2.5: Ancient Greece

- Page ID

- 63720

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Ancient Greece

Ancient Greek art, with its love of the human body, is perhaps the most influential art ever made.

c. 900 - 146 B.C.E.

A beginner’s guide: Ancient Greece

The Greeks were united by a shared language, religion, and culture.

c. 700 - 146 B.C.E.

By around 500 B.C.E. “rule by the people,” or democracy, emerged in the city of Athens. Following the defeat of the Persian Empire, Greece (and Athens in particular) entered a golden age of art, literature, and philosophy.

Ancient Greece, an introduction

The ancient Greeks lived in many lands around the Mediterranean Sea, from Turkey to the south of France. They had close contacts with other peoples such as the Egyptians, Syrians and Persians.The Greeks lived in separate city-states, but shared the same language and religious beliefs.

Bronze Age Greece

During the Bronze Age (around 3200 – 1100 B.C.E.), a number of cultures flourished on the islands of the Cyclades, in Crete and on the Greek mainland. They were mainly farmers, but trade across the sea, particularly in raw materials such as obsidian (volcanic glass) and metals, was growing.

Mycenaean culture flourished on the Greek mainland in the Late Bronze Age, from about 1600 to 1100 B.C.E. The name comes from the site of Mycenae, where the culture was first recognized after the excavations in 1876 of Heinrich Schliemann.

The Mycenaean period of the later Greek Bronze Age was viewed by the Greeks as the “age of heroes” and perhaps provides the historical background to many of the stories told in later Greek mythology, including Homer’s epics. Objects and artworks from this time are found throughout mainland Greece and the Greek islands. Distinctive Mycenaean pottery was distributed widely across the eastern Mediterranean. These show the beginnings of Greek mythology being used to decorate works of art. They come from about the same time that the epics of Homer were reaching the form in which we inherit them, as the earliest Greek literature.

The collapse of Mycenaean civilization around 1100 B.C.E. brought about a period of isolation known as the Dark Age. But by around 800 B.C.E. the revival had begun as trade with the wider world increased, arts, crafts and writing re-emerged and city-states (poleis) developed.

Archaic period

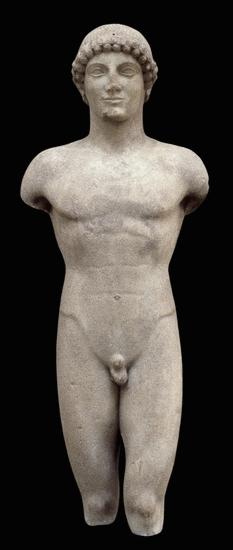

Two of the most distinctive forms of free-standing sculpture to emerge during the Archaic period of Greek art (about 600-480 B.C.E.) were statues of youths (kouroi) and maidens (korai).

Kouros (the singular form) is a term used to describe a type of statue of a male figure produced in marble during the Archaic period of Greek art. Such statues can be colossal (that is larger than life) or less than life size. They all have a conventional pose, where the head and body can be divided equally by a central line, and the legs are parted with the weight placed equally front and back. The male figures, usually in the form of naked young men, acted both as grave markers and as votive offerings, the latter perhaps intended to be representations of the dedicator. The female figures served similar functions, but differed from their male counterparts in that they were elaborately draped.

The mouth is invariably fixed in a smile, which is probably a symbolic expression of the arete (“excellence”) of the person represented. It used to be thought that all kouroi were representations of the god Apollo. However, although some may be representations of gods or heroes, many were simply grave markers. The kouros was not intended as a realistic portrait of the deceased, but an idealized representation of values and virtues to which the dead laid claim: youthful beauty, athleticism, and aristocratic bearing, among others.

Classical period

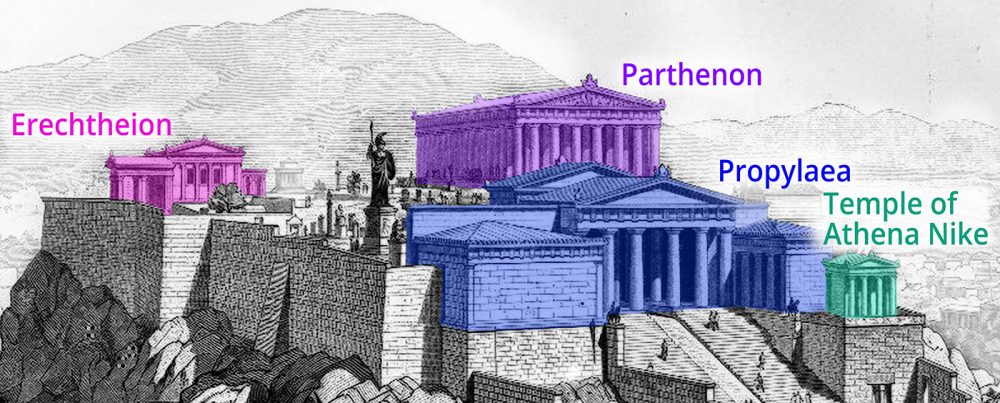

By around 500 B.C.E. “rule by the people,” or democracy, had emerged in the city of Athens. Following the defeat of a Persian invasion in 480-479 B.C.E., mainland Greece and Athens in particular entered into a golden age. In drama and philosophy, literature, art and architecture, Athens was second to none. The city’s empire stretched from the western Mediterranean to the Black Sea, creating enormous wealth. This paid for one of the biggest public building projects ever seen in Greece, which included the Parthenon.

Ancient Greece also played a vital role in the early history of coinage. As well as making some of the world’s earliest coins, the ancient Greeks were the first to use them extensively in trade.

Hellenistic period

Following the death of Alexander and the division of his empire, the Hellenistic period (323-31 B.C.E.) saw Greek power and culture extended across the Middle East and as far as the Indus Valley. When Rome absorbed the Greek world into its vast empire, Greek ideas, art and culture greatly influenced the Romans.

Alexander was always shown clean-shaven, which was an innovation: all previous portraits of Greek statesmen or rulers had beards. This royal fashion lasted for almost five hundred years and almost all of the Hellenistic kings and Roman emperors until Hadrian were portrayed beardless.

The British Museum collection includes objects from across the entire Greek world, ranging in date from the beginning of pre-history to early Christianity in the Byzantine era.

© Trustees of the British Museum

Introduction to ancient Greek art

A shared language, religion, and culture

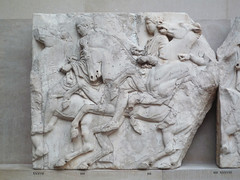

Ancient Greece can feel strangely familiar. From the exploits of Achilles and Odysseus, to the treatises of Aristotle, from the exacting measurements of the Parthenon (image above) to the rhythmic chaos of the Laocoön (image below), ancient Greek culture has shaped our world. Thanks largely to notable archaeological sites, well-known literary sources, and the impact of Hollywood (Clash of the Titans, for example), this civilization is embedded in our collective consciousness—prompting visions of epic battles, erudite philosophers, gleaming white temples, and limbless nudes (we now know the sculptures—even the ones that decorated temples like the Parthenon—were brightly painted, and, of course, the fact that the figures are often missing limbs is the result of the ravages of time).

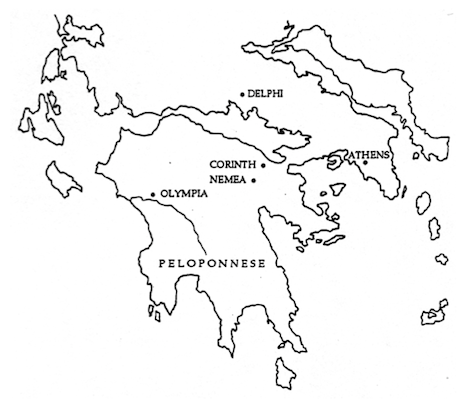

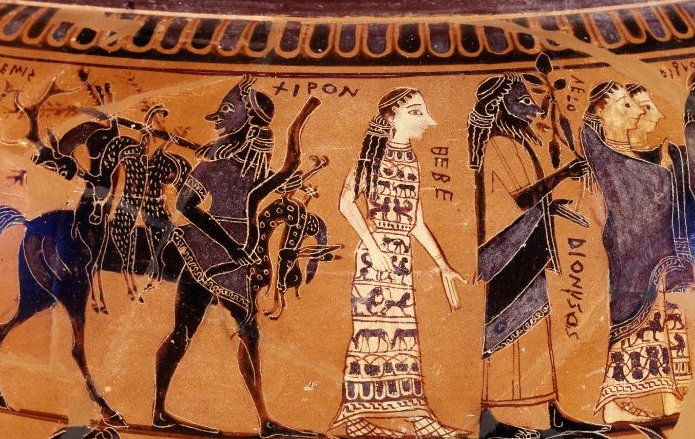

Dispersed around the Mediterranean and divided into self-governing units called poleis or city-states, the ancient Greeks were united by a shared language, religion, and culture. Strengthening these bonds further were the so-called “Panhellenic” sanctuaries and festivals that embraced “all Greeks” and encouraged interaction, competition, and exchange (for example the Olympics, which were held at the Panhellenic sanctuary at Olympia). Although popular modern understanding of the ancient Greek world is based on the classical art of fifth century B.C.E. Athens, it is important to recognize that Greek civilization was vast and did not develop overnight.

The Dark Ages (c. 1100 – c. 800 B.C.E.) to the Orientalizing Period (c. 700 – 600 B.C.E.)

Following the collapse of the Mycenaean citadels of the late Bronze Age, the Greek mainland was traditionally thought to enter a “Dark Age” that lasted from c. 1100 until c. 800 B.C.E. Not only did the complex socio-cultural system of the Mycenaeans disappear, but also its numerous achievements (i.e., metalworking, large-scale construction, writing). The discovery and continuous excavation of a site known as Lefkandi, however, drastically alters this impression. Located just north of Athens, Lefkandi has yielded an immense apsidal structure (almost fifty meters long), a massive network of graves, and two heroic burials replete with gold objects and valuable horse sacrifices. One of the most interesting artifacts, ritually buried in two separate graves, is a centaur figurine (see photos below). At fourteen inches high, the terracotta creature is composed of a equine (horse) torso made on a potter’s wheel and hand-formed human limbs and features. Alluding to mythology and perhaps a particular story, this centaur embodies the cultural richness of this period.

Similar in its adoption of narrative elements is a vase-painting likely from Thebes dating to c. 730 B.C.E. (see image below). Fully ensconced in the Geometric Period (c. 800-700 B.C.E.), the imagery on the vase reflects other eighth-century artifacts, such as the Dipylon Amphora, with its geometric patterning and silhouetted human forms. Though simplistic, the overall scene on this vase seems to record a story. A man and woman stand beside a ship outfitted with tiers of rowers. Grasping at the stern and lifting one leg into the hull, the man turns back towards the female and takes her by the wrist. Is the couple Theseus and Ariadne? Is this an abduction? Perhaps Paris and Helen? Or, is the man bidding farewell to the woman and embarking on a journey as had Odysseus and Penelope? The answer is unattainable.

