2.2: Ancient Near East

- Page ID

- 62663

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Ancient Near East

c. 3500 - 400 B.C.E.

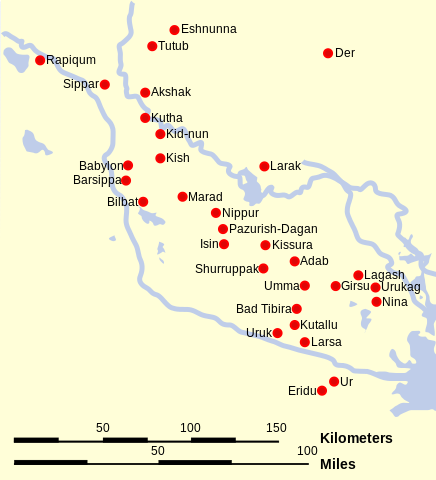

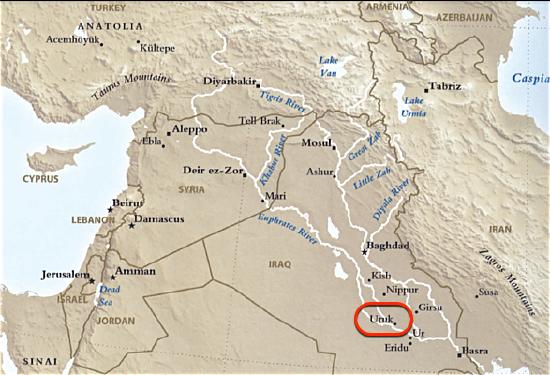

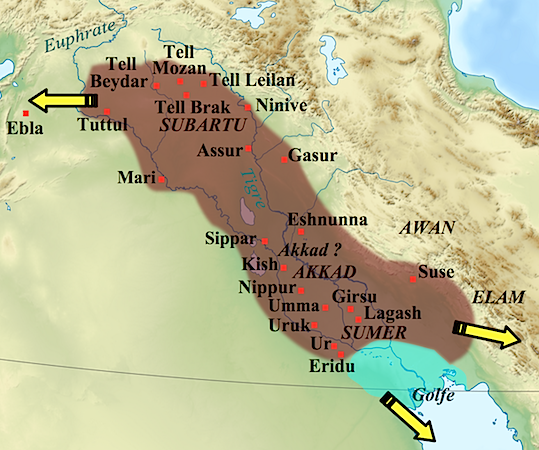

Mesopotamia, the area between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (in modern day Iraq), is often referred to as the Cradle of Civilization because it is one of the first places where complex urban centers grew.

Sumerian

The region of southern Mesopotamia is known as Sumer, and it is in Sumer that we find some of the oldest known cities, including Ur and Uruk.

c. 4000 - 2339 B.C.E.

Sumer, an introduction

Sumer was home to some of the oldest known cities, supported by a focus on agriculture.

The region of southern Mesopotamia is known as Sumer, and it is in Sumer that we find some of the oldest known cities, including Ur and Uruk.

Uruk

Prehistory ends with Uruk, where we find some of the earliest written records. This large city-state (and it environs) was largely dedicated to agriculture and eventually dominated southern Mesopotamia. Uruk perfected Mesopotamian irrigation and administration systems.

An agricultural theocracy

Within the city of Uruk, there was a large temple complex dedicated to Innana, the patron goddess of the city. The City-State’s agricultural production would be “given” to her and stored at her temple. Harvested crops would then be processed (grain ground into flour, barley fermented into beer) and given back to the citizens of Uruk in equal share at regular intervals.

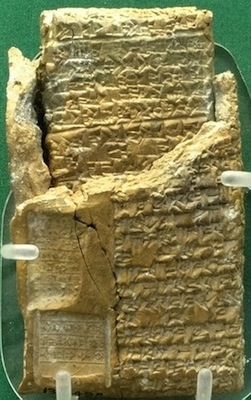

The head of the temple administration, the chief priest of Innana, also served as political leader, making Uruk the first known theocracy. We know many details about this theocratic administration because the Sumerians left numerous documents in the form of tablets written in cuneiform script.

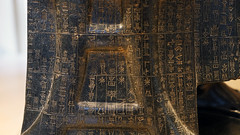

It is almost impossible to imagine a time before writing. However, you might be disappointed to learn that writing was not invented to record stories, poetry, or prayers to a god. The first fully developed written script, cuneiform, was invented to account for something unglamorous, but very important—surplus commodities: bushels of barley, head of cattle, and jars of oil!

The origin of written language (c. 3200 B.C.E.) was born out of economic necessity and was a tool of the theocratic (priestly) ruling elite who needed to keep track of the agricultural wealth of the city-states. The last known document written in the cuneiform script dates to the first century C.E. Only the hieroglyphic script of the Ancient Egyptians lasted longer.

A reed and clay tablet

A single reed, cleanly cut from the banks of the Euphrates or Tigris river, when pressed cut-edge down into a soft clay tablet, will make a wedge shape. The arrangement of multiple wedge shapes (as few as two and as many as ten) created cuneiform characters. Characters could be written either horizontally or vertically, although a horizontal arrangement was more widely used.

Very few cuneiform signs have only one meaning; most have as many as four. Cuneiform signs could represent a whole word or an idea or a number. Most frequently though, they represented a syllable. A cuneiform syllable could be a vowel alone, a consonant plus a vowel, a vowel plus a consonant and even a consonant plus a vowel plus a consonant. There isn’t a sound that a human mouth can make that this script can’t record.

Probably because of this extraordinary flexibility, the range of languages that were written with cuneiform across history of the Ancient Near East is vast and includes Sumerian, Akkadian, Amorite, Hurrian, Urartian, Hittite, Luwian, Palaic, Hatian and Elamite.

Additional resources

Short video from Artefacts about the reconstruction of the Ziggurat

Cylinder seals on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

The Origins of Writing on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

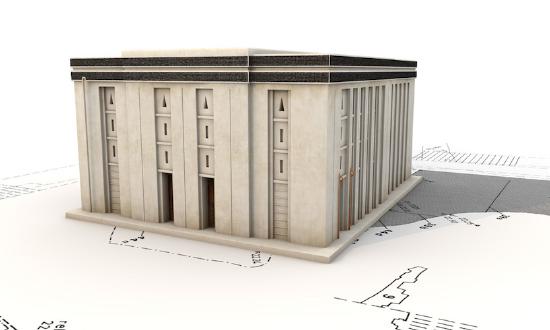

White Temple and ziggurat, Uruk

A gleaming temple built atop a mud-brick platform, it towered above the flat plain of Uruk.

Visible from a great distance

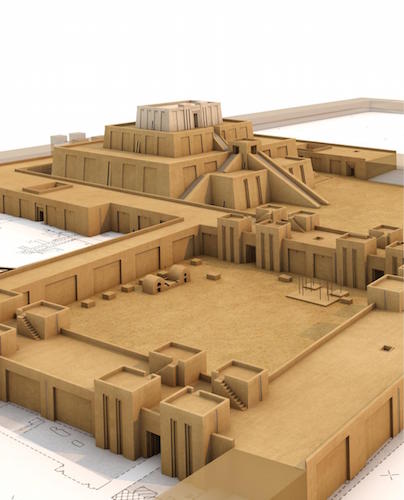

Uruk (modern Warka in Iraq)—where city life began more than five thousand years ago and where the first writing emerged—was clearly one of the most important places in southern Mesopotamia. Within Uruk, the greatest monument was the Anu Ziggurat on which the White Temple was built. Dating to the late 4th millennium B.C.E. (the Late Uruk Period, or Uruk III) and dedicated to the sky god Anu, this temple would have towered well above (approximately 40 feet) the flat plain of Uruk, and been visible from a great distance—even over the defensive walls of the city.

Ziggurats

A ziggurat is a built raised platform with four sloping sides—like a chopped-off pyramid. Ziggurats are made of mud-bricks—the building material of choice in the Near East, as stone is rare. Ziggurats were not only a visual focal point of the city, they were a symbolic one, as well—they were at the heart of the theocratic political system (a theocracy is a type of government where a god is recognized as the ruler, and the state officials operate on the god’s behalf). So, seeing the ziggurat towering above the city, one made a visual connection to the god or goddess honored there, but also recognized that deity’s political authority.

Excavators of the White Temple estimate that it would have taken 1500 laborers working on average ten hours per day for about five years to build the last major revetment (stone facing) of its massive underlying terrace (the open areas surrounding the White Temple at the top of the ziggurat). Although religious belief may have inspired participation in such a project, no doubt some sort of force (corvée labor—unpaid labor coerced by the state/slavery) was involved as well.

The sides of the ziggurat were very broad and sloping but broken up by recessed stripes or bands from top to bottom (see digital reconstruction, above), which would have made a stunning pattern in morning or afternoon sunlight. The only way up to the top of the ziggurat was via a steep stairway that led to a ramp that wrapped around the north end of the Ziggurat and brought one to the temple entrance. The flat top of the ziggurat was coated with bitumen (asphalt—a tar or pitch-like material similar to what is used for road paving) and overlaid with brick, for a firm and waterproof foundation for the White temple. The temple gets its name for the fact that it was entirely white washed inside and out, which would have given it a dazzling brightness in strong sunlight.

The White Temple

The White temple was rectangular, measuring 17.5 x 22.3 meters and, at its corners, oriented to the cardinal points. It is a typical Uruk “high temple (Hochtempel)” type with a tri-partite plan: a long rectangular central hall with rooms on either side (plan). The White Temple had three entrances, none of which faced the ziggurat ramp directly. Visitors would have needed to walk around the temple, appreciating its bright façade and the powerful view, and likely gained access to the interior in a “bent axis” approach (where one would have to turn 90 degrees to face the altar), a typical arrangement for Ancient Near Eastern temples.

The north west and east corner chambers of the building contained staircases (unfinished in the case of the one at the north end). Chambers in the middle of the northeast room suite appear to have been equipped with wooden shelves in the walls and displayed cavities for setting in pivot stones which might imply a solid door was fitted in these spaces. The north end of the central hall had a podium accessible by means of a small staircase and an altar with a fire-stained surface. Very few objects were found inside the White Temple, although what has been found is very interesting. Archaeologists uncovered some 19 tablets of gypsum on the floor of the temple—all of which had cylinder seal impressions and reflected temple accounting. Also, archaeologists uncovered a foundation deposit of the bones of a leopard and a lion in the eastern corner of the Temple (foundation deposits, ritually buried objects and bones, are not uncommon in ancient architecture).

To the north of the White Temple there was a broad flat terrace, at the center of which archaeologists found a huge pit with traces of fire (2.2 x 2.7m) and a loop cut from a massive boulder. Most interestingly, a system of shallow bitumen-coated conduits were discovered. These ran from the southeast and southwest of the terrace edges and entered the temple through the southeast and southwest doors. Archaeologists conjecture that liquids would have flowed from the terrace to collect in a pit in the center hall of the temple.

