2.1: Palmyra

- Page ID

- 63855

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Palmyra

Described as a noble city, this oasis was renowned for its rich soil and pleasant streams. Ancient Palmyra was an important stop for caravans traversing the Syrian Desert.

c. 1800 B.C.E. - 272 C.E.

Palmyra: the modern destruction of an ancient city

by DR. SALAM AL KUNTAR and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Terrorists overran Palmyra twice despite international cries for protection, sowing irreversible destruction.

Cite this page as: Dr. Salam Al Kuntar and Dr. Steven Zucker, "Palmyra: the modern destruction of an ancient city," in Smarthistory, January 5, 2018, accessed August 5, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/palmyra-destruction-2/.

Temple of Bel, Palmyra

Drawing from Greco-Roman and Eastern architecture, this temple was one of history’s great architectural achievements.

A noble city

Described as a noble city situated in a vast expanse of sand and renowned for its rich soil and pleasant streams, the ancient city of Palmyra was a stopping point for caravans traversing the Syrian Desert (Pliny the Elder Natural History 5.88.1). There is evidence that the site has been settled by people since the early second millennium B.C.E.

Known from ancient literary records—including Assyrian texts and the Hebrew Bible—Palmyra today is known as a unique and resplendent ruined city that preserves remarkable examples of monumental, hybrid architecture that blends the canon of Graeco-Roman architecture with Near Eastern elements.

Brief history

Palmyra, originally known as Tadmor, became a prosperous city under the Seleucid kings and was eventually annexed to the Roman empire after 64 B.C.E. Under Tiberius (emperor from 14-37 C.E.) the city was incorporated into the Roman province of Syria and assumed the name Palmyra. The city received the patronage of several Roman emperors and experienced great prosperity. The city suffered under the rise of the Sassanid dynasty of Persia. After the brief, revolutionary rise of queen Zenobia, the city was sacked by the Roman emperor Aurelian in 272 C.E.

A hybrid architecture

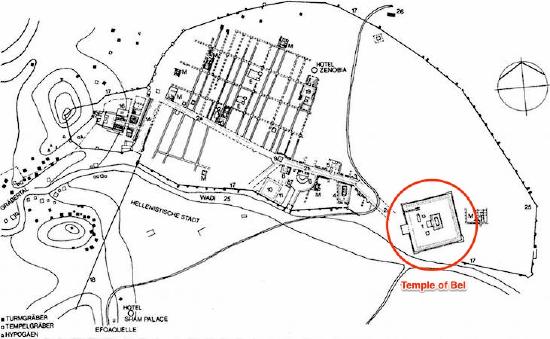

The monumental architectural remains of the city attest to its great prosperity during its heyday. Among the many surviving monuments of Palmyra is the remarkable temple of the Semitic god Bel or Baal (top of page). A discussion of its architectural features demonstrates both the plurality of artistic and architectural styles in the ancient Mediterranean, and the numerous cultures that frequently overlapped and inter-mixed there. Although an inscription attests to the temple’s dedication in 32 C.E., its completion was gradual with major architectural elements added over the course of the first and second centuries.

The organization of the temple’s ground plan derive from the traditions of eastern ritual architecture, including independent shrines for distinct divinities and, notably, the bent-axis approach to the cult (i.e. the architecture requires the celebrant to enter the temple and turn 90 degrees in order to view the offering table and cult area). The architectural elements employed in the temple’s elevation however, derive from the Graeco-Roman canon, including the use of the Corinthian order as well as various architectural elements of that adorn the frieze course and roofline. In its outward appearance, the temple seems to derive from the canon of Hellenistic Greek architecture.

The temple itself sits within a bounded, architectural precinct measuring approximately 205 meters per side. This precinct, surrounded by a portico (a colonnaded entryway), encloses the temple of Bel as well as other cult buildings. The temple itself has a very deep foundation that supports a stepped platform. At the level of the stylobate (the platform atop the steps) the area measures 55 x 30 meters and the cella (the inner chamber of the temple that held the cult statue), stands over 14 meters in height and measures 39.45 x 13.86 meters.