In the Orientalizing Period (700-600 B.C.E.), alongside Near Eastern motifs and animal processions, craftsmen produced more nuanced figural forms and intelligible illustrations. For example, terracotta painted plaques from the Temple of Apollo at Thermon (c. 625 B.C.E.) are some of the earliest evidence for architectural decoration in Iron Age Greece. Once ornamenting the surface of this Doric temple (most likely as metopes), the extant panels have preserved various imagery (watch this video to learn about the Doric order). On one plaque (see image below), a male youth strides towards the right and carries a significant attribute under his right arm—the severed head of the Gorgon Medusa (her face is visible between the right hand and right hip of the striding figure). Not only is the painter successful here in relaying a particular story, but also the figure of Perseus shows great advancement from the previous century. The limbs are fleshy, the facial features are recognizable, and the hat and winged boots appropriately equip the hero for fast travel.

The Archaic Period (c. 600-480/479 B.C.E.)

While Greek artisans continued to develop their individual crafts, storytelling ability, and more realistic portrayals of human figures throughout the Archaic Period, the city of Athens witnessed the rise and fall of tyrants and the introduction of democracy by the statesman Kleisthenes in the years 508 and 507 B.C.E.

Visually, the period is known for large-scale marble kouros (male youth) and kore (female youth) sculptures (see below). Showing the influence of ancient Egyptian sculpture (like this example of the Pharaoh Menkaure and his wife in the MFA, Boston), the kouros stands rigidly with both arms extended at the side and one leg advanced. Frequently employed as grave markers, these sculptural types displayed unabashed nudity, highlighting their complicated hairstyles and abstracted musculature (below left). The kore, on the other hand, was never nude. Not only was her form draped in layers of fabric, but she was also ornamented with jewelry and adorned with a crown. Though some have been discovered in funerary contexts, like Phrasiklea (below right), a vast majority were found on the Acropolis in Athens (for the Acropolis korai, click here). Ritualistically buried following desecration of this sanctuary by the Persians in 480 and 479 B.C.E., dozens of korai were unearthed alongside other dedicatory artifacts. While the identities of these figures have been hotly debated in recent times, most agree that they were originally intended as votive offerings to the goddess Athena.

The Classical Period (480/479-323 B.C.E.)

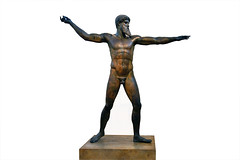

Though experimentation in realistic movement began before the end of the Archaic Period, it was not until the Classical Period that two- and three-dimensional forms achieved proportions and postures that were naturalistic. The “Early Classical Period” (480/479 – 450 B.C.E., also known as the “Severe Style”) was a period of transition when some sculptural work displayed archaizing holdovers. As can be seen in the Kritios Boy, c. 480 B.C.E., the “Severe Style” features realistic anatomy, serious expressions, pouty lips, and thick eyelids. For painters, the development of perspective and multiple ground lines enriched compositions, as can be seen on the Niobid Painter’s vase in the Louvre (image below).

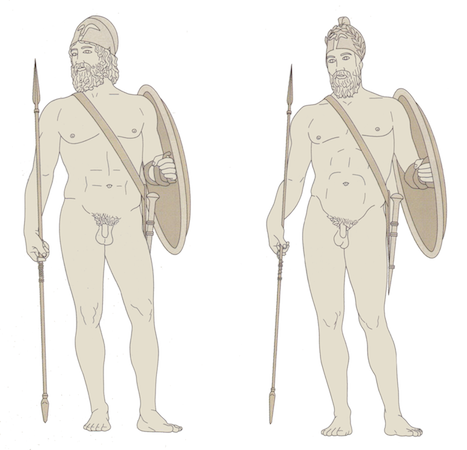

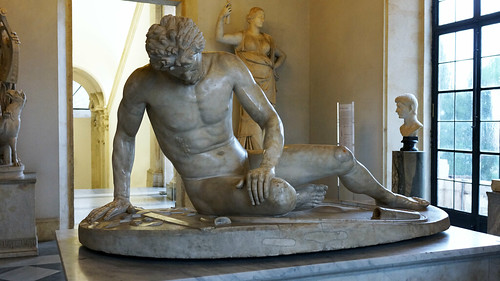

During the “High Classical Period” (450-400 B.C.E.), there was great artistic success: from the innovative structures on the Acropolis to Polykleitos’ visual and cerebral manifestation of idealization in his sculpture of a young man holding a spear, the Doryphoros or “Canon” (image below). Concurrently, however, Athens, Sparta, and their mutual allies were embroiled in the Peloponnesian War, a bitter conflict that lasted for several decades and ended in 404 B.C.E. Despite continued military activity throughout the “Late Classical Period” (400-323 B.C.E.), artistic production and development continued apace. In addition to a new figural aesthetic in the fourth century known for its longer torsos and limbs, and smaller heads (for example, the Apoxyomenos), the first female nude was produced. Known as the Aphrodite of Knidos, c. 350 B.C.E., the sculpture pivots at the shoulders and hips into an S-Curve and stands with her right hand over her genitals in a pudica (or modest Venus) pose (see a Roman copy in the Capitoline Museum in Rome here). Exhibited in a circular temple and visible from all sides, the Aphrodite of Knidos became one of the most celebrated sculptures in all of antiquity.

The Hellenistic Period and Beyond (323 B.C.E. – 31 B.C.E.)

Following the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C.E., the Greeks and their influence stretched as far east as modern India. While some pieces intentionally mimicked the Classical style of the previous period such as Eutychides’ Tyche of Antioche (Louvre), other artists were more interested in capturing motion and emotion. For example, on the Great Altar of Zeus from Pergamon (below) expressions of agony and a confused mass of limbs convey a newfound interest in drama.

Architecturally, the scale of structures vastly increased, as can be seen with the Temple of Apollo at Didyma, and some complexes even terraced their surrounding landscape in order to create spectacular vistas as can be seem at the Sanctuary of Asklepios on Kos. Upon the defeat of Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E., the Ptolemaic dynasty that ruled Egypt and, simultaneously, the Hellenistic Period came to a close. With the Roman admiration of and predilection for Greek art and culture, however, Classical aesthetics and teachings continued to endure from antiquity to the modern era.

Additional resources:

The Art of classical Greece from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Richard T. Neer, Greek Art and Archaeology: A New History, c. 2500-c. 150 B.C.E. (Thames and Hudson, 2011)

Robin Osborne, Archaic and Classical Greek Art (Oxford University Press, 1988)

John G. Pedley, Greek Art and Archaeology (Pearson, 2011)

J.J. Pollitt, Art and Experience in Classical Greece (Cambridge University Press, 1972)

Nigel Jonathan Spivey, Greek Art (Phaeton Press, 1997)

Contrapposto explained

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

The ancient Greeks mastered the naturalistic representation of the human body, and the Renaissance revived it.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): A discussion about contrapposto while looking at “Idolino” from Pesaro, (Roman), c. 30 B.C.E., bronze, 158 cm (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Firenze), speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Although these particular objects may not have been known in the Renaissance, the ideas and form of contrapposto were revived in the Italian Renaissance.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Introduction to ancient Greek architecture

For most of us, architecture is easy to take for granted. It’s everywhere in our daily lives—sometimes elegant, other times shabby, but generally ubiquitous. How often do we stop to examine and contemplate its form and style? Stopping for that contemplation offers not only the opportunity to understand one’s daily surroundings, but also to appreciate the connection that exists between architectural forms in our own time and those from the past. Architectural tradition and design has the ability to link disparate cultures together over time and space—and this is certainly true of the legacy of architectural forms created by the ancient Greeks.

Where and when

Greek architecture refers to the architecture of the Greek-speaking peoples who inhabited the Greek mainland and the Peloponnese, the islands of the Aegean Sea, the Greek colonies in Ionia (coastal Asia Minor), and Magna Graecia (Greek colonies in Italy and Sicily).

Greek architecture stretches from c. 900 B.C.E. to the first century C.E. (with the earliest extant stone architecture dating to the seventh century B.C.E.).

Greek architecture influenced Roman architecture and architects in profound ways, such that Roman Imperial architecture adopts and incorporates many Greek elements into its own practice.

An overview of basic building typologies demonstrates the range and diversity of Greek architecture.

Temple

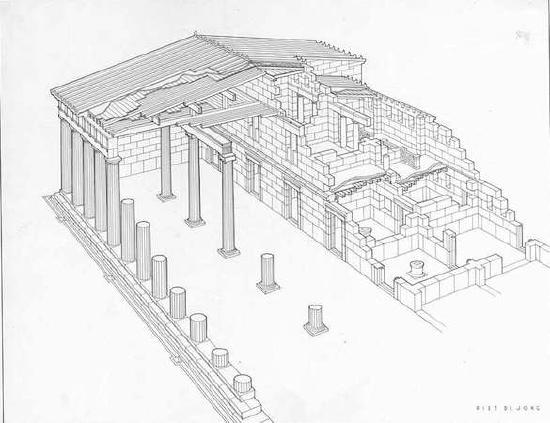

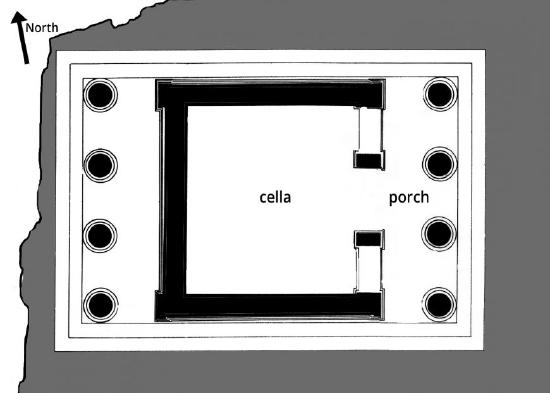

The most recognizably “Greek” structure is the temple (even though the architecture of Greek temples is actually quite diverse). The Greeks referred to temples with the term ὁ ναός (ho naós) meaning “dwelling,” temple derives from the Latin term, templum. The earliest shrines were built to honor divinities and were made from materials such as a wood and mud brick—materials that typically don’t survive very long. The basic form of the naos (the interior room that held the cult statue of the God or Gods) emerges as early as the tenth century B.C.E. as a simple, rectangular room with projecting walls (antae) that created a shallow porch. This basic form remained unchanged in its concept for centuries. In the eighth century B.C.E. Greek architecture begins to make the move from ephemeral materials (wood, mud brick, thatch) to permanent materials (namely, stone).

During the Archaic period the tenets of the Doric order of architecture in the Greek mainland became firmly established, leading to a wave of monumental temple building during the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.E. Greek city-states invested substantial resources in temple building—as they competed with each other not just in strategic and economic terms, but also in their architecture. For example, Athens devoted enormous resources to the construction of the acropolis in the 5th century B.C.E.—in part so that Athenians could be confident that the temples built to honor their gods surpassed anything that their rival states could offer.

The multi-phase architectural development of sanctuaries such as that of Hera on the island of Samos demonstrate not only the change that occurred in construction techniques over time but also how the Greeks re-used sacred spaces—with the later phases built directly atop the preceding ones. Perhaps the fullest, and most famous, expression of Classical Greek temple architecture is the Periclean Parthenon of Athens—a Doric order structure, the Parthenon represents the maturity of the Greek classical form.

