of settler-colonial people. Sickness and disease took its toll, but so did forced relocation, land allotment that broke up clan and society structures, prohibitions against ceremonies and religions, traumatic boarding school experiences, broken treaties, and institutional and structural racism, to name a few. Each of these created seemingly insurmountable hurdles for Indigenous people to overcome.

Many of these challenges still exist. The Navajo Nation has been hit hard by COVID-19. Two Lakota reservations are under attack from the governor of South Dakota for the medical checkpoints they put up on their own roads to protect their citizens from the spread of this disease. Generational trauma from past experiences warns them to protect themselves. Elders are the keepers of knowledge and they are most at risk. The transmission of intergenerational knowledge of all forms, visual arts included, is difficult during such times. But this knowledge still exists in communities. These art forms are still being created by brilliant and innovative Indigenous youth. And this should give us hope for the future.

Notes:

[1] Linea Sundstrom, “Smallpox Used Them up: References to Epidemic Disease in Northern Plains Winter Counts, 1714–1920,” Ethnohistory 44, no. 2 (Spring, 1997), pp. 305–343

[2] Sundstrom, “Smallpox Used Them up,” p. 308

[3] It has been suggested that the Mandans, Arikaras, and Hidatsas from the upper Missouri River region lost a combined 70% of their populations. Donald J. Lehmer, “Epidemics among the Indians of the Upper Missouri,” in Selected Writings of Donald J. Lehmer, ed. W. Raymond Wood, Reprints in Anthropology no. 8 (I977), pp. 105–11

[4] Clay Jenkinson, “Smallpox and Indians: When Pandemic Warnings Go Unheeded,” in Governing, April 22, 2020, https://www.governing.com/context/Smallpox-and-Indians-When-Pandemic-Warnings-Go-Unheeded.html

[5] Jenkinson, “Smallpox and Indians”

[6] Sundstrom, “Smallpox Used Them up,” p. 325

[7] Sundstrom, “Smallpox Used Them up,” p. 325.

[8] Norman Feder, American Indian Art Before 1850, Denver Art Museum Summer Quarterly (1965), p. 5; National Park Service, Department of the Interior, “William Clark’s Indian Museum: A Tradition Continued,” in The Museum Gazette (October 1997), p. 5

Additional resources

Learn more about the Denver Art Museum’s collection of Indigenous Arts of North America

Learn about Lakota Winter Counts in this Smithsonian video

Learn more about narrative art of the Plains from the National Museum of the American Indian

Colin Taylor, “Analysis and Classification of the Plains Indian Ceremonial Shirt: John C. Ewers Influence on a Plains Material Culture Project,” in Fifth Annual Plains Indian Seminar in Honor of Dr. John C. Ewers, ed. George P. Horse Capture and Gene Ball (Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, 1980)

David W. Penney, Art of the American Frontier: The Chandler-Pohrt Collection (Detroit Institute of Arts, 1992)

George Horse Capture and Joseph D. Horse Capture, Beauty, Honor and Tradition: The Legacy of Plains Indian Shirts (University of Minnesota Press, 2001)

Colin F. Taylor, Buckskin & Buffalo: The Artistry of the Plains Indians (New York: Rizzoli, 1998)

George Catlin and His Indian Gallery (Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2002)

David C. Hunt and Marsha V. Gallagher, Karl Bodmer’s America (Joslyn Art Museum, 1984)

Emma I. Hansen, Memory and Vision: Arts, Cultures and Lives of Plains Indian Peoples (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2007)

Garrick Mallery, Picture Writing of the American Indians, Volume I (New York: Dover Publications, 1972). A reprint of the paper “Picture Writing of the American Indians,” in the Tenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1888-89, by J. W. Powell, Director, published by the Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. in 1893

Norman Feder, “Plains Pictographic Painting and Quilled Rosettes,” in American Indian Art Magazine, Vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 54–62

Colin F. Taylor, Saam: The Symbolic Content of Early Northern Plains Ceremonial Regalia, (Verlag Fur Amerikanistik, 1993)

Norman Feder, Two Hundred Years of North American Indian Art (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1971)

John F. Taylor , I977, “Sociocultural Effects of Epidemics on the Northern Plains: 1734–1850,” Western Canadian Journal of Anthropology 7 (4): pp. 55–81

Bear Claw Necklace (Pawnee)

by DR. JOHN P. LUKAVIC, DENVER ART MUSEUM and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Bear Claw Necklace (Pawnee), before 1870, grizzly bear claws and hide, otter pelt, beads, cedar, tobacco and other materials (Denver Art Museum), a SmartHistory Seeing America video

Speakers: Dr. John Lukavic, curator of Native Arts, Denver Art Museum and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional historical narratives:

Matt Reed

Tribal Historic Preservation Officer, Cultural Resource Division of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma notes that:

When the Lakota attacked, Sky Chief put the necklace and the family’s sacred bundle on his young daughter, put her on his horse, and told her to run. She made it to safety. Sky Chief died right after he killed his own little boy to prevent the child’s capture, torture, and death by the Sioux. When Sky Chief’s daughter eventually got back to Genoa, Nebraska (then the Pawnee Reservation), the little girl, now an orphan, was taken in by Bluehawk (Matt Reed’s grandfather), who raised her as his own. She grew up, married, and in 1987, her granddaughter, Elizabeth, gave the sacred bundle to the Earthlodge Museum in Republic, Kansas. More information on the bundle can be found here.

Roger Echo-Hawk

Pawnee tribal historian, notes that:

Stacy Matlock, a Chaui Pawnee chief, was said to have worn this necklace in 1925 during a visit to the Lakota when they formally apologized for the 1873 attack at Massacre Canyon. The Denver Art Museum acquired the necklace in 1973.

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Eastern Shoshone: Hide Painting of the Sun Dance, attributed to Cotsiogo (Cadzi Cody)

Animal hide painting

Painting on animal hides is a longstanding tradition of the Great Basin and Great Plains people of the United States, including the Kiowa, Lakota, Shoshone, Blackfeet, Crow, Dakota, and Osage. While the earliest surviving hide paintings date to around 1800, this tradition was undoubtedly practiced much earlier along with other forms of painting like petroglyphs (rock engravings).

