6.4: Books in Medieval Europe

- Page ID

- 67077

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Books in medieval Europe

The hand-made books of the Middle Ages are known as manuscripts.

c. 330 - 1300 C.E.

A beginner’s guide to books in medieval Europe

More medieval books survive from the Middle Ages than any other artistic medium.

c. 330 - 1300 C.E.

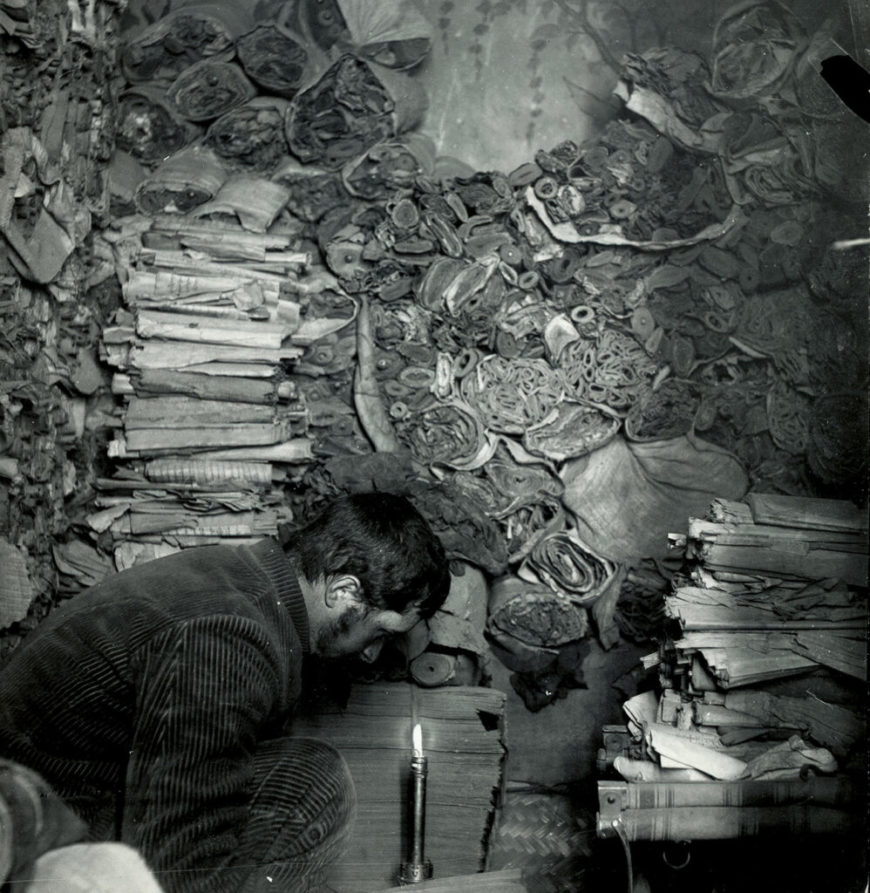

Recording and disseminating information is quick and easy today, but in the Middle Ages this process was slow and laborious. Monastic libraries housed most books and all books were copied by hand, usually by monks. This process of copying and disseminating books was essential to the preservation of knowledge.

Medieval manuscripts, an introduction

What survives

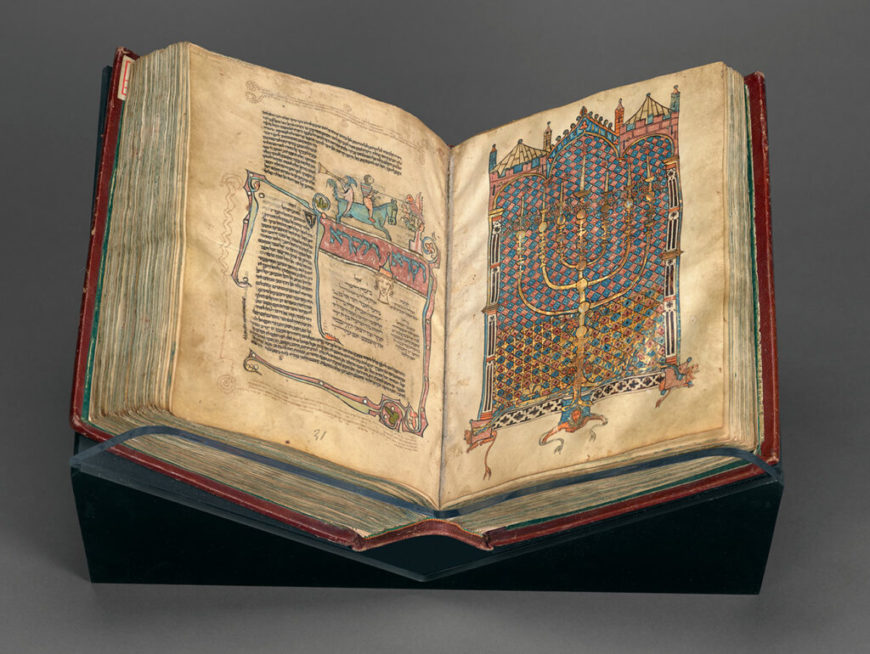

More medieval books survive from the Middle Ages than any other artistic medium. Scholars refer to the hand-made books of the Middle Ages as manuscripts. Books that contain artistic decoration are called illuminated manuscripts. Manuscripts that survive from the European Middle Ages are generally religious books that reflect the canon, doctrine and practices of Christianity, though there are Jewish and Muslim books and other types of books that survive from this time period as well.

The codex vs. the scroll

A medieval manuscript is a codex (pl. codices), meaning a book made of pages bound between two boards. Ancient scribes wrote on scrolls that were stored in boxes. These ancient scrolls only survive in occasional fragments, as a scroll is especially vulnerable to physical degradation. The pages of codices, on the other hand, are protected by their covers and have a much greater chance for survival. Thus, medieval books survive in large numbers.

Where to see medieval manuscripts

The Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris and the British Library in London house the world’s largest collections of medieval manuscripts. Though normally only available to scholars, many museums and libraries put some of their manuscript treasures on display. Digitizing, or creating high quality digital images of manuscripts, is increasingly common and these images are normally available on the Internet, furthering the study of these medieval books.

What’s in the books

The original manuscripts of the Bible, the works of Aristotle and Plato and other ancient writers do not survive. They are known today because medieval scribes diligently copied them.

A slow and laborious process

Recording and disseminating information is quick and easy today, but in the Middle Ages this process was slow and laborious. Monastery libraries housed most books and all books were copied by hand, usually by monks. This process of copying and disseminating books was essential to the preservation of knowledge.

Some monks traveled to distant monasteries to view and copy books to bring back to their own monastery’s library. Fires destroyed many medieval libraries and the books they housed. Because of this and other accidents of history, not all texts survived the Middle Ages. The Name of the Rose, a novel by Umberto Eco, imagines such a fate for Aristotle’s lost work on poetics.

Books & Christianity

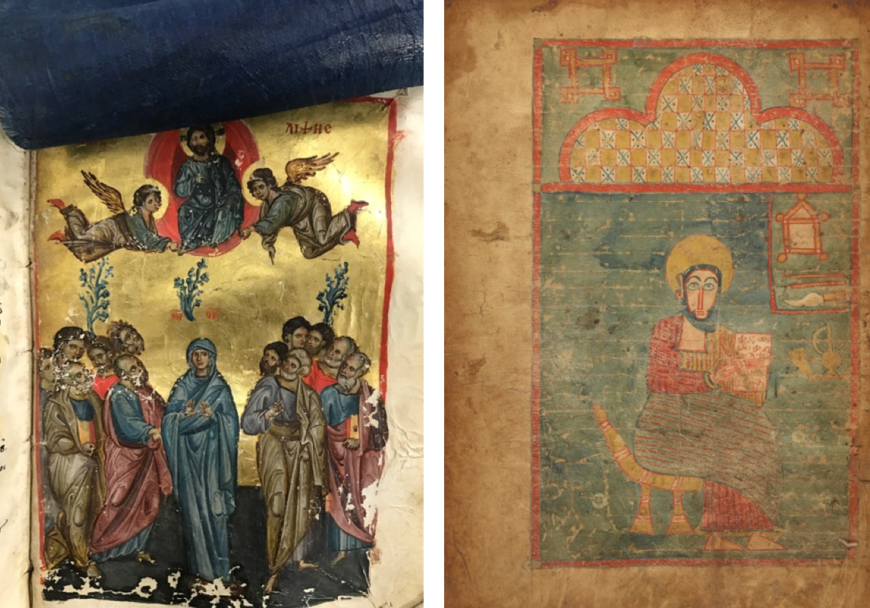

Books were essential to the practice of Christianity. Medieval Christian missionaries, such as St. Augustine of Canterbury, brought books with them as they traveled from place to place preaching and establishing new churches. The Gospel Book of St. Augustine survives today in the Parker Library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. It contains the text of the gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke and John of the New Testament—an essential work for teaching potential converts about the life of Christ. A series of images illustrating the life of Christ prefaces the text and each book of the gospels begins with an illustration detailing the events unique to that gospel, though some of these are now lost.

Illustrations

The oldest illuminated manuscripts are among the oldest manuscripts in existence. The illustration of books was functional as well as decorative. Illuminated initials and painted miniatures marked the beginnings of important sections in the text and allowed readers to navigate the book.

Prefatory image cycles prepared the mind of the reader to engage with the text. Some illustrations elaborate doctrines, record events or simply tell stories. Even readers’ doodles are intriguing to contemporary scholars.

Word and image

In illuminated manuscripts, words and images worked together to inform the medieval reader and occasionally these readers left their own mark. These books are highly interactive. Nearly all medieval manuscripts provide ample space in the margins for readers’ notes and comments. In this way, illuminated manuscripts are different from other types of media in that they provided spaces for readers to record their reactions to image and text.

Manuscripts: major works of art

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Video from the J. Paul Getty Museum

Making manuscripts

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Video from the J. Paul Getty Museum

The Bestiary

A book of beasts

Have you ever heard that elephants are afraid of mice? Or that foxes are deceptive? These characterizations of animals come from a medieval book called the Bestiary, or Book of Beasts. Though these books are not known to many today, you are likely familiar with some of their content. The magical beasts in the Harry Potter series come directly from medieval bestiaries. Descriptions of unicorns, phoenixes, basilisks, and centaurs are all included in the text, but misspell “bestiary” in a Google search and you will likely regret it.

The Bestiary is a medieval encyclopedia that identifies a selection of animals, plants, and precious stones. Some really exist in nature and others do not. Each entry includes a physical description, an overview of the animal’s supposed characteristics, and a run-down of its moral qualities. Many versions of these books include illustrations. Its worth keeping in mind that Bestiaries pre-date the printing press. They were copied by hand at different times and places, resulting in a wide range of variations.

From a Christian perspective

The lack of scientific information in each entry makes them entertaining to read. For example, the Bestiary text describes the beaver as a gentle animal whose testicles are valued for their medicinal properties. If a beaver senses that he is being hunted, he will bite off his testicles and throw them to the hunter to save his own life. If a beaver has already done this and is hunted again, he will stand on his hind legs and show the hunter that his testicles are already missing and the hunter will let him go. The text then goes on to give a Christian moralization of the beaver, stating that “every man who heeds God’s commandment and wishes to live chastely should cut off all his vices and shameless acts, and cast them from him into the face of the devil” (source).

