14.1: Medieval Islam Before the Mongols

- Page ID

- 108735

Arts of the Islamic world: The medieval period

by Glenna Barlow

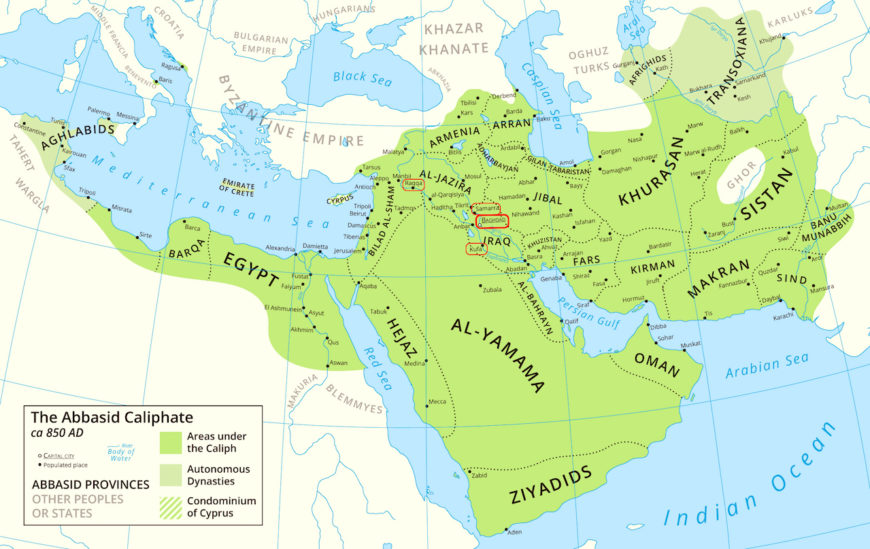

For many, the Muslim world in the medieval period (900-1300) means the crusades. While this era was marked, in part, by military struggle, it is also overwhelmingly a period of peaceable exchanges of goods and ideas between West and East. Both the Christian and Islamic civilizations underwent great transformations and internal struggles during these years. In the Islamic world, dynasties fractured and began to develop distinctive styles of art. For the first time, disparate Islamic states existed at the same time. And although the Abbasid caliphate did not fully dissolve until 1258, other dynasties began to form, even before its end.

Fatimid (909-1171)

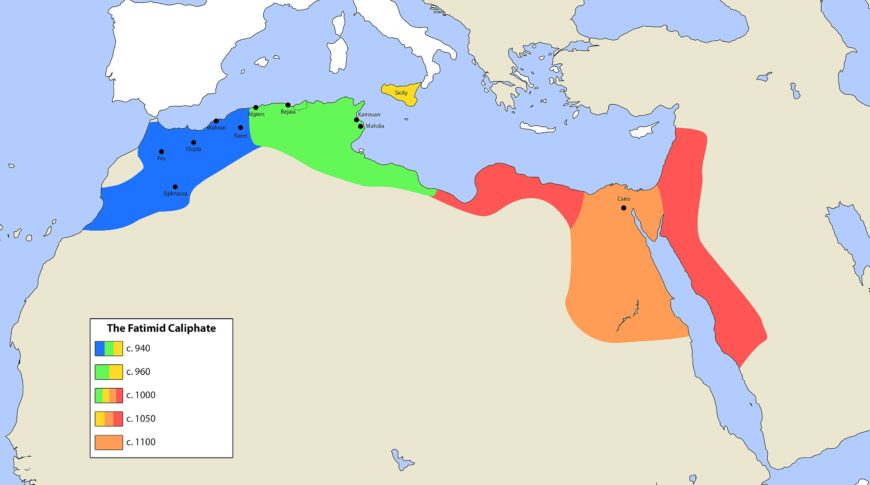

In the tenth century, the Fatimid dynasty emerged and posed a threat to the rule of the Abbasids. The Fatimid rulers, part of the Shi’ia faction, took their name from Fatima, Muhammad’s daughter, from whom they claimed to be descended. The Sunnis, on the other hand, had previously pledged their alliance to Mu’awiya, the founder of the Umayyad dynasty. At the height of their power, the Fatimids claimed lands from present-day Algeria to Syria. They conquered Egypt in 969 and founded the city of Cairo as their capital.

The Fatimid rulers expanded the power of the caliph and emphasized the importance of palace architecture. Mosques too were commissioned by royalty and every aspect of their decoration was of the highest caliber, from expertly-carved wooden minbars (where the spiritual leader guides prayers inside the mosque) to handcrafted metal lamps.

The wealth of the Fatimid court led to a general bourgeoning of the craft trade even outside of the religious context. Centers near Cairo became well known for ceramics, glass, metal, wood, and especially for lucrative textile production. The style of ornament developed as well, and artisans began to experiment with different forms of abstracted vegetal ornament and human figures.

This period is often called the Islamic renaissance, for its booming trade in decorative objects as well as the high quality of its artwork.

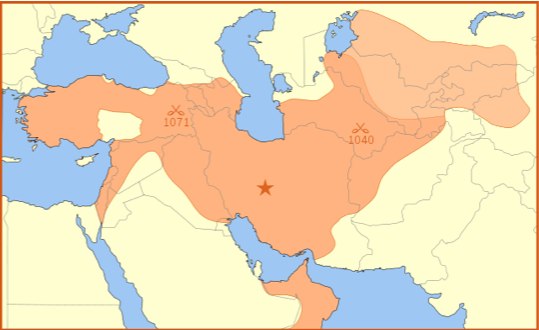

Saljuq (1040-1157/1081-1307)

The Saljuq rulers were of Central Asian Turkic origin. Once they assumed power after 1040, the Seljuqs introduced Islam to places it had not been heretofore. The Seljuqs of Rum (referring to Rome) ruled much of Anatolia, what is now Turkey (between 1040 and 1157), while the Seljuqs of present-day Iran controlled the rest of the empire (from 1081 to 1307).

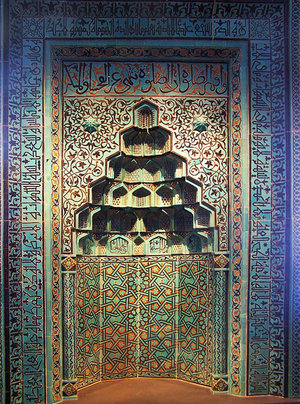

The Saljuqs of Iran were great supporters of education and the arts and they founded a number of important madrasas (schools) during their brief reign. The congregational mosques they erected began using a four-iwan plan: these incorporate four immense doorways (iwans) in the center of each wall of a courtyard.

The art of the Anatolian Saljuqs looks quite different, perhaps explaining why it is often labeled as a distinct sultanate. The inhabitants of this newly conquered land in Anatolia included members of various religions (largely Buddhists and Shamen), other heritages, and the Byzantine and Armenian Christian traditions. Saljuq projects often drew from these existing indigenous traditions—just as had been the case with the earliest Islamic buildings. Building materials included stone, brick, and wood, and there existed a widespread representation of animals and figures (some human) that had all but disappeared from architecture elsewhere in Islamic-ruled lands. The craftsmen here made great strides in the area of woodcarving, combining the elaborate scrolling and geometric forms typical of the Arabic aesthetic with wood, a medium indigenous to Turkey—and rarer in the desert climate of the Middle East.

Mamluk (1250-1517)

The name ‘Mamluk’, like many names, was given by later historians. The word itself means ‘owned’ in Arabic. It refers to the Turkic slaves who served as soldiers for the Ayyubid sultanate before revolting and rising to power. The Mamluks ruled over key lands in the Middle East, including Mecca and Medina. Their capital at Cairo became the artistic and economic center of the Islamic world at this time.

The period saw a great production of art and architecture, particularly those commissioned by the reigning sultans. Patronizing the arts and creating monumental structures was a way for leaders to display their wealth and make their power visible within the landscape of the city. The Mamluks constructed countless mosques, madrasas and mausolea that were lavishly furnished and decorated. Mamluk decorative objects, particularly glasswork, became renowned throughout the Mediterranean (see this mosque lamp in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\), for instance). The empire benefited from the trade of these goods economically and culturally, as Mamluk craftsmen began to incorporate elements gleaned from contact with other groups. The growing prevalence of trade with China and exposure to Chinese goods, for instance, led to the Mamluk production of blue and white ceramics, an imitation of porcelain typical of the Far East.

The Mamluk sultanate was generally prosperous, in part supported by pilgrims to Mecca and Medina as well as a flourishing textile market, but in 1517 the Mamluk sultanate was overtaken and absorbed into the growing Ottoman empire.

Arts of the Abbasid Caliphate

by Dr. Beatrice Leal

The Abbasid period started with a revolution. Caliphs of the earlier Umayyad dynasty had ruled for almost a hundred years after they assumed power in 661 (after the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 CE), and over this time discontent gradually built up against them, both from rival elites and from large sections of the general population. After three years of open fighting the last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II, was assassinated in 750. This is when the Abbasid caliphate began.

The end of the Abbasid era is harder to define. Though territory and power were lost to various competing dynasties from the late 10th century, there were still rulers calling themselves Abbasid caliphs in the 1200s. This essay will focus on the high point of their power—the late 8th to 10th centuries—and will look at three aspects: cities, technologies, and books.

Cities

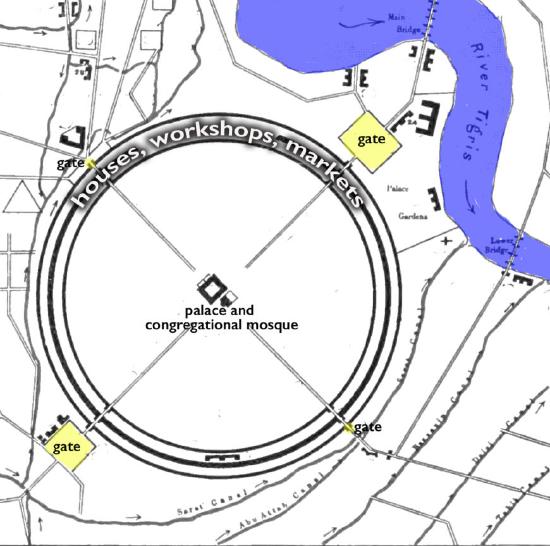

After the revolt in 750, the Abbasids moved the capital from Damascus in Syria, where the Umayyads had been based, to Kufa in Iraq. Then, in 762 the caliph al-Mansur founded a new imperial city on the banks of the Tigris—Madinat al-Salam or the City of Peace, also known as Baghdad.

The city was carefully planned to express perfection and order, as a display of the qualities of the new regime; it was circular in plan, with four main gates, one at each compass point, similar to the 3rd-century Sasanian city of Gur, whose outlines can still be seen in the fields around Firuzabad in Iran. The center of Baghdad was left largely open around the palace and congregational mosque, while the houses, workshops, and markets were arranged in a ring inside the walls.