Additional resources:

Uruk: 5000 year old mega-city (exhibition at the Pergamon Museum, Berlin)

The White Temple and Ziggurat on Art through Time

The White Temple from Artefacts, Berlin

U.S. Department of Defense, Cultural Property Training Resource on Uruk (Modern Warka)

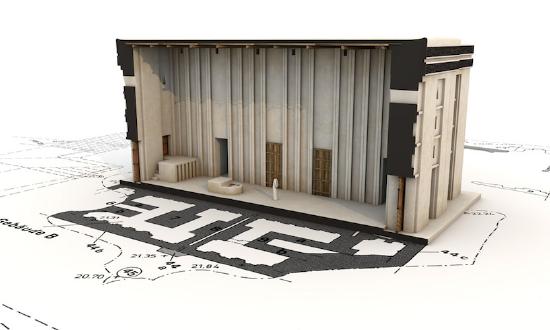

Archaeological reconstructions

Reconstructions of ancient sites or finds can help us to understand the distant past. For non-academics, reconstructions offer a glimpse into that past, a kind of visual accumulation of scientific research communicated by means of images, models or even virtual reality. We see reconstructions in films, museums and magazines to illustrate the stories behind the historical or archaeological facts. For archaeologists like me however, reconstructions are also an important tool to answer unsolved questions and even raise new ones. One field where this is particularly true is the reconstruction of ancient architecture.

Early reconstructions

Since at least medieval times, artists created visual reconstructions drawn from the accounts of travelers or the Bible. Examples of this include the site of Stonehenge or the Tower of Babylon. Since the beginning of archaeology as a science in the mid-19th century, scientific reconstructions based on actual data were made. Of course, the earlier visualizations were more conjectural than later ones, due to the lack of comparable data at that time (for example, the image below).

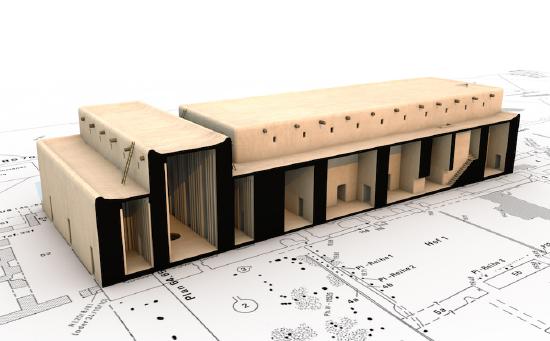

The three building blocks of reconstructions

Since the end of the 19th century, reconstruction drawings evolved to be less conjectural and increasingly based on actual archaeological data as these became available due to increased excavations. Today we can not only look at reconstructions, we can experience them—whether as life-sized physical models or as immersive virtual simulations. But how do we create them? What are they made of? Every reconstruction is basically composed of three building blocks: Primary Sources, Secondary Sources, and Guesswork.

The first step toward a good visualization is to become aware of the archaeological data, the excavated remains—simply everything that has survived. This data is referred to as the Primary Sources—this is the part of the reconstruction we are most certain about. Sometimes we have a lot that survives and sometimes we only have the basic layout of a ground plan (below).

Even when the Primary Sources are utilized, we often have to fill the gaps with Secondary Sources. These sources are composed of architectural parallels, ancient depictions and descriptions, or ethno-archaeological data. So, for example in the case of the Building C in Uruk (above), we know through Primary Sources, that this building was made of mud-bricks (at least the first two rows). We then have to look at other buildings of that time to find out how they were built. In the example above, the layout of the ground-plan shows us that this building was tripartite—a layout well known from this and other sites. We also look at contemporary architecture to understand how mud-brick architecture functions and to find out what certain architectural details might mean. Unfortunately, we don’t have any depictions or textual evidence that can help us with this example. Parallels from later times however show us that the unusual niches in the rooms suggest an important function.

After utilising all the primary and secondary sources, we still need to fill in the gaps. The third part of every reconstruction is simple Guesswork. We obviously need to limit that part as much as we can, but there is always some guesswork involved—no matter how much we research our building. For example, it is rather difficult to decide how high Building C was over 5000 years ago. We therefore have to make an educated guess based, for example, on the estimated length and inclination of staircases within the building. If we are lucky, we can use some primary or secondary sources for that too, but even then, in the end we need to make a subjective decision.

Reconstructions as a scholarly tool

Besides creating these reconstructions to display them in exhibitions, architectural models can also aid archaeological investigations. If we construct ancient architecture using the computer, we not only need to decide every aspect of that particular building, but also the relation to adjoining architecture. Sometimes, the process of reconstructing several buildings and thinking about their interdependence can reveal interesting connections, for example the complicated matter of water disposal off a roof.

These are only random examples, but clearly, the process of architectural reconstruction is a complex one. We, as the creators, need to make sure that the observer understands the problems and uncertainties of a particular reconstruction. It is essential that the viewer understands that these images are not 100% factual. As the archaeologist Simon James has put it: “Every reconstruction is wrong. The only real question is, how wrong is it?”

Additional resources:

ARTEFACTS: Scientific & Archaeological Reconstruction

Nicholas Stanley-Price, The Reconstruction of Ruins: Principles and Practice (2009)

Warka Vase

One of the most precious artifacts from Sumer, the Warka Vase was looted and almost lost forever.

Picturing the ruler

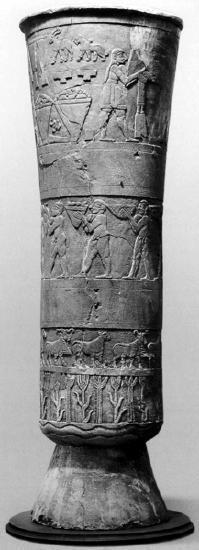

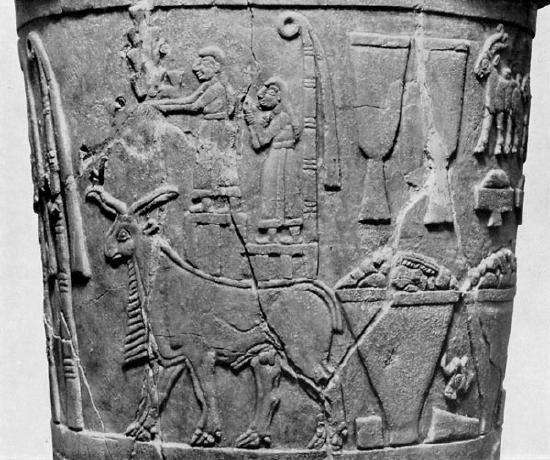

So many important innovations and inventions emerged in the Ancient Near East during the Uruk period (c. 4000 to 3000 B.C.E. and named after the Sumerian city of Uruk). One of these was the use of art to illustrate the role of the ruler and his place in society. The Warka Vase, c. 3000 B.C.E., was discovered at Uruk (Warka is the modern name, Uruk the ancient name), and is probably the most famous example of this innovation. In its decoration we find an example of the cosmology of ancient Mesopotamia.

The vase, made of alabaster and standing over three feet high (just about a meter) and weighing some 600 pounds (about 270 kg), was discovered in 1934 by German excavators working at Uruk in a ritual deposit (a burial undertaken as part of a ritual) in the temple of Inanna, the goddess of love, fertility, and war and the main patron of the city of Uruk. It was one of a pair of vases found in the Inanna temple complex (but the only one on which the image was still legible) together with other valuable objects.

Given the significant size of the Warka Vase, where it was found, the precious material from which it is carved and the complexity of its relief decoration, it was clearly of monumental importance, something to be admired and valued. Though known since its excavation as the Warka “Vase,” that term does little to express the sacredness of this object for the people who lived in Uruk five thousand years ago.

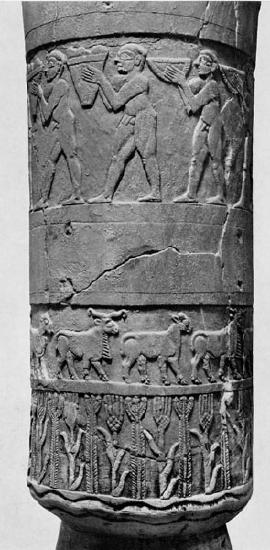

The relief carvings on the exterior of the vase run around its circumference in four parallel bands (or registers, as art historians like to call them) and develop in complexity from the bottom to the top.

Beginning at the bottom, we see a pair of wavy lines from which grow neatly alternating plants that appear to be grain (probably barley) and reeds, the two most important agricultural harvests of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in southern Mesopotamia. There is a satisfying rhythm to this alternation, and one that is echoed in the rhythm of the rams and ewes (male and female sheep) that alternate in the band above this. The sheep march to the right in tight formation, as if being herded—the method of tending this important livestock in the agrarian economy of the Uruk period.

The band above the sheep is a blank and might have featured painted decoration that has since faded away. Above this blank band, a group of nine identical men march to the left. Each holds a vessel in front of his face, and which appear to contain the products of the Mesopotamian agricultural system: fruits, grains, wine, and mead. The men are all naked and muscular and, like the sheep beneath them, are closely and evenly grouped, creating a sense of rhythmic activity. Nude figures in Ancient Near Eastern art are meant to be understood as humble and low status, so we can assume that these men are servants or slaves (the band above, displays the slave owners).

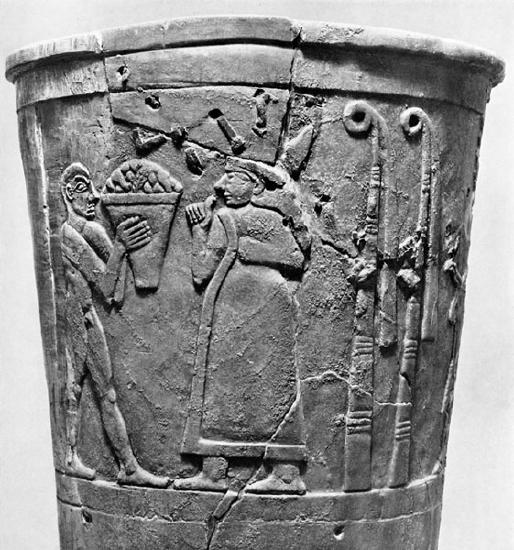

The top band of the vase is the largest, most complex, and least straightforward. It has suffered some damage but enough remains that the scene can be read. The center of the scene appears to depict a man and a woman who face each other. A smaller naked male stands between them holding a container of what looks like agricultural produce which he offers to the woman. The woman, identified as such by her robe and long hair, at one point had an elaborate crown on her head (this piece was broken off and repaired in antiquity).

Behind her are two reed bundles, symbols of the goddess Inanna, whom, it is assumed, the woman represents. The man she faces is nearly entirely broken off, and we are left with only the bottom of his long garment. However, men with similar robes are often found in contemporary seal stone engraving and based upon these, we can reconstruct him as a king with a long skirt, a beard and a head band. The tassels of his skirt are held by another smaller scaled man behind him, a steward or attendant to the king, who wears a short skirt.