Sources

The Bestiary text is made up of several components. The bulk of the text comes from the Physiologus, a second century Greek text by an anonymous author. Relevant comments by other ancient authors such as Aristotle, Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, and Aelian are also included. The Etymologiae of Isidore of Seville, the late fifth and sixth century Archbishop, constitute a significant portion of the text. Layers of Christian commentary and moralizations were added to those earlier texts.

Content

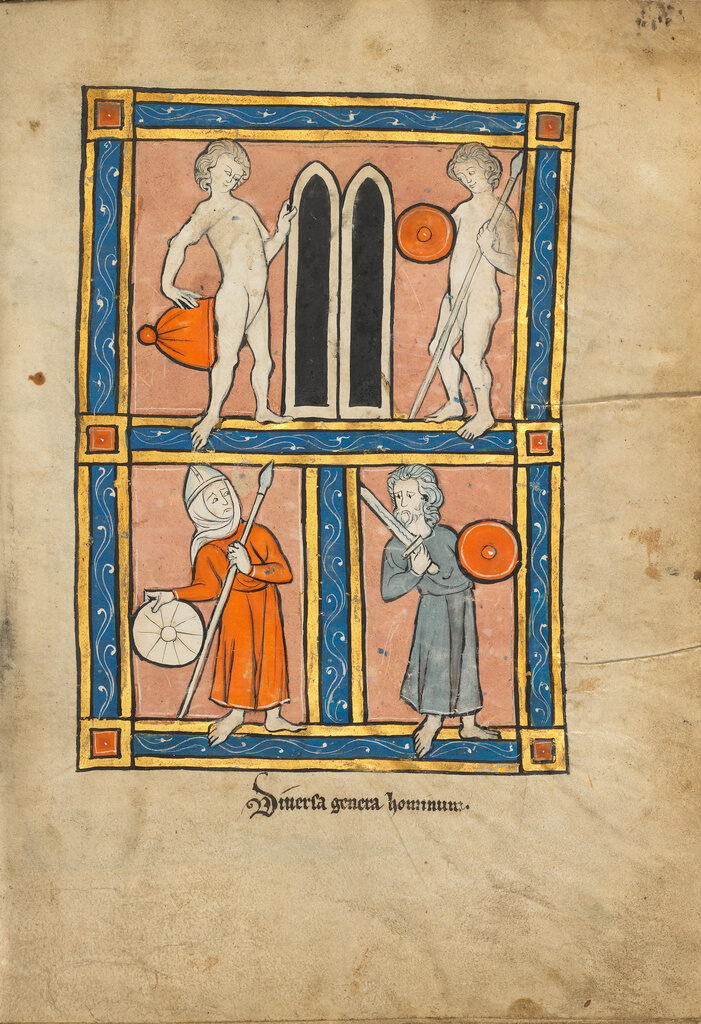

The Bestiary begins with a retelling of the creation story from Genesis. An important event is Adam, the first man, naming all of the animals. This scene is often included in illustrated Bestiaries. Isidore of Seville believed that the names of animals were significant. He believed that an etymological study of each animal’s name would reveal something about the nature of each animal.

The content of the Bestiary, particularly the moralizations on the animals, is echoed in many medieval texts, from sermons to stories. Chaucer’s “Nun’s Priest’s Tale,” an animal story from the Canterbury Tales, makes use of the Bestiary. The main characters are a sly, deceptive fox and Chanticleer, a foolish and egotistical rooster.

Illustrations

The Bestiary was an enormously popular book in the Middle Ages and more than 130 medieval copies survive today. These copies come from all over Western Europe. The earliest manuscripts date from the tenth century and many survive from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Many illustrations were drawn by artists who had never seen the relevant animal, but used the physical descriptions as a guide. The Bestiary text was influential, but these portable illustrations of animals were equally influential and likely served as models for animals in other manuscript illustrations, stone carving, wall painting, stained glass, and other media.

A Global Middle Ages through the Pages of Decorated Books

Manuscripts and printed books—like today’s museums, archives, and libraries—provide glimpses into how people have perceived the Earth, its many cultures, and everyone’s place in it. Toward a Global Middle Ages: Encountering the World through Illuminated Manuscripts, a new book from Getty Publications, invites you to explore this theme, presenting a range of book types from premodern Africa, Europe, Asia, the Americas, and Austronesia.

The production of books is a collaborative undertaking. In the premodern period, this process could involve the makers of writing surfaces, binding supports, scribes, procurers and creators of pigment, merchants, artists, patrons, and eventually the readers, viewers, or listeners. Toward a Global Middle Ages includes essays by twenty-six authors who are specialists of the art of the book.

Whose Middle Ages?

What do we mean by a global Middle Ages (or medieval period)? Writing about the Middle Ages has traditionally centered on the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim communities in Europe, Western Asia, and the greater Mediterranean between the years 500 and 1500. The term “Middle Ages” was used in the nineteenth century to describe a medium aevum, a middle age between the Roman Empire and the Renaissance.

For decades, scholars have challenged this Eurocentric view of the past, turning attention to a global Middle Ages that includes Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Austronesia. Some of these scholars seek to uncover networks, pathways, routes, or links between people and places. In doing so, an aim has been to reveal the lives of those who have been silenced by history or tradition: women, enslaved individuals, Indigenous peoples, queer or disabled groups. Others take a comparative approach, examining similar phenomena in different places at the same time or over time. Toward a Global Middle Ages expands upon these perspectives.

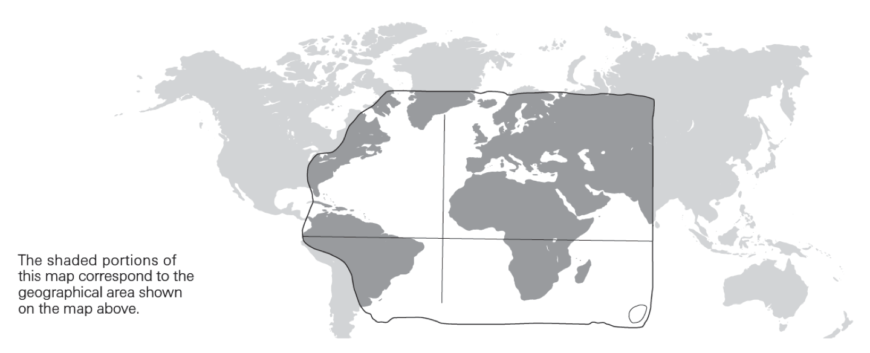

There are also discussions about the meaning of “global” at a local level, and whether it is possible to speak of early globalities prior to the sustained transatlantic contacts between Europe, the Americas, and Africa in the late fifteenth century (it should be acknowledged that the latter view still largely centers on Europe—as indicated below and in the volume, peoples of northeastern China and Siberia had contacts with First Nation peoples, including those who inhabited the Aleutian Islands).

Some scholars select a hemispheric focus—referring to a hemispheric Middle Ages—that concentrates on Africa, Europe, and Asia on the one hand, and the Americas on the other. With this approach, we can still find connections through comparisons if we look to astronomy or astrology, for example, as I discuss in Toward a Global Middle Ages and have outlined briefly before; we might also consider global climate change (evidenced through ice cores and testimony from manuscripts or oral traditions) and the spread of diseases or the relationship between botany and linguistic development of words for popular trade goods, such as sweet potato or tea. Whichever methodology seems most applicable to the scope of a given study, one recommendation is to continually resist Eurocentrism and to cross boundaries—of periodization, discipline or specialization, historical or present-day geography, language (of documents and of academic training), and so forth.

It takes time to redirect the writing of history. The authors of this book therefore describe what we do as working toward a global Middle Ages.

Paper, Parchment, and Palm Leaves

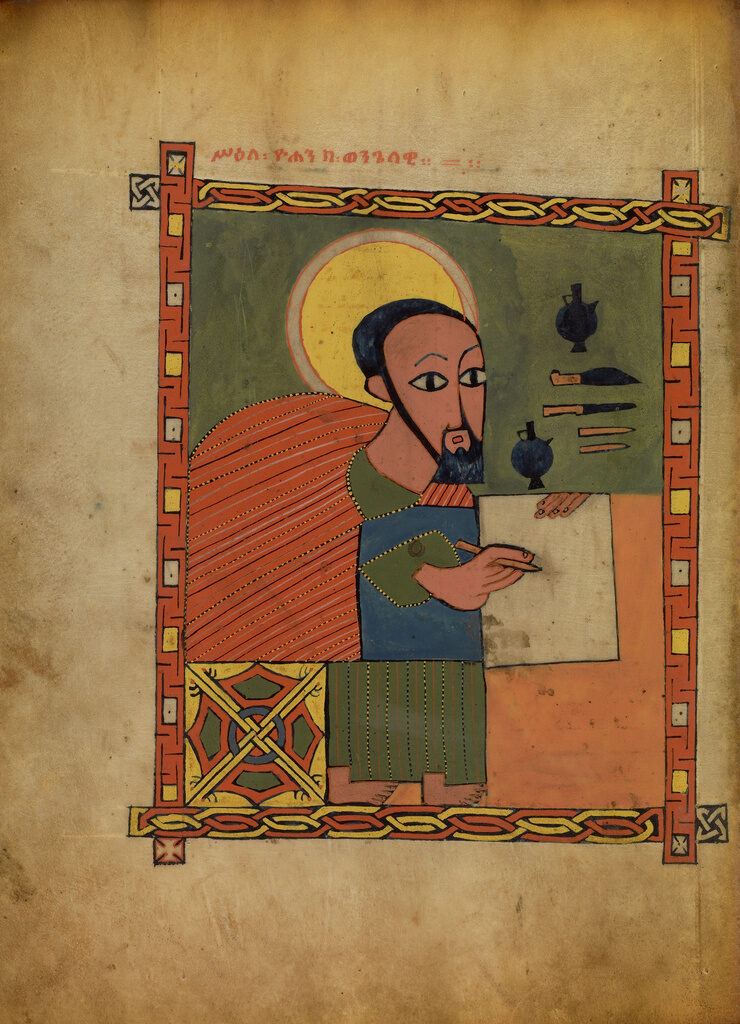

Books were key modes of cultural expression and exchange throughout the Middle Ages. Manuscript means “handwritten,” from the Latin words manus (“hand”) and scriptus (“written”). Lavish examples were often embellished with metallic leaf or paint that shimmered in the light, which gives us the term “illuminated.” Print technology allowed images and texts to be replicated, and some global traditions combined manuscript and print.