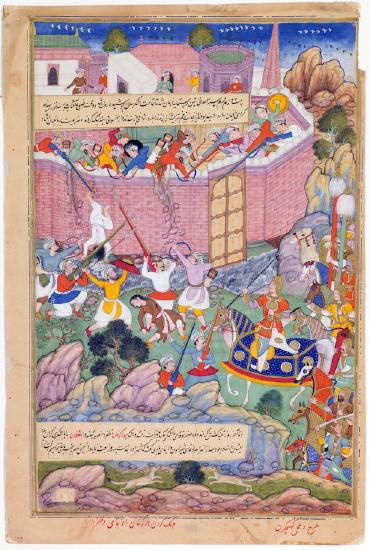

No remains of the round city have survived, partly due to the siege and assault on the city by the Ilkhanid Mongol army in 1258 (see Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)), and partly due to the construction of the modern city on top of the older structures, but we know something of its appearance from medieval descriptions. Some were written by authors born in Baghdad, such as al-Ya’qubi and al-Katib al-Baghdadi, and some by those who had moved there, attracted by the facilities for scholars, such as al-Jahiz, who reported that:

I have seen the great cities . . . in the districts of Syria, in Bilad al-Rum and in other provinces, but I have never seen a city of greater height, more perfect circularity, more endowed with superior merits or possessing more spacious gates or more perfect defenses than the [Baghdad] . . . of Abu Jafar al-Mansur.Description by al-Jahiz, reported in the Ta’rikh Baghdad (History of Baghdad) by al-Khatib al-Baghdadi [1]

Among the treasures in the palace was an automata in the shape of a tree made of gold and silver, whose branches would move as if swaying in the wind, while the model birds sitting on them would sing. [2] One of the aims of such luxury was to advertise the wealth and strength of the Abbasid caliphate to rival powers, such as the Byzantine Empire based in Constantinople—and in this the patrons were successful. After hearing an ambassador’s report of the palace and its furnishings, the mid-9th-century, Byzantine emperor Theophilus was so impressed that he commissioned one intended to imitate it, although the site is not known with certainty today.

Another early Abbasid project was the twin city of Raqqa-Rafiqa in Syria (see Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). Raqqa had existed for centuries, and in 770 al-Mansur ordered the construction of a new and more defensible settlement, Rafiqa, less than half a mile away, as part of a larger project of creating fortified sites near the border with Byzantium. The new part of the town, Rafiqa (Raqqa and Rafiqa eventually merged as one urban center) was given a substantial wall of brick, nearly three miles long, with monumental entrance gates.

In the 780s caliph Harun al-Rashid chose Raqqa-Rafiqa as his capital, and the architecture of the twinned towns took on a more elegant aspect, with enhanced decorative as well as defensive features. Archaeologists have discovered more than twenty palaces, mostly outside the walled enclosure, dating to the reigns of Harun and his son al-Mu’tasim.

The capital shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) comes from one of these palaces. It has a stylized version of an acanthus-leaf design that had been popular throughout late antiquity; in this reimagined form, the leaves also form abstract patterns. Other pieces of carved stone and molded stucco were found with similar designs, showing that the decor of the late 8th-century palaces was carefully coordinated by skilled artisans.

Samarra, founded by the caliph al-Mu’tasim in 836, was different from either of the earlier sites. Although it was the size of a city, covering more than twenty square miles, it was devoted to the Abbasid court, with palaces, pavilions, mosques, monumental avenues, barracks, gardens, pools, and three horse-racing tracks. There were also areas of more modest housing, but the heart of Samarra was ceremonial (see Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)). Despite the huge outlay of resources, the site was fully occupied for less than sixty years. The 860s saw significant political instability at Samarra caused by competing military factions in the caliphal guard, and at the death of caliph al-Mu’tamid in 892, the court moved back to Baghdad.

The fragments of painting shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\) come from the Dar al-Khilafa, the largest of the palaces. Its walls were covered with a mixture of figural frescos, stucco reliefs, ceramic tiles, and marble panels, and some of the floors were tiled with glass (see Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\)). These buildings were showcases of all the precious materials that the patrons possessed (some local, others acquired from afar), and all the arts of the skilled workers they could command.

Technologies

The grandeur of Samarra drew on the expertise of craftspeople from across the Islamic world, who had been invited or conscripted to the caliphal workshops. Raqqa-Rafiqa also had industrial areas, especially for the production of glass and ceramics. Artisans around the Abbasid courts developed new methods of production, for instance inventing recipes for glass which used plant-ash instead of natron salt, so that production was no longer restricted to areas with natural deposits of the salt.

Potters experimented with glazes, some of them trying to imitate the precious porcelain vessels from China, which were imported to the caliphate in increasing quantities from the early 9th century, along sea trade routes via Indonesia and India. The Abbasid potters did not have the materials needed to produce porcelain, but succeeded in inventing a white tin-based glaze, as on the bowl shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\). They also developed iridescent luster glazes, a technique that would go on to change ceramic production not only in the Middle East but also in medieval Europe. Although they would have been valued, lusterware plates and bowls were probably not restricted to the very rich, and were made in large quantities for sale in urban markets.

Artisans working in various materials in this period developed a new aesthetic of swirling patterns, known today as the beveled style. It was first used in the palaces of Samarra, particularly for stucco wall coverings, and it was also often used for carved wood and stone (see Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)).

The bowl shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\) is painted with a two-dimensional variant. It was made in the 10th century in Samarkand, modern Uzbekistan, which was part of the Abbasid caliphate at that time. Samarkand was also the site of the first Islamic mill for paper-making, another technology which, like porcelain, originated in China, and which changed the face of book production as paper replaced parchment and papyrus over the following centuries.

Books

Before the Islamic conquests, large parts of the caliphate belonged to the Byzantine Empire, where Greek was the dominant language, and although the language of government was changed to Arabic in the early 8th century, Greek continued to be widely spoken and written. Many Muslim patrons took an interest in classical literature—continuing a long history of interaction between Arabic and Greco-Roman cultures—and if not bilingual themselves, they commissioned translations. The trend started in the Umayyad period, for example caliph Hisham is said to have enjoyed Arabic translations of tales of Alexander the Great. Under the Abbasids there was an even greater interest in the classics, and works of philosophy, mythology, astronomy, medicine, and others were translated.

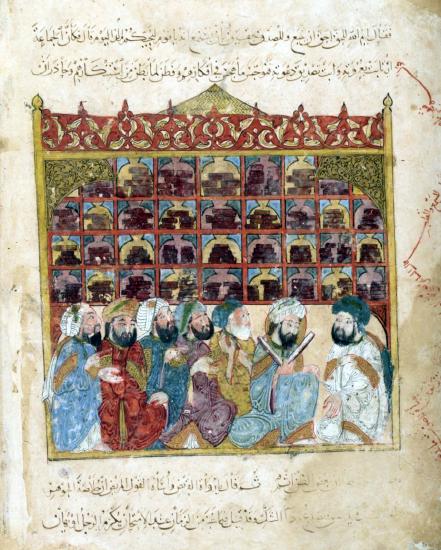

The library known as the House of Wisdom in Baghdad (bayt al-hikmah, destroyed during the Mongol siege in 1258) was a major center for this project, and there scholars from a range of cultural and religious backgrounds produced Arabic editions of Syriac, Aramiac, Hebrew, Pahlavi, and Sanskrit texts. The image in Figure \(\PageIndex{18}\) shows an idealized version of the library, with scholars engaged in debate below—their hand gestures show that it is a lively discussion—and the collected works of the institution piled up above them.

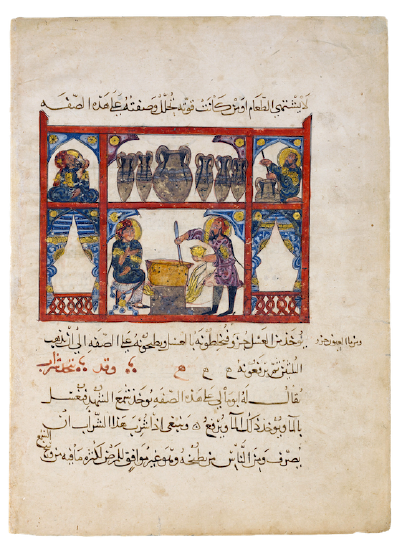

The image in Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\) comes from one of the many works translated in medieval Baghdad. It is an Arabic version of a 1st-century CE Greek medical work by Dioscorides, now generally known by its Latin name, De Materia Medica. The translation was first made in the 9th century by two Christian scholars, Stephanos ibn Basilos and Hunayn ibn Ishaq, and this specific manuscript was made in the 13th century, also in Baghdad. The illustration in Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\) shows a doctor making a medicine from honey, with a patient drinking the resulting medicine at top-left.

Abbasid scholarship was not limited to copying earlier works; for instance astronomers working for caliph al-Ma’mun in the 830s calculated the circumference of the earth, improving on ancient measurements, and established accurate figures for the phenomenon known as the precession of the equinoxes.

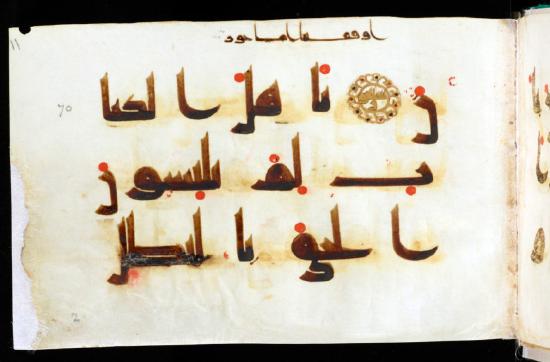

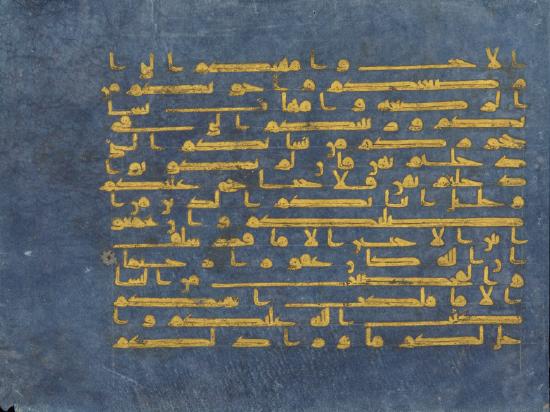

There were also developments in the format of Qur’anic manuscripts. Great emphasis was placed on the beautiful proportions of calligraphy, and a new form of script became popular; it is sometimes called Kufic, after the city of Kufa, but it was widely used across the Abbasid caliphate. Symbols for marking verses or groups of verses became more common during the 9th and 10th centuries, usually circular designs ornamented with loops, swirls or petals, and in more expensive manuscripts they were illuminated in gold, as in Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\).

