9.3: Polynesia

- Page ID

- 67090

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Polynesia

Polynesia (which means "many islands") is one of the three major categories created by Westerners to refer to the islands of the South Pacific.

c. 1200 B.C.E. - present

Polynesia, an introduction

Oh Lono shake out a net-full of food,

A net-full of rain.

Gather them together for us.

Accumulate food, Oh Lono!

Collect fish, Oh Lono! (Hawaiian prayer to the God Lono)

Many islands

The islands of the eastern Pacific are known as Polynesia, from the Greek for “many islands.” Set within a triangle formed by Aotearoa (New Zealand) in the south, Hawaii to the north and Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in the east, the Polynesian islands are dotted across the vast eastern Pacific Ocean. Though small and separated by thousands of miles, they share similar environments and were settled by people with a common cultural heritage. The western Polynesian islands of Fiji and Tonga were settled approximately 3,000 years ago, whilst New Zealand was settled as recently as 1200 C.E.

These people were exceptional boat builders and sailed across the Pacific navigating by currents, stars and cloud formations. They were skilled fishermen and farmers, growing fruit trees and vegetables and raising pigs, chickens and dogs. Islanders were also accomplished craftspeople and worked in wood, fibre and feathers to create objects of power and beauty.

They were poets, musicians, dancers and orators. Eleven closely-linked languages were spoken across the region. They were so similar that Tupaia, a Tahitian who joined Captain Cook on his first voyage, was able to converse with islanders more than two thousand miles away in New Zealand.

Their societies were hierarchical, with the highest ranking people tracing their descent directly from the gods. These gods were all powerful and present in the world. Images of them were created in wood, feathers, fibre and stone. One of the most important items in the Museum’s collections is a carved wood figure of the Hawaiian god, Ku-ka’ilimoku, which stands over two and a half meters tall.

This large and intimidating figure was erected by King Kamehameha I, unifier of the Hawaiian islands at the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century. Kamehameha built a number of temples to his god, Ku-ka’ili-moku (‘Ku, the snatcher of land’), in the Kona district, Hawai’i, seeking the god’s support in his further military ambitions. The figure is likely to have been a subsidiary image in the most sacred part of one of these temples: not so much a representation of the god as a vehicle for the god to enter. Islanders grew fruit trees and used the wood to carve figures. This one depicts Ku, the “land snatcher.” The figure is characteristic of the god Ku, especially by his disrespectful open mouth, but his hair, incorporating stylized pigs’ heads, suggests an additional identification with the god Lono. The pigs’ heads are possibly symbolic of wealth.

Today, Polynesian culture continues to develop and change, partly in response to colonialism. Whilst traditional methods and techniques continue to be employed by skilled carvers and weavers, other artists have achieved international success in new media.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Voyage to the moai of Rapa Nui (Easter Island)

by DR. WAYNE NGATA and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Moai of Rapa Nui (Easter Island), Waka Tapu, and the reclaiming of cultural heritage

These giant statues embody the ancients who first voyaged to Rapa Nui. Many were toppled; all lost their coral eyes.

Easter Island Moai

The moai of Rapa Nui

Easter Island is famous for its stone statues of human figures, known as moai (meaning “statue”). The island is known to its inhabitants as Rapa Nui. The moai were probably carved to commemorate important ancestors and were made from around 1000 C.E. until the second half of the seventeenth century. Over a few hundred years the inhabitants of this remote island quarried, carved and erected around 887 moai. The size and complexity of the moai increased over time, and it is believed that Hoa Hakananai’a (below) dates to around 1200 C.E. It is one of only fourteen moai made from basalt, the rest are carved from the island’s softer volcanic tuff. With the adoption of Christianity in the 1860s, the remaining standing moai were toppled.

Their backs to the sea

This example was probably first displayed outside on a stone platform (ahu) on the sacred site of Orongo, before being moved into a stone house at the ritual center of Orongo. It would have stood with giant stone companions, their backs to the sea, keeping watch over the island. Its eyes sockets were originally inlaid with red stone and coral and the sculpture was painted with red and white designs, which were washed off when it was rafted to the ship, to be taken to Europe in 1869. It was collected by the crew of the English ship HMS Topaze, under the command of Richard Ashmore Powell, on their visit to Easter Island in 1868 to carry out surveying work. Islanders helped the crew to move the statue, which has been estimated to weigh around four tons. It was moved to the beach and then taken to the Topaze by raft.

The crew recorded the islanders’ name for the statue, which is thought to mean “stolen or hidden friend.” They also acquired another, smaller basalt statue, known asMoai Hava (left), which is also in the collections of the British Museum.

Hoa Hakananai’a is similar in appearance to a number of Easter Island moai. It has a heavy eyebrow ridge, elongated ears and oval nostrils. The clavicle is emphasized, and the nipples protrude. The arms are thin and lie tightly against the body; the hands are hardly indicated.

In the British Museum, the figure is set on a stone platform just over a meter high so that it towers above the visitor. It is carved out of dark grey basalt—a hard, dense, fine-grained volcanic rock. The surface of the rock is rough and pitted, and pinpricks of light sparkle as tiny crystals in the rock glint. Basalt is difficult to carve and unforgiving of errors. The sculpture was probably commissioned by a high status individual.

Hoa Hakananai’a’s head is slightly tilted back, as if scanning a distant horizon. He has a prominent eyebrow ridge shadowing the empty sockets of his eyes. The nose is long and straight, ending in large oval nostrils. The thin lips are set into a downward curve, giving the face a stern, uncompromising expression. A faint vertical line in low relief runs from the centre of the mouth to the chin. The jawline is well defined and massive, and the ears are long, beginning at the top of the head and ending with pendulous lobes.

The figure’s collarbone is emphasized by a curved indentation, and his chest is defined by carved lines that run downwards from the top of his arms and curve upwards onto the breast to end in the small protruding bumps of his nipples. The arms are held close against the side of the body, the hands rudimentary, carved in low relief.

Later carving on the back

The figure’s back is covered with ceremonial designs believed to have been added at a later date, some carved in low relief, others incised. These show images relating to the island’s birdman cult, which developed after about 1400 C.E. The key birdman cult ritual was an annual trial of strength and endurance, in which the chiefs and their followers competed. The victorious chief then represented the creator god, Makemake, for the following year.

Carved on the upper back and shoulders are two birdmen, facing each other. These have human hands and feet, and the head of a frigate bird. In the centre of the head is the carving of a small fledgling bird with an open beak. This is flanked by carvings of ceremonial dance paddles known as ‘ao, with faces carved into them. On the left ear is another ‘ao, and running from top to bottom of the right ear are four shapes like inverted ‘V’s representing the female vulva. These carvings are believed to have been added at a later date.