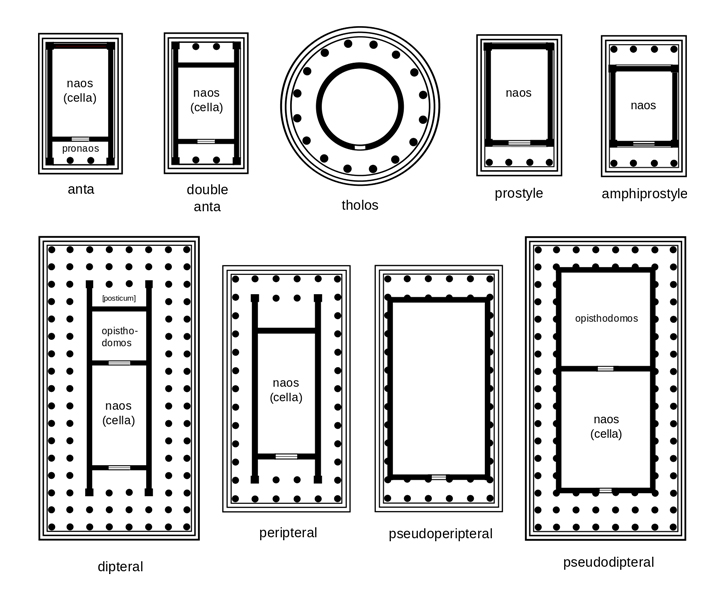

Greek temples are often categorized in terms of their ground plan and the way in which the columns are arranged. A prostyle temple is a temple that has columns only at the front, while an amphiprostyle temple has columns at the front and the rear. Temples with a peripteral arrangement (from the Greek πτερον (pteron) meaning “wing) have a single line of columns arranged all around the exterior of the temple building. Dipteral temples simply have a double row of columns surrounding the building. One of the more unusual plans is the tholos, a temple with a circular ground plan; famous examples are attested at the sanctuary of Apollo in Delphi and the sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidauros.

Stoa

Stoa (στοά) is a Greek architectural term that describes a covered walkway or colonnade that was usually designed for public use. Early examples, often employing the Doric order, were usually composed of a single level, although later examples (Hellenistic and Roman) came to be two-story freestanding structures. These later examples allowed interior space for shops or other rooms and often incorporated the Ionic order for interior colonnades.

Greek city planners came to prefer the stoa as a device for framing the agora (public market place) of a city or town. The South Stoa constructed as part of the sanctuary of Hera on the island of Samos (c. 700-550 B.C.E.) numbers among the earliest examples of the stoa in Greek architecture. Many cities, particularly Athens and Corinth, came to have elaborate and famous stoas. In Athens the famous Stoa Poikile (“Painted Stoa”), c. fifth century B.C.E., housed paintings of famous Greek military exploits including the battle of Marathon, while the Stoa Basileios (“Royal Stoa”), c. fifth century B.C.E., was the seat of a chief civic official (archon basileios).

Later, through the patronage of the kings of Pergamon, the Athenian agora was augmented by the famed Stoa of Attalos (c. 159-138 B.C.E.) which was recently rebuilt according to the ancient specifications and now houses the archaeological museum for the Athenian Agora itself (see image above). At Corinth the stoa persisted as an architectural type well into the Roman period; the South Stoa there (above), c. 150 C.E., shows the continued utility of this building design for framing civic space. From the Hellenistic period onwards the stoa also lent its name to a philosophical school, as Zeno of Citium (c. 334-262 B.C.E.) originally taught his Stoic philosophy in the Stoa Poikile of Athens.

Theater

The Greek theater was a large, open-air structure used for dramatic performance. Theaters often took advantage of hillsides and naturally sloping terrain and, in general, utilized the panoramic landscape as the backdrop to the stage itself. The Greek theater is composed of the seating area (theatron), a circular space for the chorus to perform (orchestra), and the stage (skene). Tiered seats in the theatron provided space for spectators. Two side aisles (parados, pl. paradoi) provided access to the orchestra. The Greek theater inspired the Roman version of the theater directly, although the Romans introduced some modifications to the concept of theater architecture. In many cases the Romans converted pre-existing Greek theaters to conform to their own architectural ideals, as is evident in the Theater of Dionysos on the slopes of the Athenian Acropolis. Since theatrical performances were often linked to sacred festivals, it is not uncommon to find theaters associated directly with sanctuaries.

Bouleuterion

The Bouleuterion (βουλευτήριον) was an important civic building in a Greek city, as it was the meeting place of the boule (citizen council) of the city. These select representatives assembled to handle public affairs and represent the citizenry of the polis (in ancient Athens the boule was comprised of 500 members). The bouleuterion generally was a covered, rectilinear building with stepped seating surrounding a central speaker’s well in which an altar was placed. The city of Priène has a particularly well-preserved example of this civic structure as does the city of Miletus.

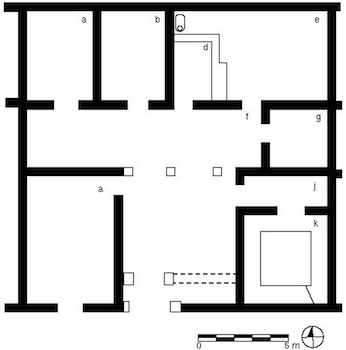

House

Greek houses of the Archaic and Classical periods were relatively simple in design. Houses usually were centered on a courtyard that would have been the scene for various ritual activities; the courtyard also provided natural light for the often small houses. The ground floor rooms would have included kitchen and storage rooms, perhaps an animal pen and a latrine; the chief room was the andron—site of the male-dominated drinking party (symposion). The quarters for women and children (gynaikeion) could be located on the second level (if present) and were, in any case, segregated from the mens’ area. It was not uncommon for houses to be attached to workshops or shops. The houses excavated in the southwest part of the Athenian Agora had walls of mud brick that rested on stone socles and tiled roofs, with floors of beaten clay.

The city of Olynthus in Chalcidice, Greece, destroyed by military action in 348 B.C.E., preserves many well-appointed courtyard houses arranged within the Hippodamian grid-plan of the city. House A vii 4 had a large cobbled courtyard that was used for domestic industry. While some rooms were fairly plain, with earthen floors, the andron was the most well-appointed room of the house.

Fortifications

The Mycenaean fortifications of Bronze Age Greece (c. 1300 B.C.E.) are particularly well known—the megalithic architecture (also referred to as Cyclopean because of the use of enormous stones) represents a trend in Bronze Age architecture. While these massive Bronze Age walls are difficult to best, first millennium B.C.E. Greece also shows evidence for stone built fortification walls. In Attika (the territory of Athens), a series of Classical and Hellenistic walls built in ashlar masonry (squared masonry blocks) have been studied as a potential system of border defenses. At Palairos in Epirus (Greece) the massive fortifications enclose a high citadel that occupies imposing terrain.

Stadium, gymnasium, and palaestra

The Greek stadium (derived from stadion, a Greek measurement equivalent to c. 578 feet or 176 meters) was the location of foot races held as part of sacred games; these structures are often found in the context of sanctuaries, as in the case of the Panhellenic sanctuaries at Olympia and Epidauros. Long and narrow, with a horseshoe shape, the stadium occupied reasonably flat terrain.

The gymnasium (from the Greek term gymnós meaning “naked”) was a training center for athletes who participated in public games. This facility tended to include areas for both training and storage. The palaestra (παλαίστρα) was an exercise facility originally connected with the training of wrestlers. These complexes were generally rectilinear in plan, with a colonnade framing a central, open space.

Altar

Since blood sacrifice was a key component of Greek ritual practice, an altar was essential for these purposes. While altars did not necessarily need to be architecturalized, they could be and, in some cases, they assumed a monumental scale. The third century B.C.E. Altar of Hieron II at Syracuse, Sicily, provides one such example. At c. 196 meters in length and c. 11 m in height the massive altar was reported to be capable of hosting the simultaneous sacrifice of 450 bulls (Diodorus Siculus History 11.72.2).

Another spectacular altar is the Altar of Zeus from Pergamon, built during the first half of the second century B.C.E. The altar itself is screened by a monumental enclosure decorated with sculpture; the monument measures c. 35.64 by 33.4 meters. The altar is best known for its program of relief sculpture that depict a gigantomachy (battle between the Olympian gods and the giants) that is presented as an allegory for the military conquests of the kings of Pergamon. Despite its monumental scale and lavish decoration, the Pergamon altar preserves the basic and necessary features of the Greek altar: it is frontal and approached by stairs and is open to the air—to allow not only for the blood sacrifice itself but also for the burning of the thigh bones and fat as an offering to the gods.

Fountain house

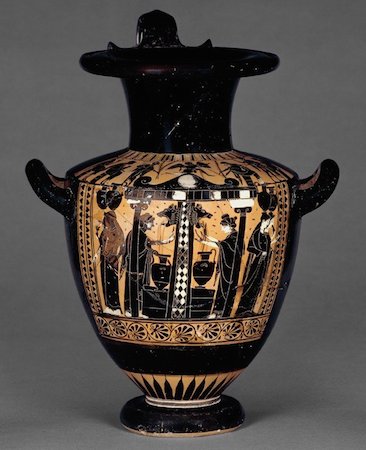

The fountain house is a public building that provides access to clean drinking water and at which water jars and containers could be filled. The Southeast Fountain house in the Athenian Agora (c. 530 B.C.E.) provides an example of this tendency to position fountain houses and their dependable supply of clean drinking water close to civic spaces like the agora. Gathering water was seen as a woman’s task and, as such, it offered the often isolated women a chance to socialize with others while collecting water. Fountain house scenes are common on ceramic water jars (hydriai), as is the case for a Black-figured hydria (c. 525-500 B.C.E.) found in an Etruscan tomb in Vulci that is now in the British Museum

Legacy

The architecture of ancient Greece influenced ancient Roman architecture, and became the architectural vernacular employed in the expansive Hellenistic world created in the wake of the conquests of Alexander the Great. Greek architectural forms became implanted so deeply in the Roman architectural mindset that they endured throughout antiquity, only to then be re-discovered in the Renaissance and especially from the mid-eighteenth century onwards as a feature of the Neo-Classical movement. This durable legacy helps to explain why the ancient Greek architectural orders and the tenets of Greek design are still so prevalent—and visible—in our post-modern world.

Additional resources:

Architecture in Ancient Greece on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

B. A. Ault and L. Nevett, Ancient Greek Houses and Households: Chronological, Regional, and Social Diversity (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005).

N. Cahill, Household and City Organization at Olynthus (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001).

J. J. Coulton, The Architectural Development of the Greek Stoa (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976).

J. J. Coulton, Ancient Greek Architects at Work: Problems of Structure and Design (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1982).

W. B. Dinsmoor, The Architecture of Greece: an Account of its Historic Development 3rd ed. (London: Batsford, 1950).

Marie-Christine Hellmann, L’architecture Grecque 3 vol. (Paris: Picard, 2002-2010).

