2.9: Symbolism / Art Nouveau

- Page ID

- 107360

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Symbolism and Art Nouveau

Many artists in the late 19th century broke from naturalistic representation and sought visual equivalents to poetry and music.

c. 1880 - 1910

Art Nouveau

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

Victor Horta’s Tassel House in Brussels is one of the earliest examples of the Art Nouveau style. Horta designed the building’s architecture and every detail of the interior decoration and furnishings, making the house into a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total art work in multiple media. The repeated use of organically curved, undulating lines — often called whiplash lines — unifies the design, repeating in the floor tiles, wall painting, ironwork, and even in the structure of the spiraling staircase and surging entryways.

A modern style using modern materials

Art Nouveau artists and designers created a completely new style of decoration, rejecting the widespread nineteenth-century practice of copying historical, and especially Classical and Medieval, forms. While each designer invented their own decorative motifs, organic, often plant-based, forms and the whiplash line became hallmarks of Art Nouveau design, appearing in multiple media and contexts.

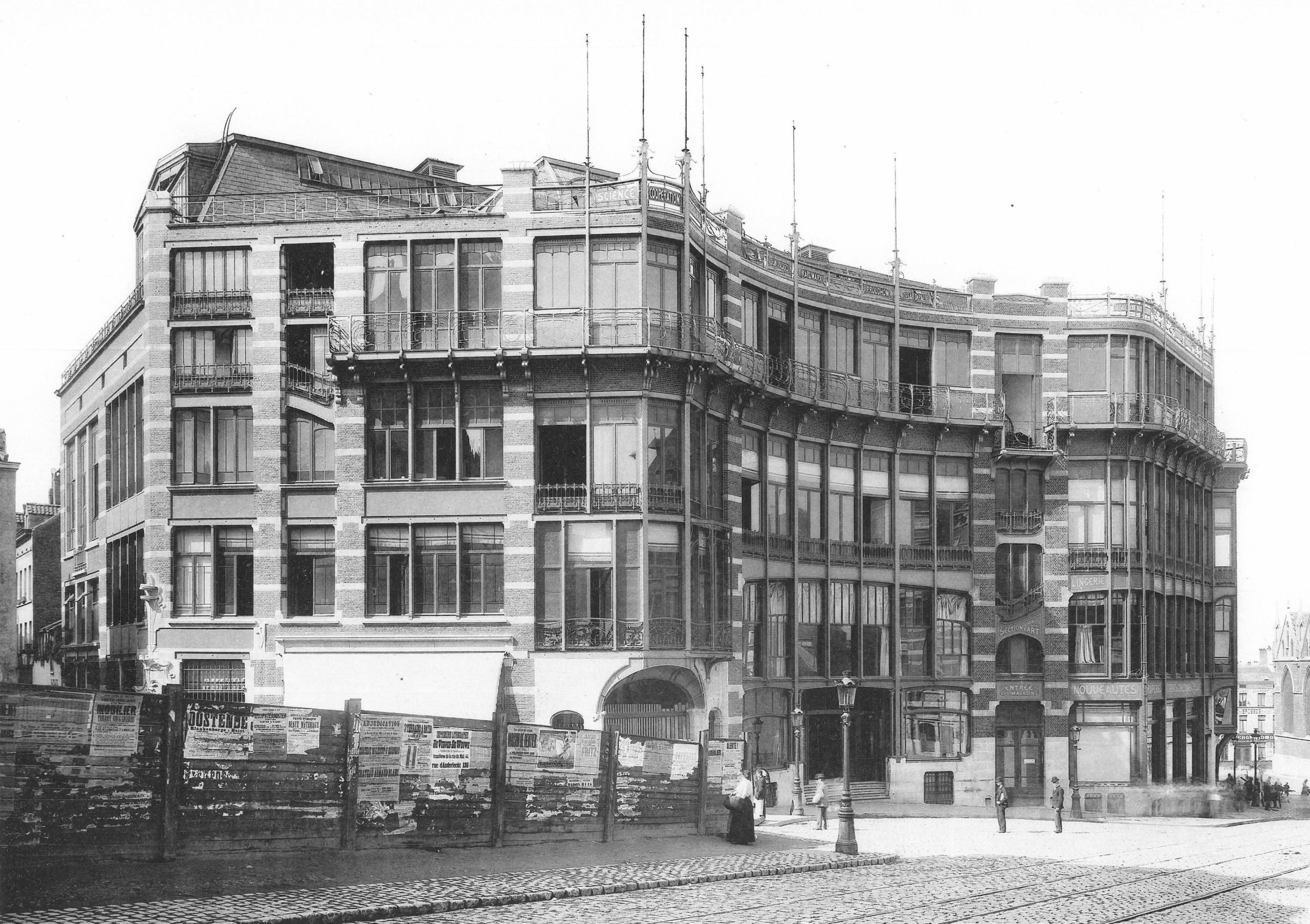

Art Nouveau architects and designers also embraced modern building materials, notably cast iron. Cast iron is both stronger and more flexible than traditional wood or stone and allows for much thinner supports, like the slender columns in Horta’s own house. Iron support structures also made it possible to create curved facades with large windows, which became prominent elements in many Art Nouveau buildings, including Horta’s Maison du Peuple.