Collapse

Around 1500 C.E. the practice of constructing moai peaked, and from around 1600 C.E. statues began to be toppled, sporadically. The island’s fragile ecosystem had been pushed beyond what was sustainable. Over time only sea birds remained, nesting on safer offshore rocks and islands. As these changes occurred, so too did the Rapanui religion alter—to the birdman religion.

This sculpture bears witness to the loss of confidence in the efficacy of the ancestors after the deforestation and ecological collapse, and most recently a theory concerning the introduction of rats, which may have ultimately led to famine and conflict. After 1838 at a time of social collapse following European intervention, the remaining standing moai were toppled.

Suggested readings:

S.R. Fischer, “Rapani’s Tu’u ko Iho versus Mangareva’a ‘Atu Motua: Evidence for Multiple Reanalysis and Replacement in Rapanui Settlement Traditions, Easter Island,” Journal of Pacific History, 29 (1994), pp. 3–48.

S. Hooper, Pacific Encounters: Art and Divinity in Polynesia 1760-1860 (London, 2006).

A.L. Kaeppler, “Sculptures of Barkcloth and Wood from Rapa Nui: Continuities and Polynesian Affinities,” Anthropology and Aesthetics, 44 (2003), pp. 10–69.

R. Langdon, “New light on Easter Island Prehistory in a ‘Censored’ Spanish Report of 1770,” Journal of Pacific History, 30 (1995), pp. 112–120.

J.L. Palmer, “Observations on the Inhabitants and the Antiquaries of Easter Island,” Journal of the Ethnological Society of London, 1 (1869), pp. 371–377.

P. Rainbird, “A Message for our Future? The Papa Nui (Easter Island) Eco-disaster and Pacific Island Environments,” World Archaeology, 33 (2002), pp. 436–451.

J.A. Van Tilburg, and G. Lee, “Symbolic Stratigraphy, Rock Art and the Monolithic Statues of Easter Island,” World Archaeology, 19 (1987), pp. 133–149.

J.A. Van Tilburg, Remote Possibilities: Hoa Hakananai’a and HMS Topaze on Rapa Nui (London, 2006).

© Trustees of the British Museum

Paikea at the American Museum of Natural History

During the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century, the trade in ethnic artifacts was rife, particularly where territories had been colonized by European powers. Thousands of artifacts of all descriptions from across the Pacific were traded legally and illegally, and many now reside in museums, private collections, and other institutions throughout the world—including an important sculpture of a Māori ancestor named Paikea (pronounced pie-kee-ah)

The Whale Rider

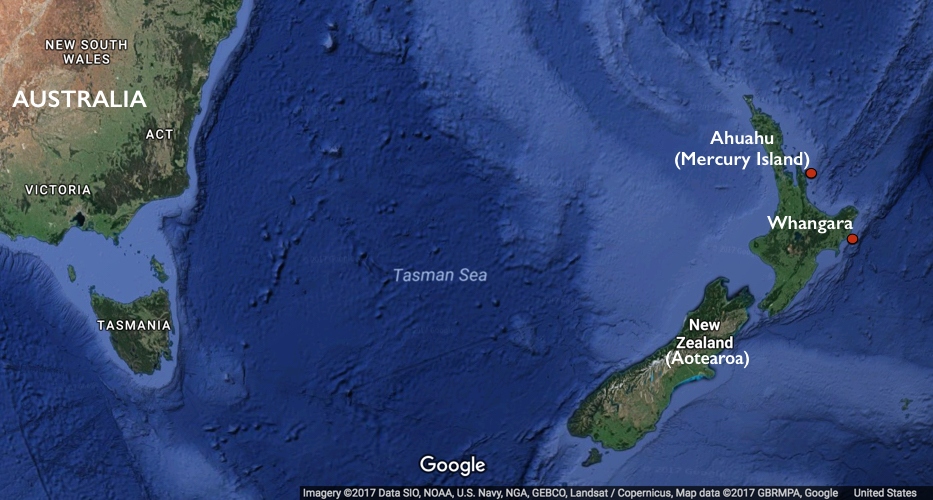

Paikea was an important ancestor of the Māori tribes in Uawa (Tolaga Bay) on the East Coast of the North Island of Aotearoa (New Zealand). He survived a marine disaster in the ancient Hawaiki homeland of the Māori in the Pacific Ocean, by invoking, through incantation, the denizens of the deep sea to come to his rescue and take him ashore. Paikea eventually made landfall at Ahuahu (Mercury Island) in Aotearoa (New Zealand). After several excursions to the south-east, Paikea eventually made his way to the mouth of the Waiapu River on the East Coast, married Huturangi, and settled at Whangara. He is more popularly known throughout the world as “The Whale Rider,” from the movie of the same name.

For his many descendants, Paikea is a key link to the ancient Hawaiki homeland, as well as to the marine stories and body of seafaring knowledge, and to the tribal settlements on the eastern seaboard of both islands of Aotearoa (New Zealand). He is honored through songs, genealogy, stories, dances, novels, film, and art.

A house and a dance

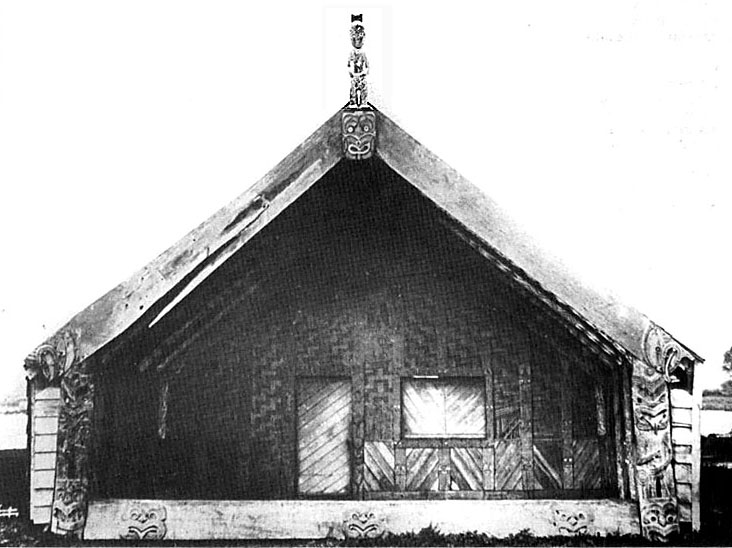

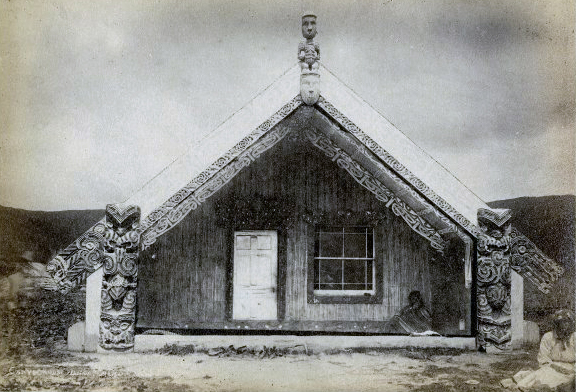

Paikea’s descedant, Te Kani a Takirau, was born 23 generations later, in about 1790. He was regarded throughout Māoridom as a leading ariki, a noble high-ranking person of his time. After Te Kani a Takirau’s death in 1856, a carved house was built by his people at Uawa, and named after him (see photograph at the top of the page). The carved figure on top was named Paikea, and notable orators composed a haka (posture dance) for this occasion:

