7.5: Italy in the 15th century- Early Renaissance (II)

- Page ID

- 67071

Sculpture and architecture

Donatello, St. Mark

by DR. DAVID BOFFA

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Donatello, St. Mark, 1411-13, marble, 93″ (236 cm) (Orsanmichele, Florence). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

A humorous anecdote

The sixteenth-century artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari gives us a humorous anecdote about Donatello’s Saint Mark. Supposedly, when the patrons first saw the statue standing on the ground they were displeased with it, but Donatello convinced them to let him install it in its niche, where he would finish working on it. The patrons agreed, the statue was installed, and Donatello covered it up for fourteen days—pretending to work on it but in reality not touching it. When it was finally uncovered, everyone viewed the statue with wonder. The only difference was the installation of the work in its proper context. The artist had included distortions to account for the sculpture being seen from below (in its original location its base would be just above the height of an average person—see image at the bottom of this page). Some of these distortions include a torso and neck that are slightly longer than expected, which would be visually corrected when viewed from below (and the neck is hidden by a flowing beard).

Although Vasari’s story is apocryphal, the visual evidence does suggest that Donatello—in this work and others—was keenly interested in viewer perception. This sensitivity to audience and the ability to manipulate his viewers through his works in stone and bronze are part of what makes him such a distinctive figure—and part of why his Saint Mark still has the ability to astound us with its power and expressiveness.

This over-life-size marble, carved from a single, shallow block of stone, portrays the evangelist Saint Mark standing on a pillow, holding a book in his left hand, staring intently into the distance. Rendering a convincingly soft pillow in marble is a testament to the sculptor’s mastery of the material (and perhaps a reference to the patrons, which we’ll get to later).

Apart from this gaze, his face is defined by a long, intricately carved beard whose wavy curves reach down to the base of his neck. The rich folds of the toga he wears convey the expressiveness of fabric—bunching up at his waist, for instance, and falling dramatically around his legs—while also responding to and suggesting the body underneath. Note, for example, how his left knee—slightly forward—pulls at the garment, and how even when the fabric is piled up, as it is on his hip, it manages to convey the body’s physicality. Consider the extraordinary skill in turning hard stone into something that looks like soft, malleable fabric.

Contrapposto

Saint Mark’s stance is classic contrapposto—an Italian word loosely translated as “contrasted” or “opposed” and that refers to a naturalistic way of portraying the human form that originated in ancient Greece. Saint Mark supports his weight primarily on his right leg, a point emphasized by the strong vertical lines of the toga over that leg—lines that seem to mimic the fluting on Greek and Roman columns. The saint’s hips are at a slight angle and his left leg, bent at the knee as though about to step forward, is far more relaxed. His upper body is the opposite: the left arm is engaged in holding his book—a reference to his status as one of the authors of the Gospels—while his right arm hangs loosely at his side. The slight curve to the body, and the use of both active and relaxed elements, gives the figure an easy, natural gracefulness that reflects how a human would actually stand, and makes it appear as though the saint is caught in the act of stepping out of his niche.

All of these formal elements—the scale, the expressive carving, the interest in the body, the contrapposto—are aspects we have come to associate as new developments in the art of the Early Italian Renaissance.

The commission and setting

Donatello’s commission for Saint Mark was part of a broader campaign to adorn the exterior of Orsanmichele in Florence, Italy. Orsanmichele is and was a building with both civic and religious importance for Florentine citizens. Though constructed in part as a grain warehouse and used as such for decades, Orsanmichele was also a significant site of pilgrimage and religious devotion, due to the presence of a miracle-working image of the Virgin and Child. Plans to decorate the exterior of the building date back to 1339, when the Silk Guild (the Arte della Seta, then known as the Arte di Por Santa Maria) proposed that they and the other major guilds of Florence adorn the external piers of the building with tabernacles (or niches) and life-sized (or bigger) sculptures of saints. The project was slow to get off the ground—only a few works were completed before it came to a stop—but it was revived in the early fifteenth century. At this point, the city government legislated that the guilds had to decorate their tabernacles within ten years or give up their rights to do so.

Orsanmichele was so important to the city that a guild’s ability to commission an artwork for it was considered an honor—if an expensive one. Although the legislation wasn’t strictly enforced, it did inspire a flurry of activity and commissions around Orsanmichele—of which Donatello’s Saint Mark was one example, commissioned by the Linen Weavers’ Guild (the Arte dei Linaiuoli). Other noteworthy sculptures from this period include Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Saint John the Baptist, c. 1414 and Saint Matthew, c. 1420, Nanni di Banco’s Four Crowned Saints, c. 1415, and Donatello’s Saint George, c. 1415.

The Orsanmichele projects provided an opportunity for the guilds to compete with each other, each one commissioning a more luxurious or impressive sculpture. Competition of all sorts—between patrons, artists, even art forms themselves—is a consistent theme of the Renaissance, and in the opening years of the fifteenth century this was on display as guilds vied for public attention and praise via their Orsanmichele commissions. For example, the Cloth Merchants’ Guild (the Arte di Calimala) commissioned Ghiberti’s Saint John the Baptist in bronze rather than marble—a far more costly decision intended to show off the guild’s wealth and outdo its rivals.

Unfortunately, all of the original statues on Orsanmichele—fourteen works—have been placed in either the building’s museum or the Bargello museum. The sculptures in the niches are copies. The result is that we can now view Donatello’s Saint Mark at ground level—exactly as he did not intend it to be viewed!

The artist

Donatello—whose full name was Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi—was born around 1386 in Florence to a middle-class family. He probably trained as a goldsmith as a young man, and eventually spent some time with two of the most important artists of the fifteenth century: Filippo Brunelleschi and Lorenzo Ghiberti. He went with the former to Rome in the opening years of the century, and he spent time in Ghiberti’s workshop from about 1404 to 1407.

By the time of the Saint Mark commission, Donatello had already completed or was at work on several other notable public sculptures, including his marble David (1408-9), Saint John the Baptist (1408-15), and Saint George (c. 1410-15, also for Orsanmichele). These early works—especially Saint John—already exhibit some of the hallmarks of Donatello’s style, including a realism informed by Classical (ancient Greek and Roman) art and a certain psychological intensity. In subsequent decades he would execute original monuments that later generations have come to view as landmarks in Renaissance art: these include the bronze relief of the Feast of Herod for the baptismal font in Siena’s baptistery (c. 1425); the Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata in Padua (c. 1450, the earliest surviving Renaissance equestrian monument); and the Judith and Holofernes (c. 1460), now in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio. These works had an impact not only on his peers but on later sculptors, as well—including on Michelangelo, who can be considered the High Renaissance artistic heir to Donatello. Thanks to a career that spanned over sixty years of activity (Donatello lived until 1466) and that resulted in radical works for major cultural and artistic centers—including Florence, Siena, Padua, and Rome—Donatello became an artist whose fame and impact equaled if not surpassed that of his teachers.

Additional resources:

Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists (1550) on Donatello

Donatello on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Donatello, Saint George

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Donatello, Saint George, c. 1416–17, marble (Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, commissioned by the armorers and sword makers guild for the exterior of Orsanmichele)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Donatello, Feast of Herod

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Donatello, Feast of Herod, panel on the baptismal font of Siena Cathedral, Siena, Italy, Gilded bronze, 1423-27

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Donatello, Madonna of the Clouds

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Donatello, Madonna of the Clouds, c. 1425–35, marble, 33.1 x 32 cm / 13 1/16 x 12 5/8 inches (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Donatello, David

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Donatello, David, bronze, late 1420s to the 1460s, likely the 1440s (Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence)

The following is a conversation about Donatello’s David between Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker:

SZ: Seeing Donatello’s David in the Bargello in Florence makes me realize just how different it is from the later, more famous version of David by Michelangelo. It feels so much more intimate and so much less public.

BH: Well, it is MUCH smaller! After all, this one is only about five feet tall—that’s a few inches shorter than me. And Michelangelo’s David is more than three times this size!

SZ: Because of the small size, and perhaps also because of the warm tones of the bronze, this sculpture seems so immediate and beautiful and vulnerable.

BH: Yes, and of course, Michelangelo’s marble sculpture WAS a public sculpture—it was meant to go in a niche high up in one of the buttresses of the Cathedral of Florence, commissioned by the Office of Works for the Cathedral. We don’t know who commissioned Donatello’s David, but we do know that it was seen in the courtyard of the Medici Palace in Florence, a much more private and intimate setting.

SZ: This intimacy is not simply a result of the nudity, but also of the emotional experience Donatello renders through the face and even the stance of the body—and it’s so unexpected in the telling of the story of David and Goliath! I would expect rather a triumphal victorious figure, maybe holding the sword and the enemy’s severed head aloft… Instead, here is a thoughtful, quiet, contemplative face.

BH: I don’t know, he doesn’t look so contemplative to me—instead he seems proud of his victory over the giant Goliath—which is strange since the story is very much about how David defeats Goliath because he has God’s help—he doesn’t do it on his own!

SZ: Really? Look at his calm, downcast eyes… the lids are half closed. That is not the usual expression of victory. Note that the facial muscles are totally relaxed, the mouth is lightly closed though there is the slightest hint of a smile—and yes, that is subtle pride, but to me this is the face of interior thought not exterior boasting. It’s as if he is coming to terms with the events that have taken place, including God’s intervention, here Donatello foreshadows the wisdom that will define his later reign as king.

BH: Fair enough, perhaps it’s primarily his pose that speaks of pride to me. The relaxed contrapposto and the placement of his left hand nonchalantly on his hip feels to me like confidence and pride. His right hand holds the sword that he used to cut off Goliath’s head, which we see below, resting on a victory wreath. The gruesome head seems to conflict with the sensuality and beauty of the young David.

