8.10: Symbolism / Art Nouveau

- Page ID

- 75186

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Symbolism and Art Nouveau

Many artists in the late 19th century broke from naturalistic representation and sought visual equivalents to poetry and music.

c. 1880 - 1910

Art Nouveau

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

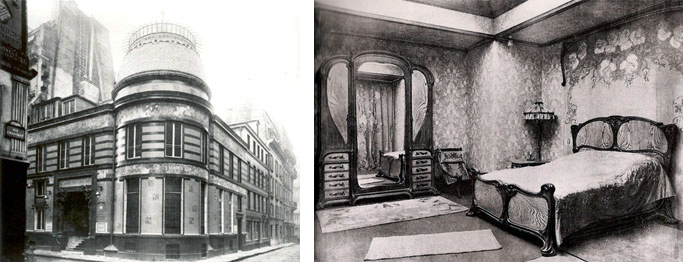

Victor Horta’s Tassel House in Brussels is one of the earliest examples of the Art Nouveau style. Horta designed the building’s architecture and every detail of the interior decoration and furnishings, making the house into a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total art work in multiple media. The repeated use of organically curved, undulating lines — often called whiplash lines — unifies the design, repeating in the floor tiles, wall painting, ironwork, and even in the structure of the spiraling staircase and surging entryways.

A modern style using modern materials

Art Nouveau artists and designers created a completely new style of decoration, rejecting the widespread nineteenth-century practice of copying historical, and especially Classical and Medieval, forms. While each designer invented their own decorative motifs, organic, often plant-based, forms and the whiplash line became hallmarks of Art Nouveau design, appearing in multiple media and contexts.

Art Nouveau architects and designers also embraced modern building materials, notably cast iron. Cast iron is both stronger and more flexible than traditional wood or stone and allows for much thinner supports, like the slender columns in Horta’s own house. Iron support structures also made it possible to create curved facades with large windows, which became prominent elements in many Art Nouveau buildings, including Horta’s Maison du Peuple.

An international style

Art Nouveau is only one of many names given to this international fin-de-siècle style, which had many regional variations. The term (French for “New Art”) derives from La Maison de L’Art Nouveau, the Paris art gallery run by Siegfried Bing, who was a major promoter of the new style, as well as of Japonisme and the Nabis. In addition to marketing individual objects, Bing commissioned artists and designers to create model rooms in his gallery to display Art Nouveau ensembles that included furniture, wallpaper, carpets, and paintings.

In addition to Paris, major centers of the modern fin-de-siècle style included Brussels, Glasgow, Munich (where it was known as Jugendstil or Youth Style), and Vienna (where it was called Secession Style). Barcelona’s Catalan Modernism, especially Antoní Gaudí‘s architecture and decorative designs, is also closely related to Art Nouveau.

Luxury design for the masses

French Art Nouveau was linked to government-supported efforts to expand the decorative arts and associated craft industries. Private residences and luxury objects were the focus for many Art Nouveau designers, including Emile Gallé, who made both decorative glass and furniture. Despite the close association of Art Nouveau with luxury items, the style is also apparent in urban design, public buildings, and art for the masses. Horta’s Maison du Peuple was the center for the socialist Belgian Workers’ Party, and among the most famous examples of Art Nouveau style are Hector Guimard’s entrances to the Paris Metro, the city’s new public transportation system.

Like Horta’s designs for the Tassel House, Guimard used cast iron and invented stylized motifs based on plant forms. Industrially fabricated in modular units, the cast iron was relatively cheap, but it was painted green to resemble oxidized copper, a much more expensive material that adds a sense of luxury to the elaborate entrances. The use of modules made it possible to individualize each station while maintaining stylistic unity throughout the city.

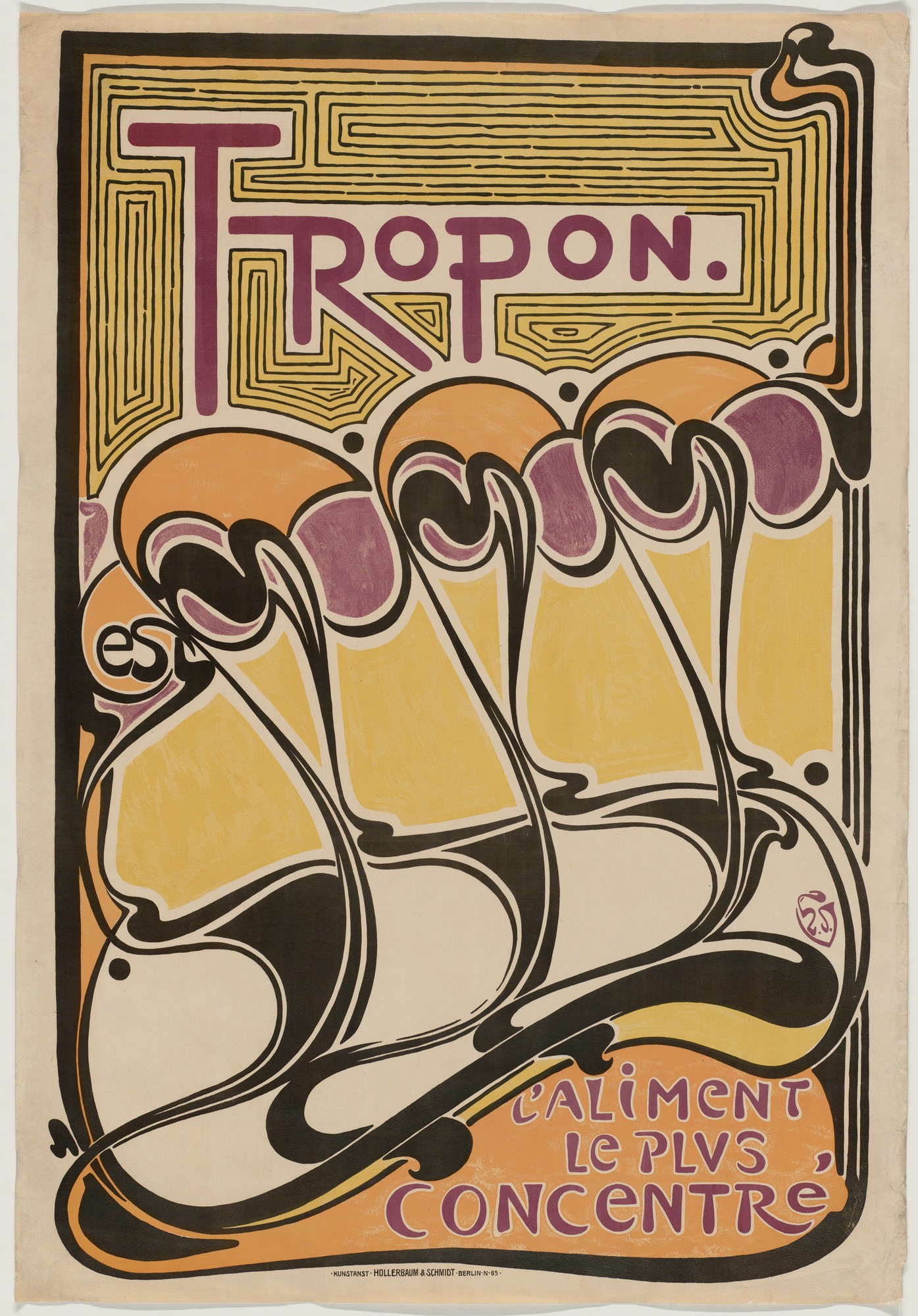

Art Nouveau designs were also widely visible in the advertising posters that decorated Paris. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Alphonse Mucha, and Jules Chéret depicted famous fin-de-siècle performers such as Jane Avril, Sarah Bernhardt, and Loïe Fuller. Their posters stylized the female body and used sinuous whiplash lines, decorative plant forms, and flattened abstract shapes to create vivid decorative images.

In a poster for the nutritional supplement Tropon, Henry van de Velde explored the decorative and suggestive potential of non-representational forms, using the whiplash line to create an abstract design of organic shapes that suggest both plant-like growth and dancing figures in the rising diagonal of repeated forms.

A holistic approach

Van de Velde worked in many different media, designing buildings, interiors, furniture, and decorative objects as well as posters. In the Continental Havana Company building in Berlin he used sinuous curves to integrate the shelving, doorways, alcoves, furniture, and walls into a unified organic whole.

The English designer William Morris and the English Arts and Crafts Movement that he initiated were a key influence on van de Velde and many other designers associated with Art Nouveau. Morris promoted a holistic approach to interior decoration as well as advocating for the social importance of design and high quality craftwork. In 1907 van de Velde founded the School of Arts and Crafts in Weimar, Germany, which promoted similar values. It later became the famous modern art and design school, the Bauhaus, which maintained the tradition of integrating art, craft, and design for the improvement of society.

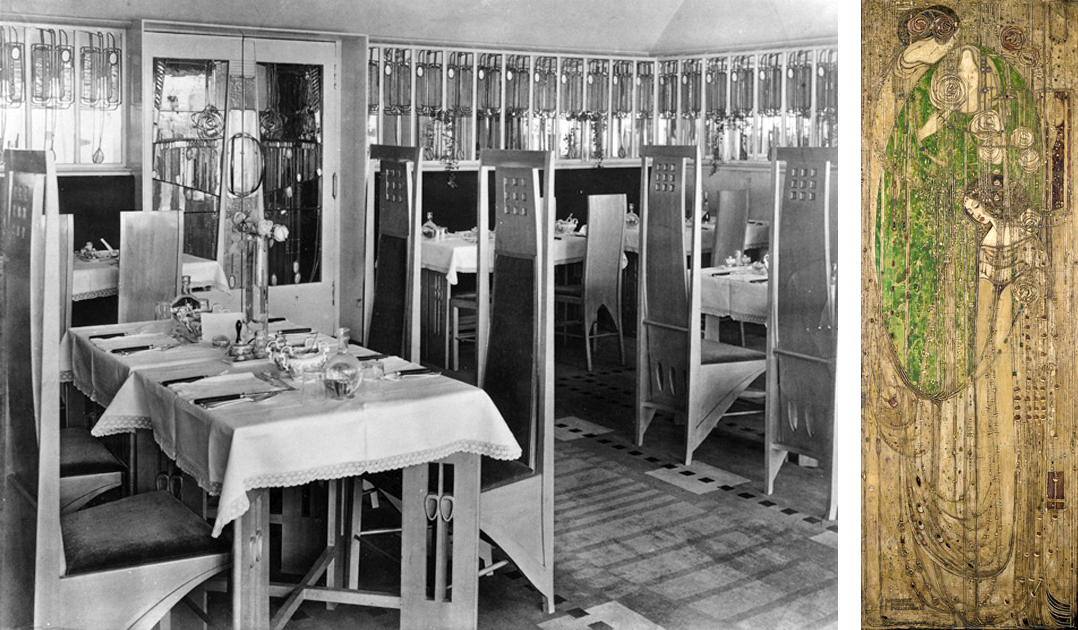

Glasgow style

Curving whiplash lines are a common characteristic of French and Belgian Art Nouveau, but architects and artists working in Glasgow developed a more rectilinear style exemplified by the Willow Tea Room. Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald designed every component of the tea room, including the architecture, stained glass, decorative panels, furniture, cutlery, and staff uniforms. In keeping with Art Nouveau artists elsewhere they developed original stylized design motifs based on plant forms, but theirs were rigidly contained within elongated rectangles rather than expanding into supple curves.

Vienna Secession style

The Viennese Secession style also combined strict geometric forms with stylized organic decoration. Like Guimard’s entrances to the Paris Metro, Otto Wagner’s stations for Vienna’s public transportation system displayed the city’s modernity and wealth in their iron construction and their luxurious gold sunflower-motif decoration.

Joseph Maria Olbrich’s Secession Building proclaimed the goals of the rebellious group of artists who seceded from the Austrian art establishment in order to embrace avant-garde modern art. They displayed their work inside Olbrich’s building as well as hosting international exhibitions of modern art. The stylized decoration of the building is based on plant forms, while the structure emphasizes the harmonious balance of basic geometric shapes.

The leader of the Vienna Secession, Gustav Klimt, decorated the interior walls of the main exhibition hall with a long decorative mural dedicated to Ludwig von Beethoven. The Beethoven Frieze combines naturalistic representation of the human body, stylized figures, and complex abstract patterns in a variety of materials. Gold leaf and semi-precious stones enhance the decorative quality of the surface, making it a dramatic union of luxurious ornament and figurative painting.

Art Nouveau was fashionable for only a brief period around the year 1900, but the movement was part of a long-term modern trend that rejected historicism and Academicism and embraced new materials and original forms. In the modern period artists and designers increasingly recognized that the health and well-being of society and all its members were supported and enhanced by well-designed objects, buildings, and spaces. The unified designs of Art Nouveau presaged the innovations of the Bauhaus as well as architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier.

The Nabis and Symbolism

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

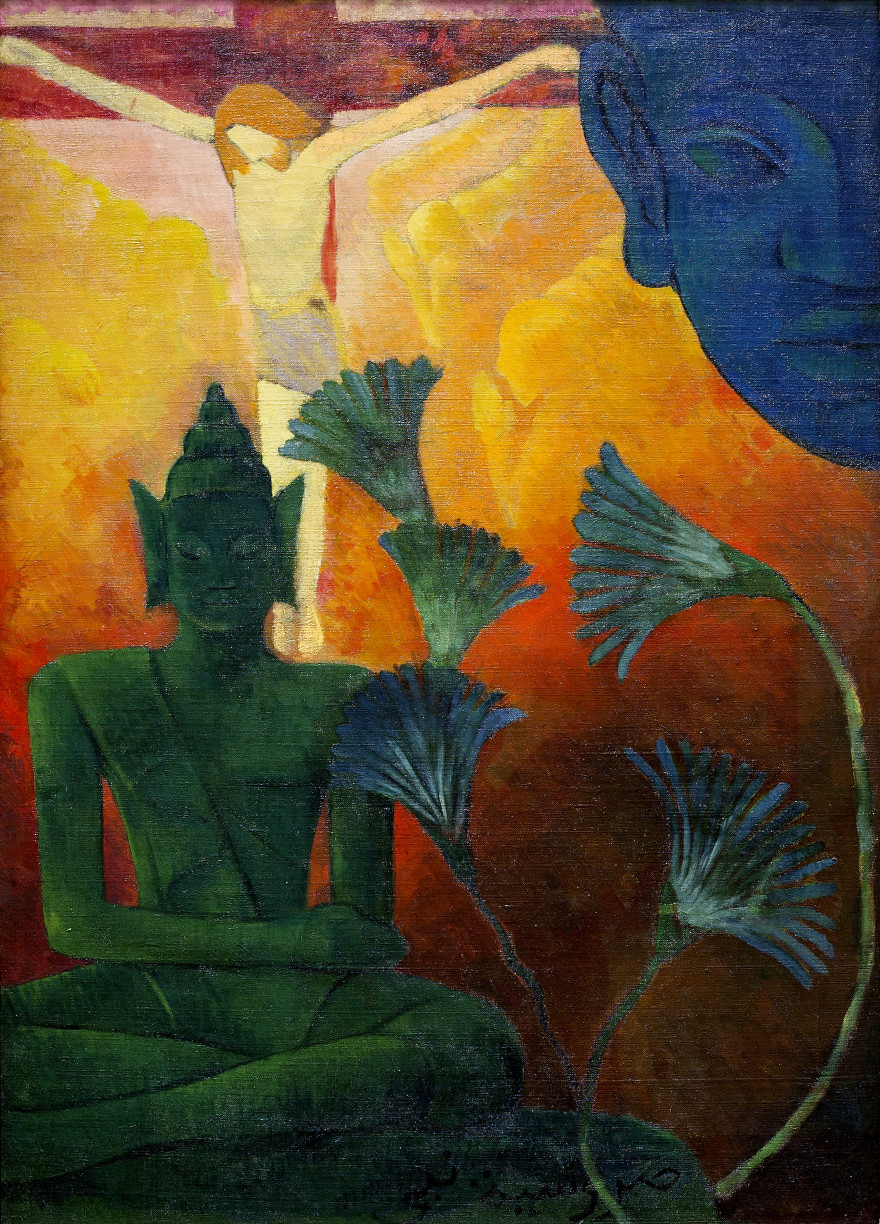

In the fall of 1888 Paul Sérusier spent an afternoon with Paul Gauguin in Brittany painting a small landscape on a cigar box lid. He followed Gauguin’s instructions to emphasize the colors he saw by using paint directly from the tube with little or no mixing. The result was a patchwork design of vivid colors only vaguely suggestive of its subject, trees on a riverbank.

Later in Paris Sérusier showed the landscape to fellow art students at the Académie Julian who saw it as an artistic revelation. They named the painting “The Talisman” and formed a group called the Nabis, after the Hebrew word for prophet. In addition to Sérusier the group included Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, Paul Ranson, and Ker-Xavier Roussel, as well as others. In the 1890s the Nabis were one of the most innovative Post-Impressionist groups working in Paris.

Spiritual concerns

Like Gauguin and many other artists of the period, the Nabis were engaged with the spiritual and mystical concerns associated with fin-de-siècle Symbolism. Sérusier’s Portrait of Paul Ranson in Nabi Costume documents their early interest in esoterica and occult ceremonies. The simplified style Sérusier used derived from Gauguin’s Synthetism but was only one of the styles associated with Symbolism. It forms a marked contrast to the academic naturalism used by many fin-de-siècle Symbolist painters such as Jean Delville, who depicted the Symbolist writer Joséphin Péladan in robes and accompanied by ceremonial objects and symbols, much as Sérusier portrayed Paul Ranson.

A widespread attitude

Symbolism began as a literary movement with the 1886 publication of Jean Moréas’ Symbolist manifesto in the Paris newspaper Le Figaro. It quickly became a kind of catch-all term for a widespread fin-de-siècle aesthetic attitude that embraced the spiritual significance of art while rejecting science and objectivity. Symbolist artists favored idealism over realism, suggestion over specificity, and subjective expression over objective representation. They employed a variety of styles and approaches, including both traditional naturalism and modern techniques associated with Post-Impressionism. Many of the painters who exhibited at the popular Symbolist Salon of the Rose + Cross organized by Péladan in the 1890s favored a highly-detailed naturalism. These included Delville and Fernand Khnopff, whose dream-like images became prominent examples of Symbolist art.

Conveying meaning through color and design

Nabi painters used the modern Synthetist style of Gauguin, which emphasized abstract form, to convey spiritual meaning as well as a means of suggestion and personal expression. Maurice Denis was the most prominent art theorist associated with the Nabis, and one of his early statements became a famous touchstone of formalist modernism: “A painting — before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote — is essentially a flat surface covered with colors arranged in a certain order.”[1] Emphasis on color and surface design is a primary characteristic of Nabi painting, which conveys emotion and meaning through abstract formal relations.

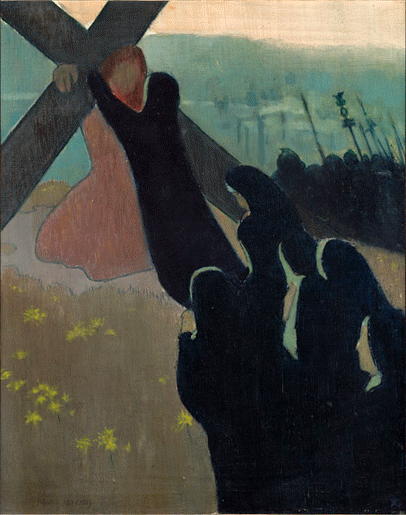

In Denis’ Climbing to Calvary the simple dark shapes of black-robed nuns rise diagonally towards a large cross carried by a barely-defined red Christ. One nun reaches out to embrace Christ at the top of the hill, and a strip of bright sky tops off the scene. The basic forms convey the combination of mourning and hope that Christians associate with Christ’s death and resurrection. The scene is timeless, containing elements of the present (the nuns) and the past (Mary embracing Christ on the way to the Crucifixion, the dark silhouette of a crowd of Roman soldiers over the hill). The figure of Christ suggests both the nuns’ spiritual vision of Christ carrying the cross, similar to Gauguin’s Vision after the Sermon, and a Good Friday procession re-enacting the Crucifixion.

Different approaches

A comparison of Denis’ painting with Carlos Schwabe’s Death and the Gravedigger shows two very different approaches to Symbolist painting. In Denis’ work, the forms are reduced and simplified to mostly flat color areas. Basic symbols, shapes and their relationships convey meaning: the Christian cross, black for mourning, red for the blood of sacrifice, the upward movement towards light and resurrection.

Schwabe uses similar compositional devices to convey the theme of death and resurrection; both paintings show darkness and symbolic death at the bottom of the painting, light and resurrection rise above. Unlike Denis, however, Schwabe employs a traditional naturalistic technique that records many details based on careful observation. The figures and location are so specific that they suggest the illustration of a particular scene in a story. Denis by contrast depicts a more generalized, anonymous image of death and Christian resurrection.

Symbolism without symbols

Symbolism is perhaps easiest to recognize in artworks that present known symbols, such as the Christian cross, or overtly symbolic meanings through recognizable themes such as youth, old age, love, death, etc. In addition to Denis’ Climbing to Calvary, many well-known Post-Impressionist works use conventional symbolism in this way, including Gauguin’s Vision after the Sermon. Symbolism was also, however, associated with both a conception of art as subjective expression and the capacity of art to suggest profound meanings indirectly. As a result, many artworks that lack obvious symbols or clear symbolic significance are also associated with Symbolism.

Pierre Bonnard was one of the founding members of the Nabi group. His painting Twilight (Game of Croquet) depicts men and women playing croquet surrounded by richly varied foliage. In the distance, women in long white dresses dance on the grass. The style is typical of Nabi painting with its flat simplified forms and emphasis on surface design. The leaves of the various plants, the printed fabrics of the women’s dresses, the man’s plaid jacket, and the dog’s white and brown fur create a decorative surface of multiple textures and patterns.

A Symbolist mood

Although Twilight depicts an ordinary leisure activity (a typical subject of Impressionist painting), the mood is melancholy and dream-like, in keeping with Symbolist attitudes. The foreground figures are introspective and almost lost in the foliage, while the women in the background are otherworldly white figures dancing in the dusky light. The mysterious dream-like quality is typical of much Symbolist painting regardless of its style.

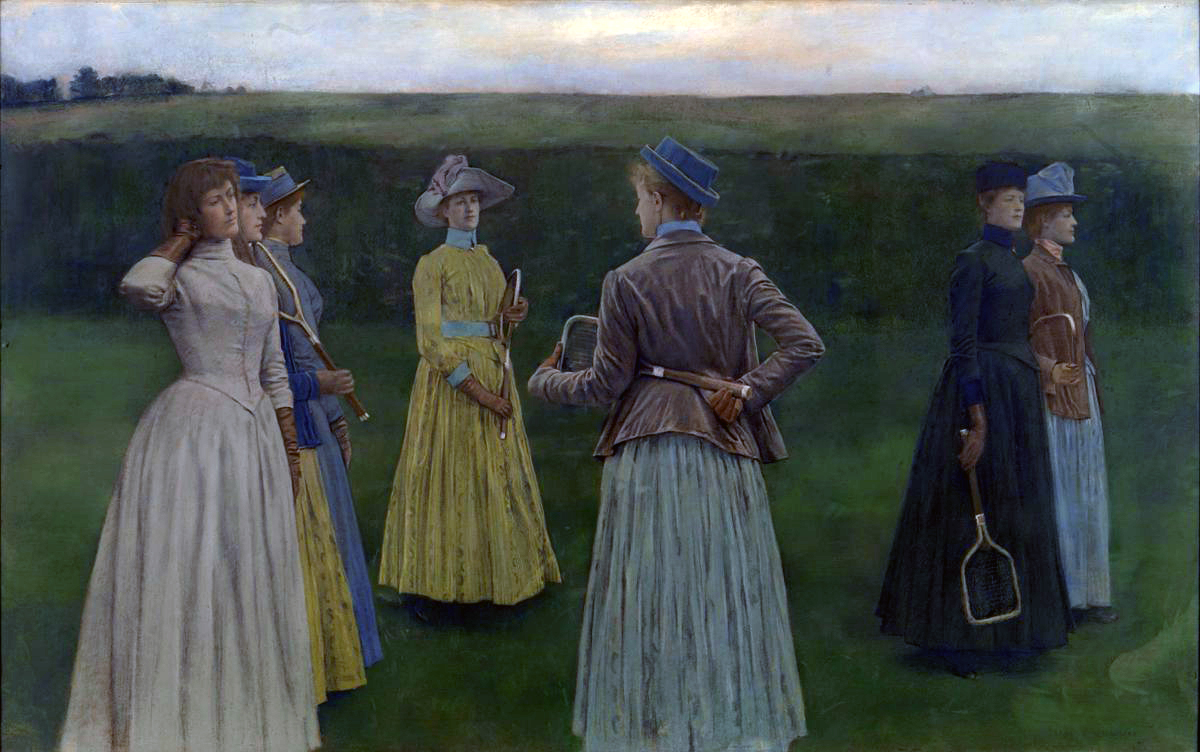

A comparable Symbolist work in a more traditional naturalistic style is Fernand Khnopff’s Memories, in which several women holding racquets stand on a lawn seemingly lost in thought. Both Bonnard and Khnopff turn an ordinary modern subject into an image that suggests greater depth and significance without specifying any particular meaning.

The subjects of Nabi paintings varied from the overt, often religious, symbolism of Maurice Denis to scenes of contemporary urban and suburban life depicted by Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard. Whatever their subject, though, the Nabis relied on the formal qualities of color, pattern, and surface design to enhance the dreamy moods and profound meanings of Symbolist art. Their emphasis on the capacity of formal elements to convey meaning and emotion was an early contribution to the developments that led to abstract art.

Notes:

- Maurice Denis, “Definition of neo-traditionism” (1890), in Jean-Paul Bouillon, ed., Le Ciel et l’arcadie (Paris: Hermann, 1993), p. 5 (authors’ translation).

Additional resources:

Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris, 1892–1897 at the Guggenheim Museum

Review of Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris, 1892–1897 at Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide

Read more about Symbolism at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn timeline of Art History

The Nabis and Decorative Art

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

In 1894 the Nabi painter Édouard Vuillard decorated the living room of a Paris mansion with nine paintings depicting children and their nannies in the park. The three panels shown here form a symmetrical group in the traditional triptych format of an altarpiece, with two tall vertical panels framing a wider central panel. They present a single continuous view connected by a horizontal fence and distant forest.

In the foreground the composition is strongly asymmetrical, with most of the figures crammed into the left panel. Diagonals created by the painted patterns of light and shade on the ground enhance the dynamic asymmetry of the painting. The people form points of interest surrounding the empty expanse of sandy gravel in the center. Variegated patterns of foliage, clothing, and clouds are scattered across the paintings’ surfaces, while patches of flat color punctuate the composition and serve as visual anchors.

Abstract decorative forms

Vuillard’s emphasis on flat patterns and design is typical of Nabi painters, who embraced the implications of Maurice Denis’ statement: “A painting — before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote — is essentially a flat surface covered with colors arranged in a certain order.”[1] Nabi paintings do not allow viewers to get lost in the represented scene and forget that they are looking at colors applied to a surface. Instead, they display the tension between the represented scene and the paint that creates it by emphasizing abstract decorative forms over naturalistic details.

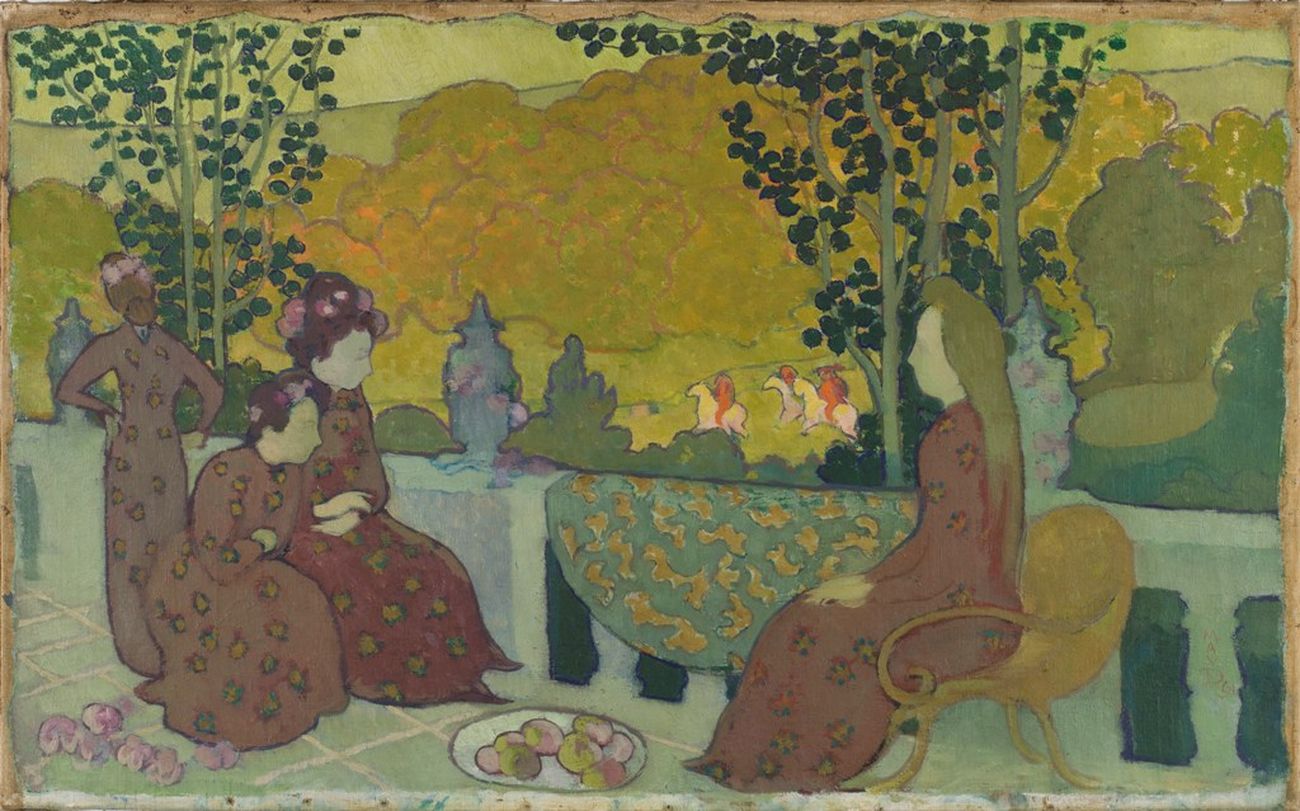

In Maurice Denis’ April the landscape and figures are reduced to simple shapes, and the colors are flat and unmodulated. Denis further emphasizes the surface of the picture plane by depicting the distant hills in red tones rather than fading blues to represent the effect of atmospheric perspective.

A decorative arts tradition

April was made specifically to decorate a young girl’s room, and many Nabi paintings were designed as ensembles for specific locations. The seven-foot-tall panels of Vuillard’s Public Gardens created a wallpaper-like backdrop for a family’s living room. This integration of representational paintings into the decorative scheme of a room was markedly different from the conventional manner of framing paintings as if they were windows onto another world.

In embracing decorative painting the Nabis were participating in a well-established French tradition of decorative arts and luxurious artisanal production. During the eighteenth century Rococo paintings were designed as components of multi-media decorative ensembles for aristocratic salons, such as the Salon de la Princesse in the Hôtel de Soubise. In the nineteenth century the most prominent decorative paintings were murals in public buildings. The classicizing public murals of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes were admired by the Nabis as well as by many other Post-Impressionist and Symbolist artists.

They appreciated the suggestive qualities of Puvis’ dream-like images of introspective figures as well as his simplified forms and colors. Puvis’ limited range of muted pastel colors imitated the qualities of Italian Renaissance frescoes, and enhanced the flat decorative qualities of his paintings by softening contrasts and eliminating details. The Nabi painters adapted Puvis’ decorative approach to modern subject matter and used painting techniques that reflected the innovations of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in their bright colors, visible brushwork, and surface patterns.

The influence of Japanese art

The Nabis were also greatly influenced by Japanese art and design in their compositions as well as in their engagement with the decorative arts. Pierre Bonnard used the popular Japanese format of multi-panel folding screens for a number of works, including Nannies’ Promenade.

Like Vuillard’s Public Gardens, Bonnard’s screen is both representational and decorative. The subject of the works is similar, a modern scene of nannies and children, and in both works the asymmetrical composition spreads across several panels with the overall emphasis on flat patterns and ornamental design.

Designing for life

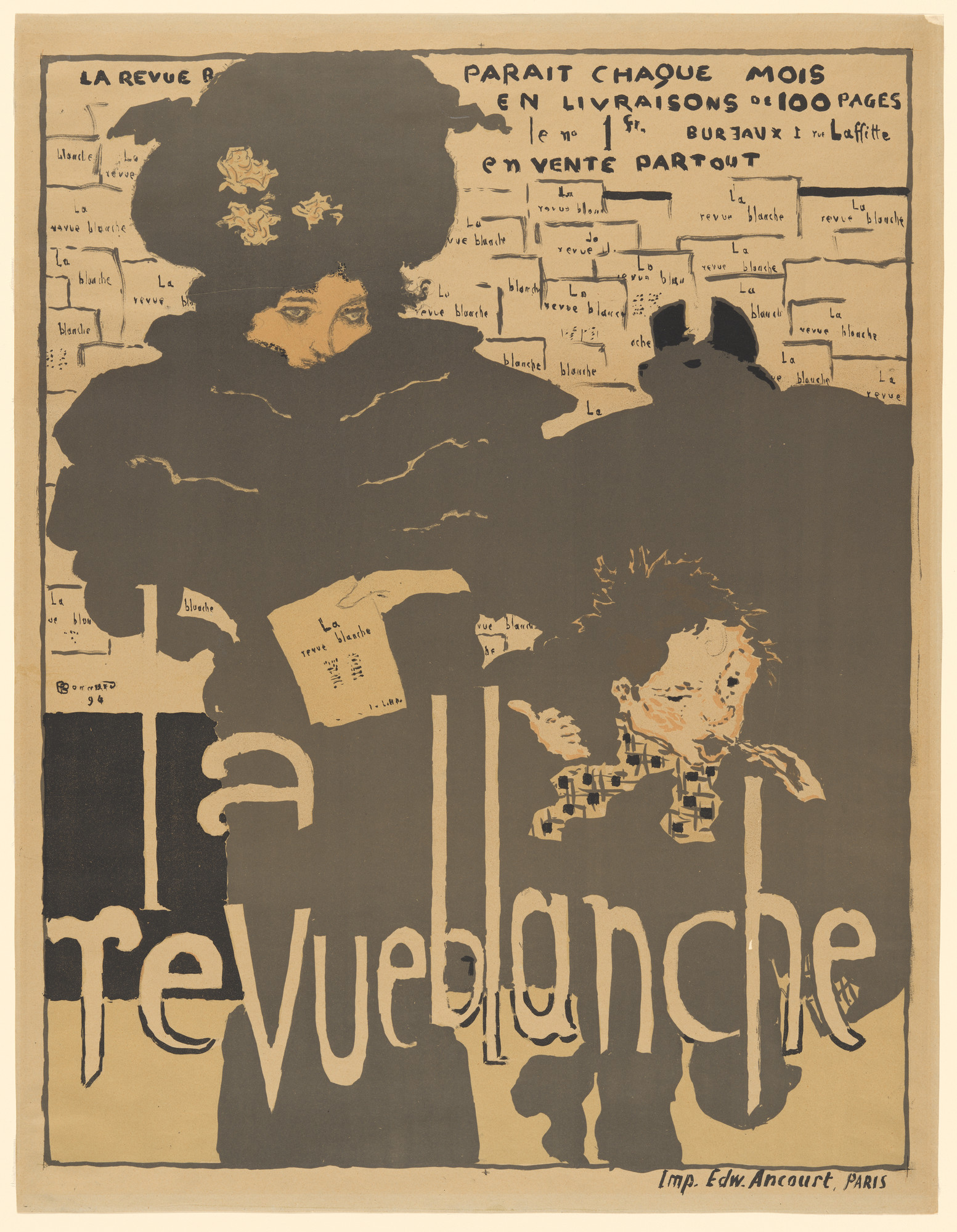

The Nabis’ embrace of the decorative arts was wide-ranging and included designs for wallpaper, tapestries, stained glass, and ceramics. They illustrated books, created posters, and designed costumes and sets for Symbolist theatrical productions. Pierre Bonnard’s poster for the Symbolist literary journal La Revue Blanche adapts the Nabi style of flat patterns and decorative design to the print medium of color lithography.

Through their many forms of artistic production the Nabis expanded art into all areas of life. This was a widely-shared goal among fin-de-siècle artists and designers, particularly those involved with the international movement known in France as Art Nouveau.

The Nabis were closely associated with Art Nouveau through the art dealer Siegfried Bing, a leading promoter of both Art Nouveau and Japonisme. Bing exhibited Nabi art in his Paris gallery and commissioned work from them, including designs for stained glass windows to be made by Louis Comfort Tiffany’s American company.

The Nabis exhibited as a group through the 1890s. Their formalist approach to painting influenced many later modern painters, most notably the Fauves in the early 1900s. The Nabis also contributed to modernism’s breakdown of the traditional value distinctions between the fine and decorative arts. Their wide-ranging work in a variety of media was part of a trend in art and design that encompasses the Arts and Crafts Movement and Art Nouveau in the nineteenth century and Russian Constructivism and the Bauhaus in the twentieth century.

Notes:

- Maurice Denis, “Definition of neo-traditionism” (1890), in Jean-Paul Bouillon, ed., Le Ciel et l’arcadie (Paris: Hermann, 1993), p. 5 (authors’ translation).

Additional resources:

“The Nabis and Decoration,” 2019 exhibition at the Grand Palais, Paris (video in French with English subtitles available)

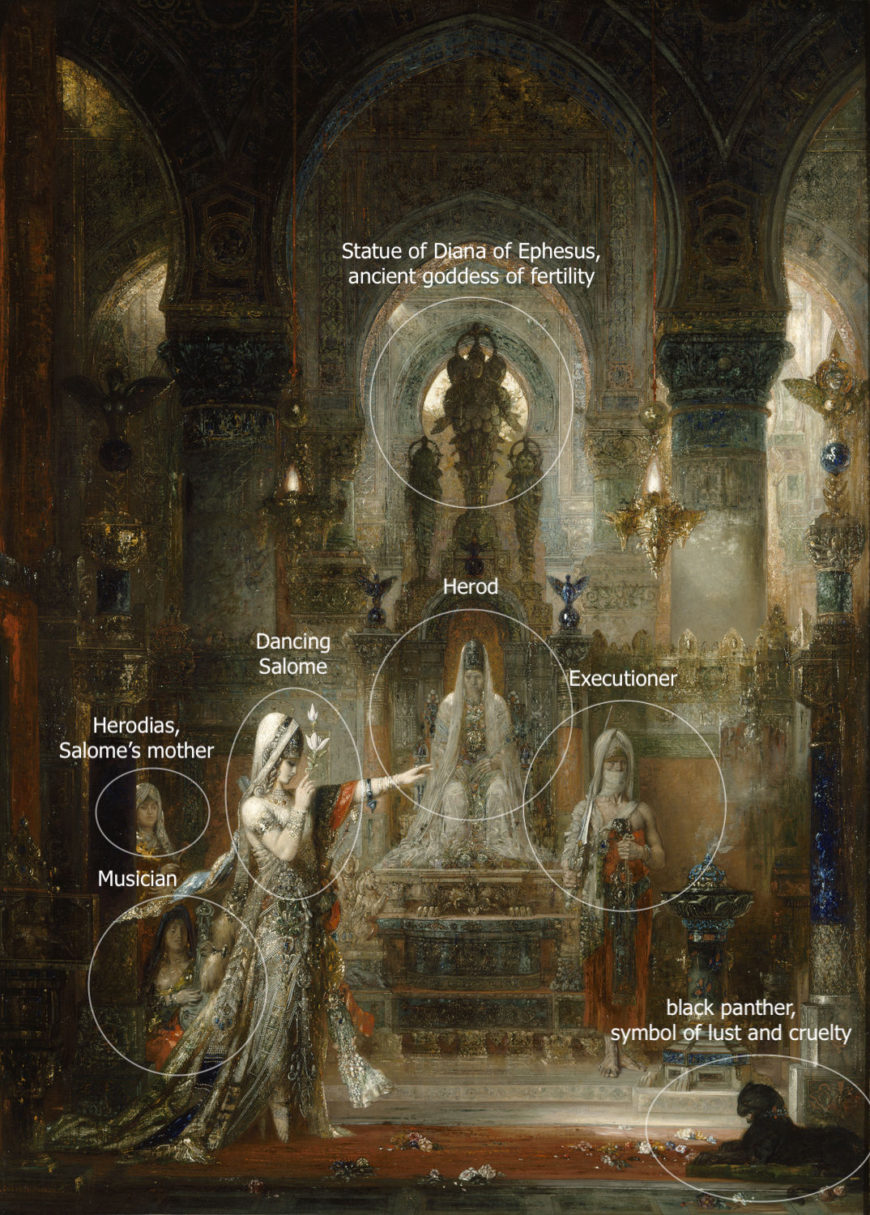

Gustave Moreau, Salome

by DR. VASILE-OVIDIU PREJMEREAN

Salome dancing before Herod, with its bewildering subject matter and lush colors, is without a doubt one of the most remarkable paintings of the nineteenth century.

The painting was first exhibited at the 1876 Salon (and shortly thereafter at the 1878 World’s Fair), along with The Apparition, Hercules and the Lernaean Hydra and Saint Sebastian Baptized a Martyr — all works by the French symbolist and history painter Gustave Moreau.

Alongside these other paintings, Salome shows not only Moreau’s preference for religious, literary, and mythological subjects, but also his desire to picture the struggle between “spirit” and “matter”—a subject Moreau pursued his entire career.

The theme of Salome is one that Moreau returned to time and again. The artist explored the subject in more than one hundred sketches and drawings as well as in numerous paintings—ranging from highly elaborate to sketchily rendered—and even in sculpture (both Salome and The Apparition figured in Moreau’s waxworks). Moreau was not alone in his passion for the theme of Salome, as other famous artists — Lucas Cranach, Caravaggio, Titian, Guido Reni, Artemisia Gentileschi, Aubrey Beardsley, and Nabil Kanso, to name just a few — shared this interest. Salome is the woman whose dance led to the demise of John the Baptist.

In the New Testament, both Matthew (14:1-11) and Mark (6:14-29) tell of the famous banquet story in which Herodias, having grown angry at John the Baptist for saying she could not marry her ex-husband’s brother, asks her daughter to request John’s head from her half-uncle as payment for her dance. Although neither of these sources mention Salome by name, we can learn of her from Flavius Josephus’ Jewish Antiquities of the year 93-94 (Book XVIII, Chapter 5, 4).

Given the scarcity of texts, and the fact that Salome seems not to know what to ask her uncle for until instructed by her mother, it is unclear if Salome is truly the evil temptress she is supposed to embody, or just an unwitting instrument in her mother’s hands.

Salome’s complex and ambiguous story offered vast artistic freedom [1]. It is no wonder that Moreau refers to her as “My Salome.” [2] In his writings, Moreau underlines the sacredness of the scene, but also warns of the proverbial power of the femme fatale (a seductive woman who lures men into dangerous situations—a popular subject among Symbolist artists) as one who can be fatal to any man—even saints. [3] Moreau’s contemporaneous viewers also focused on Salome as “femme fatale” (perhaps most famously, the Symbolist novelist and art critic J. K. Huysmans in his novel À rebours).

This skewed interpretation shaped painters’ imagination for generations. Moreau makes clear that his goal in turning to Salome as subject, was to reinvigorate high art through beauty and idealism [4]. Of course, not every painter had the same lofty goals, as Henri Regnault’s version makes plain, given its orientalist depiction and lush representation of Salome and her surroundings. Regnault’s 1870 Salome played an important role in Moreau’s decision to tackle the subject, as he wanted to show the world a different rendering of the subject, rooted not in orientalism and the straightforward depiction of a femme fatale, but in mystery, eclecticism, and the “archeology of sentiment and imagination,” which he attributed to Rembrandt. [5]

Given the interest Moreau paid to the Dutch master’s subjects and technique during the 1870s, it is no wonder that much of Remdrandt’s treatment of light and darkness as well as his rich colors find new life in Moreau’s painting.

As scholars Peter Cooke and Julius Kaplan pointed out, Moreau had multiple sources from which he could have drawn inspiration, such as Rembrandt’s Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple and Ingres’ Antiochus and Stratonice for the architectural structuring of the painting’s composition; Jacques Louis David’s The Oath of the Horatii for Salome’s uncharacteristically theatrical gesture of her left hand; Giovanni Bellini’s San Zaccaria Altarpiece for the character’s self-absorbed pose; and Delacroix’s Jewish Wedding in Morocco, where we encounter a dance pose similar to that of Moreau’s Salome. Anti-theatricality constituted a constant in Moreau’s oeuvre as he preferred immobile, somnolent figures to vividly animated ones.

If we look closely, we notice that Salome doesn’t really dance [6]; instead, she appears to hover, as though she belonged to a magical realm. The dissonance between her “inward” gaze and the unnatural position of her arms further enhances this perception, as does the lotus flower she holds upright. Its symbolism is ambiguous. Does it signal lust, or is it a symbol of purity? Moreau’s typically enigmatic approach made him a target for the promoters of Naturalism, most notably Émile Zola, who accused him of retreating into his dreams and offering an artistic response to the challenge posed by science—one that couldn’t possibly have value in the modern age. Such criticism hurt him deeply and only fueled Moreau’s purposeful cultivation of ambiguity.

As viewers, we are aligned to mirror Herod as he sits, seemingly transfixed, his passivity underlined by the majestic statue of Diana of Ephesus—an ancient goddess of fertility —that towers above him. It is not only Herod who mirrors the voyeuristic role of the viewer; the musician on the left, Herodias behind him, glance towards Salome’s face or her upraised left arm. Only the executioner looks elsewhere.

The black panther in the foreground, a symbol of lust and cruelty, looks down forward and implicitly submits to the otherworldly will of the dancing Salome. If Salome the woman dazzles the viewer through her beauty and pose, Moreau’s depiction of Salome does so not only through the glittering colors, but also through the marvelous abundance of detail, that scatter our gaze and prompts us to admire the. wealth of carefully crafted minutia we are offered. Some critics, contemporaneous with Moreau, like Georges Lafenestre, were enchanted and baffled by the sheer abundance of details in his paintings.

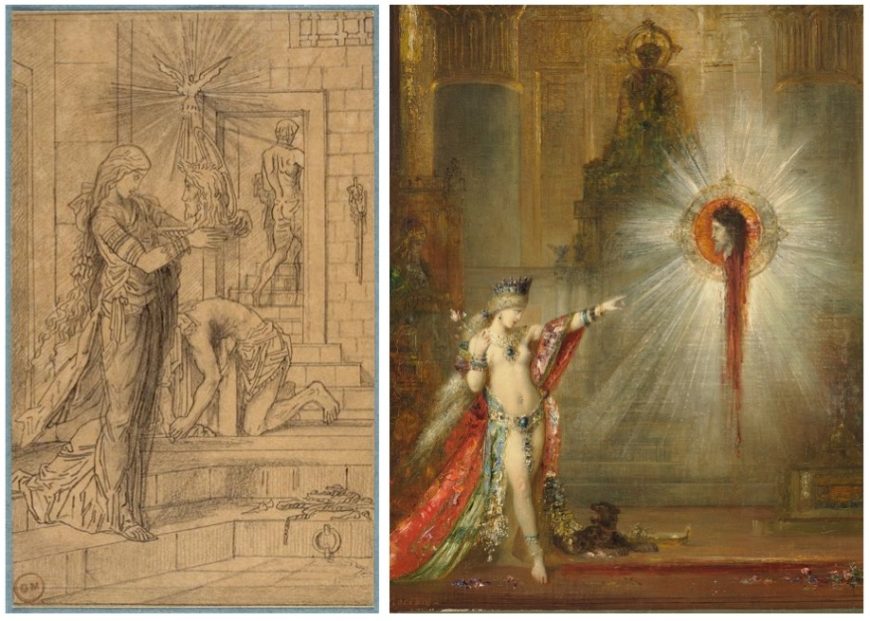

Another version of the subject further illustrating Moreau’s love for detail and complexity is the so-called Tattooed Salome.

The viewer here is left wondering whether we are to understand the markings as imprinted on Salome or if they instead form part of a decorative pattern on the canvas that are more apparent against the light tones of her body.

On each side of the lotus “tattoo,” there are two giant eyes staring at the viewer. These “tattooed” eyes, complete with a pair of eyebrow decorations, reveal a mirroring face, whilst Salome’s “real” eyes are lowered. The “tattooed” gaze catch the viewer’s and block him or her, as it were, from exploring the woman’s body, acting as an additional layer of protection against our voyeurism. Further down, we see a “tattooed” Gorgon-like creature, with her tongue sticking out, and reptilian figures undulating around Salome’s inner thighs.

Matter and spirit appear woven together in another image by Moreau, known as Salome Entering the Banquet Hall, in which the temptress raises the platter with Saint John’s head towards the dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit. In this drawing, Salome holds the platter with the saint’s head close to the level of her own, while she peers intently into his eyes. Above them both, but clearly closer to Saint John, the Holy Spirit reigns supreme, while the executioner exists the scene, blade on his shoulder. Another painting by Moreau, Apparition, marks another confrontation of sorts between Salome and the head of Saint John.

Moreau’s long standing interest in the story of Salome and its many interpretations is made apparent through the artist’s varied approaches to the theme and in his desire to transcend to the symbolism Salome traditionally enacts—as a warning against temptation. Instead, Moreau looks to Salome as link between matter and spirit. So intertwined are Moreau’s artistic agenda and Salome’s symbolic content that one could credibly assert that even as Moreau created images of Salome, Salome shaped him.

Footnotes

[1] Salome was taken up as a theme numerous times in literature as in the visual arts. If we are to consider the 19th century only, Heine’s Atta Troll, Flaubert’s Three Stories (the third, Hérodias, possibly influenced by Moreau’s painting), Massenet’s Hérodiade and Wilde’s Salome come to mind. Furthermore, it is quite possible that Moreau was acquainted with Flaubert’s 1862 Salammbô and with Mallarmé’s 1864 Hérodiade, which would have influenced his approach. See Julius Kaplan’s “Salome” subchapter in Gustave Moreau. Theory, Style and Content (Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI, 1982).

[2] “Thus, in my Salomé, I wanted to depict a figure of a sibyl and religious enchantress having a mysterious character. So then I designed the costume that is like a reliquary.” See Écrits sur l’art par Gustave Moreau. Textes établis, présentés et annotés par Peter Cooke. A Fontfroide, Bibliothèque artistique et littéraire, MMII, p. 99. See also Peter Cooke, Gustave Moreau: History Painting, Spirituality and Symbolism (Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2014), pp. 81-93.

[3 ]“This woman who represents the eternal woman, flimsy bird, often fatal, walking through life with a flower in hand, in search of her vague ideal, often terrible, and always walking, trampling everything under her feet, even geniuses and saints. This dance is executed, this mysterious walk takes place before the death who looks at her incessantly, gaping and attentive, and before the executioner whose sword strikes… A saint, a decapitated head are at the end of her path which will be strewn with flowers. Everything happens in a sanctuary that elevates the spirit towards the gravity and the idea of higher things.” See Écrits, pp. 97-8.

[4] When speaking of another of his artworks, Jupiter and Europa, Moreau makes his goal clear: “I want, when I address materialist and anti-spiritual youth without respect for art or religion, I want, I’d say, to bring them through the spectacle of the eyes to comprehend the beautiful, which will make them understand the good.” See Écrits, p.79 and Scott C. Allan, “Gustave Moreau and the Afterlife of French History Painting”, PhD thesis, Princeton, pp. 48-54.

[5] Écrits, p. 344. His eclecticism became proverbial as he used a vast variety of sources — Egyptian, Indian, Roman, Etruscan, Persian, Chinese, Moorish, Turkish, etc. — for the costumes and the architectural settings in his paintings.

[6] See Peter Cooke, “It isn’t a Dance: Gustave Moreau’s ‘Salome’ and ‘The Apparition’” in Dance Research, vol. 29, no. 2 (winter 2011).

Additional resources

Arnold Böcklin, Self-Portrait with Death Playing the Fiddle

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Arnold Böcklin, Self-Portrait with Death Playing the Fiddle, 1872, oil on canvas, 75 x 61 cm (Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Família

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\)

120 years and counting

Although Antoni Gaudí was influenced by John Ruskin’s analysis of the Gothic early in his career, he sought an authentic Catalan style at a time, the late 19th century, when this region (currently mostly in northern Spain) was experiencing a resurgence of cultural and political pride. Ruskin, an English critic, rejected ancient classical forms in favor of the Gothic’s expressive, even grotesesque qualities. This interest in the value of medieval architecture resulted in Gaudi being put in charge of the design of Sagrada Família (Sacred Family) shortly after construction had begun.

Gaudí was a deeply religious Catholic whose ecstatic and brilliantly complex fantasies of organic geometry are given concrete form throughout the church. Historians have identified numerous influences especially within the northeast façade, the only part of the church he directly supervised. The remainder of the church, including three of the southwest transept’s four spires, are based on his design but were completed after Gaudí’s death in 1926. These include African mud architecture, Gothic, Expressionist, of course a variant of Art Nouveau that emphasizes marine forms.

The iconographic and structural programs of the church are complex but its plan is based on the traditional basilica cruciform found in nearly all medieval cathedrals. However, unlike many these churches, Sagrada Familia is not built on an east-west axis. Instead, the church follows the diagonal orientation that defines so much of Barcelona, placing the church on a southeast-northwest axis.

The Glory Façade (southeast):

This will eventually be church’s main façade and entrance. As with the transcept entrances, it holds a triple portal dedicated to charity, faith, and hope. The façade itself is dedicated to mankind in relation to the divine order.

The Passion Façade (southwest):

Dedicated to the Passion of Christ, its four existing belltowers are between 98 and 112 meters tall and are dedicated to the apostles James the Lesser, Bartholomew, Thomas and Philip (left to right). Josep Maria Subirachs is responsible for the façade sculpture.

The Nativity Façade (northeast):

Depicts the birth of Christ and is the only façade to be completed during Gaudi’s lifetime. its four existing belltowers are between 98 and 112 meters tall and are dedicated to the saints Barnabas, Jude, Simon and Matthew (left to right).

Ten additional belltowers (98-112 meters high) are planned though these will be overwhelmed by six towers that will be significantly taller. Four of these towers will be dedicated to the Evangelists, one to the Virgin Mary, and the grandest, rising to 170 meters, to Jesus Christ.

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): What Sagrada Familia will look like when construction is complete

Additional resources:

Official site of Sagrada Família

God’s Architect: Antoni Gaudi’s glorious vision, CBS documentary

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

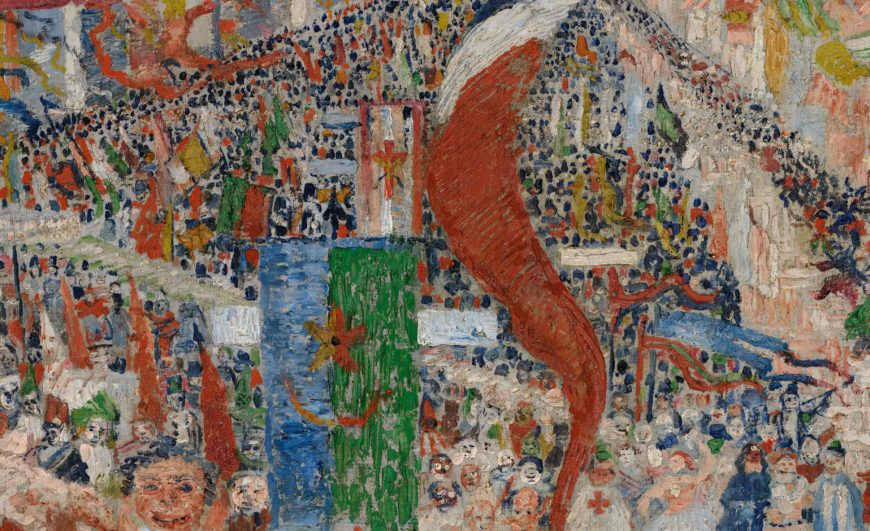

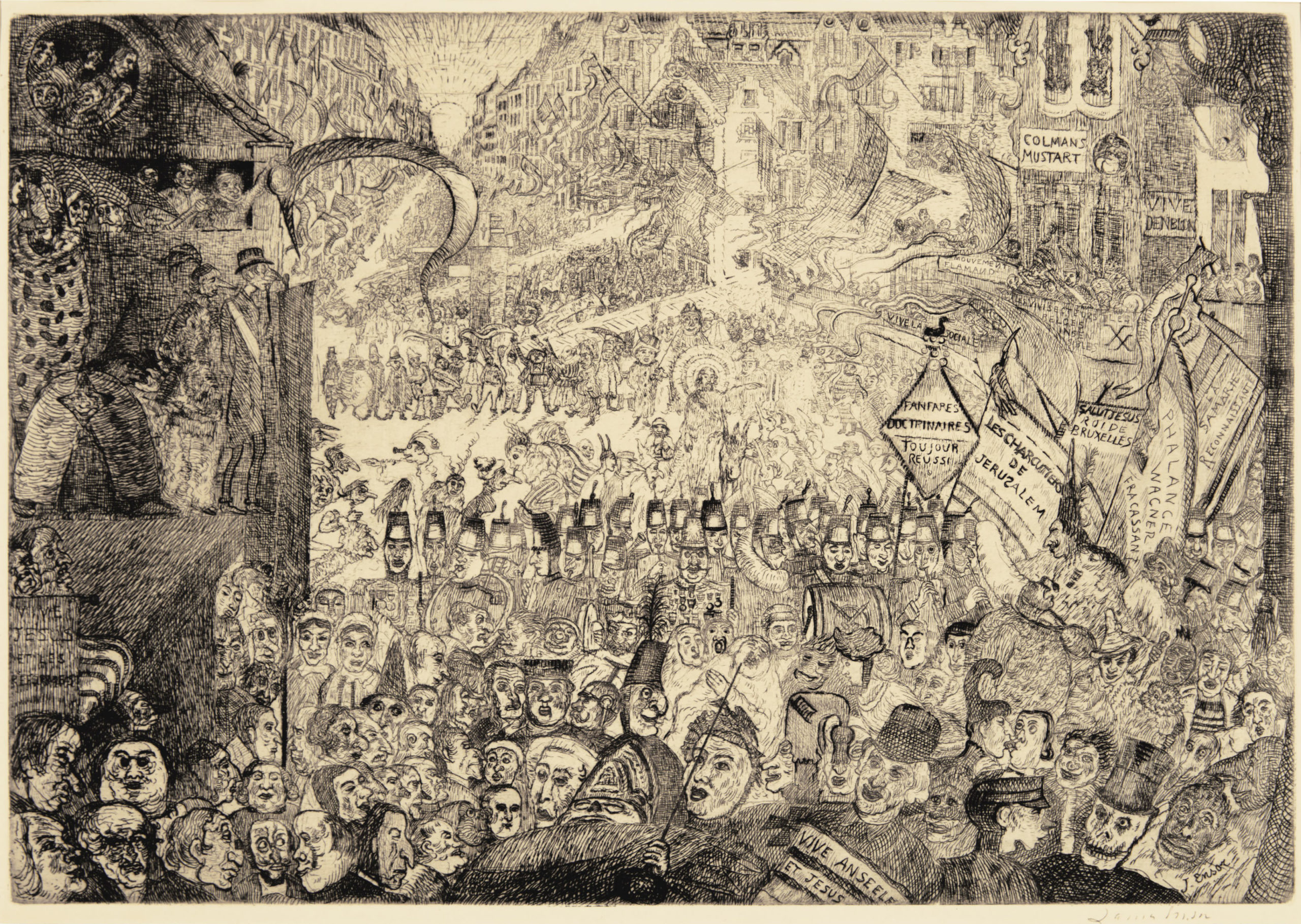

James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 is one of the largest and most ambitious modern paintings of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Over eight feet high and fourteen feet wide, it depicts a huge parade flooding down a wide street toward the viewer. The deep central space framed by reviewing stands and balconies suggests the stage of a proscenium theater. The lurid colors used to paint people, signs, and banners clash, and dozens of grotesque theatrical faces in the crowd, many wearing masks, compete for our attention. In the foreground the raucous mob threatens to spill out of the canvas and sweep us up into the chaos.

The painting’s style and technique are as aggressive as its subject. The paint is applied in crude heavy strokes and slabs to create a rough, heavily-textured surface. Bright red dominates, and it is accompanied by its complement, green, as well as the other primaries blue and yellow. There is no shading, and the overall effect is flat and poster-like. The colors are brighter and lighter in the background, which sparkles with patterns of dots representing the distant crowds and rays of light that criss-cross the waving banners.

Humanity mocked

The painting’s title refers to the traditional subject of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, here transposed to contemporary Belgium. The painting is also reminiscent of the carnival parades of Mardi Gras, the Christian festival that precedes Lent. The small gold-haloed figure of Christ rides a donkey in the center of the painting’s upper portion behind the marching band. He is surrounded by a small group of masked figures whose long noses point up at him, and he raises his arm in a gesture of blessing. Most of the crowd, however, pays no attention to Christ.

Christ’s Entry into Brussels is far from being a conventional religious image of Christ as the savior of humanity. The painting mocks humanity, as well as human beliefs and institutions, both civic and religious. The grotesque parade is led by a bishop dressed in red with a gold miter who is marching out of the painting in the middle of the foreground.

The sea of masks and faces behind him includes priests, government officials, soldiers, a military band preceded by a heavily-decorated leader, and caricatures of many types of ordinary citizens. A masked man dressed in the blue coat and white sash of the city’s mayor watches the parade from a reviewing stand on the right, accompanied by a group of elaborately-costumed masked figures. Ensor himself appears in profile as the yellow-clad figure in the tall conical red hat on the left.

Political critique or personal expression?

A red banner inscribed with the slogan “Vive la sociale” or “Long live the social [revolution]” stretches across the top of the painting and refers to contemporary politics and social reformers. Ensor’s sources for the painting included newspaper photos of an enormous socialist demonstration held in Brussels in 1886. The image of Christ had direct political significance as well; socialist politicians and writers in nineteenth-century France and Belgium frequently portrayed Christ as an exemplary social reformer who worked to improve the condition of the impoverished masses. Ensor is known to have been supportive of liberal social reforms and highly critical of powerful conservative institutions in Belgium, but Christ’s Entry into Brussels does not clearly support any particular political position. On the contrary, it seems to be a wholesale condemnation of both humanity and human ideologies.

Ensor created many works depicting scenes from the life of Christ, some of which were images of suffering in which he portrayed himself as Christ. These self-portraits display Ensor’s sense of persecution as an artist. Although he was a recognized leader among the Belgian avant-garde in the 1880s, he felt unfairly treated by critics and fellow artists. Some of his works were refused by Les XX, the Belgian avant-garde exhibition society he helped to found, and his anger and resentment are evident in many works.

In Christ’s Entry into Brussels, a figure vomits on Les XX’s emblem painted in red on the green balcony above Ensor’s self-portrait.. Thus, among the many topics it addresses, the huge painting expresses Ensor’s personal bitterness toward the art world. It is also often interpreted as symbolically portraying the avant-garde artist as a Christ-like prophet misunderstood by the public.

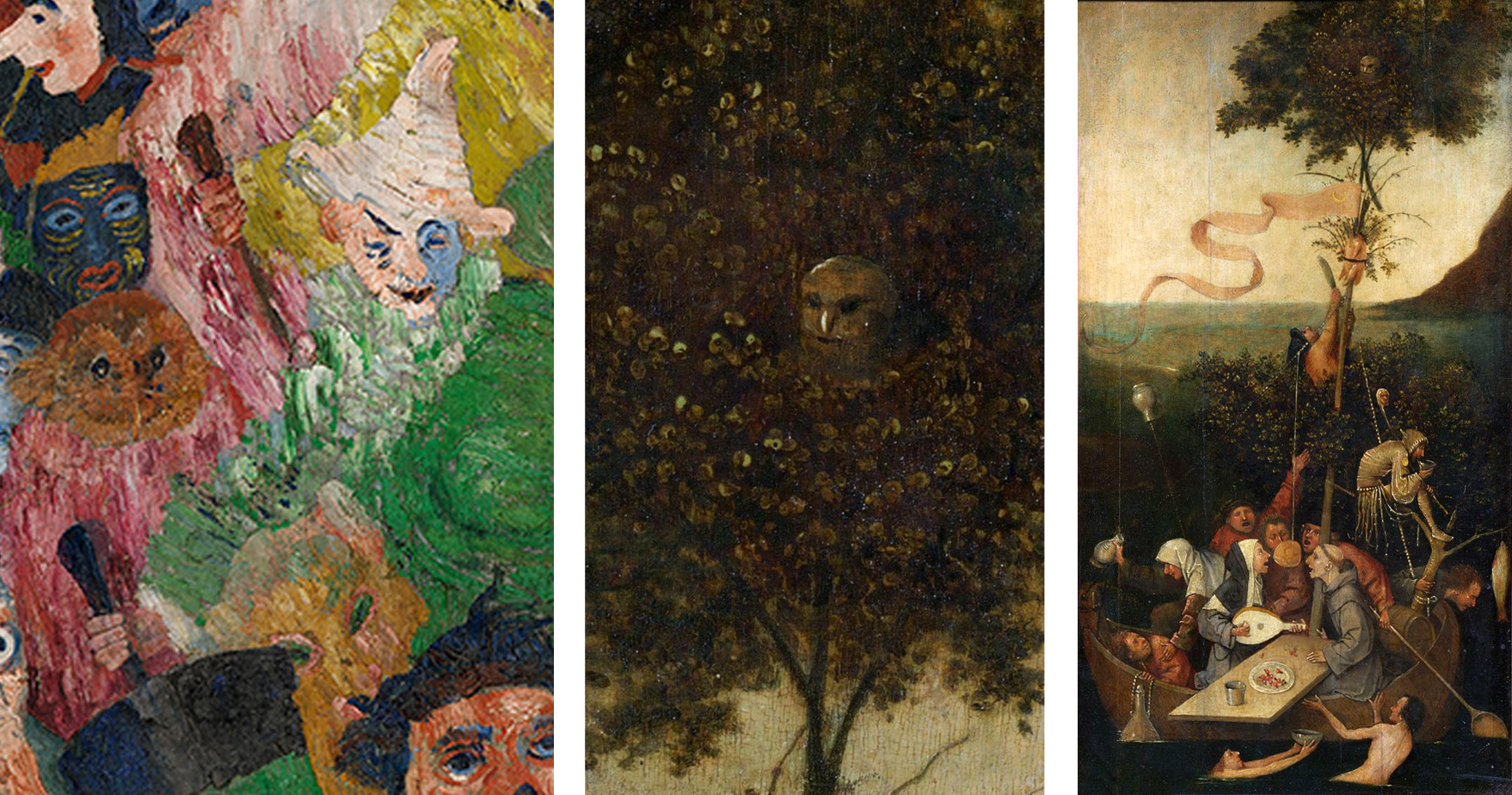

The northern tradition

Ensor painted Christ’s Entry into Brussels when he was twenty-eight. His earliest paintings were Realist and Impressionist in style and subject matter, but in the mid-1880s his work became increasingly idiosyncratic. He adopted subjects associated with prominent artists of the Northern Renaissance and Baroque tradition, including Bosch, Bruegel, Rembrandt, and Rubens. Christ’s Entry into Brussels echoes Bruegel’s Procession to Calvary, a painting in which Christ is also lost in a largely oblivious crowd.

Ensor frequently borrowed fantastic figures and grotesque motifs from Northern Renaissance art, and like Bosch and Bruegel he reveled in the exposure of human folly. In his self-portrait in Christ’s Entry into Brussels Ensor extends his arm down towards the face of an owl, one of many faces in the crowd. While we now associate owls with wisdom, the owl is also a traditional symbol of foolishness. It appears often in this guise in Bosch’s paintings, including his Ship of Fools, where it peers out of the top of the tree.

Masks

The masks that are so prominent in Christ’s Entry into Brussels became a central subject for Ensor in the 1880s. His family owned a curiosity shop that sold papier-mâché Carnival masks in the seaside town of Ostend, making masks both personal and highly symbolic objects in Ensor’s work. Self Portrait with Masks shows him surrounded by a terrifying array of blindly staring masks, but his own portrait is also a sort of mask; it is directly modeled after self-portraits of the great Flemish Baroque painter Peter-Paul Rubens.

In Christ’s Entry into Brussels even apparently unmasked figures have mask-like, caricatured faces suggesting that everyone wears some sort of mask. Ensor’s masked figures represent humanity as superficial, hypocritical, and grotesque. Masks also confer anonymity and allow people to act outside social laws without fear of being recognized and punished.

In Christ’s Entry into Brussels the theme of personal irresponsibility and freedom is enhanced by the association to a Carnival parade. During Carnival, society’s rules are dropped, and the usual social order is turned upside down; rich and poor switch roles, the beggar becomes king or queen for the day. Carnival is often described as serving as a sort of relief valve for the ordinary pressures of society, as well as a moment when underlying truths are exposed. In Christ’s Entry into Brussels the masks can be understood as revealing rather than hiding the true nature of humanity and human society.

Skeletons

Skeletons were another central subject in Ensor’s art, and a skeleton figure wearing a top hat appears prominently in the lower left of Christ’s Entry into Brussels. It adds a macabre reminder of death’s presence in the midst of life, a traditional artistic theme known as memento mori that was very popular in Northern Baroque painting. In numerous works Ensor portrayed skeletons and masked figures in enigmatic scenes that mock the foolishness and cruelty of human behavior. Ensor’s skeletons frequently represent art critics persecuting him.

In Skeletons Fighting over a Hanged Man two skeletons wearing elaborate costumes duel over mannequins using a mop and broom for weapons. Masked figures carrying knives push through the doorways and seem to menace the duelists on both sides. In the left foreground, a third skeleton watches the combat with paintbrush in hand and a palette on his lap, reminding us that for Ensor his paintbrush was both his weapon and his claim to immortality.

Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 is an ambitious and idiosyncratic painting that enlists multiple historical and contemporary artistic sources to address topics that range from the personal to broad social concerns. It was not publicly exhibited until 1929, but prints of it were widely circulated, and Ensor’s highly individualized art influenced many later modern artists, most notably those associated with Expressionism.

Fernand Khnopff

Fernand Khnopff, Jeanne Kéfer

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Fernand Khnopff, Jeanne Kéfer, 1885, oil on canvas (The Getty Center, Los Angeles)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

No photos

Figure \(\PageIndex{66}\): More Smarthistory images…

Fernand Khnopff, I Lock my Door Upon Myself

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Fernand Khnopff, I Lock My Door Upon Myself, 1891 (Neue Pinakothek, Munich)

The essential aim of our art is to objectify the subjective (the externalization of the Idea) instead of subjectifying the objective (nature seen through the eyes of a temperament.¹

Painting and poetry

The aim of the Symbolists was to turn away from what they saw as the materialism of Impressionism. Instead, they sought to be evocative, to suggest a mood, or an abstract idea—to make their work analogous to poetry and music (neither of which depict the external world in a literal way). So perhaps it should come as no surprise that Khnopff’s painting, I Lock my Door Upon Myself (1891), takes its title and inspiration from a poem, “Who Shall Deliver Me?” by Christina Rossetti (the sister of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a Pre-Raphaelite painter who was an important influence on Khnopff).

A bastion against the vulgar world?

The poem’s title clearly recalls a biblical passage, “O wretched man that I am! who shall deliver me from the body of this death?” (Romans 7:24)—and the subject is an internal conflict from which only God can deliver us. In Khnopff’s hands though, Rossetti’s poem becomes a more general and secular meditation on inner conflict or mood. Yet the female figure, with her otherworldly stare, shows no sign of struggle.

Given the title and the stanza of the poem the title is taken from, are we to read the objects that surround the figure as “symbols” (in a personal, not literal, sense) of an inner struggle? Or perhaps we are not meant to look to the poem at all for the painting’s meaning—since Khnopff only took one line from it, “I Lock my Door Upon Myself.” If the latter is the case, then perhaps (as Michelle Facos suggests in her book, An Introduction to Nineteenth Century Art) the painting is about turning away from the world, similar to what Khnopff did in his personal life when he built a “fortress-like home” for himself in Brussels “as a bastion against the vulgar, outside world.”

In the foreground of the painting are the three distinct sets of withering, orange irises which punctuate the three-part composition. Aside from the curvilinear form of the woman locked behind a table of some sort (or is it an altar, or a tomb?), the painting is dominated by circles, squares and rectangles, and everything—including the woman herself—is painted in muted tones. It is as though Khnopff is suggesting that the “reality” we see isn’t very real at all.

What we see

In the first segment, reading from left to right, we see part of a circle, a truncated rectangle with a decorative floral pattern, another circle that may be a mirror, and the shallow recess of a doorway that doesn’t seem to open onto anything, with a window it that similarly looks out onto nothing.

The next segment is divided into three horizontal bands framed by wide vertical planks. At the top is a shelf that holds a bust of Hypnos, the Greek god of sleep (brother of Thanatos, the god of death), and a red poppy. The bust is among the most sharply defined forms in the painting and its blue wing subtly echoes the red hair of the woman who sits below. In the right most segment, we see a lone figure in a desolate townscape reminiscent of Caspar David Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea (1809).

There are other objects in the painting that are even more mysterious, a small, crown-like charm dangles from above on a silver chain, a face perhaps, within two circles, on the lower right. And what is the long object on the table in front of the woman? And is that a spear beside her?

Of course we want to be able to read the painting, but so much of it is ambiguous and undecipherable. What we are left with is a mysterious and haunting image that speaks to the anti-materialist and inward-looking interests of so much art of the late nineteenth century.

The shift from modern life

This shift from modern life, to the inner psyche had many causes. It was, at least in part, a reaction against the rapid industrialization and urbanization that occurred in much of Europe in the nineteenth century. And similarly, it was a reaction against the art that had celebrated this new urban reality (see, for example, Impressionist paintings of the city such as Auguste Renoir’s Pont Neuf, Paris).

One response to the rapid intrusion of modernity—a response favored by many late-nineteenth century artists—was to turn inward, “whereas Naturalists, Realists and Impressionists concentrated on the appearance of modernity, Symbolists explored its emotional, psychological, and spiritual aspects and searched for a pictorial language that could convey the experience of modernity.”²

WHO SHALL DELIVER ME? (by Christina Rossetti)

God strengthen me to bear myself;

That heaviest weight of all to bear,

Inalienable weight of care.

All others are outside myself;

I lock my door and bar them out

The turmoil, tedium, gad-about.

I lock my door upon myself,

And bar them out; but who shall wall

Self from myself, most loathed of all?

If I could once lay down myself,

And start self-purged upon the race

That all must run ! Death runs apace.

If I could set aside myself,

And start with lightened heart upon

The road by all men overgone!

God harden me against myself,

This coward with pathetic voice

Who craves for ease and rest and joys

Myself, arch-traitor to myself ;

My hollowest friend, my deadliest foe,

My clog whatever road I go.

Yet One there is can curb myself,

Can roll the strangling load from me

Break off the yoke and set me free

1. Gustave Kahn, “Response of the Symbolists” (1886) as quoted in Harrison and Wood, Art in Theory, 1815-1900, p. 1017

2. As quoted in Michelle Facos, Symbolist Art in Context, p. 61

Additional resources:

J. Paul Getty Museum biography of the artist

Fernand Khnopff: Inner Visions and Landscapes exhibition at the Mcmullen Museum of Art, September 9 – December 5, 2004

Jeffrey Howe, “Fernand Khnopff (1858-1921): Belgian Symbolist”, essay for Fernand Khnopff: Inner Visions and Landscapes exhibition at the Mcmullen Museum of Art, September 9 – Decembe 5, 2004

The Symbolist Movement: To Make the Invisible Visible (Radford University)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Franz von Stuck, The Sin

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Franz von Stuck, The Sin, 1893, 94.5 x 59.5cm (Neue Pinakothek, Munich)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Hector Guimard, Cité entrance, Métropolitain, Paris

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Hector Guimard, Cité entrance, Métropolitain, c.1900, painted cast iron, glazed lava, and glass, roughly 14 x 18′, Île de la Cité, Paris

Gustav Klimt

Gustav Klimt, Beethoven Frieze

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Gustav Klimt, Beethoven Frieze, 1902, Vienna Secession Hall

The heirs of the Austrian Jewish collector who owned this work before World War II lost their case to recover it in 2015. Learn more in the March 7, 2015 New York Times article.

Gustav Klimt, The Kiss

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Gustav Klimt, The Kiss, 1907-8, oil and gold leaf on canvas, 180 x 180 cm (Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna)

Gustav Klimt, Death and Life

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Gustav Klimt, Death and Life, 1910, reworked 1915, oil on canvas, 178 x 198 cm (Leopold Museum, Vienna)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch, The Storm

by DR. JULIANA KREINIK and DR. AMY HAMLIN

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): Edvard Munch, The Storm, 1893, oil on canvas, 36 1/8 x 51 1/2″ / 91.8 x 130.8 cm (Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

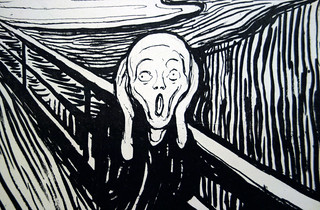

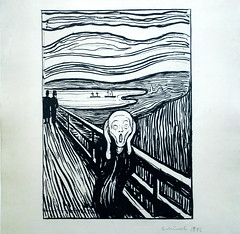

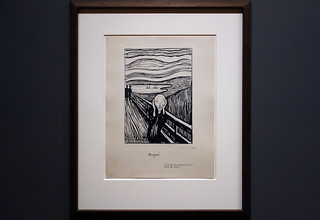

Edvard Munch, The Scream

Second only to Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Edvard Munch’s The Scream may be the most iconic human figure in the history of Western art. Its androgynous, skull-shaped head, elongated hands, wide eyes, flaring nostrils and ovoid mouth have been engrained in our collective cultural consciousness; the swirling blue landscape and especially the fiery orange and yellow sky have engendered numerous theories regarding the scene that is depicted. Like the Mona Lisa, The Scream has been the target of dramatic thefts and recoveries, and in 2012 a version created with pastel on cardboard sold to a private collector for nearly $120,000,000 making it the second highest price achieved at that time by a painting at auction.

Conceived as part of Munch’s semi-autobiographical cycle “The Frieze of Life,” The Scream’s composition exists in four forms: the first painting, done in oil, tempera, and pastel on cardboard (1893, National Gallery of Art, Oslo), two pastel examples (1893, Munch Museum, Oslo and 1895, private collection), and a final tempera painting (1910, National Gallery of Art, Oslo). Munch also created a lithographic version in 1895. The various renditions show the artist’s creativity and his interest in experimenting with the possibilities to be obtained across an array of media, while the work’s subject matter fits with Munch’s interest at the time in themes of relationships, life, death, and dread.

For all its notoriety, The Scream is in fact a surprisingly simple work, in which the artist utilized a minimum of forms to achieve maximum expressiveness. It consists of three main areas: the bridge, which extends at a steep angle from the middle distance at the left to fill the foreground; a landscape of shoreline, lake or fjord, and hills; and the sky, which is activated with curving lines in tones of orange, yellow, red, and blue-green. Foreground and background blend into one another, and the lyrical lines of the hills ripple through the sky as well. The human figures are starkly separated from this landscape by the bridge. Its strict linearity provides a contrast with the shapes of the landscape and the sky. The two faceless upright figures in the background belong to the geometric precision of the bridge, while the lines of the foreground figure’s body, hands, and head take up the same curving shapes that dominate the background landscape.

The screaming figure is thus linked through these formal means to the natural realm, which was apparently Munch’s intention. A passage in Munch’s diary dated January 22, 1892, and written in Nice, contains the probable inspiration for this scene as the artist remembered it: “I was walking along the road with two friends—the sun went down—I felt a gust of melancholy—suddenly the sky turned a bloody red. I stopped, leaned against the railing, tired to death—as the flaming skies hung like blood and sword over the blue-black fjord and the city—My friends went on—I stood there trembling with anxiety—and I felt a vast infinite scream [tear] through nature.” The figure on the bridge—who may even be symbolic of Munch himself—feels the cry of nature, a sound that is sensed internally rather than heard with the ears. Yet, how can this sensation be conveyed in visual terms?

Munch’s approach to the experience of synesthesia, or the union of senses (for example the belief that one might taste a color or smell a musical note), results in the visual depiction of sound and emotion. As such, The Scream represents a key work for the Symbolist movement as well as an important inspiration for the Expressionist movement of the early twentieth century. Symbolist artists of diverse international backgrounds confronted questions regarding the nature of subjectivity and its visual depiction. As Munch himself put it succinctly in a notebook entry on subjective vision written in 1889, “It is not the chair which is to be painted but what the human being has felt in relation to it.”

Since The Scream’s first appearance, many critics and scholars have attempted to determine the exact scene depicted, as well as inspirations for the screaming figure. For example, it has been asserted that the unnaturally harsh colors of the sky may have been due to volcanic dust from the eruption of Krakatoa in Indonesia, which produced spectacular sunsets around the world for months afterwards. This event occurred in 1883, ten years before Munch painted the first version of The Scream. However, as Munch’s journal entry—written in the south of France but recalling an evening by Norway’s fjords also demonstrates—The Scream is a work of remembered sensation rather than perceived reality. Art historians have also noted the figure’s resemblance to a Peruvian mummy that had been exhibited at the World’s Fair in Paris in 1889 (an artifact that also inspired the Symbolist painter Paul Gauguin) or to another mummy displayed in Florence. While such events and objects are visually plausible, the work’s effect on the viewer does not depend on one’s familiarity with a precise list of historical, naturalistic, or formal sources. Rather, Munch sought to express internal emotions through external forms and thereby provide a visual image for a universal human experience.

Additional resources:

This painting on the Google Art Project

Art through Time: The Scream

Short biography of the artist from the J. Paul Getty Museum

Walter Gibbs, “Stolen Munch Paintings are Recovered,” NYTimes, September 1, 2006

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Léon Bakst, “Costume design for the ballet The Firebird”

by THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

Video \(\PageIndex{12}\): Video from The Museum of Modern Art.

Louis Comfort Tiffany

Louis Comfort Tiffany, Vase

by THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

Video \(\PageIndex{13}\): Video from The Museum of Modern Art.

Additional resources:

Louis Comfort Tiffany, Hair Ornament

by THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Video \(\PageIndex{14}\): Louis Comfort Tiffany, Hair Ornament, c. 1904, gold, silver, platinum, black opals, boulder opals, demantoid garnets, rubies, enamel, H. 3 1/4″ / 8.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.