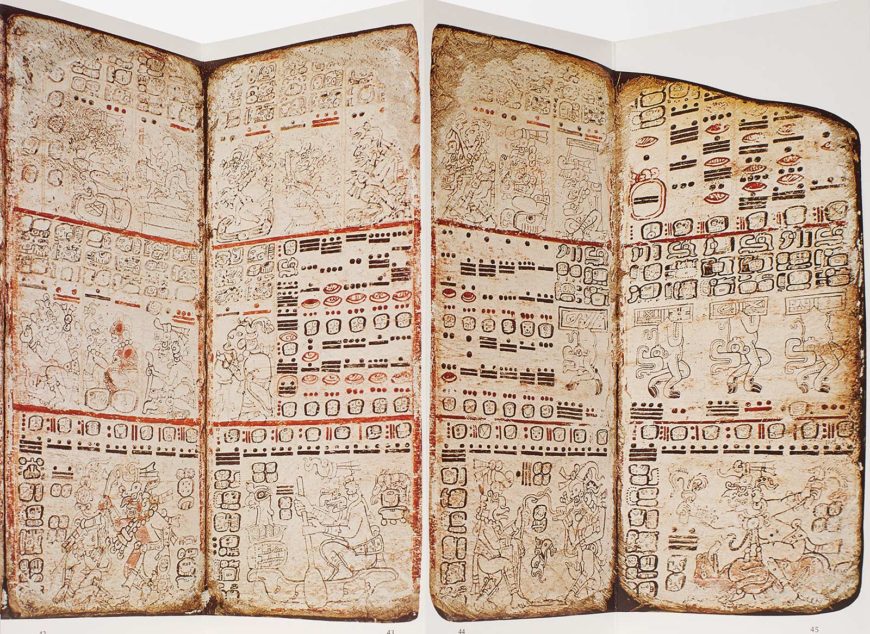

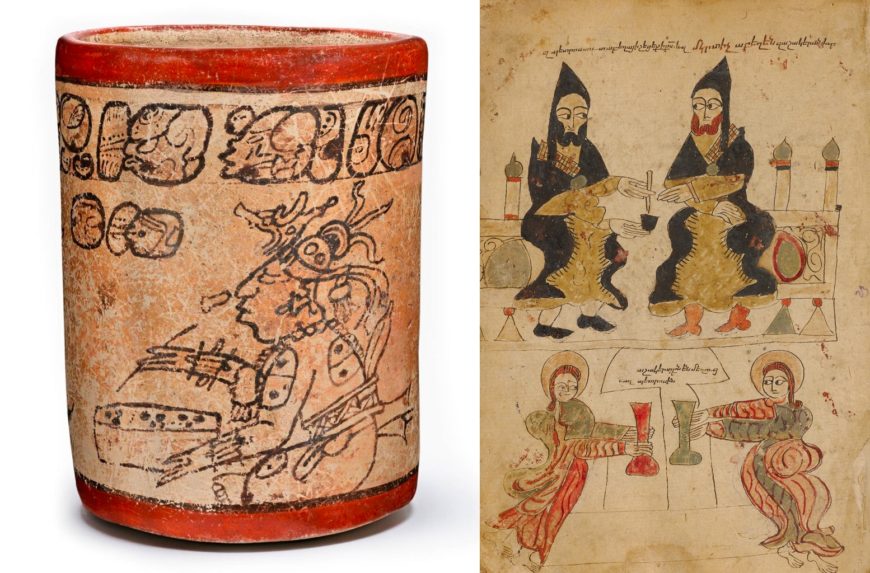

Across Afro-Eurasia, the Americas, and Austronesia during the medieval period, bookmakers used a variety of supports and structures, including paper, parchment, and palm leaves. Each of these could be gathered together in various ways: bound as a codex, rolled as a scroll, or folded as an album. In some instances, we have to look at other types of artworks for glimpses of book or writing traditions (as with the Maya, whose long history of codex creation was decimated by the Spanish conquest yet ceramic vessels provide evidence for early manuscript production in Mesoamerica). The examples shown in this post hint at the diversity of book types and formats.

Manuscripts and books operated alongside other forms of literacy and visual storytelling throughout the Middle Ages. These include glyphic and graphic examples—characters or symbols carved or painted onto a surface, such as stone, ceramic, or the body—as well as oral traditions and memory aids. Such varied objects shed light on the many ways in which the book, broadly defined, functioned in multiple contexts in the past, and on the relationship between the visual arts and language, storytelling, and the commemoration of the past.

A World Without a Center

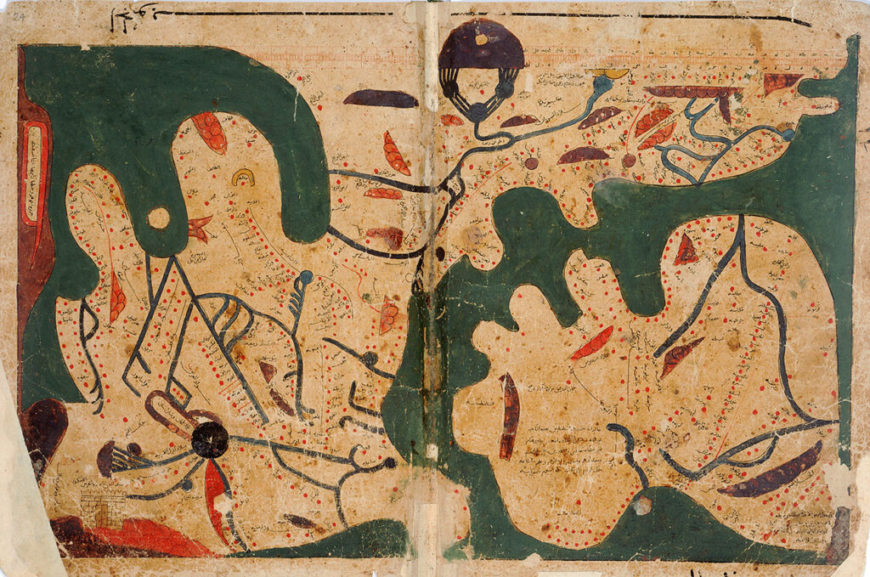

Maps are another focus of the new publication. Like manuscripts, maps present world views, including views of self and others; they also change frequently and are often political.

Fascinating parallels emerge when looking at maps across cultures. The 11th-century “Book of Curiosities” from Egypt, for example, describes legendary peoples and creatures that also appear in a 13th-century European compendium of Latin texts. The Ottoman admiral-mapmaker Piri Reis and the Korean scholar Kwon Kun created maps that include portions of the Americas (Brazil and the Aleutian Islands of present-day Alaska, respectively).

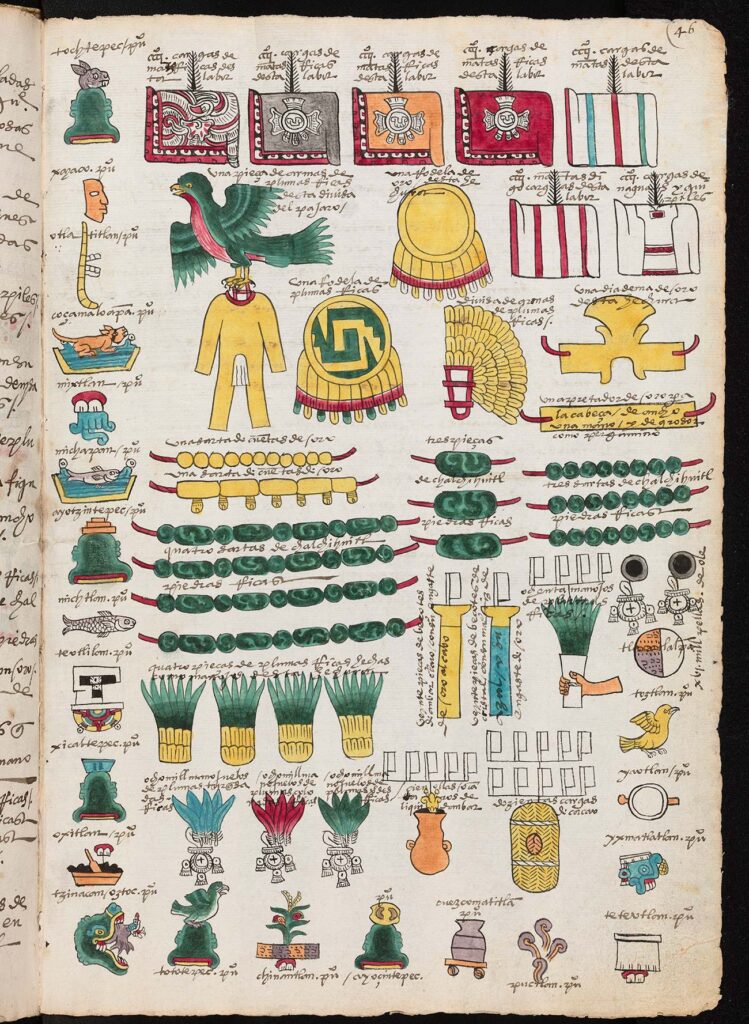

Mapping can also take many forms. On the Shoshone-Bannock Map Rock in Idaho, for example, Indigenous mapmakers charted astrological and geographic information onto the surface of rocks. The 1542 Codex Mendoza features a Nahua map of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan and visualizes the tribute from the provinces as luxury items of jade and feathers.

Through these and many other examples of maps, manuscripts, and related book arts, Toward a Global Middle Ages demonstrates that geographic and cultural boundaries were and are porous, fluid, and permeable.

My co-authors and I hope this new book contributes to the vibrant conversations about a global Middle Ages, and to the role of manuscripts and visual culture in these conversations. I welcome comments and questions about the book and its themes, and particularly hope it can be of use to instructors and students—see the resource list below, prepared with research and classroom use in mind.

This essay first appeared on the iris (CC BY 4.0).

Additional resources

Download a resource list for Toward a Global Middle Ages, including the table of contents, related Getty online resources, and a list of manuscripts and books discussed in the book.

Toward a Global Middle Ages: Encountering the World through Illuminated Manuscripts, ed. Bryan C. Keene (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019)

Catherine Holmes and Naomi Standen, “Introduction: Towards a Global Middle Ages,” Past & Present, vol. 238 (November 2018), pp. 1–44

Visions of Paradise in a Global Middle Ages

The word “paradise” often describes an idyllic place of unmatched beauty, but it can also refer to a mindset of harmony and bliss. Several world religions share these conceptions of paradise, but the paths for locating it—whether in a physical environment, a metaphysical realm like heaven, or a state of transcendence—have varied greatly. The image above shows the blue-skinned Hindu deity Krishna (an incarnation of Vishnu, “the preserver”) transplanting the sacred parijata tree from heaven. He carries the plant to earth along with his wife Satyabhama, who ride together atop an eagle-like mythical being called Garuda. At right, the many-eyed god Indra and his consort witness the event.

The exhibition Pathways to Paradise: Medieval India and Europe (2018) presented a selection of illuminated manuscripts and luxury objects from Asia, Africa, and Europe that communicate the spiritual quests of individuals who sought sacred groves, providential gems, and guides to enlightenment. This essay introduces several of the objects from the exhibition.