The rest of the scene is found behind the reed bundles at the back of Inanna. There we find two horned and bearded rams (one directly behind the other, so the fact that there are two can only be seen by looking at the hooves) carrying platforms on their backs on which statues stand. The statue on the left carries the cuneiform sign for EN, the Sumerian word for chief priest. The statue on the right stands before yet another Inanna reed bundle. Behind the rams is an array of tribute gifts including two large vases which look quite a lot like the Warka Vase itself.

What could this busy scene mean? The simplest way to interpret it is that a king (presumably of Uruk) is celebrating Inanna, the city’s most important divine patron. A more detailed reading of the scene suggests a sacred marriage between the king, acting as the chief priest of the temple, and the goddess—each represented in person as well as in statues. Their union would guarantee for Uruk the agricultural abundance we see depicted behind the rams. The worship of Inanna by the king of Uruk dominates the decoration of the vase. The top illustrates how the cultic duties of the Mesopotamian king as chief priest of the goddess, put him in a position to be responsible for and proprietor of, the agricultural wealth of the city state.

Backstory

The Warka Vase, one of the most important objects in the Iraq National Museum in Baghdad, was stolen in April 2003 with thousands of other priceless ancient artifacts when the museum was looted in the immediate aftermath of the American invasion of Iraq in 2003. The Warka Vase was returned in June of that same year after an amnesty program was created to encourage the return of looted items. The Guardian reported that “The United States army ignored warnings from its own civilian advisers that could have stopped the looting of priceless artifacts in Baghdad….”

Even before the invasion, looting was a growing problem, due to economic uncertainty and widespread unemployment in the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War. According to Dr. Neil Brodie, Senior Research Fellow on the Endangered Archaeology of the Middle East and North Africa project at the University of Oxford, “In the aftermath of that war…as the country descended into chaos, between 1991 and 1994 eleven regional museums were broken into and approximately 3,000 artifacts and 484 manuscripts were stolen….” The vast majority of these have not been returned. And, as Dr. Brodie notes, the most important question may be why no concerted international action was taken to block the sale of objects looted from archaeological sites and cultural institutions during wartime.

Read more about endangered cultural heritage in the Near East in Smarthistory’s ARCHES (At Risk Cultural Heritage Education Series) section.

Additional resources:

Neil Brodie, “The market background to the April 2003 plunder of the Iraq National Museum,” in P. Stone and J. Farchakh Bajjaly (eds), The Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2008), pp. 41-54 (available online here).

Neil Brodie, “Iraq 1990–2004 and the London antiquities market,” in N. Brodie, M. Kersel, C. Luke and K.W. Tubb (eds), Archaeology, Cultural Heritage, and the Antiquities Trade (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2006), pp. 206–26 (available online here).

Neil Brodie, “Focus on Iraq: Spoils of War,” Archaeology (from the Archaeological Institute of America), vol. 56, no. 4 (July/August 2003) (available online here).

On looting in Iraq from SAFE (Saving Antiquities for Everyone)

Documentation on this object in “Lost Treasures from Iraq” from the Oriental Institute in Chicago

Lauren Sandler, “The Thieves of Baghdad,” The Atlantic, November 2004

On looting in Iraq from The Antiquities Coalition

Uruk: The First City on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Standing Male Worshipper (Tell Asmar)

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

One of a group buried in a temple almost 5,000 years ago, this statue’s job was to worship Abu—forever.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Perforated Relief of Ur-Nanshe

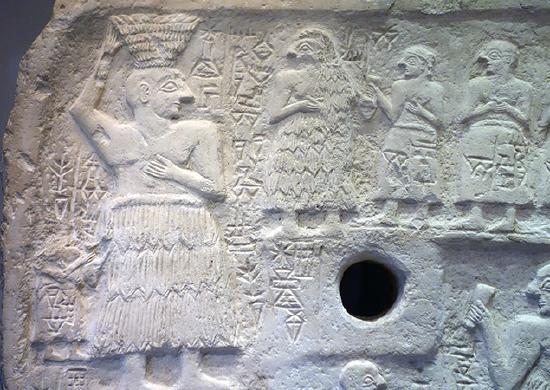

More than 4,000 years ago, Ur-Nanshe, the chief priest and king, displayed his piety and power by building a temple.

Archaeologists believe that the years 2800-2350 B.C.E. in Mesopotamia saw both increased population and a drier climate. This would have increased competition between city-states which would have vied for arable land.

As conflicts increased, the military leadership of temple administrators became more important. Art of this period emphasizes a new combination of piety and raw power in the representation of its leaders. In fact, the representation of human figures becomes more common and more detailed in this era.

This votive plaque, which would have been hung on the wall of a shrine through its central hole, illustrates the chief priest and king of Lagash, Ur-Nanshe, helping to build and then commemorate the opening of a temple of Ningirsu, the patron god of his city. The plaque was excavated at the Girsu. There is some evidence that Girsu was then the capital of the city-state of Lagash.

The top portion of the plaque depicts Ur-Nanshe helping to bring mud bricks to the building site accompanied by his wife and sons. The bottom shows Ur-Nanshe seated at a banquet, enjoying a drink, again accompanied by his sons. In both, he wears the traditional tufted woolen skirt called the kaunakes and shows off his broad muscular chest and arms.

Additional resources

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Cylinder seals

Signed with a cylinder seal

Cuneiform was used for official accounting, governmental and theological pronouncements and a wide range of correspondence. Nearly all of these documents required a formal “signature,” the impression of a cylinder seal.

A cylinder seal is a small pierced object, like a long round bead, carved in reverse (intaglio) and hung on strings of fiber or leather. These often beautiful objects were ubiquitous in the Ancient Near East and remain a unique record of individuals from this era. Each seal was owned by one person and was used and held by them in particularly intimate ways, such as strung on a necklace or bracelet.

When a signature was required, the seal was taken out and rolled on the pliable clay document, leaving behind the positive impression of the reverse images carved into it. However, some seals were valued not for the impression they made, but instead, for the magic they were thought to possess or for their beauty.

The first use of cylinder seals in the Ancient Near East dates to earlier than the invention of cuneiform, to the Late Neolithic period (7600–6000 B.C.E.) in Syria. However, what is most remarkable about cylinder seals is their scale and the beauty of the semi-precious stones from which they were carved. The images and inscriptions on these stones can be measured in millimeters and feature incredible detail.

The stones from which the cylinder seals were carved include agate, chalcedony, lapis lazuli, steatite, limestone, marble, quartz, serpentine, hematite and jasper; for the most distinguished there were seals of gold and silver. To study Ancient Near Eastern cylinder seals is to enter a uniquely beautiful, personal and detailed miniature universe of the remote past, but one which was directly connected to a vast array of individual actions, both mundane and momentous.

Why cylinder seals are interesting

Art historians are particularly interested in cylinder seals for at least two reasons. First, it is believed that the images carved on seals accurately reflect the pervading artistic styles of the day and the particular region of their use. In other words, each seal is a small time capsule of what sorts of motifs and styles were popular during the lifetime of the owner. These seals, which survive in great numbers, offer important information to understand the developing artistic styles of the Ancient Near East.

The second reason why art historians are interested in cylinder seals is because of the iconography (the study of the content of a work of art). Each character, gesture and decorative element can be “read” and reflected back on the owner of the seal, revealing his or her social rank and even sometimes the name of the owner. Although the same iconography found on seals can be found on carved stelae, terra cotta plaques, wall reliefs and paintings, its most complete compendium exists on the thousands of seals which have survived from antiquity.

Standard of Ur

Intentionally buried as part of an elaborate ritual, this ornate object tells us so much, but also too little.

The city of Ur

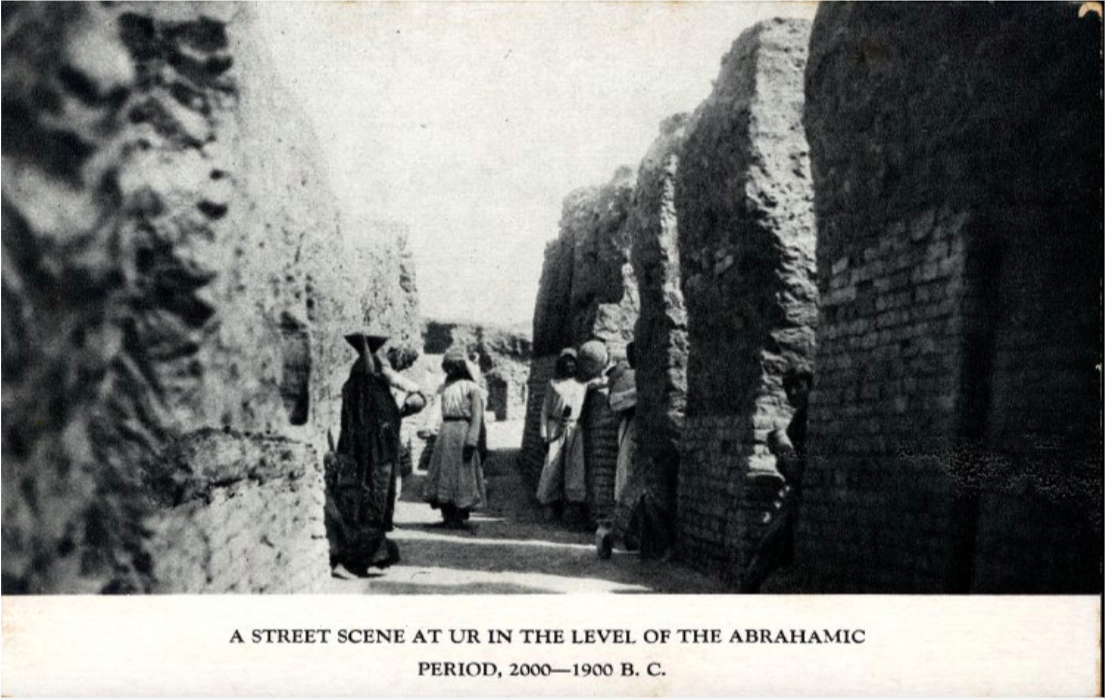

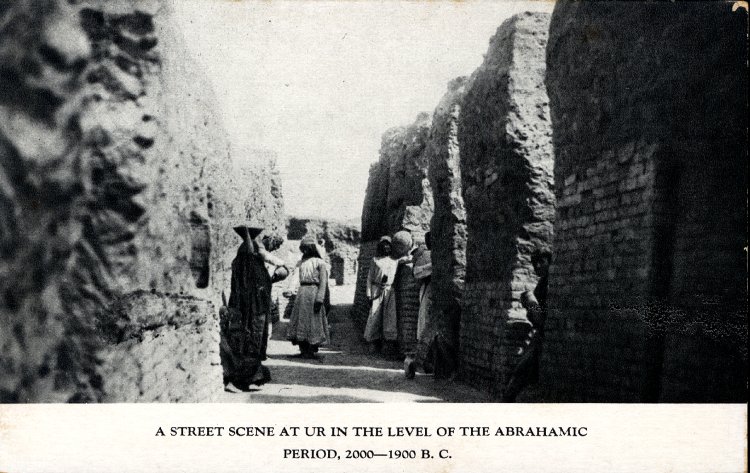

Known today as Tell el-Muqayyar, the “Mound of Pitch,” the site was occupied from around 5000 B.C.E. to 300 B.C.E. Although Ur is famous as the home of the Old Testament patriarch Abraham (Genesis 11:29-32), there is no actual proof that Tell el-Muqayyar was identical with “Ur of the Chaldees.” In antiquity the city was known as Urim.