SZ: Agreed. There is a certain swagger in that stance and the horrific contrast to the head of Goliath is wild and unnerving. But the contrapposto is also Donatello’s swagger, the sculptor’s rendering of David offers the most complete expression of this natural stance since antiquity. We know he was studying ancient Roman art with his friends, Masaccio and Brunelleschi and it’s worth noting that he reclaims more than just the classical knowledge of contrapposto, he has also reclaimed the large-scale bronze casting of the ancient world. It must have been such an extraordinary revelavation for a culture that until this moment, had not seen human-scaled bronze figures.

BH: It IS amazing how Donatello, after a thousand years, reclaims the ancient Greek and Roman interest in the nude human body. Of course, artists in the middle ages, a period when the focus was on God and the soul, rarely represented the nude. Donatello does so here with amazing confidence, you’re right. In fact, this is the first free-standing nude figure since classical antiquity, and when you consider that, this achievement is even more remarkable! But let’s face it, there’s an undeniable sensuality here that almost makes us forget that we’re looking at an old testament subject.

SZ: Right, Donatello’s figure of David is almost too sensuous for the subject being represented. In some sense this isn’t really a Biblical representation at all; Donatello seems to have used the excuse of the boy who eschews armor in order to represent not the Judaic tradition but instead the ancient Greek and Roman regard for the beauty of the human body and he uses the classical technique of lost wax to cast the form. Then, just like the Greeks and Romans, he worked the bronze to smooth the seams and the surface and to cut in details such as in the hair.

BH: I think it’s important to stress that this figure is free-standing. Sculpted figures have finally been detached from architecture and are once again independent in the way they were in ancient Greece and Rome. And because he’s free-standing, he is more human, more real. He seems able to move in the world, and of course the contrapposto does that too. It’s easy to imagine this figure in the Medici palace garden, surrounded by the ancient Greek and Roman sculpture that they were also collecting. I wish I could go back in time to Florence in the 1400s, to this remarkable moment, to witness the rebirth of Humanism.

SZ: I’d love to meet the artists and thinkers of the era but am not at all sure that I would find their world hospitable. Disease, want, cruelty, and a permanent hierarchy among social strata defined the period—not to mention the terrible position women found themselves in. You can go, I’ll stay here in the 21st century thank you!

BH: Like David, Florence was the underdog that withstood repeated attacks from Milan and yet, like young David, thanks to God’s favor, Florence was victorious (or at least that’s how the Florentines interpreted these events!). And as a result, many Florentine artists will tackle this subject.

SZ: True, and each one will have to grapple with Donatello’s great achievement.

David and Goliath

The subject of this sculpture is David and Goliath, from the Old Testament. According to the story, Israel (the descendents of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob) is threatened by Goliath, a “giant of a man, measuring over nine feet tall. He wore a bronze helmet and a coat of mail that weighed 125 pounds.” Goliath threatened the Israelites and demanded that they send someone brave enough to fight him. But the entire Israelite army is frightened of him. David, a young shepherd boy, asserts that he is going to fight the giant, but his father says, “There is no way you can go against this Philistine. You are only a boy, and he has been in the army since he was a boy!” But David insists that he can face Goliath and claims he has killed many wild animals who have tried to attack his flock, “The LORD who saved me from the claws of the lion and the bear will save me from this Philistine!” They try to put armor on David for the fight, but he takes it off. David faces Goliath and says to him,”You come to me with sword, spear, and javelin, but I come to you in the name of the LORD Almighty—the God of the armies of Israel, whom you have defied.” David kills Goliath with one stone thrown from his sling into Goliath’s forehead. Then he beheads Goliath.

The people of Florence identified themselves with David—they believed that (like him) they defeated their enemy (the Duke of Milan) with the help of God.

Additional resources:

David by Donatello, Palazzo Medici

Monumental Sculpture from Renaissance Florence: Ghiberti, Nanni di Banco, and Verrocchio at Orsanmichele, National Gallery of Art

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Donatello, Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Donatello, Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata (Erasmo da Narni), 1445-53, bronze, 12′ 2″ high, Piazza del Santo, Padua

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Donatello, Mary Magdalene

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Donatello, Mary Magdalene, c. 1455, wood, 188 cm (Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Leon Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti, Palazzo Rucellai

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Leon Battista Alberti, Palazzo Rucellai, c. 1446-51, Florence (Italy)

Humanist architecture for a private home

By 1450, the skyline of Florence was dominated by Brunelleschi’s dome. Although Brunelleschi had created a new model for church architecture based on the Renaissance’s pervasive philosophy, Humanism, no equivalent existed for private dwellings.

In 1446, Leon Battista Alberti, whose texts On Painting and On Architecture established the guidelines for the creation of paintings and buildings that would be followed for centuries, designed a façade that was truly divorced from the medieval style, and could finally be considered quintessentially Renaissance: the Palazzo Rucellai. Alberti constructed the façade of the Palazzo over a period of five years, from 1446-1451; the home was just one of many important commissions that Alberti completed for the Rucellais—a wealthy merchant family.

Three tiers

Like traditional Florentine palazzi, the façade is divided into three tiers. But Alberti divided these with the horizontal entablatures that run across the facade (an entablature is the horizontal space above columns or pliasters). The first tier grounds the building, giving it a sense of strength. This is achieved by the use of cross-hatched, or rusticated stone that runs across the very bottom of the building, as well as large stone blocks, square windows, and portals of post and lintel construction in place of arches.

The overall horizontality of this façade is called “trabeated” architecture, which Alberti thought was most fitting for the homes of nobility. Each tier also decreases in height from the bottom to top. On each tier, Alberti used pilasters, or flattened engaged columns, to visually support the entablature. On the first tier, they are of the Tuscan order. On the second and third tiers, Alberti used smaller stones to give the feeling of lightness, which is enhanced by the rounded arches of the windows, a typically Roman feature. Both of these tiers also have pilasters, although on the second tier they are of the Ionic order, and on the third they are Corinthian. The building is also wrapped by benches that served, as they do now, to provide rest for weary visitors to Florence.

The Palazzo Rucellai actually had four floors: the first was where the family conducted their business; the second floor, or piano nobile, was where they received guests; the third floor contained the family’s private apartments; and a hidden fourth floor, which had few windows and is invisible from the street, was where the servants lived.

The loggia

In addition to the façade, Alberti may have also designed an adjacent loggia (a covered colonnaded space) where festivities were held. The loggia may have been specifically built for an extravagant 1461 wedding that joined the Rucellai and Medici families. It repeats the motif of the pilasters and arches found on the top two tiers of the palazzo. The loggia joins the building at an irregularly placed, not central, courtyard, which was probably based on Brunelleschi‘s Ospedale degli Innocenti.

The influence of ancient Rome

In many ways, this building is very similar to the Colosseum, which Alberti saw in Rome during his travels in the 1430s. The great Roman amphitheater is also divided into tiers. More importantly, it uses architectural features for decorative purposes rather than structural support; like the engaged columns on the Colosseum, the pilasters on the façade of the Rucellai do nothing to actually hold the building up. Also, on both of these buildings, the order of the columns changes, going from least to most decorative as they acend from the lowest to highest tier.

The Palazzo Rucellai has many features in common with the Palazzo Medici (below), which was constructed a few years before, not far from Alberti’s building. The Palazzo Medici is also divided into three horizontal planes that decrease in heaviness from bottom to top.

But there are subtle differences that betray the intents of the patrons. The bottom tier of the Palazzo Medici, built for Cosimo il Vecchio de’ Medici by Michelozzo, resembles the stone of the Palazzo Vecchio (left), the seat of political power of Florence, with which Cosimo intentionally wanted to associate himself. It also employs the same type of windows.

Because Michelozzo used this medieval building as a model, whereas Alberti looked to ancient Rome, the Palazzo Medici is not truly Humanist in its conception and lacks the geometric proportion, grace, and order of the Palazzo Rucellai. The top tier of the Palazzo Medici is almost entirely plain, whereas Alberti continued to use architectural features for ornamentation throughout his design.

The main difference between the Palazzo Rucellai and other palazzi was Alberti’s reliance on ancient Rome. This may have reflected Giovanni Rucellai’s pretensions for his family. Rome was the seat of the papacy, and though Rucellai was not a cleric, he claimed to have descended from a Templar. The Palazzo Rucellai went on to influence the design for the homes of many clerics, such as the famous Palazzo Piccolomini that was built for Pope Pius II in Pienza by Bernardo Rossellino.

Text by Christine Zappella

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Alberti, Façade of Santa Maria Novella, Florence

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Alberti, Façade of Santa Maria Novella, Florence, 1470.

Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Leon Battista Alberti, Sant’Andrea in Mantua

by DR. HEATHER HORTON

Mantua’s relic

In the fifteenth century, pilgrims flocked to the Basilica of Sant’Andrea to venerate the most famous relic in the city of Mantua: drops of Christ’s blood collected at the Crucifixion, or so the faithful believed. In fact, the church Sant’Andrea was erected to accommodate the huge crowds that arrived on holy days and who, in turn, helped fund its construction. Today, art historians admire Sant’Andrea’s Early Renaissance design for elegantly bringing the grandeur of ancient architecture into a Christian context.

Who built that?

Sant’Andrea is built of bricks, though they are mostly concealed by painted stucco. The patron, Ludovico Gonzaga, estimated that at least two million bricks were needed. The bricks were baked in onsite kilns, making the church far less expensive and faster to erect than a building made with stone, which had to be quarried, transported, and finished.

Gonzaga was the Marquis of Mantua—and in addition to employing Alberti, he appointed Andrea Mantega as court artist. His portrait is featured in the frescos Mantegna painted in the Camera degli Sposi (also known as the Camera Picta), in the Marquis’ palace.

The sections of the building constructed in the Fifteenth Century, including the Western façade and the nave up to the transept, are usually attributed to the humanist and architect Leon Battista Alberti, even though he died in Rome a few months before construction began in June 1472. Alberti was an expert on all things ancient and he wrote the first Renaissance architectural treatise.