A Global Middle Ages

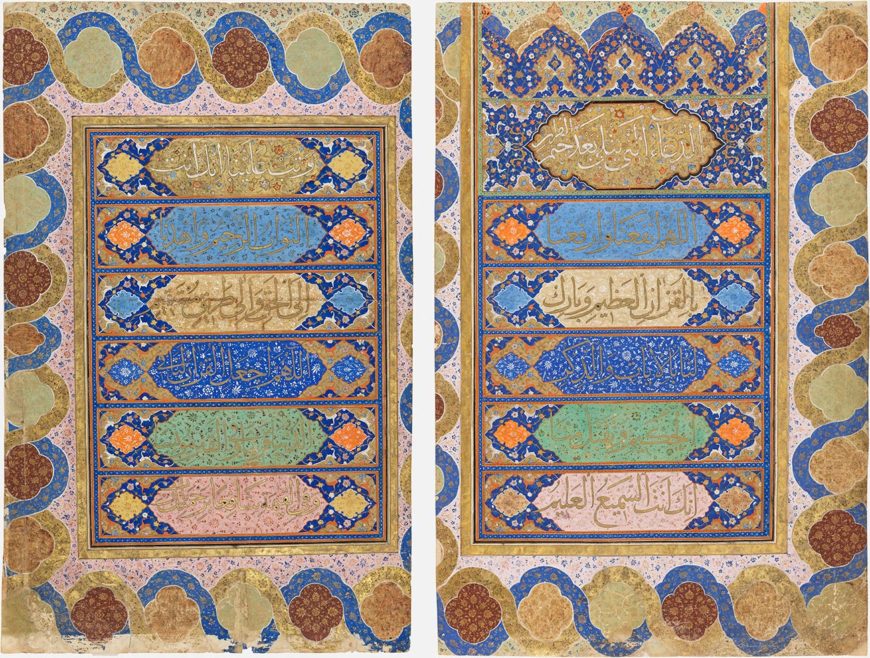

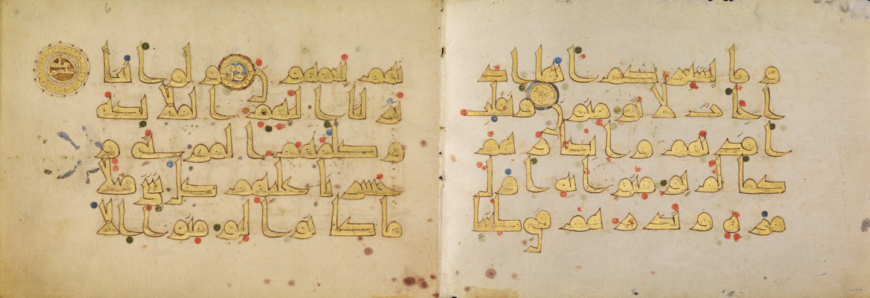

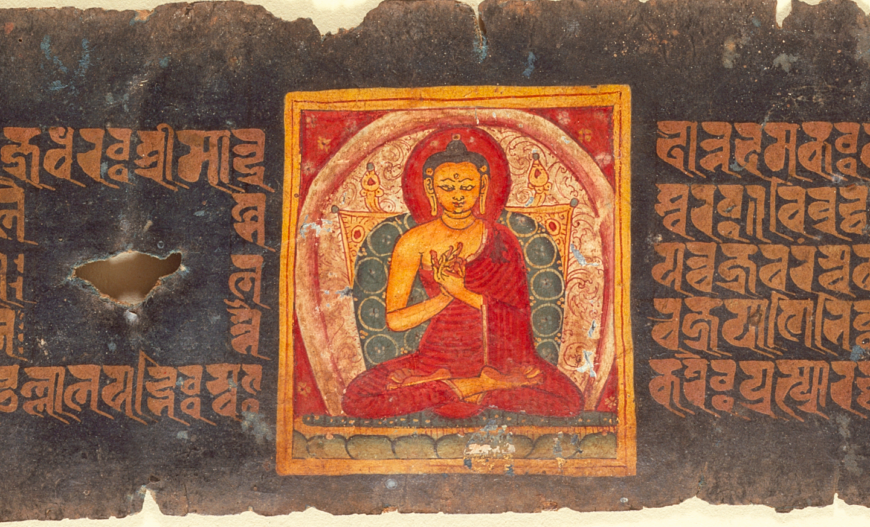

The majority of the manuscripts in the Getty’s collection were produced in Western Europe from the ninth through the sixteenth century, with additional examples from important centers of the Byzantine world (the Eastern Roman Empire), Armenia, Ethiopia, and elsewhere. Exhibitions allow us to expand the traditional narratives about a European Middle Ages to consider a global Middle Ages of trasnational connections. By doing so, our holdings of a ninth-century Qur’an from Tunisia (above), a silk veil in a thirteenth-century Byzantine Gospel book, and a page from a fifteenth-century Gospel book from Ethiopia (both below) find new relationships alongside leaves from Buddhist manuscripts on loan from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art—all of which include areas painted or dyed with the blue pigment indigo, which was largely sourced in India at the time.

Empires in the Indian subcontinent, the Hindu Kush, and the Tibetan or Himalayan Plateau shared intertwined histories with principalities to the west, from the Greeks and Romans to the Persianate, Christian, and Islamic kingdoms of Central Asia or East Africa. Similarly, peoples throughout Europe and the Mediterranean had contact with and developed imagined ideas about the land of India—its peoples, religions, and natural wonders—since ancient times. Art from Gandhara (present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan), for example, combined elements from Greece, Rome, Persia, and local traditions, demonstrating the long history of contact at this crossroads of civilizations.

In the exhibition, a beautifully carved Gandharan head of a bodhisattva—an enlightened follower of the Buddha who helps others reach Nirvana (release from cycles of desire and suffering)—greets visitors upon entering the gallery. A mostly complete statue from the Norton Simon Museum gives a sense of the various cultural influences (the bodhisattva Maitreya wears a Greco-Roman style toga), and a relief from LACMA shows Buddha Shakyamuni seated near a Corinthian column, another instance of Roman inspiration.

The Middle Ages (about 500–1500) witnessed increased movement between Europe, Byzantium, the Islamic world, and India. One of the historical figures whose legacy links these cultures is Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.E.), whose military campaigns took him from Macedonia to Northwest India. This range explains some of the transculturation in art from regions like Gandhara. Few contemporary accounts survive about the Macedonian world ruler, but classical and medieval writers in Europe, Central Asia, and India preserved his memory through histories, chronicles, and romances.

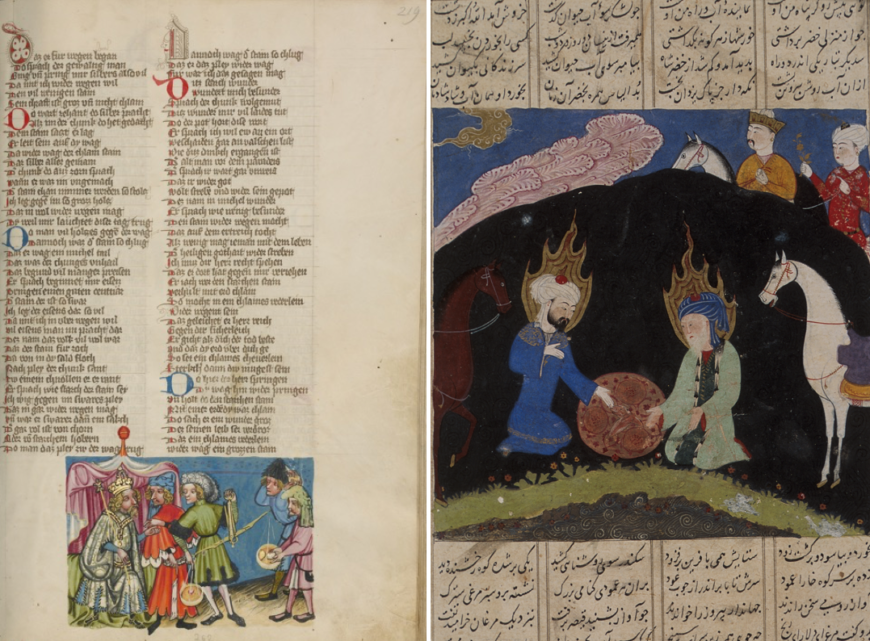

Rudolf von Ems (about 1200–1254) based this German World Chronicle on Roman sources, which cast Alexander as an ideal ruler from “the East.” According to the text, Alexander sought the mythical earthly paradise during his military campaigns across Asia. On one journey, an elderly man presented the ruler with a precious gem said to be from paradise, which weighed more than any other jewel. When the stone was ground into a powder, it became light and worthless. The message to Alexander was that his reign would be great in life but forgotten in death, a paradox given his enduring fame today.

The cross-cultural legacy of Alexander the Great is also present in a fifteenth century Persian text from Iran called the Khamsa of Nizami (1141–1209). Following military campaigns in Eastern Africa, India, and China, the world-ruler Iskandar (Persian for Alexander the Great) began a journey to find the Fountain of Immortality. Nizami wrote that the magical youth-granting waters flowed from the North Pole. The prophets Khizar and Ilyas guide Iskandar through a place called the Land of Gloom or Darkness but they also conceal the stream of the Fountain. The rich traditions for illuminated manuscripts about Alexander/Iskandar connected distant regions of Eurasia from ancient to Early Modern times, especially episodes about his more fantastic exploits or encounters, such as his journeys under the sea or into the sky.

Mapping the Premodern World: A View from Europe

A nearly-five-foot-long map designed by cartographer Vesconte Maggiolo (1478–1530) in 1516 provides a point of connection. From India and Central Asia in the East to the Caribbean and the Americas to the West, the map presents an extensive view of the world as understood by a man living in Naples in the early sixteenth century (explore a high-resolution version of the map here).

Across Afro-Eurasia, Vesconte Maggiolo depicted tents and enthroned rulers to mark the major kingdoms known to him, including Morocco, France, and Persia. Multicolored islands indicate fabled sites of gem mining, silk production, and the spice trade, all of which derive from a long literary and visual tradition in the Mediterranean. A roundel of the Virgin and Child, situated in the Atlantic Ocean near several ships returning to Europe, suggests the missionary and mercantile agendas of the period.

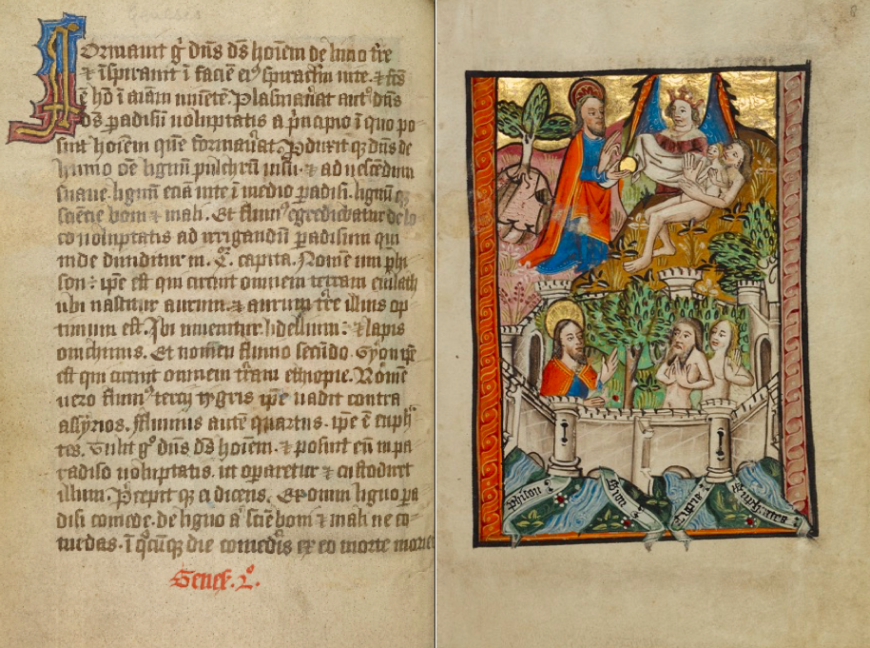

On the map, the earthly paradise known as the Garden of Eden emerges in the kingdom of Prester John, a mythical Christian king shown here in Africa (in the vicinity of Ethiopia) but who was also associated with India or lands farther east. The biblical book of Genesis describes the paradisiacal garden at the source of four rivers: the Pison (possibly in Syria), the Gihon (said to be in Ethiopia), and the Tigris and Euphrates (in ancient Mesopotamia, primarily in present-day Iraq). The artist of a devotional manuscript made in East Anglia, England labeled the rivers and showed them surging forth from a walled orchard where God placed Adam and Eve.

