11.4: North America c. 1500 - 1900 (II)

- Page ID

- 67098

British colonies and the Early Republic

Early Republic

Gilbert Stuart’s Lansdowne Portrait

A well known image

While the name Gilbert Stuart may be one unknown to most Americans, practically every American is aware of at least one of his paintings. Art historians formally call it the Athenaeum Portrait. Most everyone is familiar with it as the engraved image of George Washington that graces the front of the one-dollar bill. This is one of the dozens of portraits that Stuart painted of our first president. Another, a full-length likeness, is called the Lansdowne Portrait. Although not as famous as its bust-length counterpart, the Lansdowne Portrait retains a place of special significance within the history of American art.

Expat education

On the brink of the American Revolutionary War, Stuart decided it was time to pursue serious artistic instruction, and so, in 1775, he sailed for London and the studio of Benjamin West, whose generosity to his colonial brethren was seemingly endless.

Stuart remained in London for almost twelve years and then relocated to Ireland. He clearly had aspirations of making American versions of European Grand Manner portraits such as the likeness Hyacinthe Rigaud painted of Louis XIV in 1701. After acquiring debts sufficient to necessitate a hasty departure from the Emerald Isle, the artist told a friend about his short-term plans for Ireland and about his anticipated return to the United States:

When I can net a sum sufficient to take me to America, I shall be off to my native soil. There I expect to make a fortune by [portraits of] Washington alone. I calculate upon making a plurality of his portraits, whole lengths, what will enable me to realize; and if I should be fortunate, I will repay my English and Irish creditors. To Ireland and English I shall be adieu.

This was a task easier said than done. Stuart did not personally know the recently elected president, and the artist had been away from his homeland for 18 years.

Letter of introduction

Rather than return to Rhode Island, the state of his birth, he instead sailed for New York City, the home of John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and a close political confidant to George Washington. Stuart first met Jay in 1782 when the politician was in London negotiating the Treaty of Paris, the accord that officially ended the American Revolutionary War. Stuart arrived in New York City in early May of 1793, and a visit to Jay, one of the few people the painter could have known in Manhattan, must have been amongst Stuart’s first social calls. He painted Jay several times during the months that followed and the politician provided a letter of introduction for the relatively unknown artist to meet the president. Stuart departed New York City for Philadelphia in November 1794.

Philadephia

If painting images of George Washington was the primary reason Stuart returned to the United States, then Philadelphia was certainly the place to be. Stuart wasted little time in calling on Washington, and painted three different kinds of portraits of the president (with dozens of subsequent copies) in the years that followed. In the decades immediately preceding the invention of photography, the myriad of portraits of Washington that Stuart painted created an image Americans accepted as the portrait of their first president. The “Vaughan Type” shows Washington facing slightly to his left, the “Athenaeum Type” shows the first president facing to his right, and the “Lansdowne Type” is a full-length portrait.

Stuart painted six full-length portraits of Washington. The “Lansdowne Type” acquired its name from the owner of the first full-length portrait Stuart painted, William Petty, the first Marquis of Lansdowne. The portrait was a gift from William Bingham, a wealthy Philadelphian merchant and was intended to thank Lord Lansdowne for his financial support of the colonial cause during the American Revolutionary War.

Civilian commander

Given his European training, Stuart was well suited to execute a Grand Manner portrait of America’s first president. However, whereas previous artists such as John Trumbull and Charles Willson Peale emphasized Washington’s position as an officer in the Revolutionary Army, Stuart stressed Washington’s position as a civilian commander in chief. In the Lansdowne Portrait, Washington does not hold a scepter, wear a crown, or sit on a throne. Instead, Stuart filled the eight-foot tall composition with elements symbolic to the new republic. He wears an American made black velvet suit, one similar in fabric, cut, and color to one he frequently wore on public occasions. Washington raises his right arm in a classically inspired oratorical pose, while his left hand grasps a ceremonial sword. The President stands before a portico-like space, complete with two pairs of columns and a red curtain that has been pulled aside to reveal a background of open sky.

In addition to the architectural setting and the sitter’s pose, other elements within the composition transform the Lansdowne Portrait from a simple likeness of Washington into an official state portrait. The Neo-Classical chair on the right side of the painting contains elements from the Great Seal of the United States. A small oval medallion on the top of the chair is divided in half. The top half contains thirteen white stars in a blue field, and thirteen alternating red and white stripes appear underneath. Two erect eagles are visible on top of the leg of the table, each of which grasps a bundle of arrows, symbols of readiness for war. Underneath the table are several books, titled, General Orders, American Revolution, and Constitution & Laws of the United States that indicate Washington’s past military and political accomplishments. More books, Federalist and Journal of Congress, stand upright on top of the table. A silver inkwell, quill, and several sheets of blank paper can be seen immediately underneath Washington’s outstretched right hand.

Representing the office of the presidency

Without question, Gilbert Stuart’s Lansdowne Portrait of George Washington is far more than a portrait of the first president of the United States of America. It is instead a painting that represents not only Washington’s likeness, but also the aesthetic and political trappings of the office of the presidency and of the New Republic. Utilizing all of the traditions of European Grand Manner portraiture, it became the standard full-length political likeness of Washington throughout the Federalist period.

Additional resources:

This portrait at the National Portrait Gallery

The Landsdowne Portrait on the Google Art Project

Interactive on the painting from the Smithsonian

Information and lesson plan from Picturing America

Gilbert Stuart, The Athenaeum Portrait

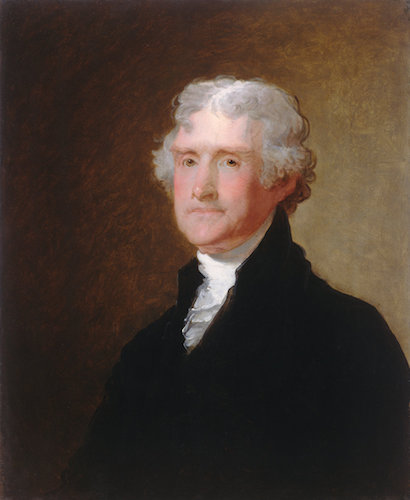

Thomas Jefferson, Monticello

A gentleman architect

In an undated note, Thomas Jefferson left clear instructions about what he wanted engraved upon his burial marker:

Here was buried

Thomas Jefferson

Author of the Declaration of American Independence

of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom

Father of the University of Virginia

Jefferson explained, “because by these, as testimonials that I have lived, I wish most to be remembered.” To be certain, there are important achievements Jefferson neglected. He was also the Governor of Virginia, American minister to France, the first Secretary of State, the third president of the United States, and one of the most accomplished gentleman architects in American history. To quote William Pierson, an architectural historian, “In spite of the fact that his training and resources were those of an amateur, he was able to perform with all the insight and boldness of a high professional.”

Indeed, even had he never entered political life, Jefferson would be remembered today as one of the earliest proponents of neoclassical architecture in the United States. Jefferson believed art was a powerful tool; it could elicit social change, could inspire the public to seek education, and could bring about a general sense of enlightenment for the American public. If Cicero believed that the goals of a skilled orator were to Teach, to Delight, and To Move, Jefferson believed that the scale and public nature of architecture could fulfill these same aspirations.

Return to the classical

Jefferson arrived at the College of William and Mary in 1760 and took an immediate interest in the architecture of the college’s campus and of Williamsburg more broadly. A lifelong book lover, Jefferson began his architectural collection while a student. His first two purchases were James Leoni’s The Architecture of A. Palladio (1715-1720) and James Gibbs’ Rules for Drawing the Several Parts of Architecture (1732).

Although never formally trained as an architect, Jefferson, both while a student and then later in life, expressed dissatisfaction with the architecture that surrounded him in Williamsburg, believing that the Wren-Baroque aesthetic common in colonial Virginia was too British for a North American audience. In an oft-quoted passage from Notes on Virginia (1782), Jefferson critically wrote of the architecture of Williamsburg:

“The College and Hospital are rude, mis-shapen piles, which, but that they have roofs, would be taken for brick-kilns. There are no other public buildings but churches and court-houses, in which no attempts are made at elegance.”

Thus, when Jefferson began to design his own home, he turned not to the architecture then in vogue around the Williamsburg area, but instead to the classically inspired architecture of Antonio Palladio and James Gibbs. Rather than place his plantation house along the bank of a river—as was the norm for Virginia’s landed gentry during the eighteenth century—Jefferson decided instead to place his home, which he named Monticello (Italian for “little mountain”) atop a solitary hill just outside Charlottesville, Virginia.

French Neo-Classicism for an American audience

Construction began in 1768 when the hilltop was first cleared and leveled, and Jefferson moved into the completed South Pavilion two years later. The early phase of Monticello’s construction was largely completed by 1771. Jefferson left both Monticello and the United States in 1784 when he accepted an appointment as America Minister to France. Over the next five years, that is, until September 1789 when Jefferson returned to the United States to serve as Secretary of State under newly elected President Washington, Jefferson had the opportunity to visit Classical and Neoclassical architecture in France.

This time abroad had an enormous effect on Jefferson’s architectural designs. The Virginia State Capitol (1785-1789) is a modified version of the Maison Carrée (16 B.C.E.), a Roman temple Jefferson saw during a visit to Nîmes, France. And although Jefferson never went so far as Rome, the influence that the Pantheon (125 C.E.) had over his Rotunda (begun 1817) at the University of Virginia is so evident it hardly need be mentioned.