An international style

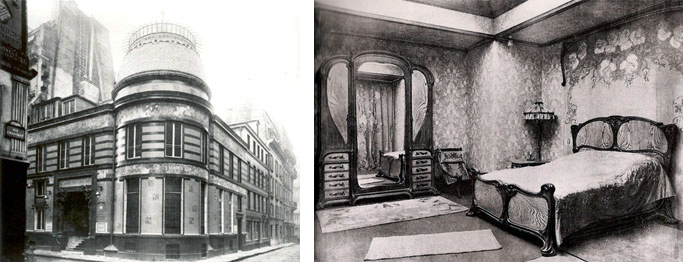

Art Nouveau is only one of many names given to this international fin-de-siècle style, which had many regional variations. The term (French for “New Art”) derives from La Maison de L’Art Nouveau, the Paris art gallery run by Siegfried Bing, who was a major promoter of the new style, as well as of Japonisme and the Nabis. In addition to marketing individual objects, Bing commissioned artists and designers to create model rooms in his gallery to display Art Nouveau ensembles that included furniture, wallpaper, carpets, and paintings.

In addition to Paris, major centers of the modern fin-de-siècle style included Brussels, Glasgow, Munich (where it was known as Jugendstil or Youth Style), and Vienna (where it was called Secession Style). Barcelona’s Catalan Modernism, especially Antoní Gaudí‘s architecture and decorative designs, is also closely related to Art Nouveau.

Luxury design for the masses

French Art Nouveau was linked to government-supported efforts to expand the decorative arts and associated craft industries. Private residences and luxury objects were the focus for many Art Nouveau designers, including Emile Gallé, who made both decorative glass and furniture. Despite the close association of Art Nouveau with luxury items, the style is also apparent in urban design, public buildings, and art for the masses. Horta’s Maison du Peuple was the center for the socialist Belgian Workers’ Party, and among the most famous examples of Art Nouveau style are Hector Guimard’s entrances to the Paris Metro, the city’s new public transportation system.

Like Horta’s designs for the Tassel House, Guimard used cast iron and invented stylized motifs based on plant forms. Industrially fabricated in modular units, the cast iron was relatively cheap, but it was painted green to resemble oxidized copper, a much more expensive material that adds a sense of luxury to the elaborate entrances. The use of modules made it possible to individualize each station while maintaining stylistic unity throughout the city.

Art Nouveau designs were also widely visible in the advertising posters that decorated Paris. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Alphonse Mucha, and Jules Chéret depicted famous fin-de-siècle performers such as Jane Avril, Sarah Bernhardt, and Loïe Fuller. Their posters stylized the female body and used sinuous whiplash lines, decorative plant forms, and flattened abstract shapes to create vivid decorative images.

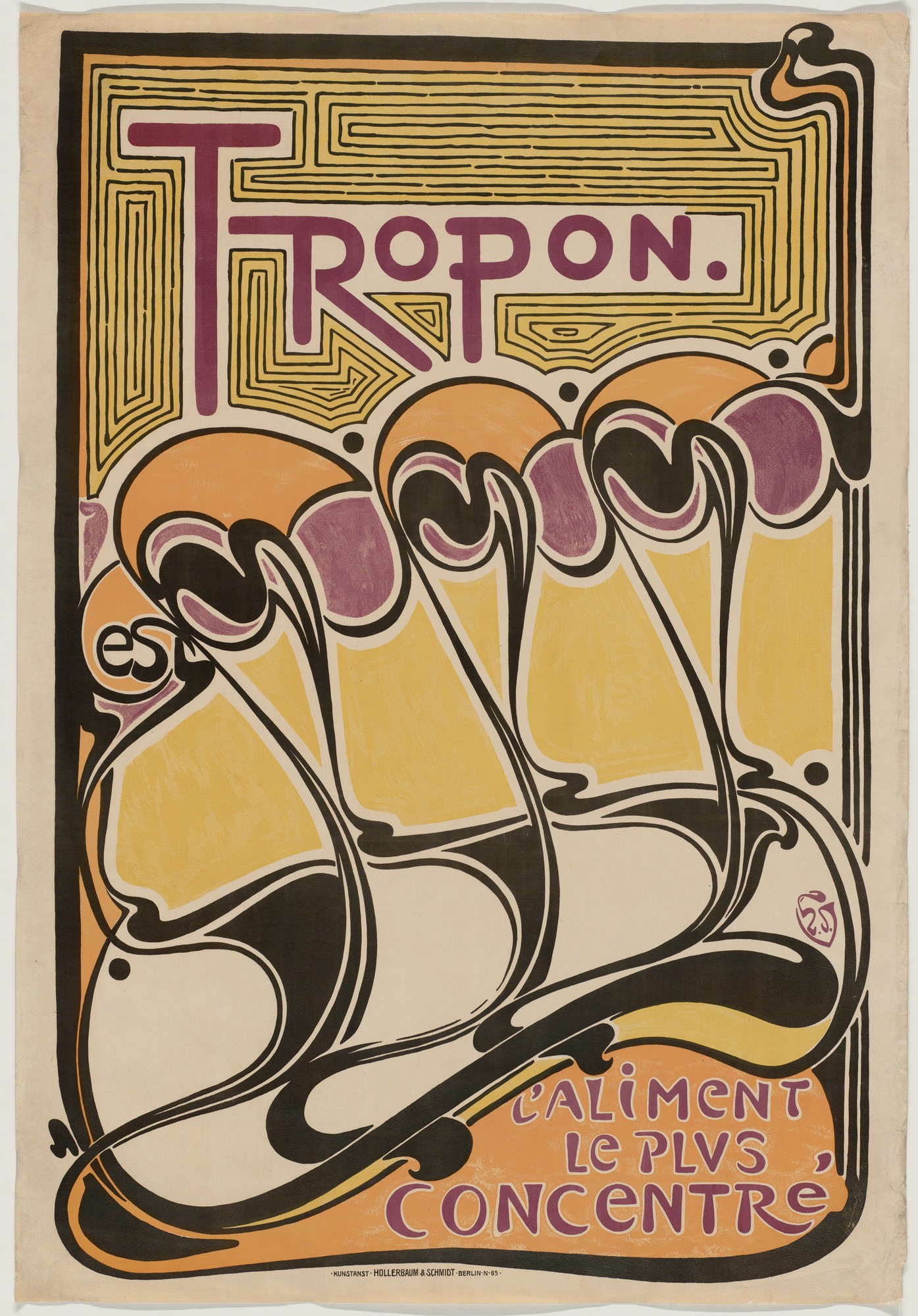

In a poster for the nutritional supplement Tropon, Henry van de Velde explored the decorative and suggestive potential of non-representational forms, using the whiplash line to create an abstract design of organic shapes that suggest both plant-like growth and dancing figures in the rising diagonal of repeated forms.