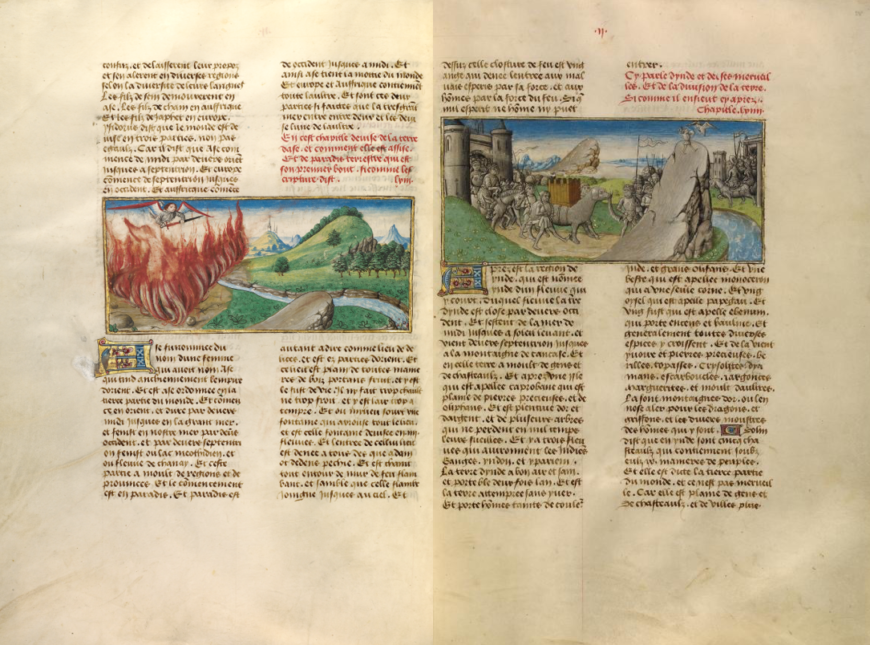

The Dominican writer Vincent of Beauvais (1184–1264) wrote a comprehensive world history that began with the biblical creation story and extended to the year 1254. He derived his knowledge of the East from a range of sources, including the Roman author Solonius (third century) and the Franciscan missionary John of Plano Carpini (about 1185–1252). Accordingly, Vincent of Beauvais locates the Garden of Eden not in Ethiopia but beyond the land of India and the Island of Taprobane (Sri Lanka). In other words, paradise was a place that was virtually inaccessible in the spatial imagination of sedentary writers, readers, and viewers in Europe.

Based on the descriptions in the text, the illuminator rendered an elephant, a griffin, and blue-skinned people wearing indigo-dyed clothing. Additionally, the author mentions exports from East Asia that include spices and ivory, as well as gems believed to come from the rivers of paradise (the detail shows purple, red, and green jewels within one of the rivulets). The relationship between gems and India is a theme explored in the exhibition through a range of objects produced from the Rhine-Meuse region in Europe to Jammu and Kashmir in India.

Infinite Gems: The Auspicious Çintemani

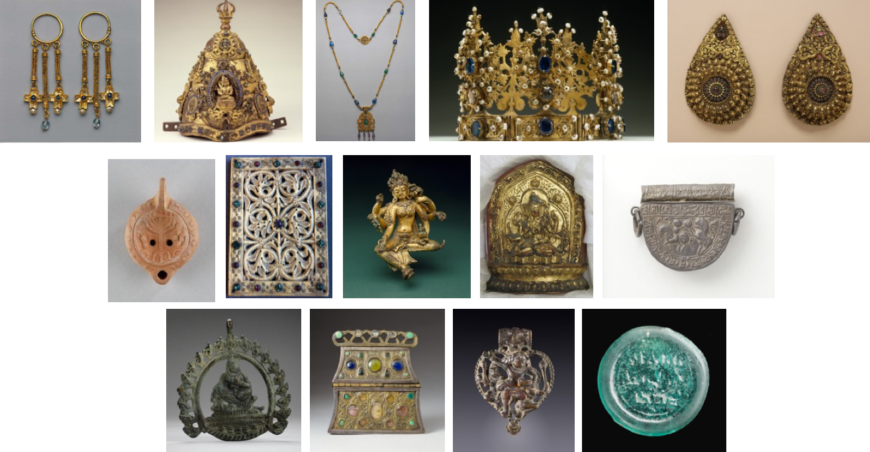

People, manuscripts, and luxury items moved with considerable frequency throughout the premodern world. An ivory plaque (middle row, below, second from left), for example, likely came from the tusk of an African elephant, and once carved, it adorned the cover of a Gospel book from Central Europe. The colored glass pieces were likely meant to simulate rubies and emeralds, precious gemstones often sourced from Central Asia and India, and which symbolically referred to descriptions of Heavenly Jerusalem in the Book of Revelation.

Other raw materials such as sapphires, turquoise, gold, and silver were especially prized trade goods. Many cultures and religions ascribe magical or healing properties to gems or metals, and these associations often involved ideas about the divine and the afterlife. While some precious goods—such as jewelry, amulets, and reliquaries—were highly portable and therefore had the potential to traverse great distances, other objects—including crowns, oil lamps, and votive statues—could serve local audiences at court, in temples, or in shrines.

Buddhist priests in Nepal, for example, wore crowns shaped to recall the division of the universe into earth, atmosphere, and heaven, a cosmological theme complemented by gem settings. A small gilt copper votive sculpture of the Buddhist goddess Vasudhara, bejeweled with semiprecious stones, holds grain, a waterspout, a gem, and a sacred manuscript, all symbols of paradise and prosperity.

Stories from the life of the Buddha reached European audiences through a lengthy process of translation from Sanskrit to Arabic, Georgian, Greek, and eventually Latin and German. Vignettes from the life of the Indian “enlightened one” became part of the hagiography of Christian Saints Josaphat and his spiritual mentor, Barlaam (The name Josaphat derives from the Sanskrit word bodhisattva). The author Rudolf von Ems (c. 1200–1254) wrote that an Indian prince called Josaphat meditated beneath a tree after witnessing illness, old age, and death for the first time, having lived his entire life until that point in a palace. In a sacred grove, Josaphat met the Christian missionary and merchant Barlaam, who offered Josaphat a precious gem (known as the çintemani in Sanskrit or the triratna in Pali).

In a thirteenth-century Tibetan Ashtasarika Prajnaparamita (The Perfection of Wisdom) manuscript, the çintemani design of three dots can be seen in the background of all three pages, as well as on the cloth that extends from the Buddha’s throne (at top). The same pattern can be seen on the thirteenth-century Nepalese Paramartha Namasangiti manuscript shown above. The concept of a wish-granting or protective jewel originated in Hindu and Buddhist sacred texts, but eventually, the motif became a favorite pattern on luxury textiles throughout the Persian Empire, the Islamic world, East Asia, and Europe. As medievalist Jaroslav Fulda has demonstrated, representations in sculpture can be found on the Sasanian tombs at Naqsh-e Rustam, northwest of Persepolis, Iran, and the textile pattern was represented on garments of holy figures as early as the ninth century in the Book of Kells.

I have also found pictorial depictions of the design in Buddhist paintings from Dunhuang to Tibet, Bihar, and elsewhere. The borders around the Prajnaparamita scenes are closely related to cotton and silk textiles from India and the Islamic world, specifically in Persia, suggesting that the çintemani pattern was transmitted by way of the sericulture trade. In the exhibition, a selection of objects highlight these global connections.

In Nepal, Çintemani Lokesvara is one of the many forms of the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, who represents compassion. He grasps in one hand the wish-granting gem—the çintemani—and with the other welcomes all devotees, who would have visited the sculpture in a shrine. A fragment of a dress or furnishing fabric with the çintemani design from Bursa or Istanbul is a focus point in the exhibition—the silver metallic threads on gold and crimson silk satin is truly stunning.

With twenty manuscripts, over twenty coins, fifteen luxury objects, three sculptures, and a textile, the exhibition included numerous potential pathways to paradise. I encourage you to reflect on your own ideas about how to achieve a state of absolute perfection in a busy world.

This essay was first published on the iris (CC BY 4.0)

Additional resources:

Sheila Blair and Jonathan Bloom. Images of Paradise in Islamic Art (Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College 1991)

Bryan Keene, Gardens of the Renaissance (J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013)

Bryan Keene, ed. The World in a Book: Manuscripts and a Global Middle Ages (J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019)

Bryan Keene and Morgan Conger, “Sestieri al paradiso: l’India e l’Europa nel Medioevo,” in Alumina Pagine Miniate, no. 60 (Jan.-Mar. 2018), pp. 50-57

James McHugh, “The Incense Trees of the Land of Emeralds: The Exotic Material Culture of Kamasatra,” in the Journal of Indian Philosophy, no. 39 (2011), pp. 63-100

James McHugh, “Gemstones,” in Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism, ed. Knut A. Jacobsen, Helene Basu, Angelika Malinar, Vasudha Narayana (2012)

Pratapaditya Pal, Art of Nepal: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection (1985)

Pratapaditya Pal, Indian Paintings: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection (1993)

Pratapaditya Pal, Puja and Piety: Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist Art from the Indian Subcontinent (2016)

David T Sanford, “Identification of Three Miniatures in the Nasli and Alice Heeramaneck Collection,” in Artibus Asiae, vol. 32, no. 1 (1970), pp. 42–47

Alessandro Scafi, ed. The Cosmography of Paradise: The Other World from Ancient Mesopotamia to Medieval Europe (Warburg Institute 2016)

Making the medieval book

For much of the Middle Ages dead cows were the main ingredient for books. What was frolicking in the meadow one month, may have been a page in a Bible the next.

Listening to the medieval book

by DR. ERIK KWAKKEL and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Boethius, De institutione arithmetica, c. 1100, The Hague, Royal Library, MS 78 E 59 and Paris Bible, mid 13th century, The Hague, Royal Library, MS 132 F 21. Special thanks to Ed van der Vlist, Curator of Medieval Manuscripts, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, National Library of the Netherlands.

An introduction to medieval scripts

by DR. ERIK KWAKKEL and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Can you tell the difference between Carolingian Minuscule and Gothic script? Watch this video and you’ll learn how.

