7.4: Italy in the 15th century- Early Renaissance (I)

- Page ID

- 67070

Italy: 15th century

The Italian city-states were filled with art—all powered by thriving merchant economies.

1400 - 1500 (Early Renaissance)

Beginner’s guide: Italy in the 15th century

This period is often called the Early Renaissance.

1400 - 1500

Carefully observing the natural world, relying on scientific and mathematical tools, and imitating aspects of ancient Greek and Roman art are the cornerstones of the Italian Renaissance.

How to recognize Italian Renaissance art

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): A brief introduction to Italian Renaissance art

Illustrating a Fifteenth-Century Italian Altarpiece

by THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The study of anatomy

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Picking up from the ancients

We can see from Donatello’s sculpture of David—with its careful depiction of bones and muscles and a nude figure—that the study of human anatomy was enormously important for Renaissance artists. They continued where the ancient Greeks and Romans had left off, with an interest in creating images of the human beings where bodies moved in natural ways—in correct proportion and feeling the pull of gravity.

Sculptures from ancient Greece and Rome reveal that classical artists closely observed the human body. Ancient Greek and Roman artists focused their attention on youthful bodies in the prime of life. Ancient sources indicate these artists used models to help them study the details of the body in the way that it looked and moved. These artists tried to show their viewers that they understood systems of muscles beneath the skin.

In the Middle Ages, there was very little interest in the human body, which was seen as only a temporary vessel for the soul. The body was seen as sinful, the cause of temptation. In the Old Testament, Adam and Eve eat the apple from the tree of knowledge, realize their nakedness, and cover themselves. Due to the nudity in this important story, Christians associated nudity with sin and the fall of humankind. Medieval images of naked bodies do not reflect close observation from real life or an understanding of the inner workings of bodies.

Dissection

The best way to learn human anatomy is not just to look at the outside of the body, but to study anatomy through dissection. Even though the Catholic Church prohibited dissection, artists and scientists performed dissection to better understand the body. Renaissance artists were anxious to gain specialized knowledge of the inner workings of the human body, which would allow them to paint and sculpt the body in many different positions.

The artists of the Early Renaissance used scientific tools (like linear perspective and the study of anatomy and geometry) to make their art more naturalistic, more like real life. The term “naturalism” describes this effort.

Scientific naturalism allowed artists in the Early Renaissance to begin to demand that society think of them as more than just skilled manual laborers. They argued that their work—which was based on science and math—was a product of their intellect just as much as their hands. They wanted artists to have the same status as intellectuals and philosophers, unlike the medieval craftsmen that came before them.

Contrapposto explained

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): A discussion about contrapposto while looking at “Idolino” from Pesaro, (Roman), c. 30 B.C.E., bronze, 158 cm (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze), speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Although these particular objects may not have been known in the Renaissance, the ideas and form of contrapposto were revived in the Italian Renaissance.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Florence in the Early Renaissance

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

The Renaissance really gets going in the early years of the fifteenth century in Florence. In this period, which we call the Early Renaissance, Florence is not a city in the unified country of Italy, as it is now. Instead, Italy was divided into many city-states (Florence, Milan, Venice etc.), each with its own government (some were ruled by despots, and others were republics).

The Florentine Republic

We normally think of a Republic as a government where everyone votes for representatives who will represent their interests to the government (think of the United States pledge of allegiance: “and to the republic for which it stands…”). However, Florence was a Republic in the sense that there was a constitution which limited the power of the nobility (as well as laborers) and ensured that no one person or group could have complete political control (so it was far from our ideal of everyone voting, in fact a very small percentage of the population had the vote). Political power resided in the hands of middle-class merchants, a few wealthy families (such as the Medici, important art patrons who would later rule Florence) and the powerful guilds.

Why did the Renaissance begin in Florence?

There are several answers to that question: Extraordinary wealth accumulated in Florence during this period among a growing middle and upper class of merchants and bankers. With the accumulation of wealth often comes a desire to use it to enjoy the pleasures of life—and not an exclusive focus on the hereafter.

Florence saw itself as the ideal city state, a place where the freedom of the individual was guaranteed, and where many citizens had the right to participate in the government (this must have been very different than living in the Duchy of Milan, for example, which was ruled by a succession of Dukes with absolute power). In 1400 Florence was engaged in a struggle with the Duke of Milan. The Florentine people feared the loss of liberty and respect for individuals that was the pride of their Republic.

Luckily for Florence, the Duke of Milan caught the plague and died in 1402. Then, between 1408 and 1414 Florence was threatened once again, this time by the King of Naples, who also died before he could successfully conquer Florence. And in 1423 the Florentine people prepared for war against the son of the Duke of Milan who had threatened them earlier. Again, luckily for Florence, the Duke was defeated in 1425. The Florentine citizens interpreted these military “victories” as signs of God’s favor and protection. They imagined themselves as the “New Rome” — in other words, as the heirs to the Ancient Roman Republic, prepared to sacrifice for the cause of freedom and liberty.

The Florentine people were very proud of their form of government in the early fifteenth century. A republic is, after all, a place that respects the opinions of individuals, individualism was a critical part of the Humanism that thrived in Florence in the fifteenth century.

Additional resources:

Tour: The Early Renaissance in Florence (from the National Gallery of Art)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

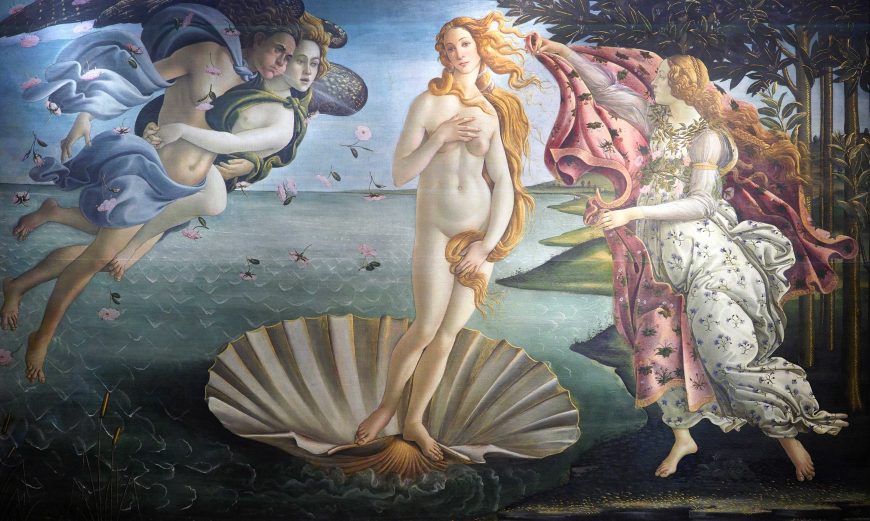

Alberti’s revolution in painting

by DR. LAUREN KILROY-EWBANK and DR. HEATHER GRAHAM

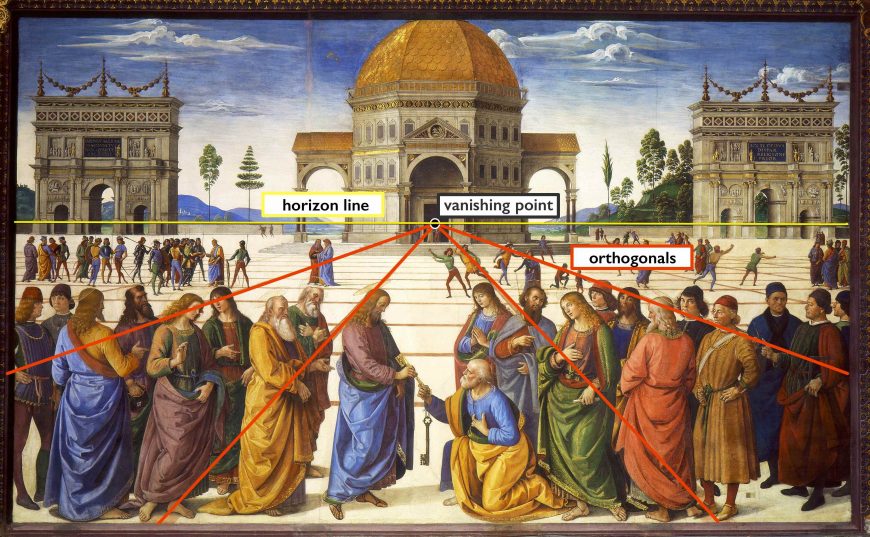

In a fresco high on one wall of the Sistine Chapel, the aged Saint Peter kneels as he humbly accepts the keys of heaven from Jesus Christ standing before him. These two central figures are joined in the immediate foreground by a group of men to either side, some dressed in ancient styles, others in cutting-edge fifteenth-century fashion. They all have volumetric bodies that suggest gentle movement and expressions of solemn concentration. A wide piazza opens behind them, with figures and the piazza’s paving stones receding in scale to suggest a deep space. Forms on the distant horizon fade into an atmospheric haze. A massive building and two triumphal arches, set at even intervals in the background, convey a sense of balance and geometric solidarity.

Pietro Perugino’s biblical scene displays many of the key elements identified as necessary for a successful painting by Leon Battista Alberti in his treatise about painting, including:

- Convincing three-dimensional space

- Light and shadow to create bodies that look three-dimensional

- Figures in varied poses to create a compelling narrative

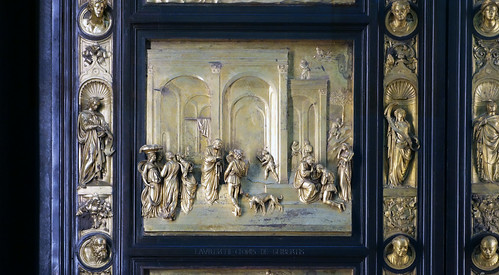

Alberti’s De Pictura (On Painting, 1435) is the first theoretical text written about art in Europe. Originally written in Latin, but published a year later in the Italian vernacular as Della Pittura (1436), this was the first artistic treatise to describe linear perspective and is the first known text in Europe to discuss the purpose of painting. Filippo Brunelleschi’s experiments in linear perspective had occurred earlier in the 1420s, but Alberti codified these ideas in writing. It was during his time living in Florence that Alberti developed his thoughts on painting as he interacted with artists such as Brunelleschi, Donatello, Lorenzo Ghiberti, Masaccio, and others.