A holistic approach

Van de Velde worked in many different media, designing buildings, interiors, furniture, and decorative objects as well as posters. In the Continental Havana Company building in Berlin he used sinuous curves to integrate the shelving, doorways, alcoves, furniture, and walls into a unified organic whole.

The English designer William Morris and the English Arts and Crafts Movement that he initiated were a key influence on van de Velde and many other designers associated with Art Nouveau. Morris promoted a holistic approach to interior decoration as well as advocating for the social importance of design and high quality craftwork. In 1907 van de Velde founded the School of Arts and Crafts in Weimar, Germany, which promoted similar values. It later became the famous modern art and design school, the Bauhaus, which maintained the tradition of integrating art, craft, and design for the improvement of society.

Glasgow style

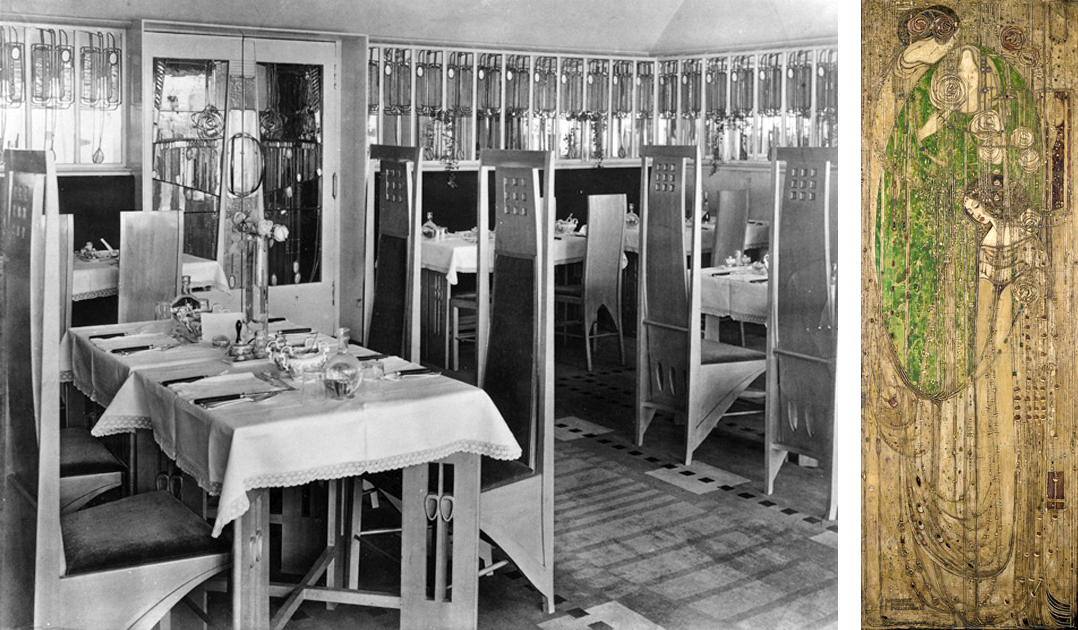

Curving whiplash lines are a common characteristic of French and Belgian Art Nouveau, but architects and artists working in Glasgow developed a more rectilinear style exemplified by the Willow Tea Room. Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald designed every component of the tea room, including the architecture, stained glass, decorative panels, furniture, cutlery, and staff uniforms. In keeping with Art Nouveau artists elsewhere they developed original stylized design motifs based on plant forms, but theirs were rigidly contained within elongated rectangles rather than expanding into supple curves.

Vienna Secession style

The Viennese Secession style also combined strict geometric forms with stylized organic decoration. Like Guimard’s entrances to the Paris Metro, Otto Wagner’s stations for Vienna’s public transportation system displayed the city’s modernity and wealth in their iron construction and their luxurious gold sunflower-motif decoration.

Joseph Maria Olbrich’s Secession Building proclaimed the goals of the rebellious group of artists who seceded from the Austrian art establishment in order to embrace avant-garde modern art. They displayed their work inside Olbrich’s building as well as hosting international exhibitions of modern art. The stylized decoration of the building is based on plant forms, while the structure emphasizes the harmonious balance of basic geometric shapes.

The leader of the Vienna Secession, Gustav Klimt, decorated the interior walls of the main exhibition hall with a long decorative mural dedicated to Ludwig von Beethoven. The Beethoven Frieze combines naturalistic representation of the human body, stylized figures, and complex abstract patterns in a variety of materials. Gold leaf and semi-precious stones enhance the decorative quality of the surface, making it a dramatic union of luxurious ornament and figurative painting.

Art Nouveau was fashionable for only a brief period around the year 1900, but the movement was part of a long-term modern trend that rejected historicism and Academicism and embraced new materials and original forms. In the modern period artists and designers increasingly recognized that the health and well-being of society and all its members were supported and enhanced by well-designed objects, buildings, and spaces. The unified designs of Art Nouveau presaged the innovations of the Bauhaus as well as architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier.