Politics largely consumed Jefferson from his return to the United States until the last day of 1793 when he formally resigned from Washington’s cabinet. From this year until 1809, Jefferson diligently redesigned and rebuilt his home, creating in time one of the most recognized private homes in the history of the United States. In it, Jefferson fully integrated the ideals of French neoclassical architecture for an American audience.

In this later construction period, Jefferson fundamentally changed the proportions of Monticello. If the early construction gave the impression of a Palladian two-story pavilion, Jefferson’s later remodeling, based in part on the Hôtel de Salm (1782-87) in Paris, gives the impression of a symmetrical single-story brick home under an austere Doric entablature. The west garden façade—the view that is once again featured on the American nickel—shows Monticello’s most recognized architectural features. The two-column deep extended portico contains Doric columns that support a triangular pediment that is decorated by a semicircular window. Although the short octagonal drum and shallow dome provide Monticello a sense of verticality, the wooden balustrade that circles the roofline provides a powerful sense of horizontality. From the bottom of the building to its top, Monticello is a striking example of French Neoclassical architecture in the United States.

Jefferson changed political parties and was a Democratic-Republican by the time he was elected president. He believed the young United States needed to forge a strong diplomatic relationship with France, a country Jefferson and his political brethren believed were our revolutionary brothers in arms. With this in mind, it is unsurprising that Jefferson designed his own home after the neoclassicism then popular in France, a mode of architecture that was distinct from the style then fashionable in Great Britain. This neoclassicism—with roots in the architecture of ancient Rome—was something Jefferson was able to visit while abroad.

Buildings that speak to democratic ideals

By helping to introduce classical architecture to the United States, Jefferson intended to reinforce the ideals behind the classical past: democracy, education, rationality, civic responsibility. Because he detested the English, Jefferson continually rejected British architectural precedents for those from France. In doing so, Jefferson reinforced the symbolic nature of architecture. Jefferson did not just design a building; he designed a building that eloquently spoke to the democratic ideals of the United States. This is clearly seen in the Virginia State Capitol, in the Rotunda at the University of Virginia, and especially in his own home, Monticello.

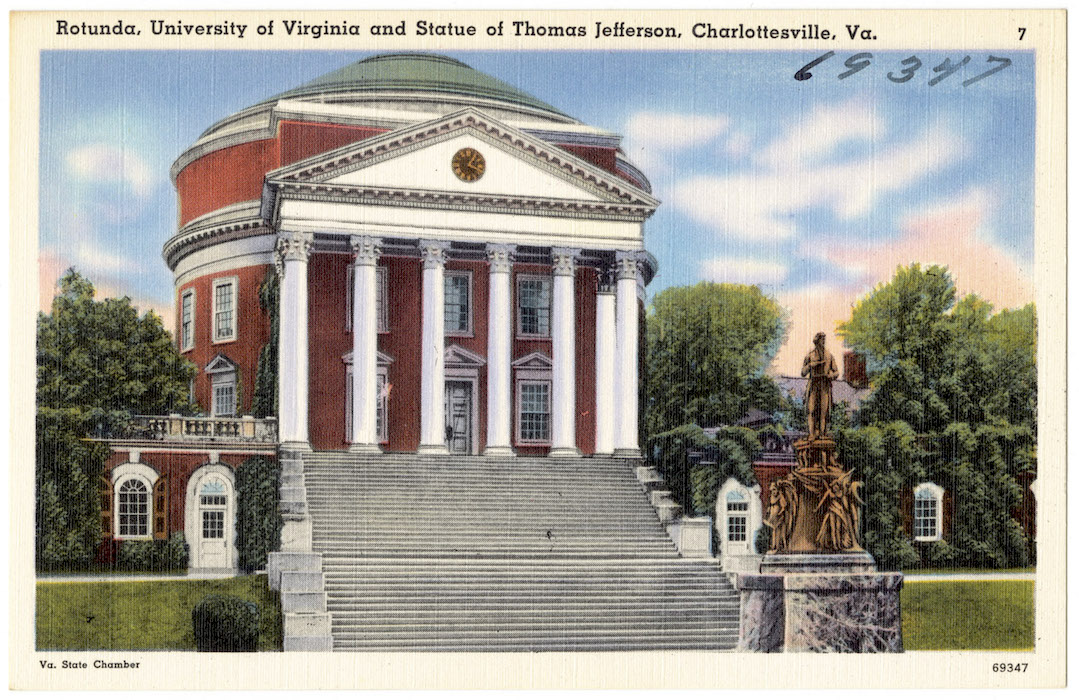

Thomas Jefferson, Rotunda, University of Virginia

A joke with a kernel of truth

The College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia is the second oldest university in the United States and was founded in 1693 (only Harvard, founded in 1636, is older). There is a longstanding joke amongst graduates of this institution:

Question: Why did Thomas Jefferson found the University of Virginia?

Answer: His kids could not get into the College of William & Mary.

To be fair, there is some truth to this joke, and then again, there is some misdirection. Thomas Jefferson did, in fact, found the University of Virginia—an achievement of which he was so proud that it is mentioned on his tombstone (whereas he omitted the fact that he was the third president of the United States). But the other part of the joke—that his children could not have been admitted to his alma mater—is a bit misleading. Jefferson’s wife, Martha Wayles, died in 1782. During their ten years of marriage, she bore him six children, only two of whom lived to adulthood. Both of these were women, and as the College of William & Mary did not formally admit female students until 1918, it would have been impossible for Jefferson’s children (those who survived and were legitimate, at least) to enroll in the institution that had educated their father.

American universities have traditionally begun with a single building and then expanded over time. This was the case of the College of William & Mary; the so-called Wren Building (above) is the oldest surviving university building in the United States. Although originally called simply “The College” or “The Main Building,” it has subsequently come to be named after Sir Christopher Wren, the English baroque architect. In fact, Hugh Jones, the college’s first professor of mathematics wrote in 1722 that Wren himself was the architect: “the building is beautiful and commodious, being first modeled by Sir Christopher Wren…” However, architectural historians do not currently believe that the most accomplished architect in the English-speaking world at the end of the seventeenth century would have made time to design a building on the very fringes of the British Empire.

A preference for the French (over the English)

Although it is unlikely that Wren designed this building at William and Mary College, there can be no doubt that whoever did was strongly influenced by Wren’s Royal Hospital at Chelsea (above). Both buildings have architectural elements that are indicative of late Renaissance and Baroque architecture in England. Both are horizontal in nature with a central pediment and cupola. Moreover, they share a similar fenestration (window) arrangement, and nearly identical dormer windows (windows that project from a sloping roof). For Thomas Jefferson, the Wren Building at the College of William & Mary was a prototype example of English architecture.

And if the political history of the United States tell us anything, it is that Thomas Jefferson did not much care for the English. This is but one of the reasons why his own architectural projects—notably his ancestral home at Monticello and the Virginia State Capitol (left)—were inspired not by English architectural antecedents, but instead by buildings from the classical past. Indeed, the Virginal State Capitol looks much like the Maison Carrée in Nîmes (France), an ancient Roman building Jefferson saw while serving as the American ambassador to France. His own home has a variety of classical (and neoclassical) architectural influences. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the neoclassical style was strongly linked with France—and Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican and strident Francophile, therefore approved.

University of Virginia: an “academical village”

At the conclusion of his political career, Jefferson turned his considerable energies towards two related enterprises: the founding of a university for the state of Virginia, and designing buildings for that institution. Jefferson very much believed in the crucial importance of education. Although an oft-repeated quotation—“An educated citizenry is a vital requisite for our survival as a free people.”—never seems to have come from his pen, it very much encapsulates Jefferson’s views on education. When he set in planning the University of Virginia—an institution founded in 1819 and began to instruct its first class in March 1825—he did so in a revolutionary way. Rather than begin as a single building and expand as needed, Jefferson envisioned—to use his phrase—an entire “academical village” where students and professor lived and learn side by side.

Jefferson designed the initial phase of the university on a symmetrical north-south axis. The longitudinal axes on the east and west sides contain pavilions for the professors, dormitories for the students, and expansive lawns. Indeed, the word “campus”—a word so commonly used to describe the grounds and buildings of a college or university—comes from the Latin word that means field. In this way, what Jefferson designed was one of the first true college campuses, complete with buildings and intentional exterior spaces.

The Rotunda (and the Pantheon)

The crowing architectural achievement of the “academical village” at the University of Virginia can be seen at the north end of the campus. Called the Rotunda, it should look immediately familiar to anyone with even a passing knowledge of Western architecture, as Jefferson designed it as a half-sized version of the ancient Roman Pantheon (below). A religious building devoted to all the Roman gods, the Pantheon demonstrates the ways in which Roman architects could take a Classical Greek idea—note the Greek temple front—and combine it with elements that were so spectacularly new that it made the Pantheon architecturally unique for nearly two millennia. Indeed, that uniqueness derives from the innovative “dome on a drum” construction that is so neatly hidden—when viewed from its ideal angle—by the Greek temple front that Roman architects so admired. Moreover, this dome, which opens into a vast interior space crowned by a singular window (or oculus) was made possible through a particularly Roman invention: concrete.