| Uia mai koia whakahuatia ake | If it is asked |

| Ko wai te whare nei e? | What is the name of this house? |

| Ko Te Kani | It is Te Kani |

| Ko wai te tekoteko kei runga? | Who is the figurehead on top? |

| Ko Paikea, ko Paikea | It is Paikea, it is Paikea |

| Whakakau Paikea | Paikea transformed |

| Whakakau he tipua | Into an amazing being |

| Whakakau he taniwha | Into an awesome being |

| Ka ū Paikea ki Ahuahu, pakia! | And Paikea did come ashore at Ahuahu! |

| Kei te whitia koe ko Kahutiaterangi | Do not mistake him for Kahutiaterangi |

| E ai tō ure ki te tamahine a Te Whironui | He cohabited with the daughter of Te Whironui |

| Nāna i noho Te Rototahe | And resided at Te Rototahe |

| Auē, auē he koruru koe, e koro e! | You are there sire as the figurehead! |

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Since that time, six generations of Paikea’s descendants have performed this haka. For the past four generations it has also been performed as a waiata ā-ringa, an action song. In the last two generations it has developed into a novel—The Whale Rider, by Witi Ihimaera—which became the basis for the movie of the same name. This legacy now centers on another house: Whitireia at Whangara, on top of which Paikea sits on his whale. Children who are born into the legacy of Paikea “absorb” the haka and the waiata ā-ringa while growing up, performing it with peers, parents, and grandparents. It is a tribal marker, a rallying call, an expression of pride, and a reminder of our origins.

A century in storage

In 1908, the American Museum of Natural History acquired the Te Kani a Takirau Paikea from Major General Horatio Robley (British Army), a colonial collector of the time. Paikea was eventually placed on a storage shelf until 2013 when a small group of Paikea’s descendants of Te Aitanga a Hauiti, the tribe of Uawa, arranged a visit to the museum for the purpose of reconnecting with this ancestor figure—part of a bigger plan to reconstruct the house Te Kani a Takirau, physically or digitally.

It was an emotional visit: a mix of tearful reunion, immense pride and melancholy reflection. Coincidentally, the visit occurred at the same time as the Whales (Tohorā) exhibition at the museum, which allowed us to share our Paikea stories with members of the public, museum professionals, students, and others.

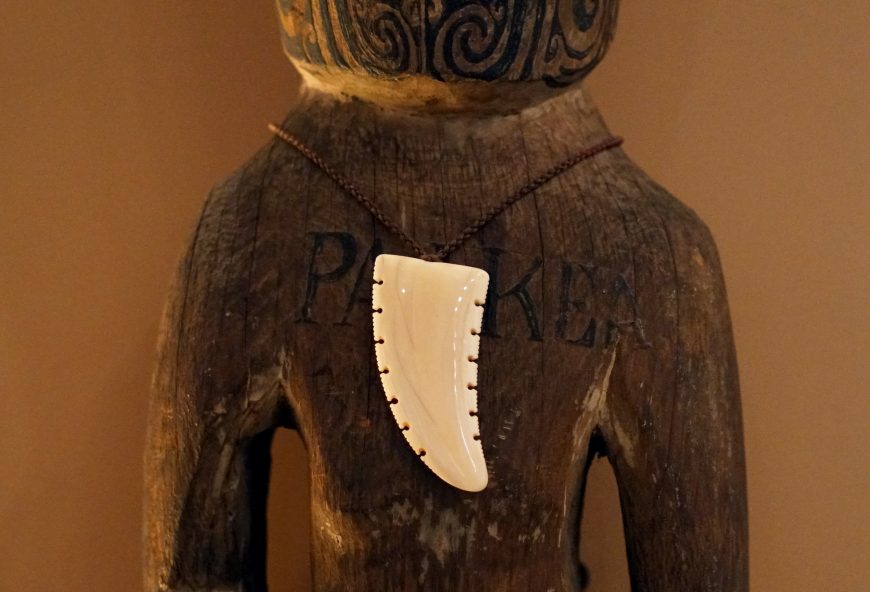

A token of love

Our parting with Paikea at the end of the week was difficult and tearful. As is our tradition, we left a gift with him as a token of our love: a carved whale tooth pendant sourced originally from a bull sperm whale that beached at Mahia in northern Hawkes Bay, New Zealand in 1967, which we secured around his neck. In doing so, we unknowingly transgressed museum acquisition protocols as well as international laws regarding trade in ivory, although we had done what was tika, or right, in our view. This provided an embarrassing conundrum for the museum curators who had hosted us, and so later that year the whale tooth was returned to us in New Zealand.

In 2017, as part of filming a documentary series “Artefact” and with the support of Greenstone TV, the American Museum of Natural History, and professional colleagues from Auckland University, we organized to return the whale tooth—legally this time—to Paikea, and make good our initial gift. Again, a small group of young people from Te Aitanga a Hauiti accompanied the whale tooth and once more the occasion, although shorter, was an emotional one. It was also an opportunity to consider repatriation again: both the process and the implications for the museum, and for Paikea’s descendants and their communities as well. This is what we will deliberate on over the next few months as we reflect on our experiences with this icon of our history and symbol of the colonial artifact trade.

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Additional resources:

Paikea at the American Museum of Natural History

Listen to a native speaker say “Maori”

Maori meeting house

Marae

The Maori built meeting houses before the period of contact with Europeans. The early structures appear to have been used as the homes of chiefs, though they were also used for accommodating guests. They did not exist in every community. From the middle of the nineteenth century, however, they started to develop into an important focal point of local society. Larger meeting houses were built, and they ceased to be used as homes. The open space in front of the house, known as a marae, is used as an assembly ground. They were, and still are, used for entertaining, for funerals, religious and political meetings. It is a focus of tribal pride and is treated with great respect.

