11.2: North America before c. 1500

- Page ID

- 67096

North America before c. 1500

Canada, the United States, Mesoamerica, and Central America

Native American / First Nations

Traces of sophisticated cultures remain across what is today the United States and Canada.

before 11,200 B.C.E. - c. 1500

Clovis culture

Clovis culture

The first clear evidence of human activity in North America are spear heads like this. They are called Clovis points. These spear tips were used to hunt large game. The period of the Clovis people coincides with the extinction of mammoths, giant sloth, camels and giant bison in North America. The extinction of these animals was caused by a combination of human hunting and climate change.

How did humans reach America?

North America was one of the last continents in the world to be settled by humans after about 15,000 BC. During the last Ice Age, water, which previously flowed off the land into the sea, was frozen up in vast ice sheets and glaciers so sea levels dropped. This exposed a land bridge that enabled humans to migrate through Siberia to Alaska. These early Americans were highly adaptable and Clovis points have been found throughout North America. It is remarkable that over such a vast area, the distinctive characteristics of the points hardly vary.

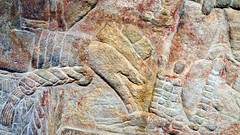

Typical Clovis points, like the example above, have parallel to slightly convex edges which narrow to a point. This shape is produced by chipping small, parallel flakes off both sides of a stone blade. Following this, the point is thinned on both sides by the removal of flakes which leave a central groove or “flute.” These flutes are the principal feature of Clovis or “fluted” points. They originate from the base which then has a concave outline and end about one-third along the length. The grooves produced by the removal of the flutes allow the point to be fitted to a wooden shaft of a spear.

The people who made Clovis points spread out across America looking for food and did not stay anywhere for long, although they did return to places where resources were plentiful.

Clovis points are sometimes found with the bones of mammoths, mastodons, sloth and giant bison. As the climate changed at the end of the last Ice Age, the habitats on which these animals depended started to disappear. Their extinction was inevitable but Clovis hunting on dwindling numbers probably contributed to their disappearance.

Although there are arguments in favor of pre-Clovis migrations to America, it is the “Paleo-Indian” Clovis people who can be most certainly identified as the probable ancestors of later Native North American peoples and cultures.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Additional resources:

B. Fagan, Ancient North America (London, 2005).

G. Haynes, The Early Settlement of North America: The Clovis Era (Cambridge, 2002).

G. Haynes (ed.), American Megafaunal Extinctions at the End of the Pleistocene (New York, 2009).

D. Meltzer, First Peoples in a New World: Colonizing Ice Age America(Berkeley, 2009).

S. Mithen, After the Ice: A Global Human History 20000-5000 BC (London, 2003).

Moundbuilders

Fort Ancient Culture: Great Serpent Mound

A serpent 1300 feet long

The Great Serpent Mound in rural, southwestern Ohio is the largest serpent effigy in the world. Numerous mounds were made by the ancient Native American cultures that flourished along the fertile valleys of the Mississippi, Ohio, Illinois, and Missouri Rivers a thousand years ago, though many were destroyed as farms spread across this region during the modern era. They invite us to contemplate the rich spiritual beliefs of the ancient Native American cultures that created them.

The Great Serpent Mound measures approximately 1,300 feet in length and ranges from one to three feet in height. The complex mound is both architectural and sculptural and was erected by settled peoples who cultivated maize, beans and squash and who maintained a stratified society with an organized labor force, but left no written records. Let’s take a look at both aerial and close-up views that can help us understand the mound in relationship to its site and the possible intentions of its makers.

Supernatural powers?

The serpent is slightly crescent-shaped and oriented such that the head is at the east and the tail at the west, with seven winding coils in between. The shape of the head perhaps invites the most speculation. Whereas some scholars read the oval shape as an enlarged eye, others see a hollow egg or even a frog about to be swallowed by wide, open jaws. But perhaps that lower jaw is an indication of appendages, such as small arms that might imply the creature is a lizard rather than a snake. Many native cultures in both North and Central America attributed supernatural powers to snakes or reptiles and included them in their spiritual practices. The native peoples of the Middle Ohio Valley in particular frequently created snake-shapes out of copper sheets.

The mound conforms to the natural topography of the site, which is a high plateau overlooking Ohio Brush Creek. In fact, the head of the creature approaches a steep, natural cliff above the creek. The unique geologic formations suggest that a meteor struck the site approximately 250-300 million years ago, causing folded bedrock underneath the mound.

Celestial hypotheses

Aspects of both the zoomorphic form and the unusual site have associations with astronomy worthy of our consideration. The head of the serpent aligns with the summer solstice sunset, and the tail points to the winter solstice sunrise. Could this mound have been used to mark time or seasons, perhaps indicating when to plant or harvest? Likewise, it has been suggested that the curves in the body of the snake parallel lunar phases, or alternatively align with the two solstices and two equinoxes.

Some have interpreted the egg or eye shape at the head to be a representation of the sun. Perhaps even the swallowing of the sun shape could document a solar eclipse. Another theory is that the shape of the serpent imitates the constellation Draco, with the Pole Star matching the placement of the first curve in the snake’s torso from the head. An alignment with the Pole Star may indicate that the mound was used to determine true north and thus served as a kind of compass.

Of note also is the fact that Halley’s Comet appeared in 1066, although the tail of the comet is characteristically straight rather than curved. Perhaps the mound served in part to mark this astronomical event or a similar phenomenon, such as light from a supernova. In a more comprehensive view, the serpent mount may represent a conglomerate of all celestial knowledge known by these native peoples in a single image.

Who built it?

Determining exactly which culture designed and built the effigy mound, and when, is a matter of ongoing inquiry. A broad answer may lie in viewing the work as being designed, built, and/or refurbished over an extended period of time by several indigenous groups. The leading theory is that the Fort Ancient Culture (1000-1650 C.E.) is principally responsible for the mound, having erected it in c. 1070 C.E. This mound-building society lived in the Ohio Valley and was influenced by the contemporary Mississippian culture (700-1550), whose urban center was located at Cahokia in Illinois. The rattlesnake was a common theme among the Mississippian culture, and thus it is possible that the Fort Ancient Culture appropriated this symbol from them (although there is no clear reference to a rattle to identify the species as such).

An alternative theory is that the Fort Ancient Culture refurbished the site c. 1070, reworking a preexisting mound built by the Adena Culture (c.1100 B.C.E.-200 C.E.) and/or the Hopewell Culture (c. 100 B.C.E.-550 C.E.). Whether the site was built by the Fort Ancient peoples, or by the earlier Adena or Hopewell Cultures, the mound is atypical. The mound contains no artifacts, and both the Fort Ancient and Adena groups typically buried objects inside their mounds. Although there are no graves found inside the Great Serpent Mound, there are burials found nearby, but none of them are the kinds of burials typical for the Fort Ancient culture and are more closely associated with Adena burial practices. Archaeological evidence does not support a burial purpose for the Great Serpent Mound.

Debate continues

Whether this impressive monument was used as a way to mark time, document a celestial event, act as a compass, serve as a guide to astrological patterns, or provide a place of worship to a supernatural snake god or goddess, we may never know with certainty. One scholar has recently suggested that the mound was a platform or base for totems or other architectural structures that are no longer extant, perhaps removed by subsequent cultures. All to say, scholarly debate continues, based on on-going archaeological evidence and geological research. But without a doubt, the mound is singular and significant in its ability to provide tangible insights into the cosmology and rituals of the ancient Americas.

Additional resources:

Great Serpent Mound at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Serpent Mound at the Ohio Historical Society

Mississippian shell neck ornament (gorget)

by DR. DAVID W. PENNEY, NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Gorget, c. 1250-1350, probably Middle Mississippian Tradition, whelk shell, 10 x 2 cm (National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, 18/853), a Seeing America video

Speakers: Dr. David Penney, Associate Director for Museum Scholarship, Exhibitions, and Public Engagement, National Museum of the American Indian and Dr. Beth Harris

Additional resources

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Ancestral Puebloan

Mesa Verde

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\):

Mesa Verde and the preservation of Ancestral Puebloan heritage ARCHES: At Risk Cultural Heritage Education Series Speakers: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Steven Zucker

Wanted: stunning view

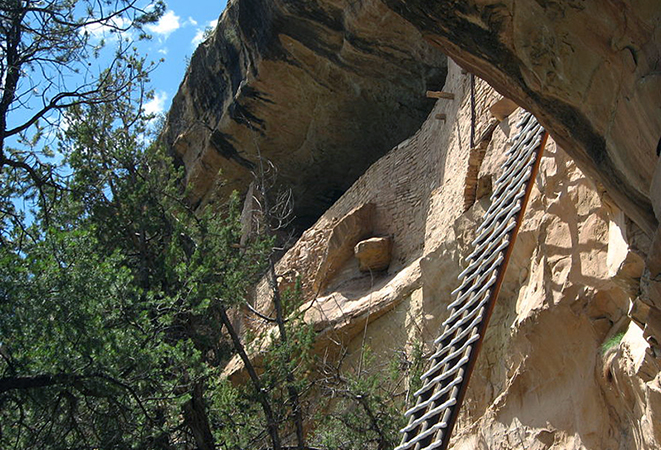

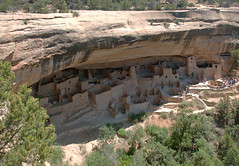

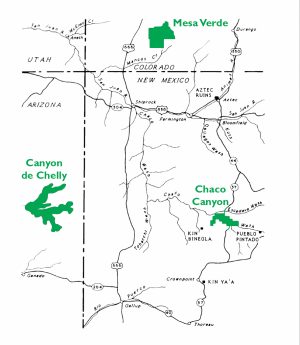

Imagine living in a home built into the side of a cliff. The Ancestral Puebloan peoples (formerly known as the Anasazi) did just that in some of the most remarkable structures still in existence today. Beginning after 1000-1100 C.E., they built more than 600 structures (mostly residential but also for storage and ritual) into the cliff faces of the Four Corners region of the United States (the southwestern corner of Colorado, northwestern corner of New Mexico, northeastern corner of Arizona, and southeastern corner of Utah). The dwellings depicted here are located in what is today southwestern Colorado in the national park known as Mesa Verde (“verde” is Spanish for green and “mesa” literally means table in Spanish but here refers to the flat-topped mountains common in the southwest).

The most famous residential sites date to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The Ancestral Puebloans accessed these dwellings with retractable ladders, and if you are sure footed and not afraid of heights, you can still visit some of these sites in the same way today.

To access Mesa Verde National Park, you drive up to the plateau along a winding road. People come from around the world to marvel at the natural beauty of the area as well as the archaeological remains, making it a popular tourist destination.

The twelfth- and thirteenth-century structures made of stone, mortar, and plaster remain the most intact. We often see traces of the people who constructed these buildings, such as hand or fingerprints in many of the mortar and plaster walls.

Ancestral Puebloans occupied the Mesa Verde region from about 450 C.E. to 1300 C.E. The inhabited region encompassed a far larger geographic area than is defined now by the national park, and included other residential sites like Hovenweep National Monument and Yellow Jacket Pueblo. Not everyone lived in cliff dwellings. Yellow Jacket Pueblo was also much larger than any site at Mesa Verde. It had 600–1200 rooms, and 700 people likely lived there (see link below). In contrast, only about 125 people lived in Cliff Palace (largest of the Mesa Verde sites), but the cliff dwellings are certainly among the best-preserved buildings from this time.

Cliff palace

The largest of all the cliff dwellings, Cliff Palace, has about 150 rooms and more than twenty circular rooms. Due to its location, it was well protected from the elements. The buildings ranged from one to four stories, and some hit the natural stone “ceiling.” To build these structures, people used stone and mud mortar, along with wooden beams adapted to the natural clefts in the cliff face. This building technique was a shift from earlier structures in the Mesa Verde area, which, prior to 1000 C.E., had been made primarily of adobe (bricks made of clay, sand and straw or sticks). These stone and mortar buildings, along with the decorative elements and objects found inside them, provide important insights into the lives of the Ancestral Puebloan people during the thirteenth century.

At sites like Cliff Palace, families lived in architectural units, organized around kivas (circular, subterranean rooms). A kiva typically had a wood-beamed roof held up by six engaged support columns made of masonry above a shelf-like banquette. Other typical features of a kiva include a firepit (or hearth), a ventilation shaft, a deflector (a low wall designed to prevent air drawn from the ventilation shaft from reaching the fire directly), and a sipapu, a small hole in the floor that is ceremonial in purpose. They developed from the pithouse, also a circular, subterranean room used as a living space.

Kivas continue to be used for ceremonies today by Puebloan peoples though not those within Mesa Verde National Park. In the past, these circular spaces were likely both ceremonial and residential. If you visit Cliff Palace, you will see the kivas without their roofs (see above), but in the past they would have been covered, and the space around them would have functioned as a small plaza.

Connected rooms fanned out around these plazas, creating a housing unit. One room, typically facing onto the plaza, contained a hearth. Family members most likely gathered here. Other rooms located off the hearth were most likely storage rooms, with just enough of an opening to squeeze your arm through a hole to grab anything you might need. Cliff Palace also features some unusual structures, including a circular tower. Archaeologists are still uncertain as to the exact use of the tower.

Painted murals

The builders of these structures plastered and painted murals, although what remains today is fairly fragmentary. Some murals display geometric designs, while other murals represent animals and plants.

For example, Mural 30, on the third floor of a rectangular “tower” (more accurately a room block) at Cliff Palace, is painted red against a white wall. The mural includes geometric shapes that are thought to portray the landscape. It is similar to murals inside of other cliff dwellings including Spruce Tree House and Balcony House. Scholars have suggested that the red band at the bottom symbolizes the earth while the lighter portion of the wall symbolizes the sky. The top of the red band, then, forms a kind of horizon line that separates the two. We recognize what look like triangular peaks, perhaps mountains on the horizon line. The rectangular element in the sky might relate to clouds, rain or to the sun and moon. The dotted lines might represent cracks in the earth.

The creators of the murals used paint produced from clay, organic materials, and minerals. For instance, the red color came from hematite (a red ocher). Blue pigment could be turquoise or azurite, while black was often derived from charcoal. Along with the complex architecture and mural painting, the Ancestral Puebloan peoples produced black-on-white ceramics and turquoise and shell jewelry (goods were imported from afar including shell and other types of pottery). Many of these high-quality objects and their materials demonstrate the close relationship these people had to the landscape. Notice, for example, how the geometric designs on the mugs above appear similar to those in Mural 30 at Cliff Palace.

Why build here?

From 500–1300 C.E., Ancestral Puebloans who lived at Mesa Verde were sedentary farmers and cultivated beans, squash, and corn. Corn originally came from what is today Mexico at some point during the first millennium of the Common Era. Originally most farmers lived near their crops, but this shifted in the late 1100s when people began to live near sources of water, and often had to walk longer distances to their crops.

So why move up to the cliff alcoves at all, away from water and crops? Did the cliffs provide protection from invaders? Were they defensive or were there other issues at play? Did the rock ledges have a ceremonial or spiritual significance? They certainly provide shade and protection from snow. Ultimately, we are left only with educated guesses—the exact reasons for building the cliff dwellings remain unknown to us.

Why were the cliffs abandoned?

The cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde were abandoned around 1300 C.E. After all the time and effort it took to build these beautiful dwellings, why did people leave the area? Cliff Palace was built in the twelfth century, why was it abandoned less than a hundred years later? These questions have not been answered conclusively, though it is likely that the migration from this area was due to either drought, lack of resources, violence or some combination of these. We know, for instance, that droughts occurred from 1276 to 1299. These dry periods likely caused a shortage of food and may have resulted in confrontations as resources became more scarce. The cliff dwellings remain, though, as compelling examples of how the Ancestral Puebloans literally carved their existence into the rocky landscape of today’s southwestern United States.

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Additional resources:

Yellow Jacket Pueblo reconstruction

Janet Catherine Berlo and Ruth B. Phillips, Native North American Art, 2 ed. Oxford History of Art series (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Elizabeth A. Newsome and Kelley Hays-Gilpin, “Spectatorship and Performance in Mural Painting, AD 1250–1500,” Religious Transformation in the Late Pre-Hispanic Pueblo World, eds. Donna Glowacki and Scott Van Keuren, Amerind Studies in Archaeology (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 2011).

David Grant Noble, ed., The Mesa Verde World: Explorations in Ancestral Pueblo Archaeology (Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press, 2006).

David W. Penney, North American Indian Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2004).

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

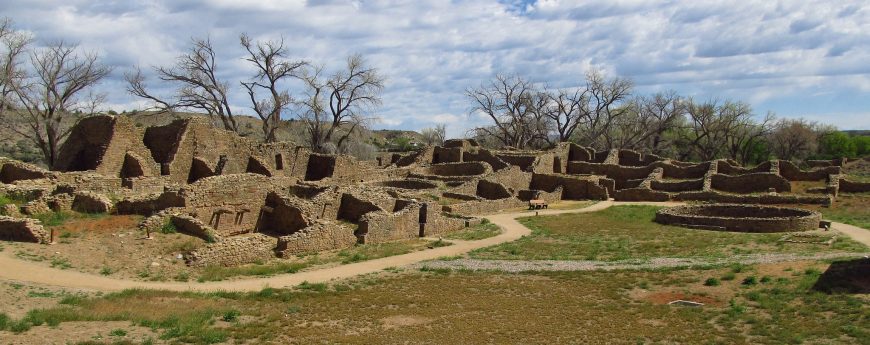

Introduction to Chaco Canyon

New Mexico is known as the “land of enchantment.” Among its many wonders, Chaco Canyon stands out as one of the most spectacular. Part of Chaco Culture National Historical Park, Chaco Canyon is among the most impressive archaeological sites in the world, receiving tens of thousands of visitors each year. Chaco is more than just a tourist site however, it is also sacred land. Pueblo peoples like the Hopi, Navajo, and Zuni consider it a home of their ancestors.

The canyon is vast and contains an impressive number of structures—both big and small—testifying to the incredible creativity of the people who lived in the Four Corners region of the U.S. between the 9th and 12th centuries. Chaco was the urban center of a broader world, and the ancestral Puebloans who lived here engineered striking buildings, waterways, and more.

Chaco is located in a high, desert region of New Mexico, where water is scarce. The remains of dams, canals, and basins suggest that Chacoans spent a considerable amount of their energy and resources on the control of water in order to grow crops, such as corn. Today, visitors have to imagine the greenery that would have filled the canyon.

Astronomical observations clearly played an important role in Chaco life, and they likely had spiritual significance. Petroglyphs found in Chaco Canyon and the surrounding area reveal an interest in lunar and solar cycles, and many buildings are oriented to align with winter and summer solstices.

