15.1: Ilkhanid

- Page ID

- 108687

Making and Mutilating Manuscripts of the Shahnama

by Dr. Sheila Blair

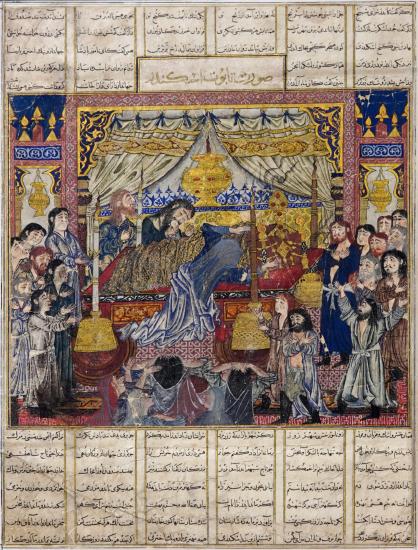

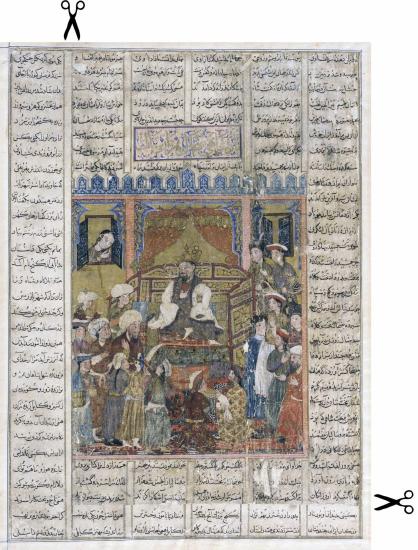

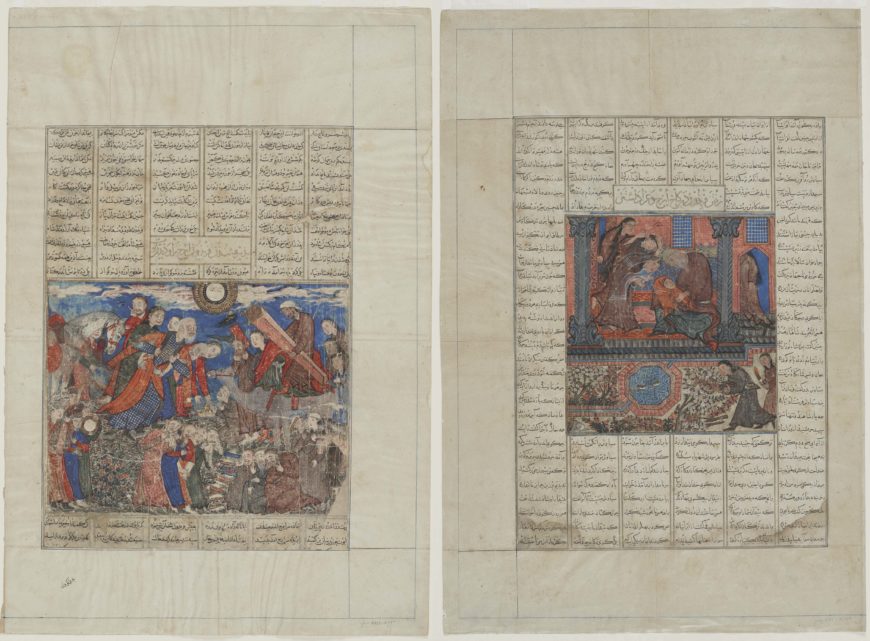

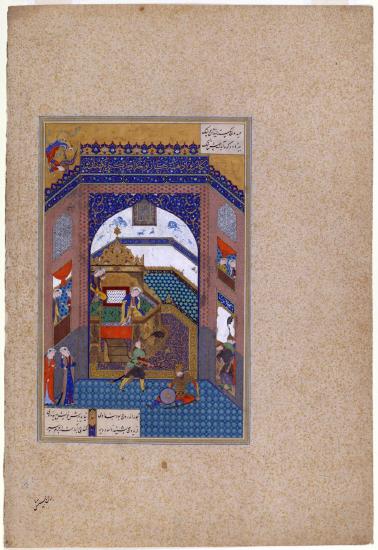

Illustrated manuscripts are one of the glories of Persian art, especially those made during the heyday of production from the fourteenth century to the sixteenth century. The most popular text was the Shahnama, or Book of Kings. This 50,000-couplet poem recounts the history of Iran from the creation of the world to the coming of the Arabs in the seventh century through the reigns of fifty successive monarchs. Rulers and their courtiers often commissioned splendid copies of the Shahnama to link themselves to the heroes of the past, whether the “Alexander of the Age” (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)) or “The Lord of the World" (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) and detail, Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

Today some of the most important manuscripts are sadly dismembered. Reconstructing the history of two of these splendid manuscripts—from creation to mutilation—shows how they have been used (and misused) over the centuries as political propaganda, loot, and even fodder in the international art market.

The Great Mongol Shahnama and the Tahmasp Shahnama

These two illustrated pages (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) and Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) come from the most ambitious manuscripts known: the Great Mongol Shahnama, made for the Mongol court in northwest Iran around 1330, and the Tahmasp Shahnama, made two centuries later in the same region for the Safavid shah Tahmasp (and perhaps inspired by the earlier one).