M. Korres, Stones of the Parthenon (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000).

A. W. Lawrence, Greek Architecture 5th ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996).

C. G. Malacrino, Constructing the Ancient World: Architectural Techniques of the Greeks and Romans (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010).

A. Mazarakis Ainian, From Rulers’ Dwellings to Temples: Architecture, Religion and Society in early Iron Age Greece (1100-700 B.C.) (Jonsered: P. Åströms förlag, 1997).

L. Nevett, House and Society in the Ancient Greek World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

J. Ober, Fortress Attica: Defense of the Athenian Land Frontier, 404-322 B.C. (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1985).

D. S. Robertson, Greek and Roman Architecture 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969).

J. N. Travlos, Pictorial Dictionary of Ancient Athens (New York: Praeger, 1971).

F. E. Winter, Greek Fortifications (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1971).

F. E. Winter, Studies in Hellenistic Architecture (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006).

W. Wrede, Attische Mauern (Athens: Deutsches archäologisches Institut, 1933).

R. E. Wycherley, The Stones of Athens (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Greek architectural orders

Identify the classical orders—the architectural styles developed by the Greeks and Romans used to this day.

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\)

An architectural order describes a style of building. In classical architecture each order is readily identifiable by means of its proportions and profiles, as well as by various aesthetic details. The style of column employed serves as a useful index of the style itself, so identifying the order of the column will then, in turn, situate the order employed in the structure as a whole. The classical orders—described by the labels Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian—do not merely serve as descriptors for the remains of ancient buildings, but as an index to the architectural and aesthetic development of Greek architecture itself.

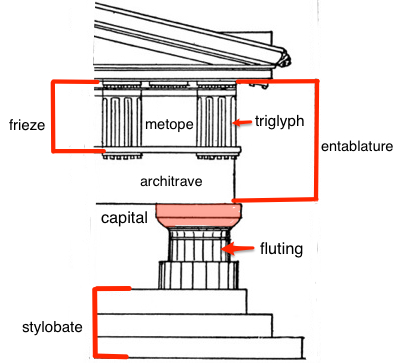

The Doric order

The Doric order is the earliest of the three Classical orders of architecture and represents an important moment in Mediterranean architecture when monumental construction made the transition from impermanent materials (i.e. wood) to permanent materials, namely stone. The Doric order is characterized by a plain, unadorned column capital and a column that rests directly on the stylobate of the temple without a base. The Doric entablature includes a frieze composed of trigylphs (vertical plaques with three divisions) and metopes (square spaces for either painted or sculpted decoration). The columns are fluted and are of sturdy, if not stocky, proportions.

The Doric order emerged on the Greek mainland during the course of the late seventh century B.C.E. and remained the predominant order for Greek temple construction through the early fifth century B.C.E., although notable buildings of the Classical period—especially the canonical Parthenon in Athens—still employ it. By 575 B.C.E the order may be properly identified, with some of the earliest surviving elements being the metope plaques from the Temple of Apollo at Thermon. Other early, but fragmentary, examples include the sanctuary of Hera at Argos, votive capitals from the island of Aegina, as well as early Doric capitals that were a part of the Temple of Athena Pronaia at Delphi in central Greece. The Doric order finds perhaps its fullest expression in the Parthenon (c. 447-432 B.C.E.) at Athens designed by Iktinos and Kallikrates.

The Ionic order

As its names suggests, the Ionic Order originated in Ionia, a coastal region of central Anatolia (today Turkey) where a number of ancient Greek settlements were located. Volutes (scroll-like ornaments) characterize the Ionic capital and a base supports the column, unlike the Doric order. The Ionic order developed in Ionia during the mid-sixth century B.C.E. and had been transmitted to mainland Greece by the fifth century B.C.E. Among the earliest examples of the Ionic capital is the inscribed votive column from Naxos, dating to the end of the seventh century B.C.E.

The monumental temple dedicated to Hera on the island of Samos, built by the architect Rhoikos

c. 570-560 B.C.E., was the first of the great Ionic buildings, although it was destroyed by earthquake in short order. The sixth century B.C.E. Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, a wonder of the ancient world, was also an Ionic design. In Athens the Ionic order influences some elements of the Parthenon (447-432 B.C.E.), notably the Ionic frieze that encircles the cella of the temple. Ionic columns are also employed in the interior of the monumental gateway to the Acropolis known as the Propylaia (c. 437-432 B.C.E.). The Ionic was promoted to an exterior order in the construction of the Erechtheion (c. 421-405 B.C.E.) on the Athenian Acropolis (image below).

The Ionic order is notable for its graceful proportions, giving a more slender and elegant profile than the Doric order. The ancient Roman architect Vitruvius compared the Doric module to a sturdy, male body, while the Ionic was possessed of more graceful, feminine proportions. The Ionic order incorporates a running frieze of continuous sculptural relief, as opposed to the Doric frieze composed of triglyphs and metopes.

The Corinthian order

The Corinthian order is both the latest and the most elaborate of the Classical orders of architecture. The order was employed in both Greek and Roman architecture, with minor variations, and gave rise, in turn, to the Composite order. As the name suggests, the origins of the order were connected in antiquity with the Greek city-state of Corinth where, according to the architectural writer Vitruvius, the sculptor Callimachus drew a set of acanthus leaves surrounding a votive basket (Vitr. 4.1.9-10). In archaeological terms the earliest known Corinthian capital comes from the Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae and dates to c. 427 B.C.E.

The defining element of the Corinthian order is its elaborate, carved capital, which incorporates even more vegetal elements than the Ionic order does. The stylized, carved leaves of an acanthus plant grow around the capital, generally terminating just below the abacus. The Romans favored the Corinthian order, perhaps due to its slender properties. The order is employed in numerous notable Roman architectural monuments, including the Temple of Mars Ultor and the Pantheon in Rome, and the Maison Carrée in Nîmes.

Legacy of the Greek architectural canon

The canonical Greek architectural orders have exerted influence on architects and their imaginations for thousands of years. While Greek architecture played a key role in inspiring the Romans, its legacy also stretches far beyond antiquity. When James “Athenian” Stuart and Nicholas Revett visited Greece during the period from 1748 to 1755 and subsequently published The Antiquities of Athens and Other Monuments of Greece (1762) in London, the Neoclassical revolution was underway. Captivated by Stuart and Revett’s measured drawings and engravings, Europe suddenly demanded Greek forms. Architects the likes of Robert Adam drove the Neoclassical movement, creating buildings like Kedleston Hall, an English country house in Kedleston, Derbyshire. Neoclassicism even jumped the Atlantic Ocean to North America, spreading the rich heritage of Classical architecture even further—and making the Greek architectural orders not only extremely influential, but eternal.

Additional resources:

B. A. Barletta, The Origins of the Greek Architectural Orders (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

H. Berve, G. Gruben and M. Hirmer, Greek temples, theatres, and shrines (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1963).

F. A. Cooper, The Temple of Apollo Bassitas 4 vol. (Princeton N.J.: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1992-1996).

J. J. Coulton, Ancient Greek Architects at Work: Problems of Structure and Design (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press, 1982).

W. B. Dinsmoor, The Architecture of Greece: an Account of its Historic Development 3rd ed. (London: Batsford, 1950).

W. B. Dinsmoor, The Propylaia to the Athenian Akropolis, 1: The predecessors (Princeton NJ: American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1980).

P. Gros, Vitruve et la tradition des traités d’architecture: fabrica et ratiocinatio: recueil d’études (Rome: École française de Rome, 2006).

G. Gruben, “Naxos und Delos. Studien zur archaischen Architektur der Kykladen.” Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 112 (1997): 261–416.

Marie-Christine Hellmann, L’architecture Grecque 3 vol. (Paris: Picard, 2002-2010).

A. Hoffmann, E.-L. Schwander, W. Hoepfner, and G. Brands (eds), Bautechnik der Antike: internationales Kolloquium in Berlin vom 15.-17. Februar 1990 (Diskussionen zur archäologischen Bauforschung; 5), (Mainz am Rhein: P. von Zabern, 1991).

M. Korres, From Pentelicon to the Parthenon: The Ancient Quarries and the Story of a Half-Worked Column Capital of the First Marble Parthenon (Athens: Melissa Publishing House, 1995).

M. Korres, Stones of the Parthenon (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2000).

A. W. Lawrence, Greek Architecture 5th ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996).

D. S. Robertson, Greek and Roman Architecture 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969).

J. Rykwert, The Dancing Column: On Order in Architecture (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996).

E.-L. Schwandner and G. Gruben, Säule und Gebälk: zu Struktur und Wandlungsprozess griechisch-römischer Architektur: Bauforschungskolloquium in Berlin vom 16. bis 18. Juni 1994 (Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1996).

M. Wilson Jones, “Designing the Roman Corinthian Order,” Journal of Roman Archaeology, vol. 2, 1989, pp. 35-69.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Black Figures in Classical Greek Art