Alberti probably made a model to explain his design and he definitely sent Gonzaga a drawing (now lost), and a short description of his plan in a letter dated 1470. Despite this, it is uncertain how much of the building follows Alberti’s design, how much comes from the Florentine architect Luca Fancelli who directed construction, and how much should be credited to Gonzaga, who closely supervised the project.

Ancient models

Questions of Sant’Andrea’s attribution are important because it is such an ingenious, unified combination of three ancient Roman forms: temple front, triumphal arch, and basilica.

On the façade, four giant pilasters with Corinthian capitals support an entablature and pediment.

Together these elements recall the front of ancient temples, such as the Pantheon in Rome. There is also a grand arch in the center of the façade that is supported, at least visually, by two shorter fluted pilasters. Taken together, the lower façade, with its tall central arch and flanking side doors evoke ancient triumphal arches such as the Arch of Constantine.

Ancient rituals

The center arch extends deep into the facade itself, creating a recessed barrel vault that frames the main entrance to the church. The arch and its coffered barrel vault form a perfect setting for processions of the holy relic and the celebration of Christ’s triumph over death. Such spectacles would recall ancient processions where victorious warriors paraded through Rome’s triumphal arches.

When pilgrims pass under the arch and into the nave (the long interior hall), after their eyes adjusted to the purposefully dim, mystical light, they would look up and see a second, much more massive barrel vault, the largest constructed since ancient Rome.

Then, on both sides of the nave they would find three chapels with lower barrel vaults. Surprisingly, there are no side aisles or rows of columns, as at the old St. Peter’s in Rome or other early churches like Santa Sabina.

Sant’Andrea’s huge central space and buttressing side chapels strongly resemble the layout of the ancient Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine in the Roman forum (below). The basilica plan is perfectly suited to large churches since it could accommodate massive crowds. But unlike earlier basilica-plan churches, Sant’Andrea’s plan seems to return more strictly to the ancient forms.

It’s even possible that Sant’Andrea’s unusual plan and all’antica (“after the antique”) façade impacted the new St. Peter’s and the Church of the Gesù in Rome.

Northern Italy: Venice, Ferrara, and the Marches

Venetian painting is characterized by deep, rich colors and a strong interest in the effects of light.

1400 - 1500

Beginner’s guide: Venice in the 15th century

Venice is a cluster of islands, connected by bridges and canals.

1400 - 1500

Venice was a very wealthy city, with a strong merchant class that helped shape its culture. Ships from the East brought luxurious, exotic pigments, while traders from Northern Europe imported the new technique of oil painting. Since oil dries slowly, the colors could be blended together to achieve subtle gradations.

Venetian art, an introduction

by DR. HEATHER HORTON

Venice – another world

Petrarch, the fourteenth-century Tuscan poet, called Venice a “mundus alter” or “another world,” and the city of canals really is different from other Renaissance centers like Florence or Rome.

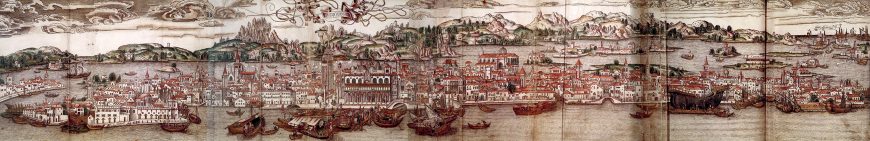

Venice is a cluster of islands, connected by bridges and canals, and until the mid ninteenth century the only way to reach the city was by boat. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Venice suffered numerous outbreaks of the plague and engaged in major wars, such as the War of the League of Cambrai. But it also boasted a stable republican government led by a Doge (meaning “Duke” in the local dialect), wealth from trade, and a unique location as a gateway between Europe and Byzantium.

The Venetian Style

Painting in Early and High Renaissance Venice is largely grouped around the Bellini family: Jacopo, the father, Giovanni and Gentile, his sons, and Andrea Mantegna, a brother-in-law. Giorgione may have trained in the Bellini workshop and Titian was apprenticed there as a boy.

The Bellinis and their peers developed a particularly Venetian style of painting characterized by deep, rich colors, an emphasis on patterns and surfaces, and a strong interest in the effects of light.

While Venetian painters knew about linear perspective and used the technique in their paintings, depth is just as often suggested by gradually shifting colors and the play of light and shadow. Maybe Venetian painters were inspired by the glittering gold mosaics and atmospheric light in the grand Cathedral of San Marco, founded in the 11th century? Or maybe they looked to the watery cityscape and the shifting reflections on the surfaces of the canals?

Oil paint

The Venetian trade networks helped to shape local painting practices. Ships from the East brought luxurious, exotic pigments, while traders from Northern Europe imported the new technique of oil painting. Giovanni Bellini combined the two by the 1460’s-70’s. In the next few decades, oil paint largely supplanted tempera, a quick-drying paint bound by egg yolk that produced a flat, opaque surface. (Botticelli’s Birth of Venus is one example of tempera paint, which you can learn more about here).

To achieve deep tones, Venetian painters would prepare a panel with a smooth white ground and then slowly build up layer-upon-layer of oil paint. Since oil dries slowly, the colors could be blended together to achieve subtle gradations. (See this effect in the rosy flush of the Venus of Urbino’s cheeks by Titian or in the blue-orange clouds in Giorgione’s Adoration of the Shepherds—above). Plus, when oil paint dries it stays somewhat translucent. As a result, all of those thin layers reflect light and the surface shines. Painting conservators have even found that Bellini, Giorgione, and Titian added ground-up glass to their pigments to better reflect light.

Venetian painting in the 16th century

Over the next century Venetian painters pursued innovative compositional approaches, like asymmetry, and they introduced new subjects, such as landscapes and female nudes. The increasing use of pliable canvas over solid wood panels encouraged looser brushstrokes. Painters also experimented more with the textural differences produced by thick versus thin application of paint.

In the Late Renaissance Titian’s mastery was rivaled by Tintoretto and Veronese. Each attempted to out-paint the other with increasingly dynamic and sensual subjects for local churches and international patrons. (Phillip II of Spain was particularly enamored with Titian’s mythological nudes.) The trio transformed saintly stories into relatable human drama (Veronese’s The Dream of St. Helena), captured the wit and wealth of portrait subjects (Titian’s Portrait of a Man), and interpreted nature through mythological tales (Tintoretto’s The Origin of the Milky Way).

Additional resources:

Sacra Conversatione from The National Gallery

Titian on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art History

Madonna of the Pesaro Family from the University of Mary Washington

Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, and the Renaissance of Venetian Painting

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Oil paint in Venice

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): A review of fresco and tempera and the development of the use of oil paint by artists in Venice.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Ca’ d’Oro

Venice, an outlier

When we think of the Italian Renaissance, we think of cities like Florence, Siena, and Milan where artists took an interest in reviving the traditions of classical antiquity. Venice, in contrast, remained something of an outlier. Whereas Florence, Siena, and Milan recalled their Greco-Roman past, Venice looked to its Byzantine history (as part of the eastern Roman Empire), which extended from the classical period up through the more recent medieval era.

Other Italian cities were also embroiled with political unrest even well into the High Renaissance (beginning in the late fifteenth century); rivaling families vied for power, warring for control, and killing or imprisoning their enemies. Venice’s more stable political climate and defensible island setting made it different from the other major cities in fifteenth-century Italy.

Venice’s unique position also made for a unique architecture. By the fifteenth century, it was a very wealthy city, with a strong merchant class that helped shape its culture. The city’s wealthiest families had the means and desire to build impressive palaces for themselves in the tradition of prominent civic architecture such as the fourteenth-century Palazzo Ducale on St. Mark’s Square. These powerful patrons constructed buildings as a way to express their wealth and importance and the Ca’ d’Oro (above) is a perfect example.

House of gold

Bartolomeo and Giovanni Bon are credited with the decoration for the Ca’ d’Oro, built for Marin Contarini, of the prominent Contarini family. The building borrows its style from the Palazzo Ducale (the palace of the elected ruler of Venice), albeit on a smaller scale, but what it loses in size it makes up for in ornamentation. The building was known as the Ca’ d’Oro—“House of Gold”—because its façade originally shimmered with gold leaf, which has since faded away. You can’t get much more opulent than a golden house! Even with the gold leaf no longer in place, it is still possible to get a good sense of the richness of this gem of a building.

Like the Palazzo Ducale, the Ca’ d’Oro is much more open than many of the palaces built in other parts of Italy at this time. Unlike the Palazzo Medici in Florence, for example, the Ca’ d’Oro is not fortress-like structure built with massive rusticated stones.

Also like the Palazzo Ducale, it is divided into three distinct stories: a lower loggia (covered corridor) of pointed arches open to the water, a middle balcony with a balustrade (railing) and quatrefoils (four-lobed cutout), and a top balcony with another balustrade and fine stone openwork.

The result is a delicate, ornate building that seems almost like a work of sculpture. Each level of the façade is increasingly ornate and intricate towards the top. The increased ornamentation on each story creates a vertical emphasis; however, that verticality is matched by the equally strong horizontal emphasis provided by the two balustrades on the upper balconies and the large cornice at the roofline.

We also see a precise harmony to the division of space. The lower loggia has a wide arch at its center, which is symmetrically flanked by narrower arches. In the balcony above, two arches fit in the space directly above the wide central arch of the lower loggia.

The arrangement of columns and arches in the upper two balconies perfectly corresponds with one another: column over column, arch over arch. The façade’s harmonious arrangement suggests the architects in Venice had similar interests to those of the classicizing architects working in Florence.

Uniquely Venetian

Yet, we cannot describe the Ca’ d’Oro simply in terms of Renaissance palace architecture. It is a distinctly Venetian building in its incorporation of Byzantine, Islamic, and Gothic elements. This blending together of architectural styles in a uniquely Venetian style had already occurred in the Palazzo Ducale, but this is perhaps an even better example of that phenomenon.

