10.7: Dada and Surrealism (II)

- Page ID

- 66958

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Surrealism

A beginner's guide

Surrealist Techniques: Subversive Realism

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

The omnipotence of the dream

A central approach of Surrealist visual art was derived from André Breton’s assertion of “the omnipotence of the dream” in the first Surrealist Manifesto. Following the ideas of Sigmund Freud, the Surrealists saw dreams as visual representations of unconscious thoughts and desires. In their first magazine, La Révolution Surréaliste, they published accounts of their own dreams and reproductions of art that seemed to record dream images, notably the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico.

In addition to the dream-like atmosphere of de Chirico’s work, the Surrealists were attracted to what are often called its literary qualities. The strange juxtaposition of female nude, bananas, and train in The Uncertainty of the Poet seems like a literal illustration of the discordant imagery of a modern poem. In addition, the erotic symbolism of the image conforms to Freud’s belief in the central importance of sexuality in the unconscious.

Rejecting the formal concerns of modern art

In claiming de Chirico’s pre-war work as exemplary, the Surrealists implicitly rejected modern art’s emphasis on formal innovation. De Chirico’s use of linear perspective, his inexpressive representation of objects, and his lack of interest in the material qualities of paint all seemed to revive the outdated naturalistic conventions of pre-modern painting, as did his use of complex, symbolic subject matter.

For the Surrealists de Chirico’s style was irrelevant; what mattered to them was his ability to represent unconscious dream images. They were interested in the subject of his painting, not how it was painted. In their willingness to elevate subject matter over painting style and technique the Surrealists explicitly placed themselves outside of what they considered were the limiting concerns of established modern art. In return, many critics (and later art historians) attacked the Surrealists for failing to understand and appreciate the formal achievements of modern art.

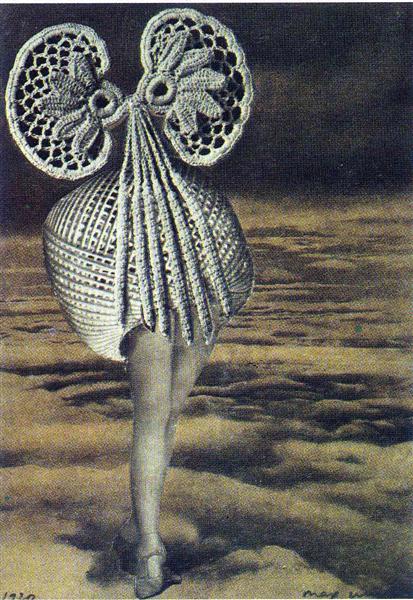

Because the movement was initiated and led by writers, Surrealist art was often considered to be literary and illustrative rather than a properly modern visual art. This overlooked the fact that many prominent Surrealist artists, including André Masson, Joan Miró, and Max Ernst, frequently employed modern styles and developed innovative artistic techniques.

For the Surrealists, an artist’s style and technique were the means to concretize inspired thinking, the creative activity of the unconscious. Whether those means were traditional naturalism or the more abstract innovations of modern art was not important as long as they were effective. The use of meticulous naturalistic techniques — traditionally employed to represent the accepted “reality” of the external world — demonstrated the equal reality of the unconscious world revealed by Surrealism.

A window into another world

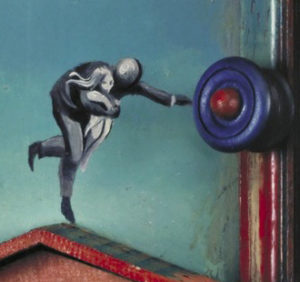

The complexity of the Surrealists’ challenge to modernist values can be appreciated by considering Max Ernst’s Two Children Threatened by a Nightingale. This painting was one of the first works by a Surrealist artist reproduced in the group’s journal, La Révolution Surréaliste. It combines echoes of de Chirico’s classical architecture and deep perspectival space with an incomprehensible nightmarish scene of violence in the foreground. Small wooden elements are attached to the painting to form a building, gate, and doorknob. The title is handwritten on the edge of the frame, which connects the painted world to the world of the viewer.

Ernst’s combination of painting, writing, collage, and relief sculpture disrupts the established categories of the individual arts as much as the image defies rational explanation. The painting is no longer simply a flat plane covered by colors, it has returned to its pre-modernist role as a window into another world, and that world is one into which we as viewers are invited. The gate on the left has swung open towards us, and the man running on the roof of the building at the right reaches for the “doorknob” on the frame that separates our world from his.

For the Surrealists who desired the complete breakdown of distinctions between art and life, dream and reality, Ernst’s disruption of pictorial boundaries meant far more than a challenge to the conventional distinctions between the different arts. It was the means to enter an entirely new world and heralded the concrete realization of Surrealism’s ultimate goal, the resolution of dream and reality into a new surreality.

The interior model

The Surrealists believed that the world of the imagination was the only proper subject for the arts, which must challenge what Breton called “the poverty of reality.” He claimed that the work of art must “refer to a purely interior model.” While this statement applies to all Surrealist artworks, regardless of productive technique, style, or subject, many Surrealist artists followed de Chirico’s example and created dreamlike imagery that appears to literally reveal the “interior model.”

Yves Tanguy’s meticulously painted depictions of imaginary landscapes stretching off to an infinitely distant horizon combine the naturalistic rendering of real space and light effects with suggestive abstract forms. Their naturalism invites the viewer’s imaginative entry into the world they make visible and presents the possibility that the world of the unconscious can be made real.

Realism as subversive

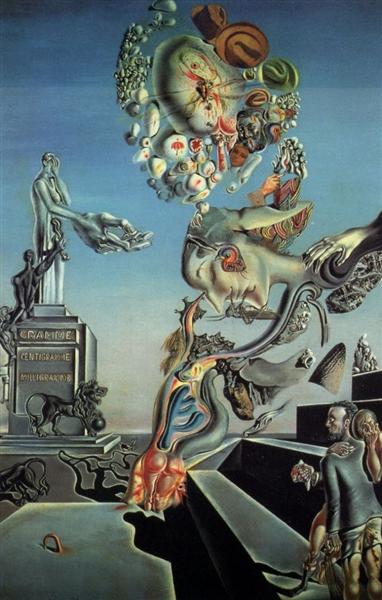

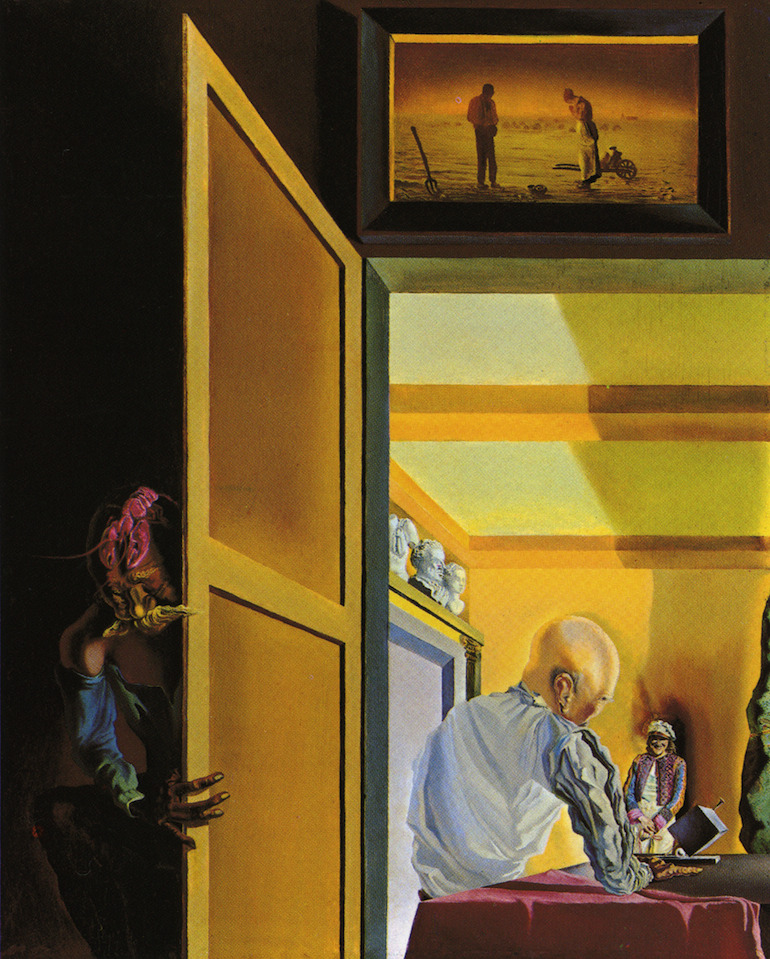

The realistic representation of the world of the unconscious reached its apogee in the paintings of Salvador Dalí, who adopted an extremely detailed realistic technique reminiscent of nineteenth-century academic painting. This was an explicit attempt to turn academic naturalism into a subversive technique.

The vivid realism of Dalí’s bizarre scenes seems to confirm that the world they represent is just as real as scenes encountered in ordinary waking life. In paintings such as The Lugubrious Game, Dalí minutely depicted his psychological obsessions, which were largely derived from Freud’s theories of infantile eroticism.

The artist’s profile floats horizontally in the center of the painting and generates a bizarre collection of objects, human figures, animals, and insects. Explicit and symbolic depictions of male and female genitalia abound, as do direct references to Freud’s theories of castration anxiety and anality. In this painting and many others Dalí portrays a universe in which the most apparently innocent objects, from a seashell to a man’s hat, acquire erotic significance.

Systematic confusion

Dalí invented a technical strategy for Surrealist art that he called “paranoia criticism.” In Dalí’s view unconscious erotic desires inevitably shape our vision of reality, and the Surrealist artist’s role is to demonstrate this in order to “systematize confusion,” overthrow rationality, and discredit what we think of as reality. Just as paranoiacs are convinced that seemingly unrelated objects and events are in fact intimately connected to their own obsessions, Dalí’s paranoiac paintings were intended to demonstrate how his imagination radically transforms objects to make them conform to his desires.

His first published paranoiac painting, The Invisible Man, depicts a strange landscape with multiple figures and objects. Individual elements also create the figure of a large seated man. The back of a nude woman in the upper center of the image is one of his upper arms. His face appears in a collection of architectural elements, and his hair is also clouds. The longer you look at the painting, the more figures and parts of figures you will see. Paintings such as this were intended to make viewers aware that the “reality” they see is only one view. It is possible to make reality answer our desires simply by changing the way we look at things.

Philosophical conundrums

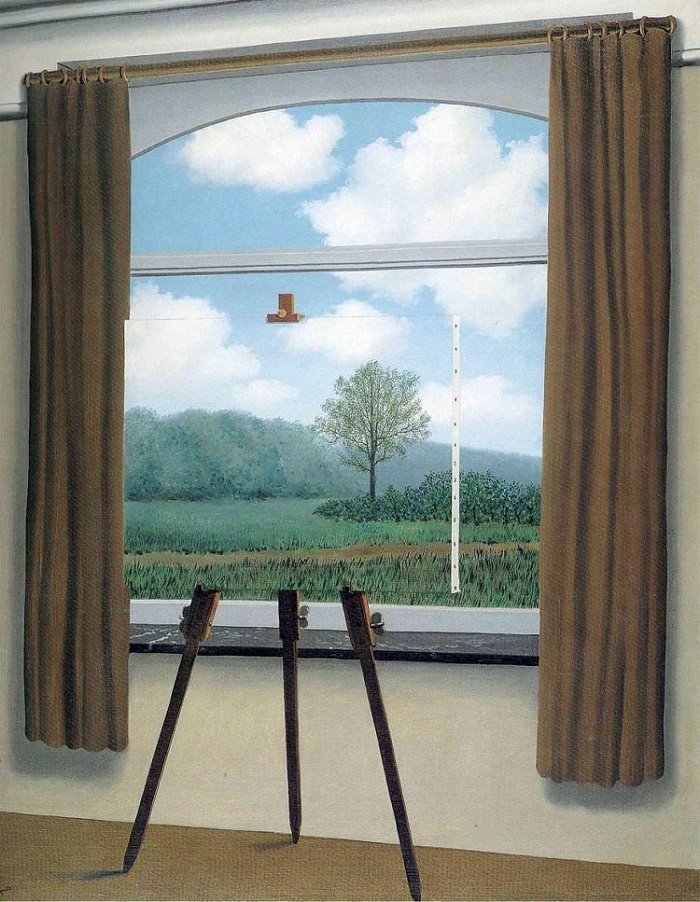

In contrast to Dalí’s often obscene and intentionally shocking imagery, René Magritte used realistic painting techniques to present philosophical conundrums about the nature of representation and its relation to reality and language. In The Human Condition, Magritte depicts the way a painting’s representation “replaces” reality, leading us to consider the many assumptions we make about realistic images and their relationship to what they represent.