Great Houses

“Downtown Chaco” features a number of “Great Houses” built of stone and wood. Most of these large complexes have Spanish names, given to them during expeditions, such as one sponsored by the U.S. army in 1849, led by Lt. James Simpson. Carabajal, Simpson’s guide, was Mexican, which helps to explain some of the Spanish names. Great Houses also have Navajo names, and are described in Navajo legends. Tsebida’t’ini’ani (Navajo for “covered hole”), nastl’a kin (Navajo for “house in the corner”), and Chetro Ketl (a name of unknown origin) all refer to one great house, while Pueblo Bonito (Spanish for “pretty village”) and tse biyaa anii-ahi (Navajo for “leaning rock gap”) refer to another.

Pueblo Bonito is among the most impressive of the Great Houses. It is a massive D-shaped structure that had somewhere between 600 and 800 rooms. It was multistoried, with some sections reaching as high as four stories. Some upper floors contained balconies.

There are many questions that we are still trying to answer about this remarkable site and the people who lived here. A Great House like Pueblo Bonito includes numerous round rooms, called kivas. This large architectural structure included three great kivas and thirty-two smaller kivas. Great kivas are far larger in scale than the others, and were possibly used to gather hundreds of people together. The smaller kivas likely functioned as ceremonial spaces, although they were likely multi-purpose rooms.

Among the many remarkable features of this building are its doorways, sometimes aligned to give the impression that you can see all the way through the building. Some doorways have a T shape, and T-shaped doors are also found at other sites across the region. Research is ongoing to determine whether the T-shaped doors suggest the influence of Chaco or if the T-shaped door was a common aesthetic feature in this area, which the Chacoans then adopted.

Recently, testing of the trees (dendroprovenance) that were used to construct these massive buildings has demonstrated that the wood came from two distinct areas more than 50 miles away: one in the San Mateo Mountains, the other the Chuska Mountains. About 240,000 trees would have been used for one of the larger Great Houses.

Chacoan Cultural Interactions

Traditionally, we tend to separate Mesoamerica and the American Southwest, as if the peoples who lived in these areas did not interact. We now know this is misleading, and was not the case.

Chacoan culture expanded far beyond the confines of Chaco Canyon. Staircases leading out of the canyon allowed people to climb the mesas and access a vast network of roads that connected places across great distances, such as Great Houses in the wider region. Aztec Ruins National Monument (not to be confused with ruins that belonged to the Aztecs of Mesoamerica) in New Mexico is another ancestral Puebloan site with many of the same architectural features we see at Chaco, including a Great House and T-shaped doorways.

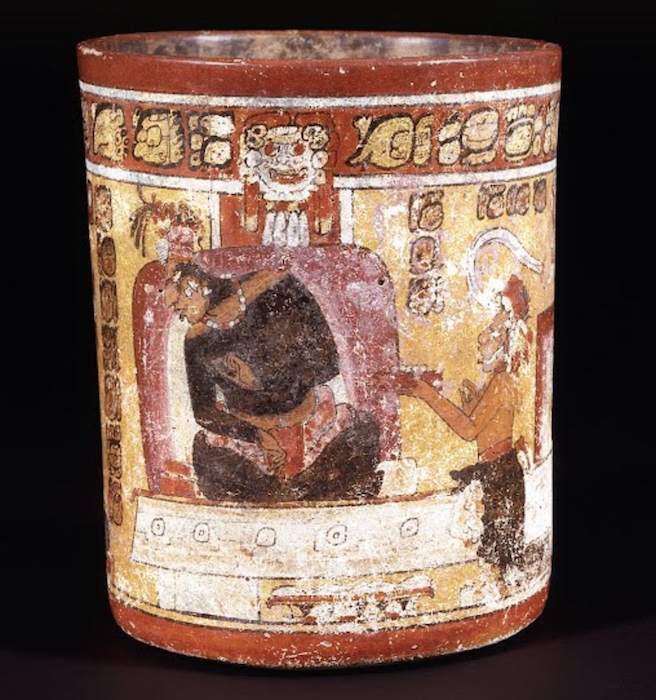

Archaeological excavations have uncovered remarkable objects that animated Chacoan life and reveal Chaco’s interactions with peoples outside the Southwestern United States. More than 15,000 artifacts have been unearthed during different excavations at Pueblo Bonito alone, making it one of the best understood spaces at Chaco. Many of these objects speak to the larger Chacoan world, as well as Chaco’s interactions with cultures farther away. In one storage room within Pueblo Bonito, pottery sherds had traces of cacao imported from Mesoamerica. These black-and-white cylindrical vessels were likely used for drinking cacao, similar to the brightly painted Maya vessels used for a similar purpose.

The remains of scarlet macaws, birds native to an area in Mexico more than 1,000 miles away, also reveal the trade networks that existed across the Mesoamerican and Southwestern world. We know from other archaeological sites in the southwest that there were attempts to breed these colorful birds, no doubt in order to use their colorful feathers as status symbols or for ceremonial purposes. A room with a thick layer of guano (bird excrement) suggests that an aviary also existed within Pueblo Bonito. Copper bells found at Chaco also come from much further south in Mexico, once again testifying to the flourishing trade networks at this time. Chaco likely acquired these materials and objects in exchange for turquoise from their own area, examples of which can be found as far south as the Yucatan Peninsula.

Current Threats to Chaco

The world of Chaco is threatened by oil drilling and fracking. After President Theodore Roosevelt passed the Antiquities Act of 1906, Chaco was one of the first sites to be made a national monument. Chaco Canyon is also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Chacoan region extended far beyond this center, but unfortunately the Greater Chacoan Region does not fall under the protection of the National Park Service or UNESCO. Much of the Greater Chaco Region needs to be surveyed, because there are certainly many undiscovered structures, roads, and other findings that would help us learn more about this important culture. Beyond its importance as an extraordinary site of global cultural heritage, Chaco has sacred and ancestral significance for many Native Americans. Destruction of the Greater Chaco Region erases an important connection to the ancestral past of Native peoples, and to the present and future that belongs to all of us.

Additional resources:

Chaco Canyon UNESCO World Heritage Site webpage

“Unexpected Wood Source for Chaco Canyon Great Houses” from the University of Arizona

Stephen H. Lekson, ed. The Architecture of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2007).

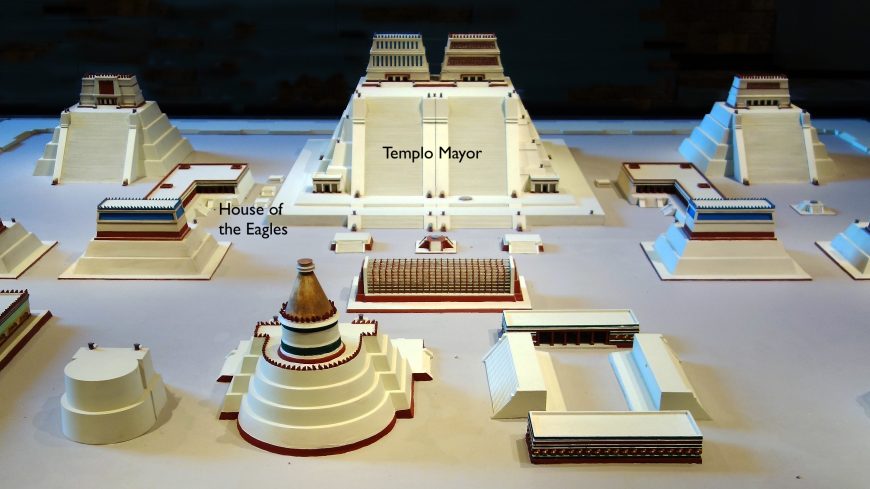

Mesoamerica

Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, and El Salvador

Before 7,000 B.C.E - c. 1500 C.E.

A beginner's guide to Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica, an introduction

Avocado, tomato, and chocolate. You are likely familiar with at least some of these food items. Did you know that they all originally come from Mexico, and are all based on Nahuatl words (ahuacatl, tomatl, and chocolatl) that were eventually adopted by the English language?

Nahuatl is the language spoken by the Nahua ethnic group that is found today in Mexico, but with deep historical roots. You might know one Nahua group: the Aztecs, more accurately called the Mexica. The Mexica were one of many Mesoamerican cultural groups that flourished in Mexico prior to the arrival of Europeans in the sixteenth century.

Where was Mesoamerica?

Mesoamerica refers to the diverse civilizations that shared similar cultural characteristics in the geographic areas comprising the modern-day countries of Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. Some of the shared cultural traits among Mesoamerican peoples included a complex pantheon of deities, architectural features, a ballgame, the 260-day calendar, trade, food (especially a reliance on maize, beans, and squash), dress, and accoutrements (such as earspools).

Some of the most well-known Mesoamerican cultures are the Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, Teotihuacan, Mixtec, and Mexica (or Aztec). The geography of Mesoamerica is incredibly diverse—it includes humid tropical areas, dry deserts, high mountainous terrain, and low coastal plains. An anthropologist named Paul Kirchkoff first used the term “Mesoamerica” (meso is Greek for “middle” or “intermediate”) in 1943 to designate these geographical areas as having shared cultural traits prior to the invasion of Europeans, and the term has remained.

Typically when we discuss Mesoamerican art we are referring to art made by peoples in Mexico and much of Central America. When people mention Native North American art, they are usually referring to indigenous peoples in the U.S. and Canada, even though these countries are technically all part of North America. More recently, archaeologists and art historians have considered connections between the Southwestern and Southeastern U.S. and Mesoamerica, an area sometimes called either the Greater Southwest or Greater Mesoamerica. Focusing on these connections demonstrates how people were in contact with one another through trade, shared beliefs, migration, or conflict. Ball courts, for instance, are found in Arizona sites such as the Pueblo Grande of the Hohokam. It is important to remember that modern-day geographic terms—like Mesoamerica or the Southwestern U.S.—are recent designations.

This essay generalizes about Mesoamerican cultures, but keep in mind that each possessed unique qualities and cultural differences. Mesoamerica was not homogenous.

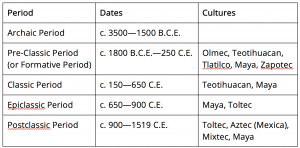

When was Mesoamerica?

Art historians and archaeologists divide Mesoamerican history into distinct periods and some of these periods are then further divided into the sub-periods—early, middle, and late.

You might also encounter the term Pre-Columbian, which is a term designating indigenous cultures prior to the arrival of Columbus. It includes those in Mesoamerica, as well as in South America and the Caribbean. This term is problematic for several reasons, and is explored in another essay.

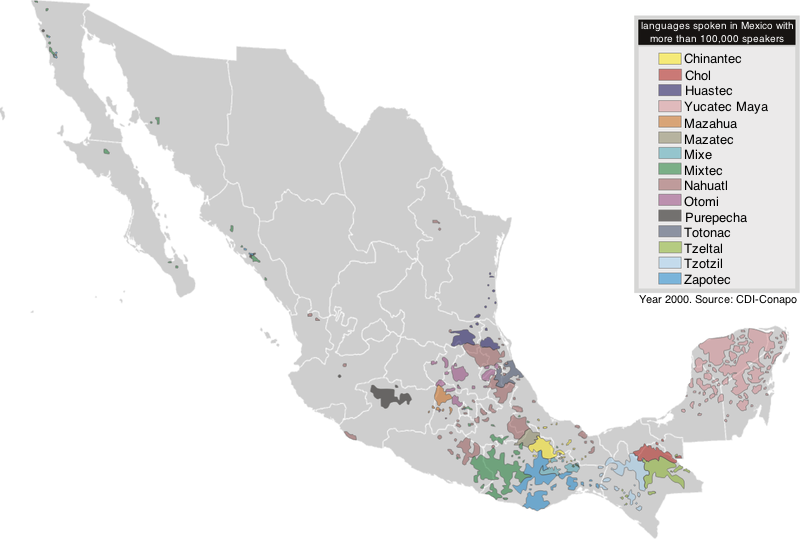

What language did people speak?

There was no single language that united the peoples of Mesoamerica. Linguists believe that Mesoamericans spoke more than 125 different languages. For instance, Maya peoples did not speak “Mayan”, but could have spoken Yucatec Maya, K’iche, or Tzotzil among many others. The Mexica belonged to the bigger Nahua ethnic group, and therefore spoke Nahuatl.

To students learning about Mesoamerica for the first time, the incredible diversity of people, languages, and even deities can be overwhelming. I recall my first Mesoamerican art history class vividly. I was intimidated by my lack of familiarity with different Mesoamerican words, languages, and cultural groups. By the end of the semester I was proud that I could differentiate between the Zapotec and Mixtec, and could spell Tlaloc. It took me a few more years to be able to spell and pronounce words like Tlacaxipehualiztli (Tla-cawsh-ee-pay-wal-eeezt-li) or Huitzilopochtli (Wheat-zil-oh-poach-lee).

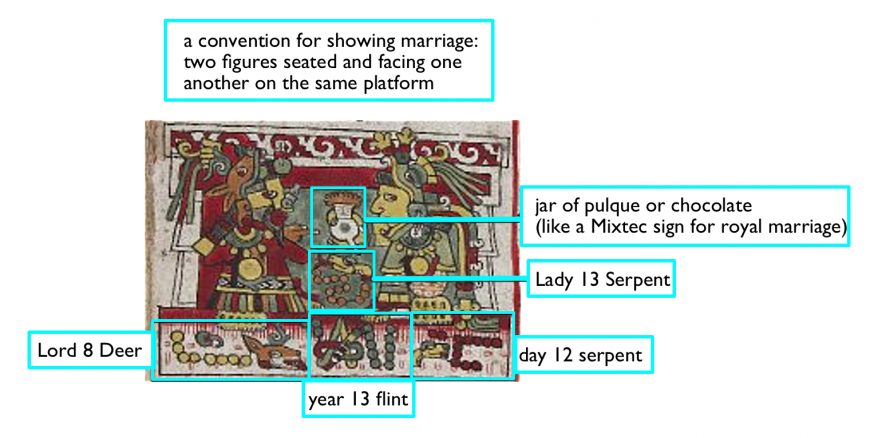

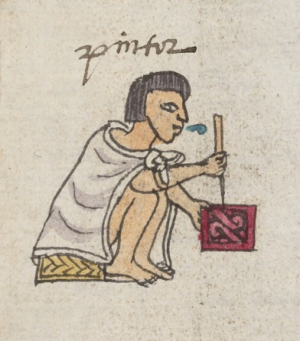

Writing

Mesoamerican writing systems vary by culture. Rebus writing (writing with images) was common among many groups, like the Nahua and Mixtec. Imagine drawing an eye, a heart, and an apple. You’ve just used rebus writing to communicate “I love apples” to anyone familiar with these symbols. Many visual writing systems in Mesoamerica functioned similarly—although the previous example was simplified for the sake of clarity. You might encounter the phrases “writing without words” or “writing with signs” used to describe many writing systems in Mesoamerica. It is also called pictographic, ideographic, or picture writing.

Only the Maya used a writing system like ours, where signs like letters designate sounds and syllables, and combined together to create words. Maya hieroglyphic writing is logographic, which means it uses a sign (think of a picture, symbol, or a letter) to communicate a syllable or a word.

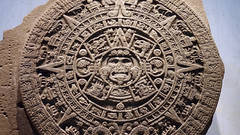

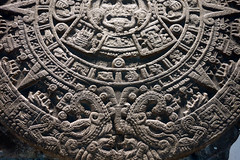

The 260-day ritual calendar vs. the 365-day calendar

Other shared features among Mesoamerican peoples were the 260-day and 365-day calendars. The 260-day calendar was a ritual calendar, with 20 months of 13 days. Based on the sun, the 365-day calendar had 18 months of 20 days, with five “extra” nameless days at the end. It was the count of time used for agriculture.

Imagine both of these calendars as interlocking wheels. Every 52 years they completed a full cycle, and during this time special rituals commemorated the cycle. For example, the Mexica celebrated the New Fire Ceremony as a period of renewal. These cycles were understood as life cycles, and so reflect creation, death, and rebirth. The Maya (especially during the Classic period), also used a Long Count calendar in addition to the two already mentioned (rather than a cyclical calendar, the Long Count marked time as if along an extended line that does not repeat).

