8.2: Romanticism

- Page ID

- 67082

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Romanticism

In Romanticism, humanity confronted its fears and proclivity for violence.

c. 1800 - 1848

A beginner's guide

A beginner’s guide to Romanticism

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

19th century stylistic developments

As is fairly common with stylistic rubrics, the word “Romanticism” was not developed to describe the visual arts but was first used in relation to new literary and musical schools in the beginning of the 19th century. Art came under this heading only later. Think of the Romantic literature and musical compositions of the early 19th century: the poetry of Lord Byron, Percy Shelley, and William Wordsworth and the scores of Beethoven, Richard Strauss, and Chopin—these Romantic poets and musicians associated with visual artists. A good example of this is the friendship between composer and pianist Frederic Chopin and painter Eugene Delacroix. Romantic artists were concerned with the spectrum and intensity of human emotion.

Even if you do not regularly listen to classical music, you’ve heard plenty of music by these composers. In his epic film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, the late director Stanley Kubrick used Strauss’s Thus Spake Zarathustra (written in 1896, Strauss based his composition on Friedrich Nietzsche’s book of the same name, listen to it here). Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange similarly uses the sweeping ecstasy and drama of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, in this case to intensify the cinematic violence of the film.

Romantic music expressed the powerful drama of human emotion: anger and passion, but also quiet passages of pleasure and joy. So too, the French painter Eugene Delacroix and the Spanish artist Francisco Goya broke with the cool, cerebral idealism of David and Ingres’ Neo-Classicism. They sought instead to respond to the cataclysmic upheavals that characterized their era with line, color, and brushwork that was more physically direct, more emotionally expressive.

Additional resources:

Romanticism on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Romanticism as a literary movement from Mount Holyoke College

From NPR: The ‘Ode To Joy’ [Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony] As A Call To Action

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Orientalism

The origins of Orientalism

Snake charmers, carpet vendors, and veiled women may conjure up ideas of the Middle East, North Africa, and West Asia, but they are also partially indebted to Orientalist fantasies. To understand these images, we have to understand the concept of Orientalism, beginning with the word “Orient” itself. In its original medieval usage, the “Orient” referred to the “East,” but whose “East” did this Orient represent? East of where?

We understand now that this designation reflects a Western European view of the “East,” and not necessarily the views of the inhabitants of these areas. We also realize today that the label of the “Orient” hardly captures the wide swath of territory to which it originally referred: the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia. These are at once distinct, contrasting, and yet interconnected regions. Scholars often link visual examples of Orientalism alongside the Romantic literature and music of the early nineteenth century, a period of rising imperialism and tourism when Western artists traveled widely to the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia. We now understand that the world has been interconnected for much longer than we initially acknowledged and we can see elements of Orientalist representation much earlier—for example, in religious objects of the Crusades, or Gentile Bellini’s painting of the Ottoman sultan (ruler) Mehmed II (above), or in the arabesques (flowing s-shaped ornamental forms) of early modern textiles.

The politics of Orientalism

In his groundbreaking 1978 text Orientalism, the late cultural critic and theorist Edward Saïd argued that a dominant European political ideology created the notion of the Orient in order to subjugate and control it. Saïd explained that the concept embodied distinctions between “East” (the Orient) and “West” (the Occident) precisely so the “West” could control and authorize views of the “East.” For Saïd, this nexus of power and knowledge enabled the “West” to generalize and misrepresent North Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Though his text has itself received considerable criticism, the book nevertheless remains a pioneering intervention. Saïd continues to influence many disciplines of cultural study, including the history of art.

Representing the “Orient”

As art historian Linda Nochlin argued in her widely read essay, “The Imaginary Orient,” from 1983, the task of critical art history is to assess the power structures behind any work of art or artist.[1] Following Nochlin’s lead, art historians have questioned underlying power dynamics at play in the artistic representations of the “Orient,” many of them from the nineteenth century. In doing so, these scholars challenged not only the ways that the “West” represented the “East,” but they also complicate the long held misconception of a unidirectional westward influence. Similarly, these scholars questioned how artists have represented people of the Orient as passive or licentious subjects.

For example, in the painting The Snake Charmer and His Audience, c. 1879, the French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme’s depicts a naked youth holding a serpent as an older man plays the flute—charming both the snake and their audience. Gérôme constructs a scene out of his imagination, but he utilizes a highly refined and naturalistic style to suggest that he himself observed the scene. In doing so, Gérôme suggests such nudity was a regular and public occurrence in the “East.” In contrast, artists like Henriette Browne and Osman Hamdi Bey created works that provide a counter-narrative to the image of the “East” as passive, licentious or decrepit. In A Visit: Harem Interior, Constantinople, 1860, the French painter Browne represents women fully clothed in harem scenes. Likewise, the École des Beaux Arts-trained Ottoman painter Osman Hamdi Bey depicts Islamic scholarship and learnedness in A Young Emir Studying, 1878.

Orientalism: fact or fiction?

Orientalist paintings and other forms of material culture operate on two registers. First, they depict an “exotic” and therefore racialized, feminized, and often sexualized culture from a distant land. Second, they simultaneously claim to be a document, an authentic glimpse of a location and its inhabitants, as we see with Gérôme’s detailed and naturalistic style. In The Snake Charmer and His Audience, Gérôme constructs this layer of exotic “truth” by including illegible, faux-Arabic tilework in the background. Nochlin pointed out that many of Gérôme’s paintings worked to convince their audiences by carefully mimicking a “preexisting Oriental reality.”[2]

Surprisingly, the invention of photography in 1839 did little to contribute to a greater authenticity of painterly and photographic representations of the “Orient” by artists, Western military officials, technocrats, and travelers. Instead, photographs were frequently staged and embellished to appeal to the Western imagination. For instance, the French Bonfils family, in studio photographs, situated sitters in poses with handheld props against elaborate backdrops to create a fictitious world of the photographer’s making.

In Orientalist secular history paintings (narrative moments from history), Western artists portrayed disorderly and often violent battle scenes, creating a conception of an “Orient” that was rooted in incivility. The common figures and locations of Orientalist genre paintings (scenes of everyday life)—including the angry despot, licentious harem, chaotic medina, slave market, or the decadent palace—demonstrate a blend of pseudo-ethnography based on descriptions of first-hand observation and outright invention. These paintings created visions of a decaying mythic “East” inhabited by a controllable people without regard to geographic specificity. Artists operating in this vein include Jean-Léon Gérôme, Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and others. In the visual discourses of Orientalism, we must systematically question any claim to objectivity or authenticity.

Global imperialism and consumerism

We also must consider the creation of an “Orient” as a result of imperialism, industrial capitalism, mass consumption, tourism, and settler colonialism in the nineteenth century. In Europe, trends of cultural appropriation included a consumerist “taste” for materials and objects, like porcelain, textiles, fashion, and carpets, from the Middle East and Asia. For instance, Japonisme was a trend of Japanese-inspired decorative arts, as were Chinoiserie (Chinese-inspired) and Turquerie (Turkish-inspired). The ability of Europeans to purchase and own these materials, to some extent confirmed imperial influence in those areas.

The phenomenon of World’s Fairs and cultural-national pavilions (beginning with the Crystal Palace in London in 1851 and continuing into the twentieth century) also supported the goals of colonial expansion. Like the decorative arts, they fostered the notion of the “Orient” as an entity to be consumed through its varied pre-industrial craft traditions.

We see this continually in the architectural imitations built on the grounds of these fairs, that sought to provide both spectacle and authenticity to the fair goer. For instance, at the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris, the designers of the Egyptian section Jacques Drévet and E. Schmitz topped what was supposed to represent the residential khedival (Ottoman Empire ruler’s) palace with a dome typical of mosque architecture.[3] Yet, they also attached to this building a barn (not typical of a khedival palace) that housed imported donkeys brought in to give visitors the impression of reality.[4] The fairs objectified the otherness of non-Western peoples, cultures, and practices.

Orientalism constructs cultural, spatial, and visual mythologies and stereotypes that are often connected to the geopolitical ideologies of governments and institutions. The influence of these mythologies has impacted the formation of knowledge and the process of knowledge production. In this light, as Saïd and Nochlin remind us, when we see Orientalist works like Gérôme’s Snake Charmer, we should ask what idea of the “Orient” we see, and why?

- Linda Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient,” Art in America, vol. IXXI, no. 5 (1983), pp. 118–31.

- Ibid., 37.

- Zeynep Çelik, Displaying the Orient: Architecture of Islam at Nineteenth-Century World’s Fairs (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992).

- Timothy Mitchell, Colonizing Egypt, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991).

Additional resources:

Roger Benjamin, Orientalist Aesthetics: Art, Colonialism, and French North Africa 1880–1930 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003).