The Qur’an shown Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\) was made for Amajur, Abbasid governor of Damascus in the 870s, and he donated it to a mosque in the city of Tyre in Lebanon. The script does not include all the diacritical marks used in written Arabic today, and along with the elegantly stylized letter shapes and the gilded verse marker, the effect is to make this a work of visual art just as much as a piece of text.

Artistic legacies

The artistic legacies of the Abbasid caliphate are varied. Some of the monuments described in this essay were short lived; impressive as they were, the palaces of Samarra barely lasted for two generations. But many visual and technological innovations of the period, from lusterware ceramics to “Kufic” script to the engagement with classical scientific literature, continued to be significant components of Islamic culture—and influences on surrounding cultures—for centuries to come.

Notes:

[1] Description by the author al-Jahiz (776–869) reported in the Ta’rikh Baghdad (History of Baghdad) by al-Khatib al-Baghdadi (1002–71); quoted in Jacob Lassner, The Shaping of ‘Abbasid Rule (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), p. 167.

[2] Al-Khatib al-Baghdadi, Ta’rikh Baghdad (History of Baghdad); quoted in Oleg Grabar, The Formation of Islamic Art (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1987, p. 159).

The Vibrant Visual Cultures of the Islamic West, continued

by Dr. Sahahat Adil

Competing Identities

After the fall of the Umayyads of al-Andalus, Iberia saw the rise of Taifa/Party Kingdoms. These kingdoms arose in the eleventh century in the political vacuum created by the collapse of the Umayyad state in Córdoba. These rival kingdoms were independently governed city-states and often competed with one another militarily and in terms of cultural production. One of these city-states was located in Saragossa, and its palace is a stunning example of the artistic developments of Islamic visual culture on the Iberian Peninsula.

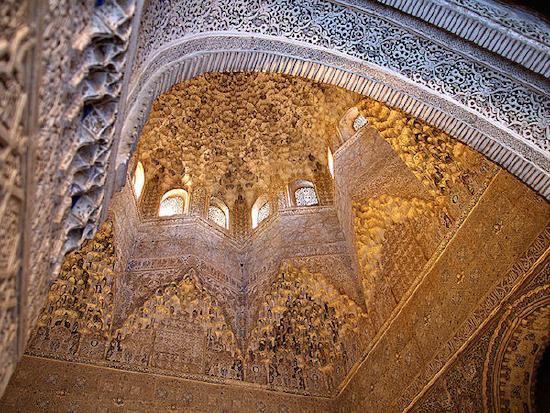

The Aljafería Palace has numerous arches, much like the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba and Madinat al-Zahra, but the decorative elements are striking and represent a notable departure from earlier centuries (see Figures \(\PageIndex{21}\) and \(\PageIndex{22}\)). For example, stucco, which is known as yesería, appears as complex vegetal and floral motifs. Stucco was less commonly found in the visual culture of the Umayyads of the Islamic West, though the motifs themselves were commonplace.

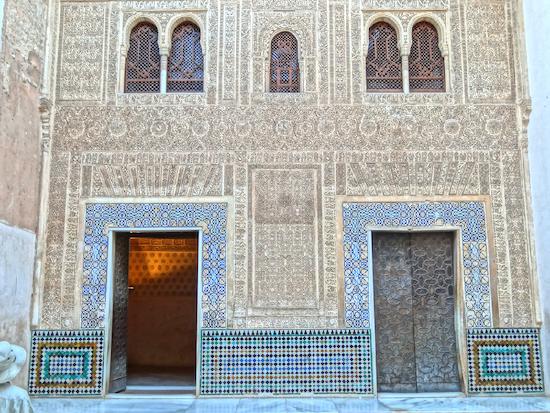

Stucco decoration was also an integral part of the artistic toolkit of the Mudéjar populations (Muslims living under Christian rule on the Iberian Peninsula), and these decorations reached their pinnacle under the Nasrids. Many examples of these stucco decorations can also be found at the Alhambra.

Despite the early strength of Islamic rule on the Iberian Peninsula, the declaration of a caliphate, the tolerance of limited multiculturalism—within a religious and social hierarchy—and the pressure of the Reconquista from the Catholic north led to a reversal of fortune for the Muslims of al-Andalus.

Before the Reconquista was completed in 1492, two powerful dynasties emerged in Morocco that served as a countervailing force against the military pressure exerted by Christians in the north. The Almoravids and the Almohads, each eventually conquered parts of the Iberian Peninsula and delayed the Christian reconquest. The visual cultures of these dynasties, each originating in Morocco, are worth keeping in mind since they both constructed architectural monuments in North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula—creating a cohesive architectural heritage spanning the Strait of Gibraltar.

One Almohad monument worth considering is a mosque called Tin Mal, situated in the High Atlas Mountains. The minaret of the mosque is striking, as it takes a quadrangular form as opposed to a rounded one, echoing other minarets and towers erected by the Almohad dynasty.

Although the interior features vegetal patterns, the exterior façade of the mosque is generally devoid of decorative features, reflecting the sobriety of many monuments produced by the Almohads due to their ideological notions of religious and social purification.

Two minarets, La Giralda in Seville (part of the Great Mosque of Seville under the Almohads) and the tower of the Qutubiyya Mosque (also spelled Koutoubiya) in Marrakesh, were both constructed under the Almohads. Both are tall rectangular towers strikingly similar to their counterpart at Tin Mal. The surface decoration found on La Giralda is intricate and worth observing, particularly because much of it has survived since the original construction.

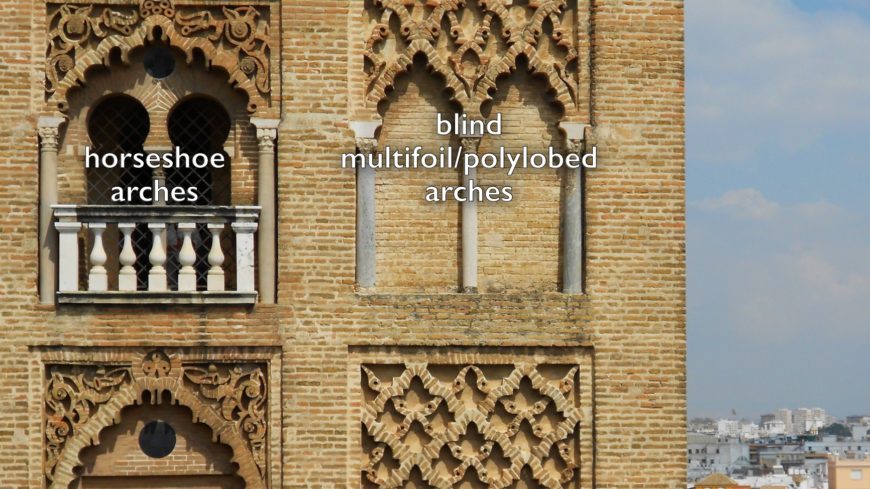

This surface poses a striking visual contrast between smooth and uninterrupted stone in much of the lower part of the tower and blind multifoil/polylobed arches as well as horseshoe arches, some of which are set on marble columns. Meanwhile, the minaret of the Qutubiyya features similar components, including the blind arches.

Both of these minarets reflect the continuity in visual culture across the Strait of Gibraltar. At the same time, they also reflect the subsequent histories of each region. While La Giralda was converted into a bell tower for Seville’s cathedral after the Reconquest, the tower at the Qutubiyya Mosque in Marrakesh remains a minaret for a vibrant central mosque to this day. While bells toll from La Giralda, the Islamic call to prayer can be heard from the Qutubiyya’s minaret. While time and historical circumstance has altered the function of one of these towers, their shared visual heritage remains unmistakable.

Almohad coins, also known as masmudia, are another important art form of medieval Iberia. Like pyxides, they were desirable outside of their Islamic context and also circulated in Christian-controlled northern Iberia, likely for reasons of prestige. A ten-dinar coin made in Morocco was modified so that it could be worn as jewelry (see Figure \(\PageIndex{30}\)). One side of the coin features the Islamic declaration of faith (basmala) as well as the name of the prince under whom the coin was issued and that of his father, while the other side of the coin states the names of important Almohad leaders.

The use of a simple square, containing and surrounded by calligraphy, and minimal additional embellishment align with the strict religious outlook and vision of the Almohads. The Almohads tried to streamline the practice of Islam on the Iberian Peninsula, and their political actions, texts, and visual culture testify to this fact.

Locating Religious Diversity

In addition to the many Muslims who lived in the Iberian Peninsula after its conquest in the early eighth century, Christians and Jews made important contributions to the development of the art and architecture of the Peninsula. San Miguel de Escalada, a Christian monastery in northern Iberia, was constructed in the tenth century by monks who fled Córdoba after the Islamic conquest of the city (see Figure \(\PageIndex{31}\)). Although San Miguel de Escalada was constructed in a region controlled by Christians, it is considered Mozarabic because the monks responsible for its reconstruction had come from Córdoba. Elements of the monastery clearly reflect aspects of the Islamic art of al-Andalus, even though this was explicitly constructed as a Christian religious space. For example, the monastery’s interior and exterior feature rows of horseshoe arches, much like those at Madinat al-Zahra. Yet its interior structure features elements such as an apse and a nave, which are central components of Christian church architecture in the Iberian Peninsula and more broadly. Many of the columns found on this site are Roman spolia, which demonstrates the incorporation of earlier visual heritage.

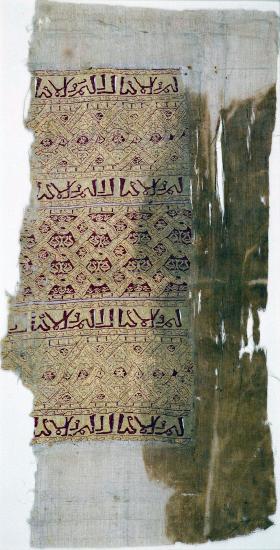

Artistic patronage could transcend religious and/or cultural lines. A textile fragment found buried in a tomb of Don Felipe Infante (who died in 1274 and was son of Ferdinand II and brother of Alfonso X, both thirteenth-century Christian kings of Castile) features floral patterns such as rosettes and Arabic writing in a calligraphic script known as kufic. Like the coin discussed earlier, this textile fragment demonstrates how artistic styles and language were valued across religious and cultural lines, even during, and maybe as a result of, socio-political tensions.

Jewish communities were also integral to the diverse culture of al-Andalus. The Ibn Shoshan Synagogue (renamed Santa María la Blanca when it was converted into a church) and the synagogue of El Tránsito in the city of Toledo both demonstrate this diversity beautifully. While the former was constructed in the twelfth century during the Almohad era, the latter was constructed in the fourteenth century after the Reconquista had already brought Toledo under the rule of Catholics, in this case under Peter of Castile, who was known as Peter the Cruel.