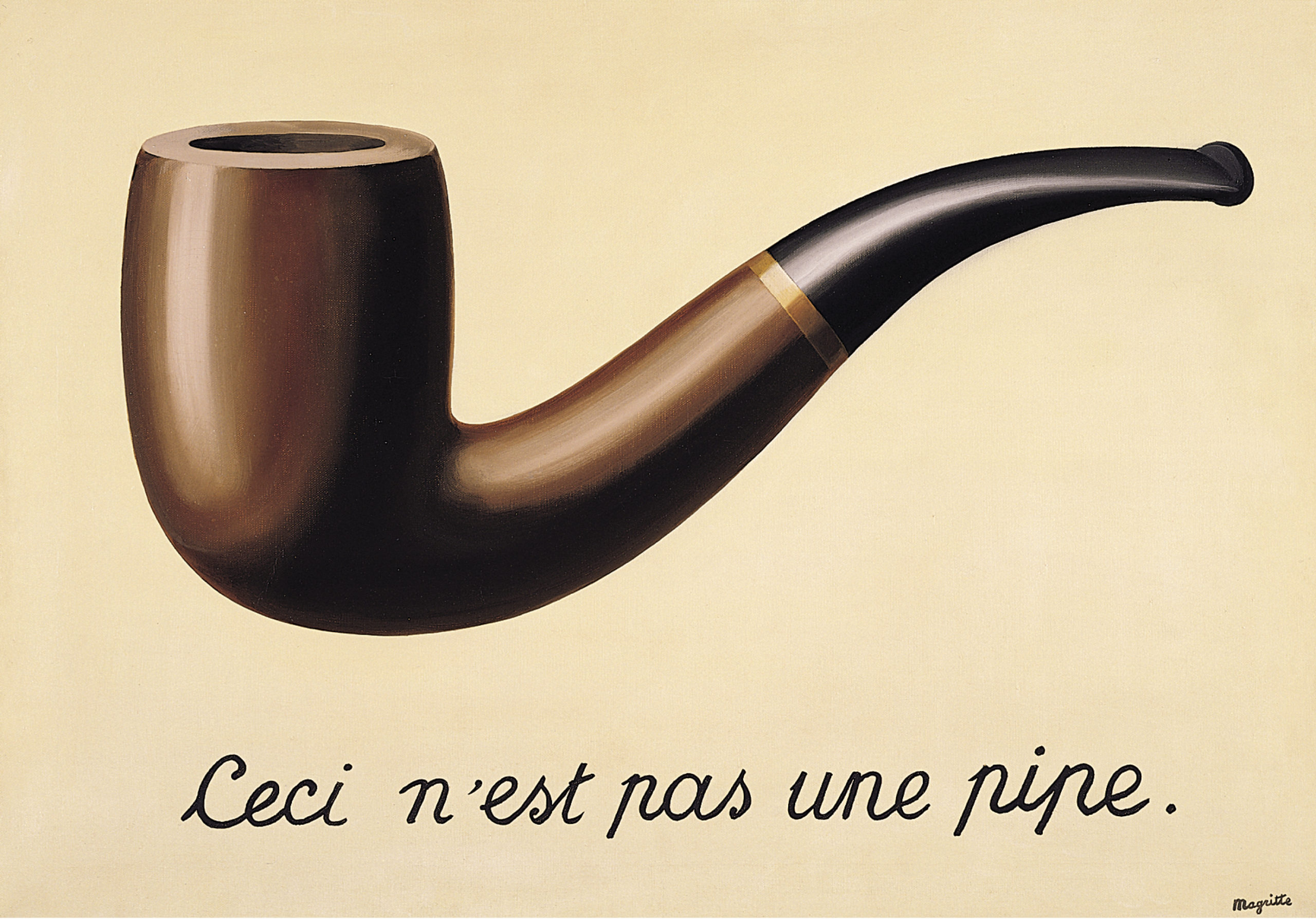

The Treachery of Images presents the disjunctions between the written phrase “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (This is not a pipe) and the depiction of a pipe above it. Representation is not reality, although it may look like it; nor is language to be trusted as a source of truth about what is real. The painting of a pipe is not a pipe; but the word “pipe” is not a pipe either. By undermining comfortable assumptions about the human ability to understand reality through language and representation, Magritte’s works demonstrate that we make the world we think we know. Everything is, in the end, a question of representation (in words or images) in which we choose to believe, or not.

Additional resources:

Read a biography of Giorgio de Chirico at the Guggenheim Museum

Read a biography of Yves Tanguy at the Guggenheim Museum

Surrealist Techniques: Collage

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

An overwhelming dream

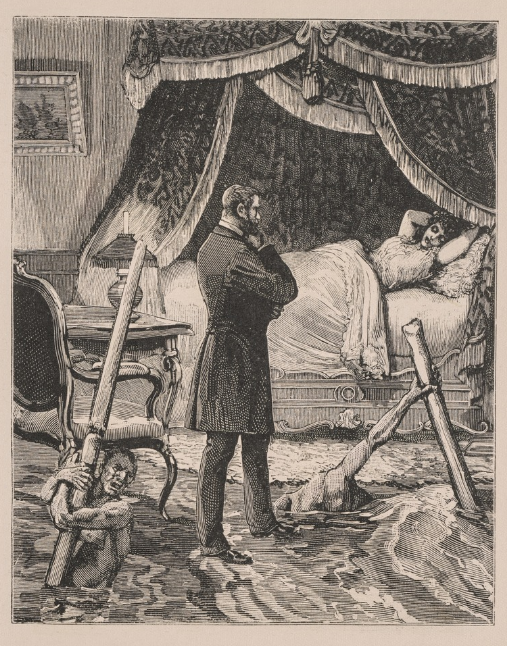

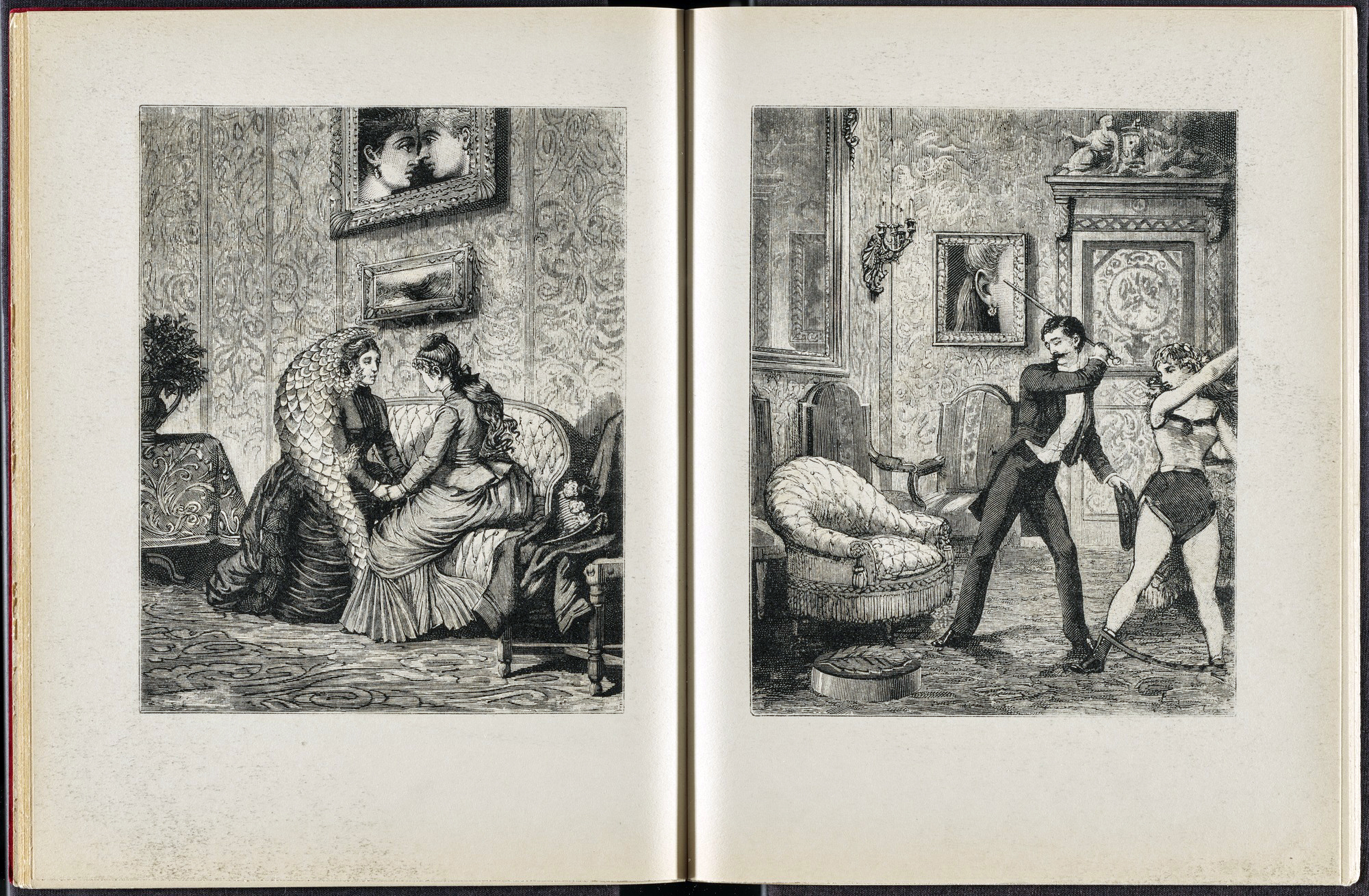

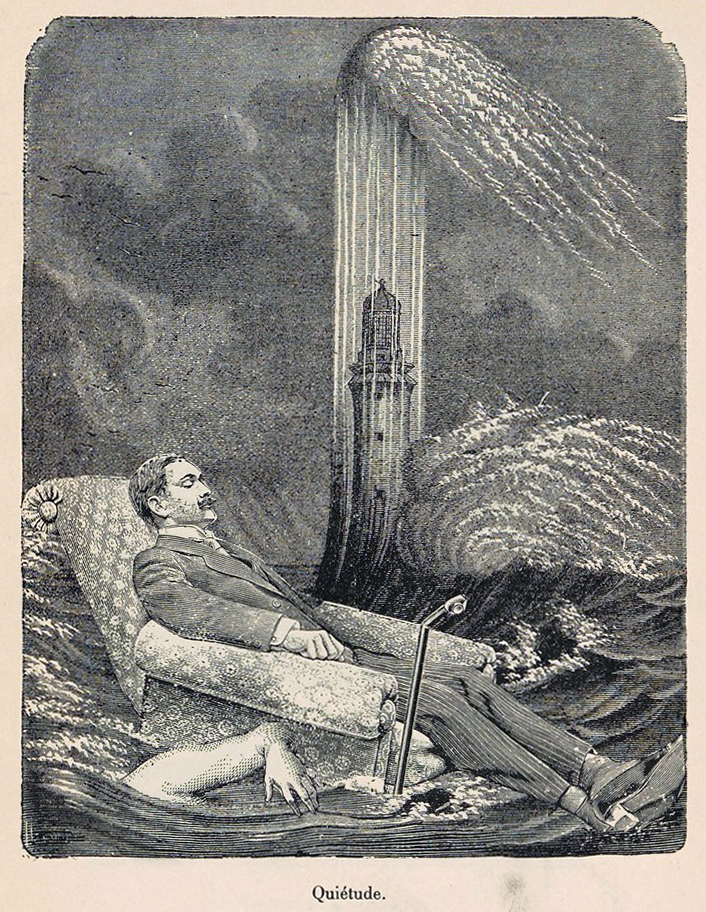

A woman sleeps in an elaborately decorated bed hung with fringed and tasseled curtains. A bearded man dressed in a frock coat stands in the bedroom and contemplates her, his chin in his hand. Behind him loom a disproportionately large table and chair, and under his feet the floor is flooded. He ignores both the surging waters and the two nude men at his feet clutching spars, apparent victims of a shipwreck.