Painting, in tandem with oral traditions, functioned to record history. Often artists like Cotsiogo (Eastern Shoshone; pronounced “co SEE ko”), who is also known by his Euro-American name, Cadzi Cody, painted on elk, deer, or buffalo hides using natural pigments like red ochre and chalk, and eventually paints and dyes obtained through trade. Usually, artists decorated the hides with geometric or figural motifs. By the later nineteenth century certain hide artists like Cotsiogo began depicting subject matter that “affirmed native identity” and appealed to tourists. The imagery placed on the hide was likely done with a combination of free-hand painting and stenciling.

Men and women both painted on hides, but men usually produced the scenes on tipis (tepees), clothing, and shields. Many of these scenes celebrated battles and other biographical details. The Brooklyn Museum’s hide painting by Cotsiogo may have functioned as a wall hanging and has also been classified as a robe.

The artist

Cotsiogo (also Codsiogo, Katsikodi or Cadzi Cody), a member of the Eastern Shoshone tribe, painted many hides in addition to the two shown above. They represent his experiences during a period of immense change for the Shoshone people. During his lifetime, Cotsiogo was placed on the Wind River Reservation in central western Wyoming.

The Wind River Reservation is the size of Rhode Island and Delaware combined and had been established by the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868. Prior to their placement on the Wind River Reservation, the Shoshone moved with the seasons and the availability of natural resources. Many Shoshone traversed the geographic regions we now call the Great Plains and Plateau regions.

Cotsiogo likely created the Brooklyn Museum hide painting (above) for Euro-American tourists who visited the reservation. It might explain why there is a scene of buffalo hunting, a scene which was thought to be desirable to tourists. Its production helped to support him after the Shoshone were moved to the reservation. With newly established trade markets and the influx of new materials, artists like Cotsiogo sometimes produced work that helped support themselves and their families.

Subject matter

Cotsiogo’s Brooklyn Museum hide painting combines history with the contemporary moment. It displays elements of several different dances, including the important and sacred Sun Dance and non-religious Wolf Dance (tdsayuge or tásayùge). The Sun Dance surrounds a not-yet-raised buffalo head between two poles (or a split tree), with an eagle above it. Men dressed in feather bustles and headdresses—not to be confused with feathered war bonnets—dance around the poles, which represents the Grass Dance. With their arms akimbo and their bodies bent, Cotsiogo shows these men in motion. Men participating in this sacred, social ceremony refrained from eating or drinking.

The Sun Dance was intended to honor the Creator Deity for the earth’s bounty and to ensure this bounty continued. It was a sacred ceremony that tourists and anthropologists often witnessed. However, the United States government deemed it unacceptable and forbid it. The U.S. government outlawed the Sun Dance until 1935, in an effort to compel Native Americans to abandon their traditional ways. Cotsiogo likely included references to the Sun Dance because he knew tourist consumers would find the scene attractive; but he modified the scene combining it with the acceptable Wolf Dance, perhaps to avoid potential ramifications. The Wolf Dance eventually transformed into the Grass Dance which is performed today during pow wows (ceremonial gatherings).

The hide painting also shows activities of daily life. Surrounding the Sun Dance, women rest near a fire and more men on horses hunt buffaloes. Warriors on horses are also shown returning to camp, which was celebrated with the Wolf Dance. Two tipis represent the camp, with the warriors appearing between them. Some of the warriors wear feathered war bonnets made of eagle feathers. These headdresses communicated a warrior acted bravely in battle, and so they functioned as symbols of honor and power. Not just anyone could wear a feathered war bonnet!

Cotsiogo shows the warriors hunting with bows and arrows while riding, but in reality Shoshone men had used rifles for some time. Horses were introduced to the Southwest by Spaniards. Horses made their way to some Plains nations through trade with others like the Ute, Navajo, and Apache. By the mid-eighteenth century, horses had become an important part of Plains culture.

Buffaloes were sacred to the Plains people because the animals were essential to their livelihood. Some scenes display individuals skinning buffaloes and separating the animals’ body parts into piles. All parts of the buffalo were used, as it was considered a way of honoring this sacred animal. At the time Cotsiogo painted this hide, most buffalo had either been killed or displaced. Buffaloes had largely disappeared from this area by the 1880s. Cotsiogo’s hide thus marks past events and deeds rather than events occurring at the time it was created.

Editor’s note on the contemporary situation on the Wind River Reservation :

According to The New York Times, the 14,000 current residents of the Wind River Reservation suffer a crime rate more than five times the national average, a life expectancy of only 49 years, and an unemployment rate that may be above 80 percent.

Additional resources:

Information on Cotsiogo, University of Wyoming

Hide with history of Eastern Shoshone Chief Washakie’s combats

A Song of the Horse Nation: Horses in Native American Cultures, an exhibit at the NMAI

Feathered war bonnet

More than an accessory (way more)

Today it might be fairly common to see feathered headdresses worn at outdoor music festivals as an attractive or visually powerful accessory. However, feathered headdress replicas in this context misuse important cultural and spiritual objects of the Native tribes of the Great Plains. These objects have become so popular in our contemporary cultural imagination (like in many Western movies) that we often assume that the feathered headdress was a prevalent item of Plains dress (and all First Nations and indigenous groups)—especially as they were envisioned by nineteenth-century Euro-American artists such as Karl Bodmer or George Catlin.

Catlin’s Máh-to-tóh-pa (”Four Bears,” painted 1832), for instance, shows the Mandan chief standing in a war shirt with leggings and festooned with a feathered headdress that frames his head and extends down the length of his back.¹ Works like this one were often sent around North America to introduce unfamiliar people to Native peoples of the Great Plains, causing many to assume that such headdresses were commonplace items.