The main excavations at Ur were undertaken from 1922-34 by a joint expedition of The British Museum and the University Museum, Pennsylvania, led by Leonard Woolley. At the center of the settlement were mud brick temples dating back to the fourth millennium B.C.E. At the edge of the sacred area a cemetery grew up which included burials known today as the Royal Graves. An area of ordinary people’s houses was excavated in which a number of street corners have small shrines. But the largest surviving religious buildings, dedicated to the moon god Nanna, also include one of the best preserved ziggurats, and were founded in the period 2100-1800 B.C.E. For some of this time Ur was the capital of an empire stretching across southern Mesopotamia. Rulers of the later Kassite and Neo-Babylonian empires continued to build and rebuild at Ur. Changes in both the flow of the River Euphrates (now some ten miles to the east) and trade routes led to the eventual abandonment of the site.

The royal graves of Ur

Close to temple buildings at the center of the city of Ur, sat a rubbish dump built up over centuries. Unable to use the area for building, the people of Ur started to bury their dead there. The cemetery was used between about 2600-2000 B.C.E. and hundreds of burials were made in pits. Many of these contained very rich materials.

In one area of the cemetery a group of sixteen graves was dated to the mid-third millennium. These large, shaft graves were distinct from the surrounding burials and consisted of a tomb, made of stone, rubble and bricks, built at the bottom of a pit. The layout of the tombs varied, some occupied the entire floor of the pit and had multiple chambers. The most complete tomb discovered belonged to a lady identified as Pu-abi from the name carved on a cylinder seal found with the burial.

The majority of graves had been robbed in antiquity but where evidence survived the main burial was surrounded by many human bodies. One grave had up to seventy-four such sacrificial victims. It is evident that elaborate ceremonies took place as the pits were filled in that included more human burials and offerings of food and objects. The excavator, Leonard Woolley thought the graves belonged to kings and queens. Another suggestion is that they belonged to the high priestesses of Ur.

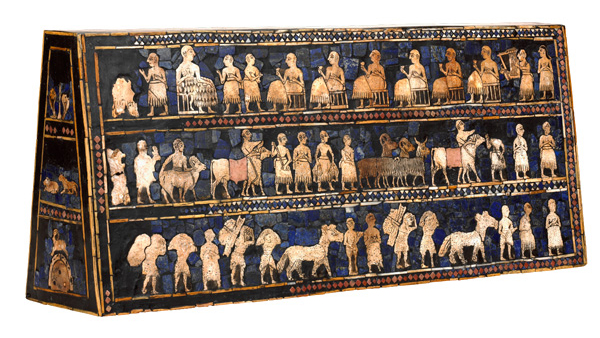

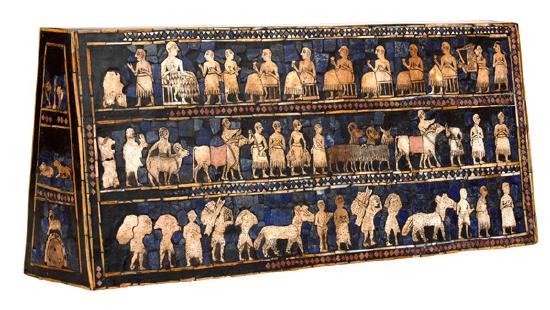

The Standard of Ur

This object was found in one of the largest graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, lying in the corner of a chamber above the right shoulder of a man. Its original function is not yet understood.

Leonard Woolley, the excavator at Ur, imagined that it was carried on a pole as a standard, hence its common name. Another theory suggests that it formed the soundbox of a musical instrument.

When found, the original wooden frame for the mosaic of shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli had decayed, and the two main panels had been crushed together by the weight of the soil. The bitumen acting as glue had disintegrated and the end panels were broken. As a result, the present restoration is only a best guess as to how it originally appeared.

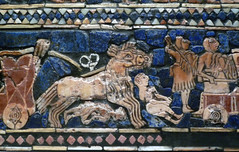

The main panels are known as “War” and “Peace.” “War” shows one of the earliest representations of a Sumerian army. Chariots, each pulled by four donkeys, trample enemies; infantry with cloaks carry spears; enemy soldiers are killed with axes, others are paraded naked and presented to the king who holds a spear.

The “Peace” panel depicts animals, fish and other goods brought in procession to a banquet. Seated figures, wearing woolen fleeces or fringed skirts, drink to the accompaniment of a musician playing a lyre. Banquet scenes such as this are common on cylinder seals of the period, such as on the seal of the “Queen” Pu-abi, also in the British Museum (see image above).

Queen’s Lyre

Leonard Woolley discovered several lyres in the graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. This was one of two that he found in the grave of “Queen” Pu-abi. Along with the lyre, which stood against the pit wall, were the bodies of ten women with fine jewelry, presumed to be sacrificial victims, and numerous stone and metal vessels. One woman lay right against the lyre and, according to Woolley, the bones of her hands were placed where the strings would have been.

The wooden parts of the lyre had decayed in the soil, but Woolley poured plaster of Paris into the depression left by the vanished wood and so preserved the decoration in place. The front panels are made of lapis lazuli, shell and red limestone originally set in bitumen. The gold mask of the bull decorating the front of the sounding box had been crushed and had to be restored. While the horns are modern, the beard, hair and eyes are original and made of lapis lazuli.

This musical instrument was originally reconstructed as part of a unique “harp-lyre,” together with a harp from the burial, now also in The British Museum. Later research showed that this was a mistake. A new reconstruction, based on excavation photographs, was made in 1971-72.

Suggested readings:

J. Aruz, Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus (New York, 2003).

D. Collon, Ancient Near Eastern Art (London, 1995).

H. Crawford, Sumer and Sumerians (Cambridge, 2004).

N. Postgate, Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History (London, 1994).

M. Roaf, Cultural atlas of Mesopotamia (New York, 1990).

C.L. Woolley and P.R.S. Moorey, Ur of the Chaldees, revised edition (Ithaca, New York, Cornell University Press, 1982).

N. Yoffee, Myths of the Archaic State: Evolution of the Earliest Cities, States, and Civilization (Cambridge, 2005).

R. Zettler, and L. Horne, (eds.) Treasures from the Royal Tomb at Ur (Philadelphia, 1998).

Related objects in the collection of the British Museum

© Trustees of the British Museum

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Standard of Ur and other objects from the Royal Graves

At the center of Ur, a rubbish dump grew over the centuries—it evolved into a cemetery for the elite.

The city of Ur

Known today as Tell el-Muqayyar, the “Mound of Pitch,” the site was occupied from around 5000 B.C.E. to 300 B.C.E. Although Ur is famous as the home of the Old Testament patriarch Abraham (Genesis 11:29-32), there is no actual proof that Tell el-Muqayyar was identical with “Ur of the Chaldees.” In antiquity the city was known as Urim.

The main excavations at Ur were undertaken from 1922-34 by a joint expedition of The British Museum and the University Museum, Pennsylvania, led by Leonard Woolley. At the center of the settlement were mud brick temples dating back to the fourth millennium B.C.E. At the edge of the sacred area a cemetery grew up which included burials known today as the Royal Graves. An area of ordinary people’s houses was excavated in which a number of street corners have small shrines. But the largest surviving religious buildings, dedicated to the moon god Nanna, also include one of the best preserved ziggurats, and were founded in the period 2100-1800 B.C.E. For some of this time Ur was the capital of an empire stretching across southern Mesopotamia. Rulers of the later Kassite and Neo-Babylonian empires continued to build and rebuild at Ur. Changes in both the flow of the River Euphrates (now some ten miles to the east) and trade routes led to the eventual abandonment of the site.

The royal graves of Ur

Close to temple buildings at the center of the city of Ur, sat a rubbish dump built up over centuries. Unable to use the area for building, the people of Ur started to bury their dead there. The cemetery was used between about 2600-2000 B.C.E. and hundreds of burials were made in pits. Many of these contained very rich materials.

In one area of the cemetery a group of sixteen graves was dated to the mid-third millennium. These large, shaft graves were distinct from the surrounding burials and consisted of a tomb, made of stone, rubble and bricks, built at the bottom of a pit. The layout of the tombs varied, some occupied the entire floor of the pit and had multiple chambers. The most complete tomb discovered belonged to a lady identified as Pu-abi from the name carved on a cylinder seal found with the burial.

The majority of graves had been robbed in antiquity but where evidence survived the main burial was surrounded by many human bodies. One grave had up to seventy-four such sacrificial victims. It is evident that elaborate ceremonies took place as the pits were filled in that included more human burials and offerings of food and objects. The excavator, Leonard Woolley thought the graves belonged to kings and queens. Another suggestion is that they belonged to the high priestesses of Ur.

The Standard of Ur

This object was found in one of the largest graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, lying in the corner of a chamber above the right shoulder of a man. Its original function is not yet understood.

Leonard Woolley, the excavator at Ur, imagined that it was carried on a pole as a standard, hence its common name. Another theory suggests that it formed the soundbox of a musical instrument.

When found, the original wooden frame for the mosaic of shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli had decayed, and the two main panels had been crushed together by the weight of the soil. The bitumen acting as glue had disintegrated and the end panels were broken. As a result, the present restoration is only a best guess as to how it originally appeared.

The main panels are known as “War” and “Peace.” “War” shows one of the earliest representations of a Sumerian army. Chariots, each pulled by four donkeys, trample enemies; infantry with cloaks carry spears; enemy soldiers are killed with axes, others are paraded naked and presented to the king who holds a spear.

The “Peace” panel depicts animals, fish and other goods brought in procession to a banquet. Seated figures, wearing woolen fleeces or fringed skirts, drink to the accompaniment of a musician playing a lyre. Banquet scenes such as this are common on cylinder seals of the period, such as on the seal of the “Queen” Pu-abi, also in the British Museum (see image above).

Queen’s Lyre

Leonard Woolley discovered several lyres in the graves in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. This was one of two that he found in the grave of “Queen” Pu-abi. Along with the lyre, which stood against the pit wall, were the bodies of ten women with fine jewelry, presumed to be sacrificial victims, and numerous stone and metal vessels. One woman lay right against the lyre and, according to Woolley, the bones of her hands were placed where the strings would have been.