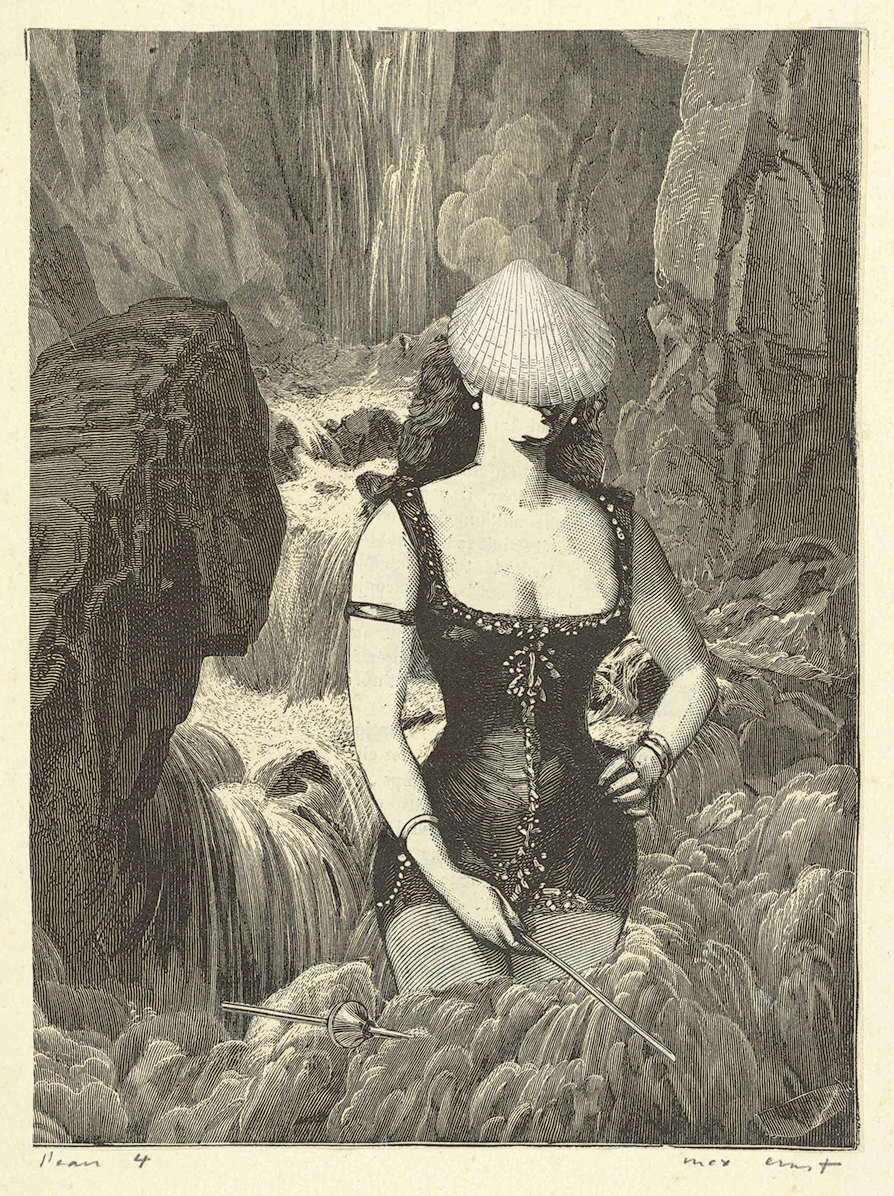

We are looking at one of the many wildly incongruous scenes that make up Max Ernst’s Surrealist collage novel Une Semaine de Bonté (A Week of Kindness) This image of a man studying a sleeping woman directly suggests a key influence on Ernst and the Surrealists in general, the psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud, particularly his study of dreams.

Following Freud, the Surrealists considered dreams a principal means to gain access to the unconscious, and they published many accounts of their own dreams in the journal La Révolution Surréaliste. Here, Ernst collaged together images cut from old book illustrations to depict a dream-like scene that has materialized in a woman’s bedroom and threatens to completely overwhelm the presumed dreamer and her observer.

Irrational juxtaposition

The Surrealists saw collage as a means to enact what they considered to be the fundamental poetic activity of the unconscious mind, the combination of disparate entities to create a new thing. Both Surrealist poets and artists used collage techniques. Like automatic writing, collage allows writers and artists to rapidly combine and juxtapose pre-existing elements, whether words or images, and transform them into new creations. This irrational juxtaposition of pre-existing elements mirrors the construction of dreams, which also bring together seemingly unrelated things to create strange narratives and scenes.

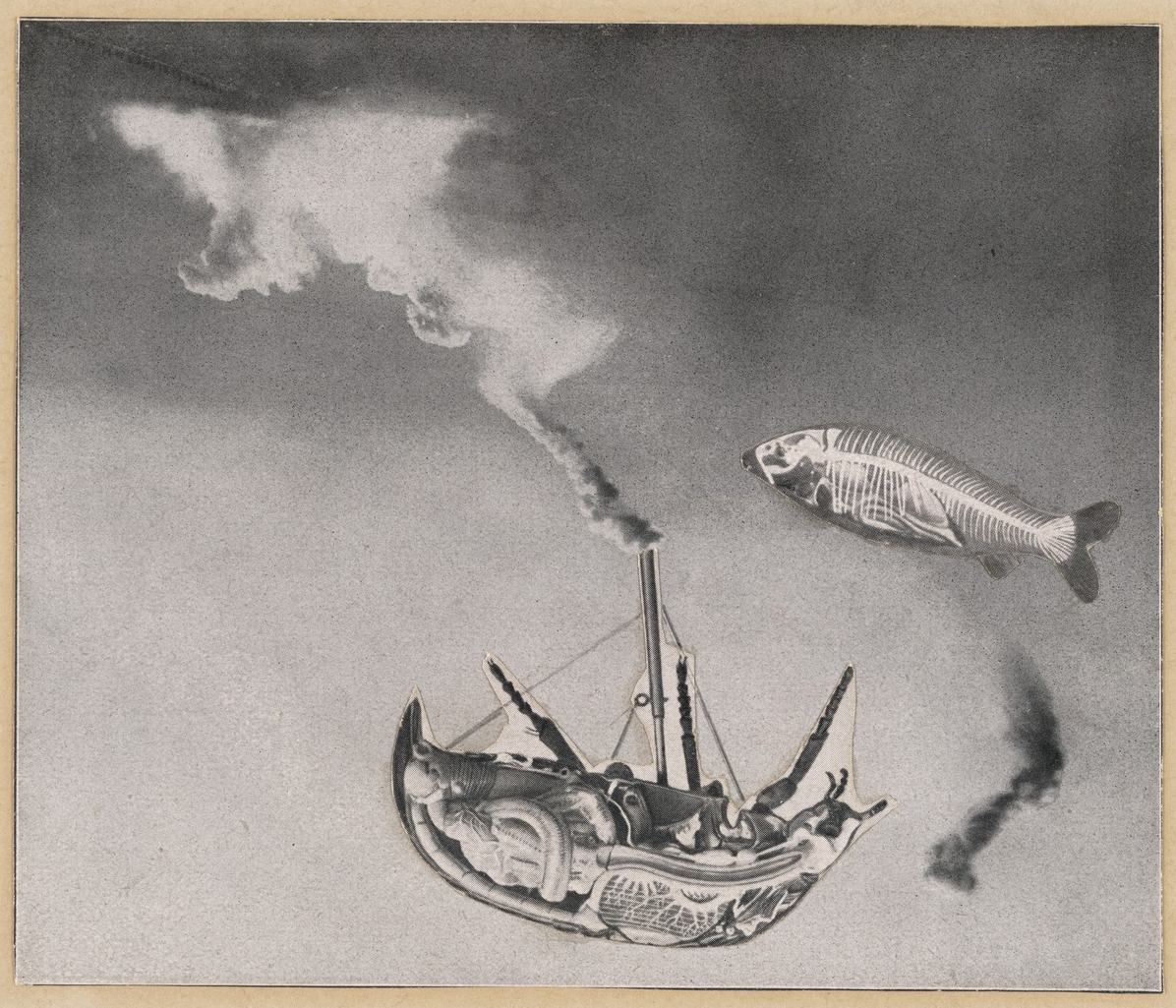

In Here Everything is Still Floating Max Ernst collaged images of a fish skeleton and a beetle onto a military photograph of an aerial bomb attack, thereby creating a seascape in which a steamboat encounters an enormous ghostly fish. We can identify the individual source images if we look closely, but they have been transformed by their new context, and their original significance is no longer relevant. They have become part of a new world.

Manifestations of the unconscious

Ernst was the first visual artist to join the Surrealist movement, and his early Dada collages such as Here Everything is Still Floating were an important catalyst for the development of Surrealism. As a Dadaist Ernst initially used collage techniques of juxtaposition to violate established expectations and rationality. For the Surrealists, however, the disruptions and dislocations of collage were not just arbitrary iconoclasm; they were direct manifestations of unconscious thinking.

The phrase

as beautiful as the chance encounter of an umbrella and a sewing machine on a dissecting table

from Les Chants de Maldoror by the nineteenth century writer known as the Comte de Lautréamont was a touchstone for the Surrealists. It embodied their notion that the union of disparate objects or words can result in new and marvelous creations. Ernst described the mechanism of collage in a more general way as “the coupling of two realities, irreconcilable in appearance, upon a plane that apparently does not suit them.”\(^{[1]}\) What arises from that coupling is something previously unknown, a new reality.

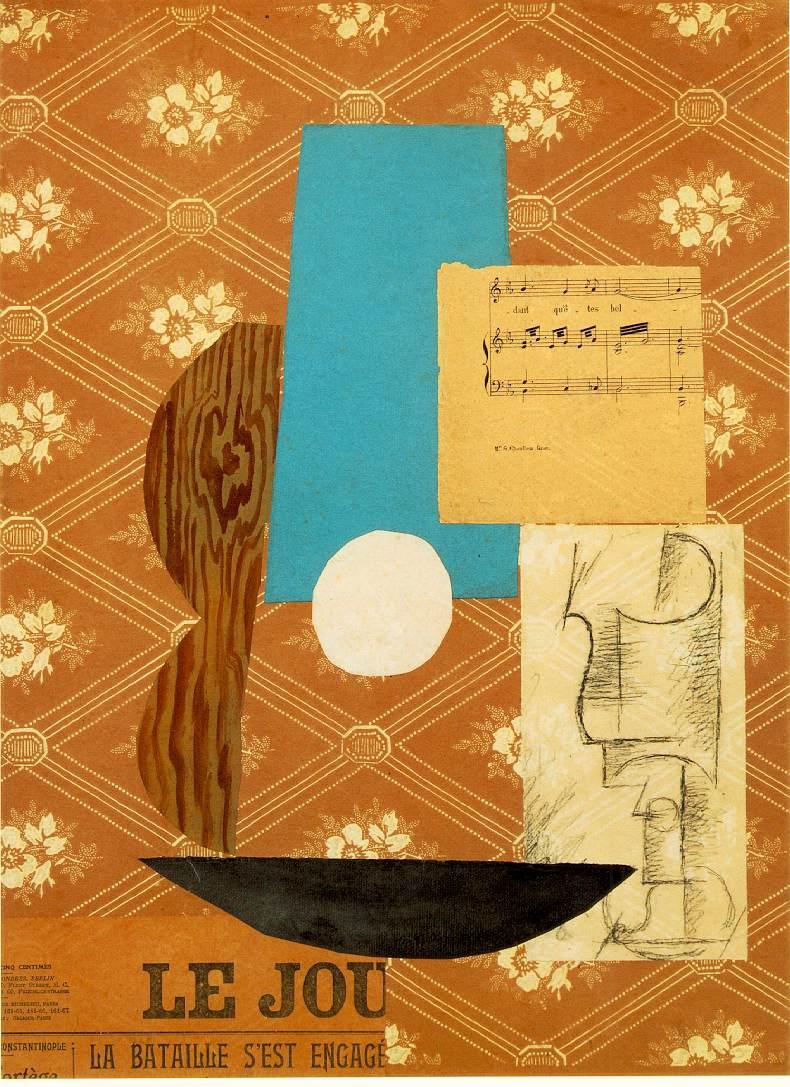

Transforming ordinary things

Collage techniques were widely used in the 19th century by women making albums and decorative objects. In the 20th century they were adopted by the Cubist painters Picasso and Braque, who used them to expand their exploration of representational strategies and pictorial form.

Unlike the Cubists, the Surrealists were not interested in formal issues or in what they saw as narrowly aesthetic concerns. They viewed collage as a means to transform ordinary things, such as wallpaper, and turn them into points of entry to another world.

In his collage novels such as Une Semaine de Bonté, Ernst exploited the potential of collage to scramble the order of so-called reality to an extreme degree. He placed individual collage images of an imaginatively reordered universe into an extended visual narrative based on an illogical series of displacements and irrational re-integrations. To stress the independent existence of the imaginatively created world, these collages are seamless. Unlike Cubist collages, where the disparate parts remain clearly visible, Surrealist collages conceal the sutures between the constituent units, thereby emphasizing the final image’s “reality” rather than the procedures and materials of its creation.

A foundational technique

The basic mechanism of collage, irrational juxtaposition or the bringing together of radically incompatible things, was foundational for Surrealism, just as it is fundamental to the way dreams work according to Freud. Salvador Dalí combined collage and oil paint in some of his early Surrealist works, but even when he did not incorporate literal collage elements, the conceptual mechanism of the technique remains at the heart of his work. In Illumined Pleasures we see Dalí’s sleeping profile in the center surrounded by the incongruous objects of his unconscious thoughts.