However, feathered headdresses, or more correctly, eagle-feather war bonnets, were and are objects of great significance for peoples of the Plains tribes. As described in a White River Sioux story about Chief Roman Nose, “He had the fierce, proud face of a hawk, and his deeds were legendary. He always rode into battle with a long warbonnet trailing behind him. It was thick with eagle feathers, and each stood for a brave deed, a coup counted on the enemy.”¹

A male warrior had to earn the privilege of wearing a war bonnet, like the Cheyenne or Sioux war bonnet in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection (left). This item of adornment, along with the warrior’s clothing, communicated his rank in a given warrior society. Someone could not just decide to wear one–it was decidedly not a fashion accessory. In fact, to acquire a war bonnet a warrior had to display great bravery in battle. On those occasions that a warrior accomplished great deeds or battle coups, he received an eagle feather. For this reason, feathers also recalled specific moments in time. When worn into battle, a warrior could not surrender his war bonnet, and so it acquired associations with bravery and valiancy. Warriors who had elaborate bonnets clearly possessed these desirable qualities in great quantities.

Only important chiefs and warriors could don a war bonnet, and they were typically worn during ceremonies; certain types of war bonnets would have been difficult to wear into battle, especially those that trailed down the length of the back. Regardless of when they were worn, imagine a warrior on horseback wearing a war bonnet: he would seem to be moving, as if he were a bird in flight—a striking and intimidating appearance. War bonnet feathers could take several different forms, they might stand straight-up, create a halo around the face, or trail down the back.

From the front, the Brooklyn Museum’s war bonnet fanned outwards and framed an individual’s head, almost like the rays of the sun. Eagle feathers—actually the tail feathers of golden eagles—rise upwards and outwards from a hide band decorated with colored glass beads. The beads, common on many mid-to late nineteenth-century war bonnets, were acquired from European and Euro-American traders, often replacing quillwork decoration (decorative element made with porcupine quills). Colorful and easy to manipulate, glass beads were used to create intricate decorative patterns on a variety of objects, including clothes. The Brooklyn Museum’s war bonnet shows a stepped-fret pattern that alternates between red and blue, with all the forms picked out by a thick contour line. These bead colors paired with the white and grey eagle feathers, yellow-dyed horse hair, and tiny red-pink downy tufts create a beautiful, colorful object, one that is also remarkable for the different textures presented to the eye. The materials of this object betray its date of creation in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. Earlier war bonnets did not have the pink fluff, but would have had only horsehair at the tips.

This particular war bonnet was clearly for someone of great importance. This is evident because of the numerous feathers in the bonnet itself and because of the feathers that run down the length of the body. Women did not traditionally wear war bonnets, although occasionally after battle, when their male family members—say their husbands—returned, they might don the war bonnet while dancing to celebrate.

Warrior dress

It is important not to think of the feathered war bonnet alone or as the only dress item that demonstrated a warrior’s status and accomplishments. A warrior would also be wearing a war shirt, breastplate, and leggings to complete his outfit. Similar to the way in which a feather was earned for brave deeds, the stripes on a warrior’s leggings could designate specific exploits. War shirts also communicated a warrior’s status because locks of hair (horse or human) could be attached to a shirt to showcase accomplishments such as combat or capturing horses. Designs on war shirts, too, could note such accomplishments.

Tipi liners

Besides dress, other objects related triumphs in battle including narrative tipi liners (hides used to decorate the interior of a tipi, also teepee) or buffalo-hide robes. While the tipi itself would be fashioned by women, tipi liners with narrative scenes were created by men. These autobiographical and historical narrative scenes often depicted battle scenes that commemorated brave deeds in battle.

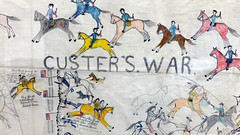

A muslin tipi liner in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection (above, and detail below), created during the early Reservation period (1880–1920) shows the battle exploits of the Lakota warrior Rain-In The-Face (Ité Omágaˇzu, who lived on the Standing Rock reservation in North Dakota) at a time when life for many people living on the Great Plains had been violently disrupted by Euro-American soldiers. Native peoples had been forcibly removed from their homes and lands and placed on reservations, and so their previous ways of life were in a moment of crisis and transition. As a result, prior deeds and acts of battle coups became important to remember as a source of cultural, historical, and ceremonial pride. Rain-In-The-Face’s tipi liner draws on earlier traditions commemorating a warrior’s battle exploits—in this case his own—but does so in a new medium (muslin, crayon and pencil rather than painted hide) and in a new context—living on the reservation. In some scenes on the liner, Rain-In-The-Face is shown on horseback, holding weapons and a shield and riding in battle.

Today people do not earn war bonnets from great battle accomplishments, but by helping a given community in some way. A war bonnet might also commemorate one’s deeds in the U.S. military, a different way to remember one’s strength and courage (versus the battles of the nineteenth century and earlier).

The war bonnet in popular culture

While the feathered headdress is common at many outdoor music festivals and makes a regular appearance in many popular culture films, images, and objects, there have been sustained attempts by many Native groups to end this appropriation for the problematic stereotypes and misunderstanding it conveys. In particular, the misconception that all Native American peoples wore and still wear feathered headdresses, rather than the male warriors and chiefs of the Great Plains who earned the right to wear them. The war bonnet as a contemporary fashion accessory perpetuates a lack of understanding of the postcolonial fate of Native groups across North America.

1. “Chief Roman Nose Loses His Medicine,” in American Indian Myths and Legends, edited by Richard Erdoes and Alfonso Ortiz (New York: Pantheon Books, 1984), 256.

Additional resources:

The war bonnet in the Brooklyn Museum

The White Cloud, Head Chief of the Iowas (for more on George Catlin)

The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky

Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Plains Indian Museum

Blog post from Native Appropriations, “But Why Can’t I Wear a Hipster Headdress?”

Max Carocci, Ritual and Honour: Warriors of the North American Plains (London: British Museum Press, 2011).

Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips, Native North American Art, 2 ed. Oxford History of Art series (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

David W. Penny, North American Indian Art, (London: Thames and Hudson, 2004).

Nancy Rosoff and Susan Kennedy Zeller, eds. Tipi: Heritage of the Great Plains (University of Washington Press, 2010).