Both synagogues feature stucco, which was now a prominent building and decorative material in architectural structures throughout the region, regardless of religious or cultural affiliation. They also consist of multiple naves divided by arches. The Ibn Shoshan Synagogue (now more commonly known by the church’s name) was built by Mudéjar craftsmen, who used yesería decoration heavily. Like many mosques, synagogues were also often converted to churches after the Reconquista.

The Castilian synagogues (such as Santa María la Blanca) of the thirteenth century tend to be similar to mosques architecturally. Jews who left al-Andalus and moved north likely brought these building traditions with them. This synagogue has five naves, and the central nave is slightly wider than the other four. A unique feature of the synagogue was likely the Hekhál—also known as the Torah ark to house the scrolls of the Torah—which is unfortunately no longer extant. In contrast, El Tránsito follows a distinct pattern of organization, featuring a large open space rather than space divided by naves. This synagogue combines elements from both Islamic and Christian artistic traditions, such as vegetal patterns from the former and a coat of arms from the latter (this coat of arms was attributed to the Halevi family, an important Jewish family of Iberia).

In spite of the rich legacy of Jews on the Iberian Peninsula, their prospects turned grim as the centuries progressed with political enactments, forced conversions, and massacres characterizing the Jewish experience in Iberia in the fourteenth century.

Visual Culture in an Era of Constriction

The Nasrids were the last Islamic dynasty in al-Andalus. While the Alhambra is the most well-known structure of this dynasty, domestic spaces of a less public nature reveal how people, just below the highest social classes, lived their day-to-day lives. Daily routines can be imagined in a wholly different way through these somewhat more modest domestic spaces.

The Albaycín neighborhood in Granada, which overlooks the Alhambra, demonstrates how elite classes in al-Andalus lived. In particular, the Zafra House in Albaycín has a central courtyard that is surrounded by rooms and consists of three floors. Each side of the patio on the ground floor has a portico, and each portico has marble columns and capitals with arches. In addition to the ground floor, there are two additional galleries above the porticos on the ground floor that span the same length as the porticos. This layered internal space is revealed to visitors upon entry without the slightest hint of this complexity revealed from the external façade. This outward homogeneity, in a way, maintained a heightened sense of privacy about how individuals carried on their daily lives. The external plainness, in contrast with the internal complexity in terms of organization, is an element of domestic architecture from many other parts of the Islamic world and demonstrates the extent of architectural continuities across geographies that were inspired by a shared religious tradition and social ethos.

The Nasrids ruled during a period of increasing constriction for the Muslims and Jews of Iberia. By the thirteenth century, when the Nasrids came to power in southern Iberia, the borders of al-Andalus looked very different from the early centuries when Islamic power extended into the northernmost reaches of the Iberian Peninsula. The Reconquista had been driving southward, strengthened by alliances among Catholic monarchs as well as the support of the papacy in light of the broader framework of the Crusades. During the Nasrids’ rule, all that remained of al-Andalus was the Kingdom of Granada. Not only did the Reconquista take lands that had been under Islamic rule for hundreds of years, but it also sought to suppress non-Catholic identities through inquisitorial tribunals (first established in 1487 under Ferdinand and Isabel), political decrees, and violence, which were directed towards Muslims, Jews, and anyone outside the fold of mainstream Catholicism (as defined by Spain’s religious and political leadership and also, more broadly, the papacy in Rome under the backdrop of the Crusades).

Despite these socio-political constraints, visual culture continued to prosper. Lusterware, a type of pottery that earns its name from its lustrous sheen, was common at this time. Artists who produce lusterware finish their pieces with the application of metallic glazes, a technique refined in the Umayyad and Abbasid eras. The oxidation of these glazes results in a gorgeous iridescence. A deep dish from The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York shows a palm tree in the middle of the plate with Arabic calligraphy surrounding it. Lusterware was exported throughout Iberia and abroad. People continued to value what they could see, hold, and have, despite political dynamics. Moriscos were actively involved in the production of lusterware on the Iberian Peninsula, and evidence of lusterware from Iberia in the Americas speaks to the movement of exiled populations across the Atlantic.

These buildings and works of art demonstrate a remarkable degree of cultural exchange and interaction that flourished in the western Mediterranean in the medieval era. Political realities seldom matched up with the patronage and production of art and architecture. Exchange and interaction did not stop on the coasts of Europe or Africa either, but rather flourished across the Strait of Gibraltar, a bridge that has long served to connect people, ideas, and objects. Even in contemporary times, artists and artisans continue to produce art inspired by the historical art of Islamic Iberia.

At the same time, the rich history of Iberia demonstrates that it was also equally complex and dark. While many individuals of Jewish background, for example, rose to high professional positions, complete and utter equality was an unrealized aspiration, given the value placed on religious hierarchy and stratification as articulated by the Pact of Umar (an early Islamic document). In its time, al-Andalus posed an example of the possibilities of religious tolerance, diversity, and coexistence, but it also showcased its limitations.

The Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm (the Church of Santa Cruz), Toledo

by DR. Razan Francis

On the northern fringes of Toledo, Spain, the small Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm tells a compelling story about the city’s medieval period and its transition from Muslim to Christian hands. The mosque is located adjacent to one of Toledo’s oldest city gates—Bāb al-Mardūm (Puerta Mayordomo)—which once gave access from the north to the city (today’s neighborhood of San Nicolás). The mosque is one of the few surviving structures from the Islamic period in al-Andalus. Its later conversion to a church, at a time of Christian-Muslim conflict, illustrates how Toledo’s visual culture transcended the religious differences of its Jewish, Christian, and Muslim residents.

Toledo: brief background

Muslims invaded the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal today) in 711 CE, and ruled Toledo until its takeover in 1085 by the Christian army of the king of Castile, Alfonso VI. Prior to the Muslim conquest of the city, Toledo had been the capital of the Visigothic kingdom since the fifth century; before that it was under Roman rule. The Muslim conquest of the city was part of an unprecedented expansion of the Umayyad caliphate, centered in Damascus (Syria), which in 711 reached the land of Sindh (southeastern Pakistan today) in the East, and North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula in the West. After the Umayyads were overthrown by the Abbasids in 750, a survivor of the Umayyad dynasty—’Abd al Rahman I—escaped and reached the Iberian Peninsula. There, he established at Córdoba a Muslim state (emirate), later declared a caliphate in 929. The Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm was built in the last years of the Umayyad caliphate in al-Andalus (which fell in 1031), when Toledo was the center of its northern dominions.

Inscription, patron, and builder

Importantly, the mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm was one of many private institutions erected by elite, wealthy Muslims—unlike large congregational, or Friday, mosques that were commissioned by the state. It probably functioned as a small oratory that also promoted learning, and received local and visiting scholars and students. In the Islamic world, a mosque functioned both as a place for worship as well as learning; scholars often sat in a designated space in the mosque, where students could find them.

Before entering this small mosque, a visitor would have seen a Kufic inscription on the upper frieze of its southwest façade. The inscription informs the viewer about the mosque’s patron, builder, and year of completion before they even enter the space:

In the name of God the Compassionate, the Merciful, Aḥmad ibn Ḥadīdī caused this mosque to be built, with his own funds, hoping through this to receive eternal compensation from God. It was completed with the aid of God, under the direction of the architect Musa ibn ‘Alī, and of Sa‘āda, concluding in [the month of] Muharram of the year three hundred and ninety [999/1000].

As the Andalusī historians Ibn Bassām (d. 1147) and Ibn al-Khaṭīb (d. 1347) report, the patron, Ibn Ḥadīdī belonged to one of Toledo’s most influential families; they served as judges and ministers under Toledo’s rulers (the Dh’ul-Nūnids).

Plan, spatial arrangement, and façades

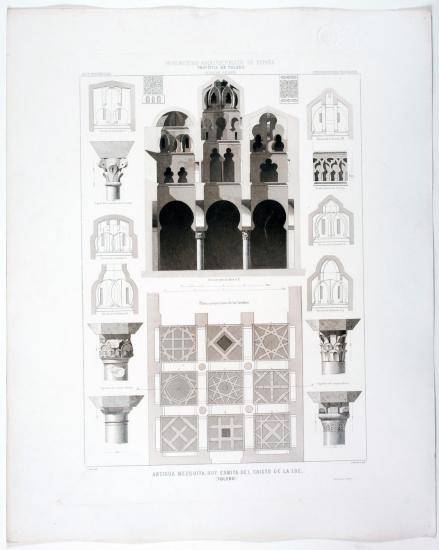

Despite its small size, the mosque introduces a tight geometric plan and a novel spatial arrangement. The use of bricks to sculpt the façade through creating multiple brick planes, as if it is made of layers, is also a novelty. Once inside the space, it almost seems as if the architect converted the maqsura of the Great Mosque in Córdoba into a freestanding mosque (see Figure \(\PageIndex{41}\)).

The mosque comprises a stone foundation of rubblework that forms a base to its brick walls. Square in plan (8 x 8 meters; Figure \(\PageIndex{42}\)), it consists of nine equal square bays, demarcated by four central marble columns. The columns and their capitals are spolia, taken from a now-destroyed Toledan Visigothic church. The horseshoe arcades render this small oratory a miniature hypostyle hall.

This is certainly not the first incident where Muslims reappropriated spolia—in fact, we could look at the the 110 Visigothic and Roman marble columns used in the first phase of the Great Mosque of Córdoba or the Roman tombstones inserted at the base of the minaret of Seville’s Great Mosque (now the Giralda of Seville Cathedral). Building with spolia speeded construction. Such incorporation, profusely practiced worldwide, may have symbolized acceptance of past authority and established continuity with the local heritage by preserving spolia’s sacredness and charged history in the new architectural settings.