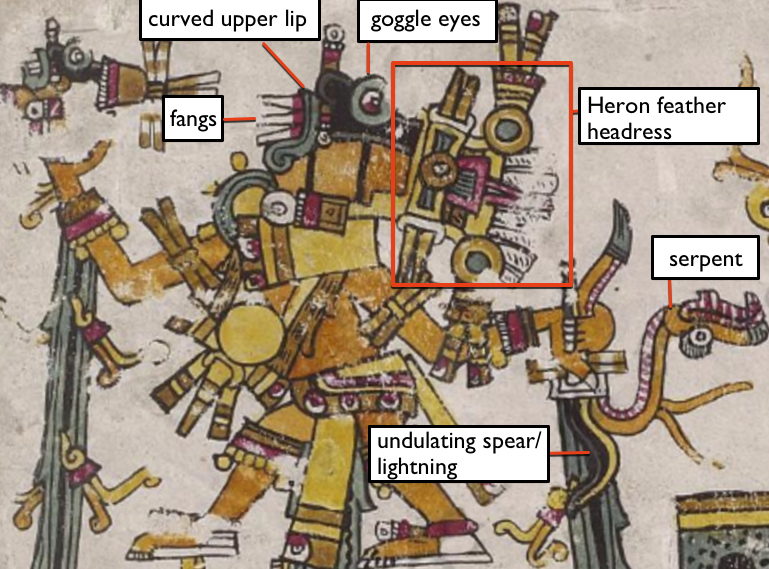

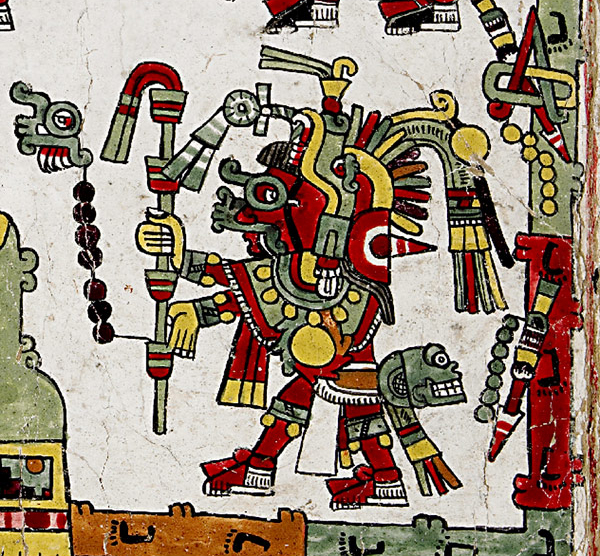

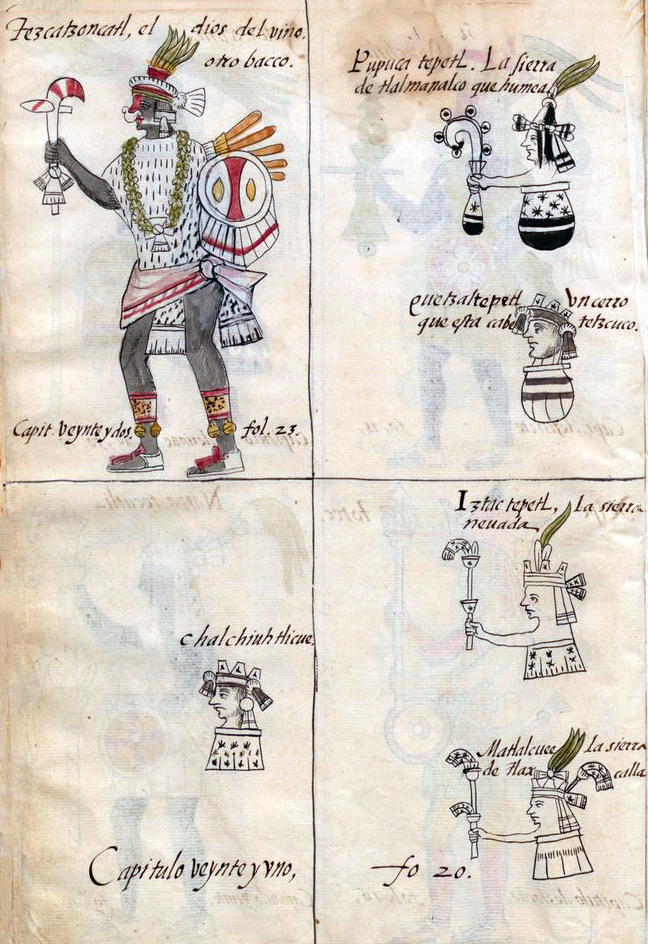

Religion and pantheon of gods

A complex pantheon of gods existed within each Mesoamerican culture. Many groups shared similar deities, although there was a great deal of variation. Deities that had important roles across Mesoamerica included a storm/rain god and a feathered serpent deity. Among the Mexica, this storm/rain god was known as Tlaloc, and the feathered serpent deity was known as Quetzalcoatl. The Maya referred to their storm/rain deity as Chaac (there are multiple spellings). The equivalent of Quetzalcoatl among different Maya groups included Kukulkan (Yucatec Maya) and Q’uq’umatz (K’iche Maya). Cocijo is the Zapotec equivalent of the storm/rain god. Many artworks exist that show these two deities with similar features. The storm/rain deity often has goggle eyes and an upturned mouth/snout. Feathered serpent deities typically showed serpent features paired with feathers.

It is difficult to generalize about Mesoamerican religious beliefs and cosmological ideas because they were so complex. Throughout Mesoamerica, there was a general belief in the universe’s division along two axes: one vertical, the other horizontal. At the center, where these two axes meet, is the axis mundi, or the center (or navel) of the universe. On the horizontal plane, four directions branch off from the axis mundi. Think of the four cardinal directions (north, south, east, and west). On the vertical plane, we generally find the world split into three major realms: the celestial, terrestrial, and underworld.

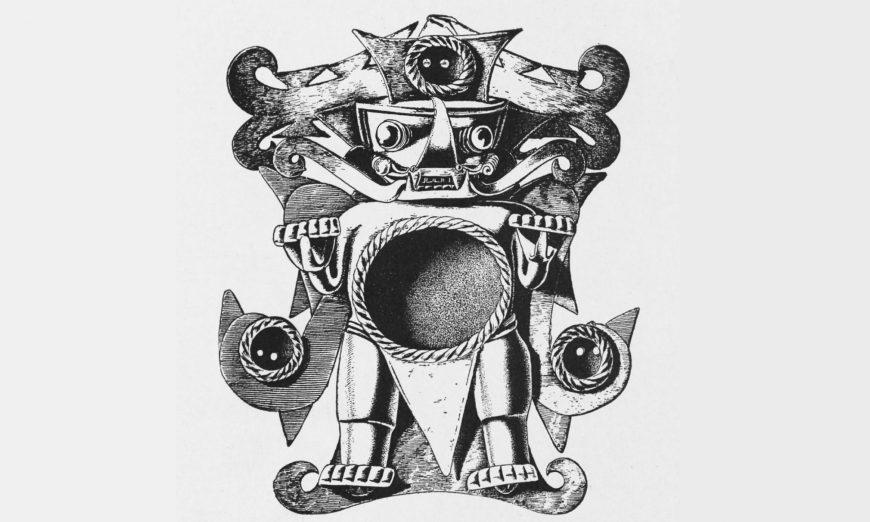

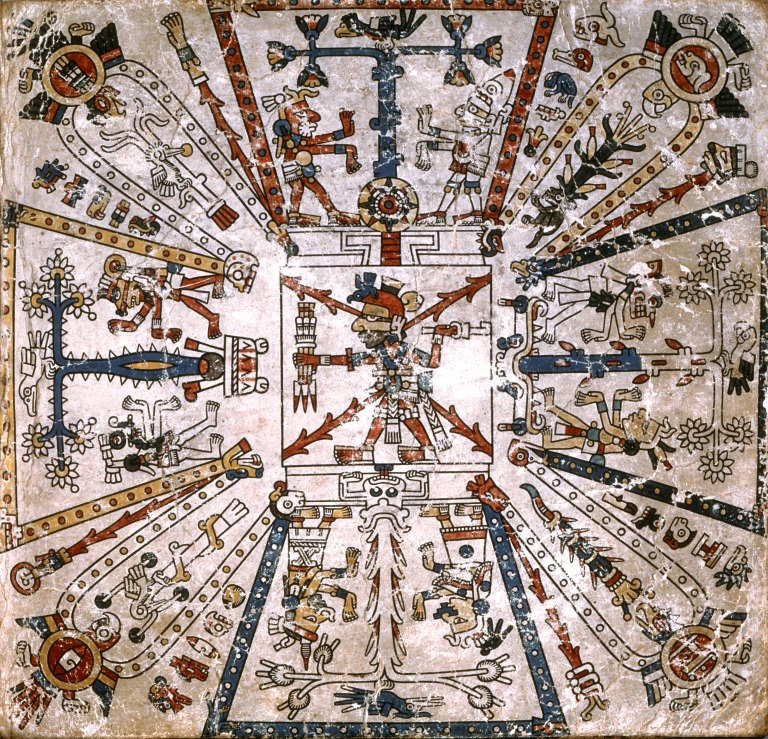

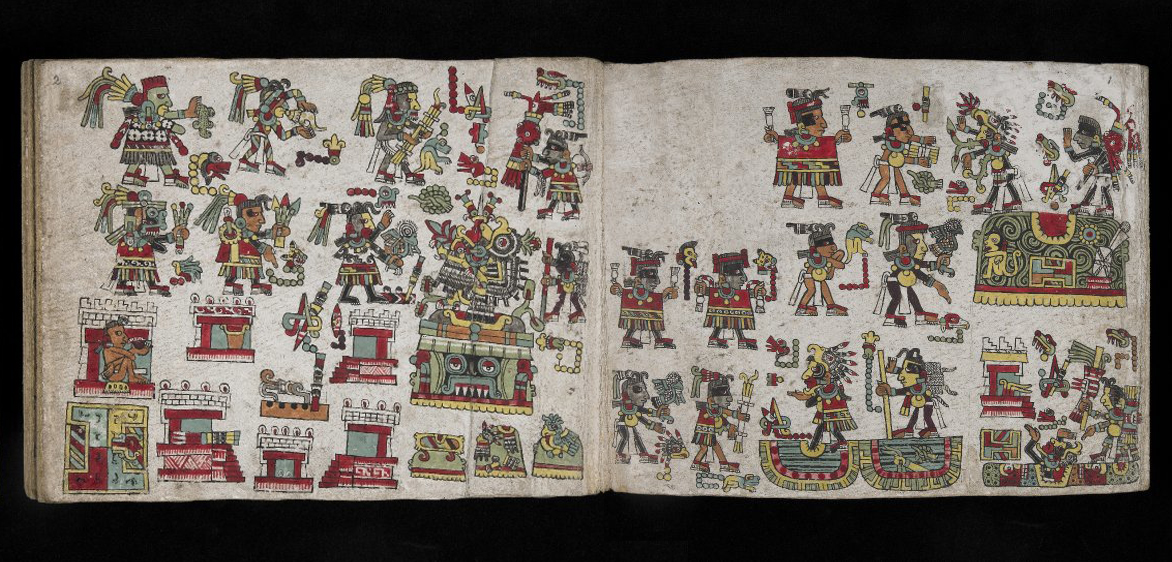

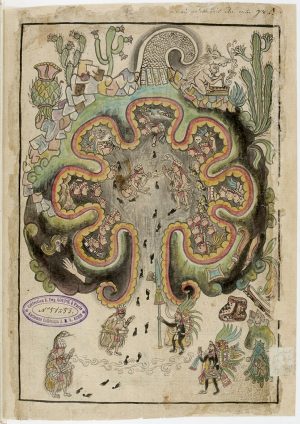

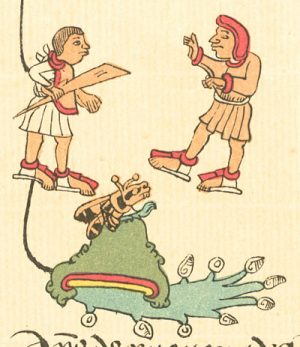

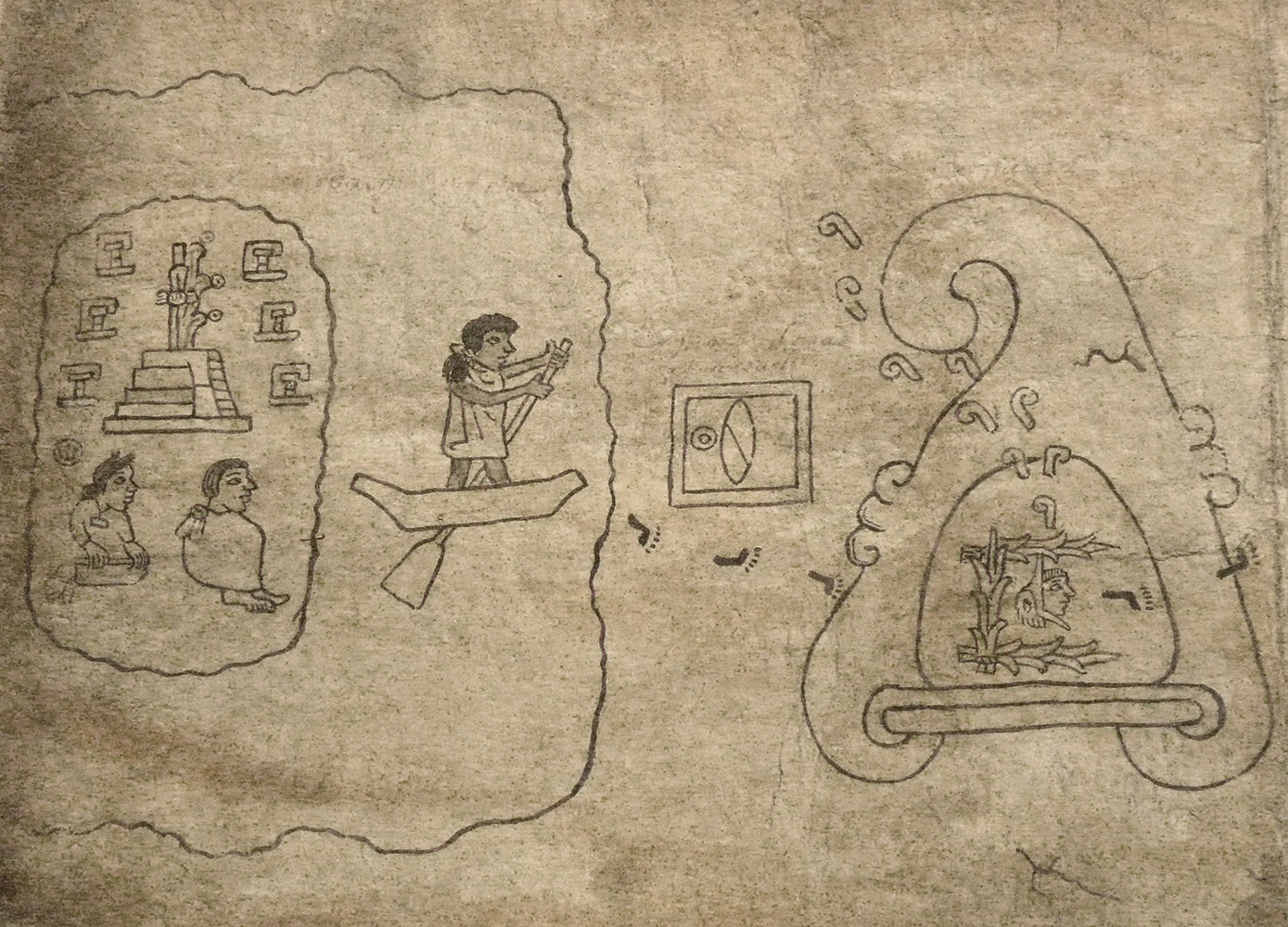

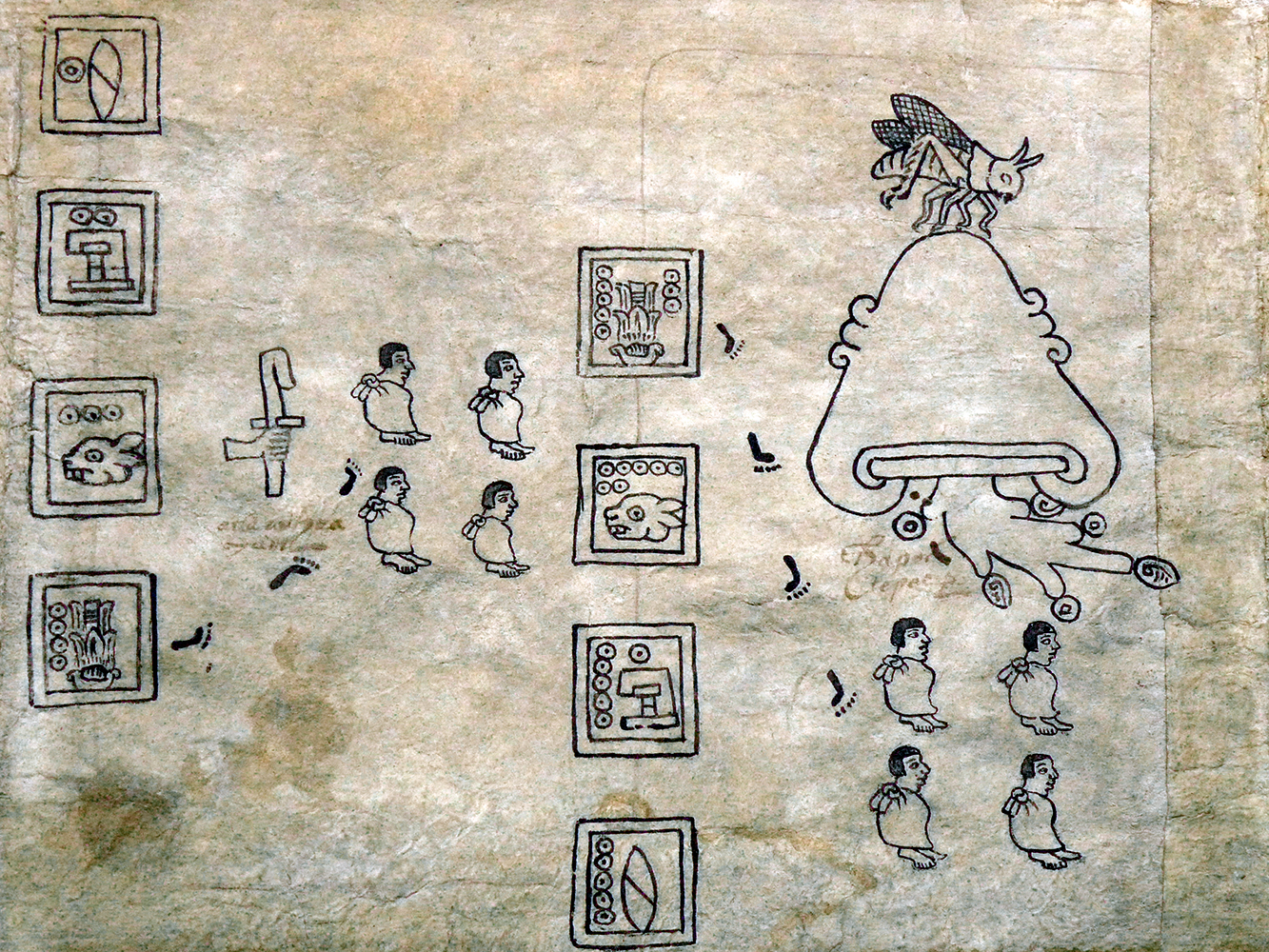

One Mexica example helps to clarify this complex cosmological system. An image in the Codex Féjervary-Mayer displays the cosmos’s horizontal axis. In the center is the deity Xiuhtecuhtli (a fire god), standing in the place of the axis mundi. Four nodes (what look almost like trapezoidal petals) branch off from his position, creating a shape called a Maltese Cross. East (top) is associated with red, south (right) with green, west (bottom) with blue, and north (left) with yellow. A specific plant and bird accompany each world direction: blue tree and quetzal (east), cacao and parrot (south), maize and blue-painted bird (west), and cactus and eagle (north). Two figures flank the plant in each arm of the cross. Together, these figures and Xiuhtecuhtli represent the Nine Lords of the Night. This cosmogram describes how the Mexica conceived of the universe.

The ballgame

Peoples across Mesoamerica, beginning with the Olmecs, played a ritual sport known as the ballgame. Ballcourts were often located in a city’s sacred precinct, emphasizing the importance of the game. Solid rubber balls were passed between players (no hands allowed!), with the goal of hitting them through markers. Players wore padded garments to protect their bodies from the hard ball.

The meanings of the ballgame were many and varied. It could symbolize a range of larger cosmological ideas, including the movement of the sun through the underworld every night. War captives also played the game against members of a winning city or group, with the game symbolizing their defeat in war. Sometimes a game was even played instead of going to war.