These artists experimented with linear perspective before Alberti wrote his text, as we see in Masaccio’s frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel or Donatello’s bronze The Feast of Herod. Alberti encountered first-hand works like Masaccio’s fresco cycle on the life of Saint Peter where biblical characters are convincingly three-dimensional, walk upon solid ground casting shadows, and interact emotionally to tell a story. He dedicated the Italian version of On Painting to the artists from whom he had learned his practical ideas. Alberti’s treatise was more ambitious than simply telling painters how to construct convincing three-dimensional space though. For him, painting “contains a divine force which not only makes absent men present . . . but moreover makes the dead seem almost alive.” [1]

Creating three-dimensional space

Know that a painted thing can never appear truthful where there is not a definite distance for seeing it.

Alberti, On Painting, book 1:46

Alberti believed that good and praiseworthy paintings need to have convincing three-dimensional space, such as we see in Perugino’s fresco. In the first section of On Painting, he explains how to construct logical, rational space based on mathematical principles. It is here that he writes about linear perspective and how to construct a geometrically calculated vanishing point around which a painting’s composition is centered.

A painting attributed to Luciano Laurana of an ideal city envisions Alberti’s ideas. The painting shows a perfectly symmetrical and mathematically defined cityscape. All of the forms within the painting appear to recede away from the viewer and converge at a single point at the center of the horizon line. By having a single vanishing point, Alberti was instructing viewers to look at a painting like The Ideal City as if it were viewed through a window frame.

Making figures look real

There are some who use much gold in their istoria. They think it gives majesty. I do not praise it. Even though one should paint Virgil’s Dido whose quiver was of gold, her golden hair knotted with gold, and her purple robe girdled with pure gold, the reins of the horse and everything of gold, I should not wish gold to be used, for there is more admiration and praise for the painter who imitates the rays of gold with colors.

Alberti, On Painting, book 2:83

For Alberti, the ultimate artistic goal of painting was to rival Nature in the depiction of visual reality. Forms within a painting should be modeled with light and shade to appear sculptural, as though they stand out from the two-dimensional surface like the forms in ancient relief sculpture. Domenico Ghirlandaio’s fresco depicting the birth of the Virgin Mary includes precisely the kind of convincing naturalism Alberti desired. In the scene, women cast shadows, and the deep folds and pleats in their dresses give the impression that their bodies take up space in the two-dimensional fresco.

Alberti also wanted human bodies to appear anatomically correct, and the movements and facial expressions of figures to suggest their emotions. The second part of Alberti’s treatise lays out these ideals, advising painters on how to most effectively tell a story (what he calls an istoria, or narrative) in their art using variety in figure types and gestures. Alberti wanted viewers to be able to relate to the stories portrayed in art and to empathize with painted characters, but he also wanted paintings to present an idealized vision of human behavior. In Ghirlandaio’s scene, women stand, kneel, or sit. Two women in the background lean toward one another to embrace. We also see how Ghirlandaio paints women looking in different directions to create a sense that they are interacting with one another, offering viewers a more compelling narrative than simply showing Saint Anne reclining in bed.

Painting as a liberal art

For their own enjoyment artists should associate with poets and orators who have many embellishments in common with painters and who have a broad knowledge of many things whose greatest praise consists in the invention.

Alberti, On Painting, book 3:89

Why would Alberti go to such great lengths to talk about painting and its purpose? He wished for painting to be viewed as a liberal art, one similar to mathematics or music, rather than as manual labor. His goal was to elevate the status of painting, and painters along with it. One of the ways that he tried to prove that painting was an intellectual endeavor was to look to sources from antiquity. [2] He draws on the ideas of Roman authors such as Pliny the Elder, Quintillian, Cicero, Plutarch, and Lucian, turning to them for their discussions of ancient forms of painting and the artists who made them. He cites Pliny when talking about how artists like Praxiteles or Phidias were so skilled at painting that any work made by the Greek artists was valued more than costly materials like gold and silver. This inclusion and assumed familiarity with classical authors demonstrated his humanist learning and helped to initiate the formal transformation of the visual arts from manual skill to intellectual endeavor.

De Pictura encapsulates many of Alberti’s life pursuits. During his lifetime, he was a humanist, the author of an important architectural treatise, and a literary author who wrote plays, philosophical dialogues, and poetry in addition to working as a practicing architect and artist.

The reception of Alberti’s ideas

Despite the fame of Alberti’s ideas on painting today, this was not the case in his lifetime. Initially, On Painting was not printed—the European printing press wasn’t invented until around 1450. This means that Alberti’s ideas did not have a wide reception until later. Furthermore, renaissance artists would not have been able to read the 1435 Latin version of On Painting. Latin was the language of the educated elite, the language of the class of people who patronized art, not those who made it. It is likely that his initial intent was to share his ideas with a privileged audience, a reminder to us that artists worked at the pleasure of their wealthy employers. When he translated the text, he made it accessible to the people who might actually use his ideas directly.

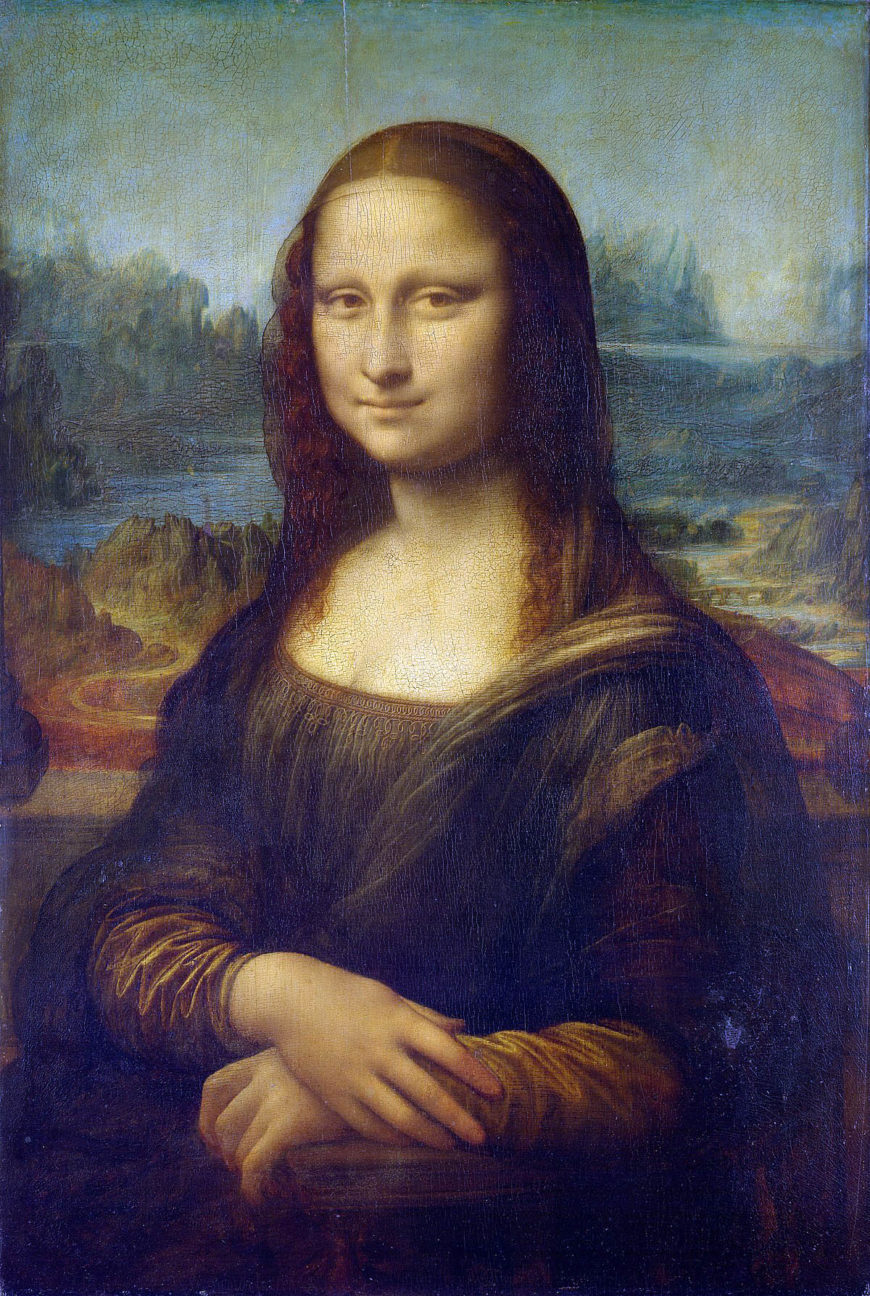

Alberti’s ideas about painting influenced later generations of artists, including the giants of high renaissance art, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. Even those who disagreed with Alberti’s ideas such as northern renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer, proceeded to write down their own ideas about perspective and painting.

Alberti’s ideas would go on to have lasting influence on the history of art. Works of art by many early twentieth-century modern painters, such as Pablo Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon, purposefully reject the illusion of deep space. They were avant-garde precisely because they challenged traditions of painting set in place since the time of Alberti. A painting like René Magritte’s The Human Condition also playfully engages with Alberti’s notion of a painting as a window through which a viewer perceives the world.