The wooden parts of the lyre had decayed in the soil, but Woolley poured plaster of Paris into the depression left by the vanished wood and so preserved the decoration in place. The front panels are made of lapis lazuli, shell and red limestone originally set in bitumen. The gold mask of the bull decorating the front of the sounding box had been crushed and had to be restored. While the horns are modern, the beard, hair and eyes are original and made of lapis lazuli.

This musical instrument was originally reconstructed as part of a unique “harp-lyre,” together with a harp from the burial, now also in The British Museum. Later research showed that this was a mistake. A new reconstruction, based on excavation photographs, was made in 1971-72.

Suggested readings:

J. Aruz, Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus (New York, 2003).

D. Collon, Ancient Near Eastern Art (London, 1995).

H. Crawford, Sumer and Sumerians (Cambridge, 2004).

N. Postgate, Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History (London, 1994).

M. Roaf, Cultural atlas of Mesopotamia (New York, 1990).

C.L. Woolley and P.R.S. Moorey, Ur of the Chaldees, revised edition (Ithaca, New York, Cornell University Press, 1982).

N. Yoffee, Myths of the Archaic State: Evolution of the Earliest Cities, States, and Civilization (Cambridge, 2005).

R. Zettler, and L. Horne, (eds.) Treasures from the Royal Tomb at Ur (Philadelphia, 1998).

Related objects in the collection of the British Museum

© Trustees of the British Museum

Akkadian

The Akkadian Empire was begun by Sargon, a man from a lowly family who rose to power and founded the royal city of Akkad (Akkad has not yet been located, though one theory puts it under modern Baghdad).

c. 2334 - 2193 B.C.E.

Akkad, an introduction

Founded by the famed Sargon the Great, Akkad was a powerful military empire.

Akkad

Competition between Akkad in the north and Ur in the south created two centralized regional powers at the end of the third millennium (c. 2334–2193 B.C.E.).

This centralization was military in nature and the art of this period generally became more martial. The Akkadian Empire was begun by Sargon, a man from a lowly family who rose to power and founded the royal city of Akkad (Akkad has not yet been located, though one theory puts it under modern Baghdad).

Head of an Akkadian Ruler

This image of an unidentified Akkadian ruler (some say it is Sargon, but no one knows) is one of the most beautiful and terrifying images in all of Ancient Near Eastern art. The life-sized bronze head shows in sharp geometric clarity, locks of hair, curled lips and a wrinkled brow. Perhaps more awesome than the powerful and somber face of this ruler is the violent attack that mutilated it in antiquity.

Ur

The kingdom of Akkad ends with internal strife and invasion by the Gutians from the Zagros mountains to the northeast. The Gutians were ousted in turn and the city of Ur, south of Uruk, became dominant. King Ur-Nammu established the third dynasty of Ur, also referred to as the Ur III period.

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Naram-Sin leads his victorious army up a mountain, as vanquished Lullubi people fall before him.

This monument depicts the Akkadian victory over the Lullubi Mountain people. In the 12th century B.C.E., a thousand years after it was originally made, the Elamite king, Shutruk-Nahhunte, attacked Babylon and, according to his later inscription, the stele was taken to Susa in what is now Iran. A stele is a vertical stone monument or marker often inscribed with text or relief carving.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Cylinder seal with a modern impression

by The Metropolitan Museum of Art

See an ancient cylinder seal used 4000 years after it was made, and learn about its dynastic symbolism.

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Cylinder seal and modern impression: nude bearded hero wrestling with a water buffalo; bull-man wrestling with lion, c. 2250–2150 B.C.E., Akkadian, Serpentine, 1.42″ / 3.61 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Neo-Sumerian/Ur III

Seated Gudea holding temple plan

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Seated Gudea holding Temple Plan, known as “Architect with Plan,” c. 2100 B.C.E. (Neo-Sumerian/Ur III period), from Girsu (modern Telloh, Iraq), diorite, 93 x 41 x 61 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

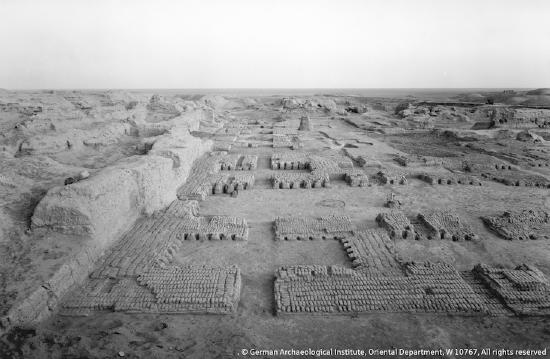

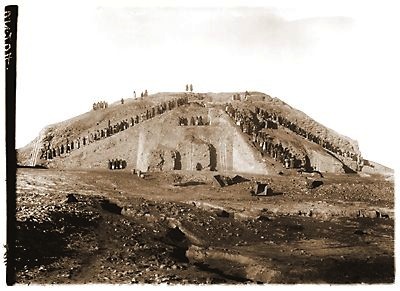

Ziggurat of Ur

The great Ziggurat of Ur has been reconstructed twice, in antiquity and in the 1980s—what’s left of the original?

The Great Ziggurat

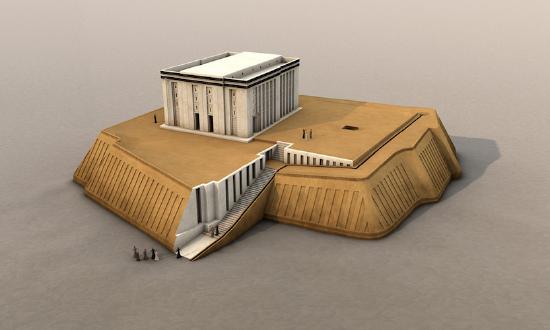

The ziggurat is the most distinctive architectural invention of the Ancient Near East. Like an ancient Egyptian pyramid, an ancient Near Eastern ziggurat has four sides and rises up to the realm of the gods. However, unlike Egyptian pyramids, the exterior of Ziggurats were not smooth but tiered to accommodate the work which took place at the structure as well as the administrative oversight and religious rituals essential to Ancient Near Eastern cities. Ziggurats are found scattered around what is today Iraq and Iran, and stand as an imposing testament to the power and skill of the ancient culture that produced them.

One of the largest and best-preserved ziggurats of Mesopotamia is the great Ziggurat at Ur. Small excavations occurred at the site around the turn of the twentieth century, and in the 1920s Sir Leonard Woolley, in a joint project with the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia and the British Museum in London, revealed the monument in its entirety.

What Woolley found was a massive rectangular pyramidal structure, oriented to true North, 210 by 150 feet, constructed with three levels of terraces, standing originally between 70 and 100 feet high. Three monumental staircases led up to a gate at the first terrace level. Next, a single staircase rose to a second terrace which supported a platform on which a temple and the final and highest terrace stood. The core of the ziggurat is made of mud brick covered with baked bricks laid with bitumen, a naturally occurring tar. Each of the baked bricks measured about 11.5 x 11.5 x 2.75 inches and weighed as much as 33 pounds. The lower portion of the ziggurat, which supported the first terrace, would have used some 720,000 baked bricks. The resources needed to build the Ziggurat at Ur are staggering.

Moon goddess Nanna

The Ziggurat at Ur and the temple on its top were built around 2100 B.C.E. by the king Ur-Nammu of the Third Dynasty of Ur for the moon goddess Nanna, the divine patron of the city state. The structure would have been the highest point in the city by far and, like the spire of a medieval cathedral, would have been visible for miles around, a focal point for travelers and the pious alike. As the Ziggurat supported the temple of the patron god of the city of Ur, it is likely that it was the place where the citizens of Ur would bring agricultural surplus and where they would go to receive their regular food allotments. In antiquity, to visit the ziggurat at Ur was to seek both spiritual and physical nourishment.

Clearly the most important part of the ziggurat at Ur was the Nanna temple at its top, but this, unfortunately, has not survived. Some blue glazed bricks have been found which archaeologists suspect might have been part of the temple decoration. The lower parts of the ziggurat, which do survive, include amazing details of engineering and design. For instance, because the unbaked mud brick core of the temple would, according to the season, be alternatively more or less damp, the architects included holes through the baked exterior layer of the temple allowing water to evaporate from its core. Additionally, drains were built into the ziggurat’s terraces to carry away the winter rains.

Hussein’s assumption

The Ziggurat at Ur has been restored twice. The first restoration was in antiquity. The last Neo-Babylonian king, Nabodinus, apparently replaced the two upper terraces of the structure in the 6th century B.C.E. Some 2400 years later in the 1980s, Saddam Hussein restored the façade of the massive lower foundation of the ziggurat, including the three monumental staircases leading up to the gate at the first terrace. Since this most recent restoration, however, the Ziggurat at Ur has experienced some damage. During the recent war led by American and coalition forces, Saddam Hussein parked his MiG fighter jets next to the Ziggurat, believing that the bombers would spare them for fear of destroying the ancient site. Hussein’s assumptions proved only partially true as the ziggurat sustained some damage from American and coalition bombardment.

Babylonian

The city of Babylon on the River Euphrates in southern Iraq first came to prominence as the royal city of King Hammurabi, and then again during the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

c. 1850 B.C.E. - 539 B.C.E.

Babylonia, an introduction

On the River Euphrates

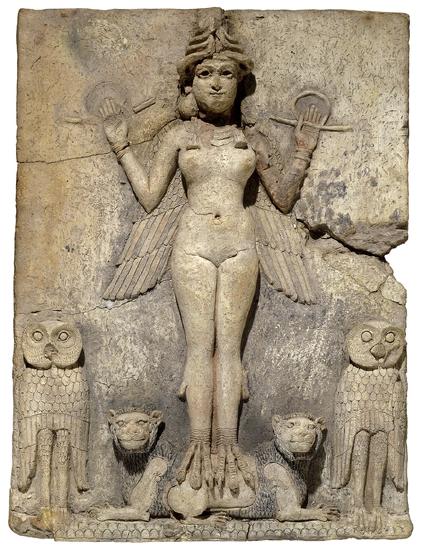

The city of Babylon on the River Euphrates in southern Iraq is mentioned in documents of the late third millennium B.C.E. and first came to prominence as the royal city of King Hammurabi (about 1790-1750 B.C.E.). He established control over many other kingdoms stretching from the Persian Gulf to Syria. The British Museum holds one of the iconic artworks of this period, the so-called “Queen of the Night.”