Zeynep Çelik, “Colonialism, Orientalism, and the Canon” The Art Bulletin 78, no. 2 (June 1996): pp. 202-205.

Zeynep Çelik, Displaying the Orient: Architecture of Islam at Nineteenth-Century World’s Fairs (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992).

Oleg Grabar, “Europe and the Orient: An Ideologically Charged Exhibition.” Muqarnas VII (1990): pp. 1-11.

Robert Irwin, Dangerous Knowledge: Orientalism and its Discontents (Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2006).

J.M. MacKenzie, Orientalism: History, Theory, and the Arts (Manchester, NY: Manchester University Press, 1995).

Linda Nochlin, “The Imaginary Orient,” A. America, IXXI/5 (1983): pp. 118–31.

Edward Saïd, Orientalism (New York: Vintage Books, 1978).

Edward Saïd, “Orientalism Reconsidered,” Race & Class 27, no. 2 (Autumn 1985): pp. 1-15.

Nicholas Tromans, ed. The Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting (London: Tate, 2008).

Stephen Vernoit and D. Behrens-Abouseif, eds. Islamic Art in the Nineteenth Century: Tradition, Innovation, and Eclecticism (Leiden; Boston: Brill Publishers, 2006).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Romanticism in France

“Romanticism lies neither in the subjects that an artist chooses nor in his exact copying of truth, but in the way he feels…."

—Charles Baudelaire

Romanticism in France

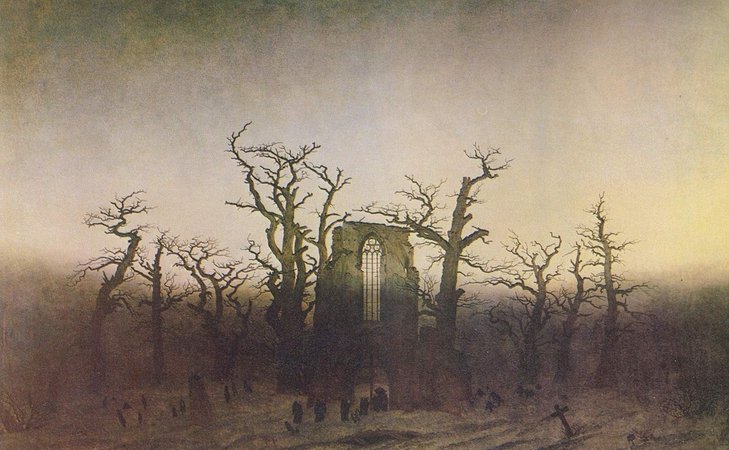

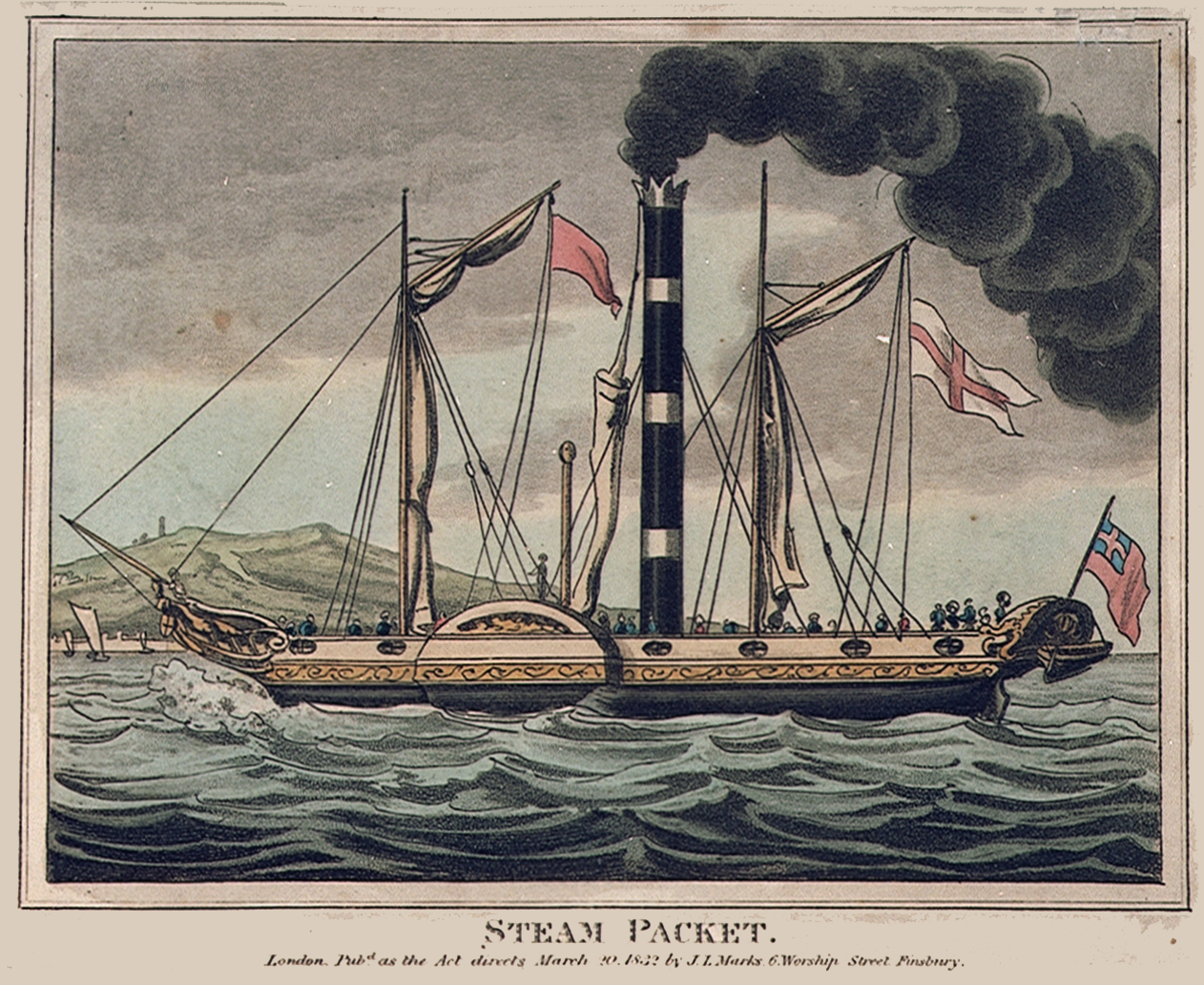

In the decades following the French Revolution and Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo (1815) a new movement called Romanticism began to flourish in France. If you read about Romanticism in general, you will find that it was a pan-European movement that had its roots in England in the mid-eighteenth century. Initially associated with literature and music, it was in part a response to the rationality of the Enlightenment and the transformation of everyday life brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Like most forms of Romantic art, nineteenth-century French Romanticism defies easy definitions. Artists explored diverse subjects and worked in varied styles so there is no single form of French Romanticism.

Intimacy, spirituality, color, yearning for the infinite

Even when Charles Baudelaire wrote about French Romanticism in the middle of the nineteenth century, he found it difficult to concretely define. Writing in his Salon of 1846, he affirmed that “romanticism lies neither in the subjects that an artist chooses nor in his exact copying of truth, but in the way he feels…. Romanticism and modern art are one and the same thing, in other words: intimacy, spirituality, color, yearning for the infinite, expressed by all the means the arts possess.”

One might trace the emergence of this new Romantic art to the painting of Jacques-Louis David who expressed passion and a very personal connection to his subject in Neoclassical paintings like Oath of the Horatii and Death of Marat. If David’s work reveals the Romantic impulse in French art early on, French Romanticism was more thoroughly developed later in the work of painters and sculptors such as Theodore Gericault, Eugène Delacroix and François Rude.

In 1810, Germaine de Staël introduced the new Romantic movement to France when she published Germany (De l’Allemagne). Her book explored the concept that while Italian art might draw from its roots in the rational, orderly Classical (ancient Greek and Roman) heritage of the Mediterranean, the northern European countries were quite different. She held that her native culture of Germany—and perhaps France—was not Classical but Gothic and therefore privileged emotion, spirituality, and naturalness over Classical reason. Another French writer Stendhal (Henri Beyle) had a different take on Romanticism. Like Baudelaire later in the century, Stendhal equated Romanticism with modernity. In 1817 he published his History of Painting in Italy and called for a modern art that would reflect the “turbulent passions” of the new century. The book influenced many younger artists in France and was so well-known that the conservative critic Étienne Jean Delécluze mockingly called it “the Koran of the so-called Romantic artists.”