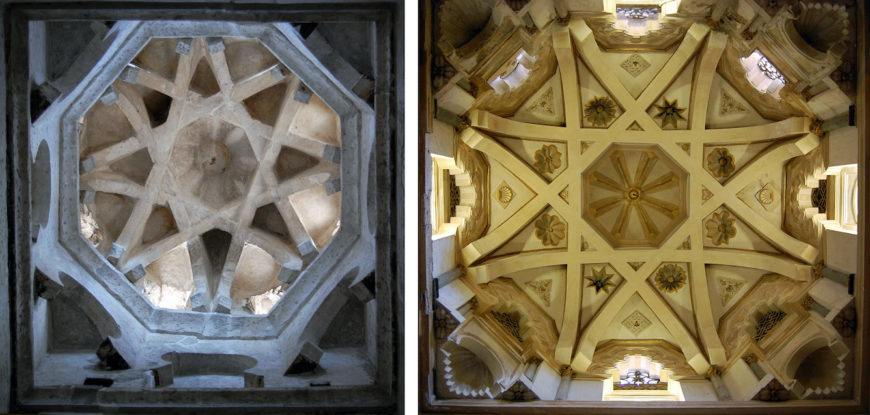

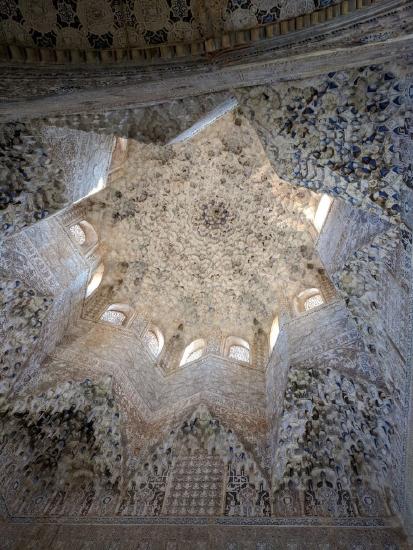

Adding to the Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm’s richness, each of the nine square bays is surmounted by a soaring ribbed dome of a different vaulting design, evoking those covering the maqsura of the Great Mosque of Córdoba (see Figure \(\PageIndex{43}\)). Just as in the maqsura of Córdoba’s Great Mosque, where this type of vaulting first appeared on the peninsula almost fifty years earlier (960s CE), each square bay carries a multi-tiered set of lobed arches that rises high, and is surmounted by a dome of interlacing ribs. While only three such domes cover the maqsura, those of Bāb al-Mardūm replicate these three, and introduce six novel designs that nearly exhaust the whole potential of such vaulting. The most common design creates, through squinches, an octagonal base over the square bay. From this octagonal base, two sets of ribs rise either from the middle or the corner of the octagon, and extend to another, opposite side of the octagon. From this spatial interlacing of the ribs, a central, smaller geometric polygon is created, and is usually carved in the shape of a scalloped miniature dome. Showing remains of paint, the mosque’s domes may have once been polychromatic (many colored).

The mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm once stood as a pavilion-like structure open on three sides (now closed in), except for the mihrab on the southeast wall, where the mihrab niche facing Mecca used to be. The exterior facades are enlivened by the use of bricks in different thicknesses to subtly create recessed and projecting planes. The main southwest façade, overlooking the street has three different arched entryways: horseshoe, right; semicircular, center; and lobed, left (see Figure \(\PageIndex{44}\)). On top of these doors, a series of blind horseshoe arches project and interlace in a similar fashion to the interior screens marking the mihrab aisle and the maqsura of the Great Mosque of Córdoba.

Above these blind arches, brick units laid in an angle create a sawtooth-pattern frame that inscribes a diamond-like perforated brick net. This frieze is surmounted by the dedicatory inscription (see Figure \(\PageIndex{45}\)), whose angular letters are also created by laying the bricks in both horizontal and vertical alignments. Even the series of corbels that hold the roof, on top of the inscription, are produced by stacking and recessing the bricks.

As one moves around the mosque, the northwest façade features, on its lower level, three recessed horseshoe arched entryways, each framed by a rounded semicircular arch (see Figure \(\PageIndex{46}\)).

The upper level consists of six horseshoe windows of alternating voussoirs of red brick and greyish stone, framed by projecting trilobed arches (see Figure \(\PageIndex{47}\)). This use recalls, albeit on a smaller scale, the alternating brick and stone voussoirs of the interior double arcades of the Great Mosque of Córdoba. The mosque is a powerful demonstration of decorative brickwork. Its architectural reference to the visual expressions of the Great Mosque of Córdoba certainly reflected Ibn Ḥadīdī’s prominence and his elevated status.

Conversion into the Church of Santa Cruz

When Alfonso VI seized Toledo from the Muslims in 1085, and made it the capital of the kingdom of Castile, Toledo’s congregational mosque was almost immediately converted into a church (later destroyed to become a cathedral). While the congregational mosque stood at the center of the city, around which the city’s markets and institutions were formed, the Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm, was on the city’s edge.

For almost a hundred years after the conquest, the Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm continued to serve the now much smaller Muslim community. Shifting the Muslim place of worship from the city’s center to its periphery minimized Muslim visibility in the city, as the congregational mosque had constituted the place for Muslims’ social gathering and the starting point of processions (such as funerals) to the different parts of the city.

In 1183, the mosque was given to the Order of the Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem (also known as Hospitalers), a military religious order, founded in Jerusalem in the 11th century that came to Spain to fight Muslims. In 1186 the mosque was consecrated as a Christian chapel and dedicated to the Holy Cross (Santa Cruz), which was when, as most historians agree, the architectural conversion of the mosque took place (see Figure \(\PageIndex{48}\)).

The conversion from mosque to church was easy due to the architectural adaptability of mosques—in al-Andalus, they were, after all, hypostyle structures (having a roof supported by several rows of pillars) with no images offensive to Christianity (the depiction of animate beings is prohibited in Islamic religious spaces). Conversion often only entailed a change to an East-West orientation and a “cleansing” ritual. Politically and theologically, conversion signaled Christianity as the new religious authority. Moreover, as most mosques either stood on the site of an earlier Visigothic church or were themselves converted churches, their (re)conversion into churches was seen as a legitimate act that returned a monument to its original Christian state. However, ecclesiastical and royal figures also admired mosques (and Islamic palaces) for their artistic refinement.

The conversion of Bāb al-Mardūm to a church entailed changing the mosque’s orientation by introducing a shallow transept and semicircular apse, which was needed for the altar (see Figure \(\PageIndex{49}\)). Finally, fresco paintings were added to the interior.

Although the new addition has fewer openings, featuring mainly blind arcades, it could be considered a variation on the corresponding architectural elements of the earlier mosque. It seemingly continues the same brick construction technique to texture the façades. On its lower part, a semicircular blind arcade of recessed planes wraps around the apse area, while on the upper level, a multi-lobed pointed blind arcade frames a recessed keel-shaped arcade. The transept (crossing) portion, situated between the earlier mosque and the new apse, slightly projects almost at wall’s width, signaling a rupture between the old and new, so as to remind the viewer of the existence of two phases: before and after the conquest.

On the interior of the apse’s semicircular dome, the Christ as Pantokrator (Christ in Majesty) is depicted on a background of blue skies and stars, surrounded by the symbols of the four Evangelists, of which only Mark and John survive (see Figure \(\PageIndex{50}\)). The apse’s lower horseshoe niches once held images depicting saints. The arch leading to the apse area is decorated on the outside with a painted cursive (naskh) Arabic inscription in red and black, featuring the phrase, “al-yumn wa-l-iqbāl” (prosperity and good fortune). This phrase commonly appeared in contemporary Islamic architecture and circulated on luxury portable objects produced in Spain, and on tenth-century textiles made in Fatimid Egypt (see Figure \(\PageIndex{51}\)).

The image of Christ Pantokrator, one of the most best-known depictions of Christ, showcases the power of Christianity and the Church. This message of power—and the triumph of Christianity over Islam—is further conveyed by the Latin inscription on the lower register of the apse from Matthew 25:34: “Then the king will say to those on his right, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father. Inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world.’”

Given the military nature of the Order of Saint John, and its activity in the crusade against Muslims, one would expect the mosque to have been destroyed. Preserving the mosque may have symbolized triumph and served as a visual manifestation of a trophy or spoil of war. Yet, analyzing the architectural conversion solely from such a triumphalist standpoint overlooks other aspects specific to Toledo’s history and building tradition.

A note on the term Mudéjar

The converted building has often been labeled “mudéjar,” a scholarly term denoting the incorporation of the same architectural elements that were used in the original mosque and in other Andalusī buildings. The so-called mudéjar elements that the mosque displays are its construction in brick, the rigorous use of horseshoe and lobed arches, and its Arabic inscriptions. In other locales, “mudéjar” elements included geometric and vegetal decorative motifs (often executed in stucco), geometric glazed tiles or wooden ceilings, interlacing arches, or ribbed domes.

The term mudéjar is problematic though because, among other things, its original meaning signified Muslims living under Christian rule. The word mudéjar comes from mudajjan, which in Arabic could mean “one permitted to stay” / “one left behind,” or “subjugated”/ “domesticated”/ “tamed.” The term’s use in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to describe certain aspects of art and architecture suggested that adopting the architectural and artistic elements of the foe (the Muslims) by Christian patrons or in Christian-ruled territories paralleled the Christian reacquisition of the land from Muslims. It also associated the art and architecture produced in Toledo, and in al-Andalus more generally, with the predominant religion of Islam, and implied that the building workforce in the lands newly conquered by Christians was and continued to be Muslim (mudéjar). However, in a city like Toledo, where Christians, Muslims, and Jews lived together for almost five centuries before the Christian reconquest, it is difficult to attribute an architectural style only to Muslims. Rather, it is more reasonable to think that it expressed the identity of all city inhabitants. Consequently, we should not assume that those who executed the new additions to the Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm were Muslims, as the builders also may have been Christians or Jews.

It is true that the mural program and the new orientation of the church came to assert the Christian faith, especially when figurative art was prohibited in a mosque, but the display of the Arabic inscriptions may allude to a shared culture, language, and taste. After all, Arabic was spoken by members of the city’s three religious groups and was, certainly at this time, not perceived as foreign. Numerous surviving architectural works and objects from the medieval period include multiple languages and testify that Arabic was not the ‘property’ of Muslims. Take for example the Hebrew and Arabic woven into the walls of Toledo’s mid-fourteenth century Synagogue of Samuel Halevi Abulafia (see Figure \(\PageIndex{52}\)); the bi-lingual Christian tombstones from twelfth- and thirteenth-century Toledo; or the Latin, Castilian, Arabic, and Hebrew marble epitaphs of King Fernando III’s tomb (c. 1252) in Seville Cathedral. Of course, the interpretation of the use of Arabic varies based on the specific context.

The Mosque of Bāb al-Mardūm—and its conversion into the Church of Santa Cruz—is an example that embodies the multi-religious reality of medieval Spain, where architecture and art were informed by the cultural complexity of such a dynamic setting.

Medieval synagogues in Toledo, Spain

by Dr. Diane Reilly

By the time the first surviving synagogues were built in Spain, Jews had lived there for more than a thousand years. The first Jews likely arrived on the Iberian peninsula among the Roman conquerors and colonizers who flowed there in the first century CE. Jews were persecuted by Christians during the Late Antique period (beginning in the 4th century), but when Muslim rule was established in 711, the legal and economic status of Jews improved. Often well integrated into the governments and economies of the cities in Muslim Al-Andalus, many Jews spoke Arabic and wore the same clothes as their Muslim neighbors.

Although population estimates for pre-modern periods are notoriously unreliable, one scholar has estimated that the Jewish population of Spain grew to be larger than the Jewish populations of every other part of the medieval world combined. Given the size and wealth of the Spanish Jewish communities of Al-Andalus, we can be certain that they built many synagogues in the quarters of the cities where they lived, but none survive from before the south of Spain was reconquered by northern, Christian rulers. Spain’s most remarkable medieval synagogues are found in former Islamic capitals, but they were built after these cities were again governed by Christians.