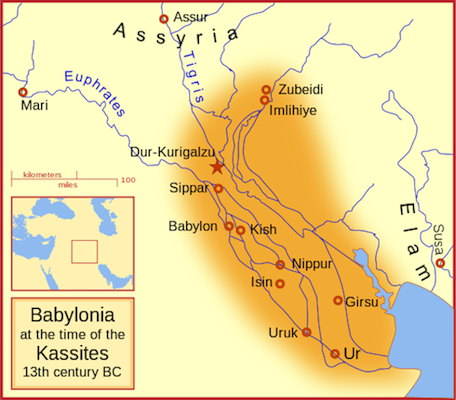

From around 1500 B.C.E. a dynasty of Kassite kings took control in Babylon and unified southern Iraq into the kingdom of Babylonia. The Babylonian cities were the centers of great scribal learning and produced writings on divination, astrology, medicine and mathematics. The Kassite kings corresponded with the Egyptian Pharaohs as revealed by cuneiform letters found at Amarna in Egypt, now in the British Museum.

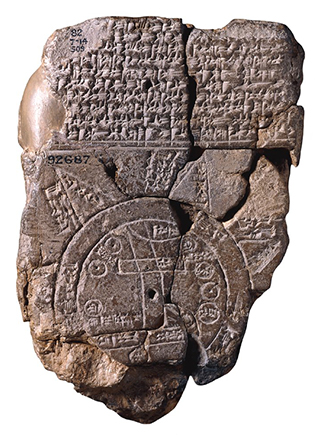

Babylonia had an uneasy relationship with its northern neighbor Assyria and opposed its military expansion. In 689 B.C.E. Babylon was sacked by the Assyrians but as the city was highly regarded it was restored to its former status soon after. Other Babylonian cities also flourished; scribes in the city of Sippar probably produced the famous “Map of the World” (see image below).

Babylonian kings

After 612 B.C.E. the Babylonian kings Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar II were able to claim much of the Assyrian empire and rebuilt Babylon on a grand scale. Nebuchadnezzar II rebuilt Babylon in the sixth century B.C.E. and it became the largest ancient settlement in Mesopotamia. There were two sets of fortified walls and massive palaces and religious buildings, including the central ziggurat tower. Nebuchadnezzar is also credited with the construction of the famous “Hanging Gardens.” However, the last Babylonian king Nabonidus (555-539 B.C.E.) was defeated by Cyrus II of Persia and the country was incorporated into the vast Achaemenid Persian Empire.

New Threats

Babylon remained an important center until the third century B.C.E., when Seleucia-on-the-Tigris was founded about ninety kilometers to the north-east. Under Antiochus I (281-261 B.C.E.) the new settlement became the official Royal City and the civilian population was ordered to move there. Nonetheless a village existed on the old city site until the eleventh century AD. Babylon was excavated by Robert Koldewey between 1899 and 1917 on behalf of the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft. Since 1958 the Iraq Directorate-General of Antiquities has carried out further investigations. Unfortunately, the earlier levels are inaccessible beneath the high water table. Since 2003, our attention has been drawn to new threats to the archaeology of Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq.

For two thousand years the myth of Babylon has haunted the European imagination. The Tower of Babel and the Hanging Gardens, Belshazzar’s Feast and the Fall of Babylon have inspired artists, writers, poets, philosophers and film makers.

Visiting Babylon

by Dr. Beth Harris, Lisa Ackerman and World Monuments Fund

Even today with international tourism waning in the face of military threats, Iraqis regularly visit this famous site.

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): This video was produced in cooperation with the World Monuments Fund.

The Babylonian mind

What do the 60-minute clock and the zodiac have in common? The answer lies in ancient Babylon.

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Video from The British Museum.

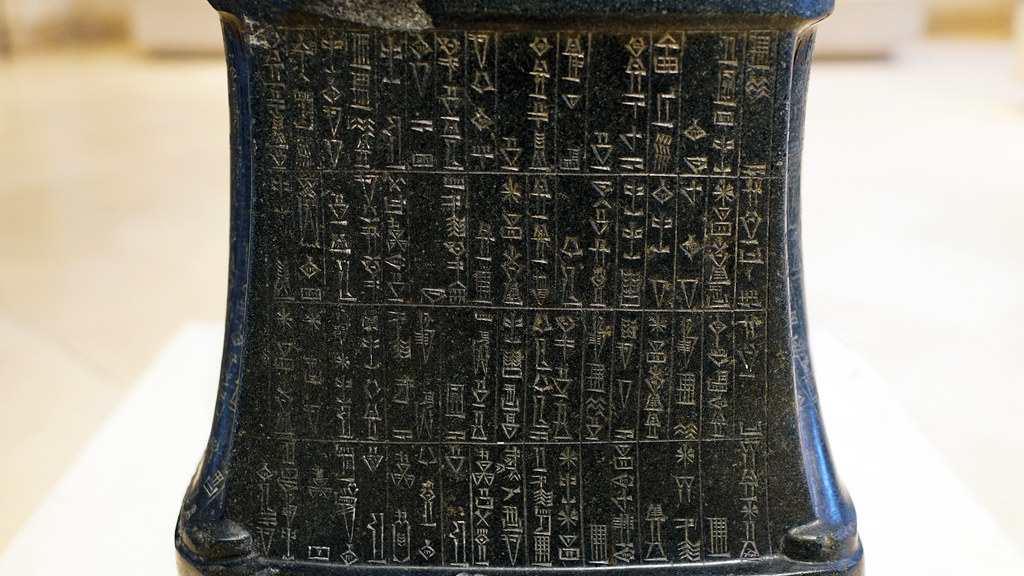

Law Code Stele of King Hammurabi

Law is at the heart of modern civilization, and is often based on principles listed here nearly 4,000 years ago.

A stele is a vertical stone monument or marker often inscribed with text or with relief carving.

Hammurabi of the city state of Babylon conquered much of northern and western Mesopotamia and by 1776 B.C.E., he is the most far-reaching leader of Mesopotamian history, describing himself as “the king who made the four quarters of the earth obedient.” Documents show Hammurabi was a classic micro-manager, concerned with all aspects of his rule, and this is seen in his famous legal code, which survives in partial copies on this stele in the Louvre and on clay tablets (a stele is a vertical stone monument or marker often inscribed with text or with relief carving). We can also view this as a monument presenting Hammurabi as an exemplary king of justice.

What is interesting about the representation of Hammurabi on the legal code stele is that he is seen as receiving the laws from the god Shamash, who is seated, complete with thunderbolts coming from his shoulders. The emphasis here is Hammurabi’s role as pious theocrat, and that the laws themselves come from the god.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Ishtar Gate and Neo-Babylonian art and architecture

“I, Nebuchadnezzar … magnificently adorned them with luxurious splendor for all mankind to behold in awe.”

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate and Processional Way, Babylon, c. 575 B.C.E., glazed mud brick (Pergamon Museum, Berlin)

The chronology of Mesopotamia is complicated. Scholars refer to places (Sumer, for example) and peoples (the Babylonians), but also empires (Babylonia) and unfortunately for students of the Ancient Near East these organizing principles do not always agree. The result is that we might, for example, speak of the very ancient Babylonians starting in the 1800s B.C.E. and then also the Neo-Babylonians more than a thousand years later. What came in between you ask? Well, quite a lot, but mostly the Kassites and the Assyrians.

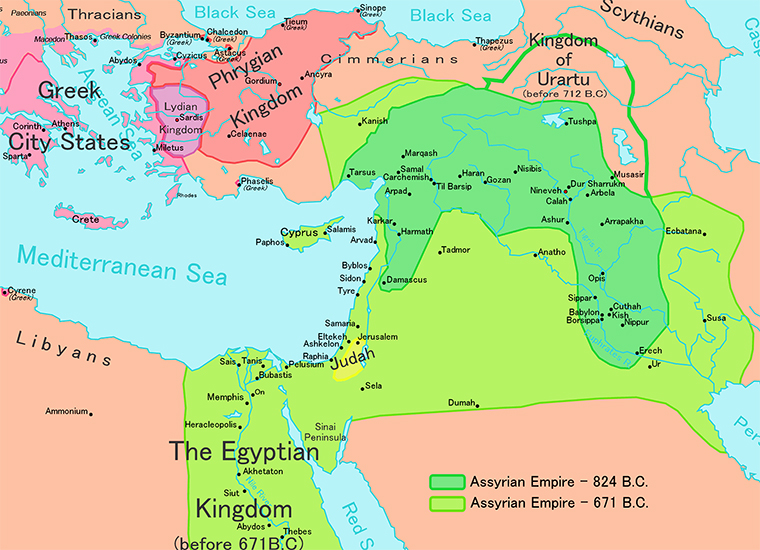

The Assyrian Empire which had dominated the Near East came to an end at around 600 B.C.E. due to a number of factors including military pressure by the Medes (a pastoral mountain people, again from the Zagros mountain range), the Babylonians, and possibly also civil war.

A Neo-Babylonian dynasty

The Babylonians rose to power in the late 7th century and were heirs to the urban traditions which had long existed in southern Mesopotamia. They eventually ruled an empire as dominant in the Near East as that held by the Assyrians before them.

This period is called Neo-Babylonian (or new Babylonia) because Babylon had also risen to power earlier and became an independent city-state, most famously during the reign of King Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.E.).

In the art of the Neo-Babylonian Empire we see an effort to invoke the styles and iconography of the 3rd millennium rulers of Babylonia. In fact, one Neo-Babylonian king, Nabonidus, found a statue of Sargon of Akkad, set it in a temple and provided it with regular offerings.

Architecture

The Neo-Babylonians are most famous for their architecture, notably at their capital city, Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar (604-561 B.C.E.) largely rebuilt this ancient city including its walls and seven gates. It is also during this era that Nebuchadnezzar purportedly built the “Hanging Gardens of Babylon” for his wife because she missed the gardens of her homeland in Media (modern day Iran). Though mentioned by ancient Greek and Roman writers, the “Hanging Gardens” may, in fact, be legendary.

The Ishtar Gate (today in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin) was the most elaborate of the inner city gates constructed in Babylon in antiquity. The whole gate was covered in lapis lazuli glazed bricks which would have rendered the façade with a jewel-like shine. Alternating rows of lion and cattle march in a relief procession across the gleaming blue surface of the gate.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Towers of Babel

Artists have depicted the Tower of Babel throughout the ages, a symbol of the extraordinary—but it did exist.

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Video from The British Museum.

Kassite art: Unfinished Kudurru

The Kassites controlled Babylonia for 400 years—now all that remains are these carved boundary stones.

Artistic exchange

During the 2nd millennium, the region of Mesopotamia, with Assyria in the north and Babylonia in the south, together with Egypt and the Hittite lands in what is now modern Turkey, grew strong and exercised surprisingly harmonious political relations.

For art, this meant an easy exchange of ideas and techniques, and surviving texts reflect the development of “guilds” of craftsmen, such as jewelers, scribes and architects.

Babylonia at this time was held by the Kassites, originally from the Zagros mountains to the north, who sought to imitate Mesopotamian styles of art. Kudurru (boundary markers) are the only significant remains of the Kassites, many of which show Kassite gods and activities translated into the visual style of Mesopotamia.

Combining cultures

This Kudurru, considered unfinished because it lacks an inscription, would have marked the boundary of a plot of land, and probably would have listed the owner and even the person to whom the land was leased.