The direct expression of the artist’s persona

The first marker of a French Romantic painting may be the facture, meaning the way the paint is handled or laid on to the canvas. Viewed as a means of making the presence of the artist’s thoughts and emotions apparent, French Romantic paintings are often characterized by loose, flowing brushstrokes and brilliant colors in a manner that was often equated with the painterly style of the Baroque artist Rubens. In sculpture artists often used exaggerated, almost operatic, poses and groupings that implied great emotion. This approach to art, interpreted as a direct expression of the artist’s persona—or “genius”—reflected the French Romantic emphasis on unregulated passions. The artists employed a widely varied group of subjects including the natural world, the irrational realm of instinct and emotion, the exotic world of the “Orient” and contemporary politics.

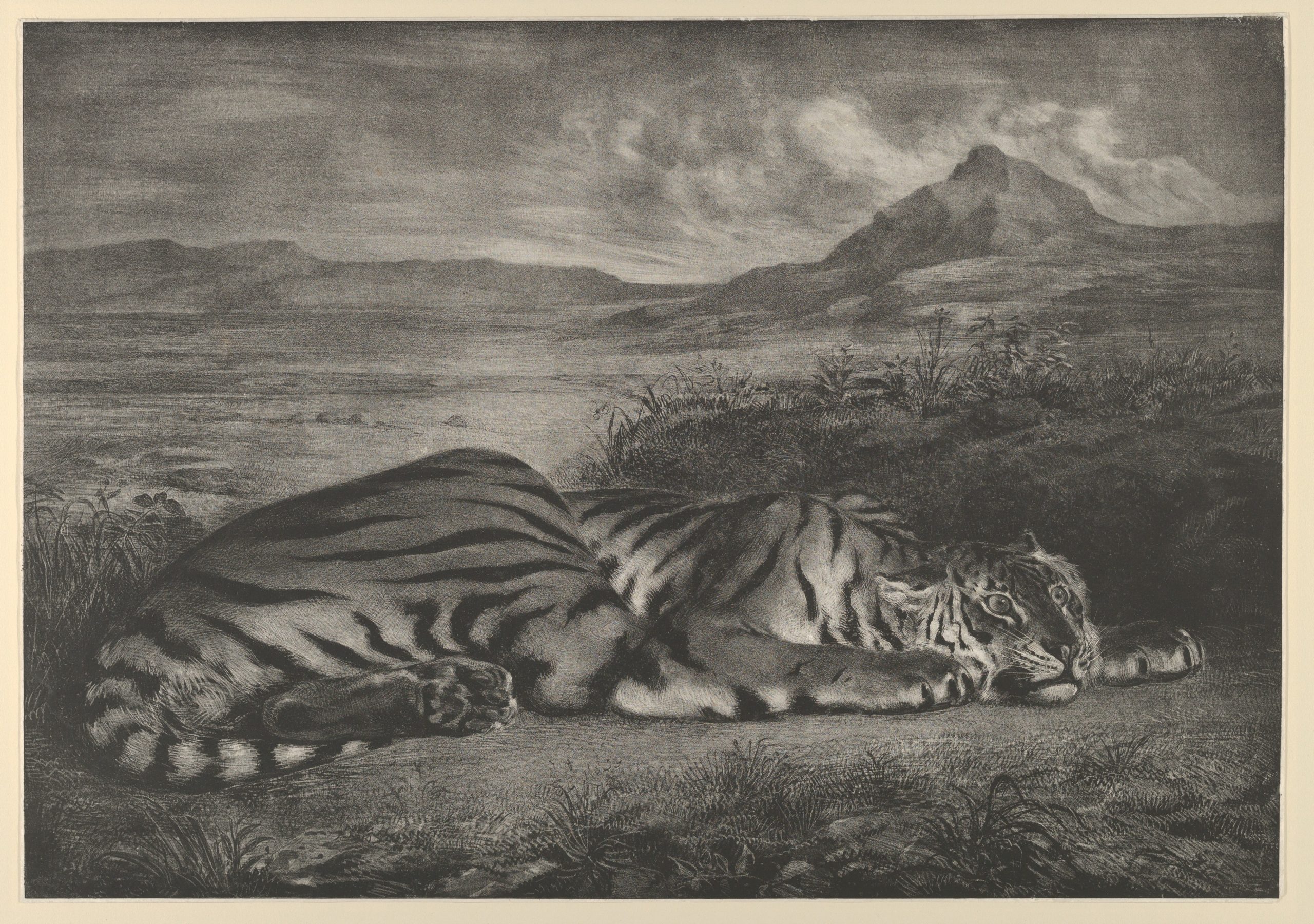

Man and nature

The theme of man and nature found its way into Romantic art across Europe. While often interpreted as a political painting, Théodore Géricault’s remarkable Raft of the Medusa (1819) confronted its audience with a scene of struggle against the sea. In the ultimate shipwreck scene, the veneer of civilization is stripped away as the victims fight to survive on the open sea. Some artists, including Gericault and Delacroix, depicted nature directly in their images of animals. For example, the animalier (animal sculptor) Antoine-Louis Barye brought the tension and drama of “nature red in tooth and claw” to the exhibition floor in Lion and Serpent (1835.)

Not solely reason, but also emotion and instinct

Another interest of Romantic artists and writers in many parts of Europe was the concept that people, like animals, were not solely rational beings but were governed by instinct and emotion. Gericault explored the condition of those with mental illness in his carefully observed portraits of the insane such as Portait of a Woman Suffering from Obsessive Envy (The Hyena), 1822. On other occasions artists would employ literature that explored extreme emotions and violence as the basis for their paintings, as Delacroix did in Death of Sardanapalus (1827-28.)

Eugène Delacroix, who once wrote in his diary “I dislike reasonable painting,” took up the English Romantic poet Lord Byron’s play Sardanapalus as the basis for his epic work Death of Sardanapalus (below) depicting an Assyrian ruler presiding over the murder of his concubines and destruction of his palace. Delacroix’s swirling composition reflected the Romantic artists’ fascination with the “Orient,” meaning North Africa and the Near East—a very exotic, foreign, Islamic world ruled by untamed desires. Curiously, Delacroix preferred to be called a Classicist and rejected the title of Romantic artist.

Whatever he thought of being called a Romantic artist, Delacroix brought his intense fervor to political subjects as well. Responding to the overthrow of the Bourbon rulers in 1830, Delacroix produced Liberty Leading the People (below, 1830). Brilliant colors and deep shadows punctuate the canvas as the powerful allegorical figure of Liberty surges forward over the hopeful and despairing figures at the barricade.

That intensity of emotion, so characteristic of French Romantic art, would be echoed if not amplified by the sculptor François Rude’s Departure of the Volunteers of 1792 (La Marseillaise) (1833-6). Its energetic winged figure of France/Liberty, a modern Nike, seems to scream out as she leads the native French forward to victory in one of the very few Romantic public monuments.

Today, French Romanticism remains difficult to define because it is so diverse. Baudelaire’s comments from the Salon of 1846 may still apply: “romanticism lies neither in the subjects that an artist chooses nor in his exact copying of truth, but in the way he feels.”

Additional resources:

Romanticism on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, Napoleon Bonaparte Visiting the Pest House in Jaffa

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, Napoleon Bonaparte Visiting the Pest House in Jaffa, 1804, oil on canvas, 209 x 280″ (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Gros was a student of the Neo-Classical painter Jacques-Louis David. However, this painting, sometimes also titled Napoleon Visiting the Pest House in Jaffa, is a proto-Romantic painting that points to the later style of Gericault and Delacroix. Gros was trained in David’s studio between 1785-1792, and is most well known for recording Napoleon’s military campaigns, which proved to be ideal subjects for exploring the exotic, violent, and heroic. In this painting, which measures more than 17 feet high and 23 feet wide, Gros depicted a legendary episode from Napoleon’s campaigns in Egypt (1798-1801).

On March 21, 1799, in a make-shift hospital in Jaffa, Napoleon visited his troops who were stricken with the Bubonic Plague. Gros depicts Napoleon attempting to calm the growing panic about contagion by fearlessly touching the sores of one of the plague victims. Like earlier neoclassical paintings such as David’s Death of Marat, Gros combines Christian iconography, in this case Christ healing the sick, with a contemporary subject. He also draws on the art of classical antiquity, by depicting Napoleon in the same position as the ancient Greek sculpture, the Apollo Belvedere. In this way, he imbues Napoleon with divine qualities while simultaneously showing him as a military hero. But in contrast to David, Gros uses warm, sensual colors and focuses on the dead and dying who occupy the foreground of the painting. We see the same approach later in Delacroix’s painting of Liberty Leading the People (1830).

Napoleon was a master at using art to manipulate his public image. In reality he had ordered the death of the prisoners whom he could not afford to house or feed, and poisoned his troops who were dying from the plague as he retreated from Jaffa.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Portrait of Madame Rivière

by BEN POLLITT

Not to Invent but to continue…

“Everything has been done before” Ingres once wrote. “Our task is not to invent but to continue what has already been achieved.” Hardly any wonder then, being so suspicious of innovation, that his work is often set against the more radical painting styles of his age.