By the late Middle Ages, there were at least eleven synagogues in the city of Toledo in central Spain (see Figure \(\PageIndex{53}\)). Two of these—the Samuel Halevi Abulafia synagogue (Figure \(\PageIndex{52}\)) and the Ibn Shoshan synagogue (Figure \(\PageIndex{54}\))—stand only a few blocks apart in the old Jewish quarter. Both synagogues display a style inspired by the Islamic buildings that surrounded them, sometimes called Mudéjar. This style was used by Muslim, Christian, and Jewish patrons and builders living in parts of Spain formerly governed by Muslims. The earlier Muslim builders had themselves borrowed from the cultures that preceded their arrival by including details that had been popular with Romans and Late Antique Christians in Spain, such as reused columns, Corinthian capitals and horseshoe arches.

A twelfth-century synagogue for Toledo’s Jewish community

The Ibn Shoshan Synagogue was likely first built around 1180, and was probably renovated by a member of the Spanish royal court in the thirteenth century before it was converted into a church (renamed Santa María la Blanca) in 1411 (see Figure \(\PageIndex{55}\)). The bimah, Torah ark, and seats for the congregation were destroyed when the building was converted into a church. All that remains from the synagogue is the architecture.

The interior is divided into five aisles by four rows of stout octagonal piers (see Figure \(\PageIndex{56}\)). The piers carry rows of capitals decorated with stucco pinecones and volutes, surmounted by giant horseshoe arches.

Above the arches are layers of low-relief stucco tendrils and roundels, scallop shells, geometric interlacing, and rows of blind arches with multiple lobes (called poly-lobed arches), a wealth of surface decoration that recalls the type found in earlier Spanish buildings like the Great Mosque at Cordoba.

We know this wasn’t simply a local Toledan style, but one popular in other parts of Spain, because the Jewish community to the north in Segovia built a very similar synagogue, now destroyed, at almost the same time.

A private synagogue for a royal advisor

Almost two hundred years later, around 1360, a new synagogue was built in a different but related style by Samuel Halevi Abulafia (Figures \(\PageIndex{52}\) and \(\PageIndex{57}\)), treasurer and advisor to the Spanish King Pedro I of Castile. Unlike the Ibn Shoshan synagogue, this one was private, and attached to Halevi’s palace, although it would have been a significant monument in the neighborhood given its height.

Instead of being divided into aisles by rows of arches, the Samuel Halevi Abulafia synagogue (later known as the church of El Transito de Nuestra Señora) is dominated by a soaring, open hall that is oriented towards a triple-arched Torah niche. The upper parts of the interior walls and the wall surrounding the Torah niche are blanketed with low-relief stucco decoration.

Right underneath the decorative wooden ceiling are ranks of colonnettes supporting poly-lobed arches that hug the wall, very similar to those at the Ibn Shoshan synagogue nearby. Below these are geometrically organized patterns of leaves, flowers, scallop shells, and interlacing tendrils, as well as the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Castile, a three-turreted castle (see Figure \(\PageIndex{58}\)). A wealth of Hebrew and Arabic inscriptions praise King Pedro, the building’s architect, Don Meir Abdeil, and the royal treasurer and patron of the synagogue, Samuel Halevi, who is described as “prince among the princes of the tribe of Levi.” Inscriptions also quote literary and religious texts, including the Bible and the Qur’an.

This was the same style that King Pedro (who was Catholic) favored in his own palace architecture, making it a decorative language common to the Muslim, Christian and Jewish elites. Samuel may have wanted to celebrate his own integration into the power center of the kingdom by imitating its court style, but unfortunately his success was short-lived. Soon after the synagogue was completed, Pedro had him arrested, tortured, and executed.

Though the Jewish population in Spain was increasingly persecuted and finally in 1492, officially banished (unless they converted to Christianity), these synagogue structures attest to their long presence, and to the close interconnections between Muslim, Jewish, and Christian cultures in medieval Spain.

The Alhambra

by Dr. Shadieh Mirmobiny

The Alhambra in Granada, Spain, is distinct among Medieval palaces for its sophisticated planning, complex decorative programs, and its many enchanting gardens and fountains (see Figure \(\PageIndex{59}\)). Its intimate spaces are built at a human scale that visitors find elegant and inviting.

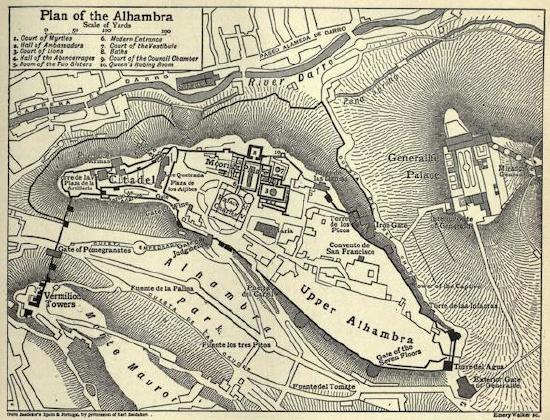

The Alhambra, an abbreviation of the Arabic: Qal’at al-Hamra, or red fort, was built by the Nasrid Dynasty (1232-1492)—the last Muslims to rule in Spain. Muhammad ibn Yusuf ibn Nasr (known as Muhammad I) founded the Nasrid Dynasty and secured this region in 1237. He began construction of his court complex, the Alhambra, on Sabika hill the following year (see Figure \(\PageIndex{60}\)).

1,730 meters (1 mile) of walls and thirty towers of varying size enclose this city within a city. Access was restricted to four main gates. The Alhambra’s nearly 26 acres include structures with three distinct purposes, a residence for the ruler and close family, the citadel, Alcazaba—barracks for the elite guard who were responsible for the safety of the complex, and an area called medina (or city), near the Puerta del Vino (Wine Gate), where court officials lived and worked.

The different parts of the complex are connected by paths, gardens and gates but each part of the complex could be blocked in the event of a threat. The exquisitely detailed structures with their highly ornate interior spaces and patios contrast with the plain walls of the fortress exterior.

Three palaces

The Alhambra’s most celebrated structures are the three original royal palaces. These are the Comares Palace, the Palace of the Lions, and the Partal Palace, each of which was built during 14th century. A large fourth palace was later begun by the Christian ruler, Carlos V.

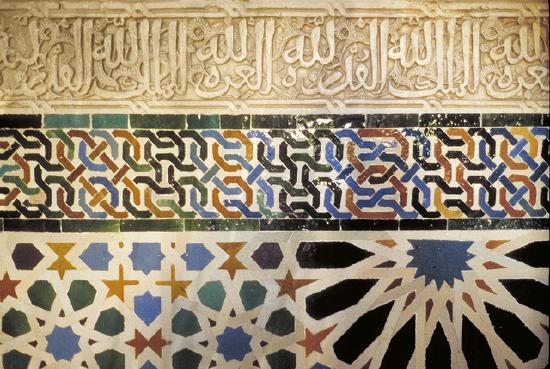

El Mexuar is an audience chamber near the Comares tower at the northern edge of the complex. It was built by Ismail I as a throne room, but became a reception and meeting hall when the palaces were expanded in the 1330s. The room has complex geometric tile dadoes (lower wall panels distinct from the area above) and carved stucco panels that give it a formality suitable for receiving dignitaries (see Figure \(\PageIndex{61}\)).

The Comares Palace

Behind El Mexuar stands the formal and elaborate Comares façade set back from a courtyard and fountain (see Figure \(\PageIndex{62}\)). The façade is built on a raised three-stepped platform that might have served as a kind of outdoor stage for the ruler. The carved stucco façade was once painted in brilliant colors, though only traces remain.

A dark winding passage beyond the Comares façade leads to a covered patio surrounding a large courtyard with a pool, now known as the Court of the Myrtles (see Figure \(\PageIndex{63}\)). This was the focal point of the Comares Palace.

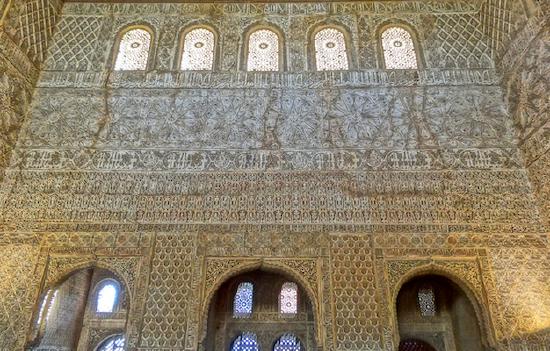

The Alhambra’s largest tower, the Comares Tower, contains the Salón de Comares (Hall of the Ambassadors), a throne room built by Yusuf I (1333-1354). This room exhibits the most diverse decorative and architectural arts contained in the Alhambra.

The double arched windows illuminate the room and provide breathtaking views. Additional light is provided by arched grille (lattice) windows set high in the walls. At eye level, the walls are lavishly decorated with tiles laid in intricate geometric patterns. The remaining surfaces are covered with intricately carved stucco motifs organized in bands and panels of curvilinear patterns and calligraphy (see Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

Palace of the Lions

The Palacio de los Leones (Palace of the Lions) stands next to the Comares Palace but should be considered an independent building. The two structures were connected after Granada fell to the Christians.

Muhammad V built the Palace of the Lions’ most celebrated feature in the 14th century, a fountain with a complex hydraulic system consisting of a marble basin on the backs of twelve carved stone lions situated at the intersection of two water channels that form a cross in the rectilinear courtyard (see Figure \(\PageIndex{65}\)). An arched covered patio encircles the courtyard and displays fine stucco carvings held up by a series of slender columns. Two decorative pavilions protrude into the courtyard on an East–West axis (at the narrow sides of the courtyard), accentuating the royal spaces behind them.

To the West, the Sala de los Mocárabes (Muqarnas Chamber), may have functioned as an antechamber and was near the original entrance to the palace (see Figures \(\PageIndex{66}\) and \(\PageIndex{67}\)). It takes its name from the intricately carved system of brackets called “muqarnas” that hold up the vaulted ceiling.

Across the courtyard, to the East, is the Sala de los Reyes (Hall of the Kings), an elongated space divided into sections using a series of arches leading up to a vaulted muqarnas ceiling; the room has multiple alcoves, some with an unobstructed view of the courtyard, but with no known function.

This room contains paintings on the ceiling representing courtly life. The images were first painted on tanned sheepskins, in the tradition of miniature painting. They use brilliant colors and fine details and are attached to the ceiling rather than painted on it.

There are two other halls in the Palace of the Lions on the northern and southern ends; they are the Sala de las Dos Hermanas (the Hall of the Two Sisters) and the Hall of Abencerrajas (Hall of the Ambassadors). Both were residential apartments with rooms on the second floor. Each also have a large domed room sumptuously decorated with carved and painted stucco in muqarnas forms with elaborate and varying star motifs.

The Partal Palace

The Palacio del Partal (Partal Palace) was built in the early 14th century and is also known as del Pórtico (Portico Palace) because of the portico formed by a five-arched arcade at one end of a large pool. It is one of the oldest palace structures in the Alhambra complex.