Large books with hundreds of illustrations

Both of these manuscripts are very large books. The 759 folios, or leaves, in the Tahmasp Shahnama measure 32 x 47 cm (12½ x 18 ½ inches) with a whopping 258 illustrations, many of them nearly full size and sometimes spilling into the gold-sprinkled margins. The Great Mongol Shahnama was even larger: it had around 300 folios with some 200 illustrations, most about half or two-thirds the area of the written surface. [1] Both projects must have taken a decade to complete, even with a workshop of papermakers, calligraphers, painters, illuminators, binders, and other craftsmen.

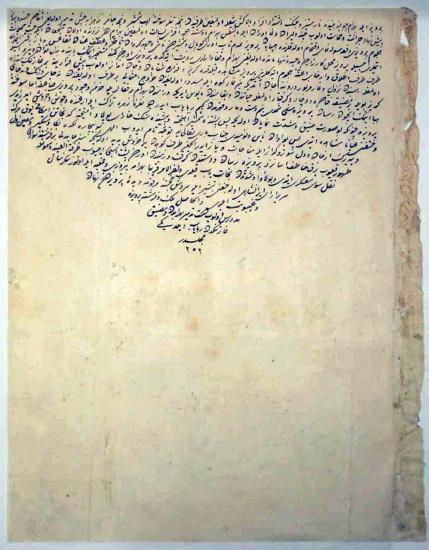

Both manuscripts became part of the royal library, a necessary accoutrement of a cultured prince from the fourteenth century onwards in Persia and elsewhere. The Great Mongol Shahnama seems to have stayed there until the nineteenth century when the manuscript, perhaps unfinished or damaged, was repaired: some of the faces in the paintings were retouched with pink cheeks and heavy eyebrows typical of the nineteenth-century Qajar style, the folios were numbered and remargined on imported Russian paper dated 1832, and the original two volumes were conflated into one. A photograph taken in Tehran at the end of the nineteenth century by the Armenian photographer Antoine Sevruguin shows the bound volume open to one of the illustrated pages (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