The conflict between Ingres and Delacroix, master of the nouvelle école (new school), is the stuff of art historical legend; in one corner, Ingres the Neoclassicist, all finesse, the consummate draughtsman, upholding the primacy of line; in the other, Delacroix the Romantic, all passion, a master of the virtuosic brushstroke, whose work abounds with expressive color.

And yet, to polarize them in this way, does an injustice to both artists. Certainly, as this painting demonstrates, Ingres was more than capable of bending the rules of academic practice and as such perhaps has more in common with his great rival than one might at first suspect.

Wealth and status

The subject of the painting is Madame Philibert Rivière, the wife of a high-ranking government official in the Napoleonic Empire. Framed within an oval, the sitter reclines on a divan, her left arm resting on a velvet cushion. She looks out, her gaze meeting us, though obliquely, as if lost in her own thoughts. Comfortable with her beauty, surrounded by ample evidence of her wealth and high social standing, she does not need to seek our approval.

Her clothes signal her status. Dressed in a white satin dress, around her shoulder is draped a voluminous cashmere shawl which swirls rhythmically around her shoulders and right arm. Gold links shimmer on her neck and wrists. Even her carefully coifed raven black hair, bound in curls, as was the fashion, attests to her affluence, being held in place by the application of huile antique, an extremely expensive scented oil that only the rich could afford.

Textures

As with so many of his portraits, Ingres delights in capturing surface textures: the plush velvet; the crisp brightness of the silk, tanning the flesh; the twisted tassel of the cushion; the polished finish on the wood grain, all weave around and animate the figure. Note the way, for example, the shawl directs us to her face or the white muslin frames her hair, billowing off to the right so as to counterbalance the thrust of her left arm. Note too, the relationship between her corkscrew curls and the tendril decorations on the wooden base of the divan. Everything, it would appear, seems designed to harmonize the figure within the setting.

Contemporary critics, reflecting the taste of the time, thought that Ingres had taken things too far, describing the sitter as “so enveloped in draperies that one spends a long time in guesswork before recognizing anything.” In Ingres’ defense, though, despite the richness of surface the figure still dominates the canvas. This is achieved, among other things, by that central vertical axis, running down from her right eye to the ring on her right hand. The imagined line is bisected by a pool of light – the brightest passage of the painting and one that also marks its central axis—reflected off the ribbon sash on her Empire Line dress. These subtle interplays of color and line create harmonious forms which some critics have likened to music.

The oval frame

The carefully worked out substructure is a response to the challenges created by the oval shaped frame. In order not to have the figure topple one way or another, the picture’s dimensions need to be accommodated to ensure the parts relate to the whole. Ingres manages this repeatedly in the painting. The supple arabesques formed by her shawl, for example, echo the pictorial space, as of course does the oval of her face. This is also true of the treatment of the body itself; most dramatically, Madame Rivière’s right arm has been deliberately elongated so as to rhyme with the curve of the frame.

At home in her imperial finery

In the end, we are left with the impression of an individual who is very much at home in her surroundings. So much so, in fact, as to be almost fortified by them. They compliment and flatter her too. Notice, for example, the way that muslin serves to veil her left shoulder, concealing any awkwardness in the passage between her arm and her torso kindly negating any signs of aging. In her mid-thirties, she looks ageless, a woman in the prime of her life secure in her Imperial finery. We are reminded of those Roman and Etruscan matrons reclining on their sarcophagi, unaffected by the ravishes of time, death and decay.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Napoleon on His Imperial Throne

by DR. BRYAN ZYGMONT

Napoleon, art and politics

Few world leaders have had a better understanding of the ways in which visual art can do political work on their behalf than did Napoleon Bonaparte. From the time he ascended to power during the French Revolution until his ultimate removal from office in 1815, Napoleon utilized art (and artists) to speak to his political (and sometimes his military) might. One of the best-known images that serves this exact end is Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s 1806 painting Napoleon on His Imperial Throne. In this painting, Ingres shows Napoleon not only as a emperor of the French, but almost as if he were a divine ruler.

Shortly after the turn of the nineteenth century, Ingres was one of the rising stars and fresh voices of the French neoclassical movement, an artistic style that was in part founded by Ingres’s prestigious teacher, Jacques-Louis David. By 1806, David had painted Napoleon many times. Two of the most famous of these works are Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801) and The Coronation of Napoleon (1805-1807), the latter, a painting that is contemporary with Ingres’s portrait. In both of these images, David went out of his way to glorify his patron. This too was one of Ingres’s primary goals, and the portraitist utilized furniture, attire, and setting to transform Napoleon from mere mortal to powerful god.

Transforming Napoleon

Throne and armrest

Napoleon sits on an imposing, round-backed and gilded throne, one that is similar to those that God sits upon in Jan van Eyck’s Flemish masterwork, the Ghent Altarpiece (1430-32) (comparison above). Its worth noting that, as a result of the Napoleonic Wars, the central panels of the Ghent Altarpiece that include the image of God upon a throne, were in the Musée Napoléon (now the Louvre) when Ingres painted this portrait. The armrests in Ingres’s portrait are made from pilasters that are topped with carved imperial eagles and highly polished ivory spheres (left).

Rug

A similarly spread-winged imperial eagle appears on the rug in the foreground. Two cartouches can be seen on the left-hand side of the rug (below). The uppermost is the scales of justice (some have interpreted this as a symbol for the zodiac sign for Libra), and the second is a representation of Raphael’s Madonna della Seggiola (1513-14), an artist and painting Ingres particularly admired.

Crest

One final ancillary element should be mentioned. On the back wall over Napoleon’s left shoulder is a partially visible heraldic shield. The iconography for this crest, however, is not that of France, but is instead Italy and the Papal States. This visually ties the Emperor of the French to his position—since 1805—as the King of Italy.

Robes and accessories

It is not only the throne that speaks to rulership. He unblinkingly faces the viewer. In addition, Napoleon is bedazzled in attire and accouterments of his authority. He wears a gilded laurel wreath on his head, a sign of rule (and more broadly, victory) since classical times.

In his left hand Napoleon supports a rod topped with the hand of justice, while with his right hand he grasps the scepter of Charlemagne. Indeed, Charlemagne was one of the rulers Napoleon most sought to emulate (one may recall that Charlemagne’s name was incised on a rock in David’s earlier Napoleon Crossing the Alps). An extravagant medal from the Légion d’honneur (like the one below, right) hangs from the Emperor’s shoulders by an intricate gold and jewel-encrusted chain.

Although not immediately visible, a jewel-encrusted coronation sword hangs from his left hip (image below). The reason why the sword—one of the most recognizable symbols of rulership—can hardly be seen is because of the extravagant nature of Napoleon’s coronation robes. An immense ermine collar is under Napoleon’s Légion d’honneur medal. Ermine—a kind of short-tailed weasel—have been used for ceremonial attire for centuries and are notable for their white winter coats that are accented with a black tip on their tail. Thus, each black tip on Napoleon’s garments represents a separate animal. Clearly, then, Napoleon’s ermine collar—and the ermine lining under his gold-embroidered purple velvet robes—has been made with dozens of pelts, a certain sign of opulence. The purple color of the garment was a deliberate choice, and has a long tradition as a hue restricted for imperial use. Indeed, Roman emperors had exclusive right to wear purple, and it was through this tradition that Jesus also came to wear violet robes. All these elements—throne, scepters, sword, wreath, ermine, purple, and velvet—speak to Napoleon’s position as Emperor.

Position

But it is not only what Napoleon wears. It is also how the emperor sits. In painting this portrait, Ingres borrowed from other well-known images of powerful male figures. Perhaps the most notable was a long-since-destroyed but still well known image of Zeus (the ancient Greek God, king of the gods of Mount Olympus) that Phidias, one of the most famous of Greek sculptors, made around 435 B.C.E. This ‘type’ showed Zeus seated, frontal, and with one arm raised while the other was more at rest. Indeed, this is the posture Jupiter takes in a slightly later Ingres painting, Jupiter and Thetis (1811). Thus, Ingres is working in yet another rich visual tradition, and in doing so, seems to remove Napoleon Bonaparte from the ranks of the mortals of the earth and transforms him into a Greek or Roman god of Mt. Olympus. Never once accused of modesty, there is no doubt that Napoleon approved of such a comparison.