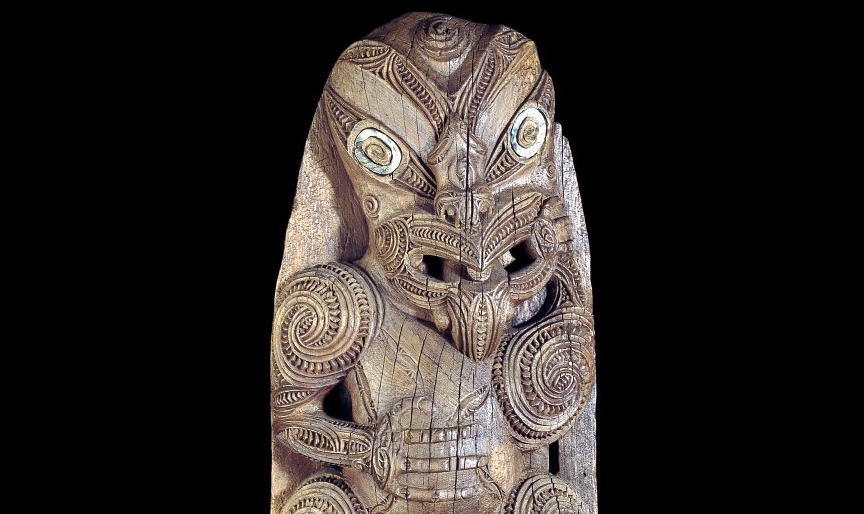

Pare

The meeting house is regarded as sacred. Some areas are held as more sacred than others, especially the front of the house. The lintel (pare) above the doorway is considered the most important carving, marking the passage from the domain of one god to that of another. Outside the meeting house is often referred to as the domain of Tumatauenga, the god of war, and thus of hostility and conflict. The calm and peaceful interior is the domain of Rongo, the god of agriculture and other peaceful pursuits.

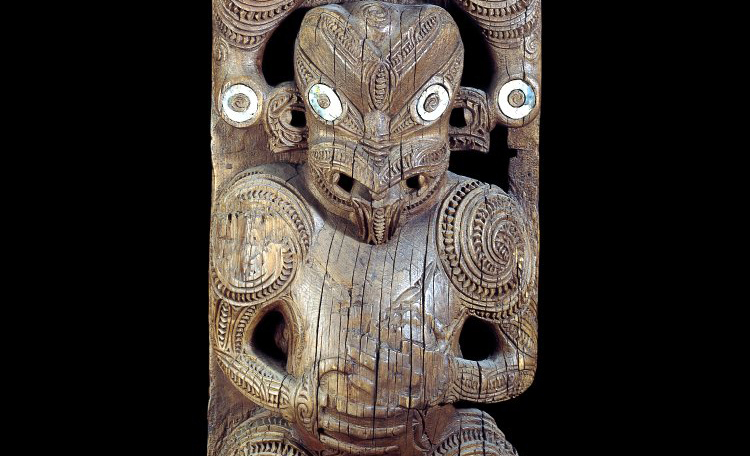

The example above illustrates one of the two main forms of door lintel. The three figures, with eyes inlaid with rings of haliotis shell, are standing on a base which symbolizes Papa or Earth. The scene refers to the moment of the creation of the world as the three figures push the sky god Rangi and earth apart. The three figures are Rangi and Papa’s children, the central one probably representing Tane, god of the forests. The two large spirals represent light and knowledge entering the world. The lintel was probably carved in the Whakatane district of the Bay of Plenty in the late 1840s.

Amo

This is a side post or amo from the front of a meeting house. A pair of amo would have supported the sloping barge boards of the house. The two carved figures represent named ancestors of the tribal group who owned the meeting house. The figures are male but the phalluses have been removed, probably after they were collected. Their eyes are inlaid with rings of haliotis shell. They are carved in relief with rauponga patterns, a style of Maori carved decoration in which a notched ridge is bordered by parallel plain ridges and grooves. Roger Neich, an expert on the subject of Maori carving, has identified the style of the carving of the post as that of the district of Poverty Bay in the East Coast area of the North Island.

This is one of a group of seven carvings purchased from Lady Sudeley in 1894. They were collected in New Zealand by her uncle, the Hon. Algernon Tollemache, probably between 1850 and 1873. This board and another from the same collection form a pair.

Poutokomanawa figure

This male figure is from the base of a poutokomanawa, an internal central post which supports the ridge-pole of a Maori meeting house. It represents an important ancestor of the tribal group which owned that house. The figure has fairly naturalistic features. It is clearly male, and has the typical Maori male hair topknot and a fully tattooed face. The eyes are inlaid with haliotis shell. The collar bone is carved as a raised ridge. The large hands have just three fingers each. This is not unusual, varying numbers of fingers are to be found on Maori carvings, and may be due to regional differences in style, rather than having a symbolic meaning.

The style of carving – the solidly proportioned body and large hands—is typical of the prominent Ngati Kahungunu school of carvers from the central Hawkes Bay district, in the mid-nineteenth century. The majority of Maori carving from this period is more stylized than this figure. This naturalistic style may have been intended to emphasize the social or human side of the ancestor represented.

The Maori meeting house increased in size and height during the nineteenth century, due partly to European influence. Consequently poutokomanawa figures increased in size until the largest were around two meters high.

Suggested readings:

J.C.H. King (ed.), Human Image (London, The British Museum Press, 2000).

D.R. Simmons, te whare runanga: the Maori me (Auckland, Reed Books, 1997).

D.C. Starzecka (ed.), Maori Art and Culture, 2nd ed. (London, The British Museum Press, 1998).

N. Thomas, Oceanic Art (London, Thames and Hudson, 1995).

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Rurutu figure known as A’a

A presentation to missionaries

In August 1821, a group of people from Rurutu in the Austral Islands, in the south-eastern Pacific Ocean, traveled north to the island of Ra’iatea in the Society Islands, to a London Missionary Society station. There, they presented to the missionaries a number of carved figures that represented their gods, as a symbol of their acceptance of Christianity. The population of Rurutu had all converted to Christianity in obedience to a decision made by their highest leaders. This figure was among those presented, and is described by one of the missionaries at the time, John Williams. It was taken into the London Missionary Society collections, brought to London in 1822, and subsequently sold to The British Museum in 1911.

There is debate about which of the Rurutu gods this figure represents. John Williams identifies it as A’a. The god is depicted in the process of creating other gods and men: his creations cover the surface of his body as thirty small figures.

The figure itself is hollow; a removable panel on its back reveals a cavity which originally contained twenty-four small figures. These were removed and destroyed in 1882. Contemporary Rurutuans explain that the exterior figures correspond to the kinship groups that make up their society, and propose a number of theories about the relationship between the figure and Christianity. It is carved from hardwood, probably from pua (Fagraea).

“There is a Supreme God in the ethnological section”

Since it came to London the figure has attracted considerable attention, and it is widely regarded as one of the finest pieces of Polynesian sculpture still in existence. It influenced the sculptor Henry Moore, and is also the subject of a poem by William Empson (1906-84), “Homage to the British Museum,” quoted below:

There is a Supreme God in the ethnological section;

A hollow toad shape, faced with a blank shield.

