10.10: American art to World War II

- Page ID

- 66962

American art to World War II

From the avant-garde to the everyday, American artists responded to rapid changes before WWII.

c. 1890 - 1945

American Impressionism

Metcalf, Havana Harbor

by DR. KATHERINE BOURGUIGNON, TERRA FOUNDATION OF AMERICAN ART and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Willard Metcalf, Havana Harbor, 1902, oil on canvas, 46.5 x 66.4 cm (Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1992.49), a Seeing America video. Dr. Katherine Bourguignon, Curator, Terra Foundation for American Art, and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional resources

This painting at the Terra Foundation for American Art

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

When the department store was new: Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones, The Shoe Shop

by DR. ANNELISE MADSEN, THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones, The Shoe Shop, c. 1911, oil on canvas, 99.1 x 79.4 cm (Art Institute of Chicago). Speakers: Dr. Annelise Madsen, Gilda and Henry Buchbinder Assistant Curator of American Art, The Art Institute of Chicago and Dr. Beth Harris

Symbolism

Henry Ossawa Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Banjo Lesson

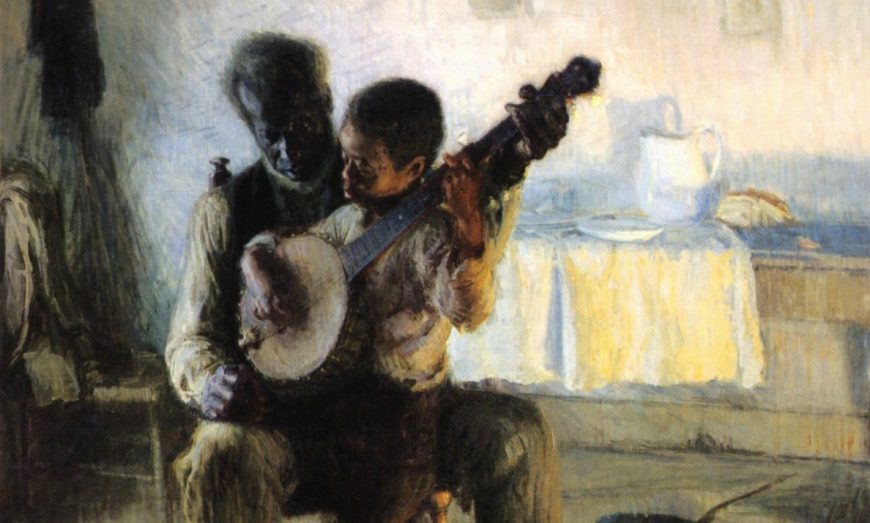

Henry Ossawa Tanner was the United States’ first African-American celebrity artist. His training at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (under the guidance of Thomas Eakins) and at the Académie Julian in Paris (with Jean-Léon Gérôme) put him in the unique position of having experienced two vastly different approaches to painting— American Realism and French academic painting. He was also one of the few artists to have had such training at a time when there were many barriers to education for African-Americans. Though Tanner lived most of his life in France and became well known for his lush biblical paintings, The Banjo Lesson is his most famous work and the painting that has become emblematic with his oeuvre.

Henry Tanner painted The Banjo Lesson in 1893 after a series of sketches he made while visiting the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina four years before. Tanner had been studying and working in Paris until he developed a bout of typhoid fever and was advised to return to the United States to recover his health and dwindling finances. While taking up a teaching post at Clark University in Atlanta, Tanner’s doctor told him to take in some mountain air. His trip to North Carolina opened his eyes to the poverty of African-Americans living in Appalachia.

The legacy of slavery

The United States had abolished slavery only twenty-four years before, in 1865, and the physical and psychological wounds of that brutal institution would continue to be a palpable presence in African-American communities—especially so in the South. Though Tanner was born in Pittsburgh within the tight-knit world of highly-educated members of America’s burgeoning African-American intelligentsia, Tanner’s mother Sarah had been born a slave and had escaped north to Pennsylvania through the Underground Railroad. His middle name, Ossawa, was chosen by his father, Benjamin Tucker Tanner, a Methodist minister and abolitionist, after Osawatomie, Kansas—the site of the abolitionist John Brown’s bloody confrontation with pro-slavery partisans on August 30, 1856.

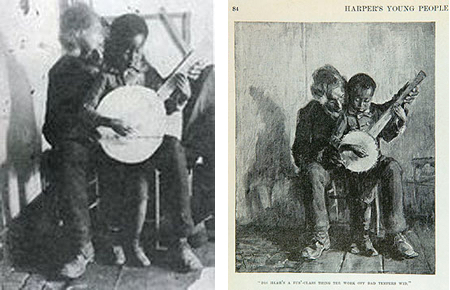

Throughout his education and advancement in the art world in both the United States and Europe, the legacy of slavery haunted Tanner as he tried to establish a niche for himself as painter to be regarded on his own terms. The Banjo Lesson grew out of a set of photographs and illustrations (above) that Tanner made for the periodical Harper’s Young People in 1893. The illustration is of an elderly man teaching a young boy how to play the banjo, accompanied a short story by Ruth McEnery Stuart called “Uncle Tim’s Compromise on Christmas,” in which the titular character imparts his most prized possession, a banjo, to his grandson on Christmas morning.

American realism + the European tradition

Tanner had spent years been refining a style of his own that combined elements of American Realism and the European Old Master tradition. The Banjo Lesson has its roots in the genre paintings of African-Americans by William Sidney Mount and Thomas Eakins (above) and in Renaissance and Flemish paintings, notably Domenico Ghirlandaio’s An Old Man and His Grandson and Johannes Vermeer’s Woman with a Lute (below).

While studying in Paris, Tanner was also inspired by the works of the French Realists, namely Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, in their depictions of the rural poor. Millet’s The Angelus, with its quiet, intensely spiritual portrayal of a farmer and his wife praying amid the fields at dusk, is a palpable influence on Tanner’s The Banjo Lesson.

A radically different image

This theme of spiritual solace that Tanner encountered in the paintings of French Realists like Millet resonated with his own upbringing as the son of a Methodist minister. He hoped to find a way of highlighting the dignity and grace of poor African-Americans in the manner that he had seen in France—an approach that would be radically different from stereotypical images of the overly servile “Uncle Tom” figure (named after the main character in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s iconic 1852 novel) that was familiar to Americans in countless advertisements (like this one, for Ayer’s Cathartic Pills [The Country Doctor], c. 1883) and popular magazines.

In The Banjo Lesson, Tanner’s desire to show us his vision of the resilience, spiritual grace, and creative and intellectual promise of post-Civil War African-Americans is fully realized. The scene is staged within the small confines of a log cabin with the cool glow of a hearth fire casting the scene’s only light source from right corner, enveloping the man and the boy in a rectangular pool of light across the floor. The boy holds the banjo in both hands, his downward gaze a reflection of his focused concentration on his grandfather’s instructions. The older man holds the banjo up gently with his left hand so that the boy is not encumbered by its weight, yet the staging shows us that the man wants the boy to come into the realization of the music and its rewards through his own intuition and hard work.

The contrast between the man’s age and the boy’s adds to the narrative tension within in the painting as in the Ghirlandaio, a counterpoint between age and experience, and youth and the promise of achievement. The boy is bathed in the glow of the fire’s warmth with a glimmer of white light shining across his forehead, the center of knowledge and understanding. The older man is submerged in the cool shadows of the room. This carefully orchestrated play of warm and cool, of shadow and light, conveys that the success of future generations is built upon the legacy of previous ones. Bathed in muted cool tones of grays and blues, the grandfather is the past, the old America of slavery and The Civil War, of oppression, racism, and poverty, while the boy, caught in the warm glow of the fire’s light, is the new America, of renewed opportunities, advancement, education, and new beginnings.

Banjos, minstrel shows, and stereotypes of African-Americans

Certainly Tanner would have seen a great deal of his own life played out in this tender scene. As the educated son of a former slave and a minister and abolitionist, Tanner was always striving to live up to his potential as an artist in the post-Civil War, post-Reconstruction era America. It is also important that the instrument that leads the boy towards enlightenment is the banjo, an instrument highly significant to African-American slave culture and the music of the American South. The banjo evolved from the gourd instruments of Africa and the West Indies and became integral to slave music throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

By Tanner’s time, it was a mainstay of minstrel shows, popular variety entertainment that featured white actors in blackface performing songs and skits. In minstrel shows, it was the custom to portray African-Americans as boisterous, jaunty, buffoonish, and dim-witted. This portrayal fed into the preconceived notions of white racial superiority—that African-Americans, even if they were no longer slaves, would still be infantile and incapable of self-determined action or remarkable achievements. The entire visual and popular culture of Uncle Tom imagery and minstrel shows were part of the pernicious psychological chains of slavery that persisted in America throughout much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The shows also depicted African-Americans as having an innate musicality, which acknowledged their talent but undermined their intelligence.

For Tanner, painting this image of generational torch-passing, was a way of debunking the entrenched derogatory stereotypes of African-Americans propagated by minstrel shows. In Tanner’s painting we see the grandfather and the boy as intelligent, noble, graceful people engaged in an intimate act of sharing creative knowledge. Their lesson becomes emblematic of the larger African-American journey of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, from Emancipation, Reconstruction, the terrors and injustices of the Jim Crow laws, the exodus of the Great Migration, and the foment and dynamism of the Harlem Renaissance.

An American artist

After painting The Banjo Lesson and The Thankful Poor (above), Tanner moved back to Paris where he would remain for most of his life. Tanner felt that France was less encumbered with the baggage of racial prejudice towards people of color than the United States. “In America, I’m Henry Tanner, Negro artist, but in France, I’m ‘Monsieur Tanner, l’artiste américaine.‘”\(^{[1]}\)

His desire to be recognized by the quality of his talent would inspire him to paint prolifically throughout his life, traveling through the Middle East and North Africa in search of authentic imagery for biblical paintings that would become the hallmark of his later career. When World War I was declared in Europe, Tanner enlisted in the Red Cross, serving as a medical volunteer as well as making numerous sketches and various paintings of the soldiers in France and Belgium. In 1923, he was awarded the Legion of Honour by the French government for his service during the war.

But it is The Banjo Lesson that has become the iconic painting of his entire career. Its economy of scale, its emotional delicacy, its nuanced orchestration of light and shadow and symbolism situates it in a resonant space in American art history. Both The Banjo Lesson and The Thankful Poor were remarkable achievements for Tanner—works that according to the art historian Judith Wilson, “invest their ordinary, underprivileged, Black subjects with a degree of dignity and self-possession that seems extraordinary for the times in which they were painted.”[2] It is a testament to Tanner’s vision as an artist, and his personal convictions as an African-American, amid the possibilities offered by twentieth century, that these two paintings continue to speak so profoundly to us now.

[1] Marcia M. Matthews, Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist (University of Chicago Press, 1995) p. 90.

Additional resources:

Henry O. Tanner, exhibition subsite from the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Anna O. Marley, ed. Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit (University of California Press: 2012).

Marcia M. Matthews, Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist (University of Chicago Press: 1995).

Kristin Schwain, Signs of Grace: Religion and American Art in the Gilded Age (Cornell University Press: 2007).

Judith Wilson, “Lifting ‘The Veil’: Henry O. Tanner’s The Banjo Lesson and The Thankful Poor,” Contributions in Black Studies: A Journal of African and Afro-American Studies, volume 9, article 4.

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Angels Appearing before the Shepherds

Henry Ossawa Tanner’s evocative Angels Appearing before the Shepherds compels us to ask larger questions: what is the purpose of art that depicts religious subjects? Can the visual arts dramatize the Biblical word in a way that text cannot? Tanner grappled with these questions in a painting depicting a scene from the New Testament when angels appeared before the shepherds in Bethlehem to announce the birth of Jesus. In doing so, he followed in the footsteps of many artists—like those that crafted the stained glass windows at Reims Cathedral depicting Christian angels and saints or the craftsman that sculpted bronze statues of Hindu gods in 11th century India—who used the power of visual representation for religious messages.

Tanner, his formation and influences

Henry Ossawa Tanner was the first African-American painter to gain critical recognition outside of the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century. Trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts under the guidance of Thomas Eakins and then at the Académie Julian in Paris with Jean-Léon Gérôme, Tanner’s remarkable talent and experience was highly unique for a man of his position and race in post-Civil War America.

Though Tanner painted his most well-known works, The Banjo Lesson (1893) and The Thankful Poor (1894), in a more naturalistic style, he painted Angels Appearing before the Shepherds in a more abstract, Symbolist style. The painting reflects his lifelong fascination with Christianity and the stories of the Bible. Tanner’s father, Benjamin Tucker Tanner, was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Pittsburgh and a political activist for the abolition of slavery, and religion played an important role in Tanner’s life and art.

Tanner completed this painting a few years after traveling to the Middle East in 1897. His first major biblical paintings, Daniel in the Lions’ Den (1896) and The Resurrection of Lazarus (1897) (below), gained critical acclaim in the Paris Salon (the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts). The art critic Rodman Wanamaker funded a trip for Tanner to visit the Middle East claiming that any serious artist who wanted to paint biblical scenes with conviction should familiarize himself with the Holy Land. From the experience of his travels, Tanner evokes the various shades of blue in the twilight sky of Jerusalem along the hills of Bethlehem.

Tanner’s painting of the angel and shepherds is a familiar subject for many artists like Rembrandt, Castiglione, and Thomas Cole. He depicts the pivotal scene of revelation, but renders it in a more lush and atmospheric tone than seen in the work of previous painters. Tanner’s exposure to the work of the post-Impressionists and the Symbolists in Paris in the 1890s seems to influence his hazy melding of color and line. The work of Odilon Redon, in particular, is a strong influence in this depiction of the multi-formed angel and in the blending of cool muted colors to echo the tones of pastels.

Looking closely at the painting, we have to ask ourselves what was the artist thinking in choosing to paint this dramatic scene in blue. Why would Tanner depict such an important scene of spiritual revelation in shadowy tones and cool colors?

Color and tranquility

Around the time Tanner painted this, the work of the Symbolist painters was at the vanguard of new intellectual thought in art in Paris, a group which included Paul Gauguin, Odilon Redon, and Gustave Moreau. The Symbolists were influenced by the color theories of German artist Franz von Stück, who was in turn influenced by Johan Wolfgang von Goethe’s important theory of color published in 1810. According to Goethe, colors, in addition to their inherent optical and scientific qualities, possessed psychological qualities as well. Stück explained that blue exuded mystery, eternity and calm. Through his modulated use of shades of blue and gray, Henry Tanner’s painting exudes the tranquility of God’s spiritual grace.

Beyond the colors, it is also important to consider our perspective as viewers into the painting. By situating our point-of-view from behind the angels, we look down at the distant figures of the shepherds below. Tanner enhances our sense of wonder by heightening the illusion of flight, the vastness of the landscape, and smallness of the shepherds within the aerial view.

Tanner’s evolving style

This painting is emblematic of Tanner’s evolving style in the middle part of his unique career. The critical acclaim of The Banjo Lesson made him wary that he might be restricted to painting tender scenes of rural life among black Americans, which would have been limiting to a man of his diverse interests and cosmopolitan background. In Angels Appearing before the Shepherds, we see Tanner move from the more traditional, naturalistic style of The Banjo Lesson, inspired by the work of Vermeer and the light-infused paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, to the more visionary approach of the Symbolists.

The influence of the nineteenth-century Romantic painters is also a palpable influence. In the cool blue glow of light along the Judean hills, Tanner evokes the moon paintings of Caspar David Friedrich (below), whose work inspired other American artists like Childe Hassam and Frederic Remington. Like Friedrich, who brings his spectator into a hushed communion with his cloaked subjects and the otherwordly eminence of nature and God, in Angels Appearing before the Shepherds, Tanner represents a time, tone, and scene conducive to a mood of spiritual reflection. As the art historian Alexander Nemerov describes Friedrich’s paintings, “the figures not only stand for the audience outside the canvas, but show us how to behave in the presence of moonlight—with awe and reverence.”

To an early twentieth-century European and American audience, the grandeur of biblical imagery in art was embodied by the traditional style of Rembrandt, Rubens, and the painters of the Spanish Baroque. Henry Tanner hoped to redefine religious painting in the twentieth century and to prove that an American—a black American—could create incisive and moving religious art on par with the work of the European Masters. Tanner proved that the visual representation of the Bible could indeed continue to be fresh, modern and highly relevant and accessible to any contemporary age.

Additonal Resources:

This painting at the Smithsoinian American Art Museum

Anna O. Marley, ed., Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit (University of California Press, 2012).

Kristin Schwain, Signs of Grace: Religion and American Art in the Gilded Age (Cornell University Press, 2008)

Alexander Nemerov, “Burning Daylight: Remington, Electricity, and Flash Photography,” Nancy Anderson, ed., Frederic Remington: The Color of Night (Washington, D.C., The National Gallery of Art, 2003).

John Gage, Color and Meaning: Art, Science, and Symbolism (University of California Press, 1999).

Marcia Matthews, Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist (University of Chicago Press, 1969).

The Ashcan School

A maverick group of painters in New York City set the foundation for depicting life in the changing, surging metropolis.

c. 1908 - 1940

The Ashcan School, an introduction

Populist, expansive, and committed to documentary realism

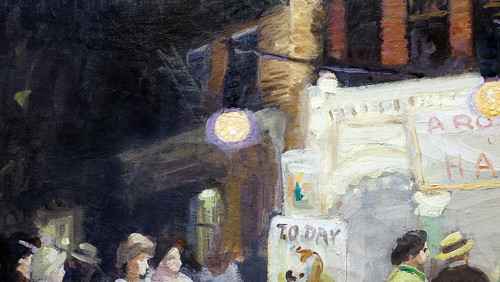

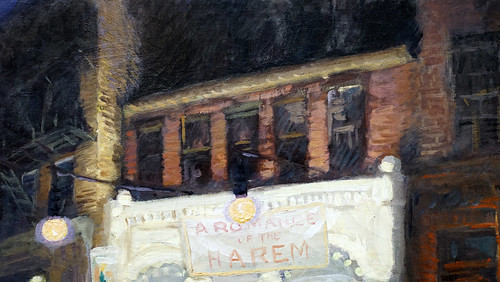

In the early part of the twentieth century, a maverick group of painters in New York City set the foundation for depicting the sheer variety and scale of life in the changing, surging metropolis. Their name, like that of the Impressionists, was initially a term of derision branded by the prevailing critics, though it ultimately became their banner of pride. The painters of the Ashcan School wanted to create a new kind of art rooted in the raw, visceral day-to-day reality of the city—not the New York that was depicted by the popular painters of the time, the American Impressionists William Merritt Chase and Childe Hassam—the decidedly posh, haute bourgeoisie New York of Park Avenue, Central Park, and Washington Square—but the New York of the Lower East Side and the Bowery, of newly arrived immigrants, dockworkers, nightclub performers, saloonkeepers, boxers, and the average worker trying to make ends meet while squeezing whatever small pleasure there was to be had out of life.

Their art was populist, expansive, and committed to a documentary realism that was far-reaching and ahead of its time. The poetry of Walt Whitman, the prose of Stephen Crane and Theodore Dreiser, the plays of Eugene O’Neill, and the music of ragtime and Tin Pan Alley comprised their emotional and spiritual soundtrack. The painting above by George Bellows of Madison Square at the intersection of Broadway and Twenty-third Street echoes the panorama and rhythms of Whitman’s 1888 poem, “Mannahatta”:

“I WAS asking for something specific and perfect for my city,

Whereupon, lo! upsprang the aboriginal name!I see that the word of my city is that word up there,

Because I see that word nested in nests of water-bays, superb, with

tall and wonderful spires…Numberless crowded streets—high growths of iron, slender, strong,

light, splendidly uprising toward clear skies…Immigrants arriving, fifteen or twenty thousand in a week;

The carts hauling goods—the manly race of drivers of horses—the brown-faced

sailors;

The summer air, the bright sun shining, and the sailing clouds aloft;

The winter snows, the sleigh-bells—the broken ice in the river,

passing along, up or down, with the flood tide or ebb-tide…The mechanics of the city, the masters, well-form’d, beautiful-faced,

looking you straight in the eyes;

Trottoirs throng’d—vehicles—Broadway—the women—the shops and

shows,

A million people—manners free and superb—open voices—hospitality—

the most courageous and friendly young men;The free city! no slaves! no owners of slaves!

The beautiful city, the city of hurried and sparkling waters! the

city of spires and masts!

The city nested in bays! my city!”

The sparkling subject of Whitman’s poem—the expanse of city landscape and life in all its diversity, color, and noise—is at the core of what the Ashcan School painters depicted in much of their work. They wanted to show New York City as it evolved from a sleepy Dutch island into the vital cultural capital of America.

Too many pictures of ashcans?

The Ashcan School formed out of an urge to rebel against the dogmatic criteria of popular painting of the time, namely American Impressionism and academic realism. In the spring of 1907, the Philadelphia-trained painter Robert Henri rallied his friends, John Sloan, Everett Shin, Arthur Davies, Ernest Lawson, Maurice Prendergast, William Glackens, and George Luks when Luks’ painting, Man with Dyed Mustachios, was rejected by the conservative National Academy for their Spring Exhibition.

Working together with the prominent Fifth Avenue dealer, William Macbeth, the group set up their first major exhibition at The Macbeth Gallery in February 1908 called Eight American Painters, which later became known simply as “The Eight.” Though he did not participate in the show, the other Ohio-born painter in the group, George Bellows, also joined the Ashcan artists in creating iconic paintings of the city in all its gritty splendor. Their work struck a nerve among emerging collectors: Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney purchased four paintings from the show that would become the basis for the permanent collection of her Whitney Museum of American Art.

It was eight years later, however, in 1916, that the group got their evocative name. John Sloan, Robert Henri, and George Bellows were also illustrators for the well-known socialist magazine, The Masses, and one of their staff members voiced a complaint that there were too many “pictures of ashcans and girls hitching up their skirts on Horatio Street.” The artists were amused and flattered, and the name stuck.

Painting true to life

In the 1920s, John Sloan spoke of how the unofficial leader of the group was Robert Henri, a distant cousin of Mary Cassatt’s and the son of a professional gambler and real estate developer who once shot a man to death over a land dispute:

It was really Henri’s direction that made us paint at all, and paint the life around us. The American genre painters Winslow Homer, Eastman Johnson, and William Sidney Mount had painted life around them, but we thought their work was too tight and finished. There were many other artists drawing for newspapers in Chicago, San Francisco…but they did not turn to painting. I feel certain that the reason our group in Philadelphia became painters is due to Henri. 1

Painting true to life was the key to the Ashcan School’s visual distinction in subject matter and fame. Like the artists of nineteenth century France, Honoré Daumier, Édouard Manet, and Gustave Courbet, the Ashcan painters captured those fleeting scenes of everyday life among the middle and lower classes at work and at leisure.

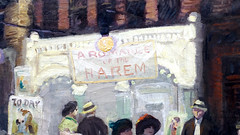

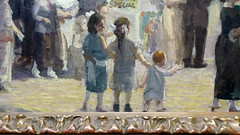

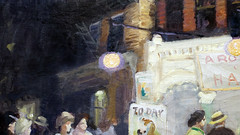

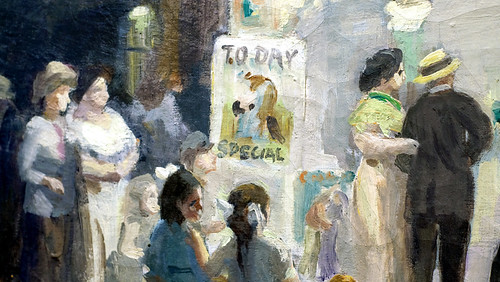

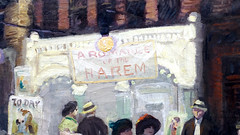

Paintings like William Glackens’ Hammerstein’s Roof Garden (left), John Sloan’s Chinese Restaurant (above), and George Bellows’ Stag at Sharkey’s (above), show the sheer variety of entertainment that the city had to offer with people reveling in the moment regardless of propriety and decorum. There is a documentary feel and intense presentness to the scenes depicted, from the woman feeding the cat in the John Sloan painting to the man with the cigar turning his face towards us in the George Bellows, we get an immediate sense of the vitality and evanescence of a society in transition, a newly emergent urban middle class with enough money and time for the short transitory pleasures of the city.

There were also paintings of longshoremen, laundresses, bartenders, and waitresses, all a part of a dynamic working class. The influx of immigration to America from Europe filled the workforce in cities, driving down demand and allowing employers to reduce wages. Many people became part of what was known as “the working poor,” living payday-to-payday. The Danish-American photographer Jacob Riis exposed the staggering poverty and squalor of the Lower East Side’s residents in his groundbreaking series, How the Other Half Lives (1890).

The Ashcan painters were generally not as direct and confrontational as Riis in his “muckraking” approach to social reform. They were not reformers, or even explicitly political, aside from illustrating for The Masses and frequenting occasional Socialist salons, which was the fashion among intellectuals in New York City at the time. The artists of the Ashcan School would not adopt political doctrine as did some contemporaneous movements in Europe, such as the Constructivists, who were decidedly more political and utopian in its aims. Rather, the Ashcan painters wanted to depict the American worker in a straightforward manner devoid of cant and propaganda: revealing the simplicity and beauty of the American at work and at play.

It’s important to remember the painters of the Ashcan School didn’t limit themselves to scenes of the city and its people but also painted a variety of pastoral landscapes. John Sloan and Robert Henri, who both had a classical training under Thomas Anschutz at The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, felt that the role of the American painter of the twentieth century was not confined to a specific social agenda but involved an expansive application of techniques and methods in a variety of genres.

Robert Henri’s Cumulus Clouds, East River (above) depicting a sunset and a swirling mass of thick coral cloud along the docks of Upper New York Bay, has echoes of the seascapes of nineteenth-century Romanticism, particularly those of J.M.W. Turner. John Sloan’s Sunflowers at Rocky Neck (below) painted along the coast of Gloucester, Massachusetts, was based in part on the swirling vibrancy of Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888), which Sloan saw at the Armory Show of 1913 in New York along with other works of European Post-Impressionism and modernist painting.

Sloan along with Henri had helped organize The Armory Show, which was a turning point for modern art in America. The public’s exposure to avant-garde work by artists like Marcel Duchamp, Paul Cézanne, Georges Braque, and Henri Matisse, among others, set the tone for the kind of art that Americans thought they should be making if they wanted to keep up with the tide of modernism across the world—art that was startlingly free of academic expectations of realism and conservative thought.

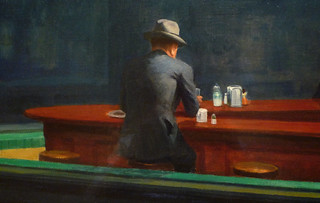

Food for starving souls

Though the Armory Show eventually helped propagate a new style of modern painting exemplified by artists like Stuart Davis (a student of Henri’s), Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove, and Georgia O’Keefe, the impact of the Ashcan School was far-reaching in American figurative painting for much of the twentieth century. The work of Edward Hopper (another of Henri’s famous pupils) owes a great deal to the subject matter and style of the Ashcan painters in terms of its propensity for human tableaus, theatricality, and detailed intimacy. Contemporaries of Hopper, Charles Burchfield and George Ault, were also inspired by the pioneering work of the Ashcan School, whose stylistic influence is palpable in their city scenes and melancholy vistas.

The lasting legacy of the Ashcan School is that for the first time in the twentieth century, American painting took on a populist commitment dedicated to depicting the reality of life in a changing, diverse, cosmopolitan society. Though the artists themselves never professed to be agents of social change they were bound together by a shared interest in providing meaningful and enjoyable artwork for a large audience: art for everyone and anyone. Writing in the 1930s, in his autobiography, John Sloan described the importance of art in everyday life as a fundamental need that is essential to one’s spiritual survival:

They say that art is a luxury because of the depression. But I really believe this is the time when people should turn to the artists. Not the artist whose work is selling for thousands, but the interesting work of men who sell their things for reasonable figures. I believe the work of artists, poets, musicians, is a kind of food for starving souls, as necessary as food for the body. Why should we worry about feeding bodies if they have starving souls? That may sound churchy but I don’t mean it so. Select your own soul-food in the way of art.2

What Sloan is espousing might seem naïve to some, but as a man who came of age in that period of American history between the end of The Civil War and through World War I, the Roaring Twenties, and the Great Depression, prosperity and poverty were two sides of a swiftly spinning coin in collective fortunes. Art had the ability to provide enlightenment, education, and spiritual fulfillment to an enormous audience, and the painters of the Ashcan School were among the first to expand its changing role in American life.

1. As quoted in Rebecca Zurier, Picturing the City: Urban Vision and the Ashcan School (University of California Press: Los Angeles, 2006), p. 25.

2. As quoted in John Sloan on Drawing and Painting: The Gist of Art (Dover Publications: New York, 2010), p. 26.

Additional resources:

The Ashcan School on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Bernard Perlman, Painters of the Ashcan School: The Immortal Eight (Dover Publications: New York, 2012).

Rebecca Zurier, Picturing the City: Urban Vision and the Ashcan School (University of California Press: Los Angeles, 2006).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

George Benjamin Luks, Street Scene (Hester Street)

by MARGARITA KARASOULAS, ASSISTANT CURATOR OF AMERICAN ART, BROOKLYN MUSEUM and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): George Benjamin Luks, Street Scene (Hester Street), 1905, oil on canvas, 65.5 x 91.1 cm (Brooklyn Museum, 40.339, Dick S. Ramsay Fund) Speakers: Dr. Margarita Karasoulas, Assistant Curator of American Art, Brooklyn Museum and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional Resources

George Bellows

George Bellows, Pennsylvania Station Excavation

by MARGARITA KARASOULAS, ASSISTANT CURATOR OF AMERICAN ART, BROOKLYN MUSEUM and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): George Bellows, Pennsylvania Station Excavation, c. 1907–08, oil on canvas, 79.2 x 97.1 cm (Brooklyn Museum), a Seeing America video Speakers: Dr. Margarita Karasoulas, Assistant Curator, American Art, Brooklyn Museum and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional resources

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

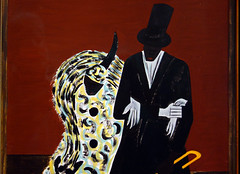

George Bellows, Both Members of This Club

by ABBY R. ERON

In the early twentieth century, the artist George Bellows aspired to represent the rough edges and dark aspects of New York City. In his early twenties, Bellows moved to the city from Ohio, where he had attended the Ohio State University and played baseball and basketball. He studied with Robert Henri at the New York School of Art and became part of an informal group of American artists that came to be called the “Ashcan School” due to the painters’ gritty brand of realism and the apparent muddiness of their color palettes. Henri, who led the group, encouraged his associates, a number of whom had been illustrators in Philadelphia, to sketch and paint from real life. Typical subjects for Henri, Bellows, and their Ashcan brethren included rough-and-tumble youths, working class people, immigrant communities, and the hubbub of the urban street. While still in his twenties, Bellows painted Both Members of This Club (1909), one of his most recognizable images.

Style, composition, and color

In the painting, two men, one white and the other black, on the left and right respectively, engage one another in a prizefighting (boxing for cash prize) ring. The painting’s style reinforces its subject matter. Bellows’ brushstrokes underscore the violence, physicality and vigorous action of the match. Bellows applied paint with a quickness and sketchiness that echoes the energetic movement of the athletes and the flickering of low light as it bounces across the faces of the rowdy, restless audience. The forms, while distinct, are not delicately rendered, but instead are roughly described. Slashes of paint are particularly noticeable in the highlights along the black boxer’s back and side. They are also apparent in the streaks of red, evoking blood, by the elbow of the white boxer, along his ribs and stomach, and across his neck and chin.

The composition is approximately triangular with the apex marked by the collision of the boxers’ upraised fists. The fighter on the right lunges forward, gaining momentum by pushing off an extended and unnaturally attenuated right leg, into the left fighter, whose right knee seems ready to buckle beneath him. Several layers of the crowd define the base of this compositional triangle.

Bellows mostly limited the colors in this painting to shades of blue-gray, brown, and cream, but accentuated this tonal palette with touches of white, red, orange, and pink, plus the green of the left boxer’s trunks. Bellows illuminated the composition to spotlight the action, thus associating the ring with a theater stage. The obscure darkness of the background largely precludes any perception of recession into space, and also creates the feeling of a dangerous and secretive atmosphere. Indeed, the title Both Members of This Club refers to the dubious practice of turning boxers into temporary sports club members in order to skirt a New York state law that prohibited public prizefighting. For a time, Bellows lived across the street from Sharkey Athletic Club (one institution that took part in this subterfuge), where he could readily observe men fighting.

Race and boxing

Bellows keyed in to the racial dynamics of his era by pitting a black fighter against a white fighter. He showed Both Members of This Club at the Exhibition of Independent Artists in 1910, the year of a much-anticipated fight between heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson and his challenger Jim Jeffries. The media billed Jeffries as the latest in a series of “great white hopes” who aspired to take the coveted heavyweight title away from Johnson, the African-American man who had held it since 1908. Racial animosity dramatized coverage of the fight, a contest in which Johnson ultimately proved victorious. Though the matchup in Both Members of This Club cannot be definitively assigned to any particular boxing bout, race is thematically and compositionally central in Bellows’ scene. The painting’s title registers as darkly satirical when we realize that, during this period of segregation, fighting—especially illicit prizefighting at a place such as Sharkey’s—was one of the few forums in which membership could be conferred equally and close interracial interaction condoned.\(^{1}\)

The crowd and the city

Bellows’ painting also reflects a contemporary interest in crowd psychology (the study of how individuals behave differently as part of a crowd as well as the behavior of the crowd itself). Bellows famously claimed that “the atmosphere around the fighters is a lot more immoral than the fighters themselves.” In Both Members of This Club, Bellows exaggerated the faces of the onlookers. They grimace, shout, and stare bug-eyed at the drama before and above them. Particularly startling is the toothy grin of a spectator with a long face who can be spotted just to the right of the black boxer’s foreshortened left foot. Bellows’ incisive depiction of the match’s audience reveals the influence of nineteenth-century French artist and caricaturist Honoré Daumier, but it also points to societal concerns of Bellows’ day.

Bellows painted this canvas in 1909, the year after the publication of what are often considered the first two social psychology textbooks. The books’ authors, sociologist Edward Alsworth Ross and psychologist William McDougall, both explored crowd psychology. Ross wrote about the dissolution of individual identity within a crowd, and the crowd’s increased susceptibility to waves of emotion over logical reasoning. Similarly, McDougall theorized that being part of a crowd was a definitive condition of human recreation, stemming from what he referred to as the “gregarious impulse.” He also argued that this “gregarious impulse” was evidenced by the undeniable appeal of cities, which continued to attract residents (such as Bellows himself) despite the high cost of living, pollution, congestion, and risk for disease.2

Urban entertainments

Critics considered Bellows to be distinctly American because he never studied abroad in Europe, as so many other American artists at the time did. Yet Bellows’ work was not insular. His boxing pictures relate to images that fellow Ashcan artist Everett Shinn created of the theater. Shinn was in turn deeply influenced by the work of French Realist and Impressionist Edgar Degas. However, comparison with Shinn and Degas highlights what distinguishes Both Members of This Club. Rather than depicting the polite urban recreation of theater attendance, as in Shinn’s The White Ballet from 1904, Bellows blatantly exposed the city’s dingy and nearly illegal underside, featuring an all-male space where brutality and head-to-head conflict replaced the glamour and coordination of ballet performance.