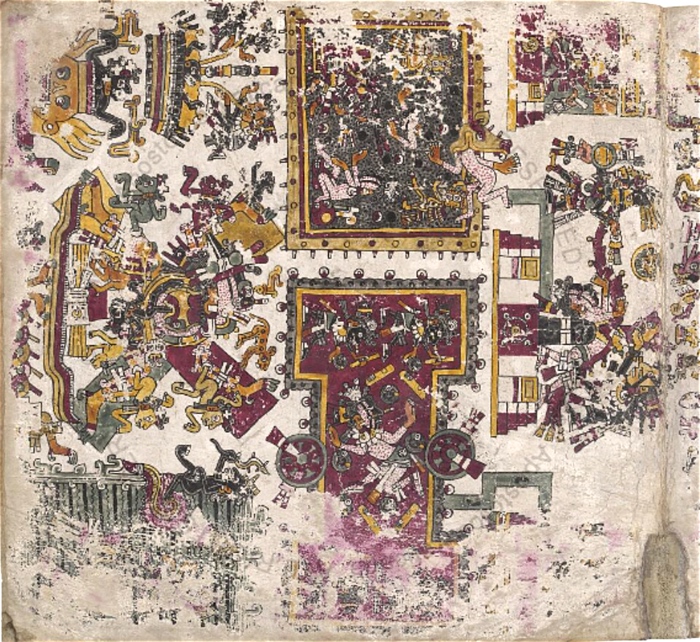

Numerous objects display aspects of the ballgame, attesting to its significant role across Mesoamerica. We have examples of clay sculptures of ballgames occurring on courts. Ballplayers are also frequent subjects in Maya painted ceramic vessels and sculptures. Stone reliefs at El Tajin and Chichen Itza depict different moments of a ballgame culminating in ritual sacrifice. Painted pictorial codices, such as the Codex Borgia (above), display I-shaped ballcourts, and stone depictions of ballgame clothing have been found. Today, people in Mexico still play a version of the ballgame.

Mesoamerican societies continue to impress us with their sophistication and accomplishments, notably their artistic achievements. Our understanding continues to expand with ongoing research and archaeological excavations. Recent excavations in Mexico City, for instance, uncovered a new monumental Mexica sculpture buried with some of the most unique objects we’ve ever seen in Mexica art. With these discoveries, our understanding of the Mexica will no doubt grow and change.

Additional resources:

The Mesoamerican Ballgame on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

The Ancient Future: Mesoamerican and Andean Timekeeping (Dumbarton Oaks)

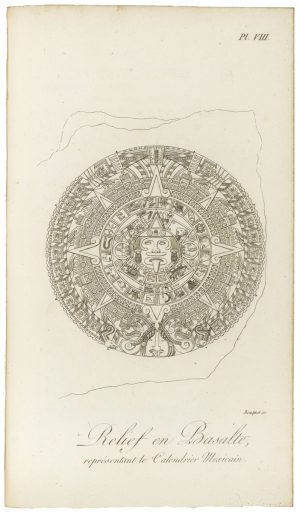

The Mesoamerican Calendar

We think of calendars as utilitarian—as tools that we all use every day to organize our time. But calendars also tell us a great deal about how the cultures that produce and use them understand and structure their world.

Before Spanish conquerors invaded the Americas in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Indigenous peoples of ancient Mexico, Guatemala, Belize and Honduras—an area known today as Mesoamerica—developed cultures over more than three millennia that were distinctive but that also held many ideas in common. Some of the features that they shared include the presence of ballcourts where a game was played using a heavy rubber ball, the development of complex religions with elaborate pantheons of deities, and, in works of art, a shared understanding of the importance of materials like greenstone and precious feathers.

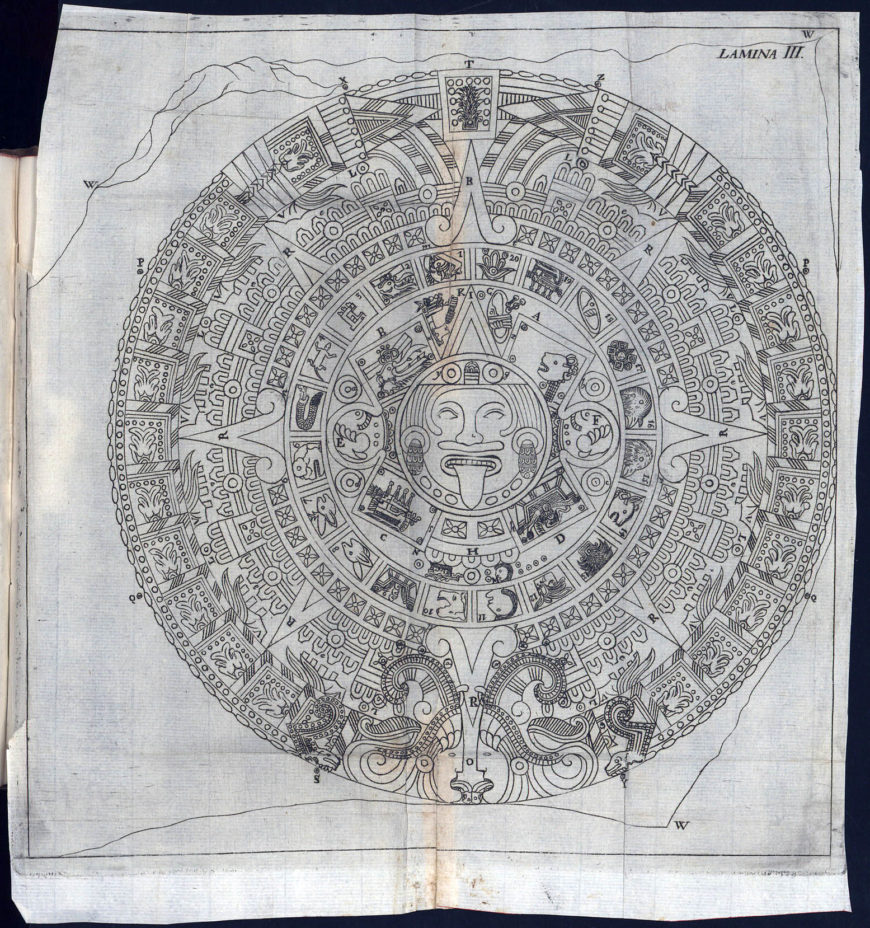

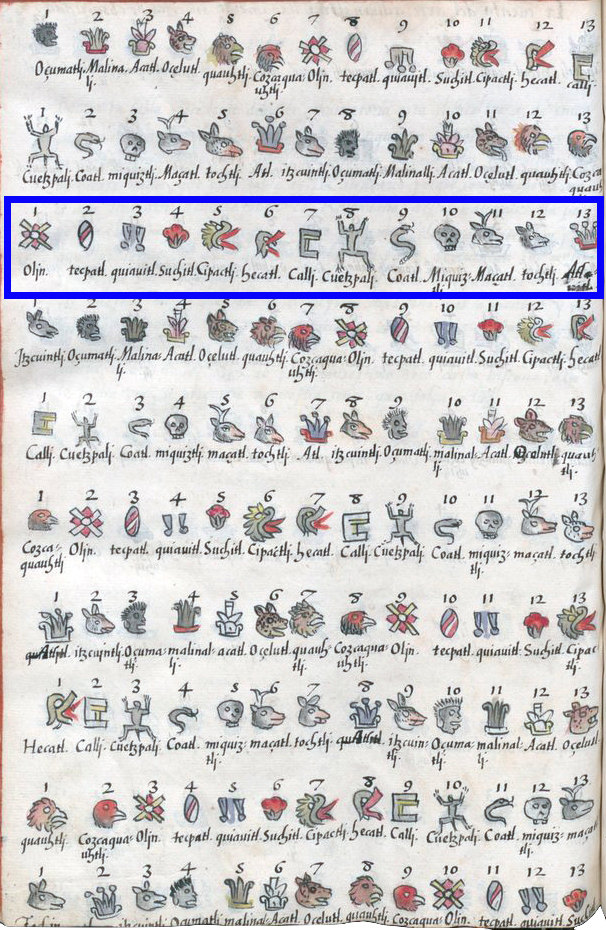

Many Mesoamerican cultures also shared common ways of counting time. Calendars consisted of a system of two different counts that ran simultaneously. The first count tracked a cycle of 260 days (in Nahuatl, the language of the Nahua ethnic group, this was called the tonalpohualli), which was used for divining an individual’s fate (or predicting their future); that fate was itself understood as a portrait of an individual’s character. The other count, closer to our solar year, followed a cycle of 365 days (in Nahuatl, the xiuhpohualli); this calendar tracked the passage of the alternating wet and dry seasons. Calendars were central to Mesoamerican cultures because they were tied to major seasonal cycles, and related to ideas around individuals and their fates.

Works of Mesoamerican art often include references to calendars and time. Taking a closer look at the role of the calendar in different artistic contexts helps us to understand how knowledge about time was represented and utilized in the ancient world.