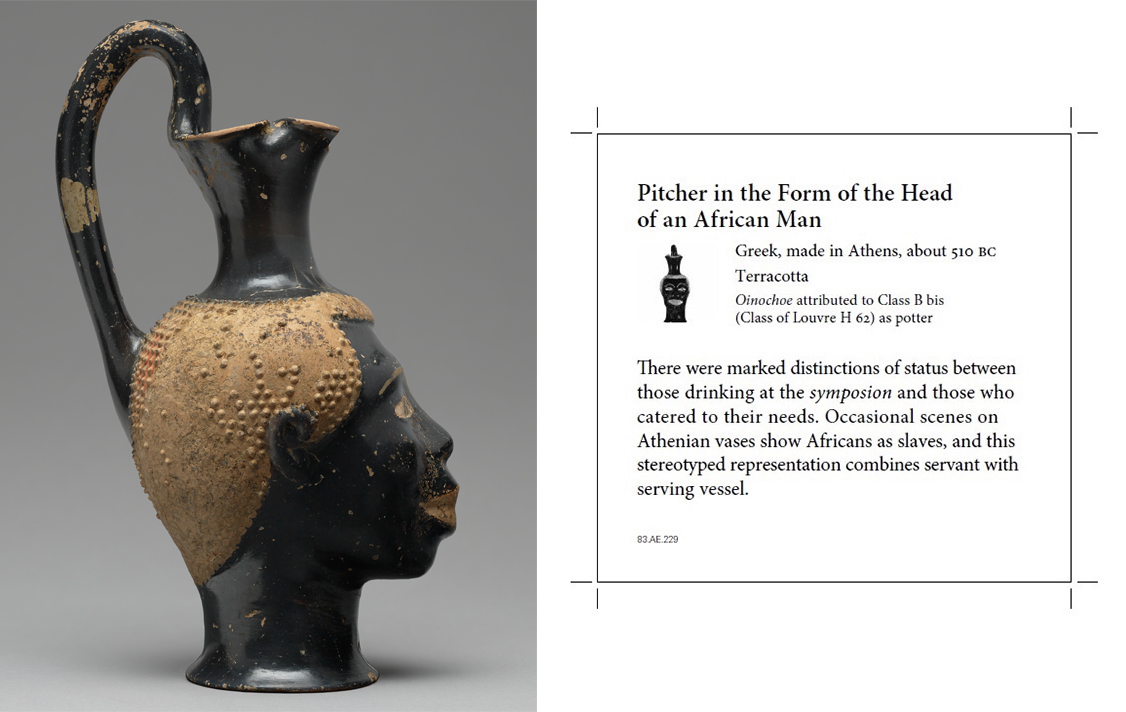

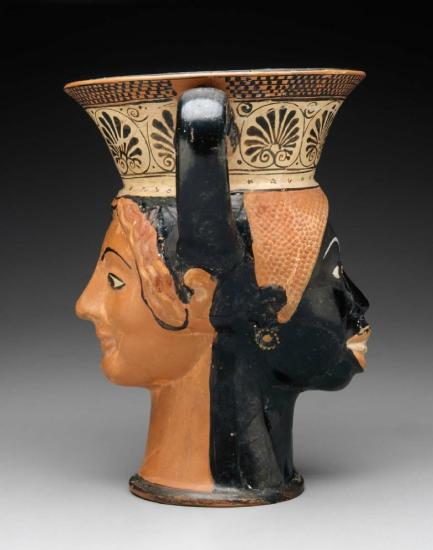

In ancient Greece, men often escaped their daily grind to socialize at a symposium, or formalized drinking party. In the symposium, revelers indulged in numerous leisure activities centered around the consumption of wine. Among the variety of ceramic vessels that were used, pitchers of many shapes and sizes enabled wine pourers to fill the drinkers’ cups. \(^{[1]}\)One example is this oinochoe (a type of wine jug) now on display in the new Athenian vases gallery at the Getty Villa.

This head-shaped wine pitcher invites numerous questions. The first is, quite simply, how to describe it. How can curators responsibly and comprehensively create a label for this pitcher? Is this face best characterized as “black,” “African,” or “black-glazed”?

The term “black” is unsuitable, because it transports our modern color politics into antiquity; the Trans-Atlantic slave trade has permanently mangled any attempt to use this color objectively.

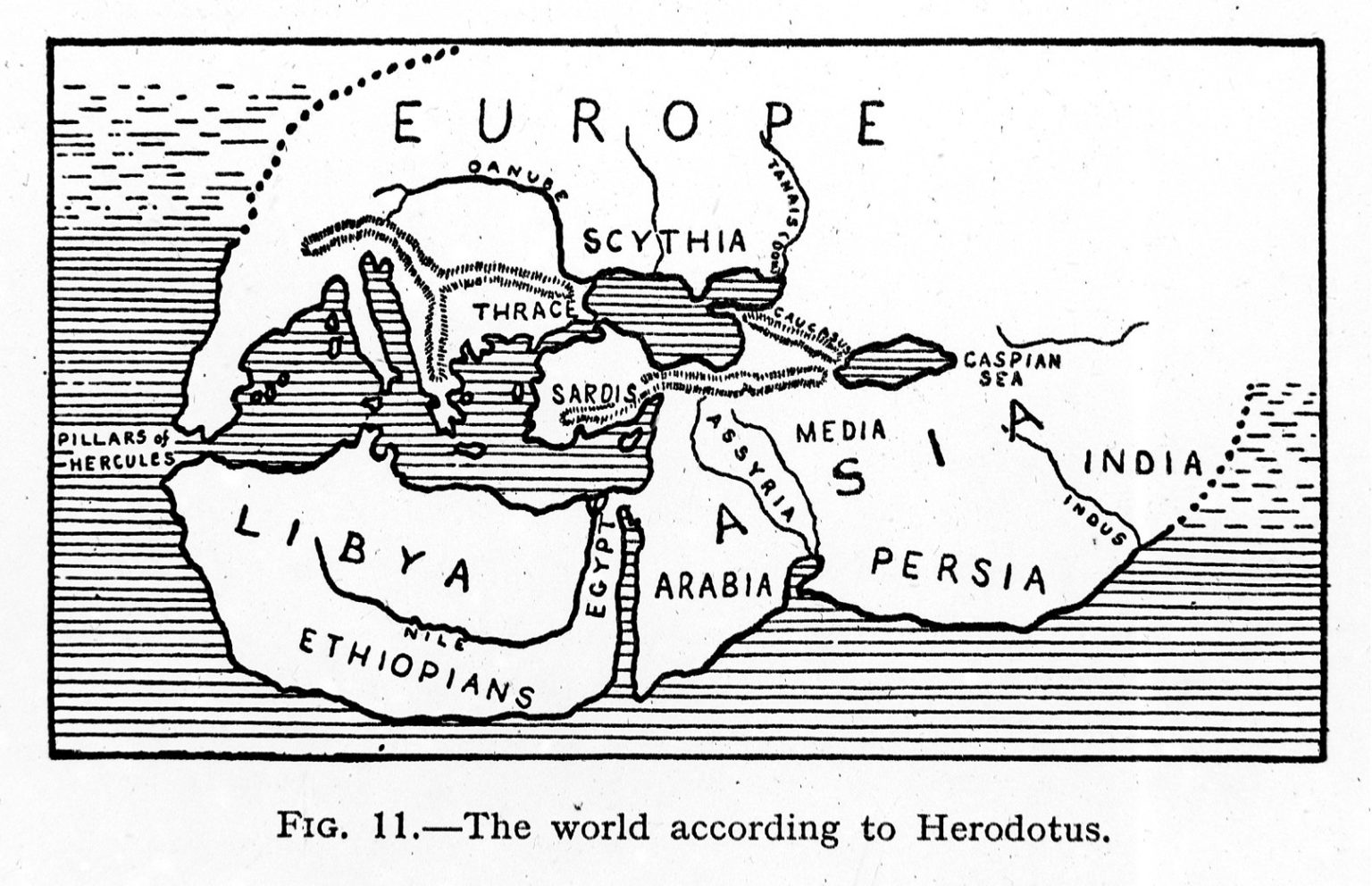

The geographical marker “African” initially seems like a sound alternative. Unlike the historical weight of “black,” using the name of a continent seems to sidestep the retrojection of slavery’s violent history. It also presents a utopian description that unites fifty-four countries and millions of people into a collective entity. To use the word “African” for this pitcher, however, is to irresponsibly project contemporary concerns onto the past. The notion of “Africa” was vague at the time of production of this vessel, around 500 B.C.E.; the Greek term for the region, “Libya,” referred generally to the northern and northeast regions of the continent. “Aithiopian” was another popular term used to describe people with black skin; the etymology of Aithiopia highlights this relationship: aithō (I blaze) + ops (face).

What about our third option to describe this vessel, “black-glazed”? This term softens modern racial thinking by enabling a focus on material composition; the description recognizes color but does not subscribe to any color-based hierarchy. Although it is naïve to imagine that the black-glazed face, paired with full lips and a broad nose, does not evoke comparison with real people, I would argue that “black-glazed” is preferable because it extends beyond its modern politicized counterpart, “Black.”\(^{[2]}\) The hyphen emphasizes its artificial status; the label reflects artistic license rather than historical prejudices.

Now let us contextualize the description of this pitcher. The Getty Villa’s label tells us that “occasional scenes on Athenian vases show Africans as slaves, and this stereotyped representation combines servant and serving vessel.” Art historian François Lissarrague also interprets the black-glazed faces on other drinking cups and pitchers as servants in the symposium. \(^{[3]}\)

Some literary evidence supports this claim; one of the character sketches in the late fourth century B.C.E. Theophrastus’ Characters describes a black person as an exotic servant for a petty man.\^{[4]}\) But other ancient Greek texts contradict this characterization; Homeric epics describe black people as semi-divine creatures whose country was a relaxing oasis for the gods.\(^{[5]}\) Furthermore, visual references on ancient Greek vases depict black people in numerous roles: political allies, musicians, religious worshippers, soldiers, and servants. \(^{[6]}\)

It is dangerous to fold selective history into the discussion without any reflective comments about the speculative work at play here. Although it is plausible that some black people were slaves in the fifth century B.C.E., there is no sure sign that this was the case in all situations.

The need for careful treatment of black people in ancient Greek art extends beyond this pitcher. On the cover of Roman historian Benjamin Isaac’s 2004 book The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity, a troubling scene encourages anachronistic interpretations.

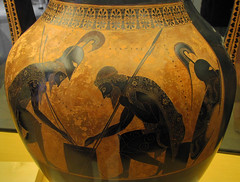

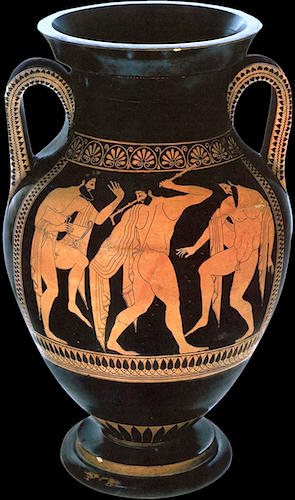

Here, we are confronted with a depiction of a violent encounter between a man and six other men. The person in the middle of the scene looms large and distinct; his upright pose and stark nakedness stand in sharp contrast to the clothed people in contorted positions around him. There are other visual clues that suggest his dominance. All of the men who come into contact with him either writhe under his feet or are firmly in his grasp. They are no match for his strength; he plows through them without hesitation.

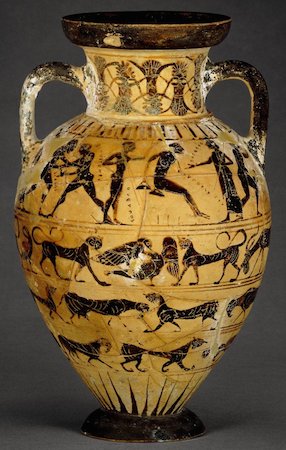

Perhaps in collaboration with Isaac, Princeton University Press (the publishers of this book) chose this image as a cover for an important contribution to the discussion of racism in antiquity. This artistic rendition is based on a modern illustration of a sixth-century B.C.E. black-figure hydria (water jar). [7]

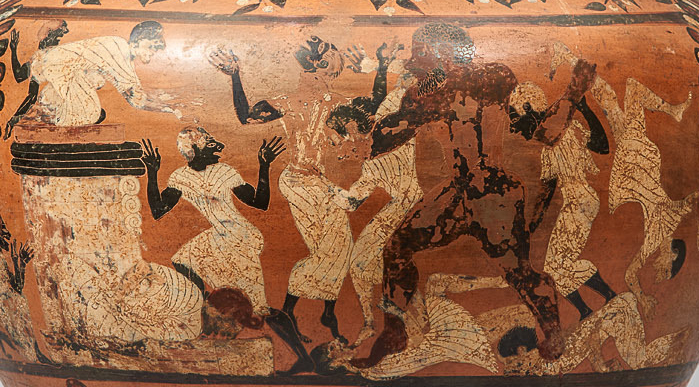

This impressive vase can be seen at the Getty Center in the exhibition Beyond the Nile: Egypt and the Classical World. It depicts Herakles as he resists Egyptians’ attempts to sacrifice him under the orders of the Egyptian king Bousiris. According to ancient Greek mythology, Bousiris received a prophecy that stipulated the sacrifice of a foreigner in order to stop a drought that was destroying his city. When Herakles entered Egypt, Bousiris tried to slaughter him, but the Greek hero fought back and eventually escaped.