Gaylord Torrence, The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky (Skira, 2014).

Nellie Two Bear Gates, Suitcase

by DR. JILL AHLBERG YOHE, MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ART and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Nellie Two Bear Gates, Suitcase, 1880-1910, beads, hide, metal, oilcloth, thread (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Additional resources:

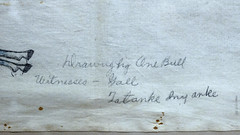

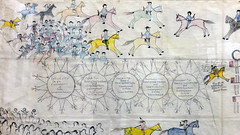

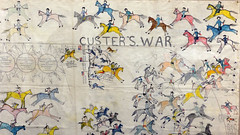

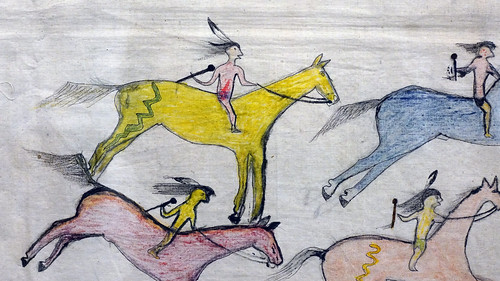

Henry Oscar One Bull, Custer’s War

by DR. JILL AHLBERG YOHE, MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ART and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Henry Oscar One Bull/Tȟatȟáŋka Waŋžíla (Hunkpapa Lakota), Custer’s War, c. 1900, 39 x 69 inches (irregular), pigments, ink on muslin (Minneapolis Institute of Art)

Additional resources:

Statements by Henry Oscar One Bull, University of Oklahoma Library

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Southwest

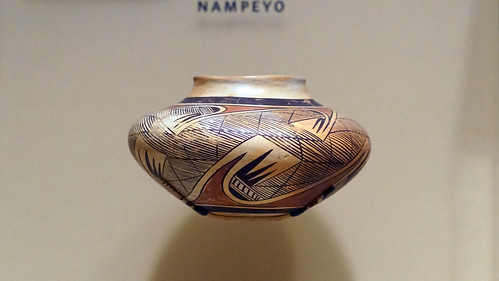

Nampeyo (Hopi-Tewa), polychrome jar

by DR. DAVID W. PENNEY, NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Nampeyo (Hopi-Tewa), polychrome jar, c. 1930s, clay and pigment, 13 x 21 cm (National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution), a Seeing America video

Speakers: Dr. David Penney, Associate Director for Museum Scholarship, Exhibitions, and Public Engagement, National Museum of the American Indian and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional resources

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

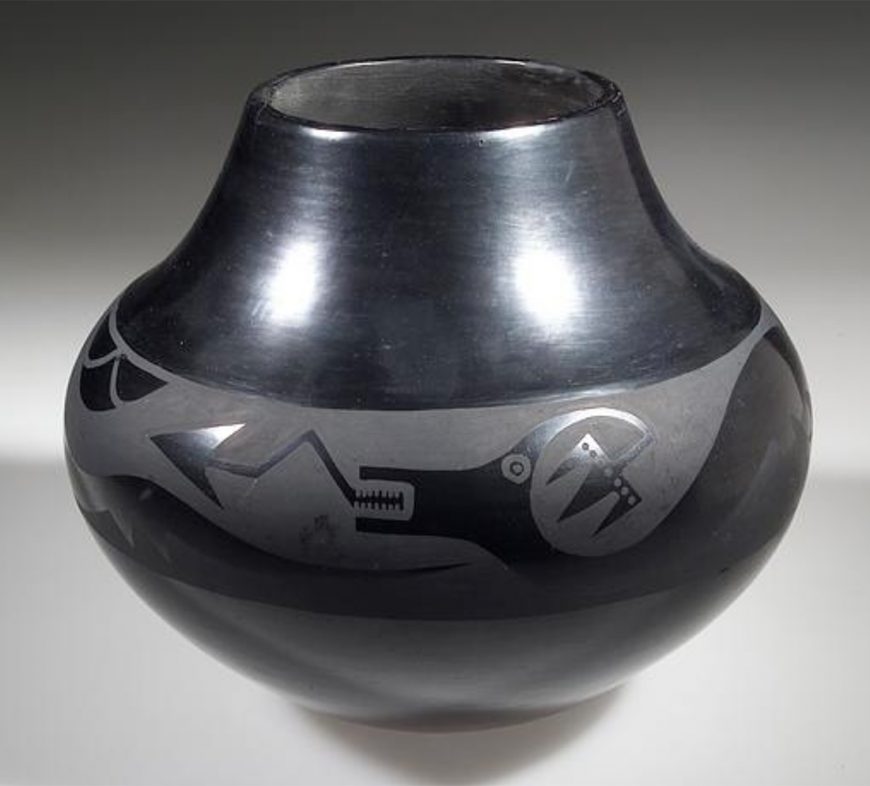

Puebloan: Maria Martinez, Black-on-black ceramic vessel

Born Maria Antonia Montoya, Maria Martinez became one of the best-known Native potters of the twentieth century due to her excellence as a ceramist and her connections with a larger, predominantly non-Native audience. Though she lived at the Pueblo of San Ildefonso, about 20 miles north of Santa Fe, New Mexico, from her birth in 1887 until her death in 1980, her work and her life had a wide reaching importance to the Native art world by reframing Native ceramics as a fine art. Before the arrival of the railroad to the area in the 1880s, pots were used in the Pueblos for food storage, cooking, and ceremonies. But with inexpensive pots appearing along the rail line, these practices were in decline. By the 1910s, Ms. Martinez found a way to continue the art by selling her pots to a non-Native audience where they were purchased as something beautiful to look at rather than as utilitarian objects.