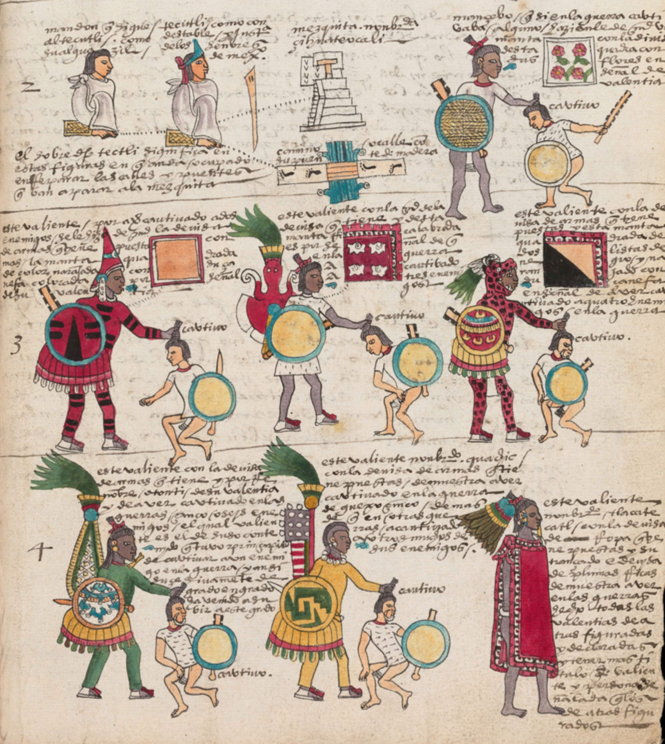

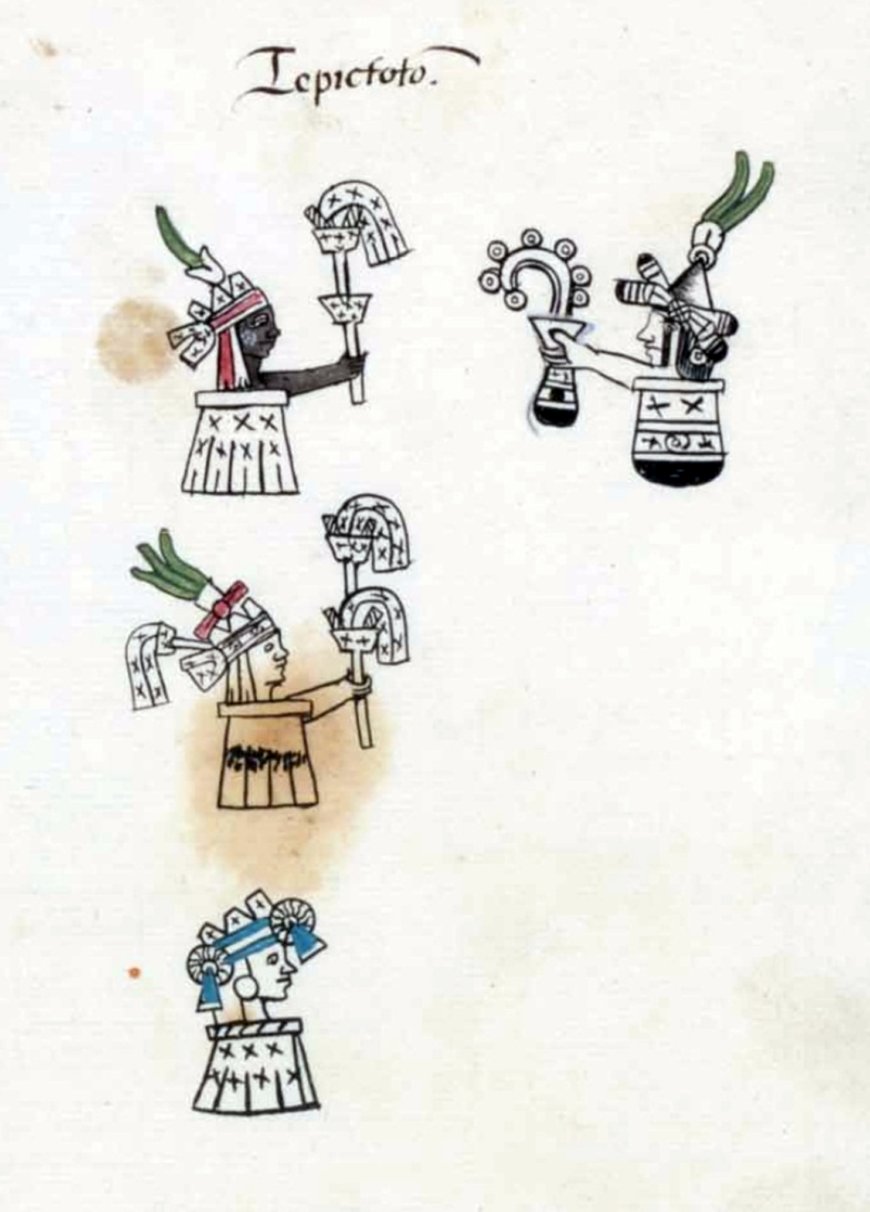

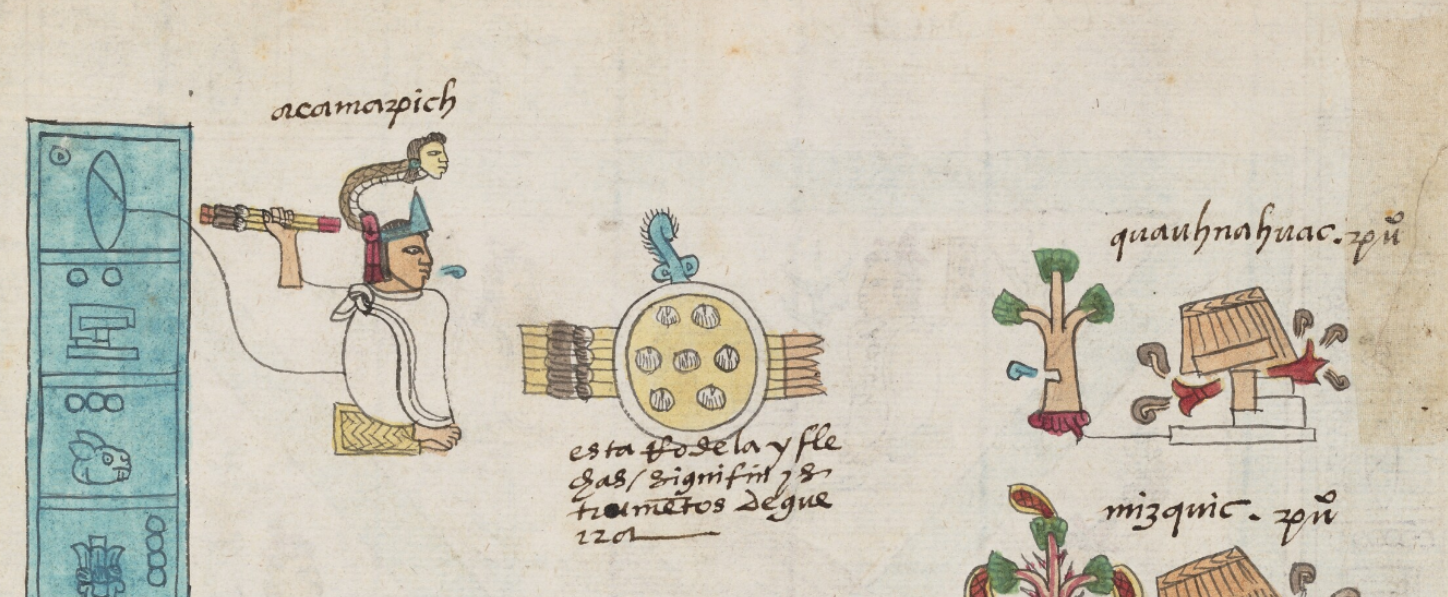

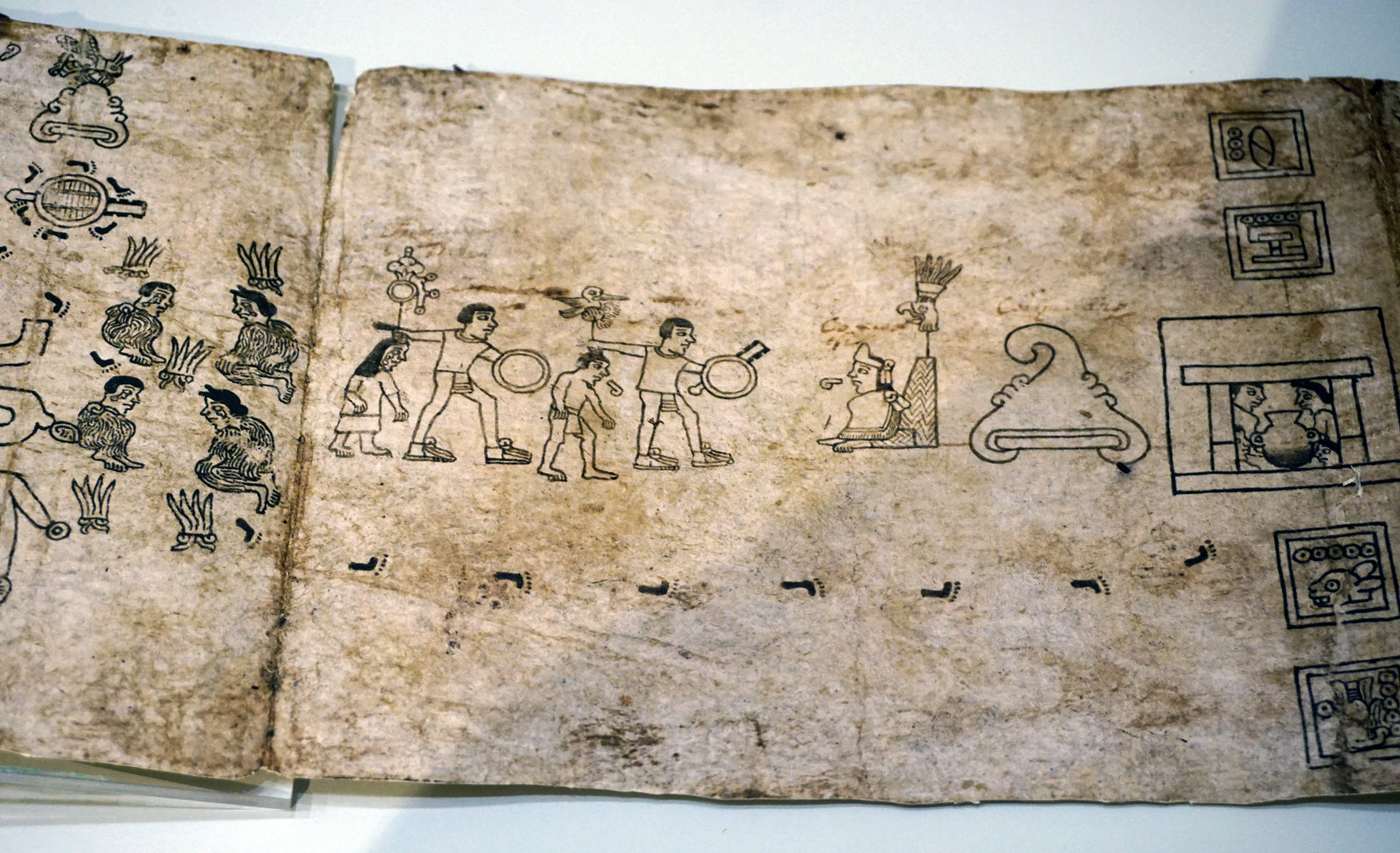

Painting the ritual calendar

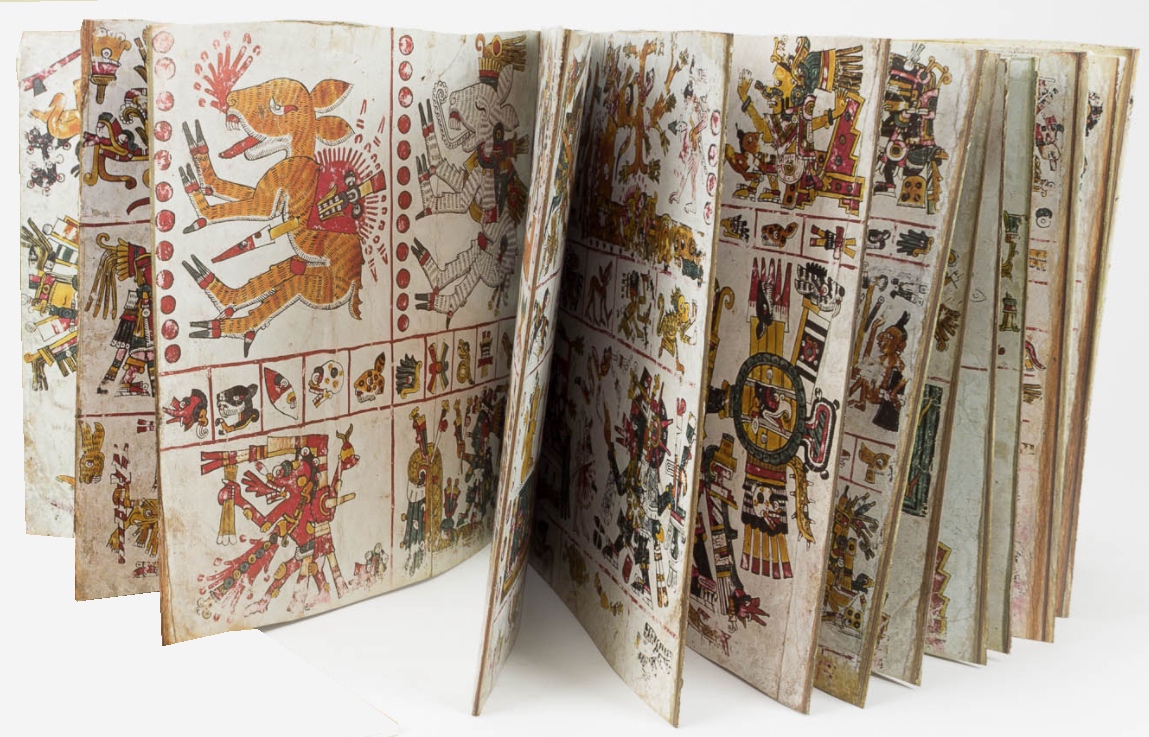

Painted books—known today as codices, or codex in the singular—created both before and after the arrival of Spaniards to Mesoamerica in 1519 give us an idea of how the 260-day ritual count (the count most closely related to divination and prognostication) was represented in Mesoamerican art.

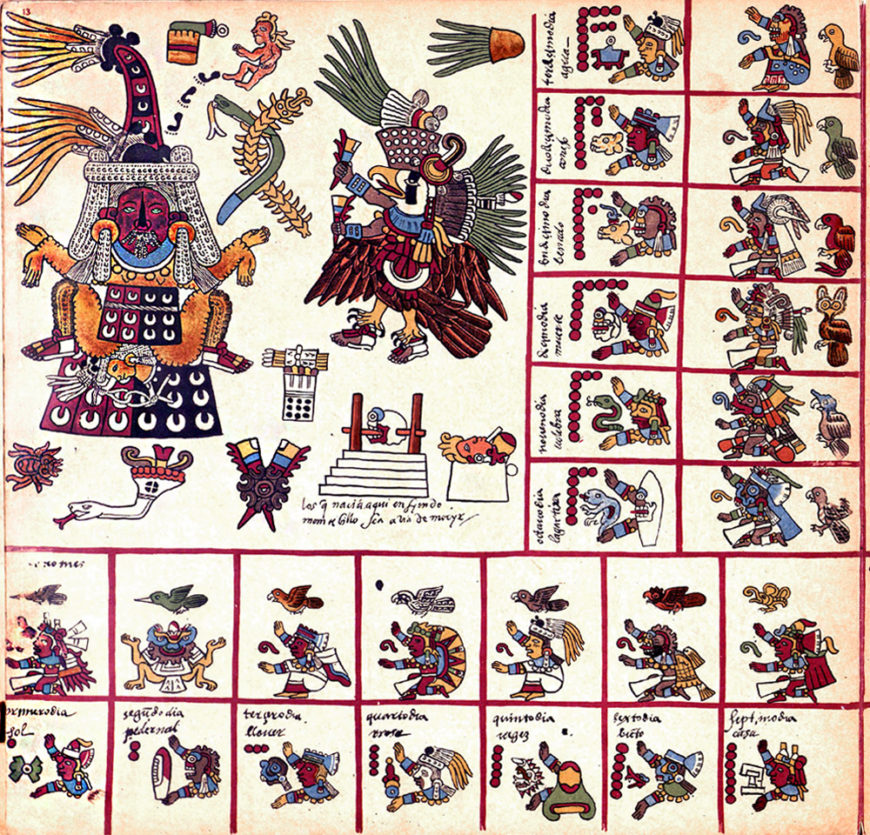

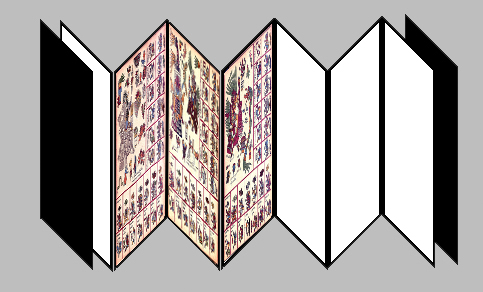

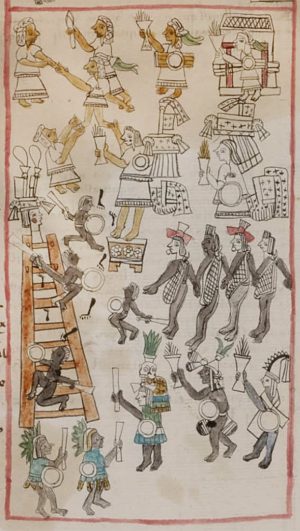

In the first half of the sixteenth century, a painted book (today known as the Codex Borbonicus) was created in Central Mexico using a very long strip of bark paper folded in an accordion-like format. This book was likely similar to the books typical of Mexica (sometimes called Aztec) visual culture, a tradition that flourished in Central Mexico in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

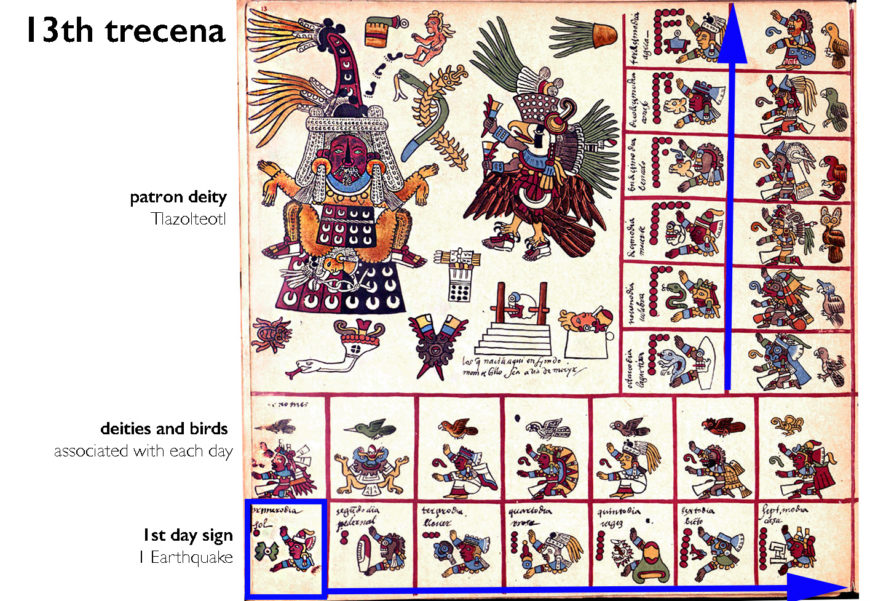

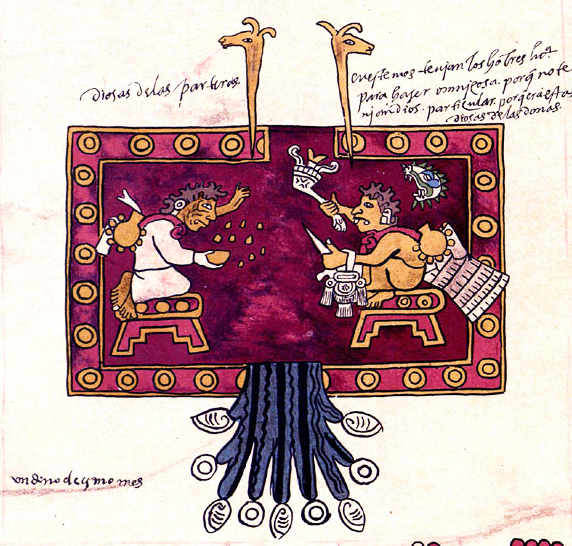

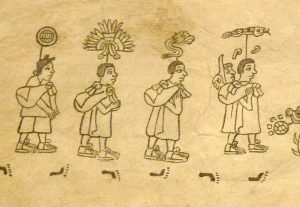

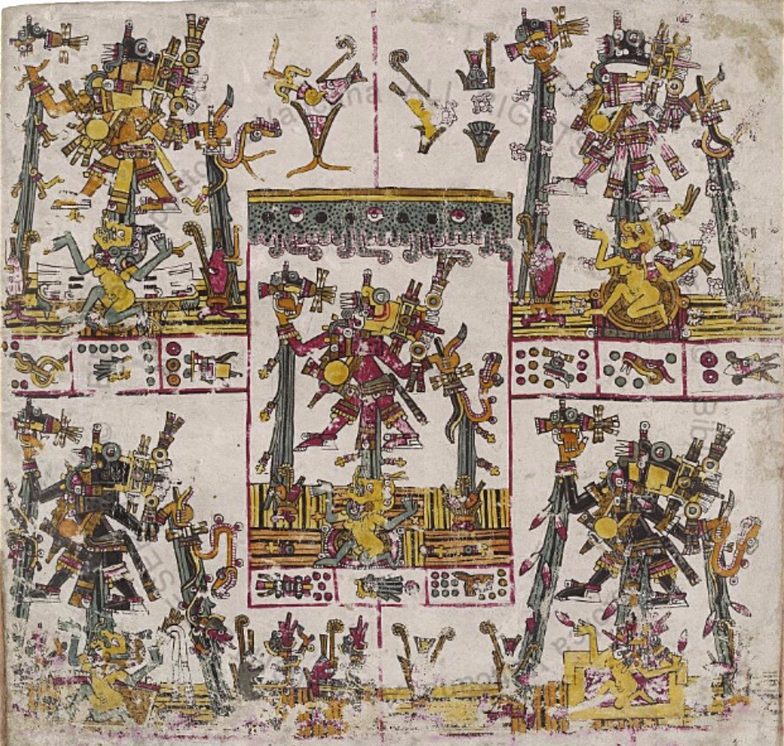

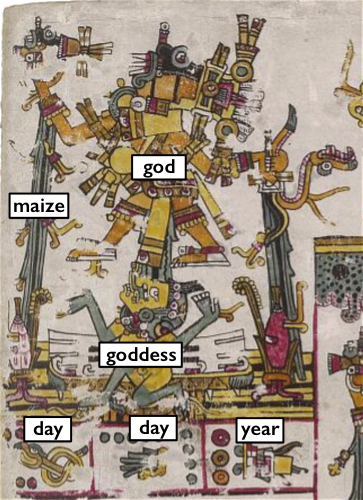

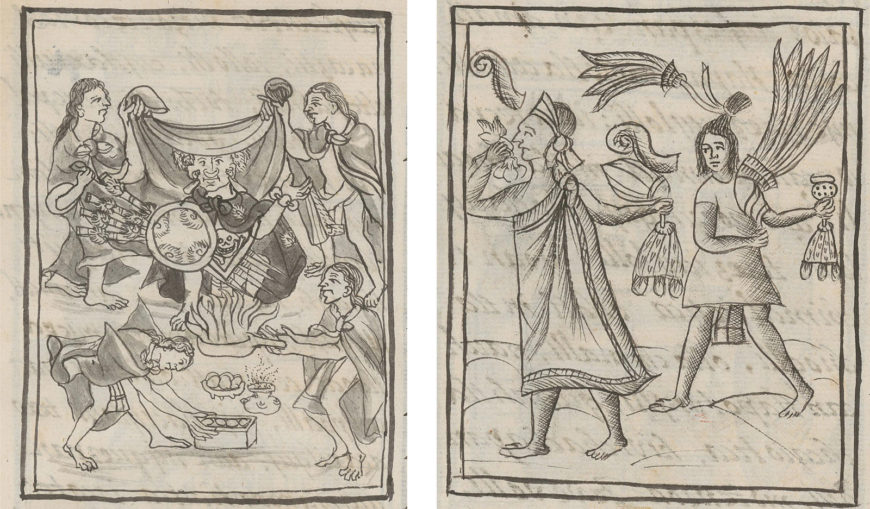

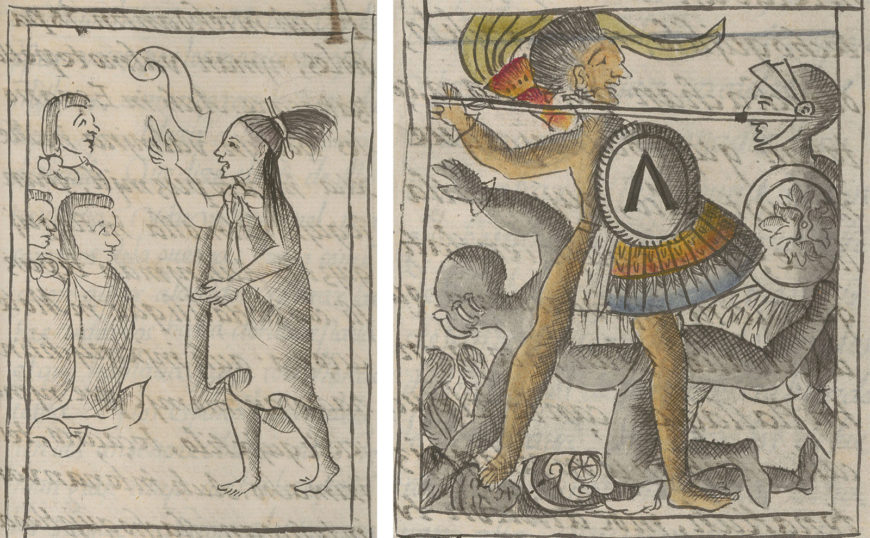

One page from an almanac in the Codex Borbonicus represents a 13-day period (called a trecena), and each trecena had a presiding patron deity. Calendar specialists consulted images like these to interpret whether the individual days that were represented might portend good, evil, or ambiguous fates. The first section of the Codex is dedicated to these 20 months of 13 days that made up the 260-day calendar.

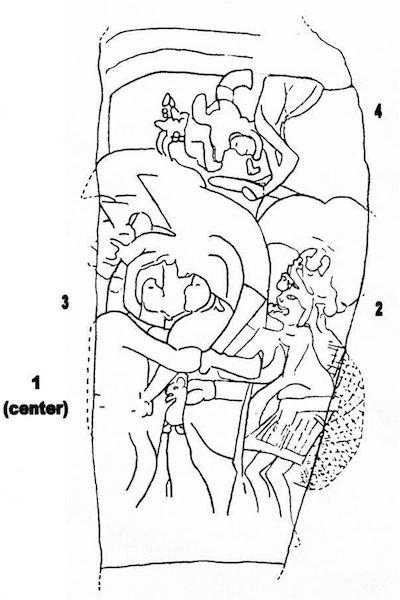

Let us take a close look at the 13th trecena. This complex image consists of two parts, including both the count of days in the ritual calendar and the deities who were associated with those days. In the grids that run along the sides of the page, the artist has painted a sequence of 13 glyphic signs representing each of 13 days; the count starts at the bottom left and ends and the top right. 1 Earthquake is the first day of this period.

Meanwhile, the larger space on the page is a cartouche where we see the gods who are associated with these days. On the left, a frontally oriented female deity (Tlazolteotl) is depicted in the position of giving birth, while the deity on the right is an avian god who holds two perforators for sacrifice. These gods are surrounded by insects like the spider and centipede (creatures associated with night and darkness) and by objects, like an incense burner and perforators.