A medieval textbook

by DR. ERIK KWAKKEL and DR. BETH HARRIS

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Boethius, De institutione arithmetica, c. 1100 (The National Library of the Netherlands, The Hague, MS 78 E 59)

Special thanks to Ed van der Vlist, Curator of Medieval Manuscripts, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, National Library of the Netherlands.

Parchment (the good, the bad, and the ugly)

Parchment

For much of the Middle Ages dead cows were the main ingredient for books. What was frolicking in the meadow one month, may have been a page in a Bible the next. The skin of animals (calves, goats, sheep) was turned into parchment, which was subsequently cut into sheets. Parchment was introduced in late antiquity, when the codex (a book made of double leaves), was born and started to replace the papyrus scroll.

There is a lot you can tell from medieval skin. Like a physician today, the book historian can make a diagnosis by observing it carefully. The quality of parchment sheets varied considerably. Like people today, not all medieval creatures had perfect skin. Some cows loved to rub against trees while others were particularly prone to insect bites. We can still see these defects today, which appear as tiny holes, gaps or dark patches as we read Saint Jerome or Chaucer.

Perfect skin

The quality of the page also had a lot to do with preparation. A scribe producing a book for his own library may be less attentive than one that worked in a monastic community. The best sheets have a deep-white color, with a hint of yellow. They feel like velvet and make a slight rustling sound when you turn the page—suspenseful whispers that teased the reader (image above). Bad skin, by contrast, crackles. It is of uneven thickness, and shows staining and a variety of colors (image below). Unlike what you may have thought, looking at imperfect skin is far more interesting than studying its perfect counterpart. This is because a defect tells a powerful story, shedding light on the book’s production and providing clues about its use and storage post-production.

Damaged goods: holes and rips

Medieval craftsmen were well aware of the varying quality of animal skins, which they used as the basis for their books. However, calves, sheep or goats that had given up their livelihood and skin for the sake of medieval readers were not always to blame—and neither were the scribes. The most common imperfections are holes produced by the knife of the parchment maker.

Preparing parchment was a delicate business. In order to clear the skin of flesh and hair, it was attached to a wooden frame, tight like a drum. If the round knife of the parchment maker (the lunellum) cut too deep during this scraping process, elongated rips or holes would appear. A small puncture easily became a gaping hole. The art of preparing animal skin was to apply just the right amount of pressure.

However, readers did not seem to mind the holes too much and scribes usually just wrote around them, or they repaired them. Sometimes the reader is given an unexpected sneak peek onto the next page—where a dragon may just be introduced into the story (as in the image above).

The jabs of parchment makers—and the resulting holes—were sometimes stitched together. The image above shows a former rip (a long one) snaking across the page: the scribe has stitched it up like a patient in post-op.

Repairing holes was sometimes done more eloquently. In the manuscript above, the hole is not made to disappear, but it is highlighted by colored threads. In some monastic communities this must have been common practice, given that they repaired a lot of books with such “embroidery.” The practice turned defect into art: good-looking bad skin.

Hair follicles

Another skin problem encountered by scribes during a book’s production was the animal’s hair follicle—the skin organ that produces hair (seen above). These follicles show as pronounced black dots on the white page. Often parchment makers or scribes were able to sand them away, producing the desired smooth and cream-colored surface. However, if the follicles had been too deep in a calf or sheep, no dermatologist could have removed the imperfection, let alone the blunt instruments of the scribe. The only thing to do was to write around the patch. The follicles are helpful because they allow us to determine— from the distance between them—whether the animal was a calf, a sheep or a goat. This, in turn, may shed light on where the manuscript was produced: the use of goat, for example, often points to Italy.

The transition to paper

In the 12th century another material appeared in Europe: paper. Imported from Arabic culture, it was first exclusively used for documentary purposes, such as account books and letters. In a remarkable shift of scribal practices, in the fourteenth century scribes all over Europe started to use paper for manuscripts. Conservative scribes, such as monks, ignored the new material for some time, while others—especially those who wanted to economize—embraced it. Paper and parchment were used for all sorts of manuscripts, from chunky volumes to small portable books.

Additional resources:

Making Manuscripts: The Page

by DR. KATHLEEN DOYLE AT THE BRITISH LIBRARY

Video \(\PageIndex{6}\): How did scribes prepare their pages for writing? Patricia Lovett examines the tools for ruling and line marking in medieval books.

Skins and scraps

Leftovers (schedulae)

When the scribe cut sheets out of the animal hide, he would normally use the best part of the skin—what may be called the “prime cut.” This meant staying clear of the very edge of the skin because these areas were very thin and translucent, and deemed unsuitable for books. The scribe therefore cut a rim of parchment from the edge of the skin. It usually came off in tiny bits and pieces, which he called schedulae—strips. These odds and ends were thrown in the bin. Sometimes they were taken out to be used as scraps, for example for taking notes in the classroom or for smaller pages inserted into existing manuscripts (see image above). These tiny pages supplemented the text or added notes, like our yellow sticky notes today.

Layers (palimpsest)

What to do when you run out of parchment as a medieval scribe? You can look around for something else to write on, such as left-over parchment strips in the bin (schedulae), or use paper, if it is available. Alternatively, you can take a book that is no longer used from your monastery’s library and scrape the text off its pages. You then simply apply text of your own. Such recycling resulted in a “palimpsest,” which holds a removed “lower text” and a newer “upper text.” The ink of the reapplied text often does not stick to the page very well, as is clearly seen in the image. Moreover, the older reading often shines through. Especially important are palimpsests from the earlier Middle Ages, because underneath this old text an even older work is buried, like a stowaway. With digital photography the lower text can sometimes be made visible again, which makes studying these books like digging for treasure.

Post-production

Bad skin may also tell us something about the individuals who owned, read and stored manuscripts. The presence of holes and rips may for example indicate the cost of the materials. Studies suggest that parchment was sold in four different grades, which implies that sheets with and without visible deficiencies may have been sold at different rates. If this was indeed the case, an abundance of elongated holes in a manuscript may just point at an attempt to economize on the cost of the writing support. In other words, bad skin may have come at a good price.

Parchment provides other information about readers as well, for example that he or she stored a book in an unsuitable location. Damp places, for one, would leave a mark on the manuscript’s skin, as is clearly seen in a manuscript I sometimes call the “Moldy Psalter”—for moldy it is.

On nearly every page the top corner shows a purple rash from the mold that once attacked the skin. It is currently safe and the mold is gone, but the purple stains show just how dangerously close the book came to destruction—some corners have actually been eaten away. Similarly, if a book was stored without the proper pressure produced by a closed binding, for example because the clasp was missing, the parchment would buckle and produce “waves” on the page.

Apart from such attacks by mother nature, a manuscript could also be scarred for life by the hand of men—those evil users of books. Well known are cases where scribes and readers erased text with a knife, either because the reading was wrong or because they disagreed with it. However, in the wrong hands a knife could easily have a more severe impact on the book’s skin. All those shiny letters on the medieval page were too much for some beholders. The individual that gazed at the golden letters in the manuscript shown below used his knife to remove some of them.

While the velvety softness of perfect skin can be quite appealing to handle, getting to know imperfect parchment is ultimately more interesting and rewarding. Damage is telling, and it may shed light on such things as the attitude of scribes (who did not necessarily mind holes on the page), the manner in which a book was stored by its owner (with a missing clasp or in a wet environment), and even the state of mind of those looking at it (“Must cut out golden letters!”). As a book historian it feels good to work with bad skin.

The work of the scribe

Get set!

Before a single word flowed from his pen, the scribe needed to prepare the page. Whether he had opted for parchment or paper, the sheets were completely blank to start with. So, he first needed to think about a sensible layout, carefully considering his options. Did the text he was about to copy carry certain conventions? Was it, for example, a book that was to contain glosses (notes), or was it made for portable use? Preparing the page was a labor-intensive process, especially when the scribe had opted for a complex layout, with multiple columns and glosses. It was important to get it right since a messy layout would produce a messy book.

Rules

Unlike our notebooks today, medieval paper and parchment sheets did not come with ruled lines when you purchased them. A medieval page consisted of both horizontal and vertical ruling. To add these guiding lines to the blank page, the scribe would prick tiny holes in the outer margins, as well as in the upper and lower ones. Lines were then drawn between these holes, usually with the help of a ruler: horizontal lines to guide the space between each line of text, and vertical lines to confine the left and right side of the textblock.

Until the early twelfth century the ruling was done by pressing down on the parchment with a sharp object (a “hard point”), producing a “gutter” that would guide the scribe’s pen. In the twelfth century this type of ruling was replaced by drawing lines with a pencil (called a “plummet”), which left more visible traces on the surface of the page. From the thirteenth century a pen was used as well. Because of all these horizontal and vertical lines, if a layout was very complex, the ruling pattern may appear as a true cobweb.

Puzzles

How a page was designed depended on a variety of factors, including the number of required text columns, the space left blank for decoration, and the presence of marginal glosses and running titles. The most basic layout consisted of a single column of text. They are frequently encountered in Books of Hours (books made for use in private devotion), because these are commonly smaller books, which facilitated portability. Bigger books of two or more columns often required more work in the design stage, especially if that book also featured a marginal commentary. Particularly challenging were those cases where the commentary was of unequal length. This meant that the scribe had to design each page separately. Piecing together the segments of main text and commentary (see image) was like solving a puzzle.

Location, location, location

As with our modern books, medieval manuscripts consist of quires, small packages of folded leaves. Scribes often produced the quires themselves, but it also appears that they used prefabricated quires bought in a shop. The scribe would copy the text onto the pages of the quire, which would later be bound together to form the completed manuscript. To make sure that each finished quire ended up in the correct order, the scribe often wrote the first words of the next quire in the lower margin of the last page he copied. These are called “catchwords.”

If the catchword at the end of the quire matched the first word on the next quire, then they were in the correct sequence. To help binders put the quires in the right order, scribes would also number them. In the later Middle Ages, further organization was added to the page by also numbering the individual bifolia, so as to keep track of their specific location within the quire. In spite of all this emphasis on location, from time to time binders still jumbled up the sequence.

Bundling sheets

Quires are usually made from bifolia (singular: bifolium) or double-sheets of parchment or paper. To create a bifolium, a sheet is folded in half (each half is called a “folium,” which consists of two pages, i.e. the front and back of the folium). If the quire is the building block of the medieval book, the bifolium is what defines the quire: four, five or six of them were bundled up and subsequently filled with text.

Looking closely at the binding of the book, each bifolium appears to embrace its neighbor, bonding together to produce a strong quire. Before roughly 1200, bifolia were usually cut from processed animal skins, each of which usually supplied usually one to four double-sheets. They were either cut from the skin, or the skin was simply folded, either once (folio), twice (quarto), or three times (octavo). Paper double-sheets were exclusively produced by folding the full sheet.

Irregularities

Quires form the building blocks of the manuscript. How many bifolia the scribe bundled together often depended on his or her location. Book producers in England, for example, are known to have regularly produced quires of six bifolia, while scribes on the continent typically preferred quires of four bifolia. Some quires are irregular. An extra folium could be added (called a singleton) or a leaf could be cut out. Such instances of irregularity are of great interest to book historians, because they may suggest that the original composition was expanded by the scribe (for which an extra folium was needed) or because a blank folium was removed at a later stage, for example because it came in handy for taking notes.