The Tahmasp Shahnama is given to an Ottoman sultan

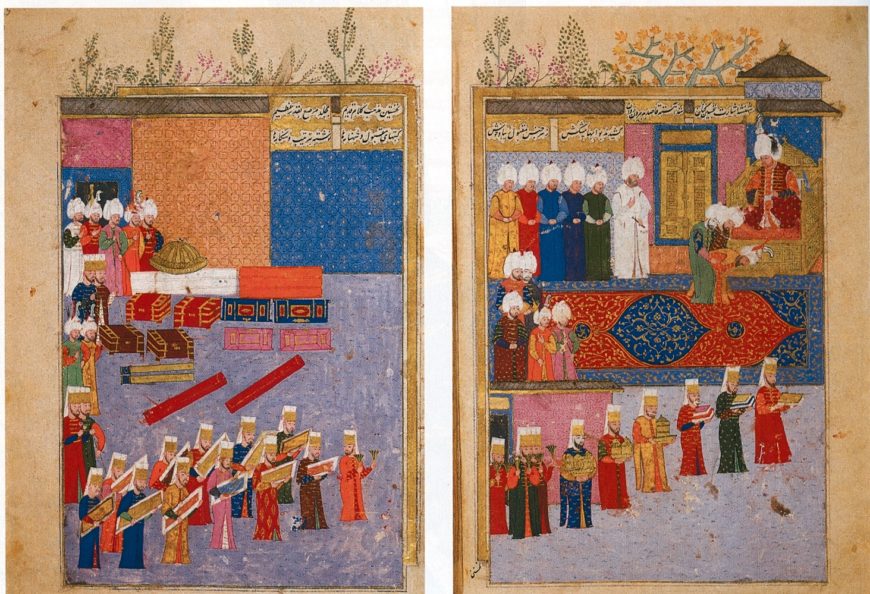

The Tahmasp Shahnama had a different trajectory. It remained prized at Tahmasp’s court for a few years, as the court librarian Dust Muhammad extolled its painting of “The Court of Kayumars” in an album preface written in 1544, and two illustrated folios were replaced for unknown reasons. But then in 1566 Tahmasp, who had apparently tired of painting and dispersed his royal workshop, decided to give the manuscript to the Ottoman sultan Selim II to mark his succession. Tahmasp sent the Shahnama at the head of a long camel train along with a Qurʾan manuscript attributed to the hand of Prophet’s son-in-law ʿAli ibn Abi Talib, books chosen to emphasize the shah’s royal and religious pedigree and show up his rival as a mere parvenu.

The Ottomans got the message, and their reception of the embassy and its gifts was just as orchestrated. They produced their own richly illustrated dynastic histories, including one with a painting showing the enthroned Selim loftily accepting the gifts from groveling ambassadors as a form of entitled tribute rather than an exchange between equals (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)).

The Ottomans sequestered the Tahmasp Shahnama in their royal library. It may have been examined occasionally, as details of the Safavid paintings are occasionally repeated in Ottoman manuscripts, but the lack of fingerprints, smudges, creases, and other marks show that few people consulted the volume. One exception was Mehmed ʿArif Efendi, keeper of guns at the court treasury, who added synoptic commentaries about the paintings in Ottoman Turkish in 1800–01. Written on polished sheets that were glued into the manuscript opposite the illustrated pages (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\), these synopses suggest that readers at the Ottoman court, which by this point used Ottoman Turkish, merely flipped through the Persian text, looking only at the paintings.

Cutting up the Great Mongol Shahnama

The situation for these and many other illustrated manuscripts changed dramatically at the turn of the twentieth century with political upheavals in the Islamic lands and the growing power of Europe and the art market there. Impoverished courtiers apparently filched manuscripts from royal libraries and sold them to European and American dealers and collectors who had developed a taste for richly illustrated texts. The Tahmasp Shahnama was the first of the two manuscripts to go. By 1903 it had moved, perhaps via Iran, to Paris where it entered the collection of Baron Edmund de Rothschild.

The Great Mongol Shahnama left a few years later, and by 1910 it was in the hands of the Belgian collector Georges Demotte. Unable to sell the whole manuscript, perhaps because of the looming threat of war in Europe, Demotte decided to cut it up and hawk the folios separately to collectors who could display them framed, hanging on the wall. Demotte was faced with a problem, however, as some folios had paintings on both sides.

To maximize his profits, he had the two sides of the folio pulled apart and then remounted the pages separately (such as “Zahhak enthroned” and “Faridun mourning his son”) or had the detached paintings pasted onto other folios (such as “Faridun goes to Iraj’s palace and mourns”) (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)).