In the foreground, directly below Dalí’s profile, a bearded man in a suit grabs a woman in a nightgown while both stand in water. Note the similarity to the Ernst scene we first looked at above; both works illustrate imagery Freud described as frequently appearing in dreams. Surrounding Dalí’s profile are what he called his “obsessions,” and these are grouped together in a collage-like presentation. Some of the figures are themselves conjoined images, such as the smiling woman’s head, which is also a foaming beer stein, and her neck, which is also a girl’s face in the shape of a mug.

The conceptual mechanism of collage is also central to many of the paintings of René Magritte, which depict the irrational juxtaposition of disparate objects in a realistic style. In Time Transfixed a steam-train engine enters a room through the fireplace. The scale is impossible, but the details of the representation are so meticulous, including the cast shadow of the train and the steam going up the chimney, that we are led to consider this an accurate depiction of the world of dreams where such incredible combinations are commonplace.

The Surrealist juxtaposition of disparate entities, be it literal or conceptual, requires recognizable elements to achieve its surprising and innovative effects. This reliance on realistic representation differentiated Surrealism from most modern art movements, which rejected realism as an outdated concern with subject matter rather than artistic form. For the Surrealists, however, dedication to narrowly artistic concerns such as form, style and technique was an abdication of artists’ potential to change the world. Collage, with its ability to reshape reality in challenging, but still recognizable ways, was a central technique in the Surrealists’ revolutionary endeavors. It showed precisely how the mind could re-make the world in a concrete way, by using new and unexpected combinations of existing things to create a new reality.

Notes:

- Max Ernst, Beyond Painting, translated by Dorothea Tanning. (New York: Wittenborn, Schultz, 1948), p. 13.

Additional resources:

Read a biography of Max Ernst at the Guggenheim Museum

View Une Semaine de Bonté, Volume II: Water at MoMA

View Une Semaine de Bonté, Volume 3: The Court of the Dragon at MoMA

Surrealist Photography

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

An enigmatic image

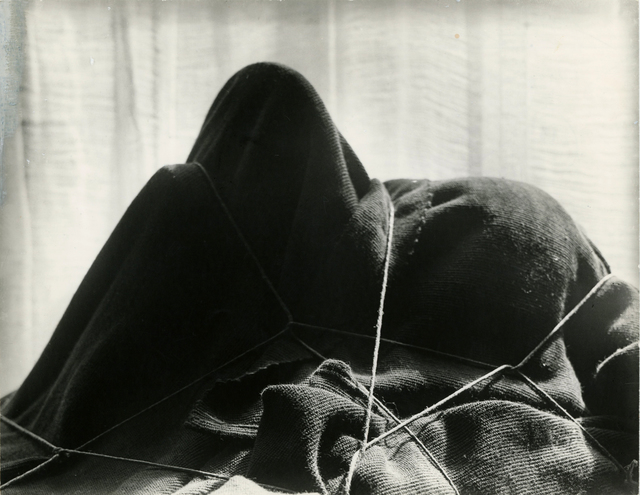

Man Ray’s photograph of a mysterious object or objects covered in a blanket and tied up with rope is the opening image of the Surrealists’ first journal, La Révolution Surréaliste. It appeared without caption or attribution in the middle of an essay announcing the Surrealists’ dedication to dreams and revolution. Readers were left to determine its significance on their own. Perhaps it was intended to represent the mysteries of the unconscious bound up and hidden beneath the surface of ordinary things. Perhaps it referred to the as-yet-undisclosed contents of the magazine that the reader would encounter in the following pages.

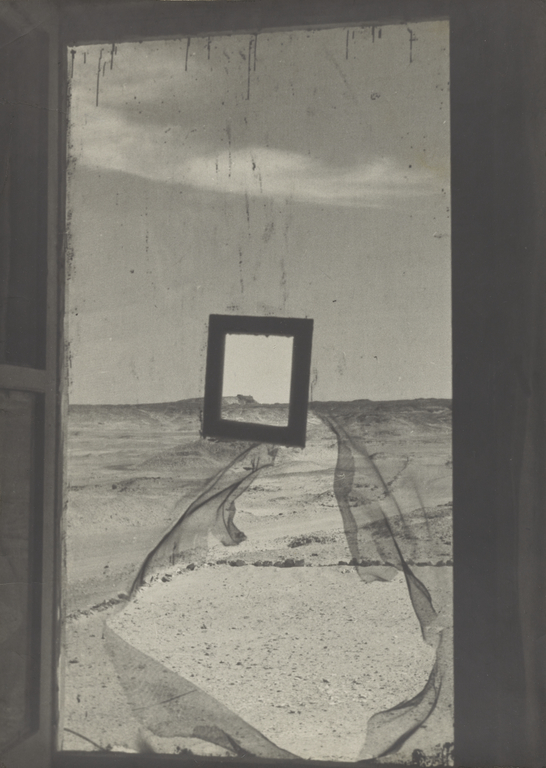

Most likely it was intended to appeal to the unconscious desires of each individual reader. Surrealism as a movement was dedicated to creating works that not only expressed their author’s unconscious mental activity, but also provoked such activity in the viewer. The Surrealists developed a number of tools for achieving this end, including irrational juxtapositions, suggestion, and subversive realism, all of which were mobilized in Surrealist photography.

Rayographs

Photography played an important role in Surrealism from the movement’s inception. The New York Dadaist Man Ray moved to Paris in the 1920s and became an early member of the Surrealist group as well as working as a successful fashion photographer. The Surrealist leader André Breton admired his Dada rayographs for the surprising ways they both revealed and transformed common objects. Rayographs, also known as rayograms or photograms, are made by placing objects on photo-sensitive paper and briefly exposing them to light. The silhouettes of the objects are recorded on the paper as white unexposed areas, and can create unexpected patterns and suggestive images.

Photographic proof

Man Ray’s photographs liberally illustrate Surrealist journals, as do many photographs from anonymous sources. In many instances these photographs were intended as visual proof of Surrealism’s existence in the world. Traditionally regarded as a means to create factual visual records, photographs were used by the Surrealists both to document Surrealist occurrences and to call into question the nature of reality.

During early debates on the possibility of a Surrealist visual art, Pierre Naville published a statement that the only acceptable types of visual production were non-artistic photographs that revealed the Surrealist nature of reality. Although this restrictive view of Surrealist art did not prevail, interest in photography as a form of Surrealist documentation endured and became an important aspect of Surrealist visual production.

Breton’s autobiographical texts Nadja and L’Amour fou were illustrated with photographs by Man Ray, Brassaï, Boiffard, and others. The photographs document the objects and Paris locations described in Breton’s narrative. They are presented as a form of evidence that implicitly attests to the truth of Breton’s description of his Surrealist adventures.

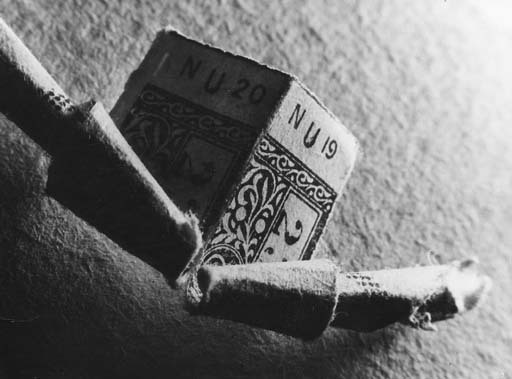

Man Ray’s photographs of fashionable hats and Brassaï’s photographs of discarded bus tickets were used to illustrate Surrealist essays on the widespread presence of erotic forms and automatism in daily life. The photographs were intended to document how the common objects of the modern world are profoundly shaped by unconscious, frequently sexual, desires. Women’s hats take on phallic and vaginal forms, while the tickets and other odds and ends people drop on the street have been folded and fondled into elaborate and suggestive shapes.

The Surrealists called these manipulated objects involuntary sculptures and, like doodles and Surrealist artworks created by using automatic techniques, they understood them to be the direct result of unconscious creative activity.

The strangeness of the world

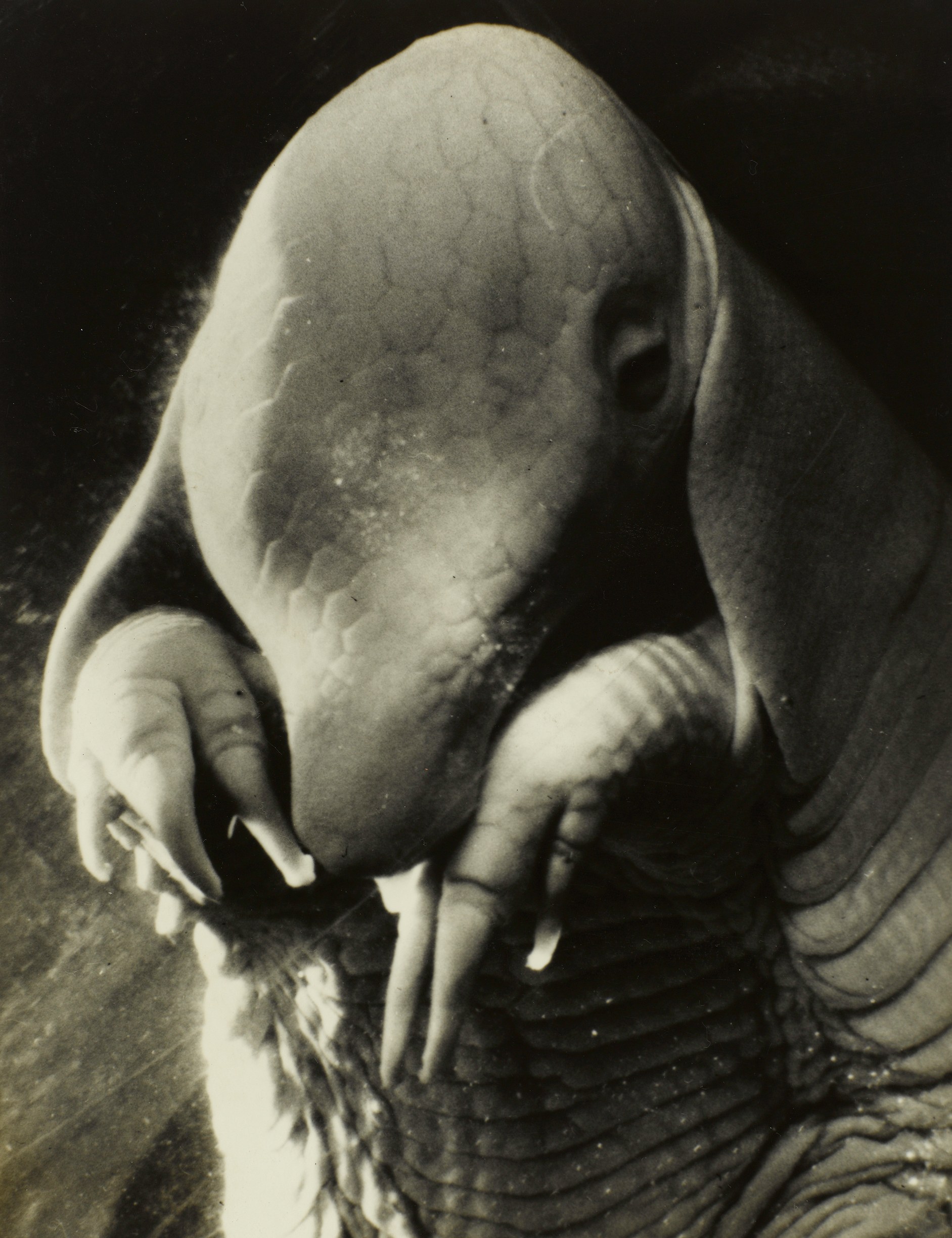

Surrealist photographs were also used to reveal the strangeness of the world we think we know, often by simply presenting it in a new way. Dora Maar titled her photograph of a baby armadillo after the anti-hero of Alfred Jarry’s famously transgressive and iconoclastic play Ubu Roi (1896), which was much admired by the Surrealists.

The close-up image of the animal’s unfamiliar form is startling in itself, but by connecting the armadillo to Père Ubu, Maar created an emotional resonance for viewers familiar with the character. Suddenly, the small animal is transformed into a large, greedy, and violent human being — what was perhaps merely strange becomes monstrous. This is possible in part because of the way the photograph distorts our sense of scale by close-cropping and isolating the animal within the frame.

Innovative techniques

In addition to presenting photographs as Surrealist documents of the unexpected strangeness of reality, photographers associated with Surrealism experimented with darkroom techniques to create bizarre, often unpredictable, results.