He needs his belly to include the Pantheon,

Which is inserted through a hole behind.

At the navel, at the points formally stressed, at the organs of sense,

Lice glue themselves, doll, local deities,

His smooth wood creeps with all the creeds of the world.Attending there let us absorb the culture of nations

And dissolve into our judgement all their codes.

Then, being clogged with a natural hesitation

(People are continually asking one on the way out),

Let us stand here and admit that we have no road.

Being everything, let us admit that is to be something,

Or give ourselves the benefit of the doubt;

Let us offer our pinch of dust all to this God,

And grant his reign over the entire building.

Recommended readings

J. Harding, “A Polynesian god and the missionaries,” Tribal Arts (Winter 1994), pp. 27-32.

A. Gell, Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1998).

W.B. Fagg, Tribal Image: Wooden Figure Sculpture of the World (London, The British Museum Press, 1970).

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Fly Whisk (Tahiri), Austral Islands

by DR. MAIA NUKU and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Fly Whisk (Tahiri), Austral Islands, early to mid-19th century, wood, fiber, and human hair, 13 x 81.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.206.1487). Speakers: Dr. Maia Nuku, Evelyn A. J. Hall and John A. Friede Associate Curator for Oceanic Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Dr. Steven Zucker

Ignore the Western name—spinning this object opened a channel of communication between ancestral and human realms.

Additional resources:

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Oceania on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Necklace (Lei Niho Palaoa), Hawai’i

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. MAIA NUKU

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Necklace (Lei Niho Palaoa), Hawai’i, early to mid-19th century, ivory, human hair, fiber, 4 1/4 x 16 in. / 10.8 x 40.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.206.1623). Speakers: Dr. Maia Nuku, Evelyn A. J. Hall and John A. Friede Associate Curator for Oceanic Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Dr. Beth Harris.

This spectacular necklace pairs human hair with a sperm-whale tooth. Chiefs wore it to assert their divine right.

Additional resources:

This work at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Oceania on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Feather cape

For ceremonies and battle

The Hawaiian male nobility wore feather cloaks and capes for ceremonies and battle. Such cloaks and capes were called ‘ahu’ula, or “red garments.” Across Polynesia the color red was associated with both gods and chiefs. In the Hawaiian Islands, however, yellow feathers became equally valuable, due to their scarcity. They consisted of olona (Touchardia latifolia) fibre netting made in straight rows, with pieces joined and cut to form the desired shape. Tiny bundles of feathers were attached to the netting in overlapping rows starting at the lower edge. The exterior of this example is covered with red feathers from the ‘i’iwi bird (Vestiaria cocchinea), yellow feathers from the ‘o’o (Moho nobilis), and black feathers also from the ‘o’o.

This small cape has a shaped neckline which would closely fit the wearer. This style of semi-circular cape is considered a later development from the trapezoidal shape. Large numbers of feathered cloaks and capes were given as gifts to the sea captains and their crews who were the earliest European visitors to Hawaii. Some of these attractive items would then have passed into the hands of the wealthy patrons who financed their voyages. It is not known who brought this particular cape to England.

Suggested readings:

P.H. Buck, Arts and crafts of Hawaii (Honolulu, Bishop Museum Press, 1957).

S. Phelps, Art and artifacts of the Pacific (London, Hutchinson, 1976).

© Trustees of the British Museum

Hiapo (tapa)

Polynesian history and culture

Polynesia is one of the three major categories created by Westerners to refer to the islands of the South Pacific. Polynesia means literally “many islands.” Our knowledge of ancient Polynesian culture derives from ethnographic journals, missionary records, archaeology, linguistics, and oral traditions. Polynesians represent vital art-producing cultures in the present day.

Each Polynesian culture is unique, yet the peoples share some common traits. Polynesians share common origins as Austronesian speakers (Austronesian is a family of languages). The first known inhabitants of this region are called the Lapita peoples. Polynesians were distinguished by long-distance navigation skills and two-way voyages on outrigger canoes. Native social structures were typically organized around highly developed aristocracies, and beliefs in primo-geniture (priority of the first-born). At the top of the social structure were divinely sanctioned chiefs, nobility, and priests. Artists were part of a priestly class, followed in rank by warriors and commoners.

Polynesian cultures value genealogical depth, tracing one’s lineage back to the gods. Oral traditions recorded the importance of genealogical distinction, or recollections of the accomplishments of the ancestors. Cultures held firm to the belief in mana, a supernatural power associated with high rank, divinity, maintenance of social order and social reproduction, as well as an abundance of water and fertility of the land. Mana was held to be so powerful that rules or taboos were necessary to regulate it in ritual and society. For example, an uninitiated person of low rank would never enter in a sacred enclosure without risking death. Mana was believed to be concentrated in certain parts of the body and could accumulate in objects, such as hair, bones, rocks, whale’s teeth, and textiles.

Gender roles in the arts

Gender roles were clearly defined in traditional Polynesian societies. Gender played a major role, dictating women’s access to training, tools, and materials in the arts. For example, men’s arts were often made of hard materials, such as wood, stone, or bone and men’s arts were traditionally associated with the sacred realm of rites and ritual.

Women’s arts historically utilized soft materials, particularly fibers used to make mats and bark cloth. Women’s arts included ephemeral materials such as flowers and leaves. Cloth made of bark is generically known as tapa across Polynesia, although terminology, decorations, dyes, and designs vary through out the islands.

Bark cloth as women’s art

Generally, to make bark cloth, a woman would harvest the inner bark of the paper mulberry (a flowering tree). The inner bark is then pounded flat, with a wooden beater or ike, on an anvil, usually made of wood. In Eastern Polynesia (Hawai’i), bark cloth was created with a felting technique and designs were pounded into the cloth with a carved beater. In Samoa, designs were sometimes stained or rubbed on with wooden or fiber design tablets. In Hawai’i patterns could be applied with stamps made out of bamboo, whereas stencils of banana leaves or other suitable materials were used in Fiji. Bark cloth can also be undecorated, hand decorated, or smoked as is seen in Fiji. Design illustrations involved geometric motifs in an overall ordered and abstract patterns.

The most important traditional uses for tapa were for clothing, bedding and wall hangings. Textiles were often specially prepared and decorated for people of rank. Tapa was ceremonially displayed on special occasions, such as birthdays and weddings. In sacred contexts, tapa was used to wrap images of deities. Even today, at times of death, bark cloth may be integral part of funeral and burial rites.

In Polynesia, textiles are considered women’s wealth. In social settings, bark cloth and mats participate in reciprocity patterns of cultural exchange. Women may present textiles as offerings in exchange for work, food, or to mark special occasions. For example, in contemporary contexts in Tonga, huge lengths of bark cloth are publically displayed and ceremoniously exchanged to mark special occasions. Today, western fabric has also been assimilated into exchange practices. In rare instances, textiles may even accumulate their own histories of ownership and exchange.