In doing so, he damaged some of the pages. Many of them are abraded because of the paper sheets that were temporarily glued on to help separate the two sides of the folio. In a few cases, parts of the folio, including the painted area, were damaged. Some entire pages or folios may have been destroyed. All together, Demotte is known to have sold 58 illustrated folios and a handful of text folios that were attached to them so that collectors could frame a double-page spread to resemble an open book. The rest of this magnificent manuscript, with some of the most emotional scenes ever produced in Persian painting, is missing, likely destroyed.

The dispersal of the Tahmasp Shahnama

The Tahmasp Shahnama again followed a different course. Two years after the death of Baron Rothschild’s son Maurice in 1957, the manuscript, intact with all of its 258 paintings, was sold to the American magnate and bibliophile Arthur A. Houghton, Jr. who commissioned the American scholars Martin Dickson and Stuart Cary Welch to prepare a lavish monograph that reproduced all 258 illustrated pages at full size. To make the plates for publication, the volume had to be unbound, a step that presaged its dispersal.

Small groups of paintings, now framed in silk mats, were exhibited starting in 1962 at the bibliophilic Grolier Club in New York, of which Houghton was president. At this time the international art market was heating up, and works of Middle Eastern, particularly Persian, art were in high demand. Empress Farah of Iran was a major collector, and texts like the Shahnama that reflect the glories of Iranian kingship were particularly popular in this imperial era. Houghton, who was in the midst of divorcing his third wife and marrying his fourth, began to auction off his rare books. In 1970 when The Metropolitan Museum of Art celebrated its centennial, Houghton, then chairman of the board, donated 76 illustrated folios from the Tahmasp Shahnama to it (see Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). He needed to establish a tax basis for his donation, and beginning in 1976, individual folios appeared for sale on the market. The first seven comprised works by all the major painters that Dickson and Welch assigned to the manuscript, thereby establishing a unit price for works by different hands.

More sales followed, some to connoisseurs like Prince Saddrudin Aga Khan who acquired what is regarded as the finest painting in the manuscript, “The Court of Kayumars” (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)), but others (such as “Faridun strikes down Zahhak,” Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\)) went to investors such as the British Rail Pension Fund.

The manuscript’s peregrinations did not end there. Following the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the art market changed and uproar over the manuscript’s crass dismemberment increased. After Houghton’s death in 1990, his son decided to sell intact the carcass of the manuscript, including its binding and 118 remaining paintings. Complex negotiations through the London dealer Oliver Hoare led to an arrangement in 1994 with the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tehran to trade the manuscript’s remains for a 1953 Willem de Kooning painting, Woman III, a large oil of a standing nude purchased by Empress Farah but considered distasteful in the Islamic Republic. In a scene worthy of a Graham Greene thriller, the trade-off took place one rainy night on the tarmac of Vienna airport. The manuscript, disbound and deprived of its finest paintings, returned to its homeland where it was feted as a national treasure.

Reconstructing the manuscripts today

It is impossible to undo the damage suffered in dismembering these manuscripts, but scholars have pursued several strategies to help us appreciate some of their original glories. Each approach brings different benefits, but also entails certain limitations. Exhibitions of disbursed folios allows viewers to compare folios side by side, especially important in the case of the Great Mongol Shahnama in which the individual paintings differ so widely. But some museums are prohibited from lending, and few would risk sending all of their folios from one manuscript at a single go.

Another approach is to produce a handsome monograph with full-size color illustrations of all the folios, as Sheila Canby did with the Tahmasp Shahnama to celebrate the poem’s millennium in 2010. The book showcases the wonders of the images, but privileges paintings over poetry and downplays the manuscript as the integral work of art. Calligraphers, heirs to two centuries of tradition in transcribing this text, wanted to have the lines describing the action frame the painting. To do so, they manipulated the layout.

In the case of the “The Angel Surush rescues Khusraw Parviz,” for example, the calligrapher wrote some of the lines on the front side of the folio diagonally so that the page contains only 12 lines of text instead of the standard 22 (Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\), and the couplets describing the angel’s descent fall next to the painting on the reverse (Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). The diagonal layout signals to readers that an illustration is approaching and heightens their anticipation in turning the page.