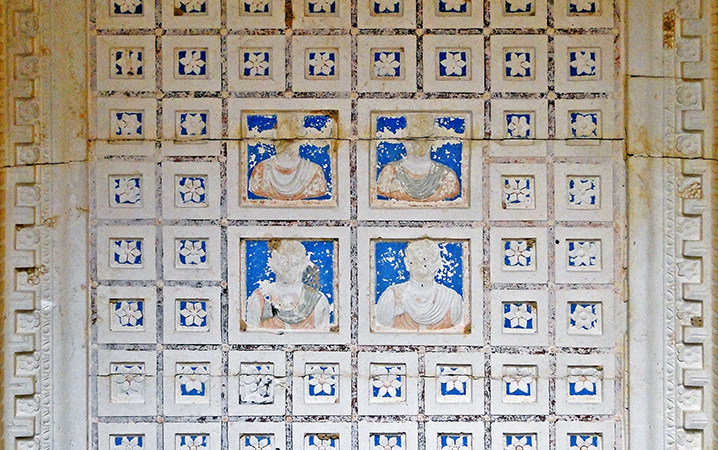

The cella is designed according to the Near Eastern tradition of the bent-axis approach and incorporates two separate shrines (thalamoi). A ramp and central stair, with an off-center doorway, grants access to the cella. The columnar arrangement is pseduoperipteral (free-standing columns at the porch with engaged columns on the sides and back) and includes an arrangement of 8 x 15 (height = 15.81 meters) fluted, Corinthian columns. The cella also has exterior Ionic half-columns at each of its ends. Merlons (crenellations) crowded the roof and the ceilings were coffered. From masons’ marks and graffiti found on the site, it seems that there were craftspeople of various background, including Greeks and Romans alongside the Palmyrenes.

The temple is dedicated to a divine triad, Bel along with the moon god Aglibol and the sun god Yarhibol. This divine triad is innovative, with the secondary gods playing the role of Bel’s attendants.

Graeco-Roman + Near Eastern

The Temple of Bel is one of the great architectural achievements of the Mediterranean world during the early first millennium. As an architectural product it draws on rich, canonical forms derived from both the Graeco-Roman and Near Eastern spheres and its technical aesthetics are of the first order. Along with temples such as that of Heliopolitan Zeus at Baalbek, the Palmyrene temple demonstrates the massive civic investment in monumental architecture.

Clearly Palmyra was prosperous, allowing its elites to invest heavily in elaborate architecture—all the same this civic investment was also central to the Mediterranean concept of urbanism where presentation architecture helped to define and advance the status of the city itself. The hybridity of the Temple of Bel further demonstrates that ancient Palmyra was a multi-cultural community and that while the cult and its function adhered to Semitic practice, the execution of the temple in the Graeco-Roman style spoke the architectural lingua franca of the expansive Roman empire.

*Note: The current political situation in Syria has resulted in the destruction numerous archaeological sites at Palmyra including the Temple of Bel.

Additional resources:

Palmyra on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Palmyra photo album on Flickr from the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World

The Divine Triad at the Louvre

Palmyra, UNESCO World Heritage Site

Pleiades Project: Palmyra, Tadmora or Hadrianopolis (Palmyra)

N. J. Andrade, Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Warwick Ball, Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire (London: Routledge, 2002).

K. Butcher, Roman Syria and the Near East (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2004).

Trevor Bryce, Ancient Syria: a Three Thousand Year History (Oxford University Press, 2014).

P. Collart and J. Vicari, Le Sanctuaire de Baalshamin à Palmyre: Topographie et architecture, 2 vols (Rome: Institut Suisse de Rome,1969).

Malcolm A. R. Colledge and Pascale Linant de Bellefonds, “Palmyra” Grove Art Online

L. Dirven, The Palmyrenes of Dura-Europos: A Study of Religious Interaction in Roman Syria (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World) (Leiden: Brill, 1999).

H. J. W. Drijvers, The Religion of Palmyra (Leiden: Brill, 1976).

Hugh Elton, Frontiers of the Roman Empire (London: Routledge, 1996).

C. F. Gates, Ancient Cities: the Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome, 2nd edition (London: Routledge, 2011).

M. Gawlikowski, Le temple palmyrénien: étude d’épigraphie et de topographie historique (Warsaw: Éditions scientifiques de Pologne, 1973).

P. Gros, L’architecture romaine: du début du iiie siècle av. J.-C. à la fin du Haut-Empire, (Paris: Picard, 1996).

Nigel Pollard, Soldiers, Cities, and Civilians in Roman Syria (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000).

H. Seyrig, R. Amy and E. Will, Le Temple de Bel à Palmyre, 2 vols (Paris: Geuthner, 1975).

A. M. Smith, II, Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

J. Starcky and M. Gawlikowski, Palmyre (Paris: Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient, 1985).

J. B. Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture (Yale: Yale University Press, 1981).

T. Wiegand et al., Palmyra: Ergebnisse der Expeditionen von 1902 und 1917 (Berlin: H. Keller, 1932).

E. Will, Les Palmyréniens: la Venise des sables: Ier siècle avant-IIIème siècle après J.-C. (Paris: A. Colin, 1992).

Palmyrene Funerary Portraiture

by STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. JEFFREY A. BECKER

At the crossroads of East and West, the caravan city of Palmyra was a melting pot of culture.