Patterned colored stones, in the tradition of Byzantine architecture, fill the flat wall space of the façade. As in the Palazzo Ducale, the ornamental details on the arcade and balconies combine Islamic and Gothic elements. In the Ca’ d’Oro, though, the ornamentation pops because of its intense detail, set within the patterned stone walls. All of the different forms of ornament are combined within the same area of the façade.

The five Gothic quatrefoils of the second story balcony stand atop slender columns. They stand out as distinct sculptural elements carved on all sides. In the upper balcony, pointed arches borrow from Islamic architecture in their distinct horseshoe shape and from Gothic architecture in their elongated, pointed form. Tracery connects every other column, creating an elegant interwoven effect. Within that interweaving, smaller pointed arches connect neighboring columns to one another, and these arches are multi-lobed, also in the tradition of Islamic architecture. Above each column there is a delicate cutout that mimics the quatrefoils in the level below. The open carving of the upper balconies in fact resembles the ornate screens common in Islamic architecture. This is repeated in the ornamentation of the windows to either side of the balcony on the second story.

In spite of its complexity and its many sources of inspiration, the building is unified and neither over-the-top nor visually chaotic. The Ca’ d’Oro’s varied elements come together in spectacularly unique fashion. The building embodies a distinct architecture all its own in early Renaissance Venice, one not merely imitative of Byzantium, the Gothic North, or Islam. Venetian architects brought these different elements together in new and surprising ways, making a building such as the Ca’ d’Oro tremendously important.

Additional resources:

This building at the Venetian Ministry of Cultural Heritage

Palazzo Ducale

Venice in the 14th century

Today, we think of Italy as a unified country. But in the fourteenth century, the major urban centers of Italy were largely unstable. Wars were common. Rivaling families sought to oust their opponents—often by violent means—and seize power for themselves. This is why so much civic architecture of the Renaissance period is imposing and fortress-like. Buildings like Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio (below)—with its thick, tall walls and defensive crenellations (gaps at the top of the wall for shooting)—were the standard for civic buildings in Italy well into the fifteenth century.

Things were different in Venice. The city was politically more stable than other Italian centers, and it was also naturally protected from invasion by its favorable setting in a lagoon on the Adriatic Sea. As a result, Venice’s architecture did not need to be as defensive as the architecture of neighboring regions. This allowed for greater experimentation in architectural form evident in the Palazzo Ducale, constructed beginning in 1340, for the elected ruler of Venice.

A new palace for the doge

Fourteenth-century Venice was an oligarchy, meaning that it was ruled by a select group of elite Venetian merchants. The main elected ruler was called the “doge,” and his residence was—much like the White House in the United States—a private residence and also a place for official business. Although there was already a residence for Doge Gradenigo in the 1340s, the system of government changed afterwards so that more people were involved in governmental activities. This required more space than was available in the existing palace, the great council (a political body consisting of the nobility) voted to extend the palace. Workers began construction in 1340 and continued into the early part of the fifteenth century.

The Palazzo Ducale sits in a prominent location. It is adjacent to the Basilica of St. Mark (Venice’s cathedral church), on St. Mark’s Square. The Ducale also overlooks the lagoon, which was a major point of entry into the city. Its prominent location made it (and continues to make it) an important symbol of Venetian architecture. It offered visitors one of their first impressions of the city.

Delightfully open

The building appears delightfully open and ornamental precisely because it is able to forego many elements of defensive architecture. The façade includes three levels: a ground-level loggia (covered corridor) defined by an arcade of pointed arches. The second level contains an open balcony which features a prominent balustrade (railing) that divides the first and second stories.

Like the lower loggia, the balcony features pointed arches, though here with the addition of delicate quatrefoils (four-lobed cutouts) just above them.

A stone wall completely encloses the third and uppermost level of the façade and is punctuated by a row of large, pointed windows.

In many respects—especially in its horizontal emphasis and three-story façade—the exterior of the Palazzo Ducale exhibits features that emerged in the Renaissance architecture of Florence during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. One could argue that this building anticipates those trends. Undoubtedly, in the Palazzo Ducale, we see a degree of the harmony and rhythm that we associate with later Italian Renaissance architecture.

Crossroads of Byzantium, Islam, and Gothic Europe

However, the Palazzo Ducale is actually more representative of the unique position of Venice in the fourteenth century. Venice occupied a geographical location that was inherently defensible, and the city was uniquely situated in terms of its proximity to other cultures. Venice once belonged to the Byzantine Empire (the eastern part of the Roman Empire), but by the fourteenth century, it was an independent republic. Yet, it still had strong cultural and artistic links to Byzantium, partially because Venice was a robust center of trade with the East. The city absorbed many of the traditions of Islamic art and culture by virtue of contact with Islamic traders, artisans, and goods. Similarly, Venice’s location at the northern edge of the Italian peninsula meant that it was closer to the Gothic centers of northern Europe than Italian cities farther to the south, such as Florence. It took longer to shake the Gothic habit, so to speak.

We see the architectural heritage of each of these distinct cultures in the Palazzo Ducale. The upper story of the façade features a diamond pattern of colored stone, a technique that was a hallmark of late Byzantine architecture. The openwork (lattice-like carving) and arcades of the bottom two levels combine Islamic and Gothic influences. Pointed arches and quatrefoils were typical features on Gothic buildings, but the pointed arches bow out beneath their peaks, in the manner of Islamic horseshoe arches. We also see tripartite lobes within the arches of the balcony that resemble a similar trend in Islamic architecture. As a result of its unique cultural and geographic position, fourteenth-century Venetian architecture—as exemplified by the Palazzo Ducale—is a beautiful hybrid of Byzantine, Islamic, and Gothic cultures, which are all bound together within a blossoming Venetian Renaissance architectural tradition.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Devotional confraternities (scuole) in Renaissance Venice

Venetian Society and the scuole

The Republic of Venice lasted for almost one thousand years (from the eighth to the eighteenth century). Its exceptional stability was due not only to its geographical position (in the middle of a protective lagoon) and its effective political system, but also to its social structure and the stabilizing presence of the scuole.

The scuole were confraternities, or brotherhoods, founded as devotional (religious) institutions, that were set up with the purpose of providing mutual assistance. They provided an important guarantee against poverty and played a crucial role in protecting individuals and families in need. The scuole were supported by a tax levied on each member and on the bequests of wealthy brothers. These donations and earnings were then used to help all the members and their families. The scuole also depended on the state, which exercised a protective and supervisory role. Each scuola had a patron saint and a statute with its own symbols and emblems.

In the fifteenth century, more than two hundred such scuole existed, among which six were scuole grandi (large scuole). By then the initial religious role had shifted to a more civic purpose. The scuole grandi included individuals who had diverse occupations and could afford spectacular meeting-houses, while the scuole piccole (small scuole), could be purely corporate. Even foreigners, in order to overcome the lack of protection by the State, and to strengthen their national or religious identity, founded several scuole piccole. These were all dissolved (but one) with the Napoleonic invasion in 1797—the year that marked the end of the Venetian Republic.

Social structure

In Venice there were three distinct social classes:

Patricians

The patricians were drawn from the nobility and were the ruling class. They represented about 5 percent of the population and were the only ones eligible to hold positions at a high political level.

Citizens

The next 5 percent were known as citizens. Citizens were divided into two categories: those who were Venetian by birth and those who became citizens after a lengthy process of naturalization (similar to green card status in the United States). Professionals, employees of the bureaucracy and merchants usually qualified as citizens. Though Citizens did not hold political power, they could exert some influence through the scuole, where the most distinguished members held significant positions.

Working class

The working class included artisans, small traders, other workers, and seamen. These people were not necessarily poor, just as the patricians were not necessarily rich. The working class also had their own scuole.

The Teleri

The scuole served an important role in the patronage of Venetian art. Along with altarpieces, they commissioned large narrative painting cycles (teleri). The subject matter of the teleri (telero — singular) was always religious but they also carried secular and civic connotations. The charm of these large paintings lies in the fact that they tell stories that unfold step by step. Because the imagination of the artists and their narrative skill was combined with their patron’s instructions—and there are even instances when members of a scuola required they were included in the paintings, teleri provide a fascinating visual journey that allows us to appreciate and understand Renaissance Venice. What follows are a few outstanding examples with brief descriptions.

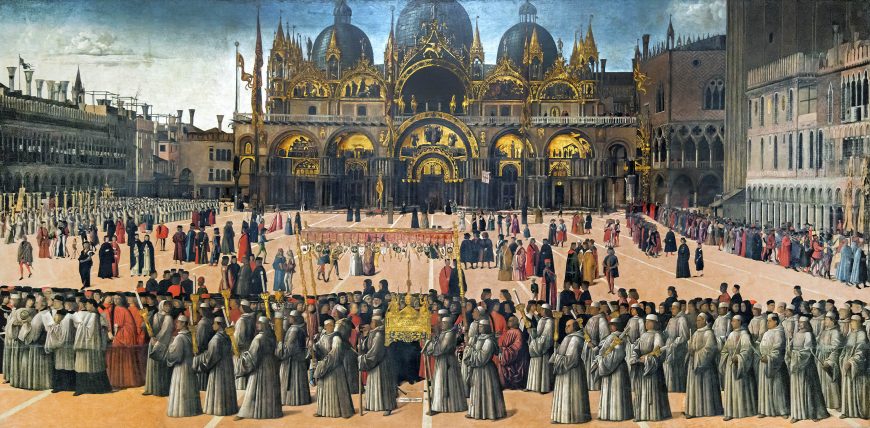

Gentile Bellini, Procession in St Mark’s Square, 1496

The Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista (a large scuola dedicated to St. John the Evangelist) commissioned paintings that narrate the miracles made by the relic of the True Cross that was in its possession. This sacred fragment was carried through the streets of the city each year on April 25 for the feast of St. Mark (patron saint of the city). In Venice, processions had great civic and religious meaning; creating continuity season after season, virtually unchanged over time.