Yet Jefferson knew that his Rotunda was going to serve a different function than the building on which it was based. So, although these two buildings (The Pantheon in Rome and the Rotunda at the University of Virginia) look strikingly similar if you merely look at the architectural forms, they become quite different if one moves beyond initial appearance. Whereas the Pantheon is a religious building—a temple for all the Roman gods when it was created (and subsequently a Catholic church when it was consecrated in 609), Jefferson’s Rotunda has a strictly secular nature. As a member of the Enlightenment, Jefferson’s religious views leaned towards Deism, a belief system that generally acknowledged a Divine Maker, but rejected a belief in revelation. In fact, one of the reasons why Jefferson was keen on founding the University of Virginia was to provide his home state with a secular educational option to the religiously-oriented College of William & Mary. The materials were clearly different as well. While the expansive interior space of the Pantheon was made possible through the perfection of poured concrete, Jefferson used the wood and brick that was so indicative of mid-Atlantic architecture of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Two final differences involve the plans of the building on the ways in which light works. Whereas the Pantheon is essentially one enclosed space that is illuminated by only two sources—the oculus at the peak of the dome and the door at the building’s entrance—Jefferson’s Rotunda is a multistoried building that is illuminated by windows that circle the drum of the dome.

One might wonder why an architect in nineteenth-century America would model a library after an ancient Roman temple. But Neoclassical architecture surrounds us to this day (Neoclassical means “new classicism”—this is a style that developed in Europe at the end of the 18th century). Government buildings, colleges and universities, libraries, museums, and banks have all frequently used the architecture of the classical past as a way of giving the establishments they represent a sense of gravitas. In utilizing classical (ancient Greek and Roman) architectural forms for his library, Jefferson was expressing his admiration of the ideas set forth from the classical past: democracy, learning, and permanence. And, to make it more emphatic, the Rotunda was far removed from anything that could be considered British.

Influence

Thomas Jefferson’s resume is unmatched in the history of American politics. He was the third president of the United States (1801-09), the second vice president of the United States (1797-1801), and the first Secretary of State of the United States (1790-93). He served as the Minister to France (1785-89), a Delegate to the Congress of the Confederation (1783-84), as the governor of Virginia (1779-81), and Delegate to the Continental Congress (1775-1776). He also wrote the State of Virginia’s A Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom (1777) and was the primary author of what many believe to be one of the most perfect political documents ever written, The Declaration of Independence (1776). And yet, had Jefferson been and written none of these things, he would still be remembered today as one of the most influential architects in the history of the United States. In many ways, the Rotunda is the cardinal architectural achievement on what Jefferson thought was one of his most profound accomplishments, the founding of the University of Virginia.

Charles Willson Peale, Staircase Group (Portrait of Raphaelle Peale and Titian Ramsay Peale I)

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Charles Willson Peale, Staircase Group (Portrait of Raphaelle Peale and Titian Ramsay Peale), 1795, oil on canvas, 89-1/2 x 39-3/8 inches / 227.3 x 100 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Charles Willson Peale, The Artist in His Museum

Saddle maker, officer, artist, museum founder

He began as a saddle maker, taught dancing lessons in Colonial America, completed mezzotints in London, and served as an officer in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He also became one of the most prolific artists of his era. Yet despite this background, the name Charles Willson Peale is not one immediately familiar to those outside the circles of American art history. However, it would be difficult to overstate his artistic prominence in the United States during the decades surrounding the turn of the nineteenth century. Without doubt, Peale rests in the pantheon of American portraitists. He painted the social, political, and economic elite of his day: these sitters included scientists, presidents, and prominent merchants.

Even had he never picked up a paintbrush, Peale would be remembered today for founding the first museum of natural history in the United States. This museum officially opened on 18 July 1786, and collecting, classifying, and exhibiting objects occupied nearly the entire Peale family for many a decade to follow. Without doubt, art and nature were Charles Willson Peale’s great passions in life. Peale went so far as to name children after prominent artists and famous scientists. These names include Raphaelle, Rembrandt, Rubens, Titian, Angelica Kauffmann, Linnaeus, and Franklin.

The age of Enlightenment

For Peale and other Enlightenment-era thinkers, the human mind was able to both learn and understand the world around them through observation of the natural world. In many ways, this approach was antithetical to the religious views of the day that asked followers to accept facts on faith rather than verifiable proof. Enlightenment thinkers often attempted to explain the world in a way that removed the word “God” from the equation (or, at the very least, in a way that reduced the Divine Almighty’s direct role).

One example should suffice. For millennia, the appearance of a comet in the night sky—something both easily noticeable in the pre-streetlight world and something of uncommon occurrence—was cause for great concern and wonderment, and people often had a variety of explanations for these celestial events. For example, in 1378, a comet appeared at the moment a great pestilence swept through Germany. That same year, the Great Schism ripped the Roman Catholic Church in two, creating a papacy in Avignon, France in addition to the one at St. Peter’s in Rome. The appearance of this unknown object in the nighttime sky was seen as an indication that God was not happy, and the disastrous events that followed reaffirmed this belief.

Interestingly, 312 years earlier, a similar object appeared in the nighttime sky. The year was 1066, a date in history that is most well known for the year when William the Conqueror of Normandy crossed the English Channel and successfully seized the English throne. To commemorate his great victory, William commissioned the great Bayeux Tapestry, a 230-foot-long embroidered cloth that chronicled his army’s campaign.

One of the more famous scenes from this immense work of art shows a comet flying overhead of the soon-to-be deposed King Harold (image left). The Latin inscription above the six men who point heavenward reads, “They find the star.” This star means bad news for Harold, but, more importantly, it means good news—and a kind of Divine favor—for William.

Science tells us now that this was no star. Moreover, it was not a sign that God was angry (pestilence upon you!), or that God was happy (I would be pleased if you were to sail across the English Channel and take over the English throne!). Instead, this was the same hunk of cosmic ice that returned to Earth every 76 years (give or take). We call it Halley’s Comet after Sir Edmund Halley, the man who correctly predicted its return. Rather than believe the comet was a sign of divine approval or reproach, Halley instead applied the celestial mechanics of another Enlightenment thinker, Sir Isaac Newton, to predict the comet’s reappearance. Alas, Halley died in 1742 and the comet that would be named for him did not make its way back to Earth until 1759.

The Artist in his Museum

Although a three-paragraph digression, it is through this lens that we must consider Charles Willson Peale’s most famous—and some might suggest, his most ambitious—work, The Artist in His Museum. Painted towards the end of his life—Peale turned 81 years old the year it was completed—this monumental canvas is a kind of life story for the artist, and identifies him not only as the artist who made the painting, but, as importantly, the scientist who founded the museum that bears his name. Like most artist’s self portraits, this likeness speaks for what Peale believes was important about himself and what was important about his life’s work.

Peale stands in the foreground, smartly dressed in a black velvet suit and white cravat. A dusting of powder from his hair—he does not wear a wig—can be seen on his left shoulder. He alertly stares at the viewer and with his right arm he lifts up the red Grand Manner drapery to reveal the museum behind him. What was the “Grand Manner”?

With his left hand he seemingly gestures to the objects in the foreground. These objects tell us much about Peale himself. They include a stuffed turkey—which Benjamin Franklin believed should be the national bird of the United States—and the taxidermist tools used to preserve it. Atop the table on the right side of the painting rests a painter’s palette and several paintbrushes. Large fossilized bones from a mastodon (a jawbone, and a femur, perhaps) can also be seen on the right side. These objects—stuffed bird, painting tools, and excavated mastodon—serve as a kind of visual representation of Peale himself.

The room behind Peale is no ordinary room in Philadelphia. It is, in fact, the famous Long Room of what we now call Independence Hall, and it is filled with elements that announce Peale’s commitment to the Enlightenment. The left hand wall and that in the back of the room are filled with stuffed birds that Peale has organized according to the Linnaean classification system. Portraits of eminent men—many of whom were Peale’s friends and correspondents—can be seen near the ceiling. Clearly, this natural history museum provides an opportunity for learning about nature. A top-hat wearing gentleman walks with his young son and gestures to a display in front of them. Another man stands towards the back of the room with crossed arms and thoughtfully examines a specimen.

The fifth person in this painting—a woman who wears a dress and a Quaker bonnet—stands in the left middle ground. She faces the right side of the painting and her facial expression and gesture reveal a sense of wonderment. What has caught her amazement is not immediately apparent, as Peale has concealed it behind the curtain. On closer inspection, however, it is clear that in the middle of the room is the mastodon skeleton Peale and his family excavated and reconstructed earlier in the nineteenth century. Her reaction indicates that nature can not only teach, it can also provide awe.

There is no doubt that Peale was an artist, but he believed that his artistic endeavors were only one part of his long professional life. His The Artist in His Museum, painted near the end of his life, is a kind of visual epitaph for his life. The Baroque architect Sir Christopher Wren is buried in St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, his most famous project. His epitaph reads, “Si monumentum requires, circumspice”—If you seek his monument, look around. The same is true of Peale’s most famous painting. At the end of his life, he used this painting to announce his position as portraitist, naturalist, museum curator, and an important member of the American Enlightenment. It is, in a fashion, a monument not only to the man, but to an outlook that was shaped by the Enlightenment.

John Vanderlyn, Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos

An unusual training for an American

John Vanderlyn is different from most of his American-art peers.

For more than forty years, nearly every American who aspired to be an artist sailed eastward across the Atlantic Ocean to study in the London studio of the Pennsylvania-born painter Benjamin West. Indeed, the artists who West either taught or professionally advised comprises a ‘who’s who’ of colonial and early Federal art, and includes famous names such as John Singleton Copley, Charles Willson Peale, Gilbert Stuart, John Trumbull, and Thomas Sully. The reason for this need for transatlantic travel was simple; whereas London had the Royal Academy of Art and Paris had the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, North America had little other than a few undistinguished art academies and even fewer public collections of art. Aspiring artist had to go where the art and artist were. For those from North America, that had meant London.

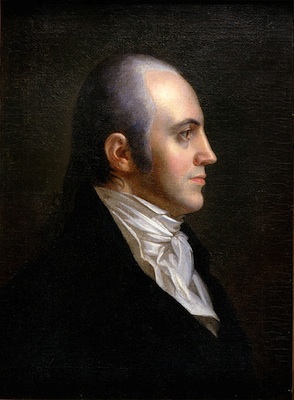

But Vanderlyn did not go to London to search out West’s advice or instruction. While a teenager, Vanderlyn moved from his home in Kingston, New York to New York City, and then later studied with Gilbert Stuart, the portraitist, who had recently returned to American shores after 18 years in London and Dublin. Stuart provided art lessons and allowed his pupil to copy portraits.

One such image Vanderlyn copied was Stuart’s portrait of Aaron Burr, New York’s Democratic-Republican Senator (and later Vice President under Thomas Jefferson).

This brought the younger artist to the attention of the ambitious politician, and Vanderlyn became a kind of protégé to Burr, living for a spell of time in his residence just outside New York City, Richmond Hill.

There can be no doubt that Stuart would have encouraged Vanderlyn to study with his former teacher, Benjamin West. When considering Burr’s strong anti-English and Francophile sentiments, however, he instead paid for Vanderlyn to study and train in Paris, thus breaking West’s near monopoly in the instruction of American artists.

Paris and Neo-Classicism

When in Paris, Vanderlyn was the first American to study at the Académie de Peinture at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and studied with François-André Vincent, a winner of the prestigious Prix de Rome and somewhat of an artistic rival to the more famous Jacques-Louis David. In doing so and over time, Vanderlyn fully embraced and absorbed the Neo-Classical style that was then flourishing on the continent.

No painting better demonstrates Vanderlyn’s commitment to French Neo-Classicism in regards to form and content better than his masterwork Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos.

Ariadne abandoned

Painted in Paris and shown at the 1812 annual Salon (the name of the official exhibitions), Vanderlyn depicts a narrative from the classical past. Princess Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos of Crete, assisted Theseus in slaying the Minotaur that lived under the palace. As a reward for his victory, Ariadne and Theseus eloped and sailed for Athens, Theseus’s home. After a sexual encounter on the island of Naxos, Theseus abandoned his new bride. Lest we feel sorry for her, she is later rescued by Dionysius who marries her and places her crown in the heavens as the constellation Corona Borealis.

The moment Vanderlyn depicted in his monumental canvas was the point when Theseus was reaching his boat to make his getaway. Ariadne, nude, and in what appears to be a post-coital slumber, lies upon a red drapery, her arms raised to her head. In a painting largely filled with muted earth tones, this red blanket gathers the visual attention of the viewer. A white sheet wraps around upper thigh. It both conceals and at the same time brings attention to her nudity.

Her body—which Vanderlyn has painted a pale milky-white value—contrasts with the North American-like landscape in which she reclines. In the right middle ground one can see the minutely painted boat Theseus boards in order to abandon Ariadne.

Neo-Classicism

Certainly, this image depicts a narrative taken from the classical past, and as such, it fits well under the broad umbrella of Neo-Classicism in regards to subject. However, it is also Neo-Classical in form when compared to the romantic works painted about at about the same time.

Indeed, one need only compare Ariadne with, for example, Goya’s The Third of May, 1808 (1814), painted just two years later, to appreciate the differences between these two different styles. Whereas Vanderlyn’s composition is linear, concise, and has a somewhat muted palette, Goya’s painting is painterly, loosely composed, with an energetic use of color.

Vanderlyn’s composition was favorably received when he exhibited it in Paris. This can be partially explained by the still popular Neo-Classical style and the ways in which it referenced back to the great reclining nudes of the Renaissance—Titian’s famous Venus of Urbino, is but one example. Moreover, Vanderlyn’s painting also anticipates many famous examples that would come later in the nineteenth century.

Indeed, one can see echoes of Vanderlyn’s Ariadne in many paintings to follow. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ Grande Odalisque (1814), Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) and Alexandre Cabanel’s Birth of Venus (1863) are but three well-known examples. Clearly, the Old World had an appetite for paintings of the reclining female nude.

An unpopular image at home

But the audience in Europe was very different from the one Vanderlyn found when he returned to New York to exhibit Ariadne in the United States. Although he had found encouragement in Paris, the more puritanical mindset of his home country combined with the lack of tradition of the female nude in American art made this an unpopular image. Vanderlyn had hoped to return to the United States and paint large-scale neoclassical history paintings. Instead, he placed his Neo-Classical efforts into portrait painting, a genre he had hoped to avoid (in the hierarchy of subject matter determined by the academies, portrait painting ranked lower than history paintings). He died at the age of 76 in near poverty. It was not until after his death that his French training or his Neo-Classical style were recognized as being key contributions to the very beginnings of art in the United States.

Thomas Birch, Perry’s Victory on Lake Erie

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Thomas Birch, Perry’s Victory on Lake Erie, c. 1814, oil on canvas, 167.64 x 245.11 cm (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts), a Seeing America video speakers: Dr. Anna O. Marley, Curator of Historical American Art, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Dr. Steven Zucker

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Thomas Birch, Fairmount Water Works

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Thomas Birch, Fairmount Water Works, 1821, oil on canvas, 51.1 x 76.3 cm (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts), a Seeing America video Speakers: Dr. Anna O. Marley, Curator of Historical American Art, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional resources

The United States in the 19th century

Artists began to develop their own styles and approaches.

c. 1800 - 1900

Romanticism in the United States

Romanticism in the United States took up themes of nature and spirituality in uniquely American ways.

c. 1800 - 1860

Washington Allston, Elijah in the Desert

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Washington Allston, Elijah in the Desert, 1818, oil on canvas, 125.09 x 184.78 cm / 49 1/4 x 72 3/4 inches (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Thomas Cole, Expulsion from the Garden of Eden

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Thomas Cole, Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, 1828, oil on canvas, 100.96 x 138.43 cm (39-3/4 x 54-1/2 inches) (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Thomas Cole, The Oxbow

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Thomas Cole, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm — The Oxbow, 1836, oil on canvas, 51 1/2 x 76″ / 130.8 x 193 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City)

An American painter born in England

During the nineteenth century—an expanse of time that saw the elevation of landscape painting to a point of national pride—Thomas Cole reigned supreme as the undisputed leader of the Hudson River School of landscape painters (not an actual school, but a group of New York city-based landscape painters). It is ironic, however, that the person who most embodies the beauty and grandeur of the American wilderness during the first half of the nineteenth century was not originally from the United States, but was instead born and lived the first seventeen years of his life in Great Britain. Originally from Bolton-le-Moor in Lancashire (England), the Cole family immigrated to the United States in 1818, first settling in Philadelphia before eventually moving to Steubenville, Ohio, a locale then on the edge of wilderness of the American west.

Early years

Cole worked briefly in Ohio as an itinerant portraitist, but returned to Philadelphia in 1823 at the age of 22 to pursue art instruction that was then unavailable in Ohio. Two years later, Cole moved to New York City where he exchanged his aspirations of painting large-scale historical compositions for the more reasonable artistic goal of completing landscapes. For instruction, Cole turned to a book, William Oram’s Precepts and Observations on the Art of Colouring in Landscaping (1810), an instructional text that had a profound effect on Cole for the remainder of his artistic career.

An important ally and an influential patron

Cole found quick success in New York City. In the year of his arrival, 1825, John Trumbull, the patriarch of American portraiture and history painting, and the president of the American Academy of Design “discovered” Cole, and the older artist made it an immediate goal to promote the talented landscape painter. In the months to follow, Trumbull introduced Cole to many of the wealthy and prominent men who would become his most influential patrons in the decades to follow. One such man was Luman Reed, an affluent merchant who, in 1836, commissioned Cole to paint the five-canvas series The Course of Empire.

Landscapes imbued with a moral message

It is in this series—and in many of the paintings to follow—that Thomas Cole found the aesthetic voice to lift the genre of landscape painting to a level that approached history painting. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, great artists aspired to complete large-scale historical compositions, paintings that often had an instructive moral message. Landscape paintings, in contrast, were often though more imitative than innovative. But in The Course of Empire, Cole was able to take the American landscape and imbue it with a moral message, as was often found in history paintings. Indeed, the landscapes Cole began to paint in the 1830s were not entirely about the land. In these works, Cole used the land as a way to say something important about the United States.

The Oxbow: More than a bend in the Connecticut River

A wonderful illustration of this is Cole’s 1836 masterwork, A View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm, a painting that is generally (and mercifully) known as The Oxbow. At first glance this painting may seem to be nothing more than an interesting view of a recognizable bend in the Connecticut River. But when viewed through the lens of nineteenth-century political ideology, this painting eloquently speaks about the widely discussed topic of westward expansion.

When looking at The Oxbow, the viewer can clearly see that Cole used a diagonal line from the lower right to the upper left to divide the composition into two unequal halves. The left-hand side of the painting depicts a sublime view of the land, a perspective that elicits feelings of danger and even fear. This is enhanced by the gloomy storm clouds that seem to pummel the not-too-distant middle ground with rain. This part of the painting depicts a virginal landscape, nature created by God and untouched by man. It is wild, unruly, and untamed.

Within the construction of American landscape painting, American artists often visually represented the notion of the untamed wilderness through the “Blasted Tree, a motif Cole paints into the lower left corner. That such a formidable tree could be obliterated in such a way suggests the herculean power of Nature.

If the left side of this painting is sublime in tenor, on the right side of the composition we can observe a peaceful, pastoral landscape that humankind has subjugated to their will. The land, which was once as disorderly as that on the left side of the painting, has now been overtaken by the order and regulation of agriculture. Animals graze. Crops grow. Smoke billows from chimneys. Boats sail upon the river. What was once wild has been tamed. The thunderstorm, which threatens the left side of the painting, has left the land on the right refreshed and no worse for the wear. The sun shines brightly, filling the right side of the painting with the golden glow of a fresh afternoon.

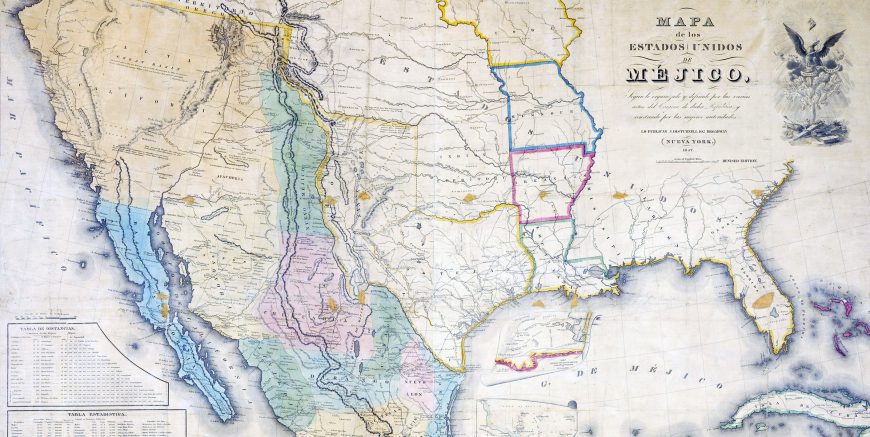

Manifest Destiny

When viewed together, the right side of the painting—the view to the east—and that of the left—the west—clearly speak to the ideology of Manifest Destiny. During the nineteenth century, discussions of westward expansion dominated political discourse. The Louisiana Purchase of 1804 essentially doubled the size of the United States, and many believed that it was a divinely ordained obligation of Americans to settle this westward territory. In The Oxbow, Cole visually shows the benefits of this process. The land to the east is ordered, productive, and useful. In contrast, the land to the west remains unbridled. Further westward expansion—a change that is destined to happen—is shown to positively alter the land.

Although Cole was the most influential landscape artist of the first half of the nineteenth century, he was not completely adverse to figure painting. Indeed, a close look at The Oxbow, reveals an easily overlooked self-portrait in the lower part of the painting. Cole wears a coat and hat and stands before a stretched canvas placed on an easel, paintbrush in hand. The artist pauses, as if in the middle of the brushstroke, to engage the viewer. This work, then, in a kind of “artist in his studio” self-portrait—is akin, in many ways, to Charles Willson Peale’s 1822 work The Artist in His Museum. In each, the artist depicts himself in his own setting. For Peale, this was his natural history museum in Philadelphia. For Cole, this was the nature he is most well known for painting.

Lasting influence

Although he only formally accepted one pupil for instruction—this was, of course, Frederic Edwin Church—Thomas Cole exerted a powerful influence on the course of landscape painting in the United States during the nineteenth century. Not content to merely paint the land, Cole elevated the landscape genre to approach the status of historical painting. The landscape painters who followed during the middle of the nineteenth century—Church, Durand, Bierstadt, and others—would often follow the trail that Cole had blazed.

Additional resources:

This painting at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cedar Grove, The Thomas Cole National Historic Site

Hudson River School on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Thomas Cole on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

On Cole’s The Course of Empire

Carl Pfluger, The Views and Visions of Thomas Cole, The Hudson River Review, vol. 47, no. 4 (Winter 1995), pp. 629-35

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Thomas Cole, The Architect’s Dream

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Thomas Cole, The Architect’s Dream, 1840, oil on canvas, 134.7 x 213.6 cm (Toledo Museum of Art)

Additional resources

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Thomas Cole, The Hunter’s Return, 1845, oil on canvas (Amon Carter Museum of American Art). Speakers: Dr. Maggie Adler, Curator, Amon Carter Museum of American Art and Dr. Beth Harris

Hicks’s The Peaceable Kingdom as Pennsylvania parable

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Edward Hicks, The Peaceable Kingdom, 1826, oil on canvas, 83.5 x 106 cm (Philadelphia Museum of Art) Speakers: Barbara Bassett, Curator of Education, School and Teacher Programs at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Beth Harris A Seeing America video

George Catlin, The White Cloud, Head Chief of the Iowas

Robed in his most splendid costume, his face gleaming with precious vermillion paint, he sits, like the prince he is, among his proud acolytes, solemnly smoking his pipe. [He is] a modern Jason.¹

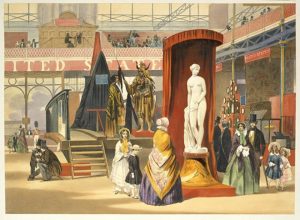

This is what the nineteenth century French novelist and critic George Sand said when she first saw this striking portrait of the head chief of the Iowas, The White Cloud, or “Mew-hu-she-kaw,” painted by the American artist, explorer, and ethnographer, George Catlin. This painting, along with a series of other portraits of American Indians by Catlin, was exhibited in the Paris Salon of 1846 (the Salon was the official exhibition of the Academy of Fine Arts in France). They stunned and titillated bourgeois Parisians with the spectacle and strangeness of the vast American wilderness and its “noble savages.”

Vanishing heroes

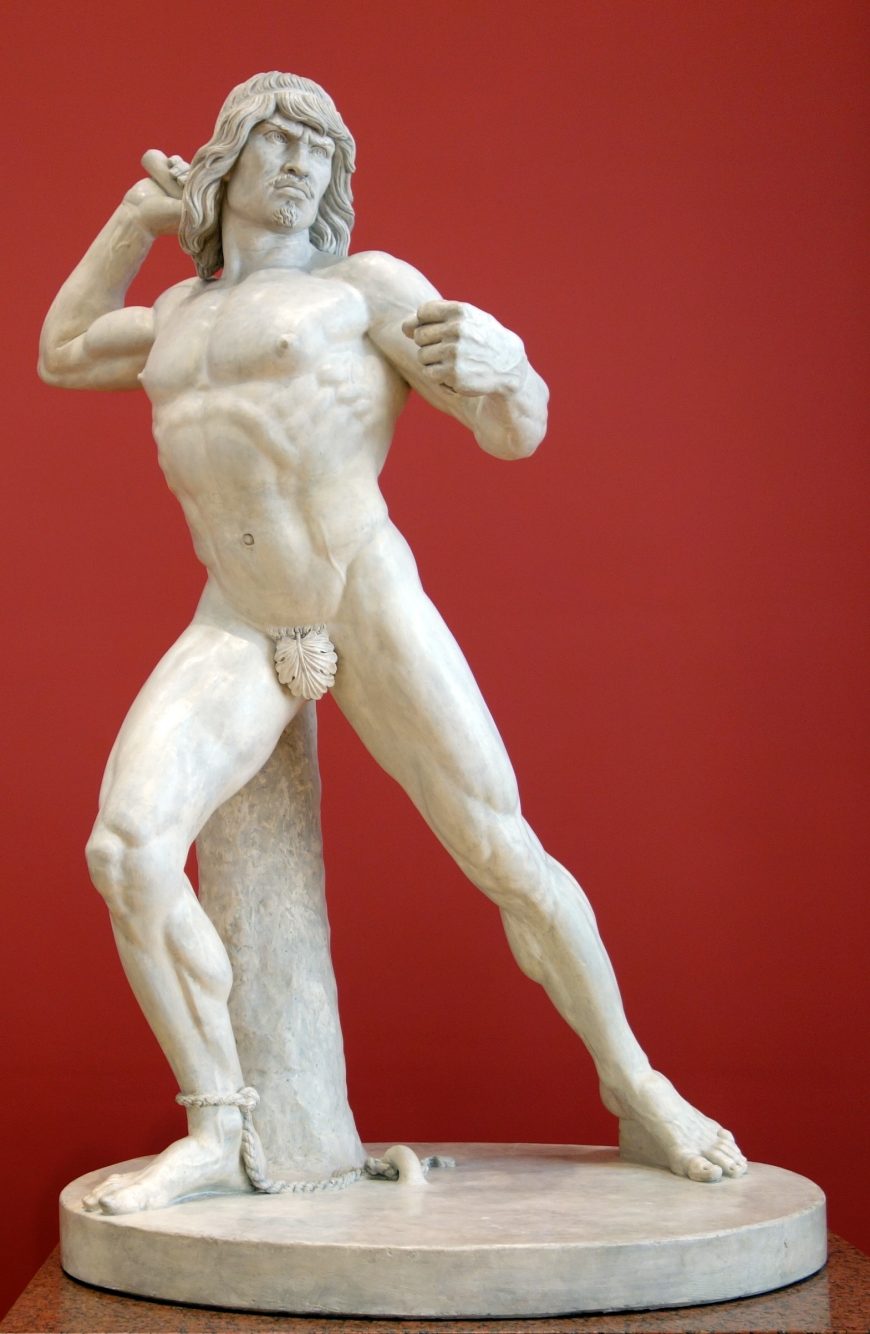

The comparison to the Greek mythological seafarer Jason is not unusual; the tendency to link the diminishing American Indian population to a vanished race of classical heroes was popular among Europeans and Americans in the nineteenth century. In 1821 the American artist Charles Bird King caused a sensation when he painted a group of Plains Indian chiefs in profile as dignified and as stately as Roman statues.

But rhapsodizing over the Indian’s innate nobility was easy to do in the face of his near extinction. By the mid-nineteenth century the popular image of the terrifying Indian who threatened Western expansion and Manifest Destiny (the widely held belief in the United States that American settlers were destined to expand throughout the continent) gave way to a more dignified, but defeated figure as the numbers of Indians across the country fell due to diseases, forced relocation, and poverty. By 1750, the American Indian population east of the Mississippi River fell by approximately 250,000 while the Caucasian and African-American population rose from around 250,000 in 1700 to nearly 1.25 million by 1750.²

Catlin painted this portrait of The White Cloud around 1844, twenty years after the Iowa tribes were forced by the U.S. government to move from Iowa to small reservations in Kansas and Nebraska. The displacement from their ancestral and spiritual homeland left the dwindling Iowa people in a fragile state. Only thirteen years before Catlin’s painting, American Indians endured one of their most traumatic collective experiences, “The Trail of Tears.” As part of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the government forced many of the southeastern tribes, the Cherokee, Seminole, Choctaw, and Chickasaw, to leave their homes and move west to designated Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. Hundreds of thousands died along the grueling journey from disease, exposure, and starvation.

A dignified portrayal

Catlin met The White Cloud, not in the U.S., but in Victorian London, when the Indian chief and his family were touring Europe as part of P.T. Barnum’s traveling circus from 1843 to 1845. The dancing Indians were a featured act in Barnum’s “Greatest Show on Earth” which showcased what Barnum believed to be rare cultural curiosities from all over the world.

By 1844, George Catlin was already something of a celebrity in America and in Europe with his Indian portraits. Catlin exaggerated his rustic backwoods character by occasionally wearing fur and moccasins to entrance his eager European audience who were hungry for an undiluted taste of the American wilderness (Catlin had grown up in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania).

The exotic plumage of traditional Indian dress appealed to Catlin at a fundamental level. It connected him to another culture and to the roots of American identity and the land.

In his journals he describes their beauty in detail:

I love the Indians for their dignity, which is natural and noble. Vanity is the same all the world over. Good looks in portraiture and fashions, whatever they are—crinoline of the lip or crinoline of the waist (and one is as beautiful and reasonable as the other), or rings in the nose or rings in the ears, they are all the same.³

However, Catlin’s portrayal of The White Cloud, in his resplendent warrior regalia, stands in sharp contrast to the squalid way in which Barnum treated him. Indian performers during the nineteenth century, whether they were with Buffalo Bill’s “Wild West Show” or P.T. Barnum’s circus, were by and large cruelly exploited. In an 1843 letter to the collector and cultural historian Moses Kimball, founder of the Boston Museum, Barnum writes of the challenges of including Indians in his act while denigrating them:

Dear Moses:

The Indians arrived and danced [last] night…They dance very well but do not [look] so fine as those last winter. They rowed, or rather paddled, another [race] last Saturday at Camden. I hired them out for the occasion for $100 and their board.

You must either get a [building] near the museum for the Indians to sleep and cook their own victuals [in] or else let them sleep in the museum on their skins & have victuals sent them from Sweeny shop. I boil up ham & potatoes, corn, beef, &c. at home& send them at each meal. The interpreter is a kind of half-breed and a decent chap; he must have common private board. The lazy devils want to be lying down nearly all the time, and as it looks so bad for them to be lying about the Museum, I have them stretched out in the workshop all day, some of them occasionally strolling about the Museum. D—n Indians anyhow. They are a lazy, shiftless set of brutes—though they will draw [in a crowd].

B.4

Barnum’s view of the Indians in his employ is the opposite of Catlin’s portrayal of The White Cloud, which brings out this man’s inherent grace and dignity.

Traditional dress

The White Cloud wears the traditional costume of the Iowa chieftain, indicative of his strengths as a warrior and hunter.

His face is painted in glowing vermillion with a green a handprint across his cheeks, a sign that he was skilled in hand-to-hand combat. He wears a headdress of two eagle feathers and deer’s tail (also dyed vermillion) and a black band across his forehead made of otter fur. His earrings are made of carved conch shells. White wolf skin covers his shoulders over his deerskin robe and he wears a necklace made of grizzly bear claws, which testifies to his superior skill as a hunter.

The necklace is the costume’s pièce de résistance, the aspect that signifies that The White Cloud is indeed the chief of his tribe. Catlin added the hazy blue sky in the background from his own imagination—the portrait was actually painted indoors in a draughty studio in London.

Catlin’s portrayal of Indian chiefs galvanized the imagination of a generation of European writers such as George Sand, Charles Baudelaire, and J.M. Barrie, whose Indians in Peter Pan are derived in part from Catlin’s portraits. Yet underneath the images of plumed warriors and braves there was a sense of underlying sadness and determination to document a vanishing way of life. “We travel to see the perishable and the perishing,” Catlin wrote in his journal in the 1830s. “To see them before they fall.”5

Catlin’s portraits today

It is difficult to look at Catlin’s The White Cloud today without overlaying our knowledge of the oppression and violence Indian peoples suffered over hundreds of years. Nevertheless, it’s important to remember that during Catlin’s time, painting was an important means that Europeans used to record and preserve the changing status of Native Americans. The cultural historian Richard Slotkin said, “Catlin tried to deal with the ephemeral quality of the wilderness—the fact that white men were destroying it as they were trying to appropriate it.”6 The Indian, to Catlin, represented a beautiful, primordial aspect of America endangered in the face of industrialization and westward expansion.

George Catlin’s paintings of the American Indians remain an enduring window onto the Old West, one of the most fascinating and contentious periods of American history. In certain aspects the art of the Old West shows us what the art historian Bryan J. Wolf calls, “the eternal last act in an imperial drama that began, as it ended, not just with territorial expansion but with cultural conquest as well.”7 Catlin’s paintings and illustrations, free of sanctimony or fabrication, show us the Indian not as a noble savage, as the European audiences often saw him, or as a demonic figure in the view of many nineteenth-century settlers, but as a real person in a real, though exotic, setting.

1. Benita Eisler, The Red Man’s Bones: George Catlin, Artist and Showman (New York: W.W. Norton, 2013), p. 328

2. Encyclopedia of American Indian History. Ed. Bruce Johansen. (ABC-CLIO, 2007), p. 115

3. George Catlin, Episodes from “Life among the Indians” and “Last Rambles,” (New York: Dover Publications: 1997), p. 251

4. Iowa Indians at the American Museum, The Lost Museum (American Social History Productions, Inc., 2002-2006)

5. George Catlin, Episodes from “Life among the Indians” and “Last Rambles,” (New York: Dover Publications: 1997) p. 73

6. Robert Hughes, American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America (New York: Knopf, 1999)

7. Bryan J. Wolf. “How the West Was Hung, Or, When I Hear the Word ‘Culture’ I Take Out My Checkbook: The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820-1920,” American Quarterly, Vol. 44, No. 3 (Sep., 1992), p. 423

Additional resources:

This painting at the National Gallery of Art

George Catlin and his Indian Gallery from the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Biography of the artist from the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Charles Bird King, Young Omahaw, War Eagle, Little Missouri, and Pawnees at the museum

Susanna Reich, Painting the Wild Frontier: The Art and Adventures of George Catlin, (New York: Clarion), p. 77

An Eye for Art: Focusing on Great Artists and Their Work. National Gallery of Art, (Chicago Review Press: 2013), p. 40

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware,1851, oil on canvas, 379 x 648 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

An American icon (made in Germany)

Washington Crossing the Delaware is one of the most recognizable images in the history of American art. You might be surprised, however, to learn that it was not painted by an American artist at work in the United States, but was instead completed by Emanuel Leutze, an artist born in Germany, and that it was painted in Düsseldorf during the middle of the nineteenth century.

Leutze painted two versions of this painting. He began the first in 1849 immediately following the failure of Germany’s own revolution. This initial canvas was eventually destroyed during an Allied bombing raid in World War II. The artist began the second version of Washington Crossing the Delaware in 1850. This later painting was transported to New York where it was exhibited in a gallery in October 1851. Two years later, Marshall O. Roberts, a wealthy capitalist, purchased the work for the then-staggering price of $10,000. It was donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1897. It remained there until 1950 when long held curatorial concerns about its bombastic, crowd-pleasing qualities led the museum to send it to Dallas and eventually to a site near the actual river crossing. The painting returned to New York in 1970.

Although Emanuel Leutze was born in Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany, his family immigrated to the United States before he turned ten years of age. His first art instruction came in 1834 when he studied drawing and portraiture with John Rubens Smith, a London-born artist who worked in the United States during the first half of the 19th Century. Wealthy Philadelphian patrons recognized Leutze’s talent and sponsored the young artist to study at the Königliche Kunstacademie in Düsseldorf. While there, Leutze came to know many American artists who were then studying in Germany. These artists included Worthington Whittredge, Albert Bierstadt, Charles Wilmar, and Eastman Johnson.

Although he was active in portraiture, Leutze’s fame today rests upon his history paintings, and among these, Washington Crossing the Delaware is the most recognizable and ambitious. It is, in one word, colossal, both in scale and patriotic zeal.

Brilliance and desperation on a vast scale

Little can prepare a viewer for the experience of standing before a painting that measures more than 12 x 21 feet. The monumental scale of the composition is matched by the importance of the historical event Leutze painted. Without doubt, Leutze took his subject from one of the turning points in the American Revolutionary War.

The Colonial cause appeared exceptionally bleak as the year 1776 came to a close. In a military move that navigated the fine line between brilliance and desperation, George Washington led the Colonial army across the Delaware River shortly after nightfall on 25 December in order to attack the Hessian encampment outside Trenton, New Jersey. Washington and his army achieved an unprecedented tactical surprise and delivered a much-needed military and moral victory. Washington’s army killed 22 Hessian soldiers, wounded 98 more, and captured more than 1,000 (Hessians were Germans soldiers hired by the British Empire). The Colonial Army had less than ten combined dead and wounded soldiers. After many military setbacks in the North, Washington’s bold move on Christmas night 1776 helped provide a sense of hope for the Colonial cause.

In addition to General Washington, Leutze has filled the boat with a variety of ‘types’ of soldiers. Washington and his two officers are distinguished by their blue coats, the trademark attire of a Continental officer.

The remaining nine men appear to be members of the militia. Three men row at the bow of the boat. One is an African American, another wears the checkerboard bonnet of a Scotsman, and the third wears a coonskin cap.

Two farmers, distinguished by their broad-brimmed hats, huddle against the frigid cold in the middle of the boat, while the man at the stern wears the moccasins, pants, and hat of a Native American. This collection of people suggests the all-inclusive nature of the Colonial cause in the American Revolutionary War.

Poetic license

Despite Leutze’s interest in history, there is little historical accuracy to be found within the painting. First, the “Stars and Stripes” flag shown in the painting was not in use until September 1777, and the size of the boat is far too small to accommodate the twelve men who occupy it.

And although this event happened in the middle of the night, Leutze shows the crossing occurring at the break of dawn. Rather than depict the Delaware River, a waterway that was rather narrow where Washington and the Continental Army crossed, Leutze paints what appears to be a river with the breadth and ice formation of the Rhine. Finally, and perhaps most interestingly, Leuzte paints Washington standing upright, an unlikely and precarious posture for anyone in a short-walled rowboat.

It is clear then that Washington Crossing the Delaware‘s strength is not in the correct rendering of an historical event. Leutze’s primary goal was to create a work of art that deliberately glorified General Washington, the Colonial-American cause, and commemorated a military action of particular significance. In doing so, Leutze created one of the most iconic images in the history of American art.

Additional resources:

This painting at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Corey Kilgannon, “Crossing the Delaware, More Accurately”, New York Times (December 2011)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Envisioning Manifest Destiny

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way (mural study for the United States Capitol building), 1861, oil on canvas, 84.5 x 110.1 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Sara Carr Upton, 1931.6.1)

Peter Frederick Rothermel, De Soto Raising the Cross on the Banks of the Mississippi

Video \(\PageIndex{12}\): Peter Frederick Rothermel, De Soto Raising the Cross on the Banks of the Mississippi, 1851, oil on canvas, 101.6 x 127 cm (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, funds provided by the Henry C. Gibson Fund and Mrs. Elliott R. Detchon, 1987.31), a Seeing America video Speakers: Dr. Anna O. Marley, Curator of Historical American Art, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Dr. Steven Zucker

Additional Resources

This painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Historic rotunda paintings, Architect of the Capitol

History of Hernando de Soto’s expedition, Chickasaw Nation

Excavation, de Soto’s cross(?), Arkansas Archaeological Survey

Frederic Edwin Church, Niagara and Heart of the Andes

A precise depiction of nature

If Thomas Cole represents the first generation of the Hudson River School of painters, then Frederic Edwin Church, the only pupil Cole ever instructed, certainly represents the generation that followed. Yet despite the teacher/student relationship that they shared, they differed in the ways in which they conceived of the American landscape. For Cole, landscape painting was a pictorial device in which to reach allegorical or narrative ends. While Church at first followed his teacher’s instruction in this regard, the younger artist set allegory and narrative aside in favor of a more focused and precise depiction of nature.

A teacher’s praise: “The finest eye of drawing in the world”

Church was born in Hartford, Connecticut, to a wealthy family; his father was a prosperous silversmith and watchmaker. Daniel Wadsworth, one of the most influential art patrons of his time and the founder of the oldest public art museum in the United States—the Wadsworth Atheneum—introduced Church to Cole in 1844. Although still but a teenager, Cole remarked that Church possessed ‘the finest eye of drawing in the world.’ Church’s immense skill is demonstrated by his election as an Associate of the National Academy of Design in May of 1844. Just barely 24 years of age, Church was the youngest artist so honored. But one year later his status was to that of Academician. Clearly, his career was off to a meteoric beginning.

Blockbuster landscapes

Today, Church is most famous for his large, blockbuster-sized landscapes. Among the many he painted, Niagara (1857) and The Heart of the Andes (1863) are justifiably the most famous. Together, these two paintings vaulted Church to the position of the most famous painter in the United States.

Although Church was not the first artist to depict the Great Falls of Niagara—John Vanderlyn, John Trumbull, and Cole had made attempts earlier in the nineteenth century—he was the first to somehow capture the roaring essence of what many then considered to be the greatest natural treasure in the United States. In contrast to earlier painters, however, Church placed the viewer close to the falls and suspends them immediately above the ledge from which the water thrillingly descends. Even the panorama-like horizontal format and the colossal size (106.5 x 229.9 cm) accentuate the sublime nature of the composition.

An American image

Even though Church depicted the Canadian side of Niagara Falls, this image became wildly popular, both in the United States and in Europe, and has, over time, become a uniquely “American” image. When completed in 1857, Church exhibited this work at a one-painting show at the New York commercial art gallery of Williams, Stevens, and Williams. Within two weeks of the exhibition’s opening, more than 100,000 visitors had paid twenty-five cents each to view Church’s masterwork. The art-loving public was clearly fascinated and enchanted by this image. Many used opera glasses to discern the minute details that were only visible upon close inspection. Church, ever the businessman, generated additional revenue through the sale of chromolithographs of the painting.

After a successful exhibit in New York, Church then toured Niagara to various cites on the east coast, and eventually even took the image to London and Paris. In all, Niagara made Church both a wealthy man and amongst the most famous of American painters.

Return to South America

If 1857 marks the year of Church completed Niagara, it also marks his return to South America, a location the artist had visited just four years prior. Cyrus Field, a wealthy New York businessman who was to become one of Church’s most reliable patrons, financed both of these adventures. Church spent more than two months in South America—most of this in Ecuador—and became keenly interested in Alexander von Humboldt, the Prussian naturalist and acclaimed author of Kosmos. This two-volume study of geology and natural history was published in Germany in 1845 and 1847. English translations followed shortly thereafter, and Humboltdt’s theories had an immense impact on Church’s views of the natural world. When the artist returned to his New York studio, he arrived with countless preparatory drawings and watercolors from which to base a monumental composition.

Not just a painting—an experience

And complete a monumental composition Church did, not only in size (168 x 302.9 cm), but also in visual scope. Church unveiled the painting at Lyrique Hall on 27 April 1859, and was moved to the Tenth Street Studio Building two days later. Like Niagara, The Heart of the Andes was more for contemporary viewers than just a painting; countless writers agreed that seeing the painting was an experience. Church placed the painting in a darkened room and dramatically illuminated it through the use of gas lamps. An enormous frame that resembled window molding only increased the painting’s visual impact. As with Niagara, the twenty-five cent ticket price for The Heart of the Andes entitled viewers to borrow a pair of opera glasses and a set of pamphlets that explained the composition through the geographical ideas von Humboldt wrote of in his Kosmos.

Praise from Mark Twain

Indeed, if Niagara was a depiction of a singular scene, The Heart of the Andes is instead a pictorial composite view of Humboldt’s theories. The public was once again smitten with Church’s efforts, and more than 12,000 visitors paid the quarter admission charge. After New York, Church sent The Heart of the Andes on tour to both domestic and foreign locations. Mark Twain saw it when it arrived in St. Louis in 1860 and wrote to this brother:

Pamela and I have just returned from a visit to the most wonderfully beautiful painting which this city has ever seen–Church’s “Heart of the Andes”–which represents a lovely valley with its rich vegetation in all the bloom and glory of a tropical summer–dotted with birds and flowers of all colors and shades of color, and sunny slopes, and shady corners, and twilight groves, and cool cascades–all grandly set off with a majestic mountain in the background with its gleaming summit clothed in everlasting ice and snow! I have seen it several times, but it is always a new picture–totally new–you seem to see nothing the second time which you saw the first. We took the opera glass, and examined its beauties minutely, for the naked eye cannot discern the little wayside flowers, and soft shadows and patches of sunshine, and half-hidden bunches of grass and jets of water which form some of its most enchanting features…You will never get tired of looking at the picture, but your reflections –your efforts to grasp an intelligible Something–you hardly know what –will grow so painful that you will have to go away from the thing, in order to obtain relief. You may find relief, but you cannot banish the picture–It remains with you still. It is in my mind now–and the smallest feature could not be removed without my detecting it.

The composition

If Church had ever read Twain’s remarks, there can be little doubt the artist would have been delighted. Church aspired to take many different components and assemble them into a cohesive and believable whole. The monumental snow-capped mountain in the deep background is Mt. Chimborazo, one of the highest peaks in South America. Moving to the foreground, Church leads the viewer through a variety of topographical zones which all contain unique flora and fauna. There is but a little human presence in this vast depiction of space.A colonial Spanish hacienda appears in the central middle ground, resting on the banks of a river. This waterway flows to the viewer’s right, eventually arriving at a waterfall—a Niagara in miniature—on the right side of the painting. A well-traveled footpath in the left foreground leads the eye to a pair of people who worship before a simple wooden cross. Beyond these ‘major’ elements, the composition is filled with minute details unobservable in any reproduction. Flowers bloom, birds flutter, water flows, and wind seems to blow.

A nineteenth-century artistic entrepreneur

Niagara and The Heart of the Andes are only two paintings from a long and productive professional career that spanned North and South America, Europe, and the Middle East. However, they stand as excellent examples of Frederic Church’s extensive oeuvre and his practices as a nineteenth-century artistic entrepreneur. Whereas Thomas Cole, Church’s artistic mentor, used the landscape as a visual tool on the path towards allegory and narrative, Church instead placed great artistic focus on exactitude and specificity in regards to flora, fauna, and geological formations. The huge size, panoramic views, and incredible detail vaulted him into the highest ranks of nineteenth century American landscapists.

Additional resources:

Church’s Niagara at the National Gallery of Art

Church’s Heart of the Andes at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Frederic Edwin Church on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

The Hudson River School on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Olana, Church’s fabulous home on the Hudson River

Frederic Edwin Church, The Iceberg

Video \(\PageIndex{13}\): Frederic Edwin Church, The Iceberg, c. 1875, oil on canvas, 55.9 x 68.6 cm (Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1993.6), a Seeing America video speakers: Dr. Peter John Brownlee, Curator, Terra Foundation for American Art and Dr. Beth Harris

Additional Resources

This painting at the Terra Foundation for American Art

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Fitz Henry Lane, Owl’s Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine

Video \(\PageIndex{14}\): Fitz Henry Lane, Owl’s Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine, 1862, oil on canvas, 40 x 66.36 cm (15-3/4 x 26-1/8 inches) (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Albert Bierstadt, Hetch Hetchy Valley, California

Video \(\PageIndex{15}\): Albert Bierstadt, Hetch Hetchy Valley, California, c. 1874-80, oil on canvas, 94.8 x 148.2 cm (Bequest of Laura M. Lyman, in memory of her husband Theodore Lyman, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)

Additional resources:

Realism in the United States

Winslow Homer and Thomas Eakins epitomized the Realist movement in the United States.

1820 - 1895

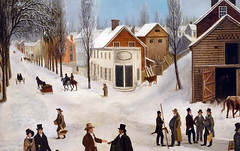

Francis Guy, Winter Scene in Brooklyn

Video \(\PageIndex{16}\): Francis Guy, Winter Scene in Brooklyn, 1820, oil on canvas, 147.3 x 260.2 cm (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art). Speakers: Dr. Margaret C. Conrads and Dr. Beth Harris.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

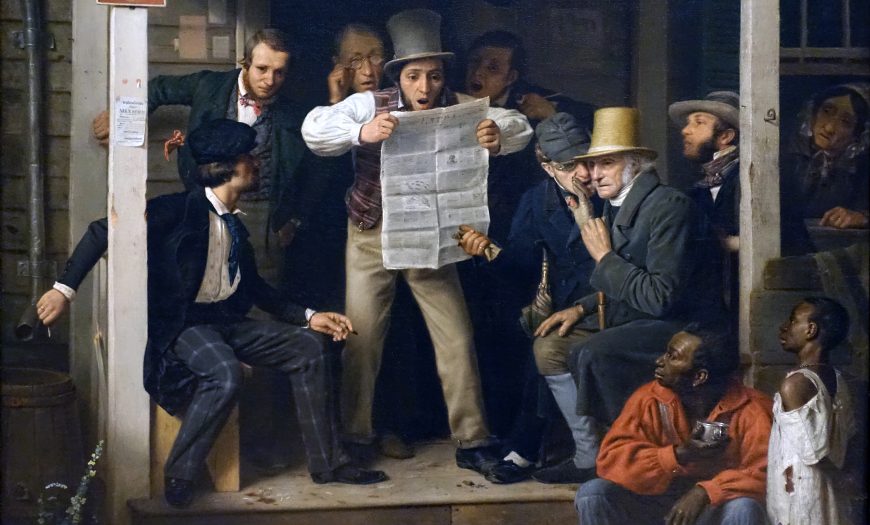

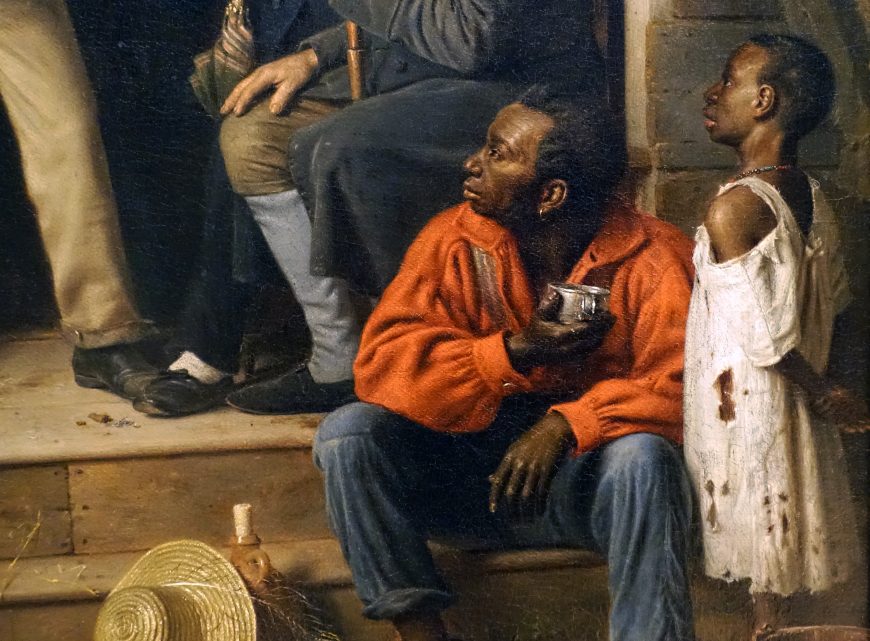

William Sidney Mount, Bargaining for a Horse

The New York painter William Sidney Mount painted this intimate, comically vibrant picture in 1835. Along with Raffling for the Goose and Eel Spearing at Setauket, Bargaining for a Horse is one of Mount’s great works and a striking example of early nineteenth-century American genre painting at its best.

Mount (and other artists like George Caleb Bingham) captured contemporary scenes of rural American life at the cusp of the country’s transition into urbanization and modernity. Mount’s childhood home in Long Island, once pastoral and sleepy in its cozy insularity, became—like many parts of America—changed by the presence of expanding railroad networks. Mount’s specialty as an artist lay in his ability to document the last remnants of the old Yankee culture of the New York countryside before the Yankee became gentrified and adjusted to the cosmopolitan demands of the nineteenth century (Yankee a refers to people from the northeast—especially those descended from colonial New England settlers).

Mount’s ambition to be a history painter

Though a renowned painter of genre scenes, William Sidney Mount had initially set out to be a history painter like Benjamin West. Mount was born into a wealthy land-owning family in Long Island in 1807. When his father died seven years later, Mount was sent to live with his uncle, Micah Hawkins, a successful wholesale grocer. At seventeen, Mount was an apprentice to his brother Henry, a sign painter. He took drawing courses at the National Academy of Design in New York, where he learned to appreciate the work of the Masters of European art and acquired an appreciation of landscapes and history painting. However, Mount’s first major work, a biblical scene, Christ Raising the Daughter of Jairus, received little critical attention when it debuted in 1828.

During the 1820s, a wide variety of landscape and genre prints circulated across the United States. Prints of rustic genre scenes by the Scottish painter David Wilkie were particularly popular with contemporary European and American audiences. Wilkie’s success convinced Mount to turn his attention to genre painting.

Bargaining for a Horse