The search for identity is an unending one. As we peer across big lenses of time, such as those that separate us from the ancient Mediterranean world, one of the questions that occurs again and again is “who were these people?” In the case of Palmyra, a prosperous caravan city located in the Syrian Desert, a remarkable assemblage of funerary portraiture grants us a glimpse at the self-styled identity of a number of the city’s former occupants.

Among the tomb types from Roman Syria are the curious “tower tombs” of Palmyra, which find no comparison in Roman architecture from the western empire (above and left). They were the main tomb typology from the final quarter of the first century until the middle of the second century C.E., at which point the underground hypogeum became the preferred tomb type. A hypogeum is a subterranean tomb, most often excavated directly from the bedrock, thus creating an underground chamber or chambers for burials.

The tower tombs tend to occupy high ground and were likely built for kinship groupings. These tall, slender structures enclose tiers of niches or loculi in which human remains would be deposited. Each loculus would then be sealed with a stone slab, often carved with a relief portrait of the descendent. An exceptionally fine (and early) example is the Tower Tomb of Iamblichus (dated to 83 C.E. on the basis of epigraphic evidence—evidence from inscriptions). Another is the well preserved Tomb of Elahbel (above) with its elaborately coffered ceilings (below).

The tomb also includes a small balcony (below).

Individual portraiture

The individual loculus relief sculptures present a rich range of iconographic information about the people of Palmyra. These individualized reliefs are formatted as portrait reliefs and depict their subjects intimately, often with symbols of their status and social position.

The portrait of a priest dating c. 50-150 C.E. (above left) provides a good example of this practice. The priest holds ritual vessels (a bowl and a jug) and wears the traditional polos hat—a high, cylindrical hat worn by both men and women and derived from the divine crowns of the goddesses of the ancient Near East and Anatolia. A fragmentary female figure stands behind the priest’s right shoulder. The funerary bust of Tamma, c. 50-150 C.E. (above right) demonstrates similar traits. Tamma is richly dressed, perhaps indicating worldly wealth, and holds a spindle and distaff, perhaps indicating that she produced fabric in her household. The inscription identifies her as “Tamma, daughter of Shamshi geram, son of Malku, son of Nashum.”

The bust portrait of a couple (above) shows a pair of decedents. This portrait carries a Greek inscription, which differs from the typical Aramaic inscriptions. The text identifies the two individuals as Viria Phoebe and Gaius Virius Alcimus. This pair have the same clan name, a possible indication they are the former slaves of a brother and sister. Alcimus holds a book-roll, while the woman holds the spindle and distaff (both implements associated with cloth production). These objects may be meant to evoke their respective roles.

Group reliefs

A third century C.E. funerary relief from Palmyra now in the British Museum (below) depicts a funeral banquet. Elite tombs of this period demonstrate a mixture of Roman and Near Eastern motifs. In this particular relief that depicts a funeral banquet, the reclining male is attended by a seated female; perhaps the pair are meant to be husband and wife. The idea of the funeral banquet is a Roman motif adopted by local craftsmen. The male—presumably the deceased—reclines on a couch while holding an open vessel. He is depicted at a slightly larger scale than the attendant female. His costume is of Parthian origin, a sort of pant-suit. The Parthian empire, c. 247 B.C.E.-224 C.E. was a major political power of ancient Iran located on the eastern margin of the Roman empire. Reliefs such as this one would be arranged in groups of three in communal tombs, thereby giving the tomb chamber the resemblance of a Roman-style dining room (triclinium) in which a real banquet would have taken place.

The funerary reliefs from Palmyra form a profoundly evocative body of evidence. The individualized treatment of the sculptures themselves still serves to convey important elements about the identities of these individuals. We can glean information about wealth, social status, role in the community, familial relationships—all of which help to enrich our reconstruction of ancient Palmyrene society. The reliefs also demonstrate the degree to which Palmyra existed in a multicultural and multilingual landscape, one in which the traits, trends, styles, and languages of the Graeco-Roman world and the Near Eastern world not only overlapped but intertwined, producing new, unique cultural objects. This is an important realization, one that helps remind us of the degree to which the ancient world was diverse and varied and that a great deal of the material culture of the ancient world resulted from shared cultural influence and hybridization. The tombs of Palmyra embody and evoke this climate of cultural diversity as they still stand as monuments to Palmyrene identity.

Additional resources

W. Ball, Rome in the East: the Transformation of an Empire (London: Routledge, 2001).

M.A.R. Colledge, The Art of Palmyra (London: Westview Press, 1976).