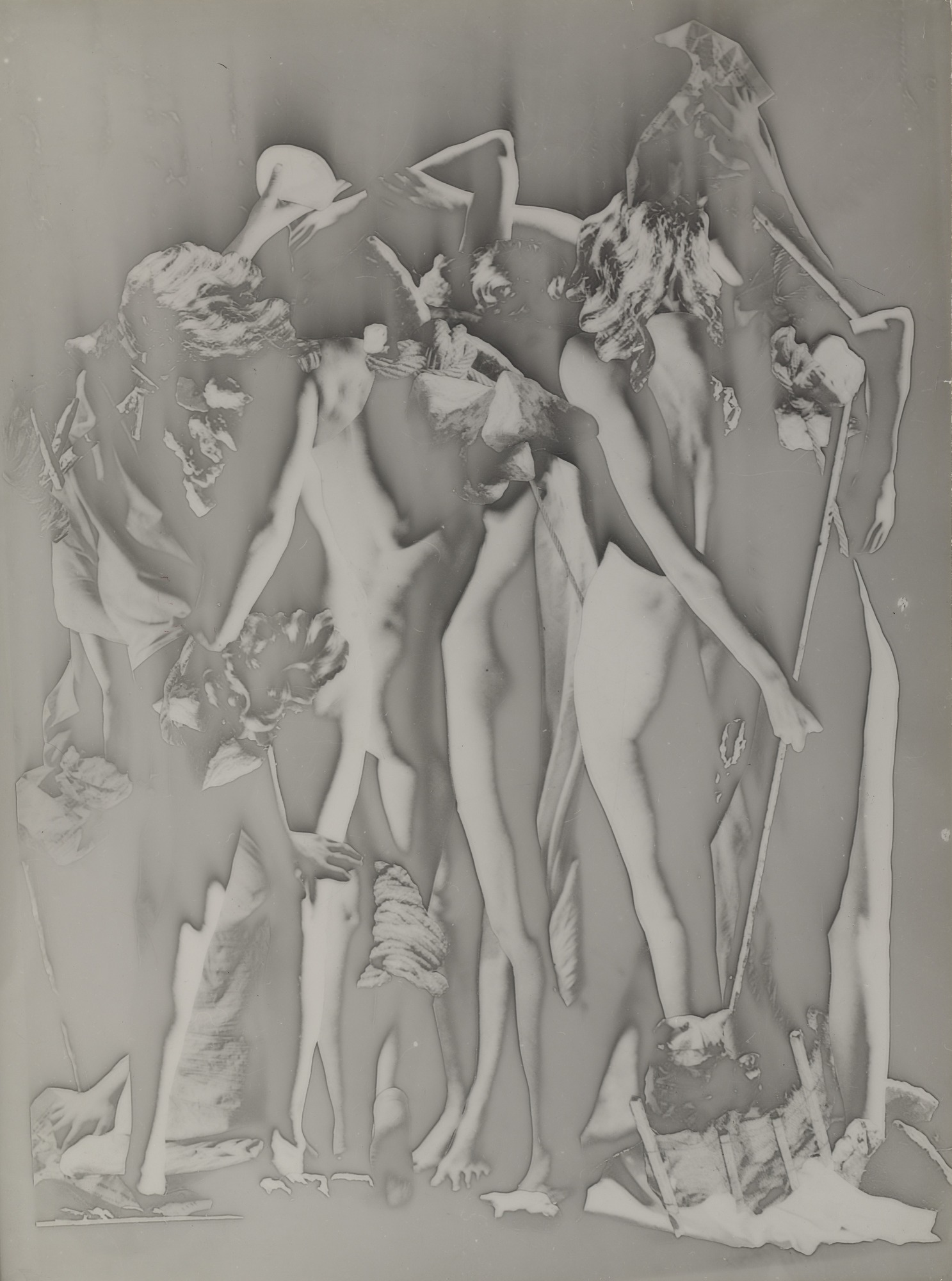

In works such as The Secret Gathering, Raoul Ubac exploited the unsettling effects of double exposures and solarization (extreme over-exposure of film, which reverses tones) to suggest photography’s capacity to reveal a Surrealist reality hidden from ordinary vision. Based on photographs of two nude women, Ubac used darkroom manipulations to transform the original photographs into the suggestion of an other-worldly gathering of semi-human beings. Because we can still see some body parts clearly, we are led to think that this strange photograph may be a faithful document of a surreal world.

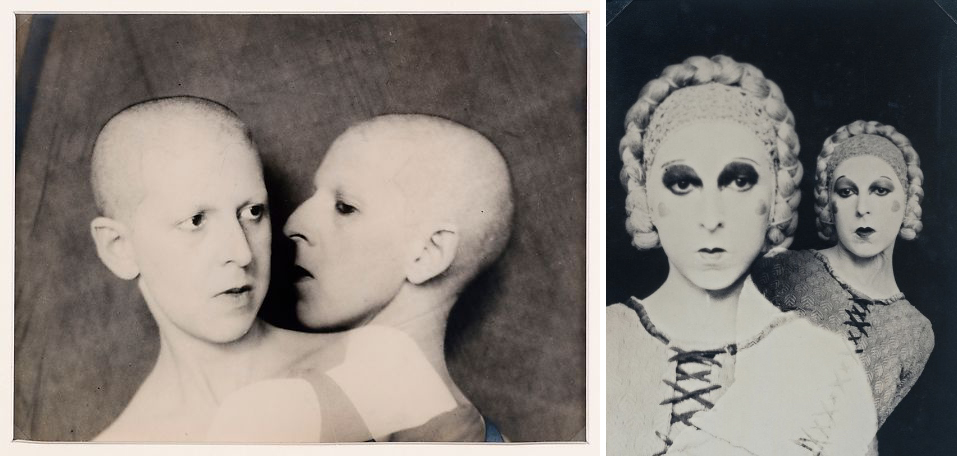

In Que me veux tu? (What do you want from me?) Claude Cahun similarly used darkroom manipulation to present herself doubled. Cahun’s self-portraits use multiple exposures, costumes and varied strategies of self-presentation to question the nature of individual identity. Her photographs are unusual in the context of Surrealist photography both as self-portraits and as images of a woman made by a woman.

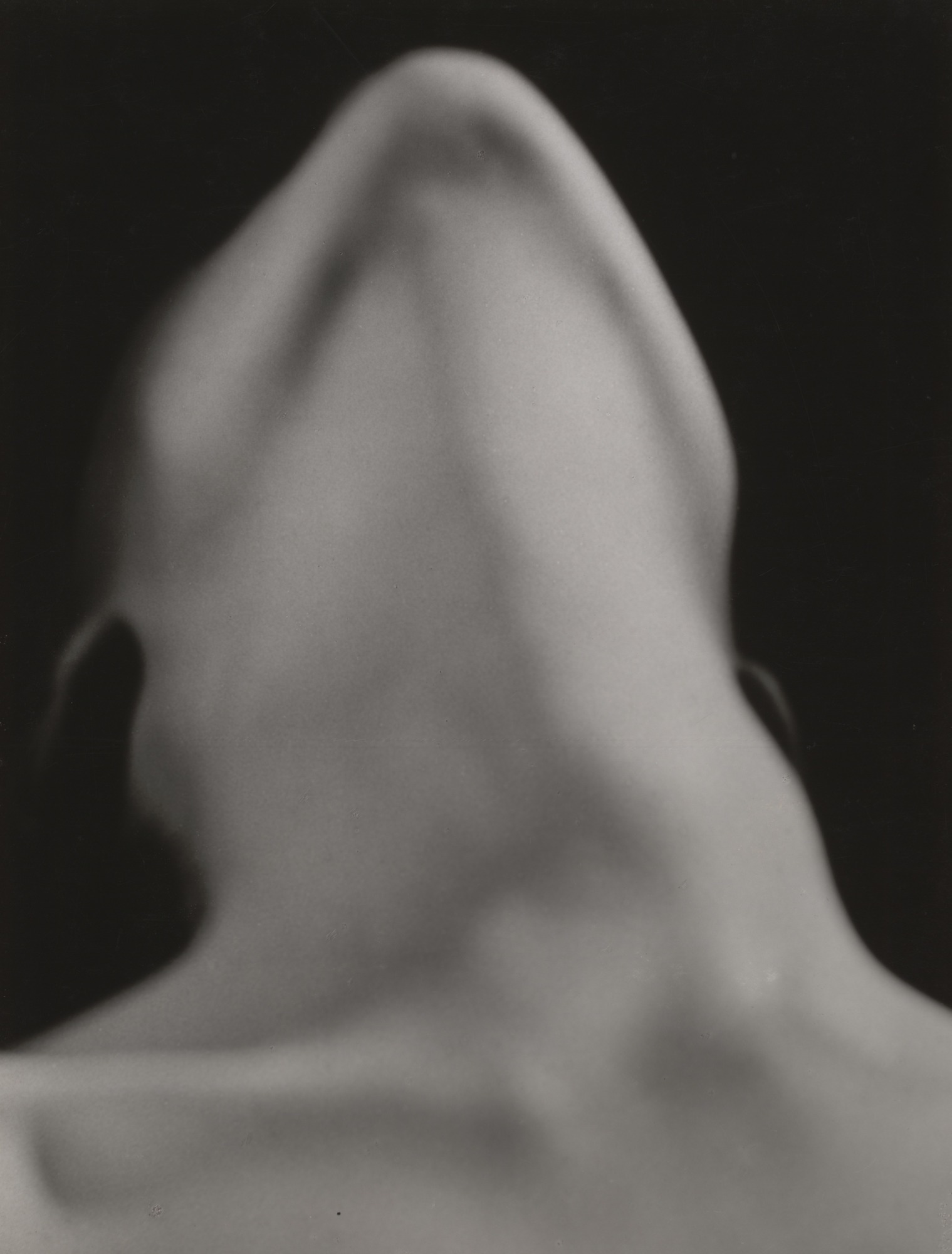

Women’s bodies were a favored subject for Surrealist photographers. Employing unusual angles, cropping, distorting lenses, and selective focus, Surrealist photographers transformed the body according to their desires and imagination. The infinitely malleable forms of the body served as revelatory means for Surrealist vision. Man Ray’s Anatomies, for example, transforms a woman’s chin and neck into a phallic form, in keeping with Freudian theories of fetishism.

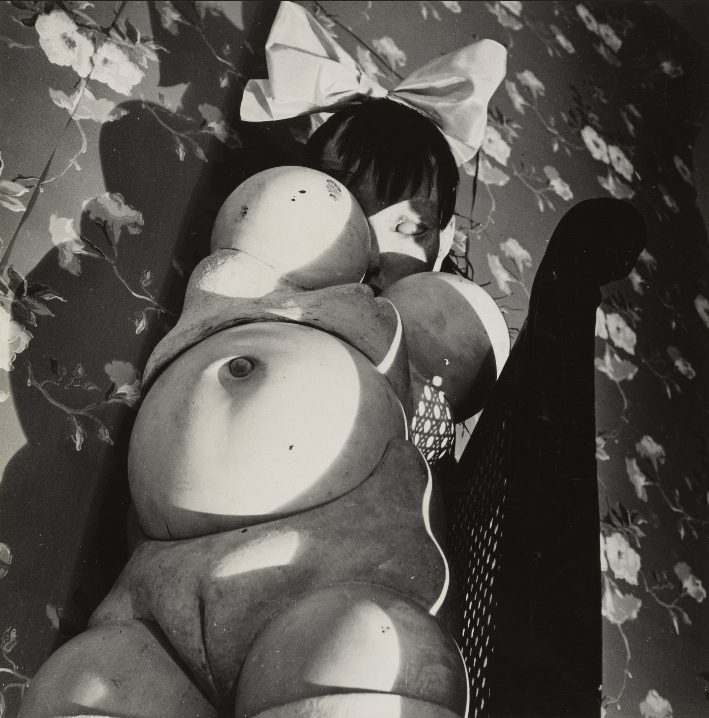

Hans Bellmer combined sculpture with photography in the creation of his doll, whose body changed with each image, fragmenting and multiplying body parts according to the erotic desires of its maker.

Photography and film as Surrealist media

Some scholars consider photography to be the most effective of the Surrealists’ visual productions in part because of its ability to reveal hidden realities and to demonstrate the transformative powers of vision. In addition, photography is less restricted by the expectations and artistic conventions that affect the traditional art forms of painting and sculpture.

Film also seems to be a particularly appropriate Surrealist medium, as was noted in the first published discussion of the possibilities for Surrealist visual art. The Surrealists recognized that film could literally show the flow of unconscious thought and create extended dream-like visual experiences. During the Dada period the group made a practice of moving from theater to theater, watching only parts of the films being screened. In this way they experienced the unfolding of a suggestive collection of disparate images without submitting to the logic of a single narrative.