When a calendar specialist consulted this painting, these images of deities, animals, and objects could be interpreted to understand the fates and characters associated with the set of days referenced in the painting. Each day in the 260-day count was associated with a distinct quality or fate. Some days were believed to be tied to good outcomes and good character; others were ambiguous, and others still predicted evil ends. These destinies also spoke to the identity of people born on those dates. The birthdate of a child was considered in a number of contexts to be intimately tied to their fate, and in some contexts, like in the Mixtec tradition from southern Mexico, individuals were named after their birthdates, speaking to the close tie between the calendar and identity.

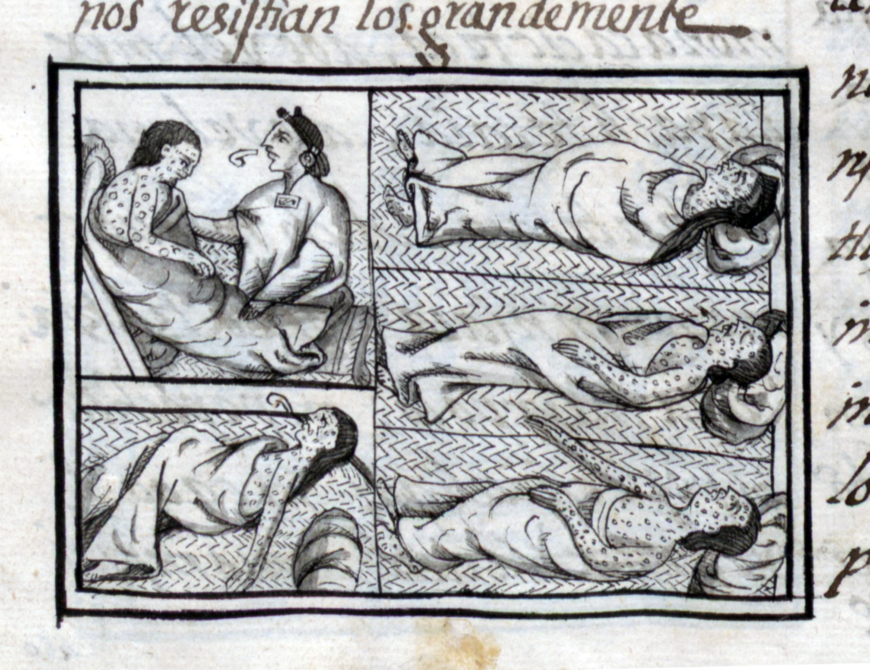

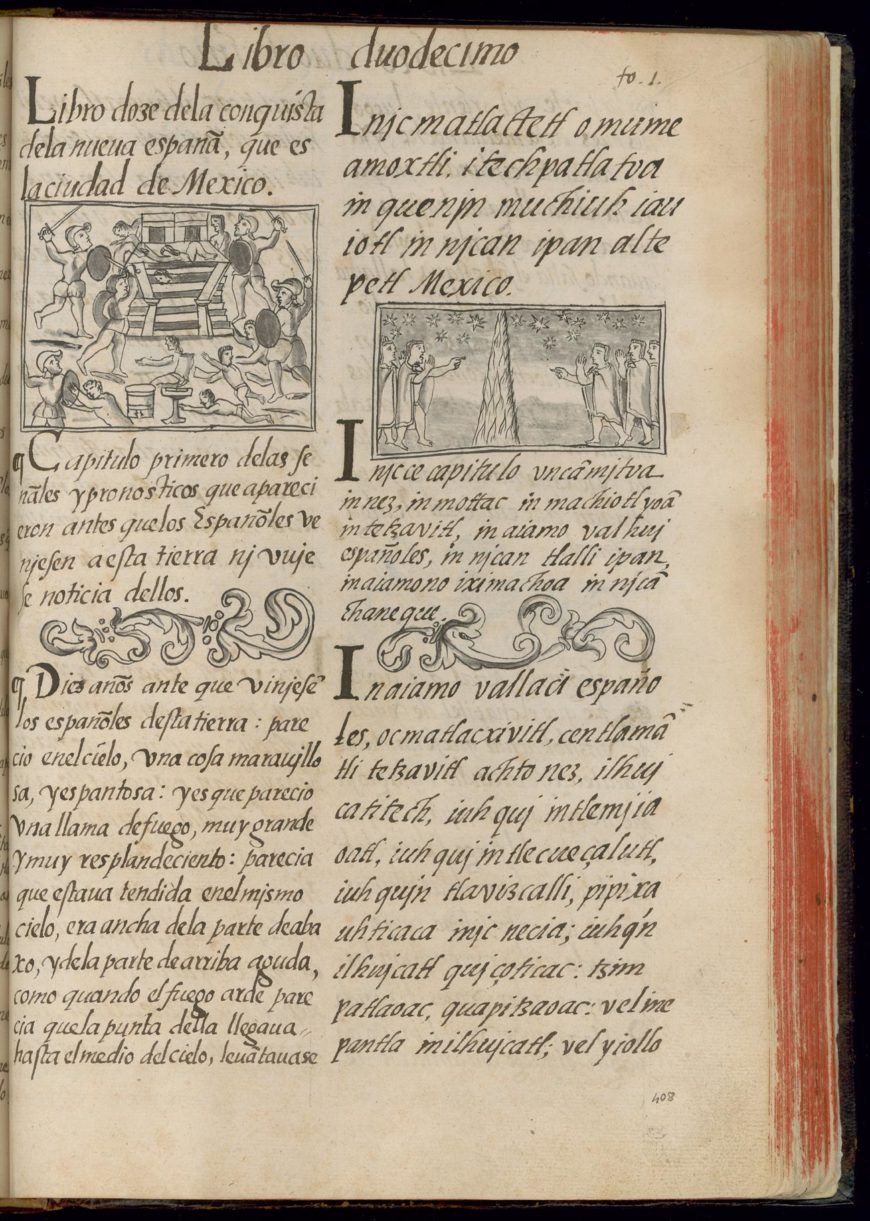

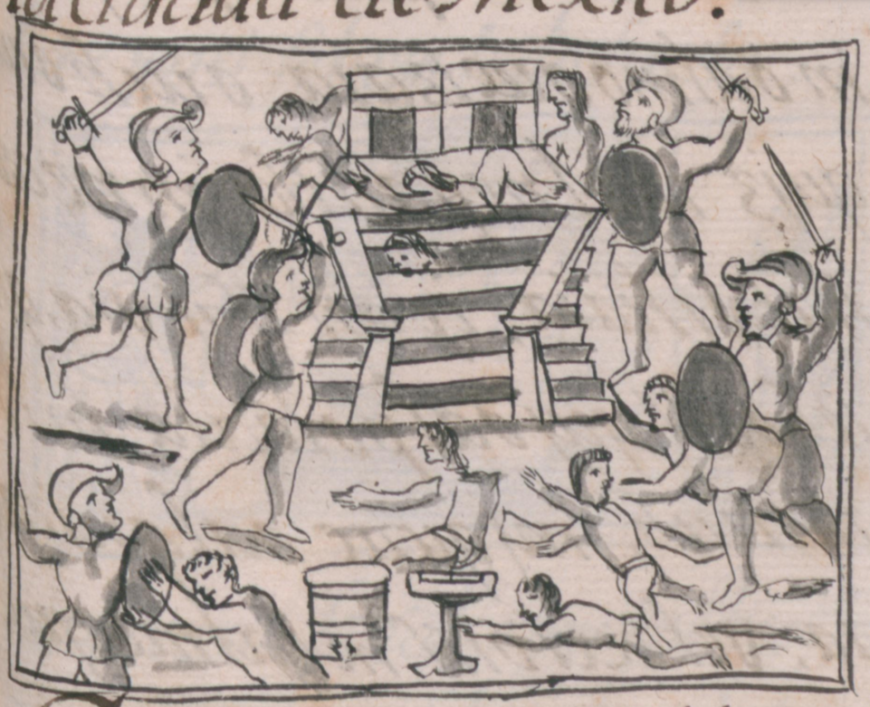

Today, we have some idea of how a painting like this one might have been interpreted in the Aztec world thanks to the texts in a manuscript known as the Florentine Codex. This manuscript was created in the second half of the sixteenth century, after the Spanish Conquest, when the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún asked a number of Nahuatl-speaking Indigenous collaborators to explicate various facets of Nahua thought and history, including their ideas about the calendar. When these collaborators turned to describe the ritual period depicted in the above page of the Codex Borbonicus, they wrote that those born on these days had destinies that were “only half good. He who was then born, man or woman, who did penance well, who took good heed, who was well reared, succeeded and found his [rewards]. But if he did not take good heed, and were not well reared, the opposite resulted. He met misery […]”[1] In this case, the fate of the days in the painting was ambiguous. It might portend either a good or bad fate, depending on the actions taken by the person who was born then.

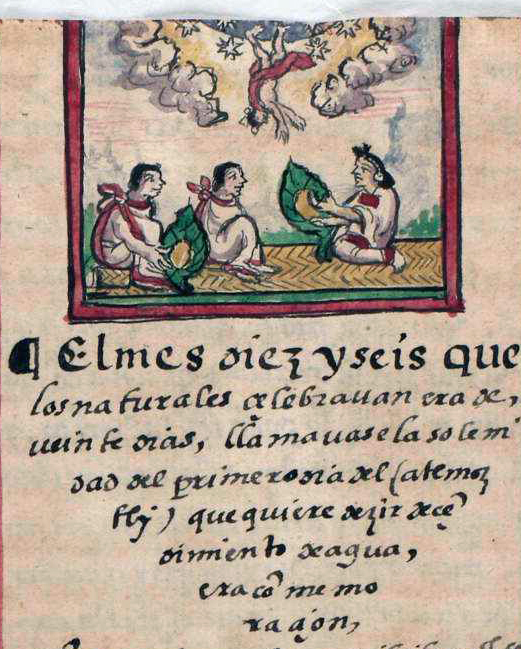

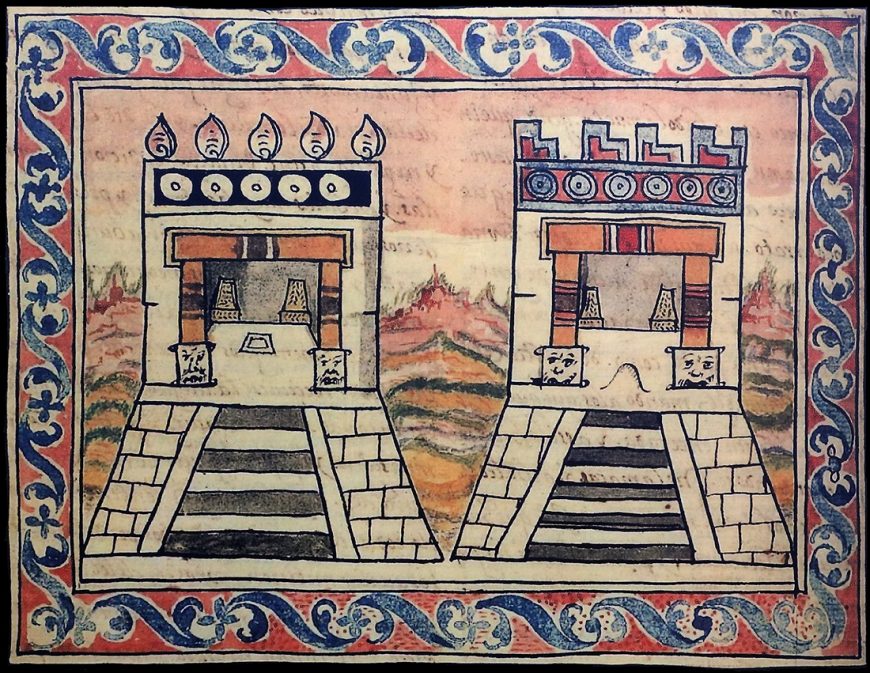

The solar calendar’s festivals

While the 260-day ritual calendar was used for understanding individuals’ fates, the 365-day count tracked the passage of time and the seasons of the solar year. In Aztec culture, the distinctive seasons of the year were times for different activities. During the rainy season, Aztec culture emphasized agricultural fertility and rites to propitiate gods related to water and sustenance. During the subsequent dry season, warfare and the expansion of the empire became major concerns. The 365-day solar calendar was divided into shorter 20-day periods (with 18 months total) when festivals were celebrated that were related to these seasonal concerns. The names of these 20-day periods speak to the character of the seasons: One period is named Toxcatl, “dryness,” and another is called Atlcahualo, “the ceasing of the waters.”

In manuscript paintings made late in the sixteenth century, we find images that depict the festivals that were scheduled according to the 365-day solar calendar. Images of these rites appear in the manuscript known as the Codex Durán. These images were painted by Indigenous artists around Mexico City in the year 1575 and the text was written by the Dominican friar, Diego Durán. One painting shows how an indigenous artist living in the colonial world depicted the ancient festival from the period of Atemoztli, a name that means “the descent of the waters.” In the painting, a group gathers upon a woven mat to eat tamales, the customary food for the celebration of this festival; the descending male figure at the top of the painting may represent the rains. Feasting was an important rite for this festival from the solar calendar; Codex Durán tells us that the tamales that the celebrants eat were considered offerings to ensure good rains and a good harvest. Unlike in the case of the Codex Borbonicus, this painting probably does not follow the format of an ancient book, since pre-Conquest references to the twenty-day festivals do not tend to include ritual scenes combined with important information about the months in the clouds. But it does show us how Indigenous artists imagined one of the festivals surrounding the agricultural cycle from the vantage point of their Colonial context.

The origins of the calendar

Manuscripts like the Codex Borbonicus and the Codex Durán show us how the calendar was visualized in the sixteenth century, but Mesoamerican calendars were in use long before that. We do not know exactly when the counts of the calendar were first adopted in Mesoamerican history, but archaeology tells us that the calendar’s past lies deep in the region’s history. On ancient stone monuments, solar calendar inscriptions appear by the first century B.C.E. in the region of Mexico’s Gulf Coast; in Oaxaca, inscriptions have been found that may date earlier still.

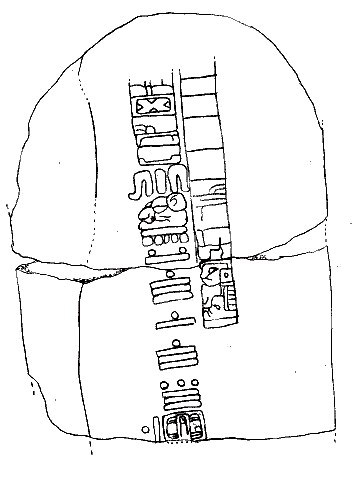

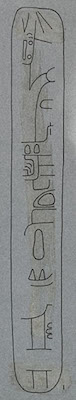

One of the oldest Mesoamerican monuments with a calendrical text is a sculpture from the site of Tres Zapotes, and it includes an inscription that notes the date of 31 B.C.E. Looking closely at its inscription, the left-hand column includes a series of numerals represented as dots above horizontal bars. This part of the text enumerates the number of days that have passed from a commonly held “start” point deep in time; the effect is that the inscription precisely names a single date that we are able to reconstruct today. Thanks to this count, we know exactly which historical moment was named in the inscription, and thanks to this monument, we appreciate the deep historical origins of calendrical monuments in Mesoamerica.

Although archaeology tells part of the story about the origins of the calendar, the Indigenous collaborators who created the Florentine Codex conveyed their ideas about the origins of the calendar. In their telling, the calendar had been invented by deities, including the feathered serpent known as Quetzalcoatl and a divine elderly couple named Oxomoco and Cipactonal; these elders are also named in other Nahuatl-language texts (including the manuscript known as the Anales de Cuauhtitlan). Indigenous peoples living in the colonial period had important beliefs about the sacred origins of the Mesoamerican calendar, beliefs that should be taken into account alongside contemporary archaeology’s story about the origins of the calendar.

Calendrical Inscriptions and Images of Power

Mesoamerican monuments show us that in some cases, calendrical information was deployed in support of images of power. This was the case in both the Maya and the Aztec worlds, where calendrical inscriptions contributed to visualizing the power of rulers.