Notes:

[1] Alberti, trans. John R. Spencer, rev. ed. (1966), II:62

[2] While the Italian version differs in some respects from the Latin text, the translated work retains the classical references found throughout the Latin version.

Additional resources

Learn more about Alberti as an architect

Virtually explore the Papal Palace and the Sistine Chapel with Smarthistory as your guide

Check out Alberti’s On Painting

Linear Perspective: Brunelleschi’s Experiment

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): An introduction to Filippo Brunelleschi’s experiment regarding linear perspective, c. 1420, in front of the Baptistry in Florence

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

How one-point linear perspective works

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Early applications of linear perspective

Representing the body

What Renaissance artists had clearly achieved through the careful observation of nature, including studies of anatomical dissections, was the means to recreate the three-dimensional physical reality of the human form on two-dimensional surfaces. In part, the key to this achievement lay in understanding the underlying, hidden structure of the human body, which enabled artists to reproduce what it was they saw in the real world on the flat surface of a wall (in the case of frescoes), or that of a wooden panel or paper (in the case of drawings and paintings).

Artists in the early fifteenth century had learned to portray the human form with faithful accuracy through careful observation and anatomical dissection. In 1420, Brunelleschi’s experiment with perspective provided a correspondingly accurate representation of physical space.

Representing space

Antonio Manetti, Brunelleschi’s biographer, writing a century later, describes the experiment based on careful mathematical calculation. It seems reasonable to assume that Brunelleschi devised the method of perspective for architectural purposes—he is said by Manetti to have made a ground plan for the Church of Santo Spirito in Florence (1434-82) on the basis of which he produced a perspective drawing to show his clients how the church would look once built. We can compare this drawing (left) with a modern photo of the actual church (below). It is clear how effective the new technique of mathematical perspective was in depicting spatial reality.

The body in space

But this was just the beginning. Ten years later, the painter Masaccio applied the new method of mathematical perspective even more spectacularly in his fresco The Holy Trinity. The barrel-vaulted ceiling is incredible in its complex, mathematical use of perspective. In this diagram, lines overlay Masaccio’s actual geometric framework to make clear the structure of the perspective system itself.

From the geometry it is actually possible to work backwards to accurately measure and reconstruct the full three-dimensional space that Masaccio depicts—illustrating Brunelleschi’s interest in being able to translate schemata directly between two- and three-dimensional spaces.

It was not long before a decisive step was taken by Leon Battista Alberti, who published a treatise on perspective, Della Pitture (or On Painting), in 1435. Once Alberti’s treatise was published, knowledge of perspective no longer had to be passed on by word of mouth. Newly codified, perspective became not just a matter of artistic interest but a philosophical concern as well.

Additional resources:

The arrow in the eye: The Psychology of Perspective and Renaissance art

Central Italy

A new realism appears in the art of central Italy in the 15th century.

1400 - 1500 (Early Renaissance)

Painting

Gentile da Fabriano

Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi

by DR. JOANNA MILK MAC FARLAND

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi, 1423, tempera on panel, 283 x 300 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

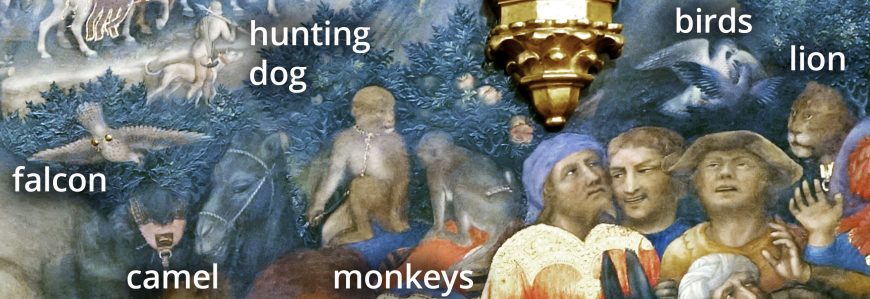

When looking at Gentile da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi, imagine yourself in front of it. Not standing in front of the painting in the bright Uffizi gallery, but in front of an altar in a dark sacristy, watching flickering candlelight dance on layers of silver, gold and paint that have been molded, incised, and glazed into glittering textures. The effect would be overwhelming. Only after this visual shock would you begin to look more closely, wondering what the painting is actually about, who could have painted such a thing, and—perhaps just as importantly for the Renaissance viewer—who could have possibly afforded it. The answers to these questions are complex and intertwined. Yet, with a little historical context, they can be found in the painting itself.

An altarpiece fit for kings

The altarpiece depicts several Gospel stories surrounding the birth of Christ as they were retold in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In the main panel, three Magi (wise men and kings believed to come from unknown, eastern lands) offer gifts to the newly born Christ child. Their adventure begins in the background: smaller scenes of the Magi fill an extraordinary landscape in the three arches above, allowing us to follow their journey in a cartoon-like, continuous narrative.

At far left, they climb a mountain in search of the star they believed would fulfill an ancient prophecy telling of a great king. Following this star, the magi lead their impressive retinue to Jerusalem, shown at the top center of the painting (see image above), and then to the smaller town of Bethlehem at the upper right corner.

The main action of the panel then unfolds in the foreground, where the Magi finally arrive at the small cave where Joseph and Mary have been forced to take shelter with their newborn child. Haloed and resplendent, each king takes his turn offering a gift of gold, frankincense, or myrrh, removing his crown, and kissing the foot of the tiny baby.

As in earlier images of the Magi, they are accompanied by large numbers of courtiers and attendants on horseback as if they were emissaries from a foreign country. More than previous artists, Gentile used the journey of the Magi as an opportunity to flaunt his visual imagination and technical skill. The ‘kings’ do not wear ancient clothing, as one might expect from a biblical story, but imaginative costumes designed to look luxurious and vaguely exotic. The royal retinue is bursting with varied figure types, intricately patterned brocades, and rare animals. Foreground figures are almost stacked on top of one another, as if the ground is tilted forward in order to fill a limited space with a maximum number of figures. Such decorative opulence is continued in the ornate, three-arched frame.

The altarpiece is not just visually busy, but also rich with narrative detail. The dog in the right foreground looks up in fear toward a horse that is about to carelessly step on him. At far left, two female attendants curiously (and somewhat rudely) inspect the precious gift the elderly king has already presented to the holy family.

Even the background includes stories-within-stories. Look for a lonely traveler being accosted by thieves, or for a leopard preparing to pounce toward a local deer he has just spotted from his seat on the back of a horse. These anecdotal, even humorous incidents invite the viewer to inspect each area of the painting carefully, discovering something new at each turn.

From Fabriano to Florence

This was the sort of visual abundance at which Gentile da Fabriano excelled. The artist’s impressive skills were nurtured during his travels to artistic centers throughout Italy. As his name suggests, Gentile was from the town of Fabriano, over a hundred miles southeast of Florence. Years spent in the northern towns of Venice and Brescia in particular encouraged his love of courtly ornamentation and an interest in the close observation of plants and animals. These sojourns also helped build his reputation, and his arrival in Florence by 1422 at the height of his powers would have caused quite the tizzy among the city’s artists and the elite families who patronized them.

At the time, Florence was awash with creativity—a crucible of varying artistic styles. In the works of Lorenzo Monaco, the most successful Florentine painter in these years, an infusion of curving, northern European forms enlivened the inherited tradition of the previous century.

New directions were being pioneered in the practice of sculpture and architecture: Brunelleschi had just conducted his now famous experiment in perspective and the sculptor Donatello helped to revive a taste for classicizing figures and illusionistic depictions of space. The young Masaccio was a scant few years away from changing the history of art by exploring these innovations through the medium of painting.

Palla Strozzi

Into this moment of visual experimentation and change stepped Gentile da Fabriano, a virtual artistic celebrity throughout Italy and beyond. He soon received a prime opportunity to demonstrate his abilities to the city: a prestigious commission from Florence’s wealthiest citizen, Palla Strozzi. Strozzi spent an unprecedented sum on the building and decoration of his family’s chapel in the sacristy of the church of Santa Trinità. Sometime before 1423, the banker turned to Gentile for an altarpiece as part of this project. The Adoration of the Magi represents the result of this commission, showing us that Gentile knew just how to dazzle an expectant audience.

Although we are not sure why a scene of the Adoration was chosen for the painting, it seems likely that Palla saw the subject as an opportunity to display his status in other ways.

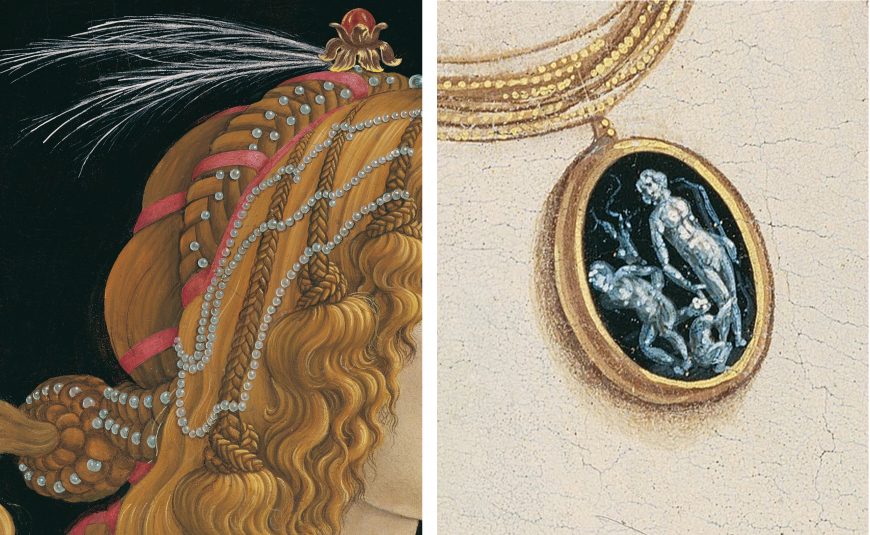

The courtly retinue of Gentile’s painting reminded viewers of Palla’s diplomatic credentials: the banker had travelled as a member of official Florentine visits to various cities throughout Italy. He even had himself depicted as one the Magi’s courtiers. Just behind the third king, he stands holding a falcon—a reference to his family, since strozzieri was the Tuscan word for “falconer” (left).