Hiapo: Niuean bark cloth

Niue is an island country south of Samoa. Little is known about early Niuean bark cloth or hiapo, as represented by the illustration depicted below. Niueans’ first contact with the west was the arrival of Captain Cook, who reached the island in 1774. No visitors followed for decades, not until 1830, with the arrival of the London Missionary Society. The missionaries brought with them Samoan missionaries, who are believed to have introduced bark cloth to Niue from Samoa. The earliest examples of hiapo were collected by missionaries and date to the second half of the nineteenth century. Niuean ponchos (tiputa) collected during this era, are based on a style that had previously been introduced to Samoa and Tahiti (see example at left). It is probable, however, that Niueans had a native tradition of bark cloth prior to contact with the West.

In the 1880s, a distinctive style of hiapo decorations emerged that incorporated fine lines and new motifs. Hiapo from this period are illustrated with complicated and detailed geometric designs. The patterns were composed of spirals, concentric circles, squares, triangles, and diminishing motifs (the design motifs decrease in size from the border to the center of the textile). Niueans created naturalistic motifs and were the first Polynesians to introduce depictions of human figures into their bark cloth. Some hiapo examples include writing, usually names, along the edges of the overall design.

Niuan hiapo stopped being produced in the late nineteenth century. Today, the art form has a unique place in history and serves to inspire contemporary Polynesian artists. A well-known example is Niuean artist John Pule, who creates art of mixed media inspired by traditional hiapo design.

Tapa today

Tapa traditions were regionally unique and historically widespread throughout the Polynesian Islands. Eastern Polynesia did not experience a continuous tradition of tapa production, however, the art form is still produced today, particularly in the Hawaiian and the Marquesas Islands. In contrast, Western Polynesia has experienced a continuous tradition of tapa production. Today, bark cloth participates in native patterns of celebration, reciprocity and exchange, as well as in new cultural contexts where it inspires new audiences, artists, and art forms.

Additional resources:

The Hiapo (tapa) from Niue in the Aukland War Memorial Museum

Work by John Pule in the Google Art Project

Bark cloth on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Polynesia, 1900 to the present on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Adrienne L Kaeppler, The Pacific Arts of Polynesia and Micronesia (Oxford History of Art: Oxford University Press, Oxford/New York, 2008).

Roger Neich and Mick Pendergrast, Traditional Tapa: Textiles of the Pacific (Thames and Hudson Ltd.: London, 1997).

Simon Kooijman, Polynesian Barkcloth (Shire Ethnography: Aylesbury, U.K., 1988).

John Pule and Nicolas Thomas, Hiapo Past and Present in Niuean Barkcloth (University of Otago Press: Dunnedin, Aotearoa/New Zeland, 2005).

Karen Stevenson, The Frangipani is Dead: Contemporary Pacific Art in New Zealand 1985-2000 (Wellington: Aotearoa/New Zealand, 2008).

Gottfried Lindauer, Tamati Waka Nene

Ancestor portraits

We all know portraits can be of ancestors, but can a portrait be an ancestor?

In Te Ao Māori, the Māori world, they can. Paintings like this one—and even photographs—do two important things. They record likenesses and bring ancestral presence into the world of the living. In other words, this portrait is not merely a representation of Tamati Waka Nene, it can be an embodiment of him. Portraits and other taonga tuku iho (treasures passed down from the ancestors) are treated with great care and reverence. After a person has died their portrait may be hung on the walls of family homes and in the wharenui (the central building of a community center), to be spoken to, wept over, and cherished by people with genealogical connections to them. Even when portraits like this one, kept in the collection of the Auckland Art Gallery, are absent from their families, the stories woven around them keep them alive and present. Auckland Art Gallery acknowledges these living links through its relationships with descendants of those whose portraits it cares for. The Gallery seeks their advice when asked for permission to reproduce such portraits. This portrait has been published in the Google Art Project, which is why we can look at it here.

Tamati Waka Nene

Māori are the indigenous people of New Zealand. The subject of this portrait, Tamati Waka Nene, was a Rangatira or chief of the Ngāti Hao people in Hokianga, of the Ngāpuhi iwi or tribe, and an important war leader. He was probably born in the 1780s, and died in 1871. He lived through a time of rapid change in New Zealand, when the first British missionaries and settlers were arriving and changing the Māori world forever. An astute leader and businessman, Nene exemplified the types of changes that were occurring when he converted to the Wesleyan faith and was baptised in 1839, choosing to be named Tamati Waka after Thomas Walker, who was an English merchant patron of the Church Missionary Society. He was revered throughout his life as a man with great mana or personal efficacy. What is Wesleyanism?

In his portrait, Nene wears a kahu kiwi, a fine cloak covered in kiwi feathers, and an earring of greenstone or pounamu. Both of these are prestigious taonga or treasures. He is holding a hand weapon known as a tewhatewha, which has feathers adorning its blade and a finely carved hand grip with an abalone or paua eye (image above). All of these mark him as man of mana or personal efficacy and status. But perhaps the most striking feature for an international audience is his intricate facial tattoo, called moko.

Gottfried Lindauer and his patron

Lindauer was a Czech artist who arrived in New Zealand in 1873 after a decade of painting professionally in Europe. He had studied at the Academy of Fine Art in Vienna from 1855 to 1861, and learned painting techniques rooted in Renaissance naturalism. When he left the Academy he began working as a portrait painter, and established his own portrait studio in 1864. Just ten years later he arrived in New Zealand and quickly became acquainted with a man called Henry Partridge who became his patron. Partridge commissioned Lindauer to paint portraits of well-known Māori, and three years later, in 1877, Lindauer held an exhibition in Wellington. The exhibition was important because it demonstrated Lindauer’s abilities and he was soon being commissioned by Māori chiefs to paint their portraits. Lindauer took different approaches to his commissions depending on who was paying. He tended to paint well-known Māori in Māori clothing for European purchasers, but painted unknown Māori in everyday European clothing when commissioned by their families to do so. His paintings are realistic, convincingly three-dimensional, and play beautifully with the contrast between light and shadow, causing his subjects to glow against their dark backgrounds. As his patron, Partridge amassed a large collection of portraits as well as large scale depictions that re-enacted Māori ways of life that were thought to be disappearing. In 1915, Partridge gave his collection of 62 portraits to the Auckland Art Gallery—the largest collection of Lindauer paintings in the world.