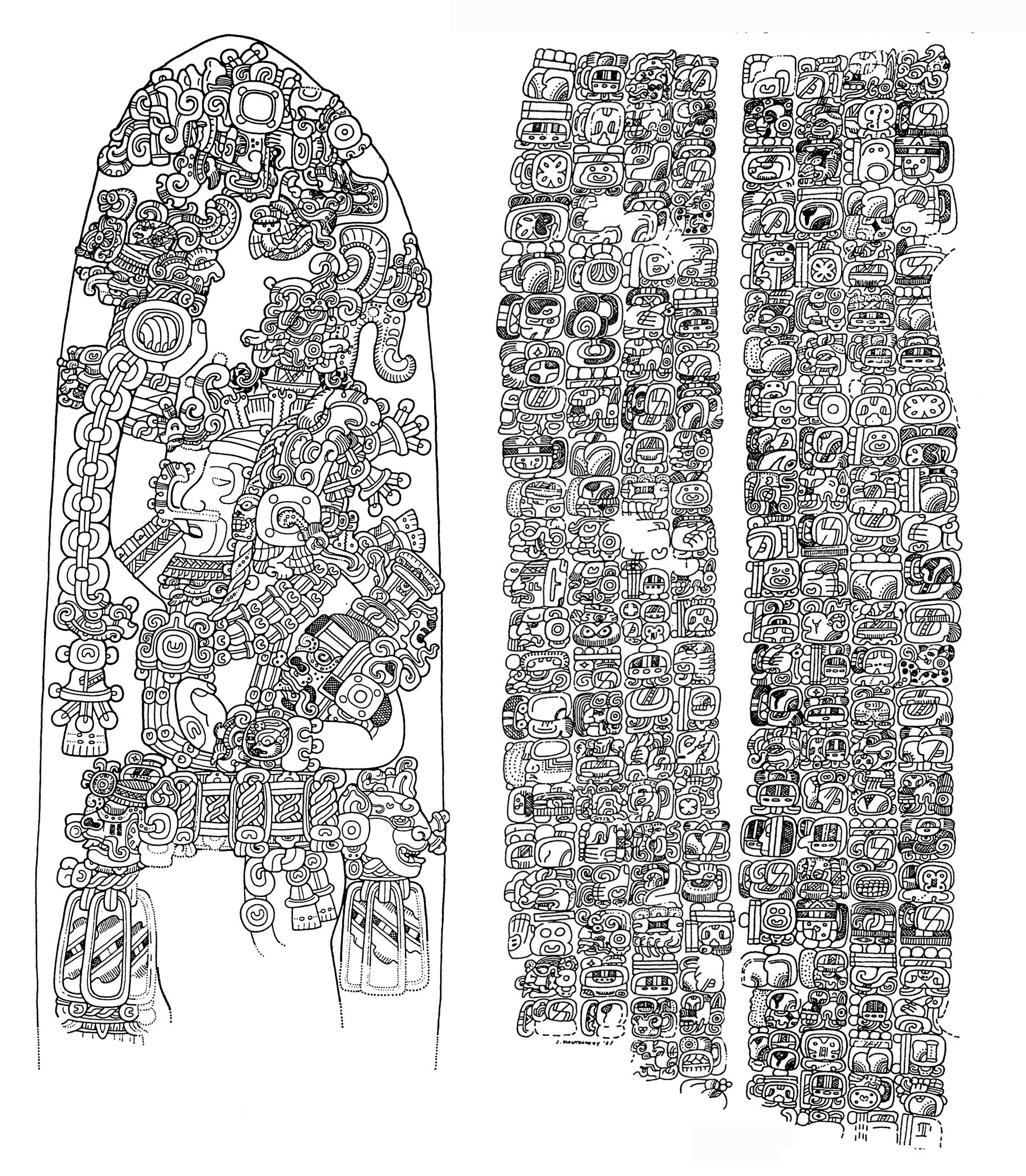

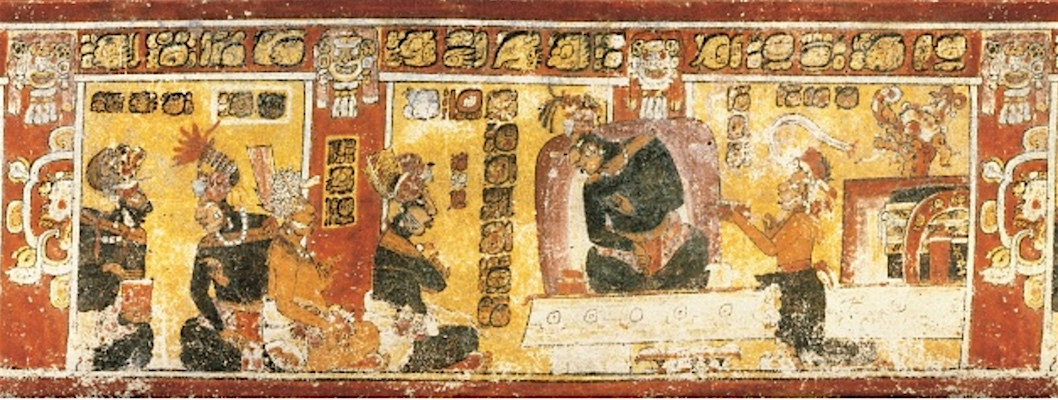

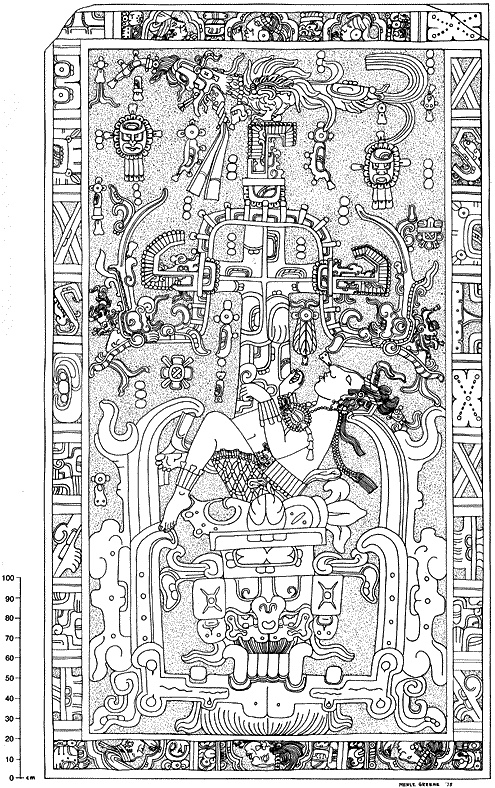

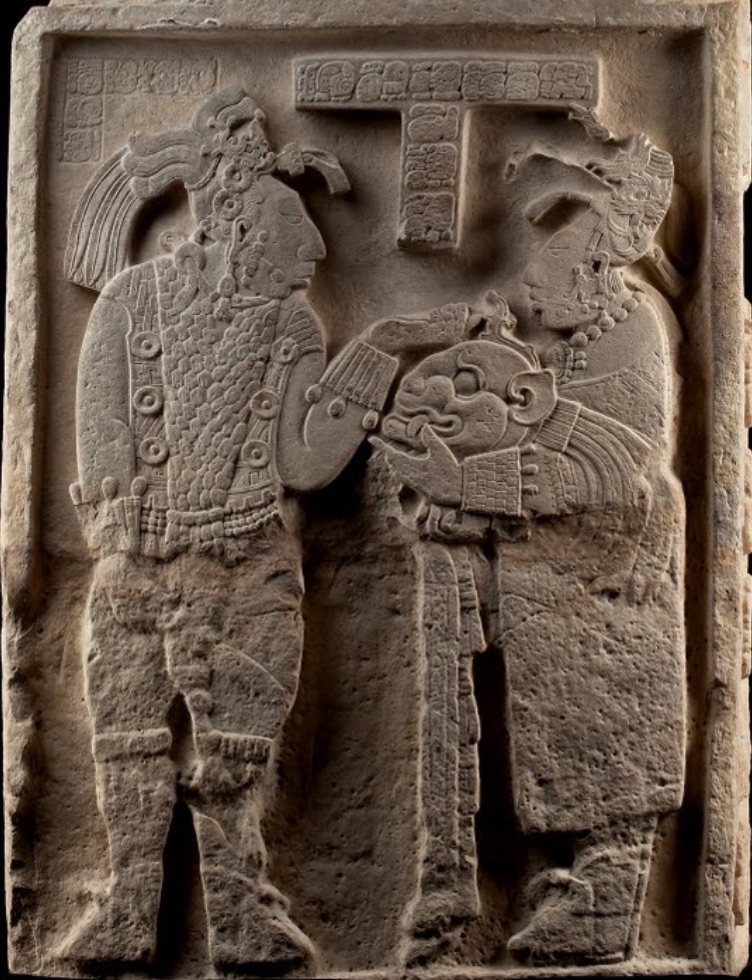

In Classic Maya art, a tradition that flourished between 250 and 900 C.E., freestanding stone sculptures (known as stelae) were a surface where Maya scribes used calendrical inscriptions to record important moments in the lives of kings, such as the dates when they were born or when they ascended to the throne. This was the case on Stela 31 from the site of Tikal in northern Guatemala. Dedicated in the fifth century C.E., the front side of the monument depicts a king from Tikal named Siyah Chan K’awiil II. In the image, he appears covered in elaborate royal finery and accompanied by images referring to his lineage.

On the back of the monument, a long text describes episodes from Tikal’s history, from the moment when a foreign power took up leadership in the city in the previous century through Siyah Chan K’awiil II’s rise to the throne in 435, all the way to the moment when the stela itself was dedicated. Precise calendrical reckoning situated the events that led to Siyah Chan K’awiil II’s reign firmly in historical time and played an important role in constructing the king’s image and authority in this monumental work.

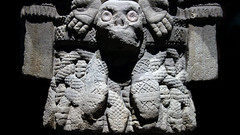

Among the Aztecs, monumental calendrical inscriptions also played an important role in constructing a ruler’s power. The Aztec Dedication Stone represents an important ceremony of royal ritual autosacrifice carried out by a deceased ruler and his successor. At the top of the work, the ruler Ahuitzotl (seen at right) is shown with his royal predecessor Tizoc (left) performing autosacrifice, drawing streams of blood from their ears with sharp perforators. Their sacrificial blood feeds a hungry earth, represented as an upturned, open maw; Aztec religion involved sacrifices in which offerings were made to the earth to ensure that cosmic order was maintained. Below this scene, the sculptor depicted a very large calendrical inscription that dominates the entire composition, associating the ritual with the date 8 Reed (or 1487–1488). With the great visual weight given to this date, this politically potent monument and its concerns around succession and rule shows the importance of graphically foregrounding historical time in an image of royal power in Aztec art. Even so, time is also interestingly manipulated on this monument. Tizoc’s death before Ahuitzotl’s ascension suggests that the time imagined in the ritual scene is likely imaginary; what mattered instead was that the new ruler appear beside his predecessor, emphasizing his continuity with royal power.

Calendar after the Spanish Conquest

In the decades that followed the Spanish Invasion of the Americas, European missionary friars became interested in the Mesoamerican calendar because they sensed that it still held a powerful influence in the communities that they sought to convert to Christianity. In the Codex Durán, Diego Durán wrote that he suspected that an Indigenous town had adopted their patron saint because his feast day fell on an important day on the ancient calendar. [2] Since many of these friars believed that the practice of the ancient calendar was a way of maintaining idolatrous practices, missionaries sought to end the use of the Mesoamerican calendar altogether.

Despite Colonial efforts at extirpation, the calendar continued to constitute an important form of knowledge in some areas of Mesoamerica long after the Colonial period. Among K’iche Maya speakers in the Guatemala highlands, for example, specialists in Mesoamerican calendrical knowledge have continued to interpret and use the calendar in the twenty-first century as an integral part of their social and political milieu. The special place accorded to calendrical knowledge in these communities today speaks to the continued relevance of the Mesoamerican calendar into our own century, as well as the prestige and status accorded to the keepers of this vital form of understanding the world.

Notes:

- Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex, Book 4: p. 85.

- Diego Durán, Book of the Gods and Rites and The Ancient Calendar, trans. Doris Heyden and Fernando Horcasitas [1971], pp. 409–410.

Additional resources:

The Ancient Future: Mesoamerican and Andean Timekeeping at Dumbarton Oaks

Elizabeth Hill Boone, Cycles of Time and Meaning in the Mexican Books of Fate (University of Texas Press, 2007).

Simon Martin and Nikolai Grube, Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens, 2nd ed. (Thames and Hudson, 2008).

Mary Miller, The Art of Mesoamerica from Olmec to Aztec, 6th ed. (2009).

Barbara Tedlock, Time and the Highland Maya, revised ed. (University of New Mexico Press, 1993).

Camelid sacrum in the shape of a canine

Prehistoric art around the globe

When we think about prehistoric art (art before the invention of writing), likely the first thing that comes to mind are the beautiful cave paintings in France and Spain with their naturalistic images of bulls, bison, deer and other animals. But it’s important to note that prehistoric art has been found around the globe—in North and South America, Africa, Asia, and Australia—and that new sites and objects come to light regularly, and many sites are just starting to be explored. Most prehistoric works we have discovered so far date to around 40,000 B.C.E. and after.

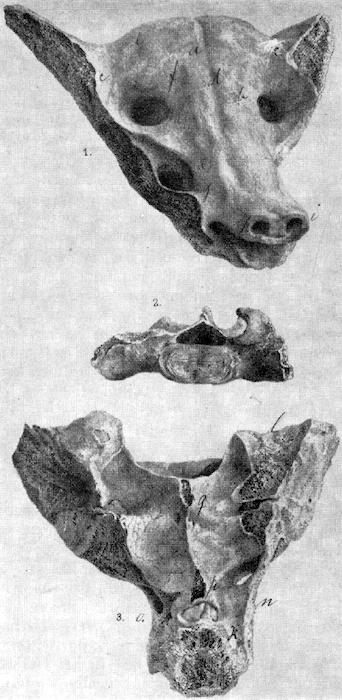

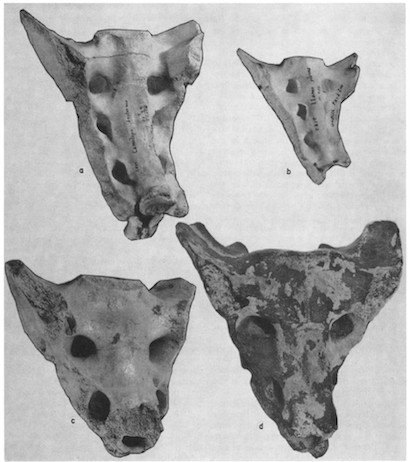

This fascinating and unique prehistoric sculpture of a dog-like animal was discovered accidentally in 1870 in Tequixquiac, Mexico—in the Valley of Mexico (where Mexico City is located). The carving likely dates to sometime between 14,000–7000 B.C.E. An engineer found it at a depth of 12 meters (about 40 feet) when he was working on a drainage project—the Valley of Mexico once held several lakes. The geography and climate of this area was considerably different in the prehistoric era than it is today.

What is a camelid? What is a sacrum?

The sculpture was made from the now fossilized remains of the sacrum of an extinct camelid. A camelid is a member of the Camelidae family—think camels, llamas, and alpacas. The sacrum is the large triangular bone at the base of the spine. Holes were cut into the end of the bone to represent nostrils, and the bone is also engraved (though this is difficult to see in photographs).

Issues

The date of the sculpture is difficult to determine because a stratigraphic analysis was not done at the find spot at the time of discovery. This would have involved a study of the different layers of soil and rock before the object was removed. Another problem is that the object was essentially lost to scholars between 1895 and 1956 (it was in private hands).

In 1882 the sculpture was in the possession of Mariano de la Bárcena, a Mexican geologist and botanist, who wrote the first scholarly article on it. He described the object in this way:

“…the fossil bone contains cuts or carvings that unquestionably were made by the hand of man…the cuts seem to have been made with a sharp instrument and some polish on the edges of the cuts may still be seen…the articular extremity of the last vertebra was utilized perfectly to represent the nose and mouth of the animal.” [1]

Bárcena was convinced of the authenticity of the object, but over the years—due to the lack of scientific evidence from the find spot—other scholars have questioned its age, and whether the object was even made by human hands. One author, in 1923, summarized the issues:

To allow us to state that the sacrum found at Tequixquiac was a definite proof of ancient man in the area the following things must be proven: (1) That the bone was actually a fossil belonging to an extinct species. We cannot doubt this since it has been affirmed by competent geologists and paleontologists. (2) That it was found in a fossiliferous deposit and that it had never been moved since it found its place there. This has not been proved in any convincing manner. (3) That the cuttings of the bone can actually be attributed to the hand of man and that it can never have occurred without human intervention. This has not been proved either. (4) That the carving was made while the species still existed and not in later times when the bone had already become fossilized. [2]

Today, scholars agree that the carving and markings were made by human hands—the two circular spaces that represent the nasal cavities were carefully carved and are perfectly symmetrical and were likely shaped by a sharp instrument. However, the lack of information from the find spot makes precise dating very difficult. It is quite common, in prehistoric art, for the shape of a natural form (like a sacrum) to suggest a subject (dog or pig head) to the carver, and so we should not be surprised that the sculpture still strongly resembles a sacrum.

Interpretation

Because the carving was made in a period before writing had developed, it is likely impossible to know what the sculpture meant to the carver and to his/her culture. One possible way to interpret the object is to look at it through the lens of later Mesoamerican cultures. One anthropologist has pointed out that in Mesoamerica, the sacrum is seen as sacred and that some Mesoamerican Indian languages named this bone with words referring to sacredness and the divine. In English, “sacrum” is derived from Latin: os sacrum, meaning “sacred bone.” The sacrum is also—perhaps significantly for its meaning—located near the reproductive organs.

“Language and iconographic evidence strongly suggests that the sacrum bone was an important bone indeed in Mesoamerica, relating to sacredness, to resurrection, and to fire. The importance attached to this bone and its immediate neighbors is not limited to Mesoamerica. From ancient Egypt to ancient India and elsewhere, there is abundant evidence that the bones at the base of the spine, including especially the sacrum, were seen as sacred.” [3]

As appealing as this interpretation is (and the argument the author makes is quite convincing), it is wise to be wary of connecting cultures across such vast geographic distances (though of course there are some aspects of our shared humanity that may be common across cultures). At this point in time, we have no direct evidence to support this interpretation, and so we can not be certain of this object’s original meaning for either the artist, or the people that produced it.

[1] As quoted in Luis Aveleyra Arroyo de Anda, “The Pleistocene Carved Bone from Tequixquiac, Mexico: A Reappraisal,” American Antiquity, vol. 30, (January 1965), p. 264.

[2] As quoted in Luis Aveleyra Arroyo de Anda, “The Pleistocene Carved Bone from Tequixquiac, Mexico: A Reappraisal,” American Antiquity, vol. 30, (January 1965)

[3] Brian Stross, “The Mesoamerican Sacrum Bone: Doorway to the otherworld,” FAMSI Journal of the Ancient Americas (2007) pp.1-54.

Additional resources:

Luis Aveleyra Arroyo de Anda, “The Pleistocene Carved Bone from Tequixquiac, Mexico: A Reappraisal,” American Antiquity, vol. 30, (January 1965), pp. 261-77 (available online).

Paul G. Bahn, “Pleistocene Images outside of Europe,” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 57, part 1 (1991), pp. 91-102.

Brian Stross, “The Mesoamerican Sacrum Bone: Doorway to the otherworld,” FAMSI Journal of the Ancient Americas (2007), pp.1-54 (pdf available online).

Tlatilco

Tlatilco Figurines

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Tlatilco figurines, c. 1200–600 B.C.E., ceramic, Tlatilco, Mesoamerica (present-day Mexico) (includes examples from the National Museum of Anthropology as well as the Female Figure at the Princeton University Art Museum)

We don’t know what the people here called themselves. Tlatilco, meaning “place of hidden things,” is a Nahuatl word, given to this “culture” later. Around 2000 B.C.E., maize, squash and other crops were domesticated, which allowed people to settle in villages. The settlement of Tlatilco was located close to a lake, and fishing and the hunting of birds became important food sources.

Archaeologists have found more than 340 burials at Tlatilco, with many more destroyed in the first half of the 20th century.

Intimate and lively

Tlatilco figurines are wonderful small ceramic figures, often of women, found in Central Mexico. This is the region of the later and much better-known Aztec empire, but the people of Tlatilco flourished 2,000-3,000 years before the Aztec came to power in this Valley. Although Tlatilco was already settled by the Early Preclassic period (c. 1800-1200 B.C.E.), most scholars believe that the many figurines date from the Middle Preclassic period, or about 1200-400 B.C.E. Their intimate, lively poses and elaborate hairstyles are indicative of the already sophisticated artistic tradition. This is remarkable given the early dates. Ceramic figures of any sort were widespread for only a few centuries before the appearance of Tlatilco figurines.