This painting, by the great Venetian artist Gentile Bellini, depicts a miracle. In the midst of the procession, in the foreground, is a man in prayer. He is a merchant from Brescia who, having arrived in Venice for business, received the terrible news that his beloved son was in critical condition from a blow to his head. The next day, the man, aware of the powers of the True Cross, went to attend the ceremony, and when the famous relic passed in front of him, he knelt before it as a sign of devotion. When he returned home, he found his child miraculously healed.

The protagonists of the procession are in the foreground: the scuola’s brothers (members) are dressed in white; the procurators (the office of procurator of St Mark’s was the second most prestigious appointment in the Venetian government after that of Doge) and senators of the Republic wear red gowns. The patricians and the citizens wear black. The members of the scuola carry a canopy to protect the reliquary that holds the sacred relic as it is carried through St. Mark’s Square (the religious and political heart of the city).

St. Mark’s Square is reproduced in Bellini’s painting with a wide-angle view in striking detail, providing a remarkable visual document of the square at the end of the fifteenth century. To open up the scene, the artist moved the bell tower to the right. St. Mark’s Basilica, sparkling with its Byzantine gold (gold also lights up the reliquary in the foreground), functions as a backdrop. The square is populated by a cosmopolitan mix of people elegantly dressed in the fashion of the time: some young people in multicolored stockings, a group of Jews, a number of Turks wearing turbans, as well as merchants and children. On the left, women look out from the windows and colorful carpets are displayed from balconies as a sign of celebration.

Vittore Carpaccio, The Healing of the Madman, 1496

Carpaccio portrayed another miracle of the True Cross for the Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista. The artist presents the passage of the miracle from the procession on the bridge (whose members are in white) to the main event that takes place in the Patriarch of Grado’s palace on the upper left. The Patriarch is seen raising the relic before a possessed man who fixes a glassy-eyed stare on it, and who will be miraculously cured. The miracle is in progress, a dramatic moment made even more authentic by the fact that the scene takes place in a marginal position within the composition. The white tunics of the procession members surround the scene, while all around life unfolds quietly, and it seems that few are aware of what is happening. Here Venice itself is not just the background but a dominant theme of the painting.

One can see the Rialto Bridge (the financial heart of the city) as it was then, constructed in wood, with a row of shops on each side, while below the Grand Canal (the main waterway of the city) is animated by gondolas and their gondoliers. In the distance, among the colorful palaces and the characteristic chimneys, daily life is in full swing. A woman beats a carpet, another hangs the laundry, a mason fixes a roof. In the lower section several men in turbans confirm the diversity of those who visited the Rialto market.

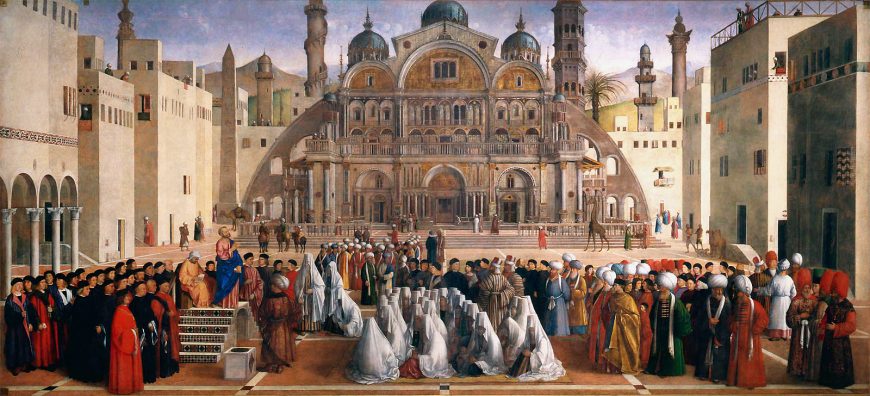

Gentile Bellini, St Mark Preaching in Alexandria, Egypt, 1504-07

The Scuola Grande di San Marco commissioned Gentile Bellini to paint St. Mark Preaching in Alexandria, Egypt, but the artist died before the painting was completed, so it was finished by his brother Giovanni Bellini (who, like Gentile, had never been to Alexandria). For the costumes and architectural details, Gentile drew inspiration from his stay in Constantinople and from travelers’ accounts. The layout of the painting is reminiscent of Procession in St. Mark’s Square, where the figures in the foreground are represented in profile.

The saint, who will become the patron saint of Venice, preaches from a small podium placed between the scuola brothers and the Arabs, while in the background stands a great temple whose façade, divided into three parts, brings to mind the meeting house of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, the Basilica of San Mark and the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. Nearby is an obelisk engraved with hieroglyphics and several minarets. In the square, alongside the inhabitants, a number of exotic animals stroll by, including camels and giraffes.

Vittore Carpaccio, Arrival of the Ambassadors, 1490-96

At the end of the fifteenth century, Vittore Carpaccio was commissioned by the Scuola Piccola di Sant’Orsola (a small scuola dedicated to Saint Ursula) to paint a cycle of nine paintings on the Life of Saint Ursula, taken from the popular medieval book, the Golden Legend by Jacopo da Varagine. With his vivid imagination he had no difficulty creating a northern scene (Brittany and Germany) set in the fourth century, often with elements drawn from an imaginary city reminiscent of fifteenth-century Venice. In the story, the ambassadors approached the father of Ursula in Brittany asking for the hand of his daughter on behalf of the English prince Ereo. After consulting her father, the girl accepted, on the condition that Ereo be baptized at the end of a long pilgrimage to Rome. After the baptism, on the way back to Cologne, the married couple ran into the king of the Huns who fell in love with Ursula. She rejected the proposals of the bloodthirsty ruler, preferring death instead.

The story begins with the Arrival of the English Ambassadors, where we see a large room represented with no front walls, while in the background we see buildings in the Venetian style and details of city life. Carpaccio skillfully employs perspective while maintaining the frieze-like structure typical of Venetian narrative paintings. The telero includes two consecutive moments. The first episode displays the ambassadors approaching the king; this scene unfolds behind a railing left accessible by an open gate. The following episode takes place in Ursula’s bedroom where she receives the message from her father. The room is simple but includes a devotional painting testifying to the pious character of the young girl.

Vittore Carpaccio, Saint George and the Dragon, 1502

Carpaccio was also summoned by the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni (Dalmatians) to depict the cycles of Saint George and Saint Jerome, still in-situ today. The cycle of Saint George is also taken from the Golden Legend. In the narrative, Selene, a city in Libya, was oppressed by a terrible dragon that fed off the meat of boys and girls and terrorized the town with threats of death and destruction. When it was the king’s daughter’s turn to be devoured, Saint George, on his steed, intervened swiftly, injured the dragon and then led it into the town before killing it in front of everyone. Thanks to the surprising liberation from the dragon, the knight persuaded the king and his people to be baptized.

In the combat scene with the dragon, the background is delineated to the left by a city, represented by several minarets, an obelisk, an equestrian statue, exotic palm trees and a castle typical of the Veneto (the region in northern Italy that was ruled by the city of Venice). On the other side we see the African princess, with a fair complexion and elegantly dressed in European-style clothing, looking on calmly, with her hands folded. In the foreground, the scene runs along the diagonal of the lance of Saint George who struggles valiantly with the dragon on a ground strewn with the remains of tortured bodies.

Conclusion

The complex narratives depicted in these paintings represent important religious events and miracles—yet directly or indirectly, they are simultaneously preoccupied with the complexity, diversity, and beauty of Renaissance Venice. They also point us to the critical role played by the scuole in both the life and art in the Most Sererene Republic of Venice.

Additional resources

Patricia Fortini Brown, Venetian Narrative Painting in the Age of Carpaccio (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998).

Gallerie dell’Accademia

Augusto Gentili, Le storie di Carpaccio (Venice: Marsilio,1996).

Peter Humfrey, Painting in Renaissance Venice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

Brian Pullan, Rich and Poor in Renaissance Venice: The Social Institutions of a Catholic State to 1620 (Oxford, 1971).

Brian Pullan, “The Scuole Grandi of Venice: Some Further Thoughts,” in Christianity and the Renaissance: Image and Religious Imagination in the Quattrocento, ed. T. Verdon and J.

Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni

Lorenza Smith, Venice: Art and History (Verona: Arsenale, 2011).