Looking at Ingres’s Napoleon on His Imperial Throne is a visually overwhelming experience. Its colossal size (it measures 8’6” x 5’4”) and neoclassical precision eloquently speak to Napoleon’s political authority and military power. The low eye level—about that of Napoleon’s knees—also indicates that the viewer is looking up at the seated ruler, as if kneeling before him. The sum total of this painting is not just the coronation of Napoleon, but almost his divine apotheosis. Ingres shows him not just as a ruler, but as omnipotent immortal.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Musée de l’Armée, Paris

Ingres, Napoleon on His Imperial Throne from learner.org

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Apotheosis of Homer

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

A student of the past

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (pronounced: aah-n Gr-ah) was Jacque-Louis David’s most famous student. And while this prolific and successful artist was indebted to his teacher, Ingres quickly turned away from him. For his inspiration, Ingres, like David in his youth, rejected the accepted formulas of his day and sought instead to learn directly from the ancient Greek as well as the Italian Renaissance interpretation of this antique ideal.

Ingres exhibited Apotheosis of Homer (1827) in the annual Salon. His grandest expression of the classical ideal, this nearly seventeen foot long canvas reworks Raphael’s Vatican fresco, The School of Athens (1509-1511) and thus pays tribute to the genius Ingres most admired.

As Raphael had done three hundred years earlier, Ingres brought together a pantheon of luminaries. Like secular sacra-conversaziones, the Raphael and the Ingres bring together figures that lived in different eras and places.

But while Raphael celebrated the Roman Church’s High Renaissance embrace of Greek intellectuals (philosophers, scientists, etc.), Ingres also includes artists (visual and literary).

Homage to artists

Set on a pedestal at the center of the Apotheosis of Homer, the archaic Greek poet is conceived of as the wellspring from which the later Western artistic tradition flows. The entire composition functions somewhat like a family tree. Homer is framed by both historical and allegorical figures and an Ionic temple that enforces the classical ideals of rational measure and balance. Nike, the winged Greek goddess of the running shoe (ahem, of victory) crowns Homer with a wreath of laurel, while below him sit personifications of his two epic poems, The Odyssey (in green and holding an oar) and The Illiad (in red and seated beside her sword).

Note the following figures (please consider their implied importance according to their placement relative to Homer):

- Dante, the Medieval poet and humanist stands at the extreme left wearing a red scull cap and cape;

- Phidias, the greatest of ancient sculptors is standing to the right of Homer, in red, holding a mallet;

- Raphael, third from the left edge, top row, is in profile and wears Renaissance garb; Ingres (he’s put himself in rather good company don’t you think?) is the young face looking out at us beside Raphael;

- Poussin, points us toward Homer from the lower left of the canvas; and

- Michelangelo is the bearded figure at lower right.

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Between Neoclassicism and Romanticism: Ingres, La Grande Odalisque

by DR. BRYAN ZYGMONT

A quick study

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres was an artist of immense importance during the first half of the nineteenth century. His father, Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres was a decorative artist of only minor influence who instructed his young son in the basics of drawing by allowing him to copy the family’s extensive print collection that included reproductions from artists such as Boucher, Correggio, Raphael, and Rubens. In 1791, at just 11 years of age, Ingres the Younger began his formal artistic education at the Académie Royale de Peinture, Sculpture et Architecture in Toulouse, just 35 miles from his hometown of Montauban.

Ingres was a quick study. In 1797—at the tender age of 16 years—he won the Académie’s first prize in drawing. Clearly destined for great things, Ingres packed his trunks less than six months later and moved to Paris to begin his instruction in the studio of Jacques-Louis David, the most strident representative of the Neoclassical style. David stressed to those he instructed the importance of drawing and studying from the nude model. In the years that followed, Ingres not only benefitted from David’s instruction—and the prestige and caché that such an honor bestowed—but also learned from many of David’s past students who frequented their former teacher’s studio. These artists comprise a “who’s who” of late-eighteenth-century French neoclassical art and include painters such as Jean-Germain Droais, Anne-Louis Girodet, and Antoine Jean-Gros.

The Rome Prize—a bright future

The Prix de Rome—the Rome Prize—was the most prestigious fellowship that the French government awarded to a student at the Paris École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts), the leading art school in France from its founding in 1663 until it was finally dissolved in 1968. The recipient of the Prix de Rome was provided with a living stipend, studio space at the French Academy in Rome, and the opportunity to immerse themselves in Rome’s classical ruins and the works of Renaissance and Baroque masters. It promised to be a great five years for any aspiring artist. Joseph-Marie Vien, David’s own teacher, had won the award in 1743. David won the award in 1774—after four unsuccessful attempts. Ingres was formally admitted to the painting department of the École des Beaux-Arts in October 1799. The following year—in only his first attempt—Ingres tied for second place. In 1801, his painting of The Ambassadors of Agamemnon in the Tent of Achilles won him the Prix de Rome. He turned 21 years old that August. Ingres had a bright future indeed.

Hierarchy of subjects

The Prix de Rome—to say nothing of the instruction Ingres received within David’s studio and at the École des Beaux-Arts—reinforced the hierarchy of the subjects of painting that had been a foundational element of French art instruction for more than a century. Artists with the greatest skill aspired to complete grand manner history paintings. These were immense compositions often depicting narratives from the classical past or from the Jewish and Christian Bibles. In addition to being large—and expensive—these works allowed the most accomplished and intellectually engaged artists to provide the art-viewing public with an important moral message—an exemplum virtutis (an example of virtue). David’s 1784 masterwork Oath of the Horatii is one such example.

The nude (and not the classical past)

Due to the financial woes of the French government in the first years of the nineteenth century, Ingres’s Prix de Rome—which he won in 1801—was delayed until 1806. Two years later, Ingres sent to the École three compositions—intended to demonstrate his artistic growth while studying at the French Academy in Rome. Interestingly, all three of these works—The Valpinçon Bather, the so-called Sleeper of Naples, and Oedipus and the Sphinx—depict elements of the female nude (to be fair, however, the sphinx is not human). The first two, however, do not depict a story from the classical past. Instead, nearly the entire focus of each composition is on the female form. While Ingres has retained the formal elements that were so much a part of his neoclassical training—extreme linearity and a cool, “licked’ surface” (where brushwork is nearly invisible)—he had begun to reject neoclassical subject matter and the idea that art should be morally instructive. Indeed, by 1808, Ingres was beginning to walk on both sides of the neoclassical/romantic divide. In few works is a Neoclassical style fused with a romantic subject matter more clearly than in Ingres’s 1814 painting La Grande Odalisque.

Ingres completed his time at the French Academy in Rome in 1810. Rather than immediately return to Paris however, he remained in the Eternal City and completed several large-scale history paintings. In 1814 he traveled to Naples and was employed by Caroline Murat, the Queen of Naples (who also happened to be Napoleon Bonaparte’s sister). She commissioned La Grande Odalisque, a composition that was intended to be a pendant to his earlier composition, Sleeper of Naples.

At first glance, Ingres’s subject matter is of the most traditional sort. Certainly, the reclining female nude had been a common subject matter for centuries. Ingres was working within a visual tradition that included artists such as Giorgione (Sleeping Venus, 1510), Titian (Venus of Urbino, 1538) and Velazquez (Rokeby Venus, 1647-51). But the titles for all three of those paintings have one word in common: Venus. Indeed, it was common to cloak paintings of the female nude in the disguise of classical mythology.

Ingres (and Goya, who was working within a similar vein with his La Maja Desnuda—see below) refused to disguise who and what his female figure was. She was not the Roman goddess of love and beauty. Instead, she was an odalisque, a concubine who lived in a harem and existed for the sexual pleasure of the sultan.

In his painting La Grande Odalisque (below), Ingres transports the viewer to the Orient, a far-away land for a Parisian audience in the second decade of the nineteenth century (in this context, “Orient” means Near East more so than the Far East). The woman—who wears nothing other than jewelry and a turban—lies on a divan, her back to the viewer. She seemingly peeks over her shoulder, as if to look at someone who has just entered her room, a space that is luxuriously appointed with fine damask and satin fabrics. She wears what appears to be a ruby and pearl encrusted broach in her hair and a gold bracelet on her right wrist. In her right hand she holds a peacock fan, another symbol of affluence, and another piece of metalwork—a facedown bejeweled mirror, perhaps?—can be seen along the lower left edge of the painting.

Along the right side of the composition we see a hookah, a kind of pipe that was used for smoking tobacco, hashish and opium. All of these Oriental elements—fabric, turban, fan, hookah—did the same thing for Ingres’s odalisque as Titian’s Venetian courtesan being labeled “Venus”—that is, it provided a distance that allowed the (male) viewer to safely gaze at the female nude who primarily existed for his enjoyment.