Luis Buñuel was the most dedicated and successful Surrealist filmmaker. Salvador Dalí collaborated with him in the creation of the two most important and notorious Surrealist films, Un Chien andalou (1929) and L’Age d’Or (1930). While film never became the primary focus of Surrealist visual production, the influence of Surrealism on photography and filmmaking has been immense and endures to the present day.

Additional resources:

Read more about Man Ray at MoMA

See all of the Rayograms from Champs Délicieux at the J. Paul Getty Museum

Surrealist Exhibitions

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

Surrealism was the first modern art movement to make the creation and design of exhibitions a major focus of its activity. The group transformed the art exhibition from a traditional display of artworks into a staged venue intended to provoke new ideas and experiences. The contents of Surrealist exhibitions were typically eclectic and included works by Surrealist artists, other artists and non-artists admired by the Surrealists, as well as objects of various sorts and artifacts from cultures perceived as “primitive.”

Exhibitions as Surrealist experiences

From the beginning, Surrealist exhibitions were intended to provide a Surrealist experience for viewers and lead them to perform their own acts of Surrealist imagination. The juxtaposition of disparate works and objects in the extended space of an exhibition would, it was hoped, provoke the creation of a new world, using the same mechanism as that employed in a Surrealist collage.

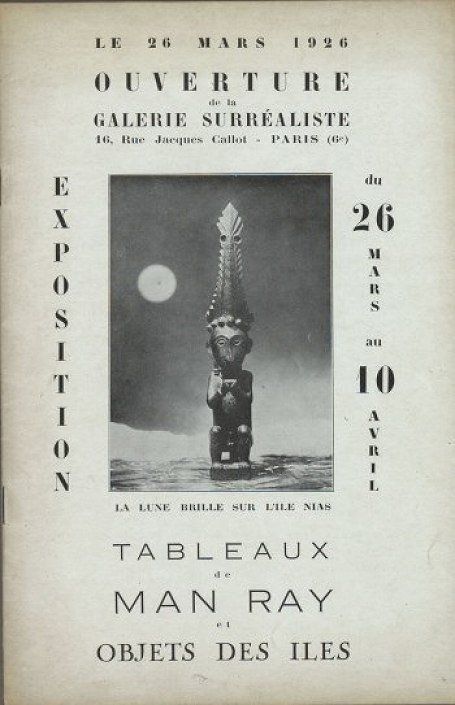

During the 1920s the Surrealists ran their own art gallery, which staged several unconventional exhibitions. Man Ray’s work was exhibited with art from Oceanic cultures, while Tanguy’s paintings were paired with Native American works. These non-European works were also seen as products of unconscious thinking, and as such fully equal to the works of Surrealist artists in providing insight into the immense creative resources of the arational mind.

Contempt for art market values

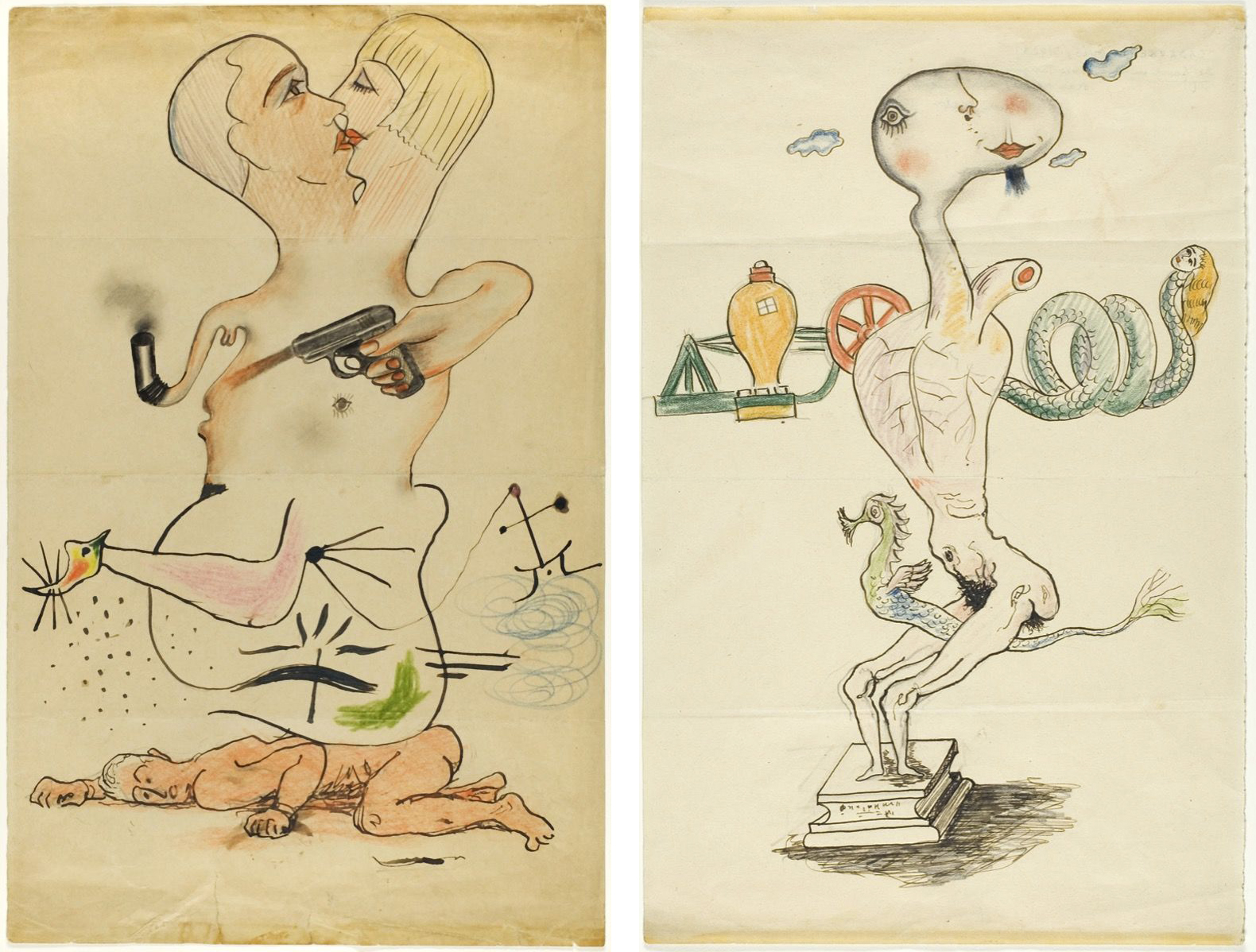

The Surrealist Gallery also presented an exhibition of “exquisite corpse” drawings. These are drawings of figures made by a collaboration of three to five people using a method derived from parlor games. Each person draws part of the body and then folds the paper over so the person drawing the next section cannot see the previous drawing. Once the figure is completed the paper is unfolded and the strange juxtapositions of the various parts become a new Surrealist entity.

The “exquisite corpse” method demonstrated many basic Surrealist principles. Both artists and non-artists participated in the making of exquisite corpses, which, like all Surrealist works, were not intended to be the result of artistic skill. The group nature of the drawings as well as their arbitrary automatic creation were intended to subvert any attempt to exalt the individual artist and his or her talent. These are drawings anyone can do. The exhibition of exquisite corpse drawings in the Surrealist Gallery demonstrated the group’s contempt for conventional assumptions about the value of art and the skills of artists that underpin the art market.

Irrational categories of display

The Surrealist Gallery did not survive very long, but the Surrealists continued to stage exhibitions, which grew in scope and ambition during the 1930s. The Surrealist Exhibition of Objects was held in the gallery of Charles Ratton, a dealer in African, Oceanic, and Native American arts. This 1936 exhibition brought together over two hundred objects divided into categories, including Surrealist objects as well as natural objects, interpreted objects, mathematical objects, found objects, readymade objects, and so-called “savage” objects (the art of Oceania and Native Americans).

The eclectic presentation brought together objects typically exhibited in very different contexts: art galleries, natural history museums, anthropological museums, science museums, and flea markets. By upsetting the conventional categories of knowledge and presenting an alternative, illogical system, the Surrealists demonstrated how context creates meaning. The exhibition undermined the supposedly rational divisions of human knowledge using irrational strategies of display.

Surrealist environments

The most famous Surrealist exhibition was the 1938 International Exhibition of Surrealism at the Beaux Arts Gallery in Paris. It displayed 300 works and objects by over sixty artists from fifteen different countries. The scale of the exhibition was impressive, and its installation design made it truly remarkable. Visitors were enfolded in an entire Surrealist environment.

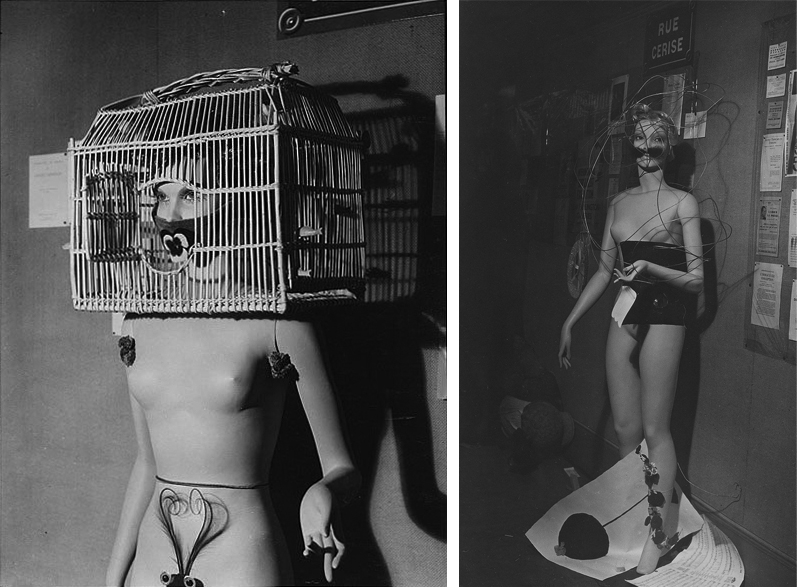

In the lobby was Dalí’s Rainy Taxi, an old car surrounded by vines and installed with a system of tubing that created a downpour in the interior. Two mannequins, one with a shark’s head and one with a woman’s, sat inside surrounded by lettuce and covered in live snails.

Leading from the lobby was a long hallway lined by twenty mannequins, each costumed by a Surrealist artist. At the end of the passageway was the main hall of the exhibition, designed by Marcel Duchamp. The ceiling was hung with hundreds of sacks of coal, while the floor was covered with dead leaves and had a pool with water lilies and reeds. In the center of the room was an old iron heater, and in each corner were large beds covered in satin quilts.

Paintings were hung on the walls as well as on two revolving doors next to the heater. Surrealist furniture and objects were displayed throughout. The room was unlit, and visitors were given flashlights to use during their journey through the exhibition. During opening night a German military march was played through a loudspeaker, coffee was roasted to emanate the “perfumes of Brazil,” and a dancer performed a dance titled “The Unconsummated Act” in and around the pool. For the most part art critics mocked the exhibition, but it was an enormous popular success.

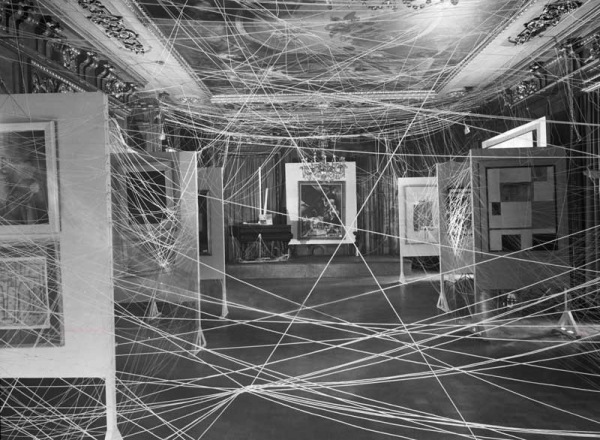

The elaborate installation of the 1938 exhibition was not repeated, but in 1942 Duchamp designed another installation for the First Papers of Surrealism Exhibition in New York City. He wound a mile of string into a labyrinth that covered the walls and art works like an enormous spider web. Visitors were literally enmeshed with the Surrealist works in the environment. The illogical space he created seemed to be more a physical manifestation of mental space than an environment to be explored by a human body.

Salvador Dalí took the concept of Surrealist installation into the realm of advertising, fashion, and popular entertainment. In addition to designing windows for department stores in the 1930s, he erected the Dream of Venus pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. This full-scale fantasy environment turned Surrealist eroticism into a kind of popular burlesque. Visitors entered between two huge legs, and the interior included a grotto with a ceiling covered in inverted open umbrellas, a new version of Rainy Taxi, a 36-foot long sofa with a reclining nude, and seventeen women costumed as mermaids cavorting for viewers in a furnished aquarium.