Appearance

The Tlatilco figurine at the Princeton University Art Museum has several traits that directly relate to many other Tlatilco female figures: the emphasis on the wide hips, the spherical upper thighs, and the pinched waist. Many Tlatilco figurines also show no interest in the hands or feet, as we see here. Artists treated hairstyles with great care and detail, however, suggesting that it was hair and its styling was important for the people of Tlatilco, as it was for many peoples of this region. This figurine not only shows an elaborate hairstyle, but shows it for two connected heads (on the single body). We have other two-headed female figures from Tlatilco, but they are rare when compared with the figures that show a single head. It is very difficult to know exactly why the artist depicted a bicephalic (two-headed) figure (as opposed to the normal single head), as we have no documents or other aids that would help us define the meaning. It may be that the people of Tlatilco were interested in expressing an idea of duality, as many scholars have argued.

The makers of Tlatilco figurines lived in a large farming villages near the great inland lake in the center of the basin of Mexico. Modern Mexico City sits on top of the remains of the village, making archaeological work difficult. We don’t know what the village would have looked beyond the basic shape of the common house—a mud and reed hut that was the favored house design of many early peoples of Mexico. We do know that most of the inhabitants made their living by growing maize (corn) and taking advantage of the rich lake resources nearby. Some of the motifs found on other Tlatilco ceramics, such as ducks and fish, would have come directly from their lakeside surroundings.

Male figures are rare

Tlatilco artists rarely depicted males, but when they did the males were often wearing costumes and even masks. Masks were very rare on female figures; most female figures stress hairstyle and/or body paint. Thus the male figures seem to be valued more for their ritual roles as priests or other religious specialists, while the religious role of the females is less clear but was very likely present.

How they were found

In the first half of the 20th century, a great number of graves were found by brick-makers mining clay in the area. These brick-makers would often sell the objects—many of them figurines—that came out of these graves to interested collectors. Later archaeologists were able to dig a number of complete burials, and they too found a wealth of objects buried with the dead. The objects that were found in largest quantities—and that enchanted many collectors and scholars of ancient Mexico—were the ceramic figurines.

Craftsmanship

Unlike some later Mexican figurines, those of Tlatilco were made exclusively by hand, without relying on molds. It is important to think, then, about the consistent mastery shown by the artists of many of these figurines. The main forms were created through pinching the clay and then shaping it by hand, while some of the details were created by a sharp instrument cutting linear motifs onto the wet clay. The forms of the body were depicted in a specific proportion that, while non-naturalistic, was striking and effective. The artist was given a very small space (most figures are less than 15 cm high) in which to create elaborate hairstyles. Even for today’s viewer, the details in this area are endlessly fascinating. The pieces have a nice finish, and the paint that must indicate body decoration was firmly applied (when it is preserved, as in the two-headed figure above). Many scholars doubt that there were already full-time artists in such farming villages, but it is certain that the skills necessary to function as an artist in the tradition were passed down and mastered over generations.

Additional resources:

Ceramics from Tlatilco (including the two headed figurine at the Princeton Art Museum)

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Olmec

The Olmecs flourished on the Gulf Coast, creating works in stone and jade that had a profound influence on later cultures.

c. 1200 - 400 B.C.E.

Kunz Axe (Olmec)

by DR. REX KOONTZ and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Additional resources:

Olmec art on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (by Dr. James Doyle)

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Offering #4, La Venta

by DR. BILLIE FOLLENSBEE

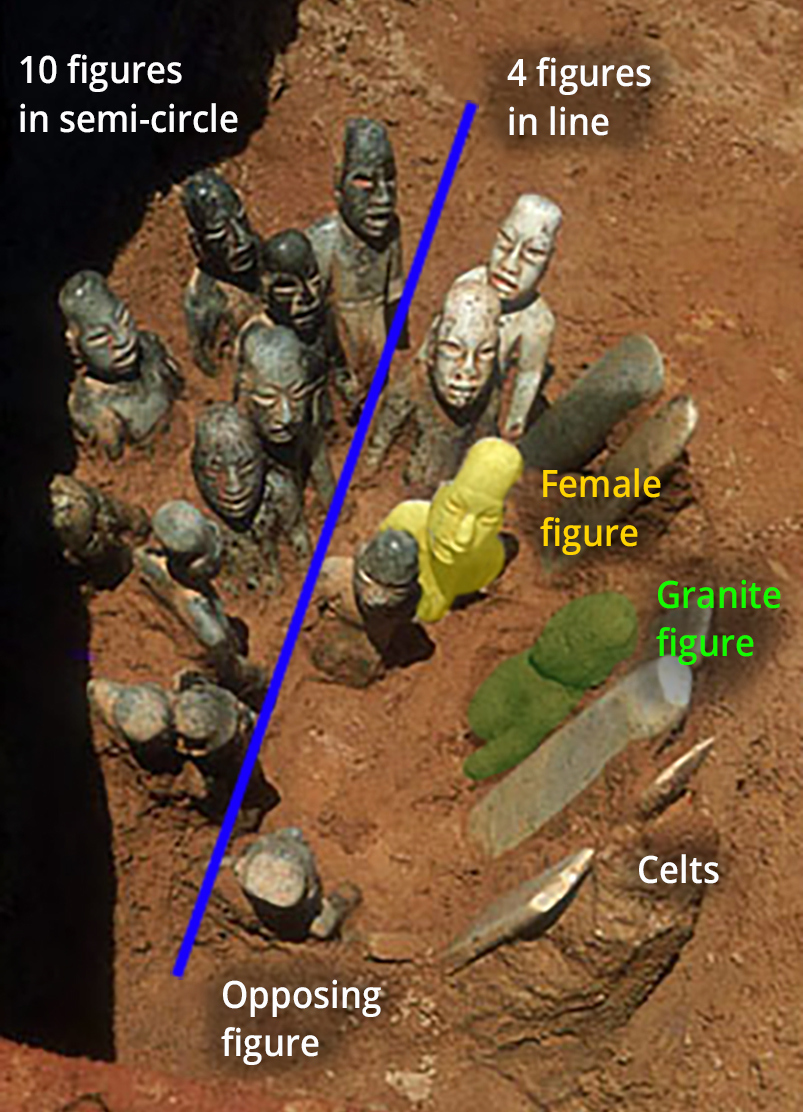

Offering #4 from La Venta is perhaps the most dramatic assemblage of Olmec small stone figures yet discovered. As found in situ (in the original place and arrangement that the Olmec people left them), the group consisted of seventeen stone figurines arranged in front of a flat row of six slender jade celts, all securely set upright in a base of sand. Only fragments remained of one figure, but the surviving sculptures illustrate a striking, enigmatic scene: A single figure stands with its back to the celts (see granite figure in diagram left), while four figures appear to process in front of this figure, apparently walking toward a fifth figure that faces them (see opposing figure in diagram). The ten remaining figures gather in a close semi-circle, facing the celts as if watching the procession.

Material and style

The material and style of this group of figures represents the artistic culmination of Olmec small stone carving. After focusing most of their efforts on making large stone sculptures during the Early Formative period (2000–1000 B.C.E.), the Olmec of the Middle Formative period began to produce these much smaller, portable stone sculptures as well.

The stone used to produce many of these sculptures also indicates the importance of Offering #4. While one unusual figure in Offering #4 is made of now-rough, eroded granite, and the fragmentary figure (likely its companion, also standing with back to the celts—not shown) was badly decomposed schistose—both victims of La Venta’s highly acidic soils—the remaining 21 sculptures are made of greenstone, a material that Mesoamericans valued above all others. Greenstone includes all green and bluish-green stones, with the most highly coveted form being jadeite, the American form of jade. Thirteen of the figures are composed of greenish serpentine, while two figures and all six of the celts are jade.

Figure \(\PageIndex{60}\): Several Offering #4 figures (granite figure first on the left; female figure third from the left), photo: 1955 (R.F. Heizer collection, National Anthropological Archives, catalogue ID: heizer_0114)

Figure \(\PageIndex{60}\): Several Offering #4 figures (granite figure first on the left; female figure third from the left), photo: 1955 (R.F. Heizer collection, National Anthropological Archives, catalogue ID: heizer_0114)

The figures all take the typically Olmec style often referred to as the “baby-face,” with an elongated head and a face with a down-turned mouth, puffy almond-shaped eyes, a triangular nose with drilled nostrils, and long, narrow ears with drilled holes in the lobes. The figures also all have nearly flat, slender bodies and take the classic pose of standing baby-face figures, with slightly bent knees and legs apart in a V, and arms held stiffly out to each side, with slightly bent elbows.

The six celts, meanwhile, are especially thin and narrow, clearly decorative objects rather than utilitarian axes or adzes.

Repurposing and recycling

Taken all together, the figures and celts of Offering #4 are similar in style, but their individualized features reveal that no single artist or workshop produced all of the sculptures; in other words, the Olmec did not create these sculptures as one group, expressly for this offering, but assembled this scene by repurposing and even recycling other small stone sculptures.

While the figures all take the classic baby-face style, they vary in color and details. Their heights and proportions vary, as do specific facial features such as the mouths; some have open, empty mouths, while others display a bare gum ridge, and still others have detailed teeth. Several figures were also already worn and broken, with missing hands, arms, or feet, when this offering was assembled. Other figures show evidence of reworking; for example, while some have deeply carved and well-modeled chest features and loincloths, others have only rudimentary, incised chests and loincloths that contrast with the original fine carving of the figure. The drilled ear holes, open poses, and elongated heads also strongly suggest that the figures may once have worn ornaments, clothing, headdresses, or possibly even wigs—and their dress could have changed for different occasions.

The six celts, meanwhile, may have assumed their final, thin forms for the scene portrayed in Offering #4, but four of the celts illustrate the remains of incised imagery on one side, revealing that they had previous incarnations as parts of other objects. Placing a mirror next to one celt shows that it once formed half of a jade object incised with the image of an Olmec supernatural; another celt illustrates incomplete geometric shapes. The last two incised celts reveal their secrets when placed side-by-side; together, they illustrate the image of a richly attired, prone man with his head facing forward—a well-known Olmec image called “the flying Olmec”—and show that the two celts were once part of a larger object.

None of this is surprising, however, as scholars have established that the Olmec reworked and re-carved their large stone sculptures, sometimes completely transforming them into other sculptures, and that the Olmec arranged and re-arranged large stone sculptures into different historical or mythological scenes. La Venta Offering #4 offers strong evidence that the Olmec likewise used and re-used figurines and celts to create scenes on a smaller scale

Possible meanings

The meaning of the scene portrayed in Offering #4 has long been a mystery, although most scholars concur that it represents some sort of important mythological or historic event. Some have speculated that the scene might portray a group of priests involved in an important ritual or procession to honor a visiting dignitary, or that perhaps it is a gathering to prepare a human sacrifice. Recent research has established that the row of celts forming the backdrop of the scene likely represent stelae—upright standing stones that are often covered in relief sculpture—and that the scene therefore takes place at an important site. Other studies have revealed that two of the figures–the second figure in the procession and one figure in the on-looking crowd—have chest and groin features suggesting that they are female.

The female in the procession is one of the two jade figures, and it is the most stylized figure of Offering #4, with an especially large head and a very light blue-green color. The other jade figure is the figure facing the procession—a larger, finely carved male figure of bright green jadeite that wears a prominent incised loincloth. If the jade material was particularly significant, these two figures might be interpreted as the main actors of the event, with the remaining figures of the procession perhaps acting as attendants, and the granite figure facing the crowd (and possibly the now-disintegrated schistose figure) acting as priest or important witness. If so, Offering #4 might represent a meeting of two dignitaries, the establishing of an important alliance, or, if the jade figure in the procession is in fact female, even the marriage of two people of high status—all types of scenes that also appear to be recorded in Olmec relief sculpture (see below).

An important offering

Whatever the meaning behind Offering #4, the Olmec clearly assembled the objects into this scene as an important offering, since before the figures were placed into position, they were covered in red cinnabar and hematite pigment—a treatment reserved for high-status offerings and burials. The Olmec also completely buried the scene in specially cleaned, pure white sand immediately after they placed the figures and celts into position, then covered the mound of sand with clean fill, and finally constructed a large platform on top.

Offering #4 and the event that it commemorates apparently lingered long in Olmec collective memory as well. According to the original excavation reports, about 100 years after the original deposit, a later generation dug a small, precisely oriented oval pit down through four layers of platform flooring, through the fill, and into the white sand of the deposit. However, they dug just down to the tops of the celts and the figurines’ heads, as if to check and verify that the scene was undisturbed—and then immediately reburied them once again.

Additional resources:

Olmec art on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (by Dr. James Doyle)

Phillip Drucker,, Robert F. Heizer, and Robert Squier. Excavations at La Venta (Tabasco. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 170. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.,1959), pp. 152-161 and plates 30-36.

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

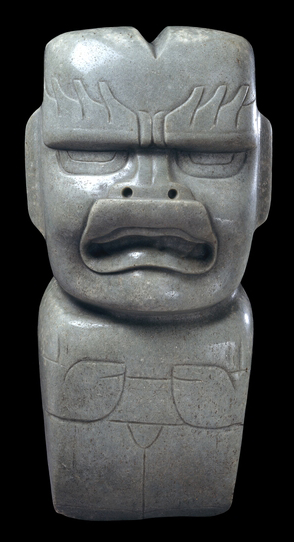

Olmec Jade

Jade votive axe

The Olmec fashioned votive axes in the form of figures carved from jade, jadeite, serpentine and other greenstones. The figures have a large head and a small, stocky body that narrows into a blade shape. They combine features of a human and other animals, such as jaguar, eagle or toad. The mouth is slightly opened, with a flaring upper lip and the corners turned down. The flaming eyebrows seen on this example are also a recurrent feature, and have been interpreted as a representation of the crest of the harpy eagle.

Most axes, including this one, have a pronounced cleft in the middle of the head. This cleft has been interpreted by scholars variously as the open fontanelle (soft spot) on the crown of newborn babies, the deep groove in the skull of male jaguars, or that found on the head of certain species of toads. In some instances vegetation sprouts out of some of them. These combinations of human and animal traits and representations of supernatural beings are common in Olmec art.

Jade perforator

Perforators were used in self-sacrifice rites, which involved drawing blood from several parts of the body. Some representations of Olmec rulers show them holding bloodletters and/or scepters as part of their elaborate ritual costume.

Bloodletting was performed by the ruler to ensure the fertility of the land and the well-being of the community. It was also a means of communication with the ancestors and was vital to sustain the gods and the world. These rituals were common throughout Mesoamerica.Olmec jade perforators are often found in graves as part of the funerary offerings. Bloodletting implements were also fashioned out of bone, flint, greenstones, stingray spines and shark teeth. They vary in form and symbolism. Handles can be plain, incised with a variety of symbols associated to certain deities, or carved into the shape of supernatural beings. The blades, ending in a sharp point, are sometimes shaped into the beaks of certain birds, such as the hummingbird, or into a stingray tail.

This large perforator was probably not used as a bloodletting instrument; it might have been placed in a grave as an offering, or may have served a symbolic function.

Jade pectoral

This pectoral (chest ornament), broken on both sides, was carved by an Olmec artist and reused by the Maya, as shown by the two Maya glyphs on the left side. The edges framing the head at the top and bottom indicate that it could also have been part of a larger pectoral.

Jade objects in Olmec style have been found throughout Mesoamerica and as far south as Costa Rica. Those found in areas of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras, are decorated with different motifs and shapes from those found in the Olmec heartland, centered in present-day Southern Veracruz and Tabasco.

Although contacts between the Maya area and the Olmec heartland seem to have been limited, jade objects in Olmec style appear in Maya deposits dated to the Middle Preclassic (about 1000-400 B.C.E.). Its presence was probably the result of contact between the two areas or with areas that shared the same cultural traditions and similar imagery. Objects found in later deposits, for example at the Cenote of Sacrifice, in Chichen Itza, an Early Postclassic site (900-1200 C.E.), would have been reused over generations or found in earlier graves.

This portrait is a remarkable example of the finest Olmec lapidary art. It was designed to be worn as a pectoral and the pair of Maya name glyphs inscribed on one flange indicate that it was later reused by a Maya lord as a treasured heirloom. Unusually the glyphs are drawn backward so that they face the Olmec portrait, hinting at the power of the object as a symbol of ancestral, dynastic authority. The depressed iris of the eyes and the pierced nose probably bore additional shell work and ornament.

Suggested readings:

Michael Coe, The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership (Princeton, N.J., Art Museum, Princeton University in association with Harry N. Abrams, 1996).

E. Benson (ed.), The Olmec and their neighbors (Washington, DC, Dumbarton Oaks, 1981).

E. Benson and B. de la Fuente (eds.), Olmec art of ancient Mexico (Washington, National Gallery of Art, 1996).

C. McEwan, Ancient Mexico in the British (London, The British Museum Press, 1994).

© Trustees of the British Museum

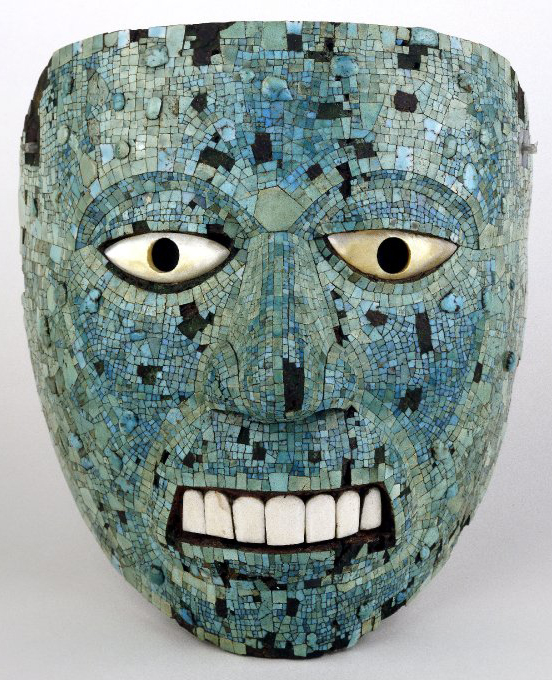

Olmec mask

by DR. LAUREN KILROY-EWBANK and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

The Olmecs are known as “rubber people,” a name given to the peoples of the Gulf Coast after the Spanish Conquest. We don’t know what they called themselves.

Items buried in offerings included ceramic vessels, stone sculptures, obsidian blades, seashells, greenstone, and objects gathered from earlier locales (like Olmec sites and the city of Teotihuacan). Jadeite was quarried in the Sierra de las Minas in Guatemala, and was imported to the Gulf Coast of Mexico. Items acquired via trade or tribute (by the Aztecs) included feathers, obsidian, jadeite, cotton, cacao, and turquoise.

Additional resources:

Olmec art on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (by Dr. James Doyle)

SmartHistory images for teaching and learning:

Olmec mask at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

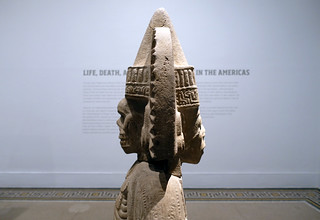

by THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART