9.4: Melanesia

- Page ID

- 67091

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Melanesia

This region includes the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, and the island of New Guinea, among many others.

c. 1500 B.C.E. - present

Melanesia, an introduction

To the north and east of Australia lie the islands known as Melanesia. These islands form one of the most culturally complex regions of the entire world, with 1,293 languages spoken across the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia and the island of New Guinea (politically divided into Indonesia’s West Papua Province and the nation of Papua New Guinea). It is also a region of great antiquity. New Guinea has been settled for around 45,000 years, the Solomon Islands for 35,000 years, and Vanuatu and New Caledonia for about 4,000.

Small scale societies

Throughout Melanesia, people lived in small scale societies often without strong leadership systems. Instead, communities were bound by ties of family and by complex networks of trade and exchange. Trade routes could link distant communities, and trading canoe voyages covered extensive distances. The daily round of food gardening, hunting, and in coastal areas, of fishing, were enriched by many rituals, often involving the production of remarkable objects such as the famous malangan carvings of New Ireland, and body decorations. In general Melanesians do not worship gods, but acknowledge the spirits and other beings sharing the landscape with them, and their ancestors.

European contact

Europeans first passed by these islands in the late sixteenth century, but sustained contact only began in the mid-nineteenth century. The British Museum collections date back to some of the earliest voyages in this later period of contact. The Museum continues to collect, adding objects which reflect the contemporary development of the three independent nations and two dependent colonies now in the region.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Ambum Stone

by DR. BILLIE LYTHBERG and DR. JANE HORAN

The Ambum Stone is a masterfully crafted stone carving, created around 3,500 years ago in the highlands of the island we now know as New Guinea. Who actually carved it and for what original purpose is not known. Nevertheless, the Ambum Stone had a life as a religious object for a group of people in Papua New Guinea before becoming an aesthetically beautiful and intriguing artifact of exotica in a Western gallery. More recently it suffered a mishap that left it broken, and the publicity around this thrust the Ambum Stone into ongoing political debates about who owns historical artifacts. Every chapter of this carving’s history has been entangled with personal and political intrigue, and chronicles a bigger story about colonization and shifting and evolving structures of power.

An ancient pestle

There are 12 recorded artifacts like the Ambum Stone: ancient stone mortars and pestles excavated from New Guinea, usually from the mountains of its interior. The smoothly curved neck and head of the Ambum Stone suggest its possible utility as a pestle when we consider its size—at about 8 inches high, the “neck” of the creature it depicts can be held in the hand, and its fat base could have been used to pound food and other materials. The tops of other ancient pestles from New Guinea are distinguished by human or bird heads, or by fully sculpted birds, while the mortars also include geometric imagery alongside avian (bird) and anthropomorphic (human) depictions.

The Ambum Stone is prized above all others not only for its age—it is one of the oldest of all sculptures made in Oceania—but also for its highly detailed sculptural qualities. It has a pleasing shape and smooth surface, and the slightly shiny patina on some of its raised details suggest it has been well handled. It was made from greywacke stone, and its finished shape may suggest the original shape the stone it was carved from. Greywacke is a very hard sedimentary stone, which often has fracture lines and veins that reveal its age and formation. Much greywacke has been subjected to significant amounts of tectonic movement, pressure and heat over extended periods, and some of the greywacke in the islands of the Pacific is more than 300 million years old. Imagine carving something as symmetrical and aesthetically pleasing as the Ambum Stone using only stone tools. It must have taken its maker many months to chip out the rough shape then finish it carefully, and the time and effort involved in its making suggests it was special and valued by whomever it was made for.

Carved in the form of some kind of animal, its features are rounded and include a freestanding neck, elegantly curved head and long nose, and upper limbs that hug its torso and appear to enclose a cupped space above its belly. Stylized eyes, ears and nostrils are depicted in relief, and shoulder blades and what could be an umbilicus suggest the maker’s understanding of anatomy. While it is possibly a fetal-form of a spiny anteater known as an echidna, which is thought to have been valued for its fat prior to the introduction of pigs, it might also be a bird or a fruit bat, and some have speculated that it represents a now extinct mega-sized marsupial.

Ritual use in Papua New Guinea

When the Ambum Stone first became known to Westerners in the 1960s, it was being used by a group of people called the Enga who live in the western highlands of Papua New Guinea. For the Enga, the Ambum Stone and other objects like it are called simting bilong tumbuna which literally translates as the “bones of the ancestors” (Egloff 2008:1). This is the Enga term for a class of cult objects which were used as powerful ritual mechanisms where ancestors reside. While the ritual object is not actually an ancestor per se, paradoxically, such sacred objects are believed to have a life of their own, and they can even move around, mate, and reproduce. It would seem—for the Ambum Stone at least—they can also go on adventures and create controversy.

Enga society is based on an organizational power structure known as the “big man” system, and the negotiation of power depends on commanding natural resources like pigs and produce, as well as supernatural forces like the goodwill of the ancestors (or the Christian God). Power is vested with those “big men” who can cajole, organize, or even manipulate other people into giving them resources so these can be redistributed at big ritual events. Before the Enga decided to convert to Christianity in the wake of the arrival of missionaries and colonization in the 1930s, the Ambum Stone and other objects like it were imbued with supernatural powers through ritual processes. They were buried in a group’s ancestral land and regular sacrifices of pigs were needed to appease the stones and the ancestors that resided in them. With the appropriate care they could ward off danger and promote the fertility and vigor of the tribe and the land.

Christianity, colonization, and commoditization

When Christian missionaries arrived in Papua New Guinea, people largely embraced the new religion, the new system of power that came with colonization, and the consequent Australian administration. The big man system was maintained but the way of managing the supernatural took on a Christian guise. Objects like the Ambum Stone lost some of their former potency, but under the “Whiteman’s gaze” they acquired new parameters of value as “primitive art” and were therefore worth money.

The Ambum Stone came to distil exoticism, imbued with all the romance perceived by Westerners in the stark differences of Papua New Guinean ways of seeing the world, and evoking a primitivism and purity lost to the West. This exoticism was enhanced by its specific dimensions and proportions that meet a certain aesthetic ideal from a Western point of view. All of this, its “primitive” and aesthetic value drove its pathway through a murky set of transactions, culminating in its acquisition by the Australian National Gallery in 1977, where it is valued as a priceless antiquity.

Originally sold by two young boys (at the urging of resident missionaries) for 20 shillings to the European owner of the trade store in Wabag (Enga Province), it was then sold by an intermediary to Philip Goldman, a London art dealer. Goldman subsequently offered it to the British Museum, before selling the sculpture to the Australian National Gallery in Canberra, Australia. In his negotiations with the Museum and by way of justifying his asking price, Goldman compared the Ambum Stone to Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles which the gallery had purchased a few years earlier: basing the “primitive” Ambum Stone’s value on that of a work of modern art. Eventually, the Australian National Gallery agreed to pay Goldman $115,000 United States dollars for the stone.

Protecting the cultural heritage of Papua New Guinea

The Papua New Guinea Museum attempted to buy the Ambum Stone when it was offered to the Australian Museum, but was unsuccessful. Papua New Guinea became an independent state in 1975, and robust legislation and other legal structures have been in place since 1913 that prohibit the export of objects of antiquity and relevance to Papua New Guinea as a unique place in the world. The country has not been able to afford to make purchases on the international antiquities market because prices are too high for a developing nation. Further, Papua New Guinea has not had the capacity to enforce its legislation internationally until recently. Whether the Ambum Stone was legally exported from Papua New Guinea remains a point of contention.

Many objects of New Guinea’s historical material culture were shipped to foreign museums and galleries for “safe keeping.” Other desirable or even potentially valuable objects were smuggled out illegally. In 1977, the legal standing of the Papua New Guinea state to reclaim objects of national significance was bolstered by the opening of the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery, complete with state of the art storage and exhibition facilities. It was staffed first by Europeans who in turn trained Papua New Guinea nationals in museum management who were politically and philosophically intent on having antiquities returned to Papua New Guinea. Over the years the Papua New Guinea Museum and Art Gallery has perfected its systems of export control and its capacity to enact legal proceedings against those intent on taking antiquities out of the country. They have also been able to successfully negotiate the return of objects and whole collections that were sequestered away for safe keeping elsewhere in the world. Nevertheless, there are limits to their ability to enforce the return of objects such as the Ambum Stone.

Damage and restoration

In 2000, while on loan to a French art museum, the Ambum Stone was accidentally dropped and shattered into three main pieces and various shards of stone. It was later discovered by conservators, as they pieced it back together, that what had previously been thought to be old breaks, mended while in Papua New Guinea, were actually fracture lines of the greywacke stone. Fissures and grooves containing organic material were examined and were used to suggest its date of 1500 B.C.E. The Ambum Stone was carefully repaired, but other damage had been done. News of the incident made it into international media, which in turn generated the discussion about what the Ambum Stone—a registered antiquity belonging to Papua New Guinea—was doing in the possession of an Australian gallery in the first place. Whilst the Ambum Stone remains in Canberra, arguably the controversy over this artifact has meant that Papua New Guinea’s capacity to negotiate at the global level has been bolstered.

At the heart of the recent chapters of the story of the Ambum Stone is a narrative about colonialism and its legacy. The Ambum Stone was made and imbued with particular meanings and values by a group of what we now know as Papua New Guineans, and then relocated to a Western museum where it has been reinterpreted within a framework of aesthetics and exchange, where we continue to marvel at it—and exoticize it—because of its origins, and the mysteries we perceive in the pages of its story, remain closed to us.

Other Resources

This sculpture at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Conservation and repair of the Ambum Stone (National Gallery of Australia, Canberra)

Egloff, Brian, Bones of the Ancestors – The Ambum Stone: from the New Guinea Higlands to the Antiquities Market to Australia (Lanham: Altamira Press, 2008).

Kjellgren, Eric, and Jennifer Wagelie, “Prehistoric Stone Sculpture from New Guinea,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mask (Buk), Torres Strait, Mabuiag Island

by DR. PERI KLEMM and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Mask (Buk), Torres Strait, Mabuiag Island, mid to late 19th century,turtle shell, wood, cassowary feathers, fiber, resin, shell, paint, 21 1/2 inches high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City)

Though we lack an understanding of its use or cultural context, this turtle-shell mask was certainly precious.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Presentation of Fijian Mats and Tapa Cloths to Queen Elizabeth II

A procession for a royal visit

On December 17, 1953, a newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II and her husband Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, arrived on the island of Fiji, then an English colony, and stayed for three days before continuing on their first tour of the commonwealth nations of England in the Pacific Islands. What is the Commonwealth of Nations?

The Commonwealth of Nations, today commonly known as the Commonwealth, but formerly the British Commonwealth, is an intergovernmental organization of 53 member states that were mostly territories of the former British Empire.

While the precise date of the photograph depicted above is unknown, there is still much that can be learned both about Fijian art and culture and the Queen’s historic visit. The first thing you might notice in the photograph is the procession of Fijian women making their way through a group of seated Fijian men and women.

Barkcloth

Several of the processing women are wearing skirts made of barkcloth painted with geometric patterns. Barkcloth, or masi, as it is referred to in Fiji, is made by stripping the inner bark of mulberry trees, soaking the bark, then beating it into strips of cloth that are glued together, often by a paste made of arrowroot. Bold and intricate geometric patterns in red, white, and black are often painted onto the masi. The practice of making masi continues in Fiji, where the cloth is often presented as gifts in important ceremonies such as weddings and funerals, or to commemorate significant events, such as a visit by the Queen of England. While in this photograph, the masi is only worn by the women and not carried, as far as can be ascertained in this picture; it is very likely that the women also presented the cloth to the Queen to celebrate the occasion of her visit.

Mats

What is definitely evident from the photograph are the rolls of woven mats that each woman in the procession carries. Like masi, Fijian mats served and continue to serve an important purpose in Fijian society as a type of ritual exchange and tribute. Made by women, Fijian mats are begun by stripping, boiling, drying, blackening, and then softening leaves from the Pandanus plant. The dried leaves are then woven into tight, often diagonal patterns that culminate in frayed or fringed edges.

While the mats that the women in this photograph are carrying may seem too plain to present to the Queen of England, their simplicity is an indication of their importance. In Fiji, the more simple the design, the more meaningful its function. Fijian artists continue to create mats and it is a practice that is growing, with many mats beings sold at market, often to tourists. With the advent of processed pandanus, they are more widely available than masi, and used heavily in wedding and funeral rituals.

In addition to masi and mats, Fijian art also includes elaborately carvings made of wood or ivory, as well as small woven god houses called bure kalou (left), which provided a pathway for the god to descend to the priest.

The Queen’s itinerary

Returning to the Queen’s visit in 1953, while in Fiji she visited hospitals and schools and held meetings with various Fijian politicians. She witnessed elaborate performances of traditional Fijian dances and songs and even participated in a kava ceremony, which was (and continues to be) an important aspect of Fijian culture. The kava drink is a kind of tea made from the kava root and is sipped by members of the community, in order of importance. On the occasion of the Queen’s visit, she was, as you might imagine, given the first sip of kava. In thinking about the importance of the kava ceremony, consider what might happen if everyone from a large group takes a sip from the same cup and of the same liquid. Although sipped in order of hierarchical importance, it would, in the end, put everyone in the group on the same level before beginning the event, meeting, or ceremony.

After three days on the island of Fiji, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip departed for the Kingdom of Tonga where they stayed for two days before leaving for extended stays in New Zealand and Australia. On Tonga, they were greeted warmly by Queen Sälote and other members of the royal Tongan family. On the occasion of her visit to Tonga, an enormous barkcloth was commissioned in Queen Elizabeth’s honor and had her initials, “ERIII,” painted onto the rare piece of ngatu. Referred to as ngatu launima in Tongan, it is just shy of 75 feet in length and is significant not only because it commemorated Queen Elizabeth’s visit, but also because it was placed under the coffin of Queen Sälote when her body was flown back to Tonga in 1960 after an extended stay in a New Zealand hospital. The barkcloth is now in the collection of Te Papa Tongarewa/Museum of New Zealand, after being donated by the pilot who had flown Queen Sälote’s body back to Tonga, to whom the barkcloth had been given by the Tongan Royal Family.

Additional resources:

This photograph in the National Library of New Zealand

Short film on Queen Elizabeth II’s visit to Fiji, December 1953

Short film on Queen Elizabeth II’s visit to Tonga, December 1953

Photographs of Queen Elizabeth II’s visit to Fiji, December 1953

Information on the barkcloth commissioned in Queen Elizabeth II’s honor

More information on barkcloth or tapa

Rod Ewins, Mat-Weaving in Gau, Fiji (Fiji Museum Special Publication, 1982).

———- Staying Fijian: Vatulele Island Barkcloth and Social Identity (Adelaide: Crawford House Publishing, 2006).

———- Traditional Fijian Artifacts (Nubeena, Tasmania: Just Pacific, 2014).

J.W. Sykes, The Royal Visit to the Colony of Fiji of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh (December 1953).

Bis Poles at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

by DR. MAIA NUKU and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Nine Bis Poles, from left to right: Jiem (artist), Otsjanep village, c. 1960; Jiem (artist), Otsjanep village, c. 1960; Terepos (artist), Omadesep village, c. 1960; Jewer (artist), Omadesep village, c. 1960; Fanipdas (artist), Omadesep village, c. 1960; artist unknown, probably Per village, c. 1960; artist unknown, Omadesep village, late 1950s; Ajowmien (artist), Omadesep village, c. 1960; Bifarq (artist), Otsjanep village, c. 1960, Asmat people, Faretsj River region, Papua Province, Irian Jaya, Indonesia, wood, paint, fiber (Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) Speakers: Dr. Maia Nuku, Evelyn A. J. Hall and John A. Friede Associate Curator for Oceanic Art and Dr. Steven Zucker

Master carvers produced statues like these when village leaders needed to bring their community back into balance.

Additional resources

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Life of Malagan

Let us assume this: that there is life in everything, and that living continues long after death. Certainly, we humans are alive; as are dogs, cats, lizards, fish, trees, and birds. But so too are rivers, forests, stones, boats, buildings, and even computers. All these lives and many more have one quality in common: they are relational beings. By that I mean they have the ability to interact with other living things and affect other lives in some way. Beyond anything else, it is through this ability to build relationships that we all remain alive in one form or another. From this basic premise, we can begin to understand the lives of malagan.

What are malagan?

The term malagan (also spelled malangan or malanggan) usually refers to one or more intricate carvings from the island of New Ireland in Papua New Guinea. These carvings may take the form of a mask, a wooden board or “frieze,” a sturdy housepole, a circular, woven mat, or a scaled model of a dugout canoe with or without human figures inside. In many such forms, malagan can be found in museums throughout the world. All of these well-traveled carvings were born in New Ireland, a place of extraordinary diversity. There alone, over thirty distinct languages are spoken. In most of these languages, the word malagan means “likeness,” or otherwise “to carve, or inscribe.”

To see a malagan in person or in a photograph is to meet many inscribed likenesses or motifs, each entwined to form a single, visible organism. Of these, there are several species: on mask-like malagan (referred to as Lentanon or Tantanua), we normally see a contrast in color and texture in hemispheric shapes above the face. Another, the Walik malagan, typically features two birds or two fish poised on opposite sides of the same hole, or “eye.” The Wowara malagan are characterized by a circular “sun” motif, and are typically woven from smooth, flat palm fronds. Upon seeing a malagan with its various motifs (examples in the images below), we might ask, what does it mean? Or otherwise, considering the careful detail that goes into them, we might question the tools and techniques utilized by master carvers in their production.

What do malagan do?

With such variation emerging from so many common motifs, malagan have confused and confounded anthropologists and art historians for over a century. Only recently have scholars begun to think differently about them. Rather than asking what each motif means, we are now listening more closely to the people of New Ireland and asking what each assemblage of motifs does in the world. By understanding these composite forms as agents, we can begin to see how malagan inspire, nurture, and participate in social life. To see this agency in action requires we look closely at the socioecological context out of which malagan come to life.

New Ireland

New Ireland is a narrow, tropical island only a few degrees south of the Equator. There are two primary seasons: a hot and dry period lasting from March to around November, and a rainy monsoon in December, January, and February. There are two modest towns on the island, but the majority of people live in rural villages. These indigenous residents spend the majority of their time in their beautiful gardens, where they grow sweet potatoes, cassava, bananas, various greens, and taro. In the village, they raise pigs, feeding them the white meat of dried coconuts. A significant part of their diet comes from the sea. They catch smaller fish on the coral reefs and larger fish like tuna and snapper in the deep ocean. While the fish can be caught year-round, the majority of garden food is harvested after the monsoon. Assuming the gardens are maintained properly (with labor as well as a kind of fertility magic), this seasonal variability yields a surplus of crops—far more than required for basic sustenance. This is fortunate, for the arrival of the dry season marks the time when large, elaborate feasts are held throughout the island to foster the passage of recently departed relatives into the afterlife.

Mortuary feasts

The people of New Ireland take these mortuary rituals very seriously. Throughout the year, as the crops grow larger and pigs grow fatter, the feasts are planned by the families of the deceased. Only when all the materials are ready—when enough pigs have been marked for sacrifice, enough taro has been dug out of the garden, and enough traditional shell-money (or mis) has been amassed—will the host family announce the impending event to the entire island. Malagan is the name given to these large mortuary feasts, but it more accurately refers to the carvings that are revealed with great flourish and excitement in the final moments of the event. At that time, hundreds or even thousands of people have gathered to witness a process of customary work led by an appointed cultural leader, or maimai. Dressed conspicuously in red, the maimai coordinates the entire event. He says when the pigs should be killed, when the taro should be peeled and roasted, and when various singsing groups should perform their unique song and dance. He supervises and coordinates obligatory exchange of mis (a traditional form of currency) and paper money between the family of the deceased and others who have supported them in their grief.

With bold chants and avian gestures, the maimai gathers everyone together for the grand revelation of one or more malagan carvings. It is his responsibility to ensure everyone witnesses the powerful malagan, pays for the experience of seeing it, and then consumes all of the prepared food before returning to their homes at sundown. This dramatic revelation brings the living malagan into the social world, but only for a brief moment. For many months prior to the final event, a skilled carver secludes himself in a special enclosure, well out of sight from those in the village. With seashells, stones, knives, sharks teeth, fire, and natural pigments, he inscribes into a piece of monsoon-borne driftwood a set of images that have come to him in a dream. Snakes, crocodiles, birds, fish, and other motifs are brought into relief, many of which hold a special association with a particular matriline.* Through the sweat and fire of his efforts, a powerful assemblage comes to life.

When it is finally revealed to the public, the malagan is considered “hot” and dangerous. Only when its witnesses “buy” it with mis, and when the feasting is complete, does its power diminish. The once-powerful malagan is cast aside to decay in the tropical forest, or is otherwise sold off to foreign tourists or museums. This final dismissal marks the “finishing” of the dead, when all the work of mourning and customary obligations has been settled. The dead are “sent away to biksolwara”—to the deep sea where everything has come from and to where everything eventually returns.

The power of the malagan

Like the maimai, the power or vitality of the malagan lies in its capacity to bring multiple clans together so that they may see each other, see themselves, and witness what the master carver has brought to life. Long after a dead receive their final malagan feast, part of that person remains active in the social world in the form of memory. Suppose, for example, a woman is working in the garden and sees a londoli (frigatebird) soaring overhead. There, for a brief moment, the graceful form of the bird prompts her to recall the intricate detail of malagan carved for her old uncle who died when she was only a child. That uncle, who long ago was sent away over the sea, enters back into her world through the power of that one particularly memorable motif. In this capacity, malagan and their associated mortuary rites ensure a vibrant social life for the people of New Ireland, and an eternal afterlife for their ancestors.

*Common throughout the Papua New Guinea islands, matriline refers to a descent group in which membership is inherited from one’s mother.

Additional resources:

New Ireland on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Malagan from the Google Cultural Institute

Malagan at the British Museum

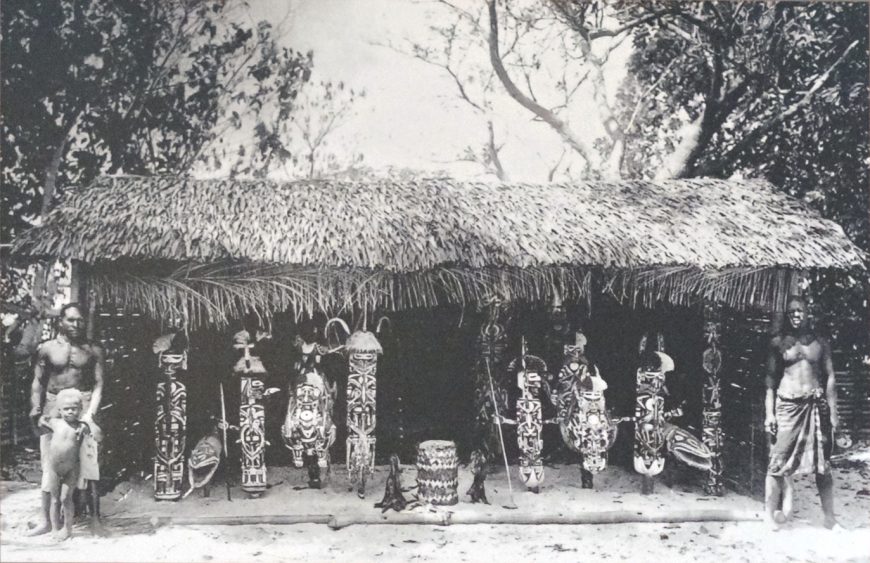

Malangan figure

This figure was made for malangan (also spelled malagan or malanggan), a cycle of rituals of the people of the north coast of New Ireland, an island in Papua New Guinea. Malangan express many complex religious and philosophical ideas. They are principally concerned with honoring and dismissing the dead, but they also act as affirmation of the identity of clan groups, and negotiate the transmission of rights to land. Malangan sculptures were made to be used on a single occasion and then destroyed. They are symbolic of many important subjects, including identity, kinship, gender, death, and the spirit world. They often include representations of fish and birds of identifiable species, alluding both to specific myths and the animal’s natural characteristics. For example, at the base of this figure is depicted a rock cod, a species which as it grows older changes gender from male to female. The rock cod features in an important myth of the founding of the first social group, or clan, in this area; thus the figure also alludes to the identity of that clan group.

This figure was collected by Hugh Hastings Romilly, Deputy Commissioner for the Western Pacific while he was on a tour of New Ireland in 1882-83. It was one a group of carvings made to be displayed at a particular malangan ritual. It is made of wood, vegetable fiber, pigment and shell (turbo petholatus opercula). They were originally standing in a carved canoe, which unfortunately Romilly did not collect. The whole group was presented to the British Museum by the Duke of Bedford in 1884, after Romilly had sent it to him.

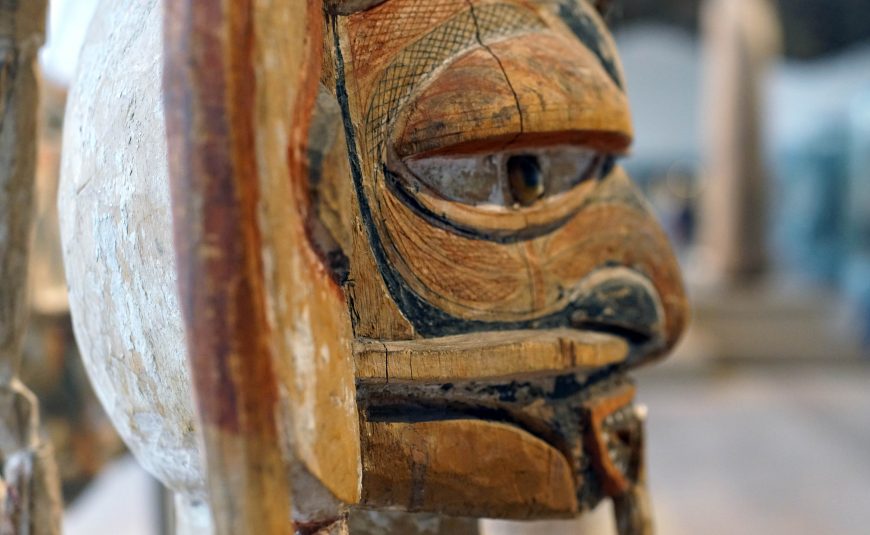

Malangan mask

Malangan masks are commonly used at funeral rites, which both bid farewell to the dead and celebrate the vibrancy of the living. The masks can represent a number of things: dead ancestors, ges (the spiritual double of an individual), or the various bush spirits associated with the area.

The ownership of Malangan objects is similar to the modern notion of copyright; when a piece is bought, the seller surrenders the right to use that particular Malangan style, the form in which it is made, and even the accompanying rites. This stimulates production, as more elaborate variations are made to replace the ones that have been sold.

Malangan ceremonies became extremely expensive affairs, taking into account the costs of the accompanying feasting. As a result, the funeral rites could take place months after a person had died. In some circumstances the ceremony would have been held for several people simultaneously.

Suggested readings:

L. Lincoln, An Assemblage of Spirits: Idea and Image in New Ireland (George Braziller, New York, in association with The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1987).

© The Trustees of the British Museum