Part of the crowd?

Both Members of this Club is one of three boxing paintings Bellows made in the first decade of the twentieth century. As in the other two, Club Night (1907) and Stag at Sharkey’s (1909), Both Members of This Club places its viewers in an ambivalent position. We are implicated as part of the bloodthirsty crowd directly behind the heads of the front row spectators, while simultaneously separated from this crowd as visitors in the hushed and refined space of an art gallery.

1. Marianne Doezema, George Bellows and Urban America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), pp. 104-113.

2. Arie W. Kruglanski and Wolfgang Stroebe, “The Making of Social Psychology,” in Handbook of the History of Social Psychology, ed. Arie W. Kruglanski and Wolfgang Stroebe (New York: Psychology Press, 2012), p. 3; Edward Alsworth Ross, Social Psychology: An Outline and Sourcebook (New York: MacMillan, 1908), pp. 45-46; and William McDougall, An Introduction to Social Psychology, 2nd ed. (Boston: John W. Luce, 1909), pp. 86, 297.

Additional Resources:

This painting at the National Gallery of Art

The Aschcan School at the Timeline of Art History (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Bellows, Return of the Useless

by DR. JENNIFER PADGETT, CRYSTAL BRIDGES MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): George Bellows, Return of the Useless, 1918, oil on canvas, 149.9 x 167.6 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art), a Seeing America video Speakers: Dr. Jen Padgett, Associate Curator, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional resources

This painting at The Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

The Bryce Report at the British Library

John Sloan, Movies

by DR. LAWRENCE W. NICHOLS, TOLEDO MUSEUM OF ART and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): John Sloan, Movies, 1913, oil on canvas, 50.3 61 cm (Toledo Museum of Art)

Additional resources

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

291 and the American avant garde

This New York gallery led by Alfred Stieglitz was at the forefront of modernist painting and photography in the United States.

1908 - 1917

Alfred Stieglitz, The Steerage

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Alfred Stieglitz, The Steerage, 1907, photograph, 33.34 x 26.51 cm (includes black border), Museum Library Purchase, 1965 (LACMA M.65.76.1) A conversation with Eve Schillo, Assistant Curator, Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Beth Harris

First class

After his 8-year-old daughter Kitty finished the school year and he closed his Fifth Avenue art gallery for the summer, Alfred Stieglitz gathered her, his wife Emmeline, and Kitty’s governess for their second excursion to Europe as a family. The Stieglitzes departed for Paris on May 14, 1907, aboard the first-class quarters of the fashionable ship Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Although Emmeline looked forward to shopping in Paris and to visiting her relatives in Germany, Stieglitz was anything but enthusiastic about the trip. His marriage to status-conscious Emmeline had become particularly stressful amid rumors about his possible affair with the tarot-card illustrator/artist Pamela Coleman Smith. In addition, Stieglitz felt out of place in the company of his fellow upper-class passengers. But it was precisely this discomfort among his peers that prompted him to take a photograph that would become one of the most important in the history of photography. In his 1942 account “How The Steerage Happened,” Stieglitz recalls:

How I hated the atmosphere of the first class on that ship. One couldn’t escape the ‘nouveau riches.’ […]

On the third day out I finally couldn’t stand it any longer. I had to get away from that company. I went as far forward on the deck as I could […]

As I came to the end of the desk [sic] I stood alone, looking down. There were men and women and children on the lower deck of the steerage. There was a narrow stairway leading up to the upper deck of the steerage, a small deck at the bow of the steamer.

To the left was an inclining funnel and from the upper steerage deck there was fastened a gangway bridge which was glistening in its freshly painted state. It was rather long, white, and during the trip remained untouched by anyone.

On the upper deck, looking over the railing, there was a young man with a straw hat. The shape of the hat was round. He was watching the men and women and children on the lower steerage deck. Only men were on the upper deck. The whole scene fascinated me. I longed to escape from my surroundings and join these people.

In this essay, written 35 years after he took the photograph, Stieglitz describes how The Steerage encapsulated his career’s mission to elevate photography to the status of fine art by engaging the same dialogues around abstraction that preoccupied European avant-garde painters:

A round straw hat, the funnel leading out, the stairway leaning right, the white drawbridge with its railings made of circular chains – white suspenders crossing on the back of a man in the steerage below, round shapes of iron machinery, a mast cutting into the sky, making a triangular shape. I stood spellbound for a while, looking and looking. Could I photograph what I felt, looking and looking and still looking? I saw shapes related to each other. I saw a picture of shapes and underlying that the feeling I had about life. […] Spontaneously I raced to the main stairway of the steamer, chased down to my cabin, got my Graflex, raced back again all out of breath, wondering whether the man with the straw hat had moved or not. If he had, the picture I had seen would no longer be. The relationship of shapes as I wanted them would have been disturbed and the picture lost.

But there was the man with the straw hat. He hadn’t moved. The man with the crossed white suspenders showing his back, he too, talking to a man, hadn’t moved. And the woman with a child on her lap, sitting on the floor, hadn’t moved. Seemingly, no one had changed position.

[…It] would be a picture based on related shapes and on the deepest human feeling, a step in my own evolution, a spontaneous discovery.

Hindsight

With this account, Stieglitz argues with the benefit of more than three decades of hindsight that The Steerage suggests that photographs have more than just a “documentary” voice that speaks to the truth-to-appearance of subjects in a field of space within narrowly defined slice of time. Rather, The Steerage calls for a more complex, layered view of photography’s essence that can accommodate and convey abstraction. (Indeed, later photographers Minor White and Aaron Siskind would engage this project further in direct dialogue with the Abstract Expressionist painting.)

Stieglitz is often criticized for overlooking the subjects of his photograph in this essay, which has become the account by which the photograph is discussed in our histories. But in his account for The Steerage, Stieglitz also calls attention to one of the contradictions of photography: its ability to provide more than just an abstract interpretation, too. The Steerage is not only about the “significant form” of shapes, forms and textures, but it also conveys a message about its subjects, immigrants who were rejected at Ellis Island, or who were returning to their old country to see relatives and perhaps to encourage others to return to the United States with them.

Ghastly conditions

As a reader of mass-marketed magazines, Stieglitz would have been familiar with the debates about immigration reform and the ghastly conditions to which passengers in steerage were subjected. Stieglitz’s father had come to America in 1849, during a historic migration of 1,120,000 Germans to the United States between 1845 and 1855. His father became a wool trader and was so successful that he retired by age 48. By all accounts, Stieglitz’s father exemplified the “American dream” that was just beyond the grasp of many of the subjects of The Steerage.

Moreover, investigative reporter Kellogg Durland traveled undercover as steerage in 1906 and wrote of it: “I can, and did, more than once, eat my plate of macaroni after I had picked out the worms, the water bugs, and on one occasion, a hairpin. But why should these things ever be found in the food served to passengers who are paying $36.00 for their passage?”

Still, Stieglitz was conflicted about the issue of immigration. While he was sympathetic to the plight of aspiring new arrivals, Stieglitz was opposed to admitting the uneducated and marginal to the United States of America—despite his claims of sentiment for the downtrodden. Perhaps this may explain his preference to avoid addressing the subject of The Steerage, and to see in this photograph not a political statement, but a place for arguing the value of photography as a fine art.

Additional Resources:

Marsden Hartley, Portrait of a German Officer

A different kind of portrait

I once hired a photographer to take my picture for a publication. The resulting portrait accurately shows what I looked like on a morning in January 2013: wavy brown hair with a receding hairline; narrow, pale blue eyes aided by black-rimmed spectacles; a smile with a thin upper lip; broad nose; clean-shaven face. It even shows what I wore that day: dark jeans, light blue shirt, brown tweed blazer. This image is an accurate representation of my appearance, but does it tell you anything about who I am? Would it be possible for a different kind of portrait do something else—could it instead depict aspects of my professional or personal identity rather than simply showing how I appear? If a painter filled a canvas with things that symbolize my life, could that image be just as meaningful an expression of who I am? This kind of “allegorical” or symbolic portrait was exactly what Marsden Hartley achieved in his 1914 Portrait of a German Officer, which he painted while living in Germany during the start of World War I.

New York, Paris and Berlin

Hartley was an American by birth and training: born in Maine, he moved to New York City in 1899, where he studied with the American painter William Merritt Chase and, later, at the National Academy of Design. In New York, he also met the preeminent avant-garde photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who owned and operated the prestigious 291 Gallery. Stieglitz not only gave Hartley a one-person show at the gallery, but he also introduced the 28-year-old painter to the newest trends in European modernism.