And what a nude it is. When glancing at the painting, one can immediately see the linearity that was so important to David in particular, and the French neoclassical style more broadly. But when looking at the odalisque’s body, the same viewer can also immediately notice how far Ingres has strayed from David’s particular style of rendering the human form—look for instance at her elongated back and right arm. David was largely interest in idealizing the human body, rendering it not as it existed, but as he wished it did, in an anatomically perfect state. David’s commitment to the idealizing the human form can clearly be seen in his preparatory drawings for his never completed Oath of the Tennis Court(left). There can be no doubt that this is how David taught Ingres to render the body.

Students often stray from their teacher’s instruction, however. In La Grande Odalisque, Ingres rendered the female body in an exaggerated, almost unbelievable way. Much like the Mannerists centuries earlier—Parmigianino’s Madonna of the Long Neck (c. 1535) immediately comes to mind—Ingres distorted the female form in order to make her body more sinuous and elegant. Her back seems to have two or three more vertebrae than are necessary, and it is anatomically unlikely that her lower left leg could meet with the knee in the middle of the painting, or that her left thigh attached to this knee could reach her hip. Clearly, this is not the female body as it really exists. It is the female body, perhaps, as Ingres wished it to be, at least for the composition of this painting. And in this regard, David and his student Ingres have attempted to achieve the same end—idealization of the human form—though each strove to do so in markedly different ways.

A brief comparison between teacher and student makes clear how far Ingres had strayed from the neoclassical path David had laid. In some ways, La Grande Odalisque is based upon David’s 1800 portrait of Madame Récamier.

Both images show a recumbent woman who peers over her shoulder to look at the viewer. David and Ingres utilize line in a similar way. However, David depicts Récamier at the height of neoclassical fashion, wearing an Empire waistline dress and an à la grecque hairstyle. One gets the sense that there is real a body underneath that dress. In contrast, Ingres’s odalisque is a naked “other” from the Orient, and no clothing could disguise the elongations and anatomical inaccuracies of her body. David remained a committed neoclassicist, while his former student retained his neoclassical line to embrace, in this case, a geographically distant and romantic subject. This tension between Neoclassicism and Romanticism will continue throughout the first half of the nineteenth century as painters will tend to side with either Ingres and his precise linearity or the painterly style of the younger painter Eugène Delacroix.

Additional resources:

The French Academy in Rome on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

The Prix de Rome

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Painting colonial culture: Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, La Grande Odalisque, 1814, Oil on canvas, 36″ x 63″ (91 x 162 cm), (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Early Romantic tendencies

It would be easy to characterize Ingres as a consistent defender of the Neoclassical style from his time in Jacques Louis David’s studio into the middle of the 19th century. But the truth is more interesting than that.

Ingres actually returned to Neoclassicism after having first rejected the lessons of his teacher David. He could even be said to have laid the foundation for the emotive expressiveness of Romanticism (the new style of Gericault and the young Delacroix that Ingres would later hold the line against). Ingres’s early Romantic tendencies can be seen most famously in his painting La Grande Odalisque of 1814.

La Grande Odalisque

Here a languid nude is set in a sumptuous interior. At first glance this nude seems to follow in the tradition of the Great Venetian masters, see for instance, Titian’s Venus of Urbino of 1538 (left). But upon closer examination, it becomes clear that this is no classical setting. Instead, Ingres has created a cool aloof eroticism accentuated by its exotic context. The peacock fan, the turban, the enormous pearls, the hookah (a pipe for hashish or perhaps opium), and of course, the title of the painting, all refer us to the French conception of the Orient. Careful—the word “Orient” does not refer here to the Far East so much as the Near East or even North Africa.

In the mind of an early 19th century French male viewer, the sort of person for whom this image was made, the odalisque would have conjured up not just a harem slave—itself a misconception—but a set of fears and desires linked to the long history of aggression between Christian Europe and Islamic Asia (see the essay on Orientalism). Indeed, Ingres’ porcelain sexuality is made acceptable even to an increasingly prudish French culture because of the subject’s geographic distance. Where, for instance, the Renaissance painter Titian had veiled his eroticism in myth (Venus), Ingres covered his object of desire in a misty, distant exoticism.

Some art historians have suggested that colonial politics also played a role. France was at this time expanding its African and Near Eastern possessions, often brutally. Might the myth of the barbarian have served the French who could then claim a moral imperative? By the way, has anyone noticed anything “wrong” with the figure’s anatomy?

Additional resources:

Extra vertebrae in Ingres’ La Grande Odalisque, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Orientalism at the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Théodore Géricault

Théodore Géricault, Raft of the Medusa

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Théodore Géricault, Raft of the Medusa, 1818-19, oil on canvas, 4.91 x 7.16m (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Théodore Géricault, Portraits of the Insane

by BEN POLLITT

After The Raft of the Medusa

At the end of 1821 the leading Romantic painter in France, Théodore Géricault, returned from a year-long stay in England where crowds had flocked to see his masterpiece The Raft of the Medusa displayed in the Egyptian Hall in Pall Mall, London. Despite the success of the exhibition, the French government still refused to buy the painting and his own prodigious spending meant that he was strapped for cash and in no position to embark on another ambitious and expensive large scale project like The Raft. His health too was soon to suffer. On his return to France, a riding accident led to complications, causing a tumor to develop on the spine that proved fatal. He died, aged 32, in January 1824.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of his last years were his portraits of the insane. There were ten of them originally. Only five have survived: A Woman Addicted to Gambling, A Child Snatcher, A Woman Suffering from Obsessive Envy, A Kleptomaniac; and A Man Suffering from Delusions of Military Command.

No information is available for those that have been lost. According to the artist’s first biographer, Charles Clément, Géricault painted them after returning from England for Étienne-Jean Georget (1795-1828), the chief physician of the Salpêtrière, the women’s asylum in Paris. The paintings were certainly in Georget’s possession when he died.

Three theories for the commission

How the two men met is not known for sure. Possibly Georget treated Géricault as a patient, or perhaps they met in the Beaujon Hospital, from whose morgue Géricault had taken home dissected limbs to serve as studies for his figures in The Raft. What is more debated though, is Georget’s role in the production of the paintings. There are three main theories. The first two link the portraits to the psychological toll taken out of Géricault whilst producing his great masterpiece and the nervous breakdown he is believed to have suffered in the autumn following its completion in 1819. The first theory runs that Georget helped him to recover from this episode and that the portraits were produced for and given to the doctor as a gesture of thanks; the second puts forward that Georget, as the artist’s physician, encouraged Géricault to paint them as an early form of art therapy; and the third is that Géricault painted them for Georget after his return from England to assist his studies in mental illness.

It is this last that is generally held to be the most likely. Stylistically, they belong to the period after his stay in England, two years after his breakdown. Also, the unified nature of the series, in terms of their scale, composition and color scheme suggest a clearly defined commission, while the medical concept of “monomania” shapes the whole design.

Early modern psychiatry

A key figure in early modern psychiatry in France was Jean-Etienne-Dominique Esquirol (1772-1840), whose main area of interest was “monomania,” a term no longer in clinical use, which described a particular fixation leading sufferers to exhibit delusional behavior, imagining themselves to be a king, for example. Esquirol, who shared a house with his friend and protégé Georget, was a great believer in the now largely discredited science of physiognomy, holding that physical appearances could be used to diagnose mental disorders. With this in mind, he had over 200 drawings made of his patients, a group of which, executed by Georges-Francoise Gabriel, were exhibited at the Salon of 1814. As an exhibitor himself that year, it seems highly likely that Géricault would have seen them there.

Georget’s work developed on Esquirol’s. An Enlightenment figure, Esquirol rejected moral or theological explanations for mental illness, seeing insanity, neither as the workings of the devil nor as the outcome of moral decrepitude, but as an organic affliction, one that, like any other disease, can be identified by observable physical symptoms. In his book On Madness, published in 1820, following Esquirol, Georget turns to physiognomy to support this theory:

In general the idiot’s face is stupid, without meaning; the face of the manic patient is as agitated as his spirit, often distorted and cramped; the moron’s facial characteristics are dejected and without expression; the facial characteristics of the melancholic are pinched, marked by pain or extreme agitation; the monomaniacal king has a proud, inflated expression; the religious fanatic is mild, he exhorts by casting his eyes at the heavens or fixing them on the earth; the anxious patient pleads, glancing sideways, etc.

The clumsy language here—“the idiot’s face is stupid”—seems a world away from Géricault’s extraordinarily sensitive paintings, a point that begs the question whether Géricault was doing more than simply following the good doctor’s orders in producing the series, but instead making his own independent inquiries.

Géricault had many reasons to be interested in psychiatry, starting with his own family: his grandfather and one of his uncles had died insane. His experiences while painting The Raft must also have left their mark. The Medusa’s surgeon, J.B. Henry Savigny, at the time Géricault interviewed him, was writing an account of the psychological impact the experience had had on his fellow passengers and, of course, there was Géricault’s own mental breakdown in 1819. It seems only natural then that he would be drawn to this new and exciting area of scientific study.