Although an object made and intended for Kassite use, it bears Babylonian style and imagery, especially the multiple strips or registers of characters and the stately procession of gods and lions.

The Kassites eventually succumbed to the general collapse of Mesopotamia around 1200 B.C.E. This regional collapse affected states as far away as mainland Greece, and as great as Egypt. This is a period characterized by famine, widespread political instability, roving mercenaries and, most likely, plague. It is often referred to as the first Dark Ages.

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Assyrian

The Assyrian empire dominated Mesopotamia and all of the Near East for the first half of the first millennium.

1365 - 609 B.C.E.

Assyria, an introduction

Led by aggressive warrior kings, Assyria dominated the fertile crescent for half a millennia, amassing vast wealth.

A military culture

The Assyrian empire dominated Mesopotamia and all of the Near East for the first half of the first millennium B.C.E., led by a series of highly ambitious and aggressive warrior kings. Assyrian society was entirely military, with men obliged to fight in the army at any time. State offices were also under the purview of the military.

Indeed, the culture of the Assyrians was brutal, the army seldom marching on the battlefield but rather terrorizing opponents into submission who, once conquered, were tortured, raped, beheaded, and flayed with their corpses publicly displayed. The Assyrians torched enemies’ houses, salted their fields, and cut down their orchards.

Luxurious palaces

As a result of these fierce and successful military campaigns, the Assyrians acquired massive resources from all over the Near East which made the Assyrian kings very rich. The palaces were on an entirely new scale of size and glamour; one contemporary text describes the inauguration of the palace of Kalhu, built by Assurnasirpal II (who reigned in the early 9th century), to which almost 70,000 people were invited to banquet.

Some of this wealth was spent on the construction of several gigantic and luxurious palaces spread throughout the region. The interior public reception rooms of Assyrian palaces were lined with large scale carved limestone reliefs which offer beautiful and terrifying images of the power and wealth of the Assyrian kings and some of the most beautiful and captivating images in all of ancient Near Eastern art.

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): This silent video reconstructs the Northwest Palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud (near modern Mosul in northern Iraq) as it would have appeared during his reign in the ninth century B.C.E. The video moves from the outer courtyards of the palace into the throne room and beyond into more private spaces, perhaps used for rituals.( Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art). According to news sources, this important archaeological site was destroyed with bulldozers in March 2015 by the militants who occupy large portions of Syria and Iraq.

Feats of bravery

Like all Assyrian kings, Ashurbanipal decorated the public walls of his palace with images of himself performing great feats of bravery, strength and skill. Among these he included a lion hunt in which we see him coolly taking aim at a lion in front of his charging chariot, while his assistants fend off another lion attacking at the rear.

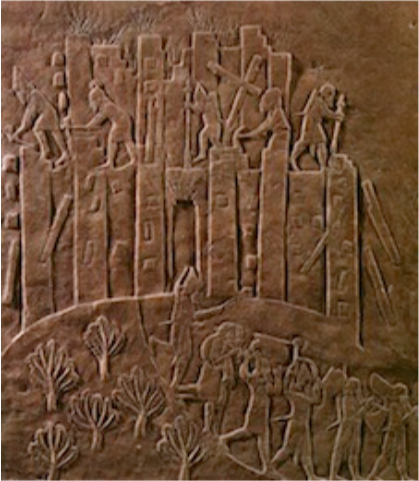

The destruction of Susa

One of the accomplishments Ashurbanipal was most proud of was the total destruction of the city of Susa.

In this relief, we see Ashurbanipal’s troops destroying the walls of Susa with picks and hammers while fire rages within the walls of the city.

Military victories & exploits

In the Central Palace at Nimrud, the Neo-Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III illustrates his military victories and exploits, including the siege of a city in great detail.

In this scene we see one soldier holding a large screen to protect two archers who are taking aim. The topography includes three different trees and a roaring river, most likely setting the scene in and around the Tigris or Euphrates rivers.

Assyrian Sculpture

by The British Museum and Arathi.Menon

Leveraging their enormous wealth, the Assyrians built great temples and palaces full of art, all paid for by conquest.

Although Assyrian civilization, centred in the fertile Tigris valley of northern Iraq, can be traced back to at least the third millennium B.C.E., some of its most spectacular remains date to the first millennium B.C.E. when Assyria dominated the Middle East.

Ashurnasirpal II

The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 B.C.E.) established Nimrud as his capital. Many of the principal rooms and courtyards of his palace were decorated with gypsum slabs carved in relief with images of the king as high priest and as victorious hunter and warrior. Many of these are displayed in the British Museum.

Ashurnasirpal II, whose name (Ashur-nasir-apli) means, “the god Ashur is the protector of the heir,” came to the Assyrian throne in 883 B.C.E. He was one of a line of energetic kings whose campaigns brought Assyria great wealth and established it as one of the Near East’s major powers.

Ashurnasirpal mounted at least fourteen military campaigns, many of which were to the north and east of Assyria. Local rulers sent the king rich presents and resources flowed into the country. This wealth was use to undertake impressive building campaigns in a new capital city created at Kalhu (modern Nimrud). Here, a citadel mound was constructed and crowned with temples and the so-called North-West Palace. Military successes led to further campaigns, this time to the west, and close links were established with states in the northern Levant. Fortresses were established on the rivers Tigris and Euphrates and staffed with garrisons.

By the time Ashurnasirpal died in 859 B.C.E., Assyria had recovered much of the territory that it had lost around 1100 B.C.E. as a result of the economic and political problems at the end of the Middle Assyrian period.

Relief panels

Later kings continued to embellish Nimrud, including Ashurnasirpal II’s son, Shalmaneser III who erected the Black Obelisk depicting the presentation of tribute from Israel.

During the eighth and seventh centuries B.C.E. Assyrian kings conquered the region from the Persian Gulf to the borders of Egypt. The most ambitious building of this period was the palace of king Sennacherib (704-681 B.C.E.) at Nineveh. The reliefs from Nineveh in the British Museum include a depiction of the siege and capture of Lachish in Judah.

The finest carvings, however, are the famous lion hunt reliefs from the North Palace at Nineveh belonging to Ashurbanipal (668-631 B.C.E.). The scenes were originally picked out with paint, which occasionally survives, and work like modern comic books, starting the story at one end and following it along the walls to the conclusion.

The Assyrians used a form of gypsum for the reliefs and carved it using iron and copper tools. The stone is easily eroded when exposed to wind and rain and when it was used outside, the reliefs are presumed to have been protected by varnish or paint. It is possible that this form of decoration was adopted by Assyrian kings following their campaigns to the west, where stone reliefs were used in Neo-Hittite cities like Carchemish. The Assyrian reliefs were part of a wider decorative scheme which also included wall paintings and glazed bricks.

The reliefs were first used extensively by king Ashurnasirpal II (about 883-859 B.CE..) at Kalhu (Nimrud). This tradition was maintained in the royal buildings in the later capital cities of Khorsabad and Nineveh.

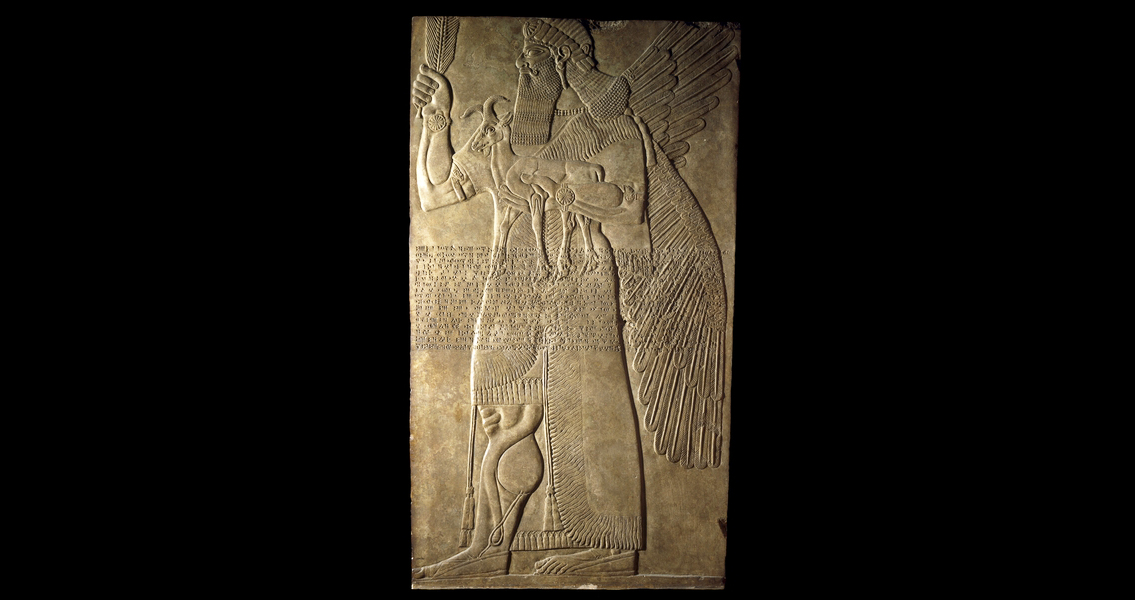

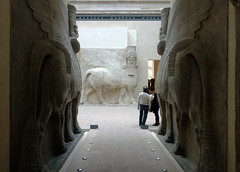

Lamassu from the citadel of Sargon II

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Winged, human-headed bulls served as guardians of the city and its palace—walking by, they almost seem to move.

These sculptures were excavated by P.-E. Botta in 1843-44.

Backstory

The lamassu in museums today (including the Louvre, shown in our video, as well the British Museum, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad, and others) came from various ancient Assyrian sites located in modern-day Iraq. They were moved to their current institutional homes by archaeologists who excavated these sites in the mid-19th century. However, many ancient Assyrian cities and palaces—and their gates, with intact lamassu figures and other sculptures—remain as important archaeological sites in their original locations in Iraq.

The Nergal gate is only one of many artifacts and sites that have been demolished or destroyed by ISIS over the past decade. Despite the existence of other examples in museums around the world, the permanent loss of these objects is a permanent loss to global cultural heritage and to the study of ancient Assyrian art and architecture.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee

Additional resources:

“Isis fighters destroy ancient artefacts at Mosul museum,” The Guardian, February 26, 2015.

P. G. Finch, “The Winged Bulls at the Nergal Gate of Nineveh,” Iraq, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Spring, 1948), pp. 9-18 (read for free online via JSTOR)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Ashurbanipal Hunting Lions

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Only the king was permitted to kill lions—and doing so signified his power and ability to keep nature at bay.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The palace decoration of Ashurbanipal

Video \(\PageIndex{14}\)

Ashurbanipal wasn’t just an Assyrian king, he was a propaganda king. The layout, decorations and even the landscaping of his palaces were all made to point to one major fact – he was more powerful than you.

Assyria vs Elam: The battle of Til Tuba

Reading Assyrian art isn’t easy — but it’s always worth it.