In 1912, Hartley packed his trunks and moved to Paris. There, he moved within artistic circles that included artists such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, who both influenced Hartley’s work. While in Paris, Hartley also met Arnold Rönnebeck, a German sculptor, and his cousin, Karl von Freyburg, who was then a lieutenant in the German army. He and Hartley became close, and a number of art historians have suggested that they were lovers. Hartley visited Rönnebeck and von Freyburg in Berlin in early 1913, and moved there just months later. He stayed through the start of the World War I in August 1914, and remained in Germany until December of 1915, when the war was fully and catastrophically underway. While in Germany, Hartley also met the German Expressionists Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, the founders of the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) movement. An examination of Hartley’s paintings during his Berlin years suggests that the abstraction of Kandinsky and Marc also had a profound effect on his work.

New modes of abstraction

Portrait of a German Officer is a great example of this abstraction, and it is clear that Hartley used elements from both Picasso’s Cubism and the German Expressionists to depict not what Karl von Freyburg looked like, but a portrait that alludes to who and what he was. The painting brings together a cluster of real-world objects in a manner that emulates Cubism—the practice, pioneered by Picasso and his collaborator Georges Braque, of deconstructing three-dimensional forms and reassembling them on a two-dimensional canvas. Hartley’s use of bright hues and dynamic, linear forms in the painting also display the impact of Kandinsky, who was at the time developing a painterly language of pure form and color designed to elicit spiritual and emotional responses from the viewer. In utilizing these new modes of abstraction to depict a person, Hartley fundamentally shifted both the nature and function of the traditional portrait.

Deciphering the portrait

Portrait of a German Officer is also a commemorative image of von Freyburg, who had died in October 1914, an early casualty of World War I. It is a surprisingly large canvas—about the height of a human being. Hartley has filled the composition with the pomp and pageantry of the military. Von Freyburg’s initials, “Kv.F,” are included in the lower left of the painting (left). The red number four on a dark blue field (below) refers to von Freyburg’s military regiment, and the yellow “24” refers to his age at the time of his death.

The letter “E” appears twice in the composition: the red, curvilinear E on a gold background in the middle of the painting (right) is a battalion marker that refers to the Bayerische Eisenbahn, the name of von Freyburg’s railroad battalion. A second cursive E on what looks to be an epaulette in the lower right could refer to either Hartley’s birth name, Edmund, or Queen Elisabeth of Greece, the royal patron of von Freyburg’s regiment. The silver star connecting to a serpentine line near the yellow 24 is a boot spur, referring to von Freyburg’s position as a cavalry officer (above). Finally, the stylized cross with white trim (see image at top of page) is a German Iron Cross—a medal awarded to soldiers who demonstrated exceptional valor. Von Freyburg earned this medal shortly before his death. If we imagine this vertical canvas as an analog to a human figure, this decoration might be understood as being worn on the chest, suspended from a red and white striped ribbon.

Hartley’s painting is also more than a portrait of an individual: it expresses the rising German nationalism that he witnessed while living in Berlin. The diagonal blue and white checkerboard pattern (left) is a reference to the flag of Bavaria, and so too are the pair of blue and white stripes on the right side of the image. The red, white, and black stripes on the bottom third of the canvas represent a Kriegsschiffgösch or German naval war flag, turned upside-down. This flag typically had a black cross in the middle of it, but Hartley omitted this element so as to bring compositional importance to the medal in the upper part of the painting. Beneath the German flag are the standards of two of Germany’s enemies: the red and white St. George’s Cross of England, and the black, yellow, and red tricolor of Belgium.

More than appearances

In western academic painting of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, veracity and naturalism (at least to the extent that they flattered the subject) were prized aspects of portraiture. The renowned early American portraitist Gilbert Stuart, for example, was said to have “nailed the face to the canvas.” Clearly, Marsden Hartley had no such interest in nailing any part of Karl von Freyburg’s body to the canvas. Instead, through the use of military and nationalistic accoutrements, Hartley created an allegorical visual ode to his friend, a portrait that says nothing about his appearance, but communicates much about who and what he was as a person.

Additional Resources:

View this work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Townsend Ludington, Marsden Hartley: The Biography of an American Artist, Cornell University Press, 1998.

The City at night, Joseph Stella’s The Voice of the City of New York Interpreted

by DR. TRICIA LAUGHLIN BLOOM and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Joseph Stella, The Voice of the City of New York Interpreted, 1920-22, oil and tempera on canvas (five panels), 99.75 x 270 inches overall (Purchase 1937 Felix Fuld Bequest Fund 37.288a-e, Newark Museum), a Seeing America video

Additional resources

Charles Demuth, I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold

by DR. LARA KUYKENDALL

Precisionism

Charles Demuth is known as a Precisionist, and many of his paintings apply the fractured visual language of cubism and the dynamism of futurism to distinctive American places like cities and factories. In the 1920s, Precisionists like Demuth, Charles Sheeler, and others were called the “Immaculates” because of the smooth surfaces, clean lines, and meticulous geometry of their images. In this vein, Demuth painted the church tower and rooftops of Provincetown, Massachusetts in After Sir Christopher Wren, 1920, the brand new grain elevators in his hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania in My Egypt, 1927, and New York City in I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, 1928.

From poem to painting

I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold was inspired by the poem, “The Great Figure,” written by Demuth’s friend, William Carlos Williams:

Among the rain

and lights

I saw the figure 5

in gold

on a red

firetruck

moving

tense

unheeded

to gong clangs

siren howls

and wheels rumbling

through the dark city.

Williams’ poem recalls a night when he was walking down Ninth Avenue in New York City on his way to painter Marsden Hartley’s studio. He heard the noises of a fire truck, only to turn around just as it was passing by. All he saw was the number of the truck, a five painted in gold, on a red background speeding past. At this moment in his career Williams was trying to create poems that were precise and concrete representations of original experiences, so he avoided symbolism and metaphor in favor of simple language that evokes the speed (“moving tense unheeded”), the sounds (“gong clangs siren howls and wheels rumbling”), and the images (rain, lights, firetruck, dark city) he witnessed. Reportedly, Williams wrote this one-sentence poem right there on the street that night.

Williams’ poetry is deliberately straightforward, but Demuth’s painting is complicated. You really must know the poem to decode the painting. The setting is a tunnel-like street, which is flanked by sidewalks and buildings. Much of this backdrop is gray and black, but for the illuminated shop windows and globular streetlamps on both sides. The fire engine dominates the middle of the composition and although its form is abstracted we can recognize it by its red color. We can see the truck’s ladder on the right, and a long bar stretches across the bottom of the truck, which resembles an axle with two wheels or roaring sirens. The little curved lines that radiate from those sirens or wheels can indicate sound, motion, or both.

Picturing motion

Demuth divided the picture plane into rectangles and triangles, which refract light and change the color of space and shapes. The diagonal lines force your eyes to race around as you try to understand the image. That identifying number five repeats very clearly three times in the center of the composition. The fives get larger as they surge into the foreground (or smaller as they recede into the background), and in the upper right corner you can glimpse the curve of a fourth five as it leaves the surface of the picture and enters your space. The echoing numbers evoke the fire truck as it races toward you and past. Demuth’s painting, with its prismatic chards of space and color and the recurring number five, visualizes the motion and mystery of Williams’ experience in a futurist way. It collapses an extended period of time onto one still canvas.

Poster portraits: symbolic and witty

In addition to representing Williams’ poem, Demuth designed I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold as a portrait of Williams. It is one of at least eight “poster portraits” that Demuth completed during the 1920s. All are abstract or symbolic representations of Demuth’s friends, which contain oblique references to their subjects’ identity instead of depicting them in bodily form. In I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, Demuth included Williams’ initials, W.C.W., at the bottom of the composition. His nickname Bill is cropped at the top, and his middle name Carlos emanates from a skyscraper in the distance (with the “s” on the end hidden behind another structure). These references to Williams are not terribly obvious, though, and they only make sense if you already know to associate Williams with this painting.

The poster portraits function as graphic advertisements for their sitters, but they also included puns or inside jokes that encode Demuth’s friendship with his subjects in more subtle ways. Carlos, which is how Demuth addressed Williams, consists of yellow dots like the light bulbs on an illuminated theater sign, making Williams into a Broadway star. Bill is high in the sky, as if on a billboard above a building, and is a pun on the word “bill,” which can mean poster or ad. Like I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, the poster portraits that Demuth made of his friends and fellow artists Georgia O’Keeffe and Arthur Dove incorporate their signature subject matter—fruits, plants, and landscapes—and their names, written in popular 1920s commercial fonts and bold colors.

O’Keeffe’s portrait practically shouts the letters of her last name, which people were always misspelling. Here Demuth is telling her (and us) that he knows her well enough to remember how many Es and Fs to include. In his poster portrait, Dove’s scythe has a red ribbon tied around it, a reference to his partner, the painter Helen Torr, who was known to friends as “Reds.” These witty details personalize the images, but only make sense if you know a bit about Demuth and his friends, which is perhaps why critics were slow to appreciate the cleverness of the poster portraits.