Surrealist exhibitions broke down conventional distinctions between art and non-art, and thwarted the consumption of creative works as commodities. In addition, the Surrealists transformed the conception of the exhibition from a neutral site for the display of objects into a creative production in its own right. The later developments of environments, happenings, and installation art are all indebted to the Surrealists’ conception of the art exhibition as an experience rather than simply a showcase for artworks.

Additional resources:

Read more about the First Papers of Surrealism exhibition at the Tate Papers

Roger Schall’s photos of the 1938 Surrealist exhibition at MoMA

Surrealism and Women

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

Women as objects of fear and desire

Women were a central subject in Surrealist art. Male Surrealist artists often portrayed fragmented, deformed, and dismembered female bodies as objects of violent erotic imaginings. This may be attributed, at least in part, to the Surrealists’ engagement with Freudian psychoanalytic theories, in which the female body is both the primary object of male heterosexual desire and a source of great anxiety resulting from male fears of castration. Women thus represent the greatest source of erotic satisfaction, while also inspiring disgust and terror.

With her seemingly endless permutations and multiplication of body parts, Hans Bellmer’s fetishistic doll can be seen as an objectification of these powerful and contradictory emotions. The Surrealists’ perception of women as terrifying but erotic objects also appears in their fascination with the praying mantis. In the 1930s many Surrealist artists depicted this insect, whose female beheads and eats the male during or immediately following copulation. Max Ernst’s ironically titled The Joy of Life shows the insects in the foreground of an ominous jungle scene filled with half-hidden, menacing creatures.

Women as a source of inspiration

The other side of the coin was a tendency to idealize women as beautiful, mysterious sources of inspiration. The violated and debased female body is such a commonplace of Surrealist art that it may seem surprising that the Surrealists were dedicated to romantic love. This is more evident in Surrealist writing than in the visual arts, but it was an attitude that affected the personal lives of artists and writers alike.

Man Ray photographed the Surrealist poet Paul Eluard’s second wife Nusch as the beloved muse to whom he dedicated many love poems. The wives and lovers of the male Surrealists were often key figures in the movement even if they were not themselves artists or writers. They were celebrated in Surrealist art and writings and often directly participated in the movement by signing manifestos, making objects, and contributing to exquisite corpses and other group activities. Gala Dalí was the most prominent. First the wife of the Surrealist poet Paul Eluard, then the lover of Max Ernst, she ultimately became the wife of Salvador Dalí, who dedicated all his work to her, even signing her name to his paintings because she inspired them.

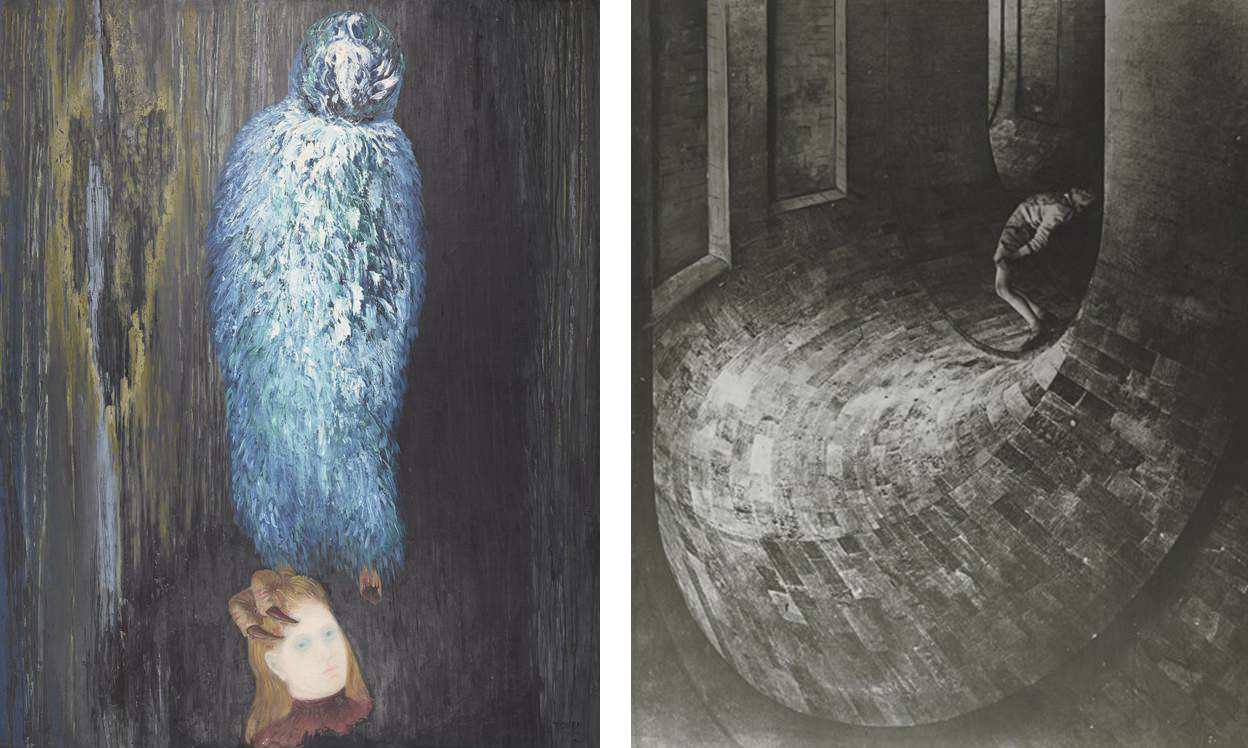

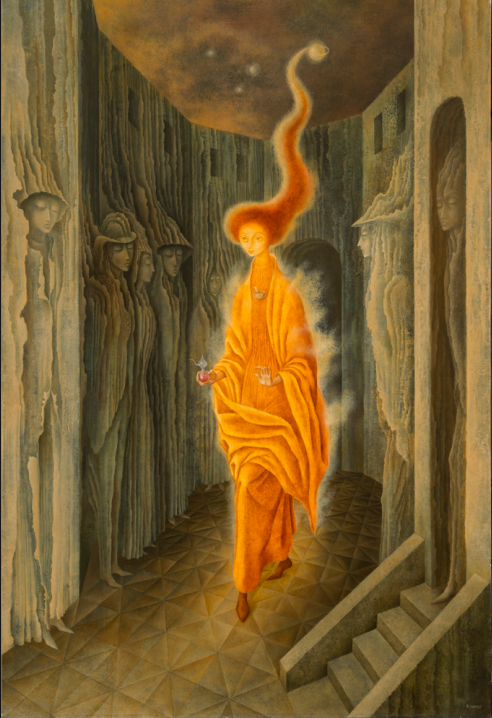

Women Surrealist artists

In the early years of Surrealism no women artists were members of the group, but this changed over time as the movement grew in size and influence. Many of the most well-known women associated with Surrealism became involved with the movement through their personal relationships with Surrealist men. Meret Oppenheim and Lee Miller both worked with Man Ray, in addition to making their own Surrealist works. Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning became involved with Surrealism through Max Ernst; Remedios Varo through the Surrealist poet Benjamin Péret; and Kay Sage through Yves Tanguy.

Leonor Fini exhibited with the Surrealists in the 1930s, as did the Czech Surrealist painter Toyen, and the photographers Claude Cahun and Dora Maar.

Surrealist women representing women

Given the Surrealist interest in creating art that manifested the unconscious and the prominence of Freudian themes in the work of male Surrealist artists, certain questions inevitably arise. How did female Surrealist artists represent their dreams and unconscious desires, and how are they different from the representations of male Surrealist artists? These are difficult questions to answer, in part because the Surrealists strongly rejected conformity. Although there are similarities between certain Surrealist artists, it is impossible to make sweeping generalizations about all male Surrealists, and this is equally true of the women.

Many of the women associated with Surrealism were as interested in women as an artistic subject as the male Surrealists were. Their representations of women are, however, notably different. While male Surrealist artists often depicted faceless, distorted, and violated female bodies, artists such as Carrington, Varo, and Fini portrayed women, including themselves, as young and beautiful. In depictions of their dreams and in their self-representations, women artists associated with Surrealism often seem to conform to male Surrealist idealizations of women as beautiful, child-like creatures inhabiting magical dream environments.

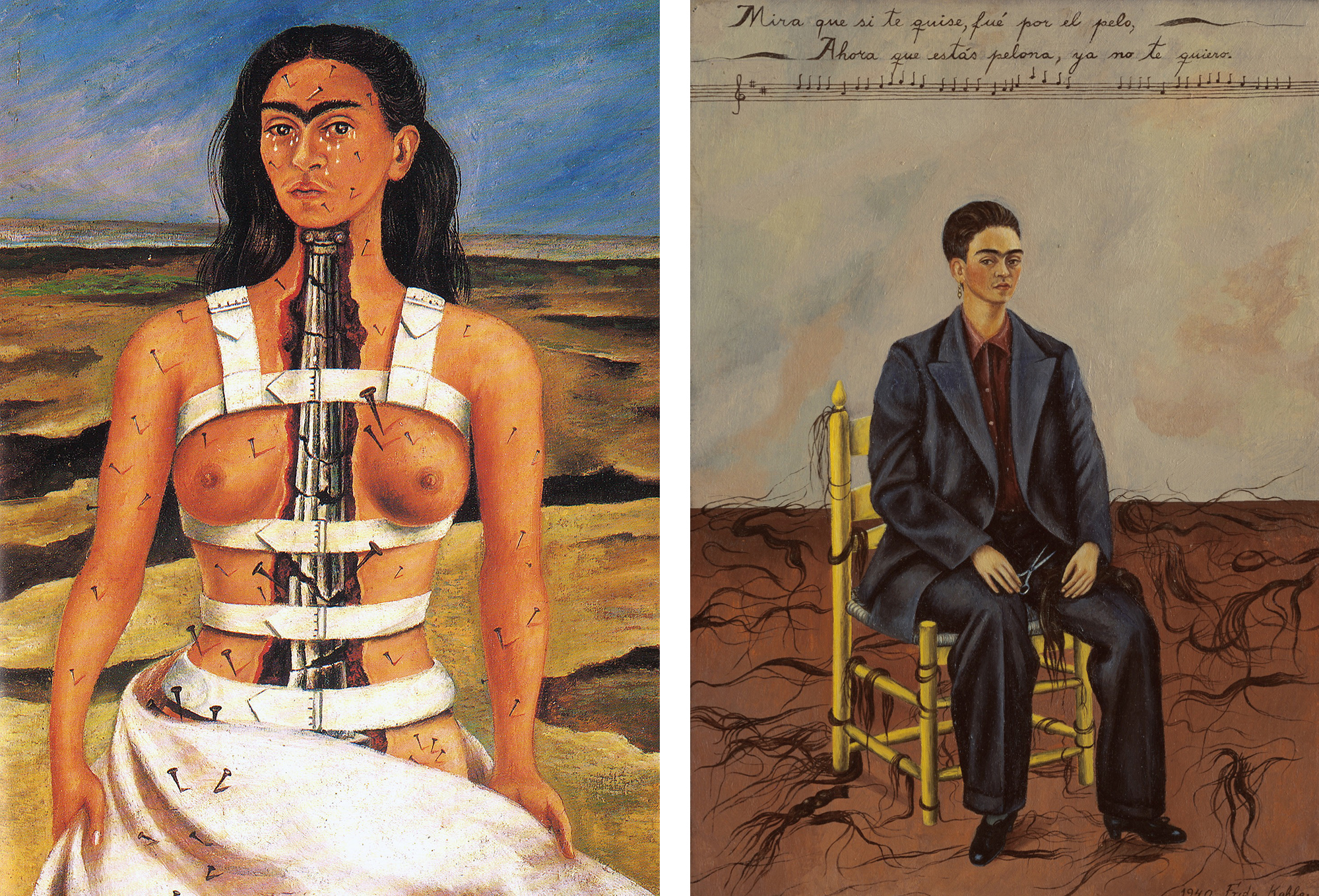

Women’s self-representations

Self-portraiture was a more significant genre among Surrealist women artists than it was among the men, and several women artists associated with the group are particularly notable for the depth and complexity of their engagement with self-representation. The most famous of these is Frida Kahlo, whom the Surrealist leader André Breton saluted as a natural Surrealist, although she never considered herself a member of the movement. Kahlo used her own image as a primary subject, often combining it with symbolic objects and scenes that represent her thoughts, feelings, and memories. She was also concerned with constructing her image in life, dressing in men’s clothes, or more often in traditional regional Mexican costumes, as a means of proclaiming her identity.

Leonor Fini, who also never joined the group but was friends with many Surrealists and participated in Surrealist exhibitions, was similarly preoccupied with her own image in art and life. She appears in her paintings as a beautiful, dominating, and sensual woman, often surrounded by imagined figures and environments. The self-image in her paintings was not unlike the figure she presented in person. She wore dramatic costumes, and once received the Surrealists dressed in priest’s robes, clothing she found particularly erotic and transgressive.