Other personalized symbols are cleverly included in the painting. The bridle on the white horse to the far right, for example, is decorated with a crescent moon, the central feature on the Strozzi coat-of-arms.

A different kind of naturalism

Gentile’s altarpiece visually announced the amount of gold his patron could purchase and the caliber of artist he could afford to hire. But it also displayed Palla’s cultivated taste for the new and daring. For all of its apparent preoccupation with wealth and worldly status, the Adoration celebrated nature in a way that few paintings had before. People, animals and their movements are carefully observed. Flowers seem to burst forth from the pillars that bracket the frame (see detail above). The subtle modeling of figures’ faces is quite different from the stark contours seen in paintings by popular Florentine artists such as Lorenzo Monaco. And Florentine viewers would surely have noted how fur and fabric were depicted using softer brush strokes than those they were used to seeing. More remarkably, the scenes within this complex structure create a sort of visual dissertation on different kinds of light and shadow. In the main scene, the famous star of Bethlehem illuminates surrounding trees, gilding the edges of their leaves and casting intricate shadows behind the heads of the maids at left.

The small panels below the main scene (a supporting structure known as a predella) are even more experimental in their depiction of different kinds of lighting. The Nativity (image below) is imagined as a night scene with multiple sources of light: the supernatural radiance emanating from the small Christ Child, the brightness of the angel appearing to shepherds in the background, and the much softer glow of the moon at top left.

In the middle predella panel, the new family flees to Egypt against a landscape bathed in the blazing midday sun – a raised golden orb amid a blue sky showering the nearest hillsides in gold. The last panel shows Christ’s presentation in the temple, the building’s dark interior warmly lit by a wall lamp at its center.

Gentile used real gold to achieve many of these subtle lighting effects, demonstrating his ability to combine intricate manipulation of precious materials with an interest in naturalism. Perfecting a technique that would be copied by many other artists, he layered gold leaf underneath layers of paint to lend brightly lit surfaces an added glow—an effect that would be more readily apparent in candlelight. This means precious metals are woven underneath the surface, on the surface, and protruding from the surface, like a tapestry made of paint and gold.

Looking again

To the modern viewer, Gentile’s Adoration may seem too busy, too ornate and too crowded. Even art historians have sometimes had difficulties looking past its emphasis on patterning and flattened space to see how this painting and other works by Gentile contributed to the flowering of the arts in Early Renaissance Florence. Yet the altarpiece’s very richness helped to insure its influence, allowing artists to draw different lessons from Gentile’s painting techniques and visual interests. These contemporary viewers likely understood what present-day visitors to the Uffizi might forget: that the Adoration was not designed to be taken in at a single glance. If we remember this and try to look at the image the way it was meant to be looked at—again and again—it will reward each viewing.

Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi (reframed)

After Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea, during the time of King Herod, Magi from the east came to Jerusalem 2 and asked, “Where is the one who has been born king of the Jews? We saw his star when it rose and have come to worship him.” […] 10 When they saw the star, they were overjoyed. 11 On coming to the house, they saw the child with his mother Mary, and they bowed down and worshiped him. Then they opened their treasures and presented him with gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh.

Matthew 2:1-2, 10-11, NIV

The journey of the wise men

Brilliant golden brocades. Psuedo-Arabic. Turbans. Leopards and lions. Gentile da Fabriano’s Adoration of the Magi creates a dynamic visual narrative of the journey of the Magi to Bethlehem recounted in the Gospel of Matthew. The painting uses continuous narrative to show us the moment the Magi first see the star announcing Jesus’ birth, their journey to Jerusalem, and then subsequent arrival in Bethlehem where they meet the infant Jesus. Three golden arches (forming part of the elaborate frame) differentiate the three narrative moments, although the final moment—when they arrive at the cave in Bethlehem where Mary, Joseph, and Jesus rest—spills across the foreground.

Here the Magi take turns kneeling before Jesus and presenting him with gifts (of gold, frankincense, and myrrh). In Gentile’s painting, the oldest Magi (eventually known as Melchior) is kissing Jesus’ foot, as the Christian messiah (Jesus) touches his head. The other two Magi (Caspar, middle aged; and Balthazar, young) prepare to do the same, holding their gifts aloft. All three Magi are elaborately dressed, and each one has a golden crown.

The Magi were thought to be from east of Europe (though the specific origins of each Magi are not noted in the Bible). By the later Middle Ages, the Magi were understood as standing in for the world, with each of them coming from Asia, Africa, and even Europe. By the fifteenth century, when Gentile was working, this image of a more globalized array of Magi had been widely adopted. It provided a lavish sense of different places, and allowed artists to show a variety of exotic luxury goods. It also helped to give the impression of a united world under God.

Commissioned by Palla Strozzi, a wealthy banker and merchant, for his family’s chapel for the Florentine church of Santa Trinità, the Adoration of the Magi speaks to the global flow of goods at this time, visual transculturation, as well as the European conceptualization of non-European places and peoples.

Psuedo-Arabic

The haloes around the Madonna and Joseph are a brilliant gold, emphasizing their holiness. If we look closely at them, we notice the haloes also include what appears to be writing. This script is actually psuedo-Arabic—a script that approximates Arabic writing, but is not entirely correct. It suggests that the artist could not actually read Arabic; that said, he does include Arabic words as well. The haloes also include decorative rosettes separating each word. Psuedo-Arabic script doesn’t only appear on Mary’s and Joseph’s haloes either. The young page, standing next to the white horse in the foreground, wears a sash written in the script. One of the female figures behind Mary, whose back is turned to us, wears a white shawl decorated with pseudo-Arabic writing. The sleeves of the youngest Magi suggest the script as well, written at the elbow. Here Gentile seems to write the word al-‘ādilī (The Just).[1]

But why would the artist include psuedo-Arabic in one of the holiest scenes from the life of Jesus? One possible reason is that other Italian artists similarly included psuedo-Arabic into their paintings—often on haloes or textiles—and Gentile was continuing this tradition. We find examples in the paintings of Duccio, Giotto, and Masaccio, and in sculptures like Verocchio’s David and Filarete’s doors for the Vatican. Gentile incorporated pseudo-Arabic into other paintings, such as his Madonna of the Humility (c. 1420) and Coronation of the Virgin (c.1420). It is likely more complicated than Gentile solely copying other artists however.

It seems that artists like Gentile borrowed motifs and stylistic patterns from Ayyubid or Mamluk metalwork and textiles that they encountered first hand. These were highly coveted luxury objects and materials, and wealthy families—like the Strozzi—often owned examples. The city of Florence also had made several diplomatic missions to important Muslim trade areas, including one in 1421 to Tunis and another in 1422–23 to Cairo. They established a commercial treaty with the Mamluk sultan in Egypt, and opened a direct trade route to Alexandria via Pisa (which Florence captured in 1406) and Livorno (controlled by Florence after 1421). It has been suggested that these commercial ties may have stimulated even greater interest in luxury objects, like Mamluk brass objects, and the decorative schema found on them.

A third possible reason is that pseudo-Arabic connoted sacredness in some way. The city of Jerusalem (and the Holy Lands more generally) is in the eastern Mediterranean and in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries these areas were controlled by Muslim rulers. Perhaps the use of Arabic script was a way for artists like Giotto and Gentile da Fabriano to reference the Holy Lands within their paintings, or even to suggest the common heritage of Islam and Christianity.

Wearing signs of “the east”

Besides the use of psuedo-Arabic, other elements of the painting point to Gentile’s desire to call to mind “the east” and the exotic sense of the Holy Lands. Multiple figures in the painting wear turbans, a common visual sign that indicated someone from outside Christian Europe, typically someone of Middle Eastern descent. Caspar, the second Magi, wears one. They are used here to suggest the Holy Lands once again, as well as the eastern or non-European origins of some of the Magi. After all, the journey of the Magi takes them to Jerusalem and onto Bethlehem, and so the turban here communicates that the scene is outside of Christian territory, in a more exotic location.

Besides turbans, we also find figures, such as the Magi, wearing elaborate brocades, damasks, other silks, and velvets. Melchior wears a patterned garment of pearlescent white with golden accents, and above that a mantle of burnt siena accented with gold and silver. On both, rosettes and other floral designs animate the surface. Caspar wears a long tunic in black decorated with golden pomegranates.

While the pomegranate was a prominent Christian symbol of rebirth, it was also common as a symbol of its eastern origins and it was a popular motif in Muslim textiles as well. Gentile also includes pomegranate trees in the painting to connote Jerusalem’s and Bethlehem’s eastern locales. Balthazar’s outfit is similarly elaborate. His abdomen is covered in golden designs that almost mimic peacock feathers. His long and elaborate sleeves extend to his knees, and are enlivened by reddish flowers scrolling across the surface. Golden and silver fringe can be found on the edges of his entire outfit.

The exact origins of these textiles is difficult to pinpoint but they all evoke “eastern” patterns and textiles. They could have been acquired by trade from Muslim merchants, or produced in Italy. Cities like Venice, Genoa, and Florence became skilled centers of silk production, and their designs often mimic Muslim textile patterns. Such clothing (whether acquired from afar or made in Italy), was expensive, and was highly sought after by elites. The ornate appearance of the Magi’s clothes in Gentile’s painting does seem to suggest that they are men “from the east.”