Alternatively, some critics argue that Géricault’s work is a propaganda exercise for Georget, designed to demonstrate the importance of psychiatrists in detecting signs of mental illness. In their very subtleties they show just how difficult this can be, requiring a trained eye such as Georget’s to come to the correct diagnosis. According to Albert Boime, the paintings were also used to demonstrate the curative effects of psychiatric treatment. If the five missing paintings were ever found, he argues, they would depict the same characters—but after treatment—showing their improved state, much like ‘before and after’ photographs in modern day advertising.

This, of course, is impossible to prove or disprove. What is more challenging is Boime’s general criticisms of early psychiatry which, he argues, by classifying, containing and observing people was effective only in silencing the voices of the mentally ill, rendering them invisible and therefore subject to abuse. The fact that the sitters of the paintings are given no names, but are defined only by their illnesses would seem to confirm this view and, for that reason, many modern viewers of the paintings do feel disconcerted when looking at them.

The portraits

The five surviving portraits are bust length and in front view, without hands. The canvases vary in dimensions but the heads are all close to life-size. The viewpoint is at eye level for the three men but from above for the women, indicating that the paintings were executed in different places. It seems likely that the women were painted in the women’s hospital Salpêtrière, while the men were selected from among the inmates of Charenton and Bicȇtre. None of the sitters is named; they are identified by their malady. None look directly at the viewer, contributing to an uneasy sense of distractedness in their gazes that can be read as stillness, as though they are lost in their own thoughts, or as disconnectedness from the process in which they are involved. These are not patrons and have had no say in how they are depicted.

Each is shown in three-quarter profile, some to the left, some to the right. The pose is typical of formal, honorific portraits, effecting a restrained composition that does not make it apparent that they are confined in asylums. There is no evidence of the setting in the backgrounds either, which are cast in shadow, as are most of their bodies, drawing the focus largely on their faces.

The dark coloring creates a sombre atmosphere, evocative of brooding introspection. Their clothing lends them a degree of personal dignity, giving no indication as to the nature of their conditions, the one exception being the man suffering from delusions of military grandeur who wears a medallion on his chest, a tasseled hat and a cloak over one shoulder, which point to his delusions. The medallion has no shine to it and the string that it hangs from looks makeshift and worn.

The paintings were executed with great speed, entirely from life and probably in one sitting. Critics often remark on the painterly quality of the work, the extraordinary fluency of brushwork, in contrast with Géricault’s early more sculptural style, suggesting that the erratic brushwork is used to mirror the disordered thoughts of the patients. In places it is applied in almost translucent layers, while in others it is thicker creating highly expressive contrasts in textures.

Romantic scientists

What perhaps strikes one most about the portraits is the extraordinary empathy we are made to feel for these poor souls, who might not strike us immediately as insane, but who certainly exhibit outward signs of inward suffering.

In bringing the sensitivity of a great artist to assist scientific inquiry, Géricault was not alone among Romantic painters. John Constable’s cloud studies, for example, were exactly contemporary with the portraits and provide an interesting parallel.

Both artists capture brilliantly the fleeting moment, the shifting movements in Constable’s cumulus, stratus, cirrus and nimbus, in Géricault the complex play of emotions on the faces of the insane.

Not since the Renaissance has art illustrated so beautifully the concerns of the scientific domain; in Géricault’s case teaching those early psychiatrists, we might be tempted to think, to look on their patients with a more human gaze.

Additional resources:

The Woman with Gambling Mania at the Louvre

Portrait of a Kleptomaniac at the Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent

“Portraying Monomaniacs to Service the Alienist’s Monomania: Géricault and Georget” by Albert Boime

Man with the ‘Monomania’ of Child Kidnapping, Théodore Géricault in The Guardian

Eugène Delacroix

Eugène Delacroix, an introduction

Born in 1798, the French Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix began life as child of privilege and grew up during the age of Napoleon. The funny thing is, he didn’t like being called a Romantic artist. Instead, Delacroix saw himself as a painter who carried on the tradition of French painting at its best, not as someone who wanted to overturn it. “Glory is not a vain word for me,” [1] he once wrote, and Delacroix imagined his name spoken in the same breath with the other “great” French painters such as Charles Lebrun and Jacques-Louis David. For nineteenth-century viewers, Delacroix seemed fearless in his ability to create dramatic images painted with an intensity of color and expression that no one else could match.

A young man in Paris

As a young man, Delacroix was at the heart of creative life in Paris and later became a hero of progressive artists and writers such as Baudelaire, Manet, and Monet, but he retained all of the elegance and ambition of his family’s aristocratic background. His father, Charles, found great success as a landowner and government official before his death in 1803. Delacroix’s brothers and other relatives served as soldiers and ambassadors in the Napoleonic government. Delacroix’s mother Victoire died in 1814, when Eugène was just sixteen. Although his father had left a fortune to his family, it had been poorly managed, and by 1822 there was nothing left. Delacroix would have to make his way in the world with just his talent and a few family connections.

Delacroix’s art owed much to his education and the company he kept as a young man in Paris. He attended the Lycée Louis-le-Grand, a prestigious school that is still associated with the French elite. There, and later in the company of his friends, he came to love Greek drama, Shakespeare, and modern literature. When he was seventeen, Delacroix entered the studio of the conservative painter Pierre-Narcisse Guérin and, as importantly, he began to study in the Louvre, copying the paintings of Veronese, Titian, and Rubens with other young painters.

In Guérin’s studio, Delacroix met the painter Théodore Géricault, who would have an important influence on Delacroix’s first major canvas (The Barque of Dante). Géricault’s dramatic brushwork and daring compositions made a deep impression on young Delacroix. In 1818, Géricault began to work independently on The Raft of the Medusa, in a studio rented specifically for that purpose. There Delacroix watched Géricault work quickly and expressively on the massive canvas. We know that Delacroix served as a model for one of the figures in the foreground, and he vividly recalled feeling completely overwhelmed with admiration and emotion when he saw the near-finished painting.

A dramatic debut

Delacroix’s first painting presented in the annual Paris Salon exhibition, The Barque of Dante (1822), reflected Géricault’s dramatic approach and all of Delacroix’s studies in the Louvre. Drawn from the Italian Renaissance poet Dante’s Divine Comedy, the painting depicts Dante guided into Hell by the Roman poet Virgil as stormy seas and demonic figures attack their boat. The figures and drama, recalling Michelangelo and Rubens, marked the artist as part of the new modern style that would soon be called Romantic.

The big three

After his debut painting, Delacroix followed up with three of his best-known works, all drawn from contemporary events and literature. These paintings marked Delacroix as the leader of the modern, Romantic movement. In the public imagination, the term Romantic pitted Delacroix against the more conservative painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who embodied a conservative, classic approach to painting based on the primacy of line, while Delacroix represented a more expressive, modern painterly style focused on color. While Delacroix never liked being labeled a Romantic, he valued all the recognition that came from presenting sensational Salon paintings.

Massacre at Chios depicts the Greeks of the island of Chios after a defeat by the Ottoman Turks during the Greek Wars of Independence. The French saw themselves reflected in the Greek struggle for freedom, and the Turkish cavalryman on the right added drama and foreign glamour. There was always a crowd in front of the painting at the Salon exhibition. Delacroix offered the viewers a bit of tradition and, also, painterly innovation. The frieze-like composition of figures across the canvas recalled the Neoclassical paintings of Jacques-Louis David, and conservative critics liked the reclining, bearded male figure. Those with a taste for a more progressive, Romantic style responded to the fluidity of the painting and intense color contrasts that seemed drawn from Rubens and expressed the passionate nature of the artist.

Next came the epic Death of Sardanapalus (1827), a massive canvas depicting the last Assyrian king watching his concubines and horses being slaughtered as he burns his palace down around him. The subject is taken from a play by the Romantic English poet Byron, and the painting is a swirling, violent scene dominated by a red that permeates the canvas. Audiences were shocked and dazzled. The painting reflected contemporaneous French ideas of the people of the East as hedonistic, violent and fatalistic. This worldview, associated with the term Orientalism in art history, was part of an overall colonialist attitude that defined Western Europe as a model of reason and moderation in contrast to the excesses associated with the so-called Orient. As such, the audience could revel in the violence, eroticism and glamour because it depicted a world defined as completely different and removed from modern Paris. But, for most viewers, Delacroix had gone too far. The painting broke too many rules. Even his supporters discerned no underlying structure to the painting’s composition and saw only an indulgent use of color.