Unlike Kahlo and Fini, Claude Cahun participated in a variety of Surrealist group activities in the 1930s. In addition to making Surrealist objects, she produced a series of photographic self-portraits in which she transformed herself radically from one image to the next, appearing in several wearing masks and costumed as a doll. The gender ambiguities in many of her self-portraits suggest an exploration of her own image that is concerned with both personal and social issues of identity.

The role of women in Surrealism was complex and contradictory. The movement both infantilized and empowered women, treated them as erotic objects and supported their sexual emancipation, subjected them to the male gaze and validated their own self images. Furthermore, it is important to note that while women were a minority within the Surrealist group, many more women artists achieved significant recognition in the context of Surrealism than in other major modern art movements.

Additional resources:

Read a short biography of Toyen at the National Galleries of Scotland

Read more about Dora Maar at the Tate London

Read more about Dorothea Tanning and see more of her work at the Dorothea Tanning Foundation

Read more about Remedios Varo at MoMA

Read more about Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair at MoMA

Man Ray, The Gift

by JOSH R. ROSE

Man Ray and The Gift

The American artist Man Ray (born Emanuel Radnitzky) arrived in Paris in 1921. Within a year, the artist had his first solo show at a Parisian gallery. Among the works he exhibited was one unlisted sculpture: the object, which he called The Gift, was an everyday flatiron with brass tacks glued in a column down its center. According to Man Ray in his autobiography Self-Portrait, the object was made quickly, in a bout of inspiration, the day of the gallery opening.

What do we make of Man Ray’s relatively simple, yet subversive act of presenting a modified household appliance as a work of art? The flatiron – intended to smooth wrinkles from fabric – has been rendered useless with the addition of a row of brass tacks. We are perhaps expected to react the way the store owner supposedly did when Man Ray purchased these items, by exclaiming, “But you’ll ruin the shirt if you put tacks there!”

Dada, or the nonsense of the everyday

Before arriving in Paris, Man Ray was associated with the New York Dada group, which included the artist Marcel Duchamp. As a loosely-affiliated group of like-minded artists, they were particularly interested in using humor and antagonism to question the definition of a work of art. Re-defining art was prevalent in Duchamp’s Readymades, such as his Bicycle Wheel, a sculpture made by conjoining a bicycle wheel and a stool, two utilitarian objects.

The Surrealist object

Although made in the spirit of Dada, Man Ray’s The Gift prefigured by several years a key artistic practice that would develop within the Surrealist movement: the “Surrealist object,” a type of three-dimensional art work that included found objects, modified objects, and sculpted objects.

The Surrealist object—one of many literary and visual practices in the movement—became prominent beginning in 1936, after its association with a series of extravagant international expositions organized in London and Paris. Surrealism had been first publicly announced in 1924, with the publication of André Breton’s first “Manifesto of Surrealism.” Stridently activist, Surrealists sought to release society from cultural constraints and the need to conform to social norms, which they felt curtailed people’s desires to live as they wished.

Function/Dysfunction

Of the many types of Surrealist objects that were produced, two important features are present in Man Ray’s The Gift. First, an everyday object has been changed so that its original function is denied. Indeed, the artist’s relatively simple addition of tacks transforms a useful device into a destructive one.

Second, Man Ray’s alteration gives a common object a symbolic function. The flatiron, associated with social expectations of propriety and middle-class values, becomes a subversive attack on social expectations. Even if Man Ray’s tack-lined iron is no longer used for pressing clothes, the object resonates with ruinous, violent possibilities.

Denial and destruction

While denial and destruction are qualities are not intrinsic to all Surrealist art, there are striking examples, like The Gift, that show Surrealists working with banal objects to question the viewer’s expectations, and force us to re-evaluate the function of those objects in our lives.

Wolfgang Paalen’s work from 1938, Articulated Cloud, an umbrella crafted from spongy foam, denies the object’s intended function by causing water to be absorbed rather than repelled. It also makes the umbrella rather useless for anyone seeking shelter from rain.

Another object by Man Ray—a metronome with a photograph of a woman’s open eye clipped to it—adds an ominous sense of relentless observation to an ordinary musician’s timing instrument. Man Ray’s title of the piece, Object to Be Destroyed, seems mysterious at first. But when we consider the psychological effects of such obsessive observation—and think about what kind of impulses such regulations might evoke – the artist’s title becomes easier to understand.

No longer a simple time-keeping device, Object To Be Destroyed summons feelings of irritation over being watched, and powerlessness in the face of endless time. There is no means to stop the cycle, except to destroy the object itself.

Don’t touch the art!

The violent implications of The Gift and other Surrealist objects by Man Ray came to fruition in 1957 when Object to Be Destroyed was lost during a Man Ray retrospective. Varying stories exist as to the fate of the sculpture. In his autobiography, Man Ray recounts that a group of students visited the exhibition and caused a scene, during which one of them walked off with the sculpture, and it was never seen again. Numerous historians, however, state that during the exhibition one of the students took the title literally and smashed it with a hammer.

Whether stolen or smashed, Object to Be Destroyed no longer existed. This compelled Man Ray to remake the sculpture, but he pointedly changed the title to Indestructible Object.

Additional Resources:

Andre Breton, First Manifesto of Surrealism, 1924

Man Ray; Prophet of the Avant-Garde, American Masters Series on PBS.org (September 17th, 2005)

Salvador Dalí

Salvador Dalí, The Persistence of Memory

by SAL KHAN and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Salvador Dalí, The Persistence of Memory, 1931 (MoMA)

Salvador Dalí, Metamorphosis of Narcissus

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Salvador Dalí, Metamorphosis of Narcissus, 1937, oil on canvas, 51.1 x 78.1 cm (Tate Modern, London)

The ancient source of this subject is Ovid’s Metamorphosis (Book 3, lines 339-507). It tells of Narcissus, who upon seeing his own image reflected in a pool, so falls in love that he cannot look away. Eventually he vanishes and in his place is a “sweet flower, gold and white, the white around the gold.”

Dalí’s poem, below, accompanied the painting when it was initially exhibited:

Narcissus,

in his immobility,

absorbed by his reflection with the digestive slowness of carnivorous plants,

becomes invisible.

There remains of him only the hallucinatingly white oval of his head,

his head again more tender,

his head, chrysalis of hidden biological designs,

his head held up by the tips of the water’s fingers,

at the tips of the fingers

of the insensate hand,

of the terrible hand,

of the mortal hand

of his own reflection.

When that head slits

when that head splits

when that head bursts,

it will be the flower,

the new Narcissus,

Gala – my Narcissus.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Alberto Giacometti, The Palace at 4 a.m.

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Alberto Giacometti, The Palace at 4 a.m., 1932 , wood, glass, wire and string (Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Meret Oppenheim, Object (Fur-covered cup, saucer, and spoon)

by JOSH R. ROSE

A Luncheon with Fur

The story behind the creation of Object, an ordinary cup, spoon, and saucer wrapped evocatively in gazelle fur, has been told so many times its importance in modernist history transcends the fact it might be apocryphal (of dubious authenticity). The twenty-two year old Basel-born artist, Meret Oppenheim, had been in Paris for four years when, one day, she was at a café with Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar. Oppenheim was wearing a brass bracelet covered in fur when Picasso and Maar, who were admiring it, proclaimed, “Almost anything can be covered in fur!” As Oppenheim’s tea grew cold, she jokingly asked the waiter for “more fur.” Inspiration struck—Oppenheim is said to have gone straight from the café to a store where she purchased the cup, saucer, and spoon used in this piece. This amusing story belies the importance of Object and the critical acclaim and public fascination that has elevated it to point where it has become the definitive surrealist object…ultimately to Oppenheim’s dismay.

What Is a Surrealist Object?

Oppenheim’s Object was created at a moment when sculpted objects and assemblages had become prominent features of Surrealist art practice. In 1937, British art critic Herbert Read emphasized that all Surrealist objects were representative of an idea and Salvador Dalí described some of them as “objects with symbolic function.” In other words, how might an otherwise typical, functional object be modified so it represents something deeply personal and poetic? How might it, in Freudian terms, resonate as a sublimation of internal desire and aspiration? Such physical manifestations of our internal psyches were indicative of a surreality, or the point in which external and internal realities united, as described by André Breton (one of Surrealism’s founders and theorists) in his first Manifesto of Surrealism.

Visceral Responses

What, then, do we make of this set of be-furred tableware? Interpretations vary wildly. The art historian Whitney Chadwick has described it as linked to the Surrealist’s love of alchemical transformation by turning cool, smooth ceramic and metal into something warm and bristley, while many scholars have noted the fetishistic qualities of the fur-lined set—as the fur imbues these functional, hand-held objects with sexual connotations.

In a 1936 issue of the New Yorker Magazine, it was reported that a woman fainted “right in front of the fur-bearing cup and saucer [while it was on exhibit at MoMA]. “She left no name with the attendants who revived her – only a vague feeling of apprehension."\(^{1}\) Such visceral reactions to Oppenheim’s sculpture come closest, perhaps, to what were likely the artist’s aspirations. In an interview later in life, Oppenheim described her creations as “not an illustration of an idea, but the thing itself.”

Unlike Read and Dalí, Oppenheim stresses the physicality of Object, reinforcing the way we can readily imagine the feeling of the fur while drinking from the cup, and using the saucer and spoon. The frisson we experience when china is unexpectedly wrapped in fur is based on our familiarity with both, and the fur requires us to extend our sensory experiences to fully appreciate the work. Object insists we imagine what sipping warm tea from this cup feels like, how the bristles would feel upon our lips. With Oppenheim’s elegant creation, how we understand those visceral memories, how we create metaphors and symbols out of this act of tactile extension, is entirely open to interpretation by each individual, which is, in many ways, the whole point of Surrealism itself.

Presentation Problems

In spite of our individual response, the interpretation of Object has been complicated by the ways it was assigned meaning by others. When Object was finished, Oppenheim submitted it to Breton for an exhibition of Surrealist objects at the Charles Ratton Gallery in Paris in 1936. However, while Oppenheim preferred a non-descriptive title, Breton took the liberty of titling the piece Le Déjeneur en fourrure, or Luncheon in Fur. This title is a play on two nineteenth-century works: Édouard Manet’s infamous modernist painting Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeneur sur l’herbe) and Leopold von Sacher-Masoch’s erotic novel Venus in Furs. With these two references, Breton forces an explicit sexualized meaning onto Object. Recall that the original inspiration for this work was implicitly practical: when Oppenheim asked the waiter for more fur for her cooling teacup, it was suggested as a way to keep her tea warm, and not necessarily as overtly sexual.

The Meaning of Others

Certainly we cannot assume that the spark of the idea for this piece and the piece itself are necessarily related, but the way meanings have been ascribed to Oppenheim’s pieces by others has plagued many of her works.

Art historian Edward Powers has noted that when Oppenheim sent her Surrealist object Das Paar to a photographer before submitting it for exhibition, the photographer took the liberty of tying up the laces before photographing it. When Breton saw the photo with tied laces, he dubbed this object à délacer which in French means to untie, typically either shoes or a corset. The title and laced shoes together suggest the potential act of undressing and a fascination with exposing the female body. However, when Oppenheim later described Das Paar (with the laces untied), she stated it was an “odd unisexual pair: two shoes, unobserved at night, doing ‘forbidden’ things.” She expressly assigned no gender, and suggests the “forbidden” acts already taking place between anthropomorphized shoes. She takes a more literal approach, the shoes as expressive things in themselves, rather than symbolically resonant of something else.

This is not to suggest that all her interactions with Breton were negative. When she happened across a wonderfully disturbing photograph of a bicycle seat covered in bees, she mailed it to Breton, who republished the found photograph as an artistic contribution by Oppenheim in the third issue of the new Surrealist publication Medium.

Dangerous Success

Yet, the early acclaim for the fur-covered Object had a negative effect on Oppenheim’s early career. When it was purchased by The Museum of Modern Art and featured in their influential 1936-37 exhibition “Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism,” visitors declared it the “quintessential” Surrealist object. And that is how it has been seen ever since. But for Oppenheim, the prestige and focus on this one object proved too much, and she spent more than a decade out of the artistic limelight, destroying much of the work she produced during that period. It was only later when she re-emerged, and began publicly showing new paintings and objects with renewed vigor and confidence, that she began reclaiming some of the intent of her work. When she was given an award for her work by the City of Basel, she touched upon this in her acceptance speech: “I think it is the duty of a woman to lead a life that expresses her disbelief in the validity of the taboos that have been imposed upon her kind for thousands of years. Nobody will give you freedom; you have to take it.”

1. Nelson Landsdale and St. Clair McKelway, Talk of the Town, “Critical Note,” The New Yorker, December 26, 1936, p. 7.