Painting Tamati Waka Nene

If you’ve been paying attention to dates you will have noticed that Nene died in 1871 but Lindauer didn’t arrive in New Zealand until 1873, and didn’t paint his portrait until 1890. It is likely that Lindauer based this portrait on a photograph taken by John Crombie, who had been commissioned to produce 12 photographic portraits of Māori chiefs for The London Illustrated News (image above). There are several other photographs of Nene, and in 1934 Charles F Goldie—another famous portrayer of Māori—painted yet another portrait of him from a photograph. So Nene didn’t sit for either of his famous painted portraits, but clearly sat for photographic portraits in the later years of his life. These were becoming more common by 1870, due to developments in photographic methods that made the whole process easier and cheaper. Many Māori had their portraits taken photographically and produced as a carte de visite, roughly the size of a playing card, and some had larger, postcard sized images made, called cabinet portraits. Lindauer is thought to have used a device called an epidiascope to enlarge and project small photographs such as these so he could paint them.

Lindauer didn’t make many sketches. He worked straight onto stretched canvas, outlining his subjects in pencil over a white background before applying translucent paints and glazes. Through the thinly painted surface of some of his works you can still see traces of pencil lines that may be evidence of his practice of outlining projected images. But Lindauer wasn’t simply copying photographs. In the 1870s, color photography had yet to be invented—Lindauer was working from black and white images and reimagining them in color. Moreover, sometimes he dressed his sitters—and those he painted from photos—in borrowed garments and adorned them with taonga that were not necessarily theirs. Thus some of his works contain artistic interventions rather than being entirely documentary.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Auckland Art Gallery

Behind the Brush—TV Documentary Series on Lindauer’s Māori portraits

Presentation of Fijian Mats and Tapa Cloths to Queen Elizabeth II

A procession for a royal visit

On December 17, 1953, a newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II and her husband Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, arrived on the island of Fiji, then an English colony, and stayed for three days before continuing on their first tour of the Commonwealth in the Pacific Islands.

The Commonwealth of Nations, today commonly known as the Commonwealth, but formerly the British Commonwealth, is an intergovernmental organization of 53 member states that were mostly territories of the former British Empire.

While the precise date of the photograph depicted above is unknown, there is still much that can be learned both about Fijian art and culture and the Queen’s historic visit. The first thing you might notice in the photograph is the procession of Fijian women making their way through a group of seated Fijian men and women.

Barkcloth

Several of the processing women are wearing skirts made of barkcloth painted with geometric patterns. Barkcloth, or masi, as it is referred to in Fiji, is made by stripping the inner bark of mulberry trees, soaking the bark, then beating it into strips of cloth that are glued together, often by a paste made of arrowroot. Bold and intricate geometric patterns in red, white, and black are often painted onto the masi. The practice of making masi continues in Fiji, where the cloth is often presented as gifts in important ceremonies such as weddings and funerals, or to commemorate significant events, such as a visit by the Queen of England. While in this photograph, the masi is only worn by the women and not carried, as far as can be ascertained in this picture; it is very likely that the women also presented the cloth to the Queen to celebrate the occasion of her visit.

Mats

What is definitely evident from the photograph are the rolls of woven mats that each woman in the procession carries. Like masi, Fijian mats served and continue to serve an important purpose in Fijian society as a type of ritual exchange and tribute. Made by women, Fijian mats are begun by stripping, boiling, drying, blackening, and then softening leaves from the Pandanus plant. The dried leaves are then woven into tight, often diagonal patterns that culminate in frayed or fringed edges.

While the mats that the women in this photograph are carrying may seem too plain to present to the Queen of England, their simplicity is an indication of their importance. In Fiji, the more simple the design, the more meaningful its function. Fijian artists continue to create mats and it is a practice that is growing, with many mats beings sold at market, often to tourists. With the advent of processed pandanus, they are more widely available than masi, and used heavily in wedding and funeral rituals.

In addition to masi and mats, Fijian art also includes elaborately carvings made of wood or ivory, as well as small woven god houses called bure kalou (left), which provided a pathway for the god to descend to the priest.

The Queen’s itinerary

Returning to the Queen’s visit in 1953, while in Fiji she visited hospitals and schools and held meetings with various Fijian politicians. She witnessed elaborate performances of traditional Fijian dances and songs and even participated in a kava ceremony, which was (and continues to be) an important aspect of Fijian culture. The kava drink is a kind of tea made from the kava root and is sipped by members of the community, in order of importance. On the occasion of the Queen’s visit, she was, as you might imagine, given the first sip of kava. In thinking about the importance of the kava ceremony, consider what might happen if everyone from a large group takes a sip from the same cup and of the same liquid. Although sipped in order of hierarchical importance, it would, in the end, put everyone in the group on the same level before beginning the event, meeting, or ceremony.

After three days on the island of Fiji, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip departed for the Kingdom of Tonga where they stayed for two days before leaving for extended stays in New Zealand and Australia. On Tonga, they were greeted warmly by Queen Sälote and other members of the royal Tongan family. On the occasion of her visit to Tonga, an enormous barkcloth was commissioned in Queen Elizabeth’s honor and had her initials, “ERIII,” painted onto the rare piece of ngatu. Referred to as ngatu launima in Tongan, it is just shy of 75 feet in length and is significant not only because it commemorated Queen Elizabeth’s visit, but also because it was placed under the coffin of Queen Sälote when her body was flown back to Tonga in 1960 after an extended stay in a New Zealand hospital. The barkcloth is now in the collection of Te Papa Tongarewa/Museum of New Zealand, after being donated by the pilot who had flown Queen Sälote’s body back to Tonga, to whom the barkcloth had been given by the Tongan Royal Family.

Additional resources:

This photograph in the National Library of New Zealand

Short film on Queen Elizabeth II’s visit to Fiji, December 1953

Short film on Queen Elizabeth II’s visit to Tonga, December 1953

Photographs of Queen Elizabeth II’s visit to Fiji, December 1953

Information on the barkcloth commissioned in Queen Elizabeth II’s honor

More information on barkcloth or tapa

Rod Ewins, Mat-Weaving in Gau, Fiji (Fiji Museum Special Publication, 1982).

———- Staying Fijian: Vatulele Island Barkcloth and Social Identity (Adelaide: Crawford House Publishing, 2006).

———- Traditional Fijian Artifacts (Nubeena, Tasmania: Just Pacific, 2014).

J.W. Sykes, The Royal Visit to the Colony of Fiji of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II and His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh (December 1953).