Symbolic portraiture as a modernist tactic

Symbolic or abstract portraiture was in vogue in Demuth’s day. Writer Gertrude Stein made word portraits of her friends, and Francis Picabia and Arthur Dove caricatured photographer and dealer Alfred Stieglitz as parts of a camera. Images like Marsden Hartley’s Portrait of a German Officer, 1914, a painted collage of symbols like flags, chessboards, and parts of a military uniform, are also important precedents for Demuth’s project. As modernists, all of these artists made works that are conceptually complicated, visually abstract, and exciting responses to the challenge of being innovative in the early twentieth century.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Corn, Wanda M. The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915- 1935. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

Haskell, Barbara. Charles Demuth. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1987.

Williams, William Carlos. Autobiography. New York: Random House, 1951.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Georgia O’Keeffe, The Lawrence Tree

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Georgia O’Keeffe, The Lawrence Tree, 1929, oil on canvas, 31 x 40″ (Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut)

This was painted in the summer of 1929 while visiting D.H. Lawrence at his Kiowa Ranch during O’Keeffe’s first trip to New Mexico. The tree stands in front of the house.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

American Modernism

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Little Joe with Cow

by DR. JENNIFER PADGETT, CRYSTAL BRIDGES MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Little Joe with Cow, 1923, oil on canvas, 71.1 x 106.7 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art), a Seeing America video, speakers: Dr. Jen Padgett, Associate Curator, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, and Dr. Beth Harris

Additional resources

Elsie Driggs, Blast Furnaces

by DR. JENNIFER PADGETT, CRYSTAL BRIDGES MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): Elsie Driggs, Blast Furnaces, 1927, oil on canvas, 83.8 x 99.1 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas, 2017.1), a Seeing America video Speakers: Dr. Jenn Padgett, Associate Curator, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional resources

Millard Sheets, Tenement Flats

by DR. VIRGINIA MECKLENBURG, SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{12}\): Millard Sheets, Tenement Flats, 1933 – 34, oil on canvas, 102.1 x 127.6 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum). A conversation with Dr. Virginia Mecklenburg, Chief Curator, Smithsonian American Art Museum and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional resources:

The American south and southwest

The lure of the American Southwest: E. Martin Hennings, Rabbit Hunt

by DR. JENNIFER HENNEMAN, DENVER ART MUSEUM and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{13}\): A conversation with Dr. Jennifer Henneman, Assistant Curator of Western American Art, Denver Art Museum, and Dr. Beth Harris about E. Martin Hennings, Rabbit Hunt, c. 1925, oil on canvas (Denver Art Museum)

Special thanks to the Denver Art Museum

Velino Shije Herrera (Ma Pe Wi), Design, Tree and Birds

by DR. ADRIANA GRECI GREEN and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{14}\): Velino Shije Herrera (Ma Pe Wi), Design, Tree and Birds, c. 1930, watercolor on paper, 25.25 x 17.75 inches (Newark Museum of Art, Gift of Amelia Elizabeth White, 1937, 37.216)

The Pueblo Modernism of Velino Shije Herrera.

Additional resources:

This work of art at the Newark Museum

The Modernist-Inspired Watercolors of a Pioneering Pueblo Painter

Bill Traylor

by JEFFREY WOLF

Video \(\PageIndex{15}\)

At the height of the Great Depression, Traylor moved to Montgomery to look for work and ultimately found himself homeless, and he began to draw.

Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts Trailer from jeffrey Wolf on Vimeo.

Harlem Renaissance

Aaron Douglas, Aspiration

by TIMOTHY ANGLIN BURGARD, FINE ARTS MUSEUMS OF SAN FRANCISCO and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{16}\): Aaron Douglas, Aspiration, 1936, oil on canvas, 152.4 x 152.4 cm (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco), a Seeing America video

Jacob Lawrence

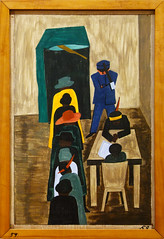

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Directly below is the shorter version of this video. You can access the longer version by scrolling down the page.

Video \(\PageIndex{17}\): Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, 1940-41, 60 panels, tempera on hardboard (even numbers at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, odd numbers at the Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.)

Video \(\PageIndex{18}\): Jacob Lawrence, The Migration Series, 1940-41, 60 panels, tempera on hardboard (even numbers at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, odd numbers at the Phillips Collection, Washington D.C.)

Additional resources:

The Migration Series at the Phillips Collection

The Migration Series at The Museum of Modern Art

A finding guide for images related to the Great Migration at the Library of Congress

A finding guide for primary documents related to the Great Migration at the Library of Congress

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

A Harlem street scene by Jacob Lawrence, Ambulance Call

by DR. JENNIFER PADGETT, CRYSTAL BRIDGES MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{19}\): Jacob Lawrence, Ambulance Call, 1948, tempera on board, 61 x 50.8 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art) Speakers: Jennifer Padgett, assistant curator, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art and Beth Harris

Additional resources:

This painting at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

Anna Diamond, “Why the Works of Visionary Artist Jacob Lawrence Still Resonate a Century After His Birth,” September 5, 2017) Smithsonian.com

Social Realism

Realism in the United States took a hard look at the nation's political and social conditions.

c. 1930 - 1945

Todros Geller, Strange Worlds

by SARAH ALVAREZ, THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{20}\): Todros Geller, Strange Worlds, 1928, oil on canvas, 71.8 x 66.4 cm (Art Institute of Chicago), a Seeing America videoSpeakers: Sarah Alvarez, Director of School Programs, Department of Learning and Engagement, The Art Institute of Chicago and Steven Zucker

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Grant Wood

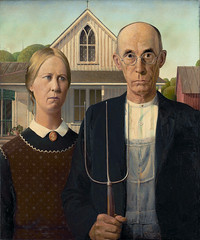

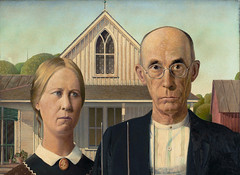

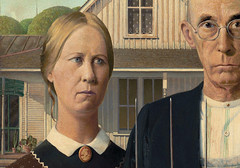

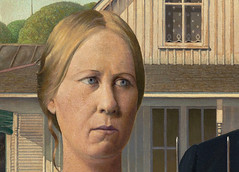

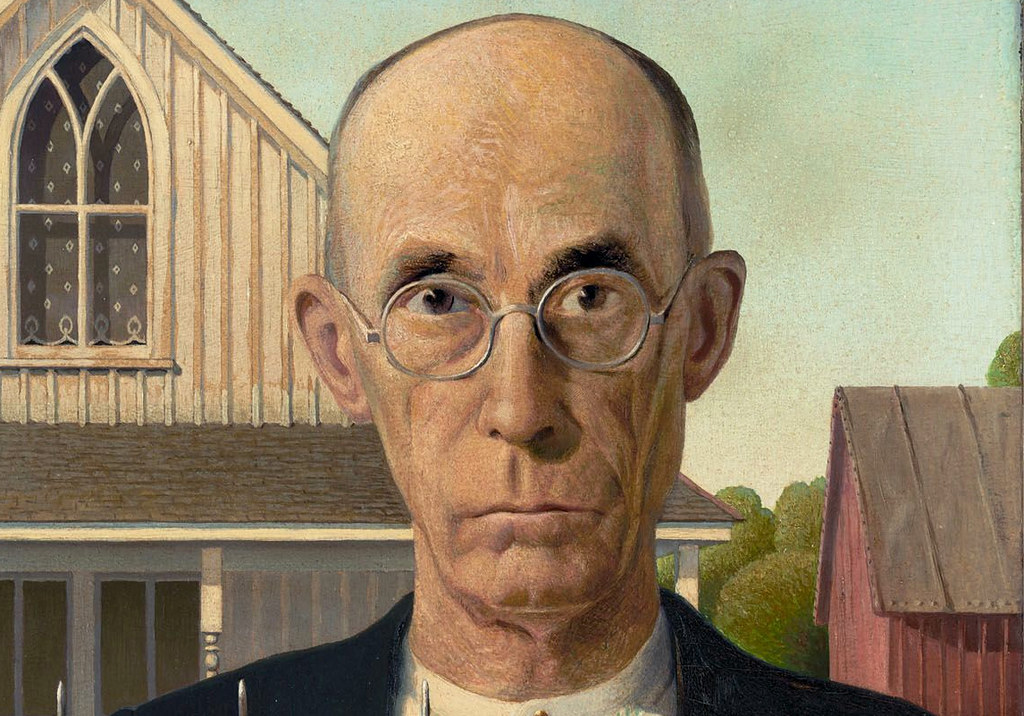

Grant Wood, American Gothic

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{21}\): Grant Wood, American Gothic, 1930, oil on beaver board, 78 x 65.3 cm / 30-3/4 x 25-3/4″ (The Art Institute of Chicago)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Grant Wood, Parson Weems’ Fable

by DR. SHIRLEY REECE-HUGHES, AMON CARTER MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{22}\): A conversation with Dr. Shirley Reece-Hughes, Curator, Amon Carter Museum of American Art and Dr. Steven Zucker in front of Grant Wood, Parson Weems’ Fable, 1939, oil on canvas, 38 1/8 x 50 1/8 inches (Amon Carter Museum of American Art)