A digital reconstruction of the manuscript would allow the reader to sense the rhythm while flipping the pages, but such an enterprise is exceedingly difficult given that this manuscript is divided between two major institutions in the U.S. and Iran, with additional folios scattered among dozens of public institutions and private collectors, with some still changing ownership. Furthermore, books in the Islamic lands were never meant to be seen flat, as the bindings allow them to be opened only 110 degrees. Instead, books were read three-quarters open while supported on a cradle or stand. So images of a two-page spread flat on a computer screen directly in front of viewers are distorted and do not convey the original aspect of reading the book. Nevertheless, all of these approaches help us to visually reconstruct these glorious illustrated books, in the words of the Safavid chronicler Dust Muhammad, the likes of which the celestial spheres have never seen.

Notes:

- For the Great Mongol Shahnama, we cannot say exactly how large the folios were since it was remargined, but the written area is more than twice that of the Tahmasp Shahnama (1160 vs 486 sq. cm.) The larger area of writing in the Great Mongol Shahnama allowed for more columns (six vs. four) and more lines (31 vs. 22) per page.

Medieval illuminated manuscripts are portable objects of luxury. Skilled artists not only copied text to the pages, but also imbued them with intricate imagery, rich colors, and gold leaf. Dr. Bryan Keene and Rheagan Martin describe how books such as these were made to be held, carried, and touched (something that, as Sheila Blair noted, evidently did not happen with the Tahmasp Shanama, given its lack of fingerprints). Keene and Martin examine the unique history of illuminated manuscripts as leading “eventful lives” because of the relationship a manuscript had with its owner. More specifically, they introduce how pages of manuscripts featuring religious imagery, such as that of Christ on the crucifix, even acted as “vehicles” with which to connect the reader with the divine. Such images were touched, kissed, and rubbed repeatedly as signs of religious devotion or in acts of prayer. Some images were even touched or rubbed so much that the images became erased over time. In Islamic manuscripts, pious users sometimes sought to render human figures lifeless by rubbing out their eyes, or drawing a line across their necks, symbolically slitting their throats. Other images, such as some showcasing naked figures or people engaged in extramarital sexual activity, even seemed to be rubbed out in an act of censorship. Read Coming Out: Queer Erasure and Censorship from the Middle Ages to Modernity to learn more about how readers and viewers engaged with their manuscripts and how that helps historians now to reveal historical evidence of sexual norms and practices, while and making LGBTQIA history more visible.

Bahram Gur Fights the Karg (Horned Wolf)

by Jayne Yantz

As Bahram Gur’s men faced the Karg, a monstrous horned wolf that had been terrorizing the countryside, they cried, “Your majesty, this is beyond any man’s courage…tell Shangal this can’t be done….”