Although the visual similarities between the cover and the water vessel above are striking, the ancient image allows for a more sophisticated approach to skin color than the book cover’s partial rendering of the scene. On the vase, black skin is capacious and flexible; it is not limited to those near Herakles. The crouching Egyptian priest on the left of the altar, as well as the Egyptian with raised hands to the right of the altar, have black skin. The black lines framing the scene and the black patterned designs on opposite sides of the scene also destabilize any quick interpretation of this color in antiquity. Skin color is only one element of this scene; the main theme appears to be the inverted violence that has occurred. The fear of the nine men is palpable; one has even climbed on top of the altar meant for Herakles. To add a final twist, Herakles’ skin tone on this jar is dark red. [8] Herakles’ blackness, as it appears today, is due to the worn state of the jar’s surface.

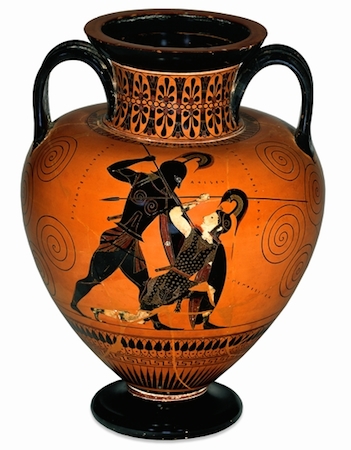

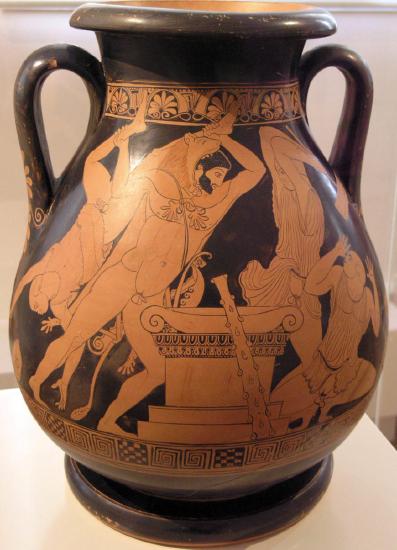

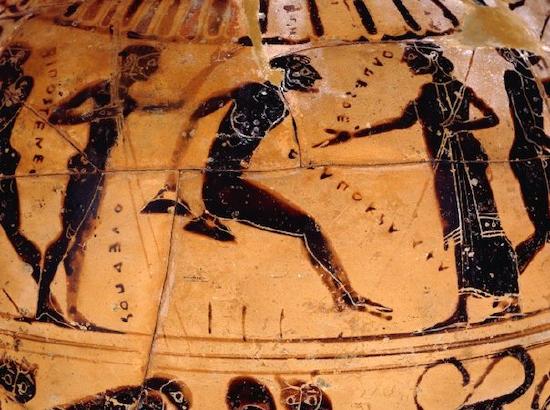

There are numerous examples of this sacrificial scene on ancient Greek pottery. Another depiction portrays Herakles as a figure whose skin color does not differ from those around him.

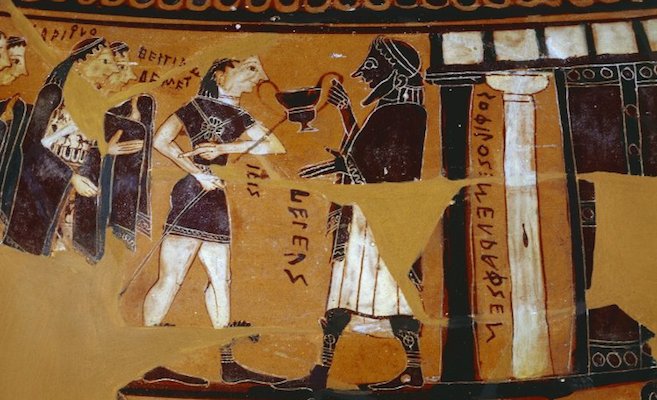

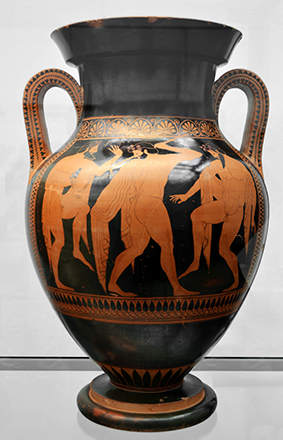

On this fifth-century B.C.E.greece storage jar, Herakles (on the left of the altar) again uses his sheer strength to punish the Egyptians. But there is a different awareness of color dynamics at play on this jar. Rather than a depiction of Herakles with black skin, blackness dominates the background of this vessel. Herakles’ black hair and black beard set him apart from the bald and clean-shaven Egyptians. This does not mean, however, that his chromatic appearance is particularly important in this scene. Instead, blackness literally fades into the background. It offers a visual palette for a powerful scene rather than a reflection of color-based power dynamics. Herakles’ lion-skin cloak and club are more helpful indicators of his identity. [9] In addition, the physiognomy of Herakles marks him as distinct from the Egyptians; his long nose and thin lips stand in contrast to their broad noses and full lips.

Altogether, it is undeniable that the image on Isaac’s cover reproduces an ancient representation of Herakles. But the cover art is also eerily reminiscent of contemporary discourse about Blackness. In particular, it suggests a dangerous connection between violence and the (modern) Black male body. This cover misleads anyone interested in ancient discussions of black skin because the contents of this book do not adequately address this topic. This omission encourages viewers and readers to assume that this image is an accurate representation of black people in Greek antiquity. Barring the caption on the back of the book, the image is presented without any context; people who judge books by their covers will jump to inaccurate conclusions. The permanently violent coding of black skin color is incorrect and irresponsible; there are no historical roots tracing this presumed innate threat.

In sum, museum and academic scholars are key players in the fight for contextualized and equitable perspectives of black people in antiquity; they curate exhibits and write books that greatly influence vast audiences. Preconceived notions of Black people are seared into our country’s collective consciousness; without an overhaul of the “black=slaves in perpetuity” trope, damaging stereotypes become ossified as facts for future generations. This brief examination has revealed ancient Greek art to be an expansive landscape. Ancient Greece’s visual heritage included representations of black people that nimbly provoked and cut across hierarchies. Objects like the sixth-century B.C.E. head-shaped pitcher and water jar discussed above were not part of any chromatic hierarchy because such categories had yet to be codified. Instead, they existed within their own historical and artistic context.

This essay first appeared in the Iris (CC BY 4.0)

Notes:

- Various types of head-shaped vessels were produced around this time; see this example in the form of a woman’s head in the Getty Villa collection.

- I use “Black” to refer to the contemporary, socially constructed group of people, and “black” to designate people who are described as having black skin in ancient Greek literature and art.

- François Lissarrague, “Athenian Image of the Foreigner,” translated by Antonia Nevill. In Thomas Harrison, ed., Greeks and Barbarians (Routledge Press, 2002): 108–9.

- Theophrastus, 21.4.2.

- Iliad 1.423, Odyssey, 1.22-23.

- For more examples, see Frank Snowden Jr. “Aithiopes,” in Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae, Volume I: Aara-Aphlad (Artemis Publishers, 1981): 415-18.

- For a clearer rendition of the colors on this jar, see Perseus Digital Library.

- Jaap M. Hemelrijk, Caeretan Hydriae (Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1984): 52-54.

- Herakles killed and skinned a lion during the first of his Twelve Labors (feats he completed to atone for his madness-induced murder of his family).

Additional resources:

The danger of importing colorblindness and the dream of “White Europe” into antiquity

Insightful blog posts about the diversity of the ancient world by Classicist Rebecca Futo Kennedy

Podcast about race and racism in the fields of Classics and Medieval Studies

Getty Museum’s instructional video about ancient pottery-making

David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates Jr., eds., The Image of the Black in Western Art: From the Pharaohs to the Fall of the Roman Empire (Volume I) (Harvard University Press, 2010).

Rebecca Futo Kennedy, C. Sydnor Roy, and Max L. Goldman, trans., Race and Ethnicity in the Classical World: An Anthology of Primary Sources in Translation (Hackett Publishing, 2013). Selected passages (pp. 111–202) focus on northern and eastern Africa.

Denise McCoskey, Race: Antiquity and Its Legacy (Oxford University Press, 2012).

James H. Dee, “Black Odysseus, White Caesar: When Did ‘White People’ Become ‘White’?,” The Classical Journal 99 (2, 2003/4): 157-67.

Olympic games

Every fourth year between 776 B.C.E. and 395 C.E., the Olympic Games, held in honor of the god Zeus, the supreme god of Greek mythology, attracted people from across Greece. Crowds watched sports such as running, discus-throwing and the long-jump.

Olympia

The sporting events at Olympia were the oldest and most important of the four national Greek athletic festivals. The games were held on an official basis every four years from 776 B.C.E., but they probably originated much earlier. Greek myth credited the hero Herakles with devising the running races at Olympia to celebrate the completion of one of his twelve labors.

Olympia was the most important sanctuary of the god Zeus, and the Games were held in his honor. Sacrifices and gifts were offered, and athletes took oaths to obey the rules before a statue of Zeus. The games were announced by heralds traveling to all the major Greek cities around the Mediterranean, and hostilities were banned during the period around the Games to safeguard those traveling to and from Olympia.

The games at Olympia continued with minor interruptions into early Christian times and were the inspiration for the modern Olympic Games, first staged in Athens in 1896.

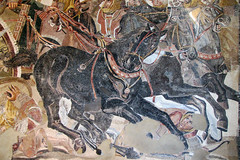

Equestrian Events

Chariot racing was the most popular spectator sport in ancient times. Up to 40 chariots could compete in a race and crashes were common.

In ancient Greece only the wealthy could afford to maintain a chariot and horses. Chariots had been used to carry warriors into battle, and chariot races, along with other sports events, were originally held at the funeral games of heroes, as described in Homer’s Iliad.

Wealthy citizens and Greek statesmen were anxious to win such a prestigious event. They sometimes drove their own chariot, but usually employed a charioteer. The races took place in an arena called the hippodrome. The most dangerous place was at the turning post, where chariot wheels could lock together and there were many crashes.