Additional resources:

The making of a medieval manuscript (interactive from the Fitzwilliam Museum)

Words, words, words: medieval handwriting

The hard work of the scribe

“The fingers write, but the whole body suffers,” (medieval saying)

Parchment makers prepared skins, scribes cut their pens and filled their ink pots, and binders packed their workshops with leather and wood. All these activities would be in vain were it not for the single event that sparked them: copying words.

Writing a medieval text with a quill is hard work. The pen could only make a more or less downward movement because of how the nib was cut. It meant that letters had to be broken up into multiple pen strokes. This made writing a very slow process: a Bible could easily take a year to complete. A scribe’s handwriting—script—can tell us where and when he was trained to write. Script tells us these things because the shape of letters was constantly changing—script is thus an important historical tool that helps to place stories and information into their proper cultural-historical setting.

What you can learn from medieval script

Medieval script—the handwriting of the scribe—is the material representation of a text. An author may have composed the text, producing the original thought, poem or story, but it was often the scribe who put these words on the page. Much rides on how he did this. If he was inexperienced, it may be difficult to decipher his writing. If he was sloppy, the wrong words may appear on the page, or the right ones in the wrong order. The handwriting of scribes varied considerably. Not only did individual scribes vary their individual letter forms, as we still do today, but style of medieval script often depended on when and where it was written. This makes script extremely useful for book historians: the producer of a manuscript may tell us, between the lines, where and when he made the book. “My maker is from Germany,” a letter or abbreviation may for example say. From time to time scribes would even say so explicitly, in a colophon at the end of the book.

The main book script of the Middle Ages: Caroline Minuscule

Caroline Minuscule is the primary script of the early Middle Ages. Created in the late eighth century, it became the main book script in the empire of Charlemagne. It is an elegant script with a particularly round and spacious appearance Because Charlemagne had conquered a vast amount of territory during his reign, he found himself with an empire of many cultures, each with its own style of handwriting. A cohesive and unifying script was needed if his administration was to function properly. Caroline Minuscule looks familiar to our modern eyes because producers of typeface working for early Italian printers used it as a model. In fact, the ubiquitous default font “Times Roman” on our computers is also based on Caroline Minuscule.

The transition to Gothic script

From the middle of the eleventh century Caroline Minuscule, the dominant book script at that time, started to include new letter forms. By 1100 the number of letter transformations had grown to such an extent that the script looked different from Caroline. Slowly the script evolved into what may be regarded as the second major book script of the Middle Ages: Gothic (used from c. 1225). Where Caroline was a unifying script, the transitional script of “The Long Twelfth Century” (1075-1225) divided Europe in distinct regions. Scribes in Europe adopted the new, hybrid writing form at different speeds, while they also varied the actual appearance of certain letter forms. Scribes in Germany, for example, were far more conservative than their peers in France and England.

Cursive vs. book script

Books written between 1250 and 1600 were copied in a variety of Gothic scripts, some of which sport very different features. On the one side of the spectrum, there are formal book hands, presenting upright letters that appear to stand at attention. On the other side there are more casual cursive scripts, which were written with a thinner pen and featured connecting loops. By the early fifteenth century these two script forms were equally popular, although cursive script was introduced much later in book production. The introduction of cursive script is part of a broadening palette of scripts. This expansion may have resulted from the commercialization of book production—a consequence of the increasing demands of readers who purchased their books in small urban shops.

Cursive script began its career in the world of administration. Here it was used for account books, charters and other administrative texts. The clerks who produced these documents used a much thinner pen than what was used for formal book script. The flexible tip allowed for a faster pace and it gave the script a kind of “casual” feel.

While book script required the pen to be lifted between each stroke that formed the letter, with cursive script the pen remained on the surface of the page, with each letter connected by a ligature (or loop). Around 1300 this administrative script was exported to the world of book production. Students and scholars were early adopters, as were individuals involved in administrative duties, such as clerks, notaries and merchants. Civic clerks, for example, are known to have produced literary manuscripts after-hours, in part for an urban clientele who paid for their services. These professional users encouraged the migration of the script beyond its initial administrative setting.

Making books for profit in medieval times

While one may be inclined to emphasize how “foreign” the medieval book is—they are, after all, made of dead cows, and are handwritten—they present such recognizably modern features as a justified text, footnotes, running titles and page numbers.

Visiting a bookseller

The similarities run much further than mere physical traits, however. Take for example the manner in which the book was made and acquired from the 13th century onwards. If you wanted a book in the later Middle Ages you went to a store, as in our modern day. However, the bookseller did not normally have any books in stock—except for perhaps some second-hand copies. You would tell him what you wanted, both content-wise and with respect to the object’s material features. You could specify, for example, that he use paper (instead of parchment), cursive script (and not book script) and add miniatures (or forego decoration). Just like so many other objects you bought in late-medieval society, the commercially-made manuscript was custom-tailored to the individual who purchased it.

The professionals who made books for profit were usually found near the biggest church in town. This was a well-chosen spot as canons and clerics (i.e. people who visited the church and who could read) formed an important part of the clientele. By the 14th century true communities of the book had formed in the neighborhoods around churches and cathedrals. Evidence from such cities as Antwerp, Bruges, Brussels, London and Paris suggests that in these communities a diverse group of artisans interacted with clients and with each other. It was a world bound not only by the book, however, but also by profit.

Marketing

Whether you were scribe, illuminator or binder, as a professional you would strive for quality and diversity as this ensured bread and butter on the table. In parallel to our modern book business, medieval manuscript artisans used various marketing strategies to attract new clientele. The most striking of these is advertisements. Scribes hung large sheets outside their doors to show what kind of scripts they had mastered. The short writing samples found on these sheets were often accompanied by the names of the scripts, which shows just how professional the world of the book had become. A particularly rich specimen survives from the shop of Herman Strepel, a professional scribe in Münster (c. 1447). In the true spirit of medieval marketing he wrote the names of all the scripts in golden letters on his advertisement sheet.

Scribes also included advertisements in books they had copied for a client. An example of such “spam” is found in a French manuscript made in Paris by a scribe who calls himself Herneis. On the last page of the book he writes, “If someone else would like such a handsome book, come and look me up in Paris, across the Notre Dame cathedral.” Herneis and his fellow bookmen lived and worked in the Rue Neuve Notre Dame, which served as the center of commercially-made vernacular books. Similarly, students were served in the Rue St Jacques, on the Left Bank, where the latest Latin textbooks were on offer. For Parisians and students it was handy to have all the professionals in one street: you knew where to go when you needed a book and it was easy to check out who was available for making one for you.

Book streets

This centralization was equally convenient, however, for the artisans themselves. Booksellers (also called stationers) in Rue Neuve Notre Dame and in other such “book streets” in European cities depended on the professional scribes, illuminators and binders that lived in their vicinity. They would hire them for various projects. When a client came to order a book from a stationer, the latter would divide the work among the artisans he usually worked with. One copied the text, another drew the images, and a third bound the book. These hired hands were given contracts which specified precisely what they would have to do and how much money they received for it. From time to time the stationer would come and check on the progress they made. In some manuscripts these cost estimates were scribbled in the margin. Although making books for profit was a common scenario in the later Middle Ages, it did not make you particularly rich. On the last page of a Middle Dutch chronicle a clearly frustrated scribe wrote, “For so little money I never want to produce a book ever again!”

The printing press and the demise of the manuscript

The world of professional medieval scribes was shaken up by the coming of Gutenberg’s printing press around the middle of the 15th century. The ink pots dried up and the handwritten book slowly turned into an archaic object that was more costly than its printed counterpart. In the 16th century only large choir books (which did not fit on the press) and handsome presentation copies, custom-made for an affluent client, were still written by hand.

And so we see scribes jumping the handwritten ship, many ending up working in printing shops. Here, too, a striking parallel between the medieval and modern world of the book may be pointed out. Medieval producers and salesmen of books had to adapt to the new medium made popular by Johannes Gutenberg, just as publishers today have to change their ways in a world where pixels are gaining ground over ink.

Decorating the book

Dazzling

Some medieval readers preferred pretty pictures and shiny decoration in their books. Not only did the sparkling page appeal to them, it also proved their economic status, or that the gift they gave was special. Undecorated books were also expensive, but decorated copies cost a true fortune, especially if gold was used. In a process called gilding, the decorator would apply an ultra-thin film of flattened gold to the page, which looked not unlike our modern tin foil.

This page shows that the golden shapes were not appended directly to the surface of the parchment, but that they were stretched over little “hills” of plaster (note how the orange primer is shining through). This way the gold would catch the light from different angles, maximizing its dazzling effect.

Colorful books

When the quires were filled with text, the rubrics (title or chapter heading, often in red) were in place, and the scribe had corrected his work, it was time for the finishing touches. Many medieval books contain some kind of decoration in addition to the written words, usually executed by a different artisan. There is a considerable variation in style and quality of decoration, and, consequently, in cost. At the lower end of the scale is penwork flourishing, red and blue lines drawn with the pen in various patterns and shapes. Some of these typify local styles, allowing us to tie a manuscript to a specific country, city or religious house. At the higher end of the scale is illumination: often sophisticated little paintings that included color and often gold. While decorated books stand out among their other cousins, on the whole they were not very common.

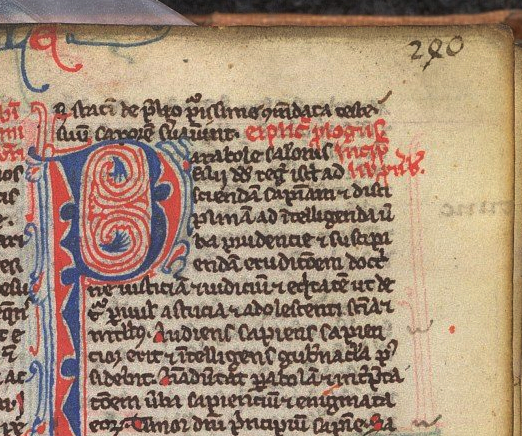

One-letter stories

Normally, letters work together to form words that present a story. From time to time, however, we encounter a letter that contains a narrative all by itself. This giant P initiates the name Paulus (Paul), who was the author of the following Bible text. To mark the beginning of the text the decorator extended the P and applied color and gold to it, turning the letter into a visual aid. Contained in the letter is St Paul himself, presented as the soldier of Christ. In his hand there is a large sword, his standard attribute in medieval decoration, and his head is clearly bald, which also aided in his identification.

While in this case the intensions of the decorator are clear, the meaning of some such historiated initials can only be understood by reading the story they initiate. Miniatures contained even more extensive narratives.

Penwork

In medieval times, penwork flourishing was the quickest and easiest way to add some color to the page. This style of decoration typically involves thin lines, usually in red and blue, drawn with a pen rather than a brush. The swirly lines form lively patterns with unexpected twists and turns, creating miniature mazes in which your eye gets lost easily. If you look carefully you may recognize familiar objects: a tree, the moon, pearls, a smiling face. The central figure attracting all of this artistic attention is the capital letter that needed decorating, in this case the letter “M” (for “Marcus”). The penwork decoration supported an important function of this letter, navigating the reader to the beginning of a new section of text. The specific flourishing patterns can often be pinpointed to a certain city or region, which turns these happy lines into a useful tool for the book historian.