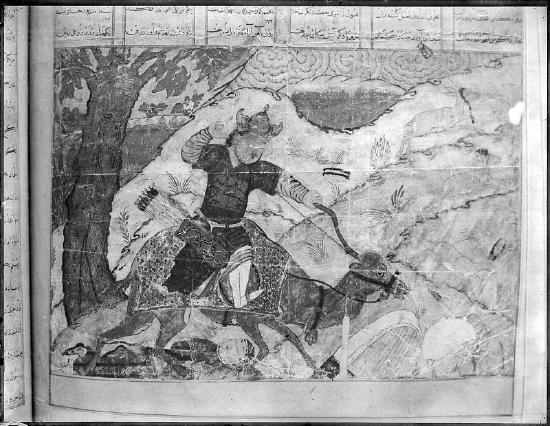

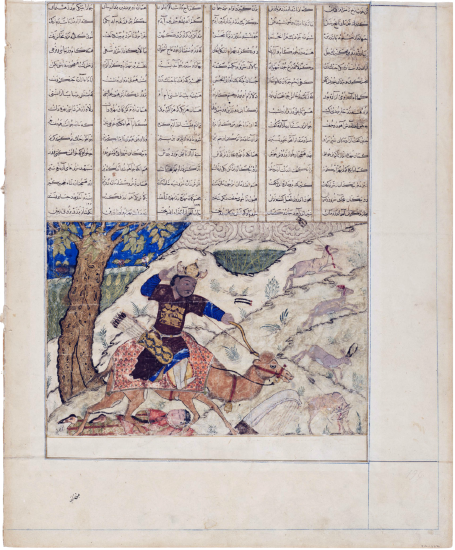

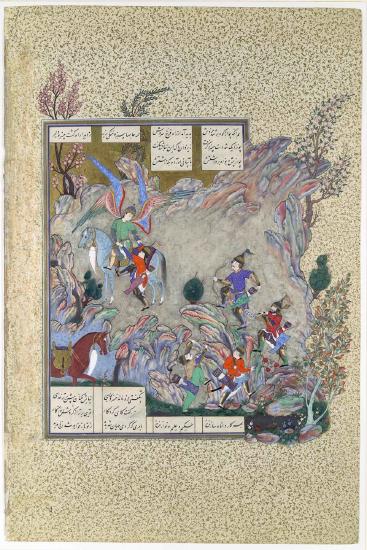

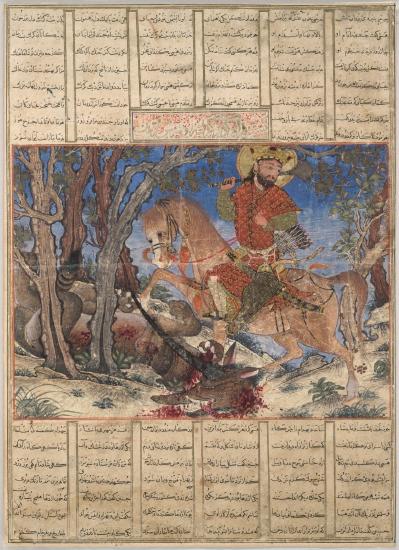

Bahram Gur Fights the Karg is a book illumination depicting one of the many stories from the Shahnama, the Persian Book of Kings. Though this particular image (Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\)) was painted in the fourteenth century by artists in the Mongol court in Persia (present-day Iran), the text of the Shahnama was composed by a poet named Firdawsi four hundred years earlier, around 1000 C.E. The Shahnama incorporates many older stories once told orally, chronicling the history of Persia before the arrival of Islam and celebrating the glories of the Persian past and its ancient heroes. The Shahnama is, in fact, still taught in Iranian schools today, and is considered to be Iran’s national epic—to know or recite the stories of the Shahnama is to express pride in the country’s glorious past. The illustration Bahram Gur Fights the Karg depicts one such story of the brave deeds of a Persian king, Bahram Gur, who single-handedly defeated the monstrous Karg (horned wolf). It is much more than just an exciting tale, however; the Mongol artists who created this work were fulfilling their patrons’ strong desire to identify with the noble, virtuous, and powerful warrior-kings of ancient Persia.

Who was Bahram Gur and what is a Karg?

Bahram V was a king of the Sasanian empire that ruled Persia from the third to the seventh century, just prior to the arrival of Islam. His nickname, Bahram Gur, refers to a “gur” or onager—a type of wild ass which is one of the world’s fastest-running mammals. The word “gur” may also mean “swift.” He was known as a great hunter of onagers (Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)), a favorite game animal in ancient Iran, and he was renowned for his talents in warfare, chivalry, and romance. On a trip to India, according to the Shahnama, the king of India, a ruler named Shangal, recognized Bahram Gur’s abilities and sought his help in ridding the Indian countryside of the frightening and fierce Karg.

Some translations of Firdawsi’s work describe the Karg as a rhinoceros, some as a wolf, and some, as we find here in Bahram Gur Fights the Karg, as a combination of the two—a ferocious horned wolf. When Bahram Gur and his men found the lair and saw the beast, his men beseeched, “Your majesty, this is beyond any man’s courage…tell Shangal this can’t be done….” The hero, of course, went forward alone, first using his bow to weaken the Karg with arrows, then using his blade to cut off the Karg’s head to present to Shangal.