Her mastery as a ceramist was noted in her village while she was still young. She learned the ceramic techniques that were used in the Southwest for several millennia by watching potters from San Ildefonso, especially her aunt Nicholasa as well as potters (including Margaret Tafoya from Santa Clara), from other nearby Pueblos. All the raw materials had to be gathered and processed carefully or the final vessel would not fire properly. The clay was found locally. To make the pottery stronger it had to be mixed with a temper made from sherds of broken pots that had been pounded into a powder or volcanic ash. When mixed with water, the elasticity of the clay and the strength of the temper could be formed into different shapes, including a rounded pot (known as an olla) or a flat plate, using only the artist’s hands as the potting wheel was not used. The dried vessel needed to be scraped, sanded, smoothed, then covered with a slip (a thin solution of clay and water). The slip was polished by rubbing a smooth stone over the surface to flatten the clay and create a shiny finish—a difficult and time-consuming process. Over the polished slip the pot was covered with designs painted with an iron-rich solution using either pulverized iron ore or a reduction of wild plants called guaco. These would be dried but required a high temperature firing to change the brittle clay to hard ceramics. Even without kilns, the ceramists were able to create a fire hot enough to transform the pot by using manure.

Making ceramics in the Pueblo was considered a communal activity, where different steps in the process were often shared. The potters helped each other with the arduous tasks such as mixing the paints and polishing the slip. Ms. Martinez would form the perfectly symmetrical vessels by hand and leave the decorating to others. Throughout her career, she worked with different family members, including her husband Julian, her son Adam and his wife Santana, and her son Popovi Da. As the pots moved into a fine art market, Ms. Martinez was encouraged to sign her name on the bottom of her pots. Though this denied the communal nature of the art, she began to do so as it resulted in more money per pot. To help other potters in the Pueblo, Ms. Martinez was known to have signed the pots of others, lending her name to help the community. Helping her Pueblo was of paramount importance to Ms. Martinez. She lived as a proper Pueblo woman, avoiding self-aggrandizement and insisting to scholars that she was just a wife and mother even as her reputation in the outside world increased.

Maria and Julian Martinez pioneered a style of applying a matte-black design over polished-black. Similar to the pot pictured here, the design was based on pottery sherds found on an Ancestral Pueblo dig site dating to the twelfth to seventeenth centuries at what is now known as Bandelier National Monument. The Martinezes worked at the site, with Julian helping the archaeologists at the dig and Maria helping at the campsite. Julian Martinez spent time drawing and painting the designs found on the walls and on the sherds of pottery into his notebooks, designs he later recreated on pots. In the 1910s, Maria and Julian worked together to recreate the black-on-black ware they found at the dig, experimenting with clay from different areas and using different firing techniques. Taking a cue from Santa Clara pots, they discovered that smothering the fire with powdered manure removed the oxygen while retaining the heat and resulted in a pot that was blackened. This resulted in a pot that was less hard and not entirely watertight, which worked for the new market that prized decorative use over utilitarian value. The areas that were burnished had a shiny black surface and the areas painted with guaco were matte designs based on natural phenomena, such as rain clouds, bird feathers, rows of planted corn, and the flow of rivers.

The olla pictured above features two design bands, one across the widest part of the pot and the other around the neck. The elements inside are abstract but suggest a bird in flight with rain clouds above, perhaps a prayer for rain that could be flown up to the sky. These designs are exaggerated due to the low rounded shapes of the pot, which are bulbous around the shoulder then narrow at the top. The shape, color, and designs fit the contemporary Art Deco movement, which was popular between the two World Wars and emphasized bold, geometric forms and colors. With its dramatic shape and the high polish of surface, this pot exemplifies Maria Martinez’s skill in transforming a utilitarian object into a fine art.

The work of Maria Martinez marks an important point in the long history of Pueblo pottery. Ceramics from the Southwest trace a connection from the Ancestral Pueblo to the modern Pueblo eras. Given the absence of written records, tracing the changes in the shapes, materials, and designs on the long-lasting sherds found across the area allow scholars to see connections and innovations. Maria Martinez brought the distinctive Pueblo style into a wider context, allowing Native and non-Native audiences to appreciate the art form.

Additional resources:

This pot at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

The Art, Life and Legacy of Maria Martinez

Maria Martinez Pottery – San Ildefonso Pueblo

Maria Martinez (Through the Eyes of the Pot: A study of Southwest Pueblo Pottery and Culture)

Maria Martinez: Indian Pottery of San Ildefonso (documentary video, 1972)

R. L. Bunzel, The Pueblo Potter: A Study of Creative Imagination in Primitive Art (Dover Publications, 1929).

Hazel Hyde, Maria Making Pottery: The Story of Famous American Indian Potter Maria Martinez (Sunstone Press, 1992).

Alice Marriott, Maria: The Potter of San Ildefonso (University of Oklahoma Press, 1987).

Susan Peterson and Francis H. Harlow, The Living Tradition of Maria Martinez (Kodansha, 1992).

—–, Pottery by American Indian Women: The Legacy of Generations (Abbeville Press, 1997).

Richard Spivey,The Legacy of Maria Poveka Martinez (Museum of New Mexico Press, 2003).

Stephen Trimble, Talking with the Clay: The Art of Pueblo Pottery in the 21st Century (School of American Research Press, 2007).