An exotic menagerie

As if the painting wasn’t already a feast for the eyes, Gentile has also included a number of non-European or exotic animals into the riotous scene. Two monkeys sit atop a camel. We also find a lion eyeing two birds, and further below a leopard (or possible cheetah) amidst the tightly packed group of men. Animals from outside Europe (Asia, Africa, and eventually the Americas after 1492) were a constant source of interest for Europeans. They were collected, given as gifts, and sometimes even trained to join in courtly hunting expeditions.

Falcons were not necessarily an exotic predatory bird, but falconry had been heavily influenced by Arabian/Muslim traditions. Falcons were especially associated with Persian culture. New falcons acquired from distant lands also appealed to Italian elites. The man holding the falcon is possible a member of the Strozzi family (possibly Palla, the patron) because the Italian word for falconer is strozziere.

Wealthy individuals sometimes acquired exotic animals as a sign of their wealth and their interest in the natural world. Monkeys and apes were popular collectibles, and here they wear collars so as not to escape. Large cats, like the leopard and lion, were sometimes kept and trained for hunting, especially among the northern Italian courts. Exotic animals like camels were popular gifts.

The non-European animals in the painting also help to set the scene in a more exoticized eastern location. The horses are likely Arabian horses, acquired from Muslim trading partners. The camel’s associations with the Holy Lands are mentioned in the Bible. While there is no peacock displayed in the painting, one man does wear a hat/headdress made of its feathers. The peacock, as a symbol of resurrection, dated back to antiquity. Peafowl came from Asia, namely India, and the man’s headgear helps to further associate his eastern origins.

And of course, some of these exotic animals had symbolic meaning that played a role in the painting. Matthew 19:24 famously notes that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven. Here, it might symbolically remind wealthy viewers, like the Strozzi, of this warning.

Material brilliance

The two most expensive materials used in this painting are lapis lazuli and gold. The Virgin Mary’s robe is ultramarine, or a brilliant blue color derived from lapis lazuli. It came from mines in Afghanistan. It could only be mined five months out of the year too, increasing its monetary worth. At this time in the Renaissance, it was more valuable than gold. This is why artists like Gentile often reserved it for Mary’s mantle, using other blue pigments throughout the remainder of the painting.

Gold was also expensive, and Gentile has used a lot of it here. Palla Strozzi, wanting to advertise his wealth, would surely have been thrilled by the lavish use of the gold across the surface. Most gold came from west Africa, traded along caravan routes. Mali, which at one point had been ruled by the powerful and wealthy Musa Keita I (known as Mansa Musa in Europe) reputedly had an enormous amount of gold. When Musa Keita I traveled to Mecca on the hajj between 1324 and 1325 he flooded the market with gold and caused an economic collapse because the price of gold fell steeply.

Gentile doesn’t just incorporate gold into his painting, he uses a technique to suggest an even greater abundance of the precious metal. He uses pastiglia, or raised gilt ornament, which we see on the crowns, swords, spurs, and even on some textiles. It gives these golden areas a three-dimensional quality because they are raised from the flat surface of the painting. Imagine the shimmering quality of all this gold and other material magnificence in the flickering candlelight of the Strozzi chapel!

[1] Ennio G. Napolitano, Arabic Inscriptions and Pseudo-Inscriptions in Italian Art (PhD dissertation, Otto-Friedrich-Universität, Bamberg), p. 99.

Additional resources

Anna Contadini, “Sharing a Taste? Material Culture and Intellectual Curiosity around the Mediterranean, from the Eleventh to the Sixteenth Century,” in The Renaissance and Ottoman World, ed. Anna Contadini and Claire Norton (London: Ashgate, 2013), 24–61.

Rosamund E. Mack, Bazaar to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian art, 1300–1600 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002).

Alexander Nagel, “Twenty-five notes on pseudoscript in Italian art,” RES: Journal of Anthropology and Aesthetics, vol. 59/60 (Spring/Autumn 2011), pp. 229–248.

Patricia Lee Rubin, Images and Identity in Fifteenth-century Florence (New Haven and London:Yale University Press, 2007).

Masaccio

Masaccio, Virgin and Child Enthroned

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Masaccio (Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Simone), Virgin and Child Enthroned, 1426, tempera on panel (National Gallery, London)

Ser Giuliano degli Scarsi, a notary from Pisa, commissioned this altarpiece for the chapel of Saint Julian in Santa Maria del Carmine, Pisa.

Masaccio, Holy Trinity

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427, fresco, 667 x 317 cm, Santa Maria Novella, Florence

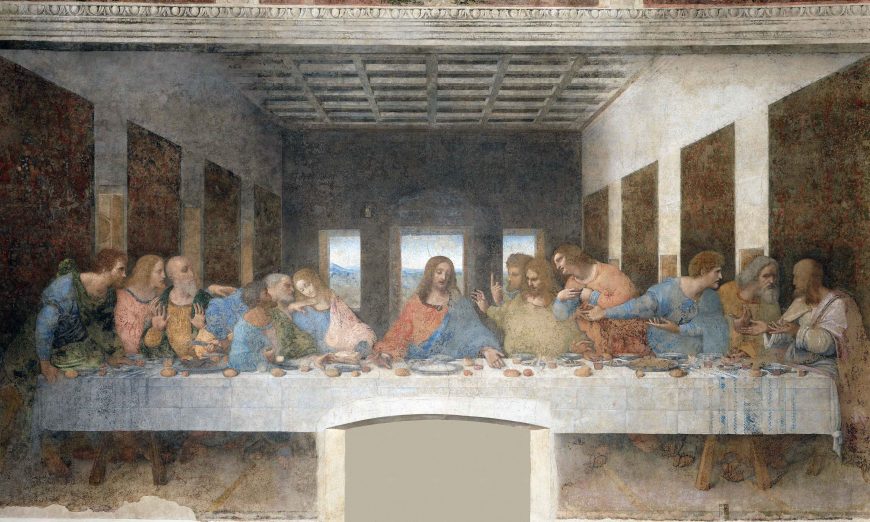

Masaccio was the first painter in the Renaissance to incorporate Brunelleschi’s discovery, linear perspective, in his art. He did this in his fresco the Holy Trinity, in Santa Maria Novella, in Florence.

Have a close look at the painting and at this perspective diagram. The orthogonals can be seen in the edges of the coffers in the ceiling (look for diagonal lines that appear to recede into the distance). Because Masaccio painted from a low viewpoint, as though we were looking up at Christ, we see the orthogonals in the ceiling, and if we traced all of the orthogonals, we would see that the vanishing point is on the ledge that the donors kneel on.

God’s feet

Our favorite part of this fresco is God’s feet. Actually, you can only really see one of them.

God is standing in this painting. This may not strike you all that much when you first think about it because our idea of God, our picture of God in our minds eye—as an old man with a beard—is very much based on Renaissance images of God. So, here Masaccio imagines God as a man. Not a force or a power, or something abstract, but as a man. A man who stands—his feet are foreshortened, and he weighs something and is capable of walking. In medieval art, God was often represented by a hand, as though God was an abstract force or power in our lives—but here he seems so much like a flesh and blood man. This is a good indication of Humanism in the Renaissance.

Masaccio’s contemporaries were struck by the palpable realism of this fresco, as was Vasari who lived over one hundred years later. Vasari wrote that “the most beautiful thing, apart from the figures, is a barrel-shaped vaulting, drawn in perspective and divided into squares filled with rosettes, which are foreshortened and made to diminish so well that the wall appears to be pierced.”¹

The architecture

One of the other remarkable things about this fresco is the use of the forms of classical architecture (from ancient Greece and Rome). Masaccio borrowed much of what we see from ancient Roman architecture, and may have been helped by the great Renaissance architect Brunelleschi.

Coffers – the indented squares on the ceiling

Column – a round, supporting element in architecture. In this fresco by Masaccio we see an attached column

Pilasters – a shallow, flattened out column attached to a wall—it is only decorative, and has no supporting function

Barrel Vault – vault means ceiling, and a barrel vault is a ceiling in the shape of a round arch

Ionic and Corinthian Capitals – a capital is the decorated top of a column or pilaster. An ionic capital has a scroll shape (like the ones on the attached columns in the painting), and a Corinthian capital has leaf shapes.

Fluting – the vertical, indented lines or grooves that decorated the pilasters in the painting—fluting can also be applied to a column

1. Vasari, “Masaccio” in Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects the Artists (first published in 1550 in Italian)

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\)

Additional resources:

Masaccio, The Tribute Money in the Brancacci Chapel

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Masaccio, The Tribute Money, 1427, fresco (Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence)

The Tribute Money is one of many frescoes painted by Masaccio (and another artist named Masolino) in the Brancacci chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence—when you walk into the chapel, the fresco is on your upper left. All of the frescoes in the chapel tell the story of the life of St. Peter. The story of the Tribute Money is told in three separate scenes within the same fresco. This way of telling an entire story in one painting is called a continuous narrative.

A story unfolds and a miracle is performed

In the Tribute Money, a Roman tax collector (the figure in the foreground in a short orange tunic and no halo) demands tax money from Christ and the twelve apostles who don’t have the money to pay.

Christ (in the center, wearing a pinkish robe gathered in at the waist, with a blue toga-like wrap) points to the left, and says to Peter “so that we may not offend them, go to the lake and throw out your line. Take the first fish you catch; open its mouth and you will find a four-drachma coin. Take it and give it to them for my tax and yours” (Matthew 17:27). Christ performed a miracle—and the apostles have the money to pay the tax collector. In the center of the fresco (scene 1), we see the tax collector demanding the money, and Christ instructing Peter. On the far left (scene 2), we see Peter kneeling down and retrieving the money from the mouth of a fish, and on the far right (scene 3), St. Peter pays the tax collector. In the fresco, the tax collector appears twice, and St. Peter appears three times (you can find them easily if you look for their clothing).