The Mongol court and the art of the book

The Sasanian empire fell in the seventh century, and it was not until well after this that the Mongols invaded Persia. They came from the eastern Asian plains, where open grasslands had encouraged a nomadic lifestyle of herding, horsemanship, and fierce warfare. They first became a serious force under the leadership of Genghis Khan in the early thirteenth century, and later, under his grandson Hulagu, the Mongols expanded their reach all the way to the Mediterranean.

Settled in Persia, the Mongols fostered the growth of cosmopolitan cities with rich courts and wealthy patrons who encouraged the arts to flourish. The rule of Hulagu’s dynasty, which lasted until 1335, is commonly known as the Ilkhanid period. Book illustration thrived under the Ilkhanids and became a major art form for both religious and secular texts. Since the Mongols began as, and largely remained, nomadic peoples (moving from place to place during the year to satisfy the needs of their herds), artworks tended to be small and portable. Their long nomadic history also meant that the Mongols developed strong oral traditions of storytelling, which gave them an appreciation for narrative art—especially manuscripts with paintings to accompany the stories. Illustrated manuscripts were also prestige items, created in very sumptuous formats suitable for kings, princes, and members of the court.

It was within this environment of lavish artistic book production that the manuscript depicting Bahram Gur Fights the Karg was created, probably in a court workshop. The artists who crafted it used silver and gold accents over ink and opaque watercolor. While we do not know the name of the patron, scholars suggest that it may have been the court vizier, a high-ranking official. The full page, or folio, is relatively large for a hand painted book, and because of its size, the manuscript is also referred to as the Great Mongol Shahnama. It was most likely a prestige item intended to express the owner’s power and wealth, and it is the most luxurious of all the Ilkhanid painted books that survive. In its original form, scholars believe this complete manuscript probably comprised about 280 folios (pages) with 190 illustrations painted by several different artists, bound into two separate volumes. Today, however, only 57 folios are known to have survived. Like many other manuscripts, the Great Mongol Shahnama was taken apart by an early twentieth-century art dealer so that the pages could be sold separately.

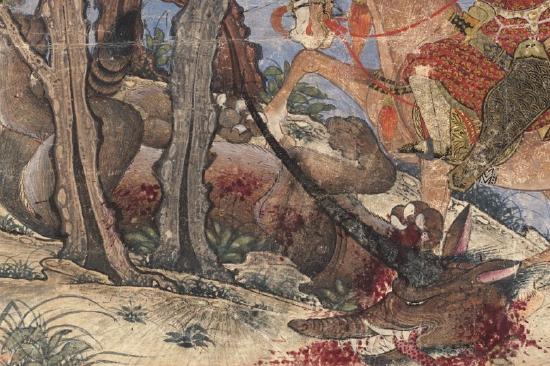

The illumination as a stylistic blend

This manuscript was likely completed at the Mongol court in Tabriz, a rich and cosmopolitan urban center (in what is today northern Iran). By the time the book was produced, the Mongols had settled into their role as refined rulers with international contacts, and their lands were secure enough to ensure the safe exchange of both goods and ideas throughout the empire. The increased availability of paper, invented in China in the eighth century, also encouraged the diffusion of artistic ideas. Consequently, Ilkhanid art had an international flavor. Landscape elements, for instance, often show influences from China, incorporating motifs seen on imported Chinese scrolls (Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\)) and ceramics. In Bahram Gur Fights the Karg, the worn and twisted trees, overlapping forms that create spatial recession, rapidly brushed foreground vegetation, and a taste for asymmetry all suggest eastern Asian influences.

Local influences are also apparent: Persia had a long artistic tradition of depicting heroes, kings, and hunters riding horses over slain opponents. Bahram Gur is depicted in this tradition. Shown on horseback, he wears kingly garb, with a golden crown, luxurious garment, and an elegant gold and pearl earring visible in his right ear. But he is also clearly a warrior, holding a mace over his shoulder, and with a bow, sword, and arrows covered in a leopard skin hanging from his waist.