Medieval supermodels

This essay is devoted to a particularly attractive and rare kind of medieval manuscript: the model book. A feast to the eye, the object is filled with drawings and paintings that were meant to show scribes and illuminators how to decorate letters, paint initials, or add large segments of decoration to the page. Within this tradition, two types of model books can roughly be distinguished. Some functioned as instruction manuals. In these books, the drawings might be accompanied by a narrative or explanation that instructs the artisan how to proceed, usually in a step-by-step process. Other model books appear to have merely functioned as a source of inspiration: they present a wide array of shapes and drawings from which the artisan could take his pick.

The level of sophistication among surviving model books varies considerably. On the lower end of the spectrum there are pattern books that merely show how to make enlarged letters with some minor flourishing. On the higher end, by contrast, there are copies with high-quality stand-alone designs and sophisticated historiated initials inhabited by figures and scenes. Evidently the requirements of the artisans varied; and by proxy, so did the taste of medieval readers. It is this variation that makes model books so fascinating, both as physical objects and as cultural artifacts.

Plainly decorated letters

To start at the lower end of the spectrum, some model books merely showed scribes how to execute a certain script or how to draw plain enlarged capitals—the most basic kind of decoration.

The book opening seen above is from Gregorius Bock’s Scribal Pattern Book, which provides instruction on both fronts (more about the manuscript here). Produced in 1510-1517, the first part of the small parchment book contains a series of alphabets in different scripts, some of which are clearly influenced by print typefaces. The second part contains decorative initials arranged in alphabetical order. In the introduction to his manual, Gregorius adds a dedication to his cousin Heinrich Lercher Wyss of Stuttgart, who was scribe to the Duke of Württemberg. The arrangement of the material shows how Heinrich likely used the book: he would thumb through its pages until he had reached either an alphabet or capital letter to his liking.

While Bock’s letters are a pleasure to look at, especially for the book historian, his designs are not exactly rocket science. More complex—but still relatively plain—are the models provided by a much older pattern book in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. This appears to be the oldest surviving pattern book for initials: it dates from c. 1150 and was produced and used in a Tuscan workshop. The choice is much more limited than in the previous example: the Cambridge copy does not provide multiple alphabets, nor does it present a wide range of initials (in fact, only about twenty are present). Interestingly, some manuscripts survive in which we encounter decorated letters that could well be modeled from this or a similar model book (like British Library, Harley MS 7183).

Elaborately decorated letters

On the more upscale end of things is the model book known as the Macclesfield Alphabet Book. It was made and used in fifteenth-century England, apparently for the transmission of ideas to decorators or their assistants.

The artisans were offered quite a lot of choice, given that we encounter no less than fourteen different alphabets on its pages. What makes this book so special, however, is their quality and the manner in which the letters are designed: their shapes are produced by human figures in various uncomfortable positions—doing yoga exercises, it seems.

A similar subject matter is encountered in the alphabet book of the Italian artist Giovannino de Grassi (above). This book was created at the Visconti court in Milan and features both initial letters and stand-alone drawings. The Visconti’s were important patrons of the arts and so it makes sense that we see their generosity extend into the world of book production.

Giovannino was known for depicting exotic animals in their natural habitat and this book features such images as well. His pages provided models for other artists who wished to replicate his realistic depictions (the image of the cheetah to the left is from his workshop).

Marginal decoration

Even more sophisticated are model books that show how to create elaborate decoration that runs in the margin along the length of the page. These border decorations, with their curly leaves and unexpected turns, could be tricky to produce.

The so-called Göttingen Model Book, made around 1450, provides a solution to this problem. Its pages not only show, step by step, how to build a 3D leaf pattern, they also present detailed instructions like the following:

The foliage one shall first draw with a lead or a point. Then one shall outline the foliage with a pen and with very thin ink or with thin black color. Then one shall polish the foliage with a tooth, so that the color can be applied smoothly, but not too firmly. Then one shall paint it with the colors, one side right and the other side left or reversed, with a brush, namely light red and green. […] (source)

The drawings and narrative clearly complement one another. From time to time the instructions mention something like “as it is shown here” or “as the image shows.” A model book can hardly be clearer than this: while the alphabet books shown above were more or less meant to simply inspire the artist, the Göttingen book really takes the artist by the hand and guides him through each step of the production process. The instructions apparently worked well, as is shown by a surviving Gutenburg Bible that contains these very leafy borders (see above right).

The final point

Models are crucial in any learning process. Observing how something is done helps you acquire a skill you lack as much as it encourages you to develop further those you already have. Moreover, there is an additional use to these pattern books that has not yet been mentioned: patrons visiting artisans’ shops could well have been given these objects to find out what the book-maker was capable of providing. Given its many uses, it is hardly surprising that the tradition shown in this blog is also encountered in other cultures, including Byzantine and Arabic book production.

One particularly unusual Arabic specimen deserves to make the final point of this post. The fragment shown above presented Arabic decorators with models of scenes from the New Testament. It figures that the artisans, used to decorating the Qur’an, needed a little inspiration when it came to the Bible. This specimen is also interesting because some of the figures have been outlined by tiny holes, meaning that the sheet could be used as “tracing paper” (click the image to see this closer). While this ultimate instruction method took all potential flaws and creativity out of the modeling process, it allowed decorators with lesser talents to produce something beautiful.

Additional resources:

More information on Gregorius Bock’s Scribal Pattern Book

Macclesfeld Alphabet Book at the British Library

Blog post on the Macclesfeld Alphabet Book from the British Library

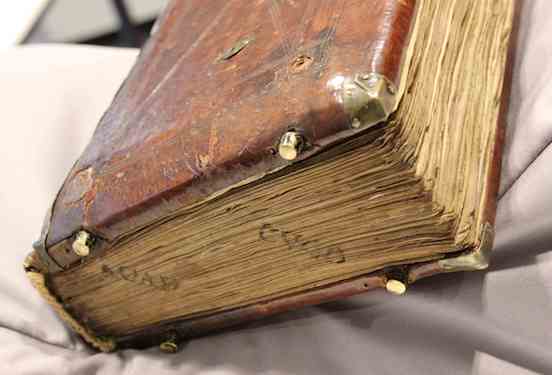

Binding the book

Woodwork

Medieval manuscripts, even small ones, can be surprisingly heavy. Giant Bibles, large volumes that can stand half a meter tall, weigh as much as twenty-five kilos. It requires two library staff members to carry the object to your table. A fair part of this weight is produced by the boards of the bookbinding. To protect the stack of quires that made up the actual manuscript, a wooden board was placed on the front and back. The quires were then tied to thin leather straps, which were pushed through channels drilled through the boards. The straps were pegged into the wood, as seen in the image (note the white straps). It produced a surprisingly firm binding, which lasted for centuries. All this crafty woodwork is presently hidden from our eyes because the boards were subsequently covered with leather (which was often fitted with decoration). Thousands of pieces of medieval trees are presently hidden inside book bindings, like a shelved mini forest.

Wrapper

The so-called “limp binding” is another type of binding that was in popular use in medieval times. Its most notable feature is the absence of boards, which explains its name. With a limp binding the quires are covered by a plain parchment wrapper without the support of wooden boards.The quires in these bindings—usually a limited number—are attached to the outer parchment with thin strings, which are visible on the outside. A limp binding resulted in a lighter manuscript, which meant it was easier to transport. This type of binding also decreased the cost, given that wood was not needed and that the binding process was less time-consuming. This is likely why this type of bookbinding was so popular among medieval students.

Accessories

Many medieval books were a joy to look at even when they were closed. Various shiny “accessories” were drilled in and attached to the wooden boards on the outside of the book. The most pronounced of these are the so-called “bosses,” protective metal pieces attached to each corner of the binding. Much more common are clasps, pieces of metal that kept the book closed. These were needed because, unlike paper, parchment has a tendency to expand and buckle, which could push the book open. A clasp was therefore needed to keep the book closed when not in use, protecting the text inside. Also frequently added to the binding is decoration—flower motifs, playful line patterns, and at times even a painted scene. Such decorative elements on the outside of the binding became particularly common near the end of the Middle Ages.

Clasps: hugging a medieval book

Book historians tend to compare features of the medieval book to body parts. Thus the manuscript’s “head” (top edge) is connected to its “spine” (the back) via the “shoulder” (the area where board meets spine). There are even terms that compare a medieval book’s physical features to human activities or conditions. A large letter with a lively figure inside is called a “gymnastic initial,” for example, while line ruling that is nearly invisible is “blind.” This article takes this projection phenomenon a step further. It shows how one particular feature of the medieval binding eerily resembles a body part, not just in appearance but even in function: the clasp.

Arm and hand

While a medieval book was produced to be opened and used, medieval makers of manuscripts paid just as much attention to closing it. In order to preserve the organic pages, which were often made of parchment, it was necessary to keep the volume tightly closed when it was not used. Not only did this keep moisture out, but parchment also has a natural tendency to buckle, especially when handled at room temperature. In fact, parchment pages curl up with so much force that the wooden boards would be pushed open were it not for a smart device designed to keep the lid on: the clasp.

The clasp is like an arm that extends from the one wooden board to the other. Indeed, it is hard not to think of clasps as hugging arms that embrace the leaves, safeguarding them from the harsh reality of medieval book use. Appropriately, the primary purpose of clasps was to protect the pages. They generated the pressure needed to keep the pages flat, while producing a firm object that could withstand every-day use in a medieval library—like falling off a desk or a shelf. At the end of the arm a tiny “hand” locks into an extension, as clearly visible in the image above. How great that some book binders played with the image of a hand grabbing onto the opposite clasp, as this eighteenth century example shows (above).

Generally, two clasps were able to contain the force issued by the buckling parchment of a book. However, it was important to get it right as a bookbinder. When the distance between the one end of the arm (the “arm pit”) and the handle bar was too large, there was insufficient pressure. By contrast, if the distance was too little, the book did not close. Medieval manuscripts that have lost their clasps (by far the majority) show what happens to the bookblock when the pressure was too low: unhappy pages with a wavy pattern appeared (above).

Exotic arms

Some readers preferred exotic clasps. A particularly remarkable specimen is in the National Library of Sweden. The book it helps to close is tiny, no larger than an iPhone. Made c. 1500, it was designed for the road: it concerns a portable Book of Hours (or prayer book) that was carried around by a pilgrim on his religious pilgrimage. The clasp holding it closed is in fact a skull carved out of bone. The theme is fitting for a pilgrim seeking redemption, finding his way along the dusty roads of medieval Europe. Every time he sat down to open his book he was confronted with his future, which looked rather grim: Memento mori, remember that you will die one day. Better smarten up and keep on going!

The exoticness of clasps is sometimes connected to their number instead of their shape. Clasps are a must for a peculiar binding known as dos-à-dos (or “back-to-back”). While such bindings usually hold two books bound together at their backs (hence the name), the National Library of Sweden owns a unique variant that contains no less than six books. They are all devotional texts printed in Germany during the 1550s and 1570s (including Martin Luther, Der kleine Catechismus) and each one is closed with its own tiny clasp (see the various openings here). A book with six arms and hands: it is quite the display of craftsmanship.