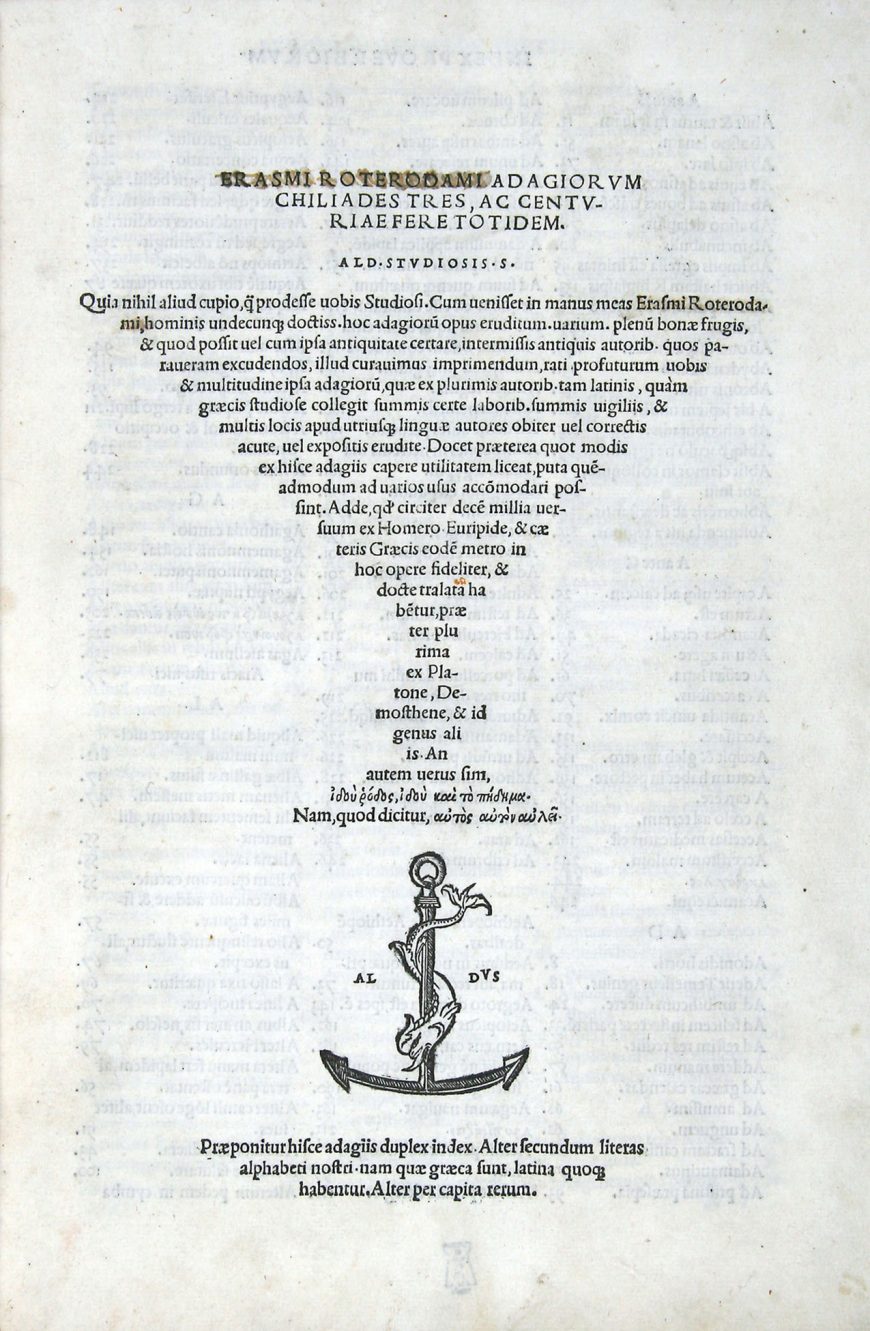

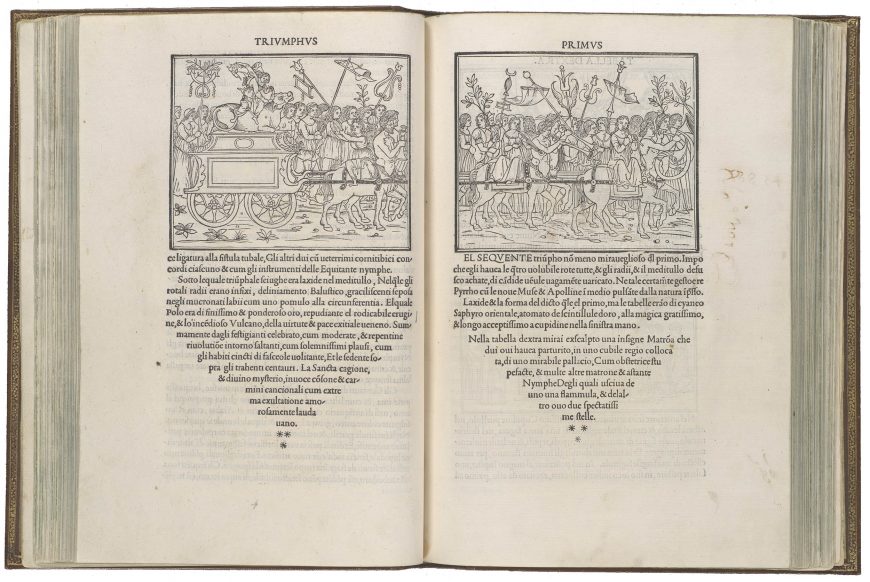

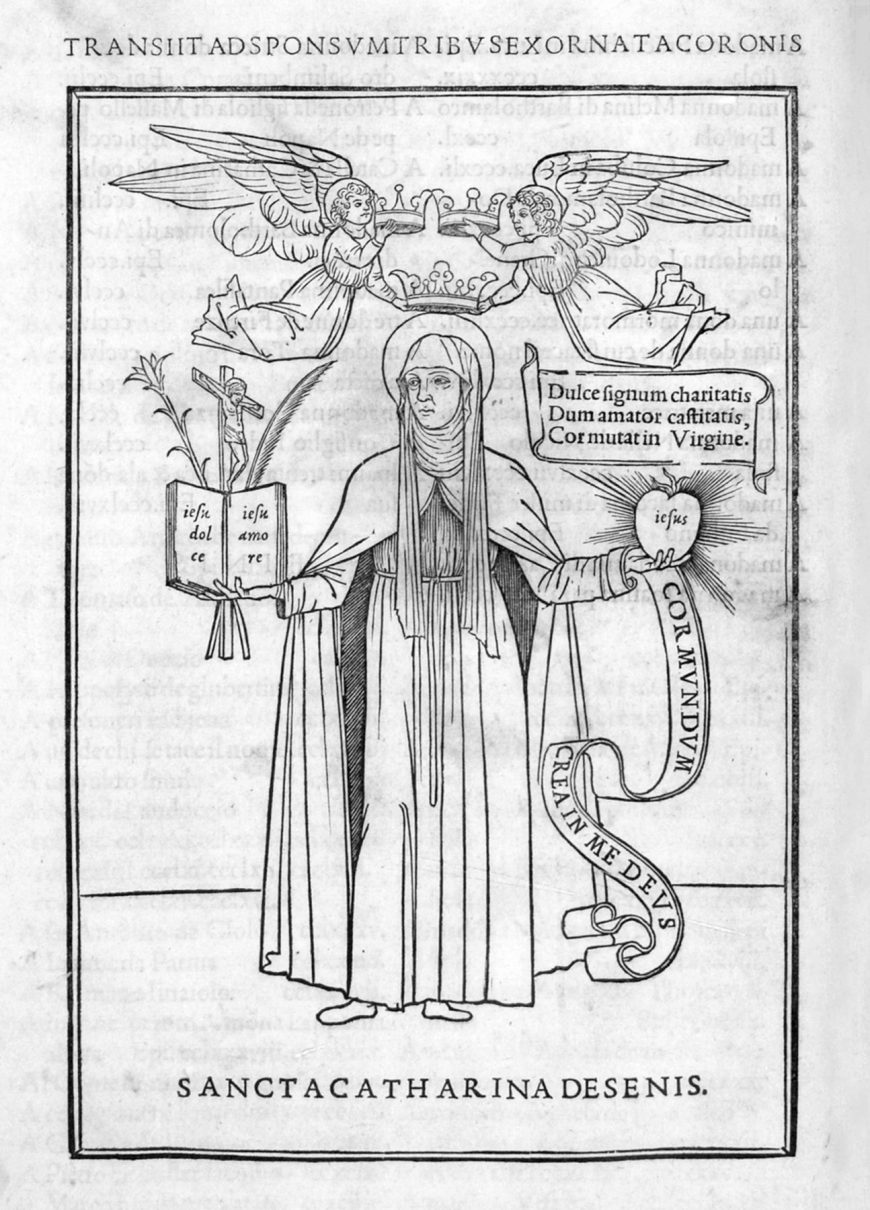

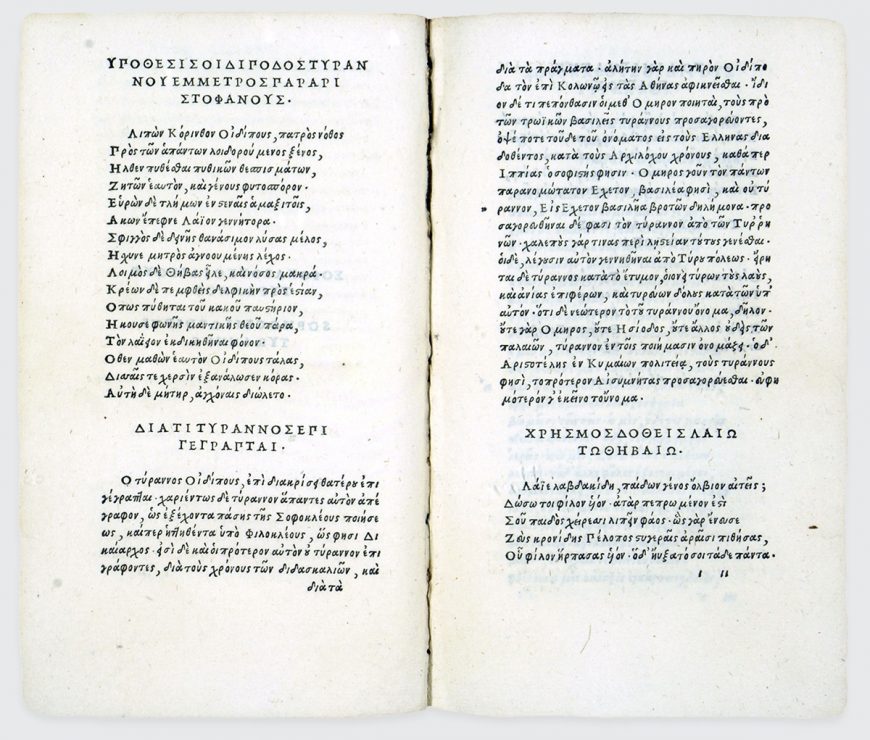

Aldo Manuzio (Aldus Manutius): inventor of the modern book

Venice as a center of print culture

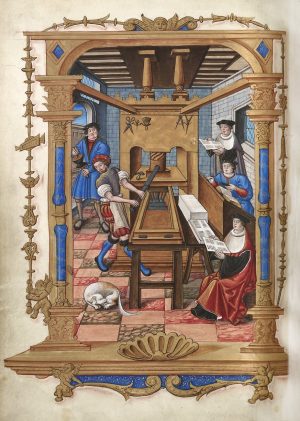

For centuries, Venice served as one of Europe’s main cultural and commercial centers and as the most important intermediary between Europe and the East. The city’s political stability and wealth, combined with its extensive international relationships and rich cultural and artistic life, proved to be fertile ground for the establishment of the printing press.