The result is a dynamic, energy-filled image (Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\)) with a monumental figure almost bursting out of the frame: Bahram Gur is cut off slightly at the top, trees and landscape details are truncated at the edges, and the horse is captured in mid-motion with one leg raised above the Karg. The Karg’s head, very close to the viewer, is centrally placed and dripping blood, while the splayed length of the Karg’s battered body pulls the viewer’s eye toward the left. The focus returns to the hero, however, because a visual circuit is created around him. Our eyes travel along the horn of the Karg, to the continuous arc of the tree branch, and up to Bahram Gur, whose glance leads our eyes back down across the vegetation and the body of his horse.

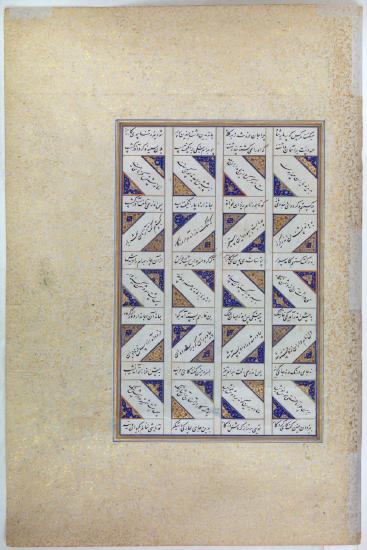

The page surrounding Bahram Gur Fights the Karg is covered with calligraphy (Figure \(\PageIndex{22}\)), but we do not know what originally appeared on the page adjoining the painting because the book pages are dispersed today. Calligraphy is the most highly regarded form of Islamic art, and it can be highly stylized, showing off an artist’s personal flare and skill. Ideals of beauty in Islamic culture draw on calligraphy’s inherent harmony and balance, spacing, proportion and compositional evenness on the page, and these aesthetic values are also visible in the painting style of the Great Mongol Shahnama.

Old heroes for a new regime

There is a tradition within Islam that strongly discourages the visual representation of human or animal figures. In practice, however, figurative representations can very often be found in secular and private Islamic contexts, such as the Ilkhanid court, where it was acceptable—even desirable—to create splendid figurative artworks for private consumption.

This was true of the Shahnama, which was a favorite subject at the Mongol court, eagerly enjoyed by wealthy and sophisticated courtiers. The painters who illustrated the Shahnama were drawn to dramatic subjects such as battles or encounters with astonishing beasts such as the Karg. However, images like Bahram Gur Fights the Karg were not just meant as illustrations of simple, enjoyable fairy tales, but contained deeper meaning and significance for the Mongol nobility. Here, Bahram Gur symbolizes just rule and civilized society triumphing over chaos and disorder, represented by the Karg. In simple terms, this means good defeating evil, but it also implies that a good and stable social order is based upon kingship, and that warrior-kings like Bahram Gur are moral and courageous models to be emulated by the readers of the book. The Shahnama therefore also provided a teaching tool, subtly incorporating moral stories and illustrating desirable behaviors for future kings and nobles.

Many scholars also believe that the new Mongol rulers in Persia wanted to link themselves to the great heroes and kings of Persia’s past, a link which would enhance their authority. The Mongols and the ancient Persians had a shared respect for the manly arts of fighting, hunting, feasting, and courtship, and it is not a coincidence that Bahram Gur rides a horse as he defeats the Karg: the story is Persian, but the hero is shown as a great Mongol horseman.

The Shahnama is filled with magical tales of courtly life, including kings and heroes who fight, hunt, and live life to the fullest, as illustrated in the story of Bahram Gur Fights the Karg. But the Shahnama is also somewhat fatalistic, presenting a hostile world filled with fierce foes like the Karg. The book even ends with the defeat of the Persians by the Arabs. The stories, however, teach about the importance of courage and ethics while traveling through such a threatening world, and they provide guidance for readers confronting questions about death, love, honor and just rule.

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Sheila Blair, "Making and Mutilating Manuscripts of the Shahnama," in Smarthistory, July 27, 2020 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Bryan C. Keene and Rheagan Martin, "Coming Out: Queer Erasure and Censorship from the Middle Ages to Modernity," in Smarthistory, July 30, 2020 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Jayne Yantz, "Bahram Gur Fights the Karg (Horned Wolf)," in Smarthistory, January 20, 2017 (CC BY-NC-SA)