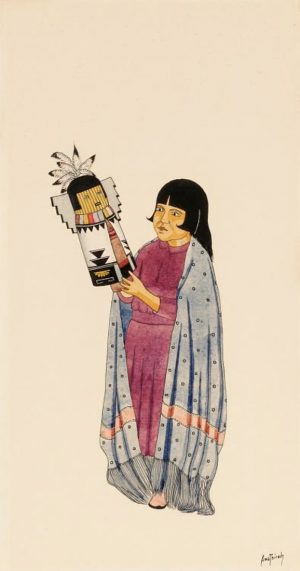

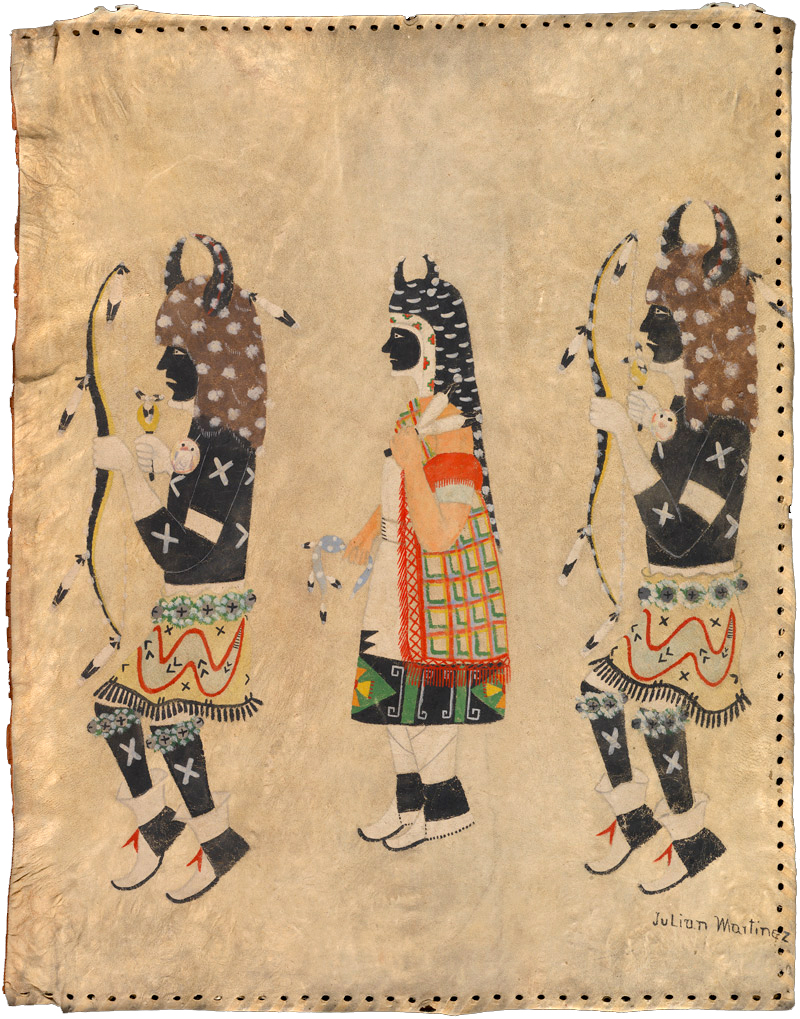

Julian Martinez, Buffalo Dancers

Famous Pueblo pottery

As an artist, Julian Martínez from San Ildefonso Pueblo is best known for the ceramics he made with his wife, Maria Martínez. Together, they produced the matte-black on polished-black pottery for which they and their Pueblo colleagues gained international fame.

Maria formed the pots into elegant shapes and Julian painted the designs, both geometric and figurative, including historic motifs such as the feather pattern from Mimbres pottery and the avanyu, the horned serpent similar the Mesoamerican deity Quetzalcoatl.

Julian Martínez also worked at the Museum of New Mexico, where he took advantage of the opportunity to study the Museum’s collection of Southwestern pottery, and he learned more during the summers when he worked at the field school at the Pajarito Plateau (later renamed Bandelier National Monument). In addition to his work on pottery, Martínez drew on paper; he always kept a notebook where he sketched ideas and recorded what he had seen. Though most of his images were painted on paper, he created a few murals on walls and, on rare occasions, he painted on hide, as he did for his Buffalo Dancers from about 1930, now in the collection of the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City (below).

Pueblo painting

Painting has long been part of Pueblo life; it can be found on the walls of the kivas (the round ceremonial structures usually partially underground) and on dance regalia such as wands, tablitas (ceremonial headdresses), clothing, and other items. A thriving art community developed around 1900 during a difficult time in Pueblo history: due to illness and outward migration, the population was reduced to less than 200. When the Atchison Topeka and Santa Fe Railway extended its track to the area in 1880, the economy of the Pueblo was transformed as more outside goods were purchased and more items, especially ceramics and paintings on paper, were made to sell to tourists traveling to the area.

An important group of Pueblo artists called the San Ildefonso Self-Taught Group, active from around 1900 to around 1930, included Julian Martínez, Tonita Peña, Crescencio Martínez, and Awa Tsireh (Alfonso Roybal). Most of their work depicted scenes common to Pueblo life, mainly ceremonial dances and genre scenes.

The Buffalo Dance

Martínez was elected governor of San Ildefonso in 1925 and he served as a leader in ceremonies. Like other Pueblo painters, he refrained from depicting ritual objects, sites, and altars that were considered private, and focused instead on dances that were open to the public. The Buffalo Dance is one of the most commonly represented of all Pueblo dances by the Self-Taught Group. Art historian J.J. Brody described it as one of the most “comprehensible to outsiders of all public ritual dances of the Pueblo people.” [1] Performed annually on January 23rd to honor the Pueblo patron saint, San Ildefonso, the Buffalo Dance enacts a hunting scene, with three dancers playing the roles of a hunter, buffalo, and a buffalo maiden (or buffalo mother) who has the power to induce the animals to sacrifice themselves to provide food and hide.

Early twentieth-century Pueblo paintings by artists including Tsireh, Peña, and Martínez all depict the Buffalo Dance in the same way, with the three figures in profile, facing the same direction as they would be during the dance. The men wear a buffalo headdress and dance kilts with depictions of avanyu (a horned serpent), and their skin is painted black. The buffalo maiden wears an embroidered one-shouldered manta, or dress.

In this hide painting, Martínez gave all three figures the same facial features, focusing instead on varying details in their clothing and regalia. There is no sense of space; the figures lack modeling and do not cast shadows. The flatness of the figures and the lack of a background suggest the influence of early Modernist abstraction. The empty space might also symbolize an area that is sacred—unbound by place or time. Paintings of such dances might even portray a space where the viewers themselves also participate in the dance, because, as anthropologist Alfonso Ortiz from Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo has observed, everyone in the community dances in ceremonies.[2]

Though Martínez painted several versions of the Buffalo Dance, the NMAI version is unusual for its material: animal hide. More commonly used in art from the Plains, hide is stronger and suppler than paper as a base. This particular hide has small holes on along three of its sides, suggesting that it was used to cover a portfolio or large book, with a string or leather cord run through the holes to attach it over a group of drawings.[3] Later, the image may have been unlaced and cut along one side, accounting for the smooth edge.