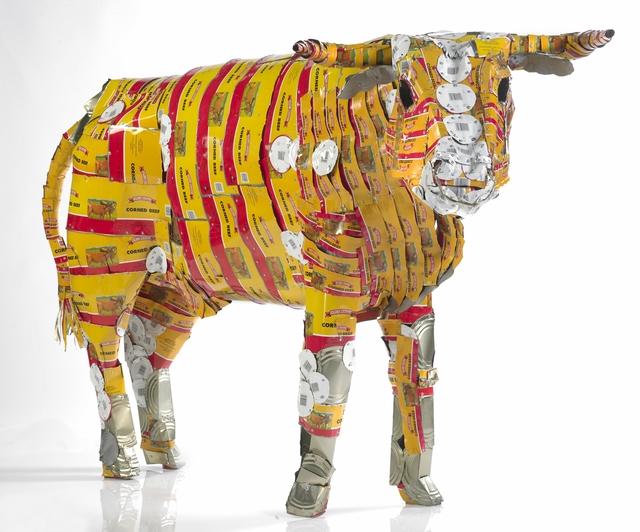

Michel Tuffery, Pisupo Lua Afe

What can a tin can bull teach us about ecological and population health issues in the Pacific? Michel Tuffery is one of New Zealand’s best-known artists of Pacific descent, with links to Samoa, Rarotonga and Tahiti. He majored in printmaking at Dunedin’s School of Fine Arts, and describes art quite literally as his first language because he didn’t read, write or speak until he was 6 years old. Encouraged instead to express himself through drawing, he now aims artworks like Pisupo Lua Afe primarily at children, hoping to engage their curiosity and inspire them to care for both their own health and that of the environment.

Pisupo Lua Afe is one of Tuffery’s most iconic works, made from hundreds of flattened corned beef tins, riveted together to form a series of life-sized bulls. Despite evident connections to Pop Art, especially Andy Warhol’s celebrations of the humble Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962), it’s impossible to read this work solely in the terms of Western art history. So what is Tuffery trying to tell us?

Pisupo—canned food in the Pacific

Pisupo is the Samoan language version of “pea soup,” which was the first canned food introduced into the Pacific Islands. Pisupo is now a generic term used to describe the many types of canned food that are eaten in the Islands—including corned beef. Not only is corned beef a favorite food source in the Islands, it has also become a ubiquitous part of the ceremonial gift economy. At weddings and birthdays, and other important life events both in the Islands and in Islander communities in New Zealand, gifts of treasured textiles like fine mats and decorated barkcloths are made alongside food items and cash money. But unlike the Island feast foods gifted at these events—such as pigs and large quantities of root vegetables—canned corned beef is a processed food high in saturated fat, salt and cholesterol (a type of fat that clogs arteries). These are all things that contribute to disproportionately high incidences of diabetes and heart disease in Pacific Island populations as diets formerly high in locally grown fruits and vegetables, seafood, coconut milk and flesh, give way to cheap, imported foodstuffs.

So Tuffery’s sculpture is impossible to separate from the ceremonies at which brightly colored tins of corned beef now figure in large quantities. But these links to traditional economic exchanges and population health only tell part of the story. Pisupo Lua Afe also critiques serious issues of ecological health and food sovereignty. Tuffery is interested in the introduction of cattle to New Zealand and the Pacific Islands and how they impact negatively on the plants, landscapes and waterways of these countries, as well as how industrialized approaches to farming disrupt traditional food production.

Look at Pisupo Lua Afe. It’s literally a “tinned bull”—solid, hard-edged and weighty. Whereas a real cow has a visual softness suggested by its movements, eyes and coat, Tuffery’s tin cans and rivets—overlapping like large metal scales— better convey the capacity of beef and dairy cattle to destroy fragile island eco-systems. Look closer—single out just one flattened can. Think about all the cans that were emptied to make Pisupo Lua Afe. Then think about all the cans that are emptied and discarded in the Pacific Islands each year. Tuffery is gesturing rather obviously towards the challenge of rubbish disposal in Island economies where creative “upcycling” of materials into new objects is often more common than the civic recycling regimes of larger cities and countries (upcycling refers to reusing discarded objects to create a product of a higher value). What use is there for thousands of empty tin cans? And what use are foods that cause ill health, damage the environment, and take up large swathes of land formerly used to grow healthier, indigenous foods? Especially when the Pacific Island nations under Tuffery’s scrutiny are recipients of some of the worst products of such agricultural farming: fatty lamb flaps and turkey tails, and tinned corned beef.

Food sovereignty

Food sovereignty (sometimes called food security) is a great lens through which to view the various threads of traditional economic exchanges, population health, environmental degradation and industrialized food production introduced so far. Food sovereignty is the right of a nation and its peoples to decide who controls how, where and by whom their food is to be produced, and what that food will be. For Indigenous peoples in the Pacific, food and the environment are sacred gifts. There cannot be food sovereignty without control over food production and ownership, and without appropriate care of the environment.

Alongside Pisupo Lua Afe and his other tin can bulls, Tuffery has produced many artworks that address challenges to food sovereignty and the continued exploitation of Pacific Island resources, including the taro leaf blight epidemic in Samoa in 1993, and drift net fishing that is depleting fish stocks. For example, he’s made fish tin sculptures, like his “tinned bull,” which upcycle cans that hold another “staple” food in the Pacific: tinned mackerel. Tuffery made two of these for an exhibition called Le Folauga, shown in Auckland, New Zealand in 2007, which are now in the collection of the Auckland War Memorial Museum.

In the exhibition’s catalogue he explained:

O le Saosao Lapo’a and Asiasi I reflect on the ironic and irreversible impact that over-fishing and exploitation of the Pacific’s natural resources has wrought on the traditional Pacific lifestyle. This includes changing virtually overnight the dietary habits of generations.

Is it co-incidental that significantly increasing health and dietary problems amongst Pacific Islanders has occurred during the same period that their premium fisheries catches are exported? And at the same time locals have experienced explosive growth of canned & other imported products flooding into the Pacific?

Tuffery states the aims of his works very clearly. His fish tin sculptures are perhaps even more interesting and evocative because they are also functional fish-smokers used to cure and preserve fish. They have been used in this way at his exhibition openings, bringing a smoky, wood- and fish-scented haze to the gallery experience.

Firebreathing bulls?

Tuffery has also brought his “tinned beef” bulls to smoky life in various performative installations throughout the world, by installing fireworks inside their heads to give them the appearance of breathing fire. Mounted on casters with their necks articulated so their heads can be turned, he has staged bullfights with his fire-breathing monsters, accompanied by drummers and groups of human performers issuing fierce challenges. But these performances have not been restricted to the sanctuary of the white-walled gallery—these were performed outdoors, on city streets, to reach a community that might not otherwise come into the gallery to encounter his work.

Additional resources:

This work at the Museum of New Zealand

Waking up the Objects—Michel Tuffery talks about his practice (video)

Tales from Te Papa: Pisupo Lua Afe Michel Tuffery’s fish tin sculptures (Le Folauga) (video)

Michel Tuffery and Patrice Kaikilekofe’s artist performance Povi tau vaga (The challenge) 1999

Issue-based Assemblage Sculpture: Pisupo lua afe (Corned Beef 2000), 1994 from the New Zealand Ministry of Education

Jennifer Hay, “Povi Christlike (Christchurch Bull) by Michael Tuffery”

More on Michael Tuffery from Tautai