In the second half of the fifteenth century, when printed books gradually began to substitute for handwritten manuscripts, Venice was the European capital of the printing press. The invention of movable type in Germany in the mid-1400s ushered in a sea change, placing Venice on a par with modern-day Silicon Valley. Both of these creative environments resulted from a powerful combination of invention, technology and economic power. According to the scholar Vittore Branca, at the end of fifteenth century, an estimated 150 typographers operated in Venice, far more than the 50 or so that were active in Paris at that time. In the last five years of the century, Branca estimates that one-third of the volumes printed in the world originated from Venice.

Unsurprisingly, this flourishing industry generated wealth, cultural interest, and the diffusion of a new trend known as “bibliomania”—defined as a passionate enthusiasm for collecting and owning books. Readers and collectors from all over the world sought out the books of Venetian printers, who skillfully adapted production to demand. These printers created an inventory that was extraordinary in its variety, thanks also to the freedom of press granted by the government. It was in Venice that the first printed edition of the Koran was published, along with the first printed Talmud.

Books, booksellers, and bookstores

Anyone strolling through the bustling streets of Venice in the late 15th century would encounter bookstores whose windows displayed beautiful book frontispieces while catalogues of the books available either hung from the jamb of the door, or were available inside, on the counter. It was common practice for the bookseller to offer the loose pages of a book in a package which the buyer would subsequently arrange to have bound in accordance with his or her taste and financial means.

Bookstores soon became places where scholars, intellectuals, collectors, and book lovers gathered to discuss new editions, exchange information, and converse with the bookseller who often was also the publisher and the printer. The invention of movable type spawned an industry that led to the creation of a new professional figure, the printer-publisher, and a new business, the publishing house. The publishing house developed its own structure, investors, and also required legal advisors, due to the emergence of copyright issues.

Aldo Manuzio

“Venice is a place that is more similar to the rest of the world than to a city,” Aldo Manuzio wrote in a preface to one of his books. He arrived in Venice in 1490, driven by his profession as a Greek and Latin tutor. Manuzio was a humanist from a small town in central Italy, and it was probably his interest in books that brought him closer to the world of the printing press.

Manuzio was one of the first publishers in a modern sense. In a short time, he transformed the concept of the book in Europe thanks to his typographical innovations and to his unique editorial vision. He did this by founding and overseeing the Aldine Press, with the help of technicians, scholars, investors, as well as with political support. Aldine Press books were marked by a famous emblem depicting an anchor and dolphin and were known throughout the world for their accuracy, beauty, the superior quality of the materials employed, and their cutting-edge design.

Manuzio’s original intention was to spread Greek language and philosophy to a wider public. He subsequently produced books in Latin and Italian, publishing famous editions of Dante and Petrarch, as well as work by of some of his contemporaries, such as Erasmus. Over two decades Manuzio published 130 editions, 30 of which were first editions of Greek writers and philosophers.

Aldine editions stood out: from the first pages, Manuzio impressed the reader through the use of prefaces discussing his editorial work, his intentions and projects. In the preface, he would occasionally invite the reader to find and to report any errors in the text, thus actively engaging the reading public.

The inventor of the modern book

Many of the elements that Manuzio introduced, or eliminated, in the conception of his editions are innovations that have become embedded in today’s books. Notably, he gave a new look to the printed page: the pages of Manuzio’s books featured harmonic proportions between the size of the fonts, the printed section, and the white border, according to precise mathematical principles—reflecting a major theme in Renaissance culture.

Manuzio also introduced page numbers and made reading more fluid by clarifying the disorganized punctuation that prevailed at the time. He added a period at the end of the sentence and was among the first to adopt the use of the comma, apostrophe, accent, and semicolon in the ways they continue to be used today. In order to recreate the familiar effect of handwriting, he also invented what is now known in English as the “italic font,” named after it’s Italian provenance.

One of Manuzio’s most striking inventions was the printing of small-format books, the ancestors of our modern pocket-sized publications. Small religious volumes were already in circulation, but Manuzio’s revolutionary idea was to publish both classics and modern works in the small format.

It can be argued that through this innovation Manuzio also invented a new audience. With pocket-sized books, reading became an intimate moment, an activity that could be enjoyed while traveling, lying in bed, or sitting on a garden bench. For the first time, the book became a manageable, easy to carry, and relatively inexpensive object, therefore it became accessible to a larger audience comprised not only of scholars, but also of aristocrats and members of the upper middle class. The small books immediately became very fashionable and conferred a certain status, as we can see in many portraits of the time.

Sweeping away barbarism with books

The Aldine editions had a significant impact in Europe, imparting new momentum to the book market and creating a larger audience, that in turn stimulated culture and led to the spread of ideas. Erasmus praised Manuzio’s objective to “build a library that would have no boundary but the world itself.” Indeed, the power of a book is that it enables its readers to live many lives and to deepen their understanding of the entire world without ever needing to leave their homes. By reviving the classics and publishing modern works with rigor and beauty, Aldo Manuzio wished—in what has proven to be a timeless quote—that “it could be possible to defeat weapons with ideas and to sweep away barbarism with books.”

Additional resources:

Digital catalog for the Aldo Manuzio exhibition at the Gallerie dell’Accademia di Venezia

Guido Beltramini, Aldo Manuzio: il Rinascimento di Venezia (Marsilio, 2016)

Lodovica Braida, Stampa e cultura in Europa (Laterza, 2003)

Mario Brunetti, L’Accademia Aldina, in Rivista di Venezia, VIII, 1921

Carlo Dionisotti, Aldo Manuzio umanista e editore (Edizioni il Polifilo, 1995)

Gian Arturo Ferrari, Libro (Bollati Bolingheri, 2014)

Leonardas Vytautas Gerulaitis, Printing and Publishing in Fifteenth-Century Venice (American Library Association, 1976)

Paul Grendler, Schooling in Renaissance Italy: Literacy and Learning, 1300–1600 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989)

Mario Infelise, Aldo Manuzio: La costruzione del mito (Marsilio, 2016)

Mario Infelise, Manuzio, Aldo, il Vecchio, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani – Volume 69, Istituto dell’Enciclopedia italiana Treccani, 2007

Jill Kraye, The Afterlife of Aldus: Posthumous Fame, Collectors and the Book Trade (Warburg Institute, 2018)

Martin Lowry, The World of Aldus Manutius: Business and Scholarship in Renaissance Venice (Cornell University Press, 1979)

Aldo Manuzio, Humanism and the Latin Classics, edited and translated by John N. Grant (Harvard University Press, 2017)

Giovanni Mardersteig, Aldo Manuzio e i caratteri di Francesco Griffo da Bologna, in Studi di bibliografia e storia in onore di Tammaro De Marinis (1964)

Saving Venice

by LISA ACKERMAN and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): A conversation about the issues facing Venice and efforts to save the historic city, with Lisa Ackerman, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, World Monuments Fund and Steven Zucker

Additional resources:

Venice (from the World Monuments Fund)

Marcello Rossi, “Will a Huge New Flood Barrier Save Venice?” Wired Magazine, April 5, 2018

As Tourists Crowd Out Locals, Venice Faces ‘Endangered’ List (from NPR)

Robert C. Davis, Garry R. Marvin, Venice, the Tourist Maze: A Cultural Critique of the World’s Most Touristed City (University of California Press, 2004)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Carlo Crivelli

Carlo Crivelli, The Annunciation with Saint Emidius

Video \(\PageIndex{12}\): Carlo Crivelli, The Annunciation with Saint Emidius, 1486, egg and oil on canvas, 207 x 146.7 cm (The National Gallery, London)

Aside from Cosimo Tura, Carlo Crivelli was the most delightfully odd late Gothic painter in Italy. Born in Venice, he absorbed the influences of the Vivarini, the Bellini, and Andrea Mantegna to create an elegant, profuse, effusive, and extreme style, dominated by strong outlines and clear, crisp colors—perhaps incorporating just a whiff of early Netherlandish manuscript style. By 1458 he had left Venice to work in the Marches (the fertile plains south of the Appenines) in and around the port city of Ancona on the Adriatic. As a seaside painter, he could be credited with inventing a second Adriatic style that stands in stark contrast to the soft, suffused colors and gentle contours of Giovanni Bellini.

The subject matter

This Annunciation is signed and dated 1486, so it was an early commission in his adopted territory. The narrative is deceptively simple; the angel Gabriel interrupts the Virgin, engaged in reading and prayer, to announce that she will become the mother of the son of God. The actual event, the incarnation, occurs through words rather than actions, and to be recognizable as a dramatic encounter there are a variety of poses that the Virgin assumes to signify her reaction, from humble acceptance to visible consternation. Crivelli’s version rather peculiarly places Gabriel outside the Virgin’s home, accompanied, in another unusual variation on the theme, by St. Emidius.

Emidius is the patron saint of the town of Ascoli Piceno, and Crivelli painted this altarpiece for the city’s church of the Santissima Annunciazione (the Holy Annunciation). A proud citizen, Emidius seems to have hurried to catch up to Gabriel to proudly show off his detailed model of the town, which he holds rather gingerly, as though the paint hasn’t quite dried.

The fact that Gabriel and the Virgin do not share the same space is unusual, but doesn’t seem to disrupt the delivery of the message. We see the descent of the Holy Spirit has penetrated the frieze of the building, through a conveniently placed arched aperture, into the room where Mary kneels receptively. The inclusion of Emidius brings the miracle of the incarnation home, and this corner of the city is depicted in the kind of deep perspective of contiguous spaces that one sees later in Dutch Baroque domestic scenes, such as Pieter de Hooch’s At the Linen Closet.

The variety of figures in the background on the left of the painting lend an atmosphere of spontaneity and the hubbub of everyday life; at the top of the staircase a little girl peeks around a column, a group of clerics are engaged in conversation and, in the upper mid-ground, two figures stand on the footbridge above the arch, one reading a just-delivered message (echoing the Annunciation).

The inscription along the base of the painting reads “Libertas Ecclesiastica” (church liberty), and refers to Ascoli’s right to self-government, free from the interference of the Pope, a right granted to the town by Sixtus IV in 1482. The news reached Ascoli on 25 March, the Feast of the Annunciation, which is probably the message the official in black is reading.

To the right of the two figures on the bridge, the bases of a crate and a potted plant extend out over the wall just far enough to suggest they could, with a little nudge, topple onto the head of a figure below who, oblivious, shades his eyes to better see the penetrating irradiation of the Holy Spirit entering the wall. He is the witness inside the painting, we are the witnesses outside the painting.

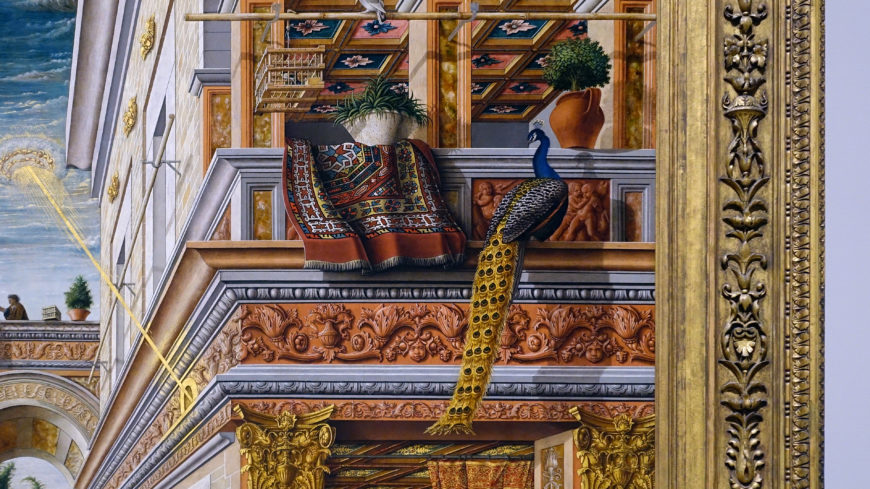

The spatial composition of the overall painting is actually quite traditional, hearkening back to the Annunciation fresco of Piero della Francesca at the church of San Francesco in Arezzo; in both the surface of the painting is essentially vertically bisected by the architecture, while the right half is squared by the horizontal division between the lower room and upper balconies of the Virgin’s dwelling. What is spectacularly different here is Crivelli’s architectural articulation, which consists of an entire dictionary of all’antica elements, made more dramatic by the profusion of materials from which the buildings are made.

The white columns carry gilded capitals, the entablature is elaborated by a red marble frieze, both are illusionistically “carved” with running reliefs of floral, vegetal, and acanthus decoration, springing from beautiful vases, and the frieze is further punctuated with putto heads, lending a sense of animation to the scene. Adding to the ornamentation are egg-and-dart and curious floral dentils, varied marbles, a carved imperial profile relief encircled by a wreath, and crenellations along the farthest wall.

Luxurious costumes

All the major characters wear luxurious costumes, painted to resemble gold and silver embroidered brocades. Gabriel wears a large gold medallion, on a heavy chain, studded with cabochon jewels. Emidius wears a bishop’s mitre similarly jeweled, with a large jeweled clasp on his golden cope. The Virgin wears a jeweled head-band and a dress modestly trimmed with pearls along the top of the bodice. Gabriel’s feathered epaulettes echo his glorious wings, which deserve an essay of their own. The elegant delicacy of Crivelli’s linear style can be seen best in the elongated, pale hands of the Virgin, floating at the ends of her arms, lightly folded across her breast in supplication.

A splendid interior

Rather than occupying a sparsely furnished monastic cell, the Virgin is depicted in a splendidly arrayed interior that echoes the magnificence of the palace exterior. Red and green pillows and blankets embroidered with gold thread cover her bed, with its sweep of red silk curtain, similarly embroidered in gold.

The objects on the shelf above the bed are made of a variety of materials, from the gold candle holder to the barely fluted glass carafe which holds clear water, a sign of Mary’s purity. The grain of the wood in the prie-dieu runs vertically, in contrast to the horizontal grain of the base of the bed, which helps to create the shallow recession in which the Virgin kneels on a splendid carpet.

A sense of cosmopolitanism

At the level of the balcony, Crivelli draws our eye to another carpet, this one displayed draped over the balustrade, and yet another is draped above the arch in the background. Carpets such as these were a major Italian import from the eastern Mediterranean, and used here they lend a cosmopolitan air to the city. The presence of a splendidly feathered peacock, another exotic import, reminds us that carpets from the eastern Mediterranean were coveted luxury items brought in through trade, and they lend an air of cosmopolitanism to the overall scene.

A pickle and an apple?

Of course, the objects that attract the most attention in this painting are the cucumber and apple, placed right in the center foreground of the painting, above the inscription. The cucumber, in fact, seems to project out of the painting and teeter into our space, breaking the fictive wall and blurring the line between a space of miracles and our everyday world. The apple can be taken to symbolize original sin, the source of our fall, the forbidden bite setting into motion the whole reason for the Annunciation. In all fairness, the National Gallery calls the cucumber a gourd (which does sound more Biblical), since cucumbers are part of the gourd family, and leaves it at that, there being neither a Holy Cucumber nor a Holy Gourd. Alas, here we enter the realm of speculation. One school of thought, absent any evidence, is that apples symbolize female sin and cucumbers symbolize male sin. I’ll leave it to you to work out why. Could it be a marrow? Marrows do appear in the Bible, as in Psalm 63:5: “My soul shall be satisfied as with marrow and fatness; and my mouth shall praise thee with joyful lips.” That seems rather appropriate. The controversy rages on.

Additional resources:

This painting at The National Gallery

Stephen John Campbell, C. Jean Campbell, Francesco De Carolis, Ornament and Illusion: Carlo Crivelli of Venice (Paul Holberton Publishing, 2015)

Ronald Lightbown, Carlo Crivelli (Yale University Press; 1st Edition edition, 2004)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

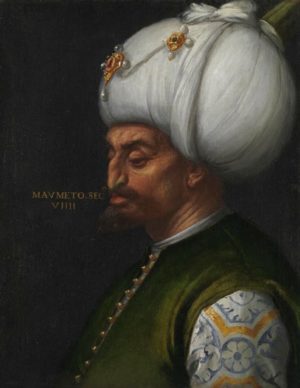

Gentile Bellini, Portrait of Sultan Mehmed II

The afterlife of a painting

In a portrait attributed to the Italian artist Gentile Bellini, we see Sultan Mehmed II surrounded by a classicizing arcade, with a luxurious embroidered tapestry draped over the ledge in front of him. Gentile, already an accomplished portraitist from Venice, painted the sultan’s likeness when he spent 15 months in Constantinople at the court of the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II around 1480 on behalf of the Venetian Republic.

Today this famous portrait belongs to the National Gallery of Art, London. It has had many “afterlives,” that is, many ways it has been re-interpreted and understood since it was produced nearly 550 years ago.

For example, in June of 2020, the Municipality of Istanbul spent over a million dollars at auction for a double portrait featuring the face of Sultan Mehmed II and a young man. The painting is mysterious: it is uncertain who painted it, when, or where, and the identity of the second figure is unknown. The image of the sultan, however, is based on Bellini’s well-known London picture, and the reputation of the mystery painting—as well as Istanbul’s risky purchase—depends on its fame. This is just the most recent, and ongoing, of the London portrait’s “afterlives,” which are the subject of this essay. Before exploring them, however, we must begin with the original painting and its production.

A Venetian travels to paint Sultan Mehmed II

When the London portrait was created, Mehmed was sultan of the Ottoman empire, and ruled from Constantinople (now Istanbul), the city that had been the capital of the Byzantine empire until Mehmed conquered it in 1453. (The Ottomans were Muslim, the Byzantines were Orthodox Christians, and European rulers were faithful to the Church in Rome, or to what we now call Catholicism—and these divergent creeds were no small matter.) Even today, Mehmed is known in Turkish as “Fatih,” or “conqueror.” In addition to being a warrior and politician, he was a great patron, bringing artists and architects together to write, paint, and build. When he petitioned the Venetians to send him artists skilled in portraiture, they sent Gentile Bellini, who seems to have had rare access to the private spaces of Mehmed’s palace. The London portrait is believed to have been produced there, and was probably transported to Italy soon after Mehmed’s death in 1481—by whom is unclear.

The painting resembles many other European portraits of the day, and is dramatically different from contemporary Ottoman portraiture. A single figure, bust-length and life-sized, poses in elaborate dress that reveals his rank and wealth. He is not quite in profile but turned ever so slightly forward, a visual strategy that, along with the carved stone arcade, gives a sense of depth and creates the illusion that the sultan actually sits before us. That illusion is disrupted by the flat, black background and six crowns that seem to float behind him, symbols either of his territorial rule or his place in the chronology of Ottoman sultans. Gentile signed the architectural plinth with his name and date, as a kind of painterly proof of his status as an eyewitness to the sultan (who was often hidden from view) and of the truthfulness of this image.

Why would Mehmed commission such a picture? The answer likely lies in his general curiosity as a patron. We know he studied classical languages, was fascinated by maps, and followed the latest advancements in military architecture. He collected coins and medals, and was aware of their power to glorify a ruler through the circulation of his image. In addition, Mehmed’s interest in portraiture suggests he was up-to-date on some of the most revolutionary things that were happening in Italian painting—in particular, new attempts to depict the world as if it were seen through a window, to paraphrase the contemporary art theorist Leon Battista Alberti. Commissioning a skilled Venetian artist to paint a life-sized, illusionistic portrait might have been a test of just what, exactly, this new form of image making could do.