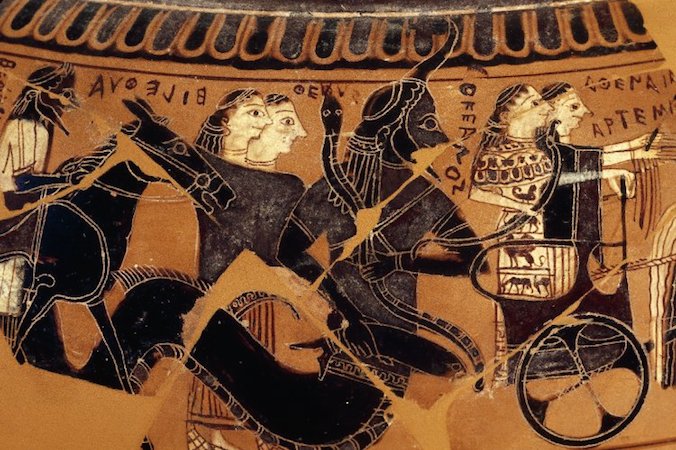

The painter of this vase has been highly successful in creating the illusion of speed as the chariot careers along. A quadriga chariot drawn by four horses is shown, the hair and tunic of the charioteer are blown back, and the manes and tails of the horses fly in the rush of air. The chariot is coming up to a post which may represent the turn or the finish of the race. Both moments would be climaxes.

After the dangers and excitement of the chariot race came the horse- racing. This was hazardous because the track was already churned up, and the jockeys rode without stirrups or saddles, which were not yet invented. The winning horse and its owner were given an enthusiastic reception, and riderless horses that came first past the post were also honored.

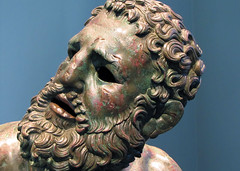

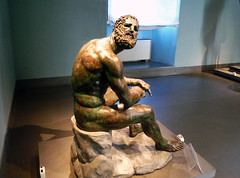

Combat Sports

A big attraction at all the Greek games were the “heavy” events—wrestling, boxing, and the pankration, a type of all-in wrestling. Specialists in the sports could win large sums of money all over the Greek world, once they had proved themselves at Olympia.

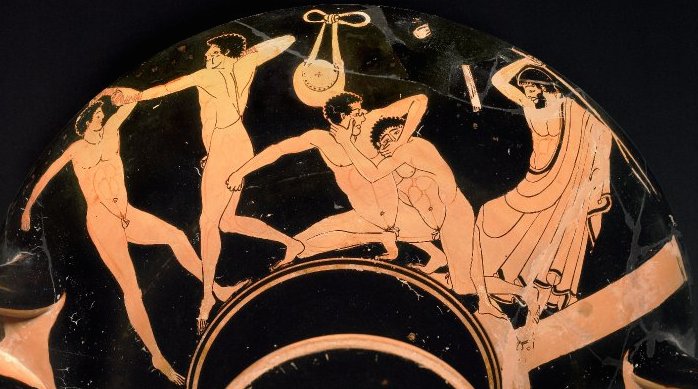

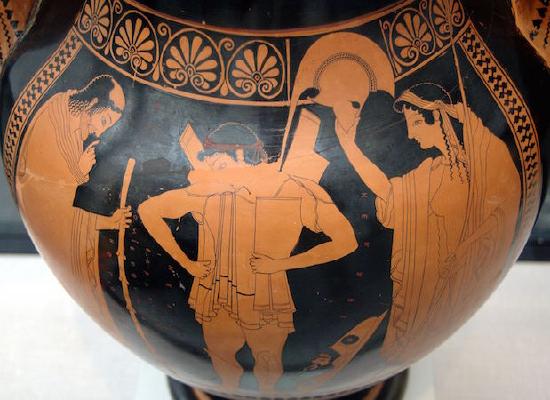

The pankration was a mixture of boxing and wrestling, where almost any tactic was permitted. Only biting and going for an opponent’s eyes were illegal. On the cup above, on the left is a pair of boxers in a bout. In the center is a pair of pancratiasts down on the ground. Above them hangs a discus in a bag. In the center, one pankratiast tries to gouge his opponent’s eye. A bearded trainer steps forward, his forked stick raised over his head to stop the fouls and the fight.

Boxing was considered the most violent sport. There were no separate rounds in a match and the contestants fought until one of them gave in. In ancient Greece thin strips of leather were bound around the boxers’ fists to protect their hands. Boxing gloves were eventually developed, and in the Roman period they were weighted with lead or iron to inflict greater damage.

The boxer on the left has his left arm bent up in front, his right arm back, and there is a dilute line on his cheek. His opponent, facing to the left, is seen in three-quarter back view, his left arm out in front, his right drawn back for a blow. His cheek is heavily marked with relief lines, under the eye and along the cheekbone, to denote swelling.

Wrestling was a sport of great skill which used many of the throws still seen today. It also featured as part of the pentathlon (“pente” means five in Greek while “athlos” means contest, so the ancient pentathlon included five events: discus, javelin, long jump, running and wrestling).

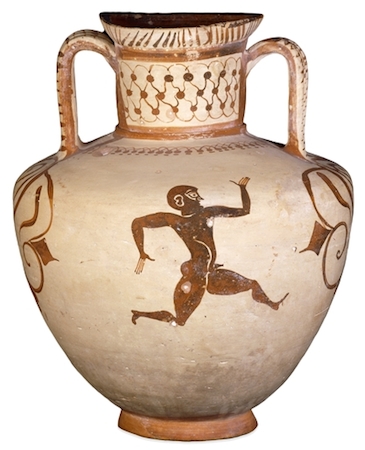

Running

The most ancient and prestigious event at Olympia was the running race along the length of the stadium, a distance of 600 Olympic feet (192.28 meters). The Olympiad (the four-year period up to the next Games) was named after the winner, and dates were recorded by reference to the list of victors. Besides this equivalent of our “two-hundred meter” event, there was a race along two lengths of the track, and a long-distance race of twenty or twenty-four lengths. There was no “marathon,” this was the invention of Baron de Coubertin who revived the Olympic Games in 1896. In all these races the runners made a standing start, from a row of stone slabs set in the track that had grooves cut in them to provide a grip for the toes.

Here, a runner is painted in silhouette, with the few inner markings reserved in the natural colour of the clay. His pose, with arms and legs fully extended and chest thrust out, suggests that he is running at full speed. Most sixth-century vase painters would have surrounded this isolated figure with ornamental friezes or panels, but this artist wisely resisted the temptation.

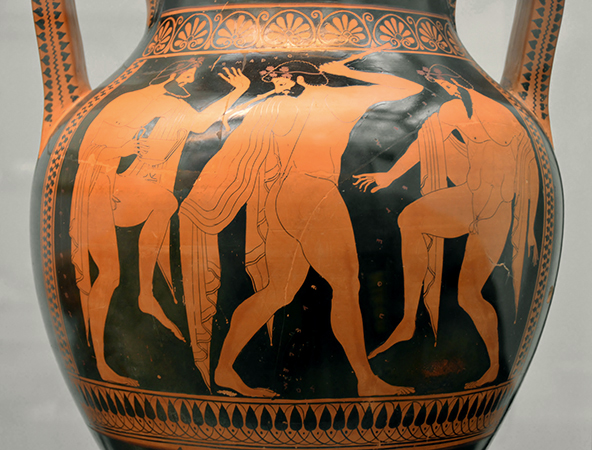

Jumping

This vase has one of the best surviving depictions of the long-jump event at the ancient Olympic Games. There was only the long jump, not the high jump, in Greek athletics. You can see that the athlete in the picture is holding heavy lead or stone jumping weights called halteres. These were swung to increase the length of the jump. You can also see three pegs in the ground which mark the previous jumps.

The athlete is shown on the shoulder of the vase, and is captured in mid-jump, while to the right a trainer urges him on. Beneath the jumper are pegs, which may record his previous jumps or those of other athletes.

In the ancient long jump athletes carried weights that were swung forward on take-off and back just before landing. It’s often said that the weights increased the length of the jump, but it is more likely that they were there for use as a deliberate handicap. Most ancient sport developed as a means of training for warfare, and this exercise would simulate a jump carrying kit. Skill in this sport would be useful for crossing a stream or ravine.

The vase has other scenes related to ancient sporting events, including a discus thrower. To the jumper’s left there is an athlete holding what are possibly javelins and two wrestlers are also shown.

Pentathlon

The pentathlon was made up of five events (discus, jumping, javelin, running and wrestling) which all took place in one afternoon. Running and wrestling also existed as separate events.

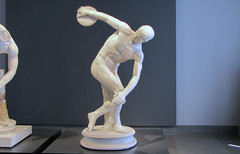

There are differences between the ancient and the modern contests. Greek discus-throwers did not spin round on the spot: they rarely managed throws of more than 30 meters, less than half the modern Olympic record.

In the ancient long-jump, contestants used jumping-weights. These where swung forward on take-off then backward just before landing, to add thrust and gain extra length. Some kind of multiple jump may have been involved.

Javelin-throwing was similar to today’s event, except that a thong was attached to the javelin shaft to add spin and secure a steadier flight.

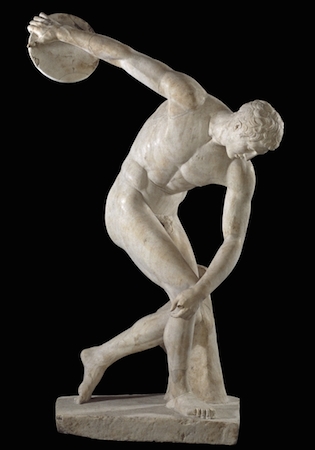

The head on this figure of a discus thrower has been wrongly restored, and should be turned to look towards the discus. The popularity of the sculpture in antiquity was no doubt due to its representation of the athletic ideal. Discus-throwing was the first element in the pentathlon, and while pentathletes were in some ways considered inferior to those athletes who excelled at a particular sport, their physical appearance was much admired.

The Olympic victors

Valuable prizes could be won in athletic contests all over the Greek world, but victory at Olympia brought the greatest prestige. Winning contestants were allowed to put up statues of themselves inside the sanctuary of Zeus to commemorate their victory; many bases for these statues survive. Statues of athletes and statesmen were a prominent feature of Greek cities and sanctuaries. If they won three times they could set up specially commissioned portrait statues which could cost up to ten times the average yearly wage.

Athletes tied a woolen band around their forehead, and sometimes around their arms and legs, as sign of victory. Winners at Olympia received crowns of wild olive, just as Herakles was said to have done when he had run the first races at Olympia with his brothers.

This small engraved sealstone, perhaps originally from a finger ring, shows the winged goddess Nike placing a crown of leaves on the head of a winning athlete. In Greek mythology, the goddess Nike was a messenger of the gods and, more generally, the personification of victory. She was also closely associated with Zeus, god of the Olympic Games, and is often shown in flight, bearing a wreath or a victory ribbon, to crown victorious athletes. The athlete holds a small branch, also symbolic of victory. Whether this sealstone belonged to an athlete or simply a sports enthusiast we shall probably never know.

Statues of Nike featured prominently at Olympia in connection with both sporting and military victories. The victors wreaths associated with Nike were usually made of foliage that could be dried and kept for a long time to preserve the memory of a victory. At Olympia they were made of twigs of olive, sacred to Zeus. Winning athletes were showered with flowers and leaves. This mark of celebration is called phyllobolia and is echoed today in the throwing of confetti and “ticker tape.”