Reginald Marsh, Wooden Horses

by ERIN MONROE, WADSWORTH ATHENEUM MUSEUM OF ART and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{23}\): Reginald Marsh, Wooden Horses, 1936, tempera on board, 61 x 101.6 cm (Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art). A conversation with Erin Monroe, Robert H. Schutz, Jr., Associate Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, and Steven Zucker

Additional resources:

American art at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

Ben Shahn

Ben Shahn, The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti

by DR. LARA KUYKENDALL

Ben Shahn: activist and artist

Ben Shahn said, “I hate injustice. I guess that’s about the only thing I really do hate.” Born in Lithuania (then part of the Russian Empire) in 1898, Shahn grew up in a family of leftist political activists. When Shahn was only four years old, his socialist father was exiled to Siberia because the Russian government suspected he was a revolutionary. Shahn remembered launching his own sort of protest as a child when he would shout “Down with the Czar!” at anyone wearing a uniform. As he recalled, “the air [in Russia] was filled with this whole revolutionary idea.”\(^{[1]}\)

In 1906, the whole family immigrated to New York and, like many fellow Eastern European Jews, settled in Brooklyn. As an adult, Shahn called himself “the most American of all American painters” because he “came to America and its culture and was sort of swallowing it by the cupful.”\(^{[2]}\) Apart from his love of baseball and chewing gum, Shahn’s Americanism lies in his Social Realist style. In that vein, he made paintings, prints, photographs, and drawings that address problems like racism, poverty, and oppression. His works are often critical of American life, but by exposing social problems, Shahn hoped to inspire reform.

The Sacco and Vanzetti case

One of Shahn’s most enduring subjects was prompted by the arrest, trial, and execution of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti. Sacco, a shoemaker, and Vanzetti, a fish seller, were accused of murdering two men during an armed robbery at a factory in Braintree, Massachusetts in 1920. After seven years of legal battles, Sacco and Vanzetti were executed just after midnight on August 23, 1927. Sacco and Vanzetti’s plight was a cause célèbre—a sensational case that captured the attention of millions of people around the world, many of whom protested against the convictions.

The case against Sacco and Vanzetti was troubled from the start by ethnic bigotry and political intolerance. Both men were Italian immigrants, drawn to the United States by the promise of freedom and democracy. But upon arrival, poverty and poor working conditions propelled them toward the radical communist and anarchist thinking of Luigi Galleani. The Galleanisti, as his followers were called, believed that capitalism was an evil economic system that disadvantaged workers to the point of desperation and that violence would be the most effective revolutionary strategy. Sacco and Vanzetti’s association with such a militant political group, along with their participation in labor strikes and evasion of the World War I military draft in 1917, placed them on the federal government’s watch list of dangerous subversives.

The trail of evidence that led police to arrest Sacco and Vanzetti for the Braintree murders was extraordinarily weak. Their fingerprints did not match those collected at the crime scene and the stolen money (over $15,000) was never found. Though both men owned guns, ballistic analysis never connected the bullets found at the crime scene with Sacco and Vanzetti’s weapons. Eyewitnesses to the murders did not credibly identify either suspect; in some cases, witnesses were coerced into giving false testimony. The prosecutor built on a general perception that Italians—especially Italian anarchists—were ruthless, murderous criminals bent on overthrowing the United States government. He argued that Sacco and Vanzetti appeared suspicious when arrested, that they lied during questioning, and the jury agreed and convicted them for the murders. Two men imprisoned for other offenses, Joe Morelli and Celestino Madeiros, later confessed to the Braintree crimes, but Sacco and Vanzetti’s prosecutors never followed up on their claims.

Outrage and irony in The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti

Shahn followed Sacco and Vanzetti’s case closely and believed, like many people around the world, that the two men were not given a fair trial. Shahn participated in protests in support of their release in the 1920s and made twenty-three images about the Sacco and Vanzetti affair in 1931 and 1932. Many of these, including the gouache Bartolomeo Vanzetti and Nicola Sacco (1931-32) were based on photographs that appeared in newspapers. He returned to the Sacco and Vanzetti case in drawings and prints in the 1950s and used The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti as part of the composition for a large mosaic at Syracuse University in 1967.

In Shahn’s early and iconic tempera-on-canvas painting, Sacco and Vanzetti lie in coffins in the foreground in front of a colonnaded neoclassical courthouse (image left). On the porch behind them hangs a portrait of the trial judge, Webster Thayer. Towering over Sacco and Vanzetti are the members of the committee that reviewed their convictions: Samuel Stratton, the president of MIT; Lawrence Lowell, Harvard’s president; and Robert Grant, a retired judge. These four men represent the wealthy, intellectual Massachusetts establishment, which was openly hostile to the radical ideals that Sacco and Vanzetti embodied.

Shahn used irony in this painting as a way of indicting Thayer, Stratton, Lowell, and Grant for the roles they played in Sacco and Vanzetti’s execution. In the background, Thayer raises his right hand as if he is taking an oath to uphold justice, but he faces a lamppost that resembles the bundle of sticks known as a fasces (image below). Once known as a symbol of judicial power, the fasces became a symbol for Italian fascism and oppression in the 1920s. Indeed, Thayer’s bias against immigrants and political radicals was widely known. He presided over Sacco and Vanzetti’s initial conviction and denied all motions for retrial. In response to public outcry, Lowell and his two cohorts were tasked with reviewing the proceedings and summarily upheld Sacco and Vanzetti’s convictions and death sentences after only ten days of deliberation.

Shahn explained in a 1944 interview, “Ever since I could remember I’d wished that I’d been lucky enough to be alive at a great time—when something big was going on, like the Crucifixion. And suddenly realized I was! Here I was living through another crucifixion. Here was something to paint!”\(^{[3]}\) The term “passion” in his title connects Sacco and Vanzetti’s deaths with Jesus’s martyrdom (the “Passion of Christ” refers to the period at the end of his life leading to the crucifixion). Shahn also painted in tempera, a matte medium that was used by Italian Renaissance artists for Christian panel paintings, but rarely by modernists in the twentieth century. His composition hearkens back to images of the Lamentation of Christ, but his mourning scene lacks the emotional force that typically accompanies Jesus’ death and burial. The three men in the foreground, Stratton, Lowell, and Grant, wear expressions that communicate placid resolve rather than sorrow. They seem uncomfortable and awkwardly crowded together in Shahn’s painting as they half-heartedly offer white lilies, symbols of goodness and purity, to the deceased. Here Shahn forces these men to bear witness to the injustice that they refused to prevent.

That Shahn’s The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti is eerily devoid of any kind of genuine, heartfelt anguish or grief amplifies the tragedy of the men’s deaths.

Shahn’s long career

Shahn’s career took off in the 1930s as his brand of realism resonated during the Great Depression when American audiences demanded that art communicate directly and serve a social purpose. Works like his photograph and painting of striking miners from Scotts Run, West Virginia (1935 and 1937) chronicled that decade’s challenges and contributed to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal efforts to use art to help the nation weather the crisis.

From the 1940s until his death in 1969, as Abstract Expressionism came to the fore in the United States, Shahn’s style evolved and his works became more symbolic, expressionistic, and even surreal. But he continually strove to portray dramatic, but universal human experiences like tragedy and survival in Liberation (1945), Age of Anxiety (1953), and the Lucky Dragon series (1960-62) with empathy and sincerity. The commitment to social justice that he established so clearly in The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti persisted throughout his career.

- Frances Pohl, Ben Shahn (Pomegranate Communications, 1993), p.12

Additional resources:

Alejandro Anreus, ed. Ben Shahn and The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti (Jersey City, NJ: The Jersey City Museum and Rutgers University Press, 2001.)

Susan Chevlowe, Common Man, Mythic Vision: The Paintings of Ben Shahn *Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998).

Morse, John. “Ben Shahn: An Interview,” Magazine of Art 37, no. 4 (April 1944), pp. 138-139.

Ben Shahn, Ben and Forrest Selvig, “Interview: Ben Shahn Talks with Forrest Selvig,” Archives of American Art Journal 17, no. 3 (1977), pp. 14-21.

The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti, 1967, mosaic, Syracuse University

Ben Shahn, Miners’ Wives

by JESSICA T. SMITH, PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{24}\): Ben Shahn, Miners’ Wives, c. 1948, tempera on panel, 121.9 x 91.4 cm (The Philadelphia Museum of Art) © Estate of Ben Shahn A conversation with Jessica T. Smith, Susan Gray Detweiler Curator of American Art, and Manager, Center for American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art and Dr. Beth Harris

Romare Bearden, Factory Workers

by DENNIS MICHAEL JON, MINNEAPOLIS INSTITUTE OF ART and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{25}\): Romare Bearden, Factory Workers, 1942, gouache and casein on brown Kraft paper mounted on board, 94.93 × 73.03 cm (Minneapolis Institute of Art)