Video \(\PageIndex{15}\)

The battle of Til Tuba reliefs are among some of the great masterpieces of ancient Assyrian art. The movement and details are truly stunning. That said, the scenes actually being depicted are anything but easy on the eye.

Join curator Gareth Brereton as he walks you through the reliefs that once decorated the last great king of Assyria’s royal palace.

Persian

Famous for their monumental architecture, Persian kings established numerous centers in their vast empire such as Susa and Persepolis (today, in Iran).

6th century B.C.E.

Ancient Persia, an introduction

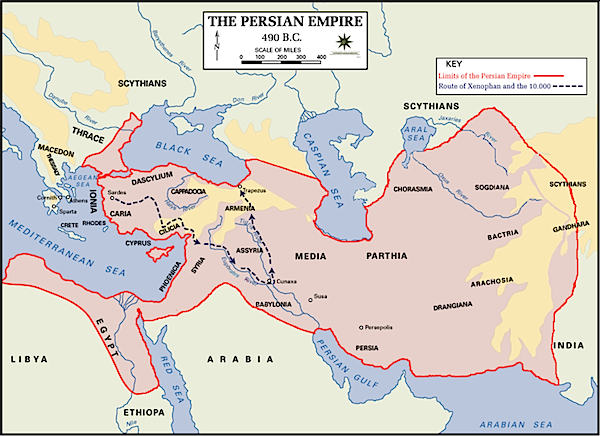

The heart of ancient Persia is in what is now southwest Iran, in the region called the Fars. In the second half of the 6th century B.C.E., the Persians (also called the Achaemenids) created an enormous empire reaching from the Indus Valley to Northern Greece and from Central Asia to Egypt.

A tolerant empire

Although the surviving literary sources on the Persian empire were written by ancient Greeks who were the sworn enemies of the Persians and highly contemptuous of them, the Persians were in fact quite tolerant and ruled a multi-ethnic empire. Persia was the first empire known to have acknowledged the different faiths, languages and political organizations of its subjects.

This tolerance for the cultures under Persian control carried over into administration. In the lands which they conquered, the Persians continued to use indigenous languages and administrative structures. For example, the Persians accepted hieroglyphic script written on papyrus in Egypt and traditional Babylonian record keeping in cuneiform in Mesopotamia. The Persians must have been very proud of this new approach to empire as can be seen in the representation of the many different peoples in the reliefs from Persepolis, a city founded by Darius the Great in the 6th century B.C.E.

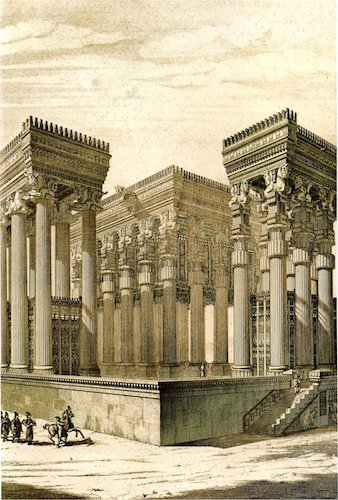

The Apadana

Persepolis included a massive columned hall used for receptions by the Kings, called the Apadana. This hall contained 72 columns and two monumental stairways.

The walls of the spaces and stairs leading up to the reception hall were carved with hundreds of figures, several of which illustrated subject peoples of various ethnicities, bringing tribute to the Persian king.

Conquered by Alexander the Great

The Persian Empire was, famously, conquered by Alexander the Great. Alexander no doubt was impressed by the Persian system of absorbing and retaining local language and traditions as he imitated this system himself in the vast lands he won in battle. Indeed, Alexander made a point of burying the last Persian emperor, Darius III, in a lavish and respectful way in the royal tombs near Persepolis. This enabled Alexander to claim title to the Persian throne and legitimize his control over the greatest empire of the Ancient Near East.

Additional resources:

Persepolis from the air (video from The Oriental Institute, University of Chicago)

The Apadana from the University of Chicago

Persepolis from the University of Chicago

The Achaemenid Persian Empire on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Timeline of Art Museum

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Figure \(\PageIndex{73}\): More Smarthistory images…

The Cyrus Cylinder and Ancient Persia

Video \(\PageIndex{16}\): The Cyrus Cylinder, after 539 B.C.E., fired clay, 21.9 cm long (video from the British Museum)

The Cyrus Cylinder is one of the most famous objects to have survived from the ancient world. It was inscribed in Babylonian cuneiform on the orders of Persian King Cyrus the Great (559-530 B.C.E.) after he captured Babylon in 539 B.C.E. It was found in Babylon in modern Iraq in 1879 during a British Museum excavation.

Cyrus claims to have achieved this with the aid of Marduk, the god of Babylon. He then describes measures of relief he brought to the inhabitants of the city, and tells how he returned a number of images of gods, which Nabonidus had collected in Babylon, to their proper temples throughout Mesopotamia and western Iran. At the same time he arranged for the restoration of these temples, and organized the return to their homelands of a number of people who had been held in Babylonia by the Babylonian kings. Although the Jews are not mentioned in this document, their return to Palestine following their deportation by Nebuchadnezzar II, was part of this policy.

The cylinder is often referred to as the first bill of human rights as it appears to encourage freedom of worship throughout the Persian Empire and to allow deported people to return to their homelands, but it in fact reflects a long tradition in Mesopotamia where, from as early as the third millennium B.C.E., kings began their reigns with declarations of reforms.

Capital of a column from the audience hall of the palace of Darius I, Susa

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

This massive capital is very different from those of Greece, and suggests the frightening power of the Persian Empire.

Video \(\PageIndex{17}\): Capital of a column from the audience hall of the palace of Darius I, Susa, c. 510 B.C.E., Achaemenid, Tell of the Apadana, Susa, Iran (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

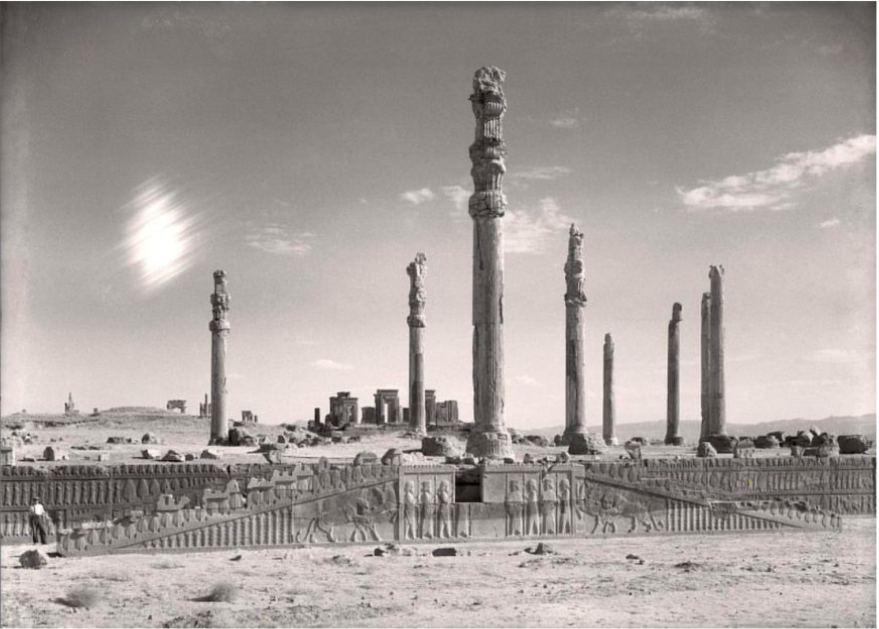

Persepolis: The Audience Hall of Darius and Xerxes

by Dr. Jeffery A. Becker

By the early fifth century B.C.E. the Achaemenid (Persian) Empire ruled an estimated 44% of the human population of planet Earth. Through regional administrators the Persian kings controlled a vast territory which they constantly sought to expand. Famous for monumental architecture, Persian kings established numerous monumental centers, among those is Persepolis (today, in Iran). The great audience hall of the Persian kings Darius and Xerxes presents a visual microcosm of the Achaemenid empire—making clear, through sculptural decoration, that the Persian king ruled over all of the subjugated ambassadors and vassals (who are shown bringing tribute in an endless eternal procession).

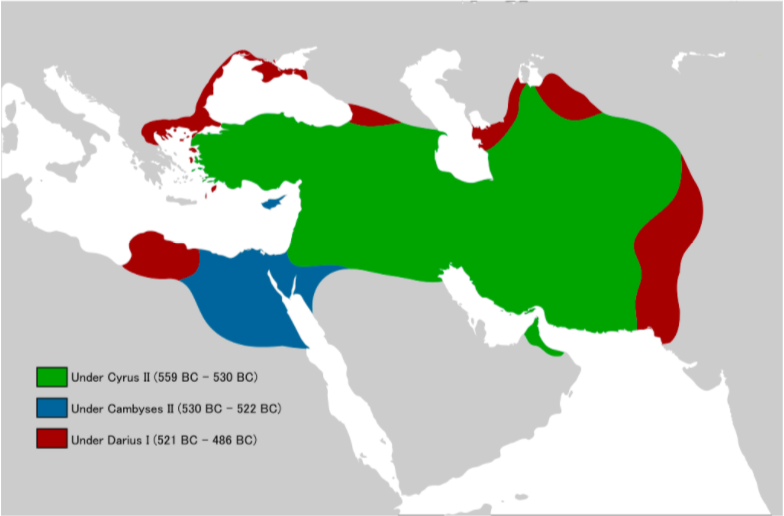

Overview of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire (First Persian Empire) was an imperial state of Western Asia founded by Cyrus the Great and flourishing from c. 550-330 B.C.E. The empire’s territory was vast, stretching from the Balkan peninsula in the west to the Indus River valley in the east. The Achaemenid Empire is notable for its strong, centralized bureaucracy that had, at its head, a king and relied upon regional satraps (regional governors).

A number of formerly independent states were made subject to the Persian Empire. These states covered a vast territory from central Asia and Afghanistan in the east to Asia Minor, Egypt, Libya, and Macedonia in the west. The Persians famously attempted to expand their empire further to include mainland Greece but they were ultimately defeated in this attempt. The Persian kings are noted for their penchant for monumental art and architecture. In creating monumental centers, including Persepolis, the Persian kings employed art and architecture to craft messages that helped to reinforce their claims to power and depict, iconographically, Persian rule.

Overview of Persepolis

Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Persian empire (c. 550-330 B.C.E.), lies some 60 km northeast of Shiraz, Iran. The earliest archaeological remains of the city date to c. 515 B.C.E. Persepolis, a Greek toponym meaning “city of the Persians”, was known to the Persians as Pārsa and was an important city of the ancient world, renowned for its monumental art and architecture. The site was excavated by German archaeologists Ernst Herzfeld, Friedrich Krefter, and Erich Schmidt between 1931 and 1939. Its remains are striking even today, leading UNESCO to register the site as a World Heritage Site in 1979.