We are so used to one moment appearing in one frame (think of a comic book, for example) that the unfolding of the story within one image (and out of order!) seems very strange to us. But with this technique (a continuous narrative)—which was also used by the ancient Romans—Masaccio is able to make an entire drama unfold on the wall of the Brancacci chapel.

In the central, first scene, the tax collector points down with his right hand, and holds his left palm open, impatiently insisting on the money from Christ and the apostles. He stands with his back to us, which helps to create an illusion of three dimensional space in the image (a goal which was clearly important to Masaccio as he also employed both linear and atmospheric perspective to create an illusion of space). Like Donatello’s St. Mark from Orsanmichele in Florence, he stands naturally, in contrapposto, with his weight on his left leg, and his right knee bent. The apostles (Christ’s followers) look worried and anxiously watch to see what will happen. St. Peter (wearing a large deep orange colored toga draped over a blue shirt) is confused, as he seems to be questioning Christ and pointing over to the river, but he also looks like he is willing to believe Christ.

The gestures and expressions help to tell the story. Peter seems confused and points to the lake—mirroring Christ’s gesture; the tax collector looks upset, and has his hand out insistently asking for the money—he stands in contrapposto with his back turned to us (contrapposto is a standing position, where the figure’s weight is shifted to one leg). Only Christ is completely calm because he is performing a miracle.

Look down at the feet—how the light travels through the figures, and is stopped when it encounters the figures. The figures cast shadows—Masaccio is perhaps the first artist since classical antiquity to paint cast shadows. What this does is make the fresco so much more real—it is as if the figures are truly standing out in a landscape, with the light coming from one direction, and the sun in the sky, hitting all the figures from the same side and casting shadows on the ground. For the first time since antiquity, there is almost a sense of weather.

Additional resources:

Masaccio, the Old Master who died young (The Guardian)

The Magic of Illusion: Masaccio’s Holy Trinity, from the National Gallery of Art

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Masaccio, Holy Trinity

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427, fresco, 667 x 317 cm, Santa Maria Novella, Florence

Masaccio was the first painter in the Renaissance to incorporate Brunelleschi’s discovery, linear perspective, in his art. He did this in his fresco the Holy Trinity, in Santa Maria Novella, in Florence.

Have a close look at the painting and at this perspective diagram. The orthogonals can be seen in the edges of the coffers in the ceiling (look for diagonal lines that appear to recede into the distance). Because Masaccio painted from a low viewpoint, as though we were looking up at Christ, we see the orthogonals in the ceiling, and if we traced all of the orthogonals, we would see that the vanishing point is on the ledge that the donors kneel on.

God’s feet

Our favorite part of this fresco is God’s feet. Actually, you can only really see one of them.

God is standing in this painting. This may not strike you all that much when you first think about it because our idea of God, our picture of God in our minds eye—as an old man with a beard—is very much based on Renaissance images of God. So, here Masaccio imagines God as a man. Not a force or a power, or something abstract, but as a man. A man who stands—his feet are foreshortened, and he weighs something and is capable of walking. In medieval art, God was often represented by a hand, as though God was an abstract force or power in our lives—but here he seems so much like a flesh and blood man. This is a good indication of Humanism in the Renaissance.

Masaccio’s contemporaries were struck by the palpable realism of this fresco, as was Vasari who lived over one hundred years later. Vasari wrote that “the most beautiful thing, apart from the figures, is a barrel-shaped vaulting, drawn in perspective and divided into squares filled with rosettes, which are foreshortened and made to diminish so well that the wall appears to be pierced.”¹

The architecture

One of the other remarkable things about this fresco is the use of the forms of classical architecture (from ancient Greece and Rome). Masaccio borrowed much of what we see from ancient Roman architecture, and may have been helped by the great Renaissance architect Brunelleschi.

Coffers – the indented squares on the ceiling

Column – a round, supporting element in architecture. In this fresco by Masaccio we see an attached column

Pilasters – a shallow, flattened out column attached to a wall—it is only decorative, and has no supporting function

Barrel Vault – vault means ceiling, and a barrel vault is a ceiling in the shape of a round arch

Ionic and Corinthian Capitals – a capital is the decorated top of a column or pilaster. An ionic capital has a scroll shape (like the ones on the attached columns in the painting), and a Corinthian capital has leaf shapes.

Fluting – the vertical, indented lines or grooves that decorated the pilasters in the painting—fluting can also be applied to a column

1. Vasari, “Masaccio” in Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects the Artists (first published in 1550 in Italian)

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\)

Additional resources:

Masaccio, The Tribute Money in the Brancacci Chapel

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Masaccio, The Tribute Money, 1427, fresco (Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence)

The Tribute Money is one of many frescoes painted by Masaccio (and another artist named Masolino) in the Brancacci chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence—when you walk into the chapel, the fresco is on your upper left. All of the frescoes in the chapel tell the story of the life of St. Peter. The story of the Tribute Money is told in three separate scenes within the same fresco. This way of telling an entire story in one painting is called a continuous narrative.

A story unfolds and a miracle is performed

In the Tribute Money, a Roman tax collector (the figure in the foreground in a short orange tunic and no halo) demands tax money from Christ and the twelve apostles who don’t have the money to pay.

Christ (in the center, wearing a pinkish robe gathered in at the waist, with a blue toga-like wrap) points to the left, and says to Peter “so that we may not offend them, go to the lake and throw out your line. Take the first fish you catch; open its mouth and you will find a four-drachma coin. Take it and give it to them for my tax and yours” (Matthew 17:27). Christ performed a miracle—and the apostles have the money to pay the tax collector. In the center of the fresco (scene 1), we see the tax collector demanding the money, and Christ instructing Peter. On the far left (scene 2), we see Peter kneeling down and retrieving the money from the mouth of a fish, and on the far right (scene 3), St. Peter pays the tax collector. In the fresco, the tax collector appears twice, and St. Peter appears three times (you can find them easily if you look for their clothing).

We are so used to one moment appearing in one frame (think of a comic book, for example) that the unfolding of the story within one image (and out of order!) seems very strange to us. But with this technique (a continuous narrative)—which was also used by the ancient Romans—Masaccio is able to make an entire drama unfold on the wall of the Brancacci chapel.

In the central, first scene, the tax collector points down with his right hand, and holds his left palm open, impatiently insisting on the money from Christ and the apostles. He stands with his back to us, which helps to create an illusion of three dimensional space in the image (a goal which was clearly important to Masaccio as he also employed both linear and atmospheric perspective to create an illusion of space). Like Donatello’s St. Mark from Orsanmichele in Florence, he stands naturally, in contrapposto, with his weight on his left leg, and his right knee bent. The apostles (Christ’s followers) look worried and anxiously watch to see what will happen. St. Peter (wearing a large deep orange colored toga draped over a blue shirt) is confused, as he seems to be questioning Christ and pointing over to the river, but he also looks like he is willing to believe Christ.

The gestures and expressions help to tell the story. Peter seems confused and points to the lake—mirroring Christ’s gesture; the tax collector looks upset, and has his hand out insistently asking for the money—he stands in contrapposto with his back turned to us (contrapposto is a standing position, where the figure’s weight is shifted to one leg). Only Christ is completely calm because he is performing a miracle.

Look down at the feet—how the light travels through the figures, and is stopped when it encounters the figures. The figures cast shadows—Masaccio is perhaps the first artist since classical antiquity to paint cast shadows. What this does is make the fresco so much more real—it is as if the figures are truly standing out in a landscape, with the light coming from one direction, and the sun in the sky, hitting all the figures from the same side and casting shadows on the ground. For the first time since antiquity, there is almost a sense of weather.

Additional resources:

Masaccio, the Old Master who died young (The Guardian)

The Magic of Illusion: Masaccio’s Holy Trinity, from the National Gallery of Art

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Masaccio, Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden in the Brancacci Chapel

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): Masaccio, Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Eden, Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, Italy, c. 1424-27, fresco, 7 feet x 2 feet 11 inches

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Fra Angelico

Fra Angelico, The Annunciation and Life of the Virgin (c. 1426)

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{12}\): Fra Angelico, The Annunciation and Life of the Virgin (in the predella), c. 1426, tempera on wood, 194 x 194 cm (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

The Annunciation is described in the Gospel According to Luke 1:26 – 38. Here is the King James translation:

And in the sixth month the angel Gabriel was sent from God unto a city of Galilee, named Nazareth, To a virgin espoused to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David; and the virgin’s name [was] Mary. And the angel came in unto her, and said, Hail, [thou that art] highly favoured, the Lord [is] with thee: blessed [art] thou among women. And when she saw [him], she was troubled at his saying, and cast in her mind what manner of salutation this should be. And the angel said unto her, Fear not, Mary: for thou hast found favour with God. And, behold, thou shalt conceive in thy womb, and bring forth a son, and shalt call his name JESUS. He shall be great, and shall be called the Son of the Highest: and the Lord God shall give unto him the throne of his father David: And he shall reign over the house of Jacob for ever; and of his kingdom there shall be no end. Then said Mary unto the angel, How shall this be, seeing I know not a man? And the angel answered and said unto her, The Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the Highest shall overshadow thee: therefore also that holy thing which shall be born of thee shall be called the Son of God. And, behold, thy cousin Elisabeth, she hath also conceived a son in her old age: and this is the sixth month with her, who was called barren. For with God nothing shall be impossible. And Mary said, Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to thy word. And the angel departed from her.