One of the most famous paintings in France completes the trio: Liberty Leading the People (1830). It commemorates the Revolution of 1830 that deposed Charles X (brother of Louis XVI) and brought an end to the Bourbon Restoration that had followed Napoleon. The events of 1830, unlike the conflict in Greece or the violent fantasy of Sardanapalus, unfolded on Delacroix’s doorstep. Rather than taking part in the conflict, he stayed off the streets and out of danger. Only after order was restored did he take a stand. He wrote, “I have undertaken a modern subject, a barricade, and although I may not have fought for my country, at least I shall have painted for her.”[2] While many saw a call to revolution in Liberty Leading the People, Delacroix saw a classic history painting with an allegorical figure, bare-breasted Liberty, carrying the tricolor flag of the French republic over the barricade.

For the official world of French painting, Liberty Leading the People posed a problem. In a country so rocked by revolutions and violence in the previous decades, was it prudent to have a painting celebrating rebellion on public view? This question dogged the French state for decades. After its first exhibition in the Paris Salon, Delacroix was awarded the cross of the Legion of Honor, and the painting was purchased by the state and put on view in Paris’ gallery of contemporary art in the Luxembourg Palace. But by 1832 the monarchy removed the painting, and it was not exhibited again until 1848. It was removed again in 1850 and not put on permanent display until 1862. Today, it is an iconic image of the ideals of the French republic.

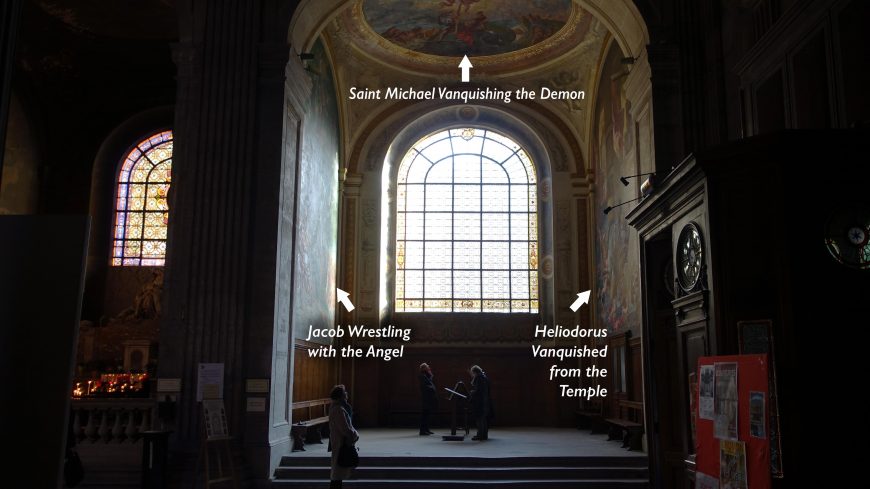

In the years after Liberty Leading the People, Delacroix shifted his focus from large-scale canvases for the Salon to new subjects. Through his association with members of the government, he was invited to North Africa as part of a diplomatic mission and produced work from that voyage. Later he received commissions to create wall and ceiling paintings for important government buildings and churches in Paris. This was not his only work, but these projects shaped his professional life. During these years, his friends were well-known bohemian artists, writers and composers, such as the novelist George Sand and her lover, the composer Frédéric Chopin. With the Romantic sculptor Antoine Barye, he visited the Paris zoo to draw and paint the exotic tigers and other animals. He also worked as a printmaker, producing etchings and lithographs that included images of animals, depictions of North Africa and illustrations from literature.

A voyage to Morocco

In January 1832, Delacroix, who had not traveled outside of France before, took part in a diplomatic mission to Morocco. Before the trip, he had only known the world of North Africa and the Middle East from literature and images. After his arrival in Tangier, he wrote a friend, “I have just walked through the city. I am dizzy with what I have seen.”[3] One of the earliest French painters to depict the people and cultures of North Africa, Delacroix filled his notebooks with ink sketches and watercolors.

When he returned to Paris, Delacroix began to exhibit work drawn from his voyage, beginning with A Street in Meknes (1832). Most significant was The Women of Algiers (1834) exhibited to great acclaim in the Paris Salon. According to contemporary writer Philippe Burty, Delacroix had received special permission to enter an Algerian harem — part of a home off-limits to men — and sketched two women he encountered there. He used the visit and his sketches as the basis for the two principal figures in The Women of Algiers. While this account is in doubt today (after all, he created the painting in Paris using models in the studio), the Salon audience was entranced, embracing the quiet intimacy of the scene, its exotic aura, and beautiful intense colors. Delacroix returned to the subject fifteen years later with The Women of Algiers in Their Apartment (1847-1849) and other artists, such as Pablo Picasso, closely studied and rendered their own versions of the painting.

Paintings for all of Paris

Delacroix also found success creating decorations for important public buildings and churches in Paris. In 1833, he began work on government commissions with paintings for important rooms in the Assemblée Nationale, and followed up with decorations for the library of the Senate (1840–1851). Between 1851 and 1854, he also painted the Salon de la Paix in the Paris City Hall, although his work was unfortunately lost in the fire of 1871. Visitors to the Louvre can see some of Delacroix’s decorative paintings in the Galerie d’Apollon, including Apollo Slays Python, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Before beginning the painting, Delacroix had visited Belgium and his journals record admiration for the freedom, drama, and sublime nature of Rubens’ work that found its way into the swirling colors, dramatic composition, and ethereal light of Apollo Slays Python.

The monumental paintings created after 1830, during the July Monarchy, were followed by a commission to decorate the Chapelle des Anges in the Church of St. Sulpice. He received the commission in 1849, but other work delayed the start on the paintings until 1854. In the Chapelle he depicted three stories that revolved around the biblical Archangel Michael and stories from the Old Testament. This would be his last major project.

The end of an era

As he completed major Salon paintings and public commissions, Delacroix also continued to create smaller easel paintings. Throughout his career he drew, printed, and painted dramatic subjects drawn from history and literature, tales from mythology and Christian subjects that reflected compassion and empathy, as well as animal and still-life images. At his funeral in 1863, people said that his death marked the end of an era in French art and the definitive passing of the “Generation of 1830.” Yet even as Delacroix passed into history, a new generation of rebellious painters led by Édouard Manet had begun to follow in his footsteps by creating art that engaged with the past while pushing toward an entirely new approach to painting.

Notes:

- Eugène Delacroix, Journal, April 29, 1824.

- Barthélémy Jobert, Delacroix (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1997), 130.

- Ibid., 83.

Eugène Delacroix, Scene of the Massacre at Chios

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Eugène Delacroix, Scene of the Massacre at Chios; Greek Families Awaiting Death or Slavery, 1824, oil on canvas, 164″ × 139″ / 419 cm × 354 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Eugène Delacroix, The Death of Sardanapalus

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Eugène Delacroix, The Death of Sardanapalus, 1827, oil on canvas, 12′ 10″ x 16′ 3″ / 3.92 x 4.96 m (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People

by DR. BRYAN ZYGMONT

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People (July 28, 1830), September – December 1830, oil on canvas, 260 x 325 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Poussinists vs. Rubenists

If Jacques-Louis David is the most perfect example of French Neoclassicism, and his most accomplished pupil Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, represents a transitional figure between Neoclassicism and Romanticism, then Eugène Delacroix stands (with, perhaps, Theodore Gericault) as the most representative painter of French romanticism.

French artists in early nineteenth century could be broadly placed into one of two different camps. The Neoclassically trained Ingres led the first group, a collection of artists called the Poussinists (named after the French baroque painter Nicolas Poussin). These artists relied on drawing and line for their compositions. The second group, the Rubenists (named in honor of the Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens), instead elevated color over line. By the time Delacroix was in his mid-20s—that is, by 1823—he was one of the leaders of the ascending French romantic movement.

From an early age, Delacroix had received an exceptional education. He attended the Lycée Imperial in Paris, an institution noted for instruction in the Classics. While a student there, Delacroix was recognized for excellence in both drawing and Classics. In 1815—at the age of only 17—he began his formal art education in the studio of Pierre Guérin, a former winner of the prestigious Prix de Rome (Rome Prize) whose Parisian studio was considered a particular hotbed for romantic aesthetics. In fact, Theodore Gericault, who would soon become a romantic superstar with his Raft of the Medusa (1818-19), was still in Guérin’s studio when Delacroix arrived in 1815. The young artist’s innate skill and his teacher’s able instruction were an excellent match and prepared Delacroix for his formal admission to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts (the School of Fine Arts) in 1816.

Massacre at Chios: Ripped from the headlines

Less than a decade later, Delacroix’s career was clearly on the rise. In 1824, for example, Delacroix exhibited his monumental Massacres at Chios at the annual French Salon. This painting serves as an excellent example of what what Delacroix hoped romanticism could become. Rather than look to the examples of the classical past for a narrative, Delacroix instead looked to contemporary world events for his subject. This “ripped from the headlines” approach was common for many romantic painters.