Generalife

The Nasrid rulers did not limit themselves to building within the wall of the Alhambra. One of the best preserved Nasrid estates, just beyond the walls, is called Generalife (from the Arabic, Jannat al-arifa). The word jannat means paradise and by association, garden, or a place of cultivation which Generalife has in abundance. Its water channels, fountains and greenery can be understood in relation to passage 2:25 in the Koran, “…gardens, underneath which running waters flow….”

In one of the most spectacular Generalife gardens, a long narrow patio is ornamented with a water channel and two rows of water fountains (see Figure \(\PageIndex{68}\)). Generalife also contains a palace built in the same decorative manner as those within the Alhambra but its elaborate vegetable and ornamental gardens made this lush complex a welcome retreat for the rulers of Granada.

Interior and exterior re-imagined

To be sure, gardens and water fountains, canals, and pools are a recurring theme in construction across the Muslim dominion. Water is both practical and beautiful in architecture and in this respect the Alhambra and Generalife are no exception (see Figure \(\PageIndex{69}\)). But the Nasrid rulers of Granada made water integral. They brought the sound, sight and cooling qualities of water into close proximity, in gardens, courtyards, marble canals, and even directly indoors.

The Alhambra’s architecture shares many characteristics with other examples of Islamic architecture, but is singular in the way it complicates the relationship between interior and exterior. Its buildings feature shaded patios and covered walkways that pass from well-lit interior spaces onto shaded courtyards and sun-filled gardens all enlivened by the reflection of water and intricately carved stucco decoration.

More profoundly however, this is a place to reflect. Given the beauty, care and detail found at the Alhambra, it is tempting to imagine that the Nasrids planned to remain here forever; it is ironic then to see throughout the complex in the carved stucco, the words, “…no conqueror, but God” left by those that had once conquered Granada, and would themselves be conquered. It is a testament to the Alhambra that the Catholic monarchs who besieged and ultimately took the city left this complex largely intact.

The Victoria and Albert (V&A) Museum in London has an extensive collection of plasterwork from Granada—some of it original from the Alhambra, and some of it 19th century copies. In this video, Victor Borges, Senior Sculpture Conservator at the V&A, discusses the V&A collection and the new discoveries that have shed light on the the differences in materials and paint used in this sculptures, and what that tells us about why and how they were created and where they came from.

Victoria and Albert Museum, "Conservation: The Nasrid plasterwork collection at the V&A"

Dado Panel, Courtyard of the Royal Palace of Mas’ud III

by Elizabeth Kurtulik Mercuri

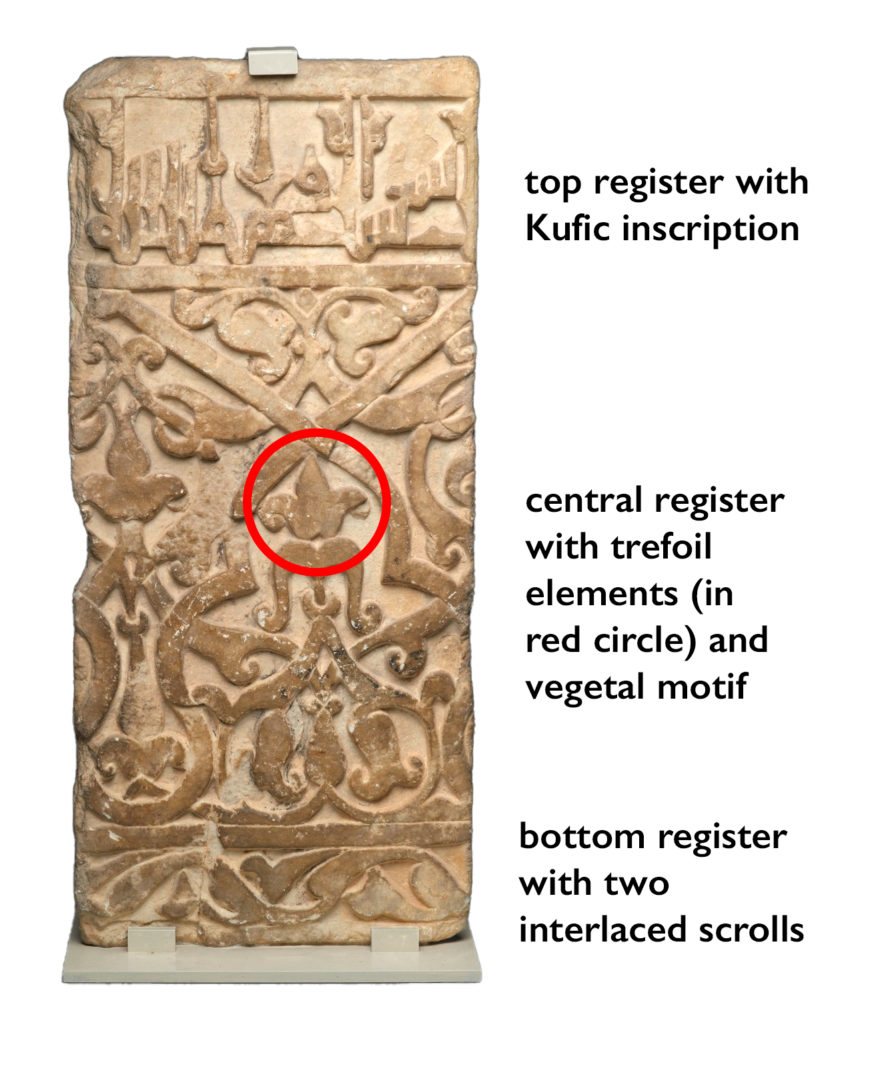

The dado panel from the Courtyard of the Royal Palace of Mas’ud III is a fine example of the artistic preferences of the Ghaznavid dynasty, which ruled the Indian subcontinent from 977 to 1186 (see Figure \(\PageIndex{70}\)). A dado panel is a two to three foot lower part of a wall, typically decorated in a variety of media. This dado panel formed part of a larger dado, found within the courtyard of the Palace of Mas’ud III, just south of Kabul, Afghanistan, and it is currently located in the Brooklyn Museum’s Arts of the Islamic World collection. Although the panel was not found in-situ, it closely resembles other panels found within the palace’s courtyard.

The panel can be broken up into three registers (see Figure \(\PageIndex{72}\)). The top register contains a Kufic inscription, which would have been part of a continuous inscription that encircled the entire courtyard across the tops of multiple adjacent panels. Kufic script is a style of writing Arabic popular from the seventh century CE until the late tenth century CE, as seen in the page from the Qur’an in Figure \(\PageIndex{71}\)). The central register of the dado panel is a large sequence of trefoil (tri-lobed leaf) elements with a vegetal motif, and the bottom register consists of two scrolls interlaced with each other. The panel would have been painted blue and red as well as gilded. It shows signs of wear, with markings and discoloration, most likely from exposure to various elements over time.

Uncovering a palace

The Ghaznavids were of Turkish origin, and they preferred a fusion of Iranian and Arab stylistic influences, along with a strong interest in Persian art and poetry. Their capital, Ghazni lay on an important trade route, resulting in influences from around the region. The Palace of Mas’ud III provides the best evidence for the social, cultural and artistic nature of the Ghaznavid Dynasty. The construction date is unknown but it was completed towards the end of the dynasty. It was built of a combination of baked and unbaked brick with pressed clay. It sits on a quadrangular plan organized around a central courtyard with four iwans.

The two excavations that were carried out between 1957 and 1966 produced a number of finds, including a long dado frieze in the courtyard. About forty-four panels were found in-situ and about four hundred dado fragments were also recovered. It is believed that there were about five hundred panels in all. They are made of marble, which came from a marble quarry found near Ghazni. The Ghaznavids used a large amount of marble throughout the city, during a time where brick and stucco were favored for décor purposes. The influence of the city of Baghdad, which was also built up heavily with marble by the Abbasids possibly explains the popularity of the medium at this time. Ghazni has only recently attracted scholars with the discovery of a great-stylized minaret, also dating to Mas’ud III’s reign (see Figure \(\PageIndex{73}\)).

Persian poetry

Although the Kufic inscription on this panel has not been translated, translations of other sections of the frieze contain a Persian poem that praised the Ghaznavid rulers. There is no author or written text to accompany the work, but scholars believe that the poet was someone associated with court life who probably wrote the poem for this specific purpose. This particular inscription, from the twelfth century, is one of the oldest uses of Persian in place of Arabic. It is likely that the inscription was commissioned in conjunction with the completion of the building, a practice that is also seen in Sicily and Alhambra. In Persia, it was common practice to adorn sacred and secular buildings with inscriptions (see the example from Iran, Figure \(\PageIndex{74}\))).

Part of a larger whole

The dado panel from the Brooklyn Museum is part of a much larger work of art and a representation of the very essence of the Ghaznavid Dynasty. It is evident that the Ghazavids were deviating from the artistic and architectural norms of the time with the construction of the palace dado frieze. Not only did they follow the Abbasids’ use of marble for decorative purposes, but they also used Persian within the dado inscription, which was unique at the time. The use of the inscription on the dado as a commemorative display to honor the leaders of the dynasty and mark the construction of the building was also unusual. The use of Persian terms in place of Arab letters might have been a result of their expanding empire, of the dynasty’s influential origins, or of an appreciation for Persian literature. The dado panel at the Brooklyn Museum is a rare work of art from a period of creative nonconformity, and it is representative of the Ghaznavids’ signature artistic style.

[Smarthistory] Editor’s note

The panel discussed above entered the Brooklyn Museum in 1986 as a gift. It was very likely excavated during a legal Italian-led archaeological campaign at Ghazni that began in the 1950s and that was abandoned when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979. While some well-documented objects from this excavation were exported with the permission of the Afghan Government, many thousands of works of art have been smuggled from this war-ravaged nation. It is imperative that museums investigate objects in their collections that were exported from source nations after the ratification of the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property and before the museum’s own internal controls were strengthened—objects such as this dado panel from the Courtyard of the Royal Palace of Mas’ud III. For more, see Matthieu Aikins’s article in The New York Times, “How One Looted Artifact Tells the Story of Modern Afghanistan” (March 8, 2021).

Gold pendant with inset enamel decoration

by The British Museum

This crescent-shaped gold pendant may originally have been hung with strings of pearls, from the three loops along the bottom (see Figure \(\PageIndex{75}\)). It is decorated with delicate bands of fine gold filigree around a small cloisonné enamel inset depicting two confronted birds and a central tree. The crescent shape is typical of jewelry produced in the Islamic world.