Fra Angelico, The Annunciation (c. 1438-47)

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{13}\): Fra Angelico, The Annunciation, c. 1438-47, fresco, 230 x 321 cm (Convent of San Marco, Florence)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Paolo Uccello, Battle of San Romano

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{14}\): Paolo Uccello, Battle of San Romano, probably c. 1438-40, (National Gallery, London)

Fra Filippo Lippi

Domenico Veneziano, Saint Lucy Altarpiece

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{15}\): Domenico Veneziano, Saint Lucy Altarpiece, 1445-47, tempera on wood panel, 82 1/4 x 85″ or 209 x 216 cm (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence)

Additional resources

This painting at the Uffizi

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

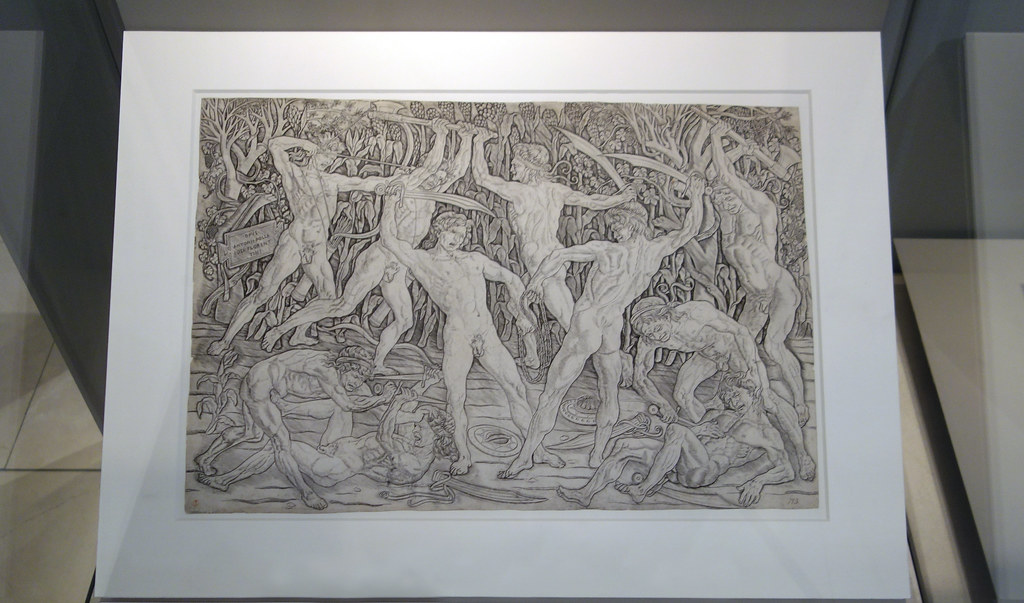

Antonio Pollaiuolo, Battle of Ten Nudes or (Battle of Nude Men)

Antonio Pollaiuolo’s Battle of Ten Nudes has been called the single most important engraving in European history. Clearly based on classical antiquity (the cultures of ancient Greece and Rome), the print is monumental in size (approximately 15 x 23 inches) and, because of its shallow space, resembles ancient Roman relief sculpture. In the picture, five men wearing headbands fight against an equal number of men without headbands. The battle is set in front of a wall of lush vegetation.

Art historians disagree about whether the print depicts a particular scene from mythology or classical history, but some have suggested that it simply shows gladiators. This is because in the central pair, the men are gripping a chain, a common weapon of gladiatorial combat.

The print is exceptional for many reasons. To begin with, over fifty copies of it exist, an extraordinarily high number for a work of art over 500 years old. Additionally, it is believed that Pollaiuolo engraved the print completely by his own hand, and for this reason, the sign set in the far left of the vegetation bears his name (most often the artist’s composition would be engraved by a printmaker).

Pollaiuolo’s print is, however, important mostly because it shows a new conception of the human body. As many art historians have noted, the Renaissance started much earlier in the fields of sculpture and architecture than it did in painting and drawing. So although Donatello had created his nude David decades earlier, the nude had yet to be mastered in a two-dimensional form. Not everyone was taken with Pollaiuolo’s print, and it is believed that Leonardo da Vinci criticized it, saying that the bodies looked like “bags of nuts.” Pollaiuolo’s nudes may be overly muscular, but they were probably the most naturalistic human bodies created in Italy up to that point.

Vasari, the great sixteenth-century Florentine artist and art historian, wrote that Pollaiuolo’s understanding of the nude body resulted from his dissection of cadavers. This became a common practice in Florence, and it is reported that a sculpture of the crucified Christ in Santo Spirito was a gift from a very young Michelangelo to the priest there, who basically let him rob graves for the purpose of dissection.

Pollaiuolo’s bodies are also derivative of ancient Roman art, an indication that he was looking at the classical past for inspiration, an essential hallmark of the Renaissance.

Because Pollaiuolo was trained as a goldsmith (this was true of many artists of the Renaissance including Ghiberti and Brunelleschi), he was very skilled in working with metal. Apart from its conception of the nude, the print also showcases the artist’s technical ability, especially in the modeling, or contouring of light and dark, used to create volume in the men’s bodies.

Although to the modern viewer, the fight between the ten men may look stiff and posed (although, a particularly vivacious passage can be found in the bottom left hand corner, where the man on the ground fiercely strains against the man pressing his head into the ground), later works by Michelangelo and Leonardo owe much to it. It is impossible to think that either Michelangelo’s Battle of the Centaurs (below) and Battle of Cascina or Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari could have existed without the prototype of Pollaiuolo’s Battle of Ten Nudes.

This print is an engraving. That means that with a sharp tool, Pollaiuolo scratched the drawing into a sheet of metal. Ink was then applied to the metal surface and subsequently wiped off, leaving only the incised lines filled in. A piece of moist paper was then set over the plate, which was sent through rollers so that the wet paper could “suck up” the ink. At the end, the sheet of paper was peeled off, and the image that resulted was the mirror image of what Pollaiuolo drew.

In fact, art historians have identified that two stages of the print actually exist. This means that at some point, the metal plate wore down, and the artist had to recarve some of the details back into the plate. The result is that, over time, two different images were pulled from Pollaiuolo’s one plate.

Because prints were collected like modern day baseball cards, engravings of The Battle of Ten Nudes ended up all over Europe, and many other artists copied it. Although people in other parts of Europe might read about the great sculptures and buildings being constructed in Florence, Pollaiuolo’s print was an actual piece of the Florentine Renaissance that they could hold in their hands. Prints like this did much in helping to spread the Renaissance throughout Italy and to the rest of the world.

Additional resources:

This print at the British Museum

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

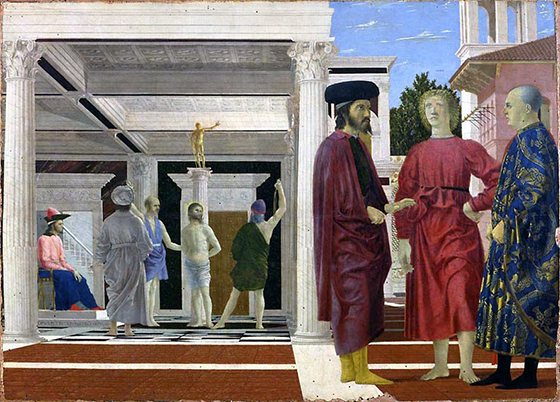

Perugino, Christ Giving the Keys of the Kingdom to St. Peter

by DR. SHANNON PRITCHARD

St. Peter—keeper of the keys

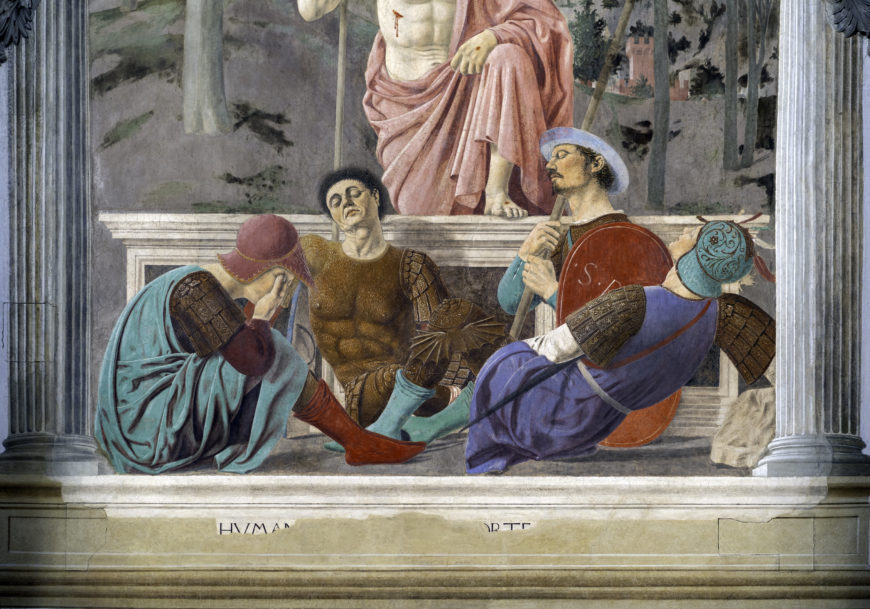

Pietro Perugino’s Christ Giving the Keys of the Kingdom to St. Peter is an exemplar of Italian Renaissance painting. The work was part of a large decorative program commissioned by Pope Sixtus IV in 1481 for the walls of the Sistine Chapel (the name “Sistine” being derived from Sixtus’ own name), which was then, as it is today, the pope’s private chapel in the Vatican, in Rome. This large scale fresco, measuring 10’10” x 18’, is part of the New Testament narrative cycle depicting events from the life of Christ on the north wall of the chapel (the south wall illustrates the Old Testament life of Moses).