Known as the Daidoumenos (ribbon wearer) this statue shows a triumphant athlete tying a ribbon round his head immediately after a victory. At ancient Greek sports festivals it was the custom to give ribbons to winning athletes. Later, at the awards’ ceremony, the athlete received a wreath of leaves such as olive, laurel or wild celery leaves, depending on the festival. The identity of the athlete and the event he won are not known. He may represent athletic victories in general.

Victor statues were intended to immortalize successful athletes. Sculptors favored bronze for athletic statues, perhaps because it better represented tanned, oiled skin, but many were carved from marble. They were set on bases inscribed with a dedication to a god, the athlete’s name, father’s name, home town and contest.

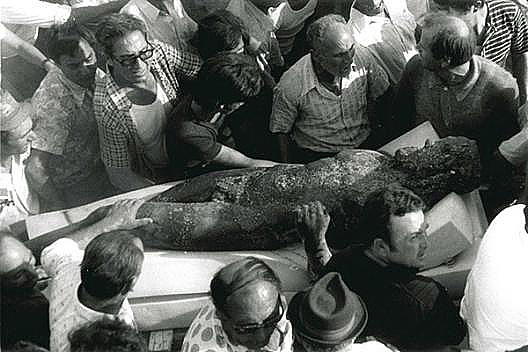

Archaeology at Olympia

Over the centuries the river Alpheios, to the south of the sanctuary, folded and swept away the hippodrome, and the river Kladeios to the west destroyed part of the gymnasium. Following earthquakes and storms, a layer of silt was deposited over the entire site. Olympia lay unnoticed until modern times when an Englishman, Richard Chandler, rediscovered it in 1766.

The German government sponsored full-scale excavations from 1875. The excellent local museum displays many of the remarkable finds, and the German Archaeological Institute in liaison with the Greek Archaeological Service continues to investigate the site to the present day.

Suggested readings:

J. Boardman, Early Greek vase painting (London, Thames and Hudson, 1998).

J. Swaddling, The ancient Olympic Games, 3rd edition (London, The British Museum Press, 2004)

Richard Woff, The Ancient Greek Olympics (Oxford University Press, 2000).

The sealstone with the goddess Nike crowning an athlete at The British Museum

Panathenaic prize amphora of a chariot race at The British Museum

The Townley Discobolus at The British Museum

Black-figured “Tyrrhenian” amphora at The British Museum

Fikellura style amphora with a running man at The British Museum

Marble figure of a victorious athlete (Daidoumenos)

© Trustees of the British Museum

Pottery

Ancient Greek pots represent some of the only ancient Greek painting to survive.

c. 900 - 146 B.C.E.

Greek Vase-Painting, an introduction

Useful for scholars

Pottery is virtually indestructible. Though it may break into smaller pieces (called sherds), these would have to be manually ground into dust in order to be removed from the archaeological record. As such, there is an abundance of material for study, and this is exceptionally useful for modern scholars. In addition to being an excellent tool for dating, pottery enables researchers to locate ancient sites, reconstruct the nature of a site, and point to evidence of trade between groups of people. Moreover, individual pots and their painted decoration can be studied in detail to answer questions about religion, daily life, and society.

Shapes and Themes

Made of terracotta (fired clay), ancient Greek pots and cups, or “vases” as they are normally called, were fashioned into a variety of shapes and sizes (see above), and very often a vessel’s form correlates with its intended function. For example, the krater was used to mix water and wine during a Greek symposion (an all-male drinking party). It allows an individual to pour liquids into its wide opening, stir the contents in its deep bowl, and easily access the mixture with a separate ladle or small jug. Or, the vase known as a hydria was used for collecting, carrying, and pouring water. It features a bulbous body, a pinched spout, and three handles (two at the sides for holding and one stretched along the back for tilting and pouring).

Made of terracotta (fired clay), ancient Greek pots and cups, or “vases” as they are normally called, were fashioned into a variety of shapes and sizes (see above), and very often a vessel’s form correlates with its intended function. For example, the krater was used to mix water and wine during a Greek symposion (an all-male drinking party). It allows an individual to pour liquids into its wide opening, stir the contents in its deep bowl, and easily access the mixture with a separate ladle or small jug. Or, the vase known as a hydria was used for collecting, carrying, and pouring water. It features a bulbous body, a pinched spout, and three handles (two at the sides for holding and one stretched along the back for tilting and pouring).

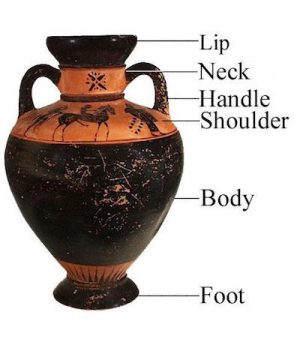

In order to discuss the different zones of vessels, specialists have adopted terms that relate to the parts of the body. The opening of the pot is called the mouth; the stem is referred to as the neck; the slope from the neck to the body is called the shoulder; and the base is known as the foot).

On the exterior, Greek vases exhibit painted compositions that often reflect the style of a certain period. For example, the vessels created during the Geometric Period (c. 900-700 B.C.E.) feature geometric patterns, as seen on the famous Dipylon amphora (below), while those decorated in the Orientalizing Period (c. 700-600 B.C.E.) display animal processions and Near Eastern motifs, as is visible on this early Corinthian amphora (The British Museum).

Later, during the Archaic and Classical Periods (c. 600-323 B.C.E.), vase-paintings primarily display human and mythological activities. These figural scenes can vary widely, from daily life events (e.g., fetching water at the fountain house) to heroic deeds and Homeric tales (e.g., Theseus and the bull, Odysseus and the Sirens), from the world of the gods (e.g., Zeus abducting Ganymede) to theatrical performances and athletic competitions (for example, the Oresteia, chariot racing). While it is important to stress that such painted scenes should not be thought of as photographs that document reality, they can still aid in reconstructing the lives and beliefs of the ancient Greeks.

Techniques, Painters and Inscriptions

To produce the characteristic red and black colors found on vases, Greek craftsmen used liquid clay as paint (termed “slip”) and perfected a complicated three-stage firing process. Not only did the pots have to be stacked in the kiln in a specific manner, but the conditions inside had to be precise. First, the temperature was stoked to about 800° centigrade and vents allowed for an oxidizing environment. At this point, the entire vase turned red in color. Next, by sealing the vents and increasing temperature to around 900-950° centigrade, everything turned black and the areas painted with the slip vitrified (transformed into a glassy substance). Finally, in the last stage, the vents were reopened and oxidizing conditions returned inside the kiln. At this point, the unpainted zones of the vessel became red again while the vitrified slip (the painted areas) retained a glossy black hue. Through the introduction and removal of oxygen in the kiln and, simultaneously, the increase and decrease in temperature, the slip transformed into a glossy black color.

Briefly, ancient Greek vases display several painting techniques, and these are often period specific. During the Geometric and Orientalizing periods (900-600 B.C.E.), painters employed compasses to trace perfect circles and used silhouette and outline methods to delineate shapes and figures (below).

Around 625-600 B.C.E., Athens adopted the black-figure technique (i.e., dark-colored figures on a light background with incised detail). Originating in Corinth almost a century earlier, black-figure uses the silhouette manner in conjunction with added color and incision. Incision involves the removal of slip with a sharp instrument, and perhaps its most masterful application can be found on an amphora by Exekias (below). Often described as Achilles and Ajax playing a game, the seated warriors lean towards the center of the scene and are clothed in garments that feature intricate incised patterning. In addition to displaying more realistically defined figures, black-figure painters took care to differentiate gender with color: women were painted with added white, men remained black.

The red-figure technique was invented in Athens around 525-520 B.C.E. and is the inverse of black-figure (below). Here light-colored figures are set against a dark background. Using added color and a brush to paint in details, red-figure painters watered down or thickened the slip in order to create different effects.

Watered down slip or “dilute glaze” has the appearance of a wash and was used for hair, fur, and anatomy, as exemplified by the sketchy coat of the hare and the youth’s musculature on the interior of this cup by Gorgos (below). When thickened, the slip was used to form so-called “relief lines” or lines raised prominently from the surface, and these were often employed to outline forms. Surprisingly similar to red-figure is the white-ground technique.

Though visually quite different with its polychrome figures on a white-washed background, white-ground requires the craftsman to paint in the details of forms just like red-figure, rather than incise them (see the Kylix below).

Alongside figures and objects, one can sometimes find inscriptions. These identify mythological figures, beautiful men or women contemporaneous with the painter (“kalos” / “kale” inscriptions), and even the painter or potter himself (“egrapsen” / “epoiesen”). Inscriptions, however, are not always helpful. Mimicking the appearance of meaningful text, “nonsense inscriptions” deceive the illiterate viewer by arranging the Greek letters in an incoherent fashion.

Vases and Reception

The overall attractive quality of Greek vases, their relatively small size, and—at one point in time—their easily obtainable nature, led them to be highly coveted collector’s items during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Since the later part of the nineteenth century, however, the study of vases became a scholarly pursuit and their decoration was the obsession of connoisseurs gifted with the ability to recognize and attribute the hands of individual painters.

The most well-known vase connoisseur of the twentieth century, a researcher concerned with attribution, typology, and chronology, was Sir John Davidson Beazley. Interested in Athenian black-, red-figure, and white-ground techniques, Beazley did not favor beautifully painted specimens; he was impartial and studied pieces of varying quality with equal attention. From his tedious and exhaustive examinations, he compiled well-over 1000 painters and groups, and he attributed over 30,000 vases. Although some researchers since Beazley’s death continue to attribute and examine the style of specific painters or groups, vase scholars today also question the technical production of vessels, their archaeological contexts, their local and foreign distribution, and their iconography.

Additional resources:

Ancient Greek vase production and the black-figure technique

From heroes and gods to everyday life, ancient Greek pottery depicted a variety of subjects.

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Used for the storage and shipment of grains, wine, and other goods, as well as in the all-male Greek drinking party, known as the symposium, ancient Greek vases were decorated with a variety of subjects ranging from scenes of everyday life to the tales of heroes and gods. The two most popular techniques of vase decoration were the black-figure technique, so-named because the figures were painted black, and the red-figure technique, in which the figures were left the red color of the clay. The black-figure technique developed around 700 B.C. and remained the most popular Greek pottery style until about 530 B.C., when the red-figure technique was developed, eventually surpassing it in popularity. This video illustrates the techniques used in the making and decorating of a black-figure amphora (storage jar) in the Art Institute of Chicago’s collection.. Video from the Art Institute of Chicago

Making Greek vases

How did ancient Greek potters make and decorate their pottery?

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): In ancient Greece, the phrase “to make pottery” meant to work hard. This video from the J. Paul Getty Museum reveals how the typical Athenian potter prepared clay, threw vases, oversaw firing, and added decoration or employed vase-painters. Video from the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Dipylon Amphora

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

As tall as a person, this pot is covered with geometric patterns and early figural representations.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

<

Terracotta Krater

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

This pot stood above a grave, and the female mourners depicted on it tear out their hair in grief.

Cite this page as: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, "Terracotta Krater," in Smarthistory, April 6, 2017, accessed July 30, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/met-krater/.

Eleusis Amphora

by STEVEN ZUCKER and BETH HARRIS