Pueblo painting continues

With its bright colors and strong forms, Julian Martínez’s Buffalo Dancers exemplifies the early period of Pueblo painting. In 1932, the Santa Fe Indian School (whose painting program became known as “The Studio School”) started teaching art, and developed the Santa Fe Indian School Style. This new style retained the earlier emphasis on dance and genre scenes with the same flatness and lack of modeling, but the work became more decorative and lost the intimacy of the earlier works.

During Martínez’s his life, local artists, anthropologists, and ethnographers expressed their appreciation for his work, noting his radiant colors, technical skill, and mastery of form. Martínez’s Buffalo Dancers, like other paintings produced by the San Ildefonso Self-Taught Group, conveys a sense of movement and energy in its figures and shares the joy of the ceremonies.

[1] J.J. Brody, Pueblo Indian Painting: Tradition and Modernism in New Mexico (School for Advanced Research Press, 1997).

[2] Alfonzo Ortiz, The Tewa World: Space, Time, Being and Becoming in a Pueblo Society (Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, 1969).

[3] I am indebted to Dr. Jonathon Batkin and Dr. Bruce Bernstein for sharing this idea.

Additional resources:

This work in the Infinity of Nations exhibition at the National Museum of the American Indian

Claremont Colleges Digital Library, “Pueblo and Plains Indian Watercolors.”

Mimbres Pottery (from the Smithsonian)

Anthes, Bill. Native Moderns: American Indian Painting, 1940–1960. (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2006).

Bruce Bernstein, and Jackson Rushing. Modern by Tradition: American Indian Painting in the Studio Style. (Santa Fe, New Mexico: Museum of New Mexico Press, 1995).

J.J. Brody, Pueblo Indian Painting: Tradition and Modernism in New Mexico, 1900-1930. (Santa Fe, New Mexico: School of Advanced Research Press, 1997).

—. Anasazi and Pueblo Painting. (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1991).

—. Indian Painters and White Patrons. (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1971).

Ruth Bunzel, The Pueblo Potter: A Study of Creative Imagination in Primitive Art. (1911) (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 1972).

Ina Sizer Cassidy, Art and Artists of New Mexico. (Bureau of Publications, State of New Mexico, 1943).

Katherin L Chase, Indian Painters of the Southwest: The Deep Remembering. (Santa Fe, New Mexico: School of Advanced Research, 2002).

Dorothy Dunn, .American Indian Painting of the Southwest and Plains Area. (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1968).

—. “The Studio: 1932-1937: Fostering Indian Art as Art,” El Palacio vol. 83, no. 4, pp. 5-9.

Aaron Fry, “Local Knowledge and Art Historical Methodology: A New Perspective on Awa Tsireh and the San Ildefonso Easel Painting Movement,” Hemispheres: Visual Cultures of the Americas 1 (Spring, 2008): pp. 46-61.

Jessica Horton and Janet Catherine Berlo, “Pueblo Painting in 1932: Folding Narratives of Native Art into American Art History,” in John Davis, Jennifer A. Greenhill, and Jason D. LaFountain, editors, A Companion to American Art. (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2015).

Alice Marriott, Maria: The Potter of San Ildefonso (1948) (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987).

Elizabeth A Newsome, “Reflexivity and Subjectivity in Early Native American Painting: A Critique of Perspectives on the Traditional Style,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 25:3 (2001), pp.103-142.

Alfonzo Ortiz, The Tewa World: Space, Time, Being and Becoming in a Pueblo Society (Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago Press, 1969).

—, “Dual Organization as an Operational Concept in the Pueblo Southwest,” Ethnology, vol. 4, No. 4. (October 1965), pp. 389-396.

David W Penney. and Lisa Roberts. “America’s Pueblo Artists: Encounters on the Borderlands,” in W. Jackson Rushing III, editor, Native American Art in the Twentieth Century. (London: Routledge Press, 1999).

Susan Peterson, Living Tradition of Maria Martinez. First published in 1977. (Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International, 1989).

—. Pottery by American Indian Women: The Legacy of Generations. (New York, New York: Abbeville Press, 1997).

Rushing, W. Jackson, and Allan Houser. Allan Houser: An American Master (Chiricahua Apache, 1914-1994). (New York, New York: H.N. Abrams, 2004).

W. Jackson, Rushing, Native American Art in the Twentieth Century. (London: Routledge Press, 1999).

Sasha T. Scott, A Strange Mixture: The Art and Politics of Painting Pueblo Indians. (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2015).

Tryntje Van Ness Seymour, When the Rainbow Touches Down: The Artists and Stories Behind the Apache, Navajo, Rio Grande Pueblo, and Hopi Paintings in the William and Leslie Van Ness Denman Collection. (Phoenix, Arizona: Heard Museum, 1988).

Julie Solometo, “The Context and Process of Pueblo Mural Painting in the Historic Era,” Kiva vol. 76, no. 1 (2010), pp. 83-116.

Richard Spivey The Legacy of Maria Poveka Martinez. (Santa Fe, New Mexico: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2003).

R. Strickland, “Where Have All the Blue Deer Gone? Depth and Diversity in Post War Indian Painting,” American Indian Art Magazine v. 10 (Spring 1985), pp. 36-45

Jill Drayson Sweet, Dances of the Tewa Pueblo Indians: Expressions of new life. (Santa Fe, New Mexico: School for Advanced Research on the, 2004).

Clara Lee Tanner, Southwest Indian Painting: A Changing Art. (Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1971).

Sharyn Rohlfsen Udall, Contested Terrain: Myth and Meanings in Southwest Art. (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 1996).

Edwin L. Wade, “Straddling the Cultural Fence: The Conflict for Ethnic Artists within Pueblo Societies,” in The Arts of the North American Indian: Native Traditions in Evolution, ed. Edwin L. Wade (New York, New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1986), pp. 243-254.