The Fatimid goldsmiths may have been inspired to use cloisonné enamel-work by imitating contemporary enameled gold jewelry from Byzantium. Such jewelry could have been imported, sent as diplomatic gifts from the Byzantine emperors, or made by Byzantine craftsmen who had moved to Fatimid Egypt. However, there is evidence that the Fatimid goldsmiths did not produce these enamel insets themselves, but rather bought them ready-made—perhaps as imports from Byzantium, or from Byzantine craftsmen living in Egypt.

The Fatimid dynasty was famous for its extraordinary treasury, stocked with riches and rarities from around the world. Some of these treasures were diplomatic gifts from other rulers, and included fine pieces of jewelry (see Figure \(\PageIndex{77}\)): in 1046, the Fatimid caliph received a huge gift from the Emperor of Byzantium, during the course of negotiations to renew an armistice between the two great powers. The gift was carried on the backs of two hundred mules wearing fine saddle-cloths, and included a hundred gold vessels with enamel inlay, as well as a thousand different types of fine brocade, gold-decorated girdles, and gold-embroidered turbans. Two hundred Muslim prisoners of war were also returned home. A contemporary Fatimid courtier recorded that “No former Byzantine emperor had ever offered a similar gift to any of the previous caliphs of Islam from time immemorial to the present time.”

The Great Mosque (or Masjid-e Jameh) of Isfahan

by Dr. Radha Dalal

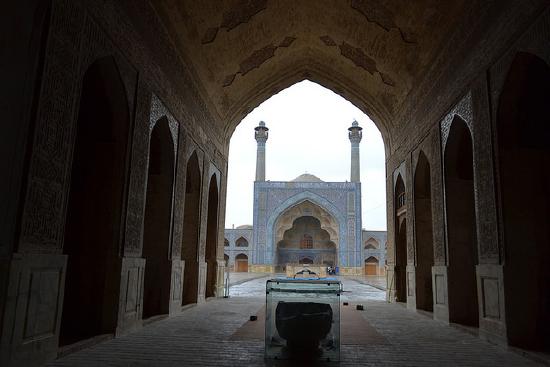

Most cities with sizable Muslim populations possess a primary congregational mosque. Diverse in design and dimensions, they can illustrate the style of the period or geographic region, the choices of the patron, and the expertise of the architect. Congregational mosques are often expanded in conjunction with the growth and needs of the umma, or Muslim community; however, it is uncommon for such expansion and modification to continue over a span of a thousand years. The Great Mosque of Isfahan in Iran is unique in this regard and thus enjoys a special place in the history of Islamic architecture (see Figure \(\PageIndex{78}\)). Its present configuration is the sum of building and decorating activities carried out from the 8th through the 20th centuries. It is an architectural documentary, visually embodying the political exigencies and aesthetic tastes of the great Islamic empires of Persia.

Another distinctive aspect of the mosque is its urban integration. Positioned at the center of the old city, the mosque shares walls with other buildings abutting its perimeter (see Figure \(\PageIndex{79}\)). Due to its immense size and its numerous entrances (all except one inaccessible now), it formed a pedestrian hub, connecting the arterial network of paths crisscrossing the city. Far from being an insular sacred monument, the mosque facilitated public mobility and commercial activity thus transcending its principal function as a place for prayer alone.

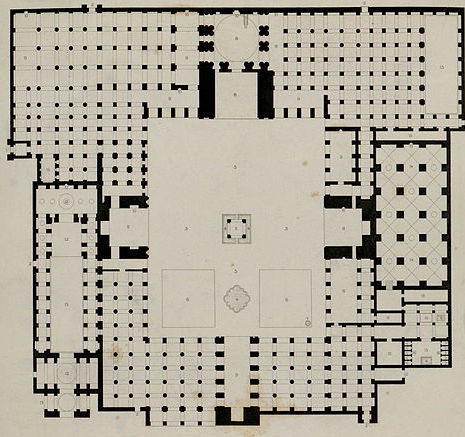

The mosque’s core structure dates primarily from the 11th century when the Seljuq Turks established Isfahan as their capital. Additions and alterations were made during Il-Khanid, Timurid, Safavid, and Qajar rule. An earlier mosque with a single inner courtyard already existed on the current location. Under the reign of Malik Shah I (ruled 1072-1092) and his immediate successors, the mosque grew to its current four-iwan design. Indeed, the Great Mosque of Isfahan is considered the prototype for future four-iwan mosques (an iwan is a vaulted space that opens on one side to a courtyard).

Linking the four iwans at the center is a large courtyard open to the air, which provides a tranquil space from the hustle and bustle of the city (see plan of the mosque in Figure \(\PageIndex{80}\)). Brick piers and columns support the roofing system and allow prayer halls to extend away from this central courtyard on each side. Aerial photographs of the building provide an interesting view; the mosque’s roof has the appearance of “bubble wrap” formed through the panoply of unusual but charming domes crowning its hypostyle interior.

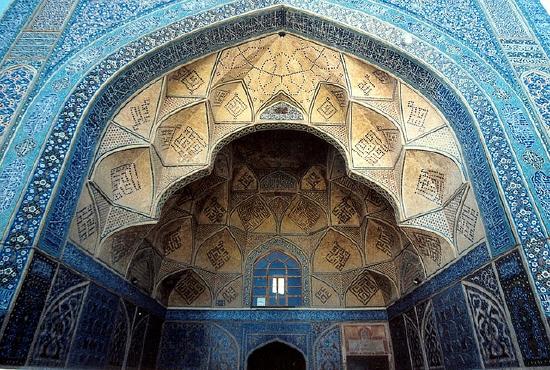

This simplicity of the earth-colored exterior belies the complexity of its internal decor. Dome soffits (undersides) are crafted in varied geometric designs and often include an oculus, a circular opening to the sky. Vaults, sometimes ribbed, offer lighting and ventilation to an otherwise dark space. Creative arrangement of bricks, intricate motifs in stucco, and sumptuous tile-work (later additions) harmonize the interior while simultaneously delighting the viewer at every turn. In this manner, movement within the mosque becomes a journey of discovery and a stroll across time.

Given its sprawling expanse, one can imagine how difficult it would be to locate the correct direction for prayer. The qibla iwan on the southern side of the courtyard solves this conundrum. It is the only one flanked by two cylindrical minarets and also serves as the entrance to one of two large, domed chambers within the mosque (see Figure \(\PageIndex{82}\)). Similar to its three counterparts, this iwan sports colorful tile decoration and muqarnas or traditional Islamic cusped niches (see Figure \(\PageIndex{83}\)). The domed interior was reserved for the use of the ruler and gives access to the main mihrab of the mosque.

The second domed room lies on a longitudinal axis right across the double-arcaded courtyard. This opposite placement and varied decoration underscores the political enmity between the respective patrons; each dome vies for primacy through its position and architectural articulation. Nizam al-Mulk, vizier to Malik Shah I, commissioned the qibla dome in 1086. But a year later, he fell out of favor with the ruler and Taj al-Mulk, his nemesis, with support from female members of the court, quickly replaced him. The new vizier’s dome (see Figure \(\PageIndex{84}\)), built in 1088, is smaller but considered a masterpiece of proportions.

When Shah Abbas I, a Safavid dynasty ruler, decided to move the capital of his empire from Qazvin to Isfahan in the late 16th century, he crafted a completely new imperial and mercantile center away from the old Seljuq city. While the new square and its adjoining buildings, renowned for their exquisite decorations, renewed Isfahan’s prestige among the early modern cities of the world, the significance of the Seljuq mosque and its influence on the population was not forgotten. This link amongst the political, commercial, social, and religious activities is nowhere more emphasized than in the architectural layout of Isfahan’s covered bazaar. Its massive brick vaulting and lengthy, sinuous route connects the Safavid center to the city’s ancient heart, the Great Mosque of Isfahan.

Two Royal Figures

by Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis and Dr. Steven Zucker

Transcript of a conversation between Dr. Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis and Dr. Steven Zucker

Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis: These are just perhaps my favorite figures in the entire Metropolitan Museum of Arts' Islamic Collection.

Steven Zucker: I don't think I've ever seen anything quite like these.

Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis: No, well, there really isn't anything else in the world like them. They are two exceptional pieces carved and molded sculptural figures made out of stucco. They are extraordinary.

Steven Zucker: Stucco. It's this soft, cement-like material, it's not stone, and so it's pretty easy to carve.

Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis: Oh, it's fantastic to carve. You can mold it and then carve it. The wonderful thing is it's light, it's easy to affix to walls.

Steven Zucker: Even though it's pretty soft stuff, it survived beautifully. These are in great condition.

Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis: They really are; probably one of the reasons why they're in such good condition is they were from the desert. I love them because they are so alive. They are so dynamic, beautiful, bright, gorgeous, and they also throw one of the great misconceptions about Islamic art out the window, which is that Islamic art is aniconic.

Steven Zucker: Right. I had been taught that in Islamic culture, just like in Judaic culture, you don't represent the human body, you don't represent animals.

Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis: That's true in a lot of cases, but that conception comes from one of the hadiths that says you basically shouldn't be making graven images, not too different from the prohibitions in the Old Testament; but, what seems to happen is very early on in Islamic art, that prohibition seems to be upheld in mosques, in religious spaces, but in the secular world, all bets are off.

Steven Zucker: This is a complex culture with subtle distinctions, and so making these kinds of broad generalizations really doesn't make sense.

Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis: That's exactly right. We have figurative works in stucco. We have it on ceramics, on vases, and metal work. We have it in manuscripts. We have it in painting. It's not like these are just one-offs, actually it's part of a much larger tradition, but these are just exceptional examples of it.

Steven Zucker: It's really all about context; so what do we think the context for these figures was?

Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis: That is one of the big questions. We don't know what the context is, but what we think is that they were probably in some type of reception hall and that they were affixed to the walls; so that when you were coming in to see a strong man or a new ruler, because these were produced around 1200, somewhere in Iran, which was a very unstable period, that these and perhaps others would greet you. Because we have other examples of painted reception rooms where we have guards or royal figures standing. We have examples in Bust in Afghanistan, and in Samarkand, as well, in Uzbekistan.

Steven Zucker: They're clearly representations of power. Both of them are clutching swords. They're armed and dangerous, but even a clear expression of their power, I think, comes from their dress.

Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis: Certainly, because, yes, we have the swords, we have this royal napkin that one of the figures is holding, but the dress is really impressive. This would have been blues, reds, black, and they would have been gilded as well. You have to imagine gold; they are bejeweled. They have earrings, they have necklaces.

Steven Zucker: I'm a little confused because you would think that these would be guards, but these are also royal figures.

Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis: That is the big question that we have. Are these princes? Kings of kings? Shahs of shahs. Or are they royal guards? They are wearing crowns. One of the figures here is wearing the winged crown. The winged crown in Iran is probably the oldest symbol of authority. It was worn by the Sasanian kings.

Steven Zucker: This is a pre-Islamic empire.

Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis: Yes, it was very, very powerful. To take this symbol of authority is really an amazing thing to do, because it is a symbol that is recognizable to almost anyone who walks into the room.