The painting shows the moment when Christ, standing in the center dressed purple and blue garments, gives the keys of the heavenly kingdom to the kneeling St. Peter. This episode comes from the Gospel of Matthew (16:18-19) as Christ said to Peter: “And I tell you that you are Peter (Petros), and on this rock (petra) I will build my church… I will give you the keys to the kingdom of heaven….” The pair of gold and silver keys became Saint Peter’s attribute (an attribute, in this sense, is an object associated with a saint that aids the viewer in identifying the saint). More about Peter

The Renaissance ideal

Perugino pulled out every pictorial device in his painter’s arsenal to construct an image that is reflective of Renaissance ideals: figures, balance, harmony, and three-dimensional space. To begin with, see that the pictorial field has been clearly delineated into three distinct planes: foreground, middle-ground and background. In the foreground, on either side of Christ and St. Peter—are the other eleven Apostles. Who are the Apostles?

You can identify them easily since they are the figures dressed in classicizing tunics and robes. Each has been carefully rendered as a distinct individual. Perugino harmonizes the figures through repeating colors and postures. Notice how blue, yellow, and green are repeated throughout the group in a way that draws the viewer’s eye back and forth across the foreground.

Let’s also look at the postures of our Apostles. At the left and right edge of the Apostolic group is a figure with his back to the viewer, looking toward the central action. This effectively draws our eye to the center as well. The next figure over on both sides, faces out towards us, and their poses are mirror reflections of one another. Perugino’s harmoniously balanced grouping of historical figures provides visual interest for the viewer.

However, there is one element that is incongruous with the rest, which is the addition of contemporary Roman and Florentine men at the far edges of the groups on either side of Peter and Christ. These figures are clearly not part of the biblical figures based on their dress— and there is even a portrait of the artist himself, who looks directly out to the viewer on the right hand side (the fifth figure from the right edge—see the image above) ! The inclusion of the artist and / or contemporary people associated with the project was common during the Italian Renaissance, and in this case, Perugino’s presence acts as his visual signature to his work.

In the middle-ground, the figures are much smaller than those in the foreground, suggestive of their spatial distance. Not merely passersby, these figures are part of two additional stories from the life of Christ. On the left is the Tribute Money from the Gospel of Matthew (17:24-27) where the Roman tax collector demands Christ pay the Emperor’s tax. (This scene was famously represented by Masaccio in the Brancacci Chapel in Florence). On the right is the Stoning of Christ from the Gospel of John (8:48-59). The addition of these two scenes creates a pictorial device known as a continuous narrative, where two or more related events are shown occurring simultaneously in one composition.

The background is comprised of three architectural structures at the edge of the open piazza (plaza), with an ideal landscape extending far into the distance behind. In order to create such a believable sense of three-dimensional space, Perugino utilized two types of perspective.

The first, one-point linear perspective, creates a believable three-dimensional space using a system of orthogonals (diagonal lines seen on the pavement—in red in the diagram above) that recede into space, converging at one point known as the “vanishing point” (which in this case is in the doorway of the central building).”

The vanishing point is located along a horizontal line, the “horizon line,” which establishes the boundary between land and sky (the blue line in the diagram above). Notice how all of the figures maintain a proportional relationship to each other as they recede into this space.

The second type of perspective Perugino used is atmospheric perspective, which is literally the effect of the atmosphere on objects observed in the distance, causing them to diminish in appearance through a bluish-gray haze, as seen in the mountains in this case.

The influence of classical antiquity

Contrapposto

One of the defining characteristics of the Italian Renaissance was the interest in all aspects of classical antiquity (ancient Greece and Rome), especially its art and architecture. That interest in manifested in Perugino’s fresco in two different ways. One is his use of contrapposto (Italian meaning “counter-pose”) for some of the foreground figures.

This pose (seen in the figure above) was known in the Renaissance through copies of the ancient Greek sculpture, the Doryphoros (above right). When standing in contrapposto, one leg bears all of the person’s weight while remains relaxed at the knee, producing a very natural stance (notice how often you stand in contrapposto every day!).

Architecture

The second nod to antiquity is in the architecture. The central “temple” in the background of Perugino’s fresco is based on the Florence Baptistery, which was believed at the time to have been an ancient Roman temple.

And at either side of the piazza are representations of the Arch of Constantine (in Rome). The arch commemorates Constantine the Great, the Roman emperor who legalized Christianity in 314. Famously converting to Christianity on his deathbed in 336, he effectively became the first Christian Roman emperor. Moreover, Constantine founded St. Peter’s Basilica, the site of Peter’s burial and the location of Perugino’s fresco. Thus, the inclusion of the Arch of Constantine was an important reference to the history of Rome, and St. Peter and the basilica.

Ghirlandaio, Life of the Virgin

by DR. SALLY HICKSON

A treasure house of Renaissance art

The Church of Santa Maria Novella, adjacent to the train station of the same name, is a treasure-house of Florentine art of the Renaissance.

So much so, that visitors to the church—seeking the great Renaissance artists Uccello and Masaccio and the wondrous frescoes in the “Spanish Chapel”—are sometimes prone to overlook the magnificence of its main altar chapel (or chancel), painted by the absolute master of Florentine fresco, Domenico Ghirlandaio and his workshop. Known as the Tornabuoni chapel (for the family that commissioned the paintings), the frescoes were once the culmination of the pilgrim’s journey down the central nave and through a large wooden choir (an area for seating for the clergy and choir), which funneled the traveler through the final third of the journey to deliver them at the doorstep of Ghirlandaio’s glorious vision (the painter and author Vasari tore the choir down in the sixteenth century—as it turns out, he wasn’t much one for preserving material culture).

A banker’s commission

At the time of this commission, the Tornabuoni were the chief Florentine banking rivals of the Medici. Like the Medici, they employed this kind of sacred patronage to expiate themselves against charges of immoral luxuriousness and wealth, as well as to quell suspicions of usury (charging interest, which was considered a sin). The irony, of course, is that a fresco insurance policy as grand as this one was only obtained at great cost, and was intended to attract maximum public attention. The extravagant “humility” of rich patrons (the Medici, the Tornabuoni and others), adorning the city with thinly-veiled monuments to themselves, came to be considered a demonstration of virtuous public service, celebrated as civic magnificenza. I suppose Donald Drumpf may see himself in the much the same way, scattering his showy, shiny monuments across America.

The Bible in Florence

Ghirlandaio loved Florence and fresco, and he adored the world and all of its charms. In contrast to the solid, stoic and severe formal classicism of the earlier generation of Alberti, Brunelleschi and Masaccio, Ghirlandaio loved form, color, variety, narrative and the quotidian (everyday) details of Florentine daily life. Although the primary narratives depicted in the Tornabuoni Chapel are scenes from the Life of John the Baptist and from the Life of the Virgin, these biblical scenes unfold in the streets of Florence, often staged in what appear to be temporary stage-sets, theatrical triumphal arches and temples, strewn with various bits of ancient Roman bric-a-brac, hastily assembled for the biblical actors. When you peer through the arches of these Lego-land wonders, you see the solid, sturdy, stone medieval façades of Florence—no matter where he goes in his imagination, for Ghirlandaio, Florence is the whole world. The conflation of time past and time present in the frescoes is also underscored by the inclusion, in many scenes, of late-fifteenth-century members of the Tornabuoni family in the biblical subjects, floating across the stage like ghostly apparitions. For over 500 years these vivid frescoes have played across the walls of the chapel like a continuously looping documentary film, chronicling the living history of Florence.

The painter

Domenico Ghirlandaio is often given rather short shrift by art historians existing, as he did, suspended between the austere Albertian mathematical rationalism of the fifteenth century and the agonized, self-flagellant extravagances of Michelangelo, to whom he served as painting master before he took up residence in the Medici garden. Trained in the family workshop, Ghirlandaio was an acknowledged fresco expert, and while his style is sometimes dismissed as “prosaic,” I find it happily idiomatic, clearly reveling in the quotidian joys of observing the world around him—which is not to say that he lacked imagination. He had a distinct penchant for embellishing severe classical architectural settings with fanciful, fluid and flirtatious decorative flourishes and then peopling them with the most extraordinarily vivid and lively figures.

Every picture tells a story: The narratives

The overall narrative program of the chapel is relatively simple, covering the two lateral walls, and part of the rear wall (around and above the magnificent stained-glass windows) in superimposed registers, culminating in frescoes of the Four Evangelists on the ceiling.

Facing into the chapel, the frescoes to the viewer’s left tell the story of the life of the Virgin, to whom the church is dedicated, and those on the right, the story of the Life of St. John the Baptist, the patron saint of Florence. Both of these narratives feature birth scenes; the birth of John the Baptist, the Birth of the Virgin, the Nativity of Christ. The message is clear—three mothers, two sons, two dispensations. John’s fate, as the last Prophet of the Old Testament and first Apostle of the New Testament, is to recognize Jesus as the Messiah—this translation from old to new is the lynchpin that holds the cycles together.

The fact that some of these biblical births are attended by prominent and highly recognizable female members of the Tornabuoni family reveals at least two subtexts behind this natal cycle—in the first instance, it’s about dynasty, continuity, and the perpetuation of the Tornabuoni family. But there is a sad and ironic touch to this dynastic documentary; in the birth scenes of St. John and of the Virgin, a cortege of court ladies is led into the scene by the wife of Lorenzo Tornabuoni, the solemnly beautiful Giovanna who sadly died In childbirth while Ghirlandaio was painting this cycle (a lovely portrait of Giovanna by Ghirlandaio, left). The frescoes are, therefore, touching commemorative tributes to Giovanna, mingling the joys of birth with the sadness of death and the hope for eternal salvation.

The life of the Virgin

Among the many lovely aspects of the life of the Virgin, the loveliest is the story of her conception, born of a kiss between the aged Joachim and the long-barren Saint Ann, as they linger by the city gate. Ghirlandaio places this close encounter of the biblical kind at the top of a staircase inside what appears to be a contemporary Florentine palace, where it gives way seamlessly to the contiguous Birth of the Virgin, easily the best-known scene from the chapel.