The pueblo modernism of Ma Pe Wi

by DR. ADRIANA GRECI GREEN and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Velino Shije Herrera (Ma Pe Wi), <em>Design, Tree and Birds</em>, c. 1930, watercolor on paper, 25.25 x 17.75 inches (Newark Museum of Art, Gift of Amelia Elizabeth White, 1937, 37.216). Speakers: Dr. Adriana Greci Green and Dr. Beth Harris

Test your knowledge with a quiz

Key points

- In the early 20th century, there was new interest in Pueblo art and culture from modernist artists and the growing tourist industry. This came at a time when Indian Schools endangered Native American cultural traditions in an effort by the U.S. government to eliminate Native American ways of life and replace them with mainstream American culture.

- Beginning in 1918, informal painting classes were offered at the Santa Fe Indian School, and Velino Shije Herrera, along with fellow artists Awa Tsireh and Fred Kabotie, developed a genre of watercolor painting on paper that connected European styles with indigenous traditions of painting. Works like Design, Tree and Birds blended traditional symbolism and forms, with elements of modernist painting to create a hybrid for non-native audiences.

- As modernist Pueblo painting grew in popularity, some of its supporters also worked to protect the rights of the Puebloan peoples, supporting organizations like The Indian Rights Association, which helped raise awareness about the devastation created through government policies and practices.

Go deeper

This work of art at the Newark Museum

The Modernist-Inspired Watercolors of a Pioneering Pueblo Painter

The legacy of Indian Schools, at NPR

See Pueblo pottery painting from the 1930s

Explore primary sources on government policies towards Native Americans in the early 20th century

Learn more about the Indian Rights Association

Velino Shije Herrera at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

More to think about

Modern Native American artists like Clarissa Rizal and Jamie Okuma have blended their native traditions with contemporary style or meaning. What makes a work of art “traditional”? What other examples can you think of where an artist has blended their own culture with mainstream forms or techniques?

Northwest coast

Ceremonial belt (Kwakwaka’wakw)

by DR. AARON GLASS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Ceremonial belt (Kwakwaka’wakw), late 19th century, wood, cotton, paint, and iron (Field Museum, Chicago), an ARCHES video. Special thanks to Aaron Glass, the Bard Graduate Center, the U’mista Cultural Centre, and Corrine Hunt

Transformation masks

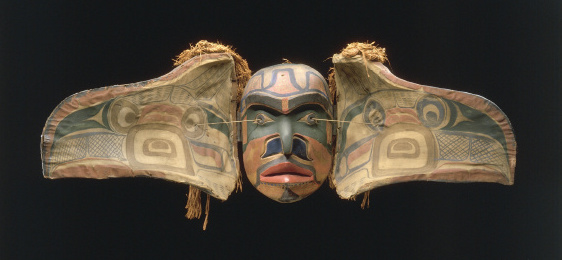

Transformation

Imagine a man standing before a large fire wearing the heavy eagle mask shown above and a long cedar bark costume on his body. He begins to dance, the firelight flickers and the feathers rustle as he moves about the room in front of hundreds of people. Now, imagine him pulling the string that opens the mask, he is transformed into something else entirely—what a powerful and dramatic moment!

Northwest Coast transformation masks manifest transformation, usually an animal changing into a mythical being or one animal becoming another. Masks are worn by dancers during ceremonies, they pull strings to open and move the mask—in effect, animating it. In the Eagle mask shown above from the collection of the American Museum of Natural History, you can see the wooden frame and netting that held the mask on the dancer’s head. When the cords are pulled, the eagle’s face and beak split down the center, and the bottom of the beak opens downwards, giving the impression of a bird spreading its wings (see image below). Transformed, the mask reveals the face of an ancestor.

A Transformation Mask at the Brooklyn Museum (below) shows a Thunderbird, but when opened it reveals a human face flanked on either side by two lightning snakes called sisiutl, and with another bird below it and a small figure in black above it.

A whale transformation mask, such as the one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (below), gives the impression that the whale is swimming. The mouth opens and closes, the tail moves upwards and downwards, and the flippers extend outwards but also retract inwards.

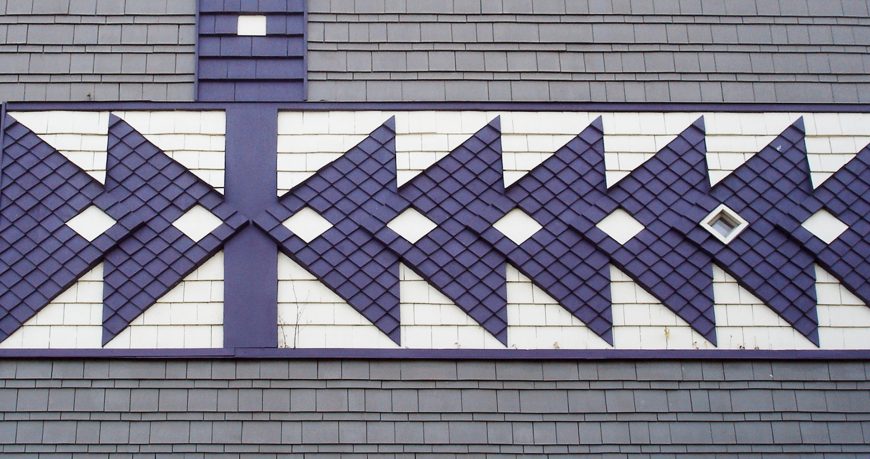

Transformation masks, like those belonging to the Kwakwaka’wakw (pronounced Kwak-wak-ah-wak, a Pacific Northwest Coast indigenous people) and illustrated here, are worn during a potlatch, a ceremony where the host displayed his status, in part by giving away gifts to those in attendance. These masks were only one part of a costume that also included a cloak made of red cedar bark. During a potlatch, Kwakwaka’wakw dancers perform wearing the mask and costume. The masks conveyed social position (only those with a certain status could wear them) and also helped to portray a family’s genealogy by displaying (family) crest symbols.

The Kwakwaka’wakw

Masks are not the same across the First Nations of the Northwest Coastal areas; here we focus solely on Kwakwaka’wakw transformation masks.