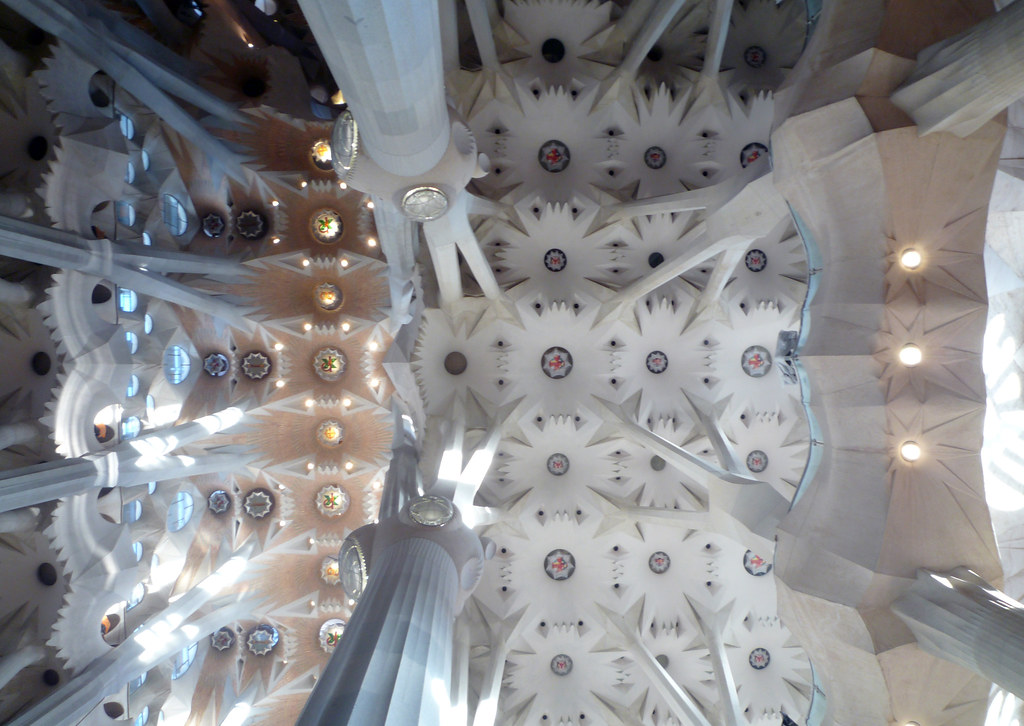

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Família

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\)

120 years and counting

Although Antoni Gaudí was influenced by John Ruskin’s analysis of the Gothic early in his career, he sought an authentic Catalan style at a time, the late 19th century, when this region (currently mostly in northern Spain) was experiencing a resurgence of cultural and political pride. Ruskin, an English critic, rejected ancient classical forms in favor of the Gothic’s expressive, even grotesesque qualities. This interest in the value of medieval architecture resulted in Gaudi being put in charge of the design of Sagrada Família (Sacred Family) shortly after construction had begun.

Gaudí was a deeply religious Catholic whose ecstatic and brilliantly complex fantasies of organic geometry are given concrete form throughout the church. Historians have identified numerous influences especially within the northeast façade, the only part of the church he directly supervised. The remainder of the church, including three of the southwest transept’s four spires, are based on his design but were completed after Gaudí’s death in 1926. These include African mud architecture, Gothic, Expressionist, of course a variant of Art Nouveau that emphasizes marine forms.

The iconographic and structural programs of the church are complex but its plan is based on the traditional basilica cruciform found in nearly all medieval cathedrals. However, unlike many these churches, Sagrada Familia is not built on an east-west axis. Instead, the church follows the diagonal orientation that defines so much of Barcelona, placing the church on a southeast-northwest axis.

The Glory Façade (southeast):

This will eventually be church’s main façade and entrance. As with the transcept entrances, it holds a triple portal dedicated to charity, faith, and hope. The façade itself is dedicated to mankind in relation to the divine order.

The Passion Façade (southwest):

Dedicated to the Passion of Christ, its four existing belltowers are between 98 and 112 meters tall and are dedicated to the apostles James the Lesser, Bartholomew, Thomas and Philip (left to right). Josep Maria Subirachs is responsible for the façade sculpture.

The Nativity Façade (northeast):

Depicts the birth of Christ and is the only façade to be completed during Gaudi’s lifetime. its four existing belltowers are between 98 and 112 meters tall and are dedicated to the saints Barnabas, Jude, Simon and Matthew (left to right).

Ten additional belltowers (98-112 meters high) are planned though these will be overwhelmed by six towers that will be significantly taller. Four of these towers will be dedicated to the Evangelists, one to the Virgin Mary, and the grandest, rising to 170 meters, to Jesus Christ.

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): What Sagrada Familia will look like when construction is complete

Additional resources:

Official site of Sagrada Família

God’s Architect: Antoni Gaudi’s glorious vision, CBS documentary

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

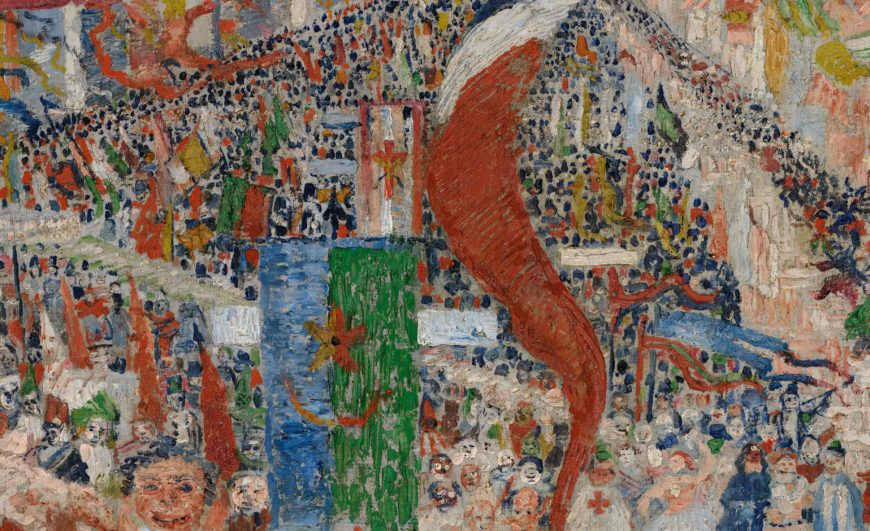

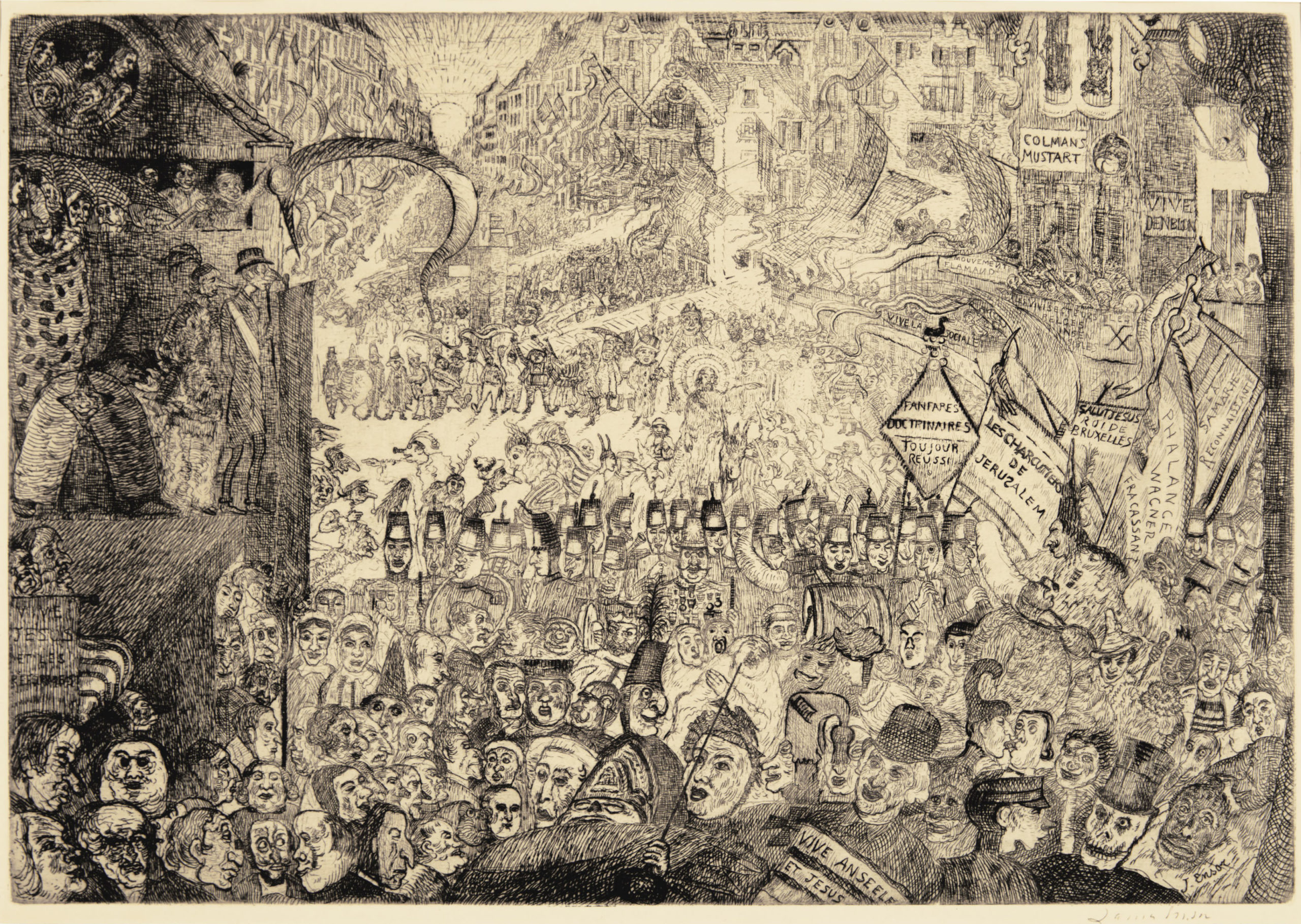

James Ensor, Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 is one of the largest and most ambitious modern paintings of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Over eight feet high and fourteen feet wide, it depicts a huge parade flooding down a wide street toward the viewer. The deep central space framed by reviewing stands and balconies suggests the stage of a proscenium theater. The lurid colors used to paint people, signs, and banners clash, and dozens of grotesque theatrical faces in the crowd, many wearing masks, compete for our attention. In the foreground the raucous mob threatens to spill out of the canvas and sweep us up into the chaos.

The painting’s style and technique are as aggressive as its subject. The paint is applied in crude heavy strokes and slabs to create a rough, heavily-textured surface. Bright red dominates, and it is accompanied by its complement, green, as well as the other primaries blue and yellow. There is no shading, and the overall effect is flat and poster-like. The colors are brighter and lighter in the background, which sparkles with patterns of dots representing the distant crowds and rays of light that criss-cross the waving banners.

Humanity mocked

The painting’s title refers to the traditional subject of Christ’s entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, here transposed to contemporary Belgium. The painting is also reminiscent of the carnival parades of Mardi Gras, the Christian festival that precedes Lent. The small gold-haloed figure of Christ rides a donkey in the center of the painting’s upper portion behind the marching band. He is surrounded by a small group of masked figures whose long noses point up at him, and he raises his arm in a gesture of blessing. Most of the crowd, however, pays no attention to Christ.

Christ’s Entry into Brussels is far from being a conventional religious image of Christ as the savior of humanity. The painting mocks humanity, as well as human beliefs and institutions, both civic and religious. The grotesque parade is led by a bishop dressed in red with a gold miter who is marching out of the painting in the middle of the foreground.

The sea of masks and faces behind him includes priests, government officials, soldiers, a military band preceded by a heavily-decorated leader, and caricatures of many types of ordinary citizens. A masked man dressed in the blue coat and white sash of the city’s mayor watches the parade from a reviewing stand on the right, accompanied by a group of elaborately-costumed masked figures. Ensor himself appears in profile as the yellow-clad figure in the tall conical red hat on the left.

Political critique or personal expression?

A red banner inscribed with the slogan “Vive la sociale” or “Long live the social [revolution]” stretches across the top of the painting and refers to contemporary politics and social reformers. Ensor’s sources for the painting included newspaper photos of an enormous socialist demonstration held in Brussels in 1886. The image of Christ had direct political significance as well; socialist politicians and writers in nineteenth-century France and Belgium frequently portrayed Christ as an exemplary social reformer who worked to improve the condition of the impoverished masses. Ensor is known to have been supportive of liberal social reforms and highly critical of powerful conservative institutions in Belgium, but Christ’s Entry into Brussels does not clearly support any particular political position. On the contrary, it seems to be a wholesale condemnation of both humanity and human ideologies.

Ensor created many works depicting scenes from the life of Christ, some of which were images of suffering in which he portrayed himself as Christ. These self-portraits display Ensor’s sense of persecution as an artist. Although he was a recognized leader among the Belgian avant-garde in the 1880s, he felt unfairly treated by critics and fellow artists. Some of his works were refused by Les XX, the Belgian avant-garde exhibition society he helped to found, and his anger and resentment are evident in many works.

In Christ’s Entry into Brussels, a figure vomits on Les XX’s emblem painted in red on the green balcony above Ensor’s self-portrait.. Thus, among the many topics it addresses, the huge painting expresses Ensor’s personal bitterness toward the art world. It is also often interpreted as symbolically portraying the avant-garde artist as a Christ-like prophet misunderstood by the public.

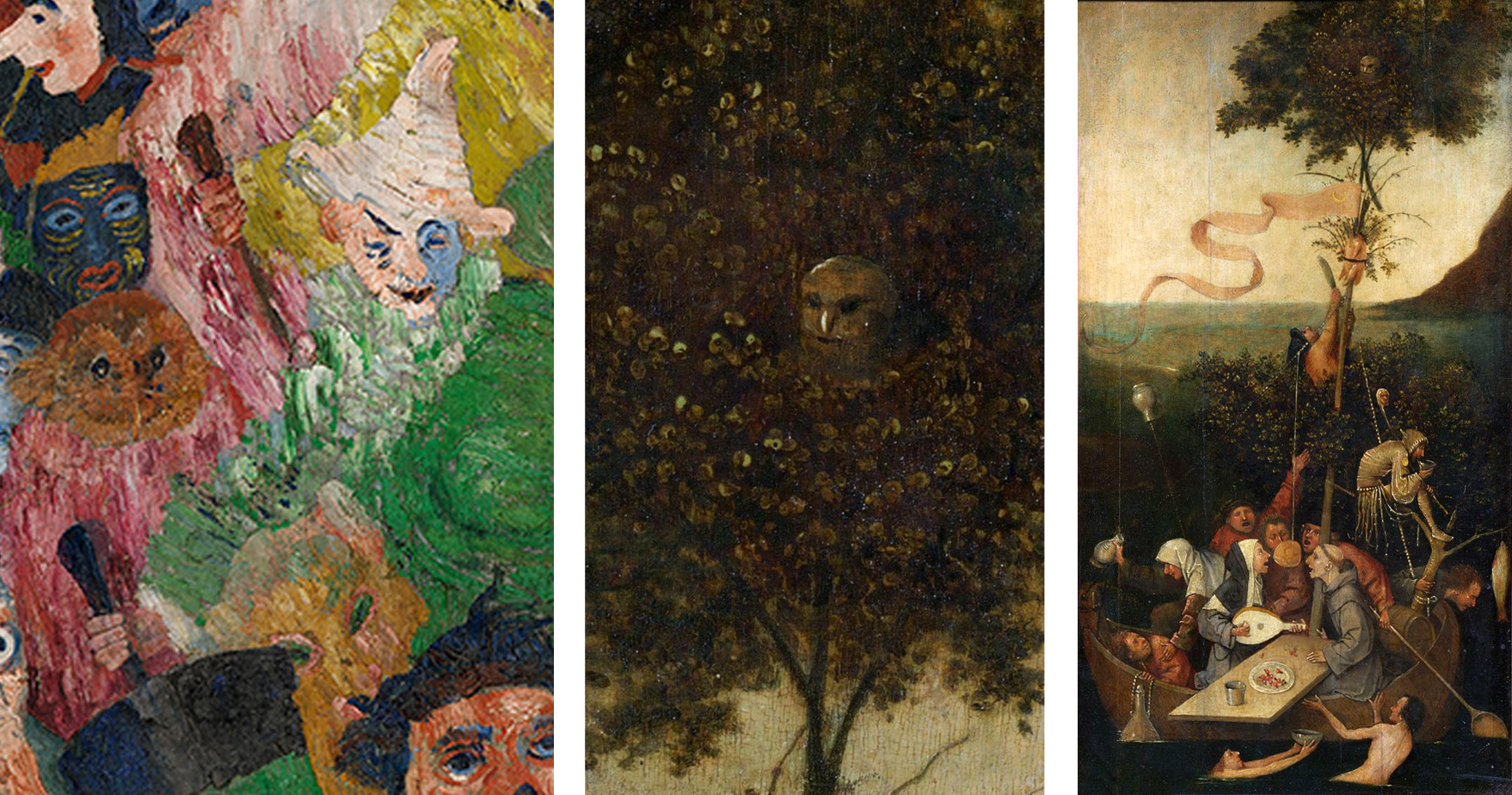

The northern tradition

Ensor painted Christ’s Entry into Brussels when he was twenty-eight. His earliest paintings were Realist and Impressionist in style and subject matter, but in the mid-1880s his work became increasingly idiosyncratic. He adopted subjects associated with prominent artists of the Northern Renaissance and Baroque tradition, including Bosch, Bruegel, Rembrandt, and Rubens. Christ’s Entry into Brussels echoes Bruegel’s Procession to Calvary, a painting in which Christ is also lost in a largely oblivious crowd.

Ensor frequently borrowed fantastic figures and grotesque motifs from Northern Renaissance art, and like Bosch and Bruegel he reveled in the exposure of human folly. In his self-portrait in Christ’s Entry into Brussels Ensor extends his arm down towards the face of an owl, one of many faces in the crowd. While we now associate owls with wisdom, the owl is also a traditional symbol of foolishness. It appears often in this guise in Bosch’s paintings, including his Ship of Fools, where it peers out of the top of the tree.

Masks

The masks that are so prominent in Christ’s Entry into Brussels became a central subject for Ensor in the 1880s. His family owned a curiosity shop that sold papier-mâché Carnival masks in the seaside town of Ostend, making masks both personal and highly symbolic objects in Ensor’s work. Self Portrait with Masks shows him surrounded by a terrifying array of blindly staring masks, but his own portrait is also a sort of mask; it is directly modeled after self-portraits of the great Flemish Baroque painter Peter-Paul Rubens.

In Christ’s Entry into Brussels even apparently unmasked figures have mask-like, caricatured faces suggesting that everyone wears some sort of mask. Ensor’s masked figures represent humanity as superficial, hypocritical, and grotesque. Masks also confer anonymity and allow people to act outside social laws without fear of being recognized and punished.

In Christ’s Entry into Brussels the theme of personal irresponsibility and freedom is enhanced by the association to a Carnival parade. During Carnival, society’s rules are dropped, and the usual social order is turned upside down; rich and poor switch roles, the beggar becomes king or queen for the day. Carnival is often described as serving as a sort of relief valve for the ordinary pressures of society, as well as a moment when underlying truths are exposed. In Christ’s Entry into Brussels the masks can be understood as revealing rather than hiding the true nature of humanity and human society.

Skeletons

Skeletons were another central subject in Ensor’s art, and a skeleton figure wearing a top hat appears prominently in the lower left of Christ’s Entry into Brussels. It adds a macabre reminder of death’s presence in the midst of life, a traditional artistic theme known as memento mori that was very popular in Northern Baroque painting. In numerous works Ensor portrayed skeletons and masked figures in enigmatic scenes that mock the foolishness and cruelty of human behavior. Ensor’s skeletons frequently represent art critics persecuting him.

In Skeletons Fighting over a Hanged Man two skeletons wearing elaborate costumes duel over mannequins using a mop and broom for weapons. Masked figures carrying knives push through the doorways and seem to menace the duelists on both sides. In the left foreground, a third skeleton watches the combat with paintbrush in hand and a palette on his lap, reminding us that for Ensor his paintbrush was both his weapon and his claim to immortality.

Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 is an ambitious and idiosyncratic painting that enlists multiple historical and contemporary artistic sources to address topics that range from the personal to broad social concerns. It was not publicly exhibited until 1929, but prints of it were widely circulated, and Ensor’s highly individualized art influenced many later modern artists, most notably those associated with Expressionism.

Fernand Khnopff

Fernand Khnopff, Jeanne Kéfer

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Fernand Khnopff, Jeanne Kéfer, 1885, oil on canvas (The Getty Center, Los Angeles)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

No photos

Figure \(\PageIndex{66}\): More Smarthistory images…

Franz von Stuck, The Sin

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): Franz von Stuck, The Sin, 1893, 94.5 x 59.5cm (Neue Pinakothek, Munich)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Hector Guimard, Cité entrance, Métropolitain, Paris

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{7}\): Hector Guimard, Cité entrance, Métropolitain, c.1900, painted cast iron, glazed lava, and glass, roughly 14 x 18′, Île de la Cité, Paris

Gustav Klimt

Gustav Klimt, Beethoven Frieze

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{8}\): Gustav Klimt, Beethoven Frieze, 1902, Vienna Secession Hall

The heirs of the Austrian Jewish collector who owned this work before World War II lost their case to recover it in 2015. Learn more in the March 7, 2015 New York Times article.

Gustav Klimt, The Kiss

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{9}\): Gustav Klimt, The Kiss, 1907-8, oil and gold leaf on canvas, 180 x 180 cm (Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna)

Gustav Klimt, Death and Life

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{10}\): Gustav Klimt, Death and Life, 1910, reworked 1915, oil on canvas, 178 x 198 cm (Leopold Museum, Vienna)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch, The Storm

by DR. JULIANA KREINIK and DR. AMY HAMLIN

Video \(\PageIndex{11}\): Edvard Munch, The Storm, 1893, oil on canvas, 36 1/8 x 51 1/2″ / 91.8 x 130.8 cm (Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

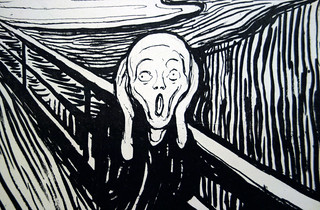

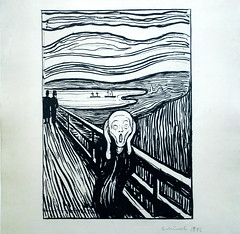

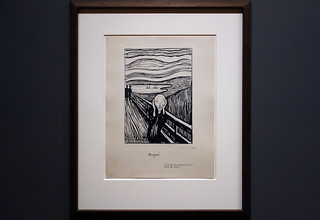

Edvard Munch, The Scream

Second only to Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Edvard Munch’s The Scream may be the most iconic human figure in the history of Western art. Its androgynous, skull-shaped head, elongated hands, wide eyes, flaring nostrils and ovoid mouth have been engrained in our collective cultural consciousness; the swirling blue landscape and especially the fiery orange and yellow sky have engendered numerous theories regarding the scene that is depicted. Like the Mona Lisa, The Scream has been the target of dramatic thefts and recoveries, and in 2012 a version created with pastel on cardboard sold to a private collector for nearly $120,000,000 making it the second highest price achieved at that time by a painting at auction.

Conceived as part of Munch’s semi-autobiographical cycle “The Frieze of Life,” The Scream’s composition exists in four forms: the first painting, done in oil, tempera, and pastel on cardboard (1893, National Gallery of Art, Oslo), two pastel examples (1893, Munch Museum, Oslo and 1895, private collection), and a final tempera painting (1910, National Gallery of Art, Oslo). Munch also created a lithographic version in 1895. The various renditions show the artist’s creativity and his interest in experimenting with the possibilities to be obtained across an array of media, while the work’s subject matter fits with Munch’s interest at the time in themes of relationships, life, death, and dread.

For all its notoriety, The Scream is in fact a surprisingly simple work, in which the artist utilized a minimum of forms to achieve maximum expressiveness. It consists of three main areas: the bridge, which extends at a steep angle from the middle distance at the left to fill the foreground; a landscape of shoreline, lake or fjord, and hills; and the sky, which is activated with curving lines in tones of orange, yellow, red, and blue-green. Foreground and background blend into one another, and the lyrical lines of the hills ripple through the sky as well. The human figures are starkly separated from this landscape by the bridge. Its strict linearity provides a contrast with the shapes of the landscape and the sky. The two faceless upright figures in the background belong to the geometric precision of the bridge, while the lines of the foreground figure’s body, hands, and head take up the same curving shapes that dominate the background landscape.

The screaming figure is thus linked through these formal means to the natural realm, which was apparently Munch’s intention. A passage in Munch’s diary dated January 22, 1892, and written in Nice, contains the probable inspiration for this scene as the artist remembered it: “I was walking along the road with two friends—the sun went down—I felt a gust of melancholy—suddenly the sky turned a bloody red. I stopped, leaned against the railing, tired to death—as the flaming skies hung like blood and sword over the blue-black fjord and the city—My friends went on—I stood there trembling with anxiety—and I felt a vast infinite scream [tear] through nature.” The figure on the bridge—who may even be symbolic of Munch himself—feels the cry of nature, a sound that is sensed internally rather than heard with the ears. Yet, how can this sensation be conveyed in visual terms?

Munch’s approach to the experience of synesthesia, or the union of senses (for example the belief that one might taste a color or smell a musical note), results in the visual depiction of sound and emotion. As such, The Scream represents a key work for the Symbolist movement as well as an important inspiration for the Expressionist movement of the early twentieth century. Symbolist artists of diverse international backgrounds confronted questions regarding the nature of subjectivity and its visual depiction. As Munch himself put it succinctly in a notebook entry on subjective vision written in 1889, “It is not the chair which is to be painted but what the human being has felt in relation to it.”

Since The Scream’s first appearance, many critics and scholars have attempted to determine the exact scene depicted, as well as inspirations for the screaming figure. For example, it has been asserted that the unnaturally harsh colors of the sky may have been due to volcanic dust from the eruption of Krakatoa in Indonesia, which produced spectacular sunsets around the world for months afterwards. This event occurred in 1883, ten years before Munch painted the first version of The Scream. However, as Munch’s journal entry—written in the south of France but recalling an evening by Norway’s fjords also demonstrates—The Scream is a work of remembered sensation rather than perceived reality. Art historians have also noted the figure’s resemblance to a Peruvian mummy that had been exhibited at the World’s Fair in Paris in 1889 (an artifact that also inspired the Symbolist painter Paul Gauguin) or to another mummy displayed in Florence. While such events and objects are visually plausible, the work’s effect on the viewer does not depend on one’s familiarity with a precise list of historical, naturalistic, or formal sources. Rather, Munch sought to express internal emotions through external forms and thereby provide a visual image for a universal human experience.

Additional resources:

This painting on the Google Art Project

Art through Time: The Scream

Short biography of the artist from the J. Paul Getty Museum

Walter Gibbs, “Stolen Munch Paintings are Recovered,” NYTimes, September 1, 2006

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Léon Bakst, “Costume design for the ballet The Firebird”

by THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

Video \(\PageIndex{12}\): Video from The Museum of Modern Art.

Louis Comfort Tiffany

Louis Comfort Tiffany, Vase

by THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

Video \(\PageIndex{13}\): Video from The Museum of Modern Art.

Additional resources:

Louis Comfort Tiffany, Hair Ornament

by THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Video \(\PageIndex{14}\): Louis Comfort Tiffany, Hair Ornament, c. 1904, gold, silver, platinum, black opals, boulder opals, demantoid garnets, rubies, enamel, H. 3 1/4″ / 8.3 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.