Michael Danti, “Palmyrene Funerary Sculptures at Penn,” Expedition 43.3 (November 2001).

Palmyrene Funerary Sculptures at Penn

M. K. Heyn, “Gesture and Identity in the Funerary Art of Palmyra” American Journal of Archaeology 114.4 (October 2010) pp. 631-61. DOI: 10.3764/aja.114.4.631

Andreas J. Kropp, Images and Monuments of Near Eastern Dynasts, 100 BC – AD 100 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Lady Marti, Funerary Portrait of a Woman, Palmyra, c. AD 170-190, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen

Funerary Portrait of a Priest from Palmyra, Walters Art Museum

The Wisconsin Palmyrene Aramaic Inscription Project

Palmyra Portrait Project, AARHUS University

Portrait of a deceased woman, Liebieghaus, Frankfurt

Temple of Baalshamin, Palmyra

A hybrid of eastern and western design, this temple showcased the cultural diversity and great wealth of Palmyra.

Hybrid in design

The Temple of Baalshamin in Palmyra was a first century C.E. sanctuary dedicated to one of the key gods of the city.* As with other Palmyrene architecture, the sanctuary of Baalshamin demonstrated hybridity of design—incorporating both Near Eastern and Graeco-Roman elements.

The cult

The temple’s cult is dedicated to Baalshamin or Ba’al Šamem, a northwest Semitic divinity. The name Baalshamin is applied to various divinities at different periods in time, but most often to Hadad, also known simply as Ba’al. Along with Bel, Baalshamin was one of the two main divinities of pre-Islamic Palmyra in Syria and was a sky god. The relief plaque below depicts a votive dedication by a worshipper—Baalshamin and Bel along with Yarhibol (the lord of spring with a solar nimbus) and Aglibol (a lunar divinity).

The architecture

The temple of Baalshamin was a prostyle (having free standing columns on the façade only), tetrastyle (four columns across the façade) temple of the Corinthian order with a deep porch (visible in the photo below). What is the Corinthian Order?

The temple was set within a colonnaded precinct (a colonnade is a row of columns). The temple building dated to c. 130 C.E. and represents an addition to a sanctuary that already existed by 17 C.E.

The temple itself is conventional in its external design, meaning it conforms to what one would expect from a Classical Graeco-Roman structure. The four freestanding columns across the façade are complemented by engaged pilasters at the sides and back. What is a pilaster?

The colonnaded precinct experienced several phases of development during the first century C.E. (prior to the addition of the current temple). By the time of the temple’s construction, the colonnade had become a so-called Rhodian peristyle—meaning one flank was taller than the other three. The complex continued to develop across the course of the second century.

The temple itself adopts a Near Eastern motif of including a window in each of the cella’s flanks, a trait that is not Graeco-Roman but that finds comparison in contemporary temples in Lebanon. These windows reflect the belief that the divinity dwelled in the temple.

Context

The Temple of Baalshamin in Palmyra is a rough contemporary of the Temple of Bacchus in Baalbek (now in Lebanon). Although dissimilar in scale (the Temple of Bacchus is a monumental building), both show the contemporary propensity in Roman provincial architecture of using forecourts to frame sanctuaries, as well as showing the widespread use of the Corinthian order. This is one of a number of sanctuaries in the city that demonstrates the great wealth of the Palmyrenes. Palmyra and much of the Roman Near East was rich in cultural diversity, a diversity expressed in many ways, including by means of art and architecture.

*Note: The Temple of Baalshamin was destroyed in 2015.

Additional resources:

Palmyra Temple Was Destroyed by ISIS, U.N. Confirms—New York Times

Palmyra’s Baalshamin temple ‘blown up by IS’—BBC News

Images taken from Robert Wood’s *The Ruins of Palmyra, London, 1753

UNESCO World Heritage List: Site of Palmyra

Palmyra, UNESCO (video)

Palmyra on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Palmyra photo album on Flickr from the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World

Paul Collart, “Reconstruction Du Thalamos Du Temple De Baalshamîn a Palmyre,” Revue Archéologique, Nouvelle Série, Fasc. 2 (1970), pp. 323-327.

Klaus Schnädelbach, Topographia Palmyrena (Documents d’archéologie syrienne; 18) (Damascus, 2010).

A. M. Smith, II, Roman Palmyra: Identity, Community, and State Formation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

J. Starcky and M. Gawlikowski, Palmyre (Paris: Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient, 1985).

J. B. Ward-Perkins, Roman Imperial Architecture (Yale: Yale University Press, 1981).