9.5: Late Classical and Hellenistic

- Page ID

- 108637

In 404 BCE, the formerly-mighty Athens lost the Peloponnesian War to their long-time rivals the Spartans, ending Athens’ status as the leading power in Greece. The city-states continued to battle amongst themselves until a larger, external threat forced them to band together for self-defense: King Philip II of Macedonia. Despite this unification, however, in 338 BCE the Greeks were soundly defeated at the Battle of Chaeronea—a battle joined by Philip’s 18-year old son Alexander, today more commonly known as Alexander the Great.

The political instability and strife, as well as the disillusionment of being conquered by a foreign power, are reflected in the art of the fourth century BCE. Whereas art of the High Classical period had tended to be serene and idealized, Late Classical art reflected a more human and individualized approach in its depiction of not just actual humans, like Lysippos’ Apoxyomenos (Scraper), but also heroes/demigods like Lysippos’ Weary Herakles and deities like Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos.

Apoxyomenos shows a young athlete in the very human act of cleaning himself, using a tool called a strigil to scrape away the oil he has applied, and with it dirt and sweat (see Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Compared to Polykleitos’ perfectly balanced and frontally-oriented Doryphoros, Lysippos’ Apoxyomenos not only shows a different canon of proportions--with a smaller head and slimmer build, but extends dynamically into space. For more on the sculpture, watch Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker discuss Apoxyomenos at the Vatican Museum (see Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos also shows a familiar, everyday act—although this time the subject preparing to step into her bath is the goddess of love and beauty (see Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). With her robe held lightly in her left hand and her right hand in front of her body in a gesture of modesty, Aphrodite’s stance shows the familiar contrapposto as well as an S-curve that characterized many of Praxiteles’ sculptures. Naked depictions of male figures were common, but before the Late Classical period, sculptures of women—and especially goddesses—were not naked. Aphrodite, with her nakedness, humanity, and sensuality, caused a sensation that is documented in many contemporary literary sources.

The humanized, non-idealized depiction of figures would reach its greatest extent in art of the Hellenistic period, which focused on emotion and drama, often intensified by compositions that were not balanced and perfected like High Classical sculpture, but that instead extended and even spiraled into space. As Greece became more cosmopolitan in the wake of Alexander the Great’s expansion of his empire, and came into contact with those from different places/cultures, the diversity in the people depicted would increase even more.

The Farnese Hercules: A Conversation

by Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

Weary from his labors, Hercules leans on his club, with hints of his heroic trials hidden in plain sight. This is the transcript of a conversation conducted at the Naples Archaeological Museum. Click to watch the video.

Dr. Zucker: We’re in Naples at the Archaeological Museum, looking at one of the most famous sculptures from all of antiquity.

Dr. Harris: It was discovered in the Renaissance during archaeological excavations in Rome of the Baths of Caracalla.

Dr. Zucker: This is the so-called Farnese Hercules and it gets that name because it was excavated by the Farnese family. They had been looking for building materials to take from ancient sites to build a new palace, but what they found in the Baths were an extraordinary array of ancient sculptures.

Dr. Harris: We can reconstruct the original site for this colossal sculpture. There were mosaic floors, walls made of different colored marble. It was an incredibly luxurious bathing complex, used by thousands of Romans every day and it was decorated with hundreds of sculptures, many of them colossal, like this one.

Dr. Zucker: These were really complex structures, these bathing facilities. There were the baths themselves. Some were cold, some were hot. There were rooms for transition from one temperature to another. There were places where one could exercise and this sculpture makes perfect sense in this environment. This is a place where you would go to work out, where you would go to exercise. You could look at this wildly muscular figure and have a bit of a goal.

Dr. Harris: Many of the sculptures that were found in the Baths of Caracalla were not the typical, ideal, athletic copies of Greek sculptures that we think of, but they were especially bulky, like the Hercules that we see here.

Dr. Zucker: We know that some successful Greek athletes would sometimes dedicate sculptures to Hercules in a way thanking him for their successes.

Dr. Harris: He was a symbol of strength and heroism.

Dr. Zucker: You can see that here, but there’s also irony in Lysippos’ treatment, because even as we see this wildly powerful figure, this incredible musculature, we also see a figure that is exhausted.

Dr. Harris: He really is. He leans almost his full weight on a club that’s propped up under his arm, so you’re right, there is an irony between the brute strength of his articulated muscles and the languorousness of his pose.

Dr. Zucker: Look at the way in which that abdomen is articulated. Look at the strength of his right shoulder, of his right upper arm. It’s really massive.

Dr. Harris: He thrusts his right hip out, so that he can fully lean his weight on his left side.

Dr. Zucker: There is this marvelous contrapposto, although the legs seem to be somewhat reversed, but I love the way his torso slouches over as he leans and there’s this overemphasized turn of that torso.

Dr. Harris: But the club doesn’t look like a very secure support.

Dr. Zucker: No, the whole thing is slightly precarious.

Dr. Harris: It seems as if Lysippos and Glycon, who copied Lysippos’ sculpture and there are more than 80 copies of sculptures of the weary Hercules that have survived, but it does seem as though he’s calling our attention to Hercules’ hands and Hercules is famous as a hero who became a god and who these amazing exploits, the 12 labors of Hercules. I’m noticing the open left hand and the way that the right hand is brought behind his back, so we really want to move around the sculpture to see what’s in his right hand.

Dr. Zucker: That’s right. The artist has set us up so that we absolutely want to walk around. The left hand is not original, that’s been lost. So what we’re seeing is a plaster reconstruction, but the right hand is original and if you walk around the sculpture, you actually see that he’s holding the apples that he would have gotten from one of those labors, the labor the apples of the Hesperides. This is all part of the legend of Heracles. Heracles was the original Greek figure and the Romans would call him Hercules. What happened was this brute of a man, in a fit, killed his children. The gods of Mount Olympus punished him by putting this man, Heracles, who was the son of a god and of a human, therefore a hero. They made him subservient to a king and he had to perform whatever deeds this king asked of him for 12 years. This was his punishment. The king asked of him tremendously difficult tasks. The first of which was the killing of the Nemean lion. If you look carefully, just draped over the club, you can see the pelt of that lion that he had slayed. This sculpture is actually referring to two of those labors.

Dr. Harris: One of the things that seems a little strange as we look up at him is how small his head is. This is something that Lysippos, the Greek sculptor–

Dr. Zucker: The original sculptor–

Dr. Harris: That this was based on, was known for, was changing the cannon of proportions that existed during the Classical period in Greece in the fifth century where there was more of a sense of harmony and balance between the parts of the body. Lysippos created a new set of proportions, where the figure was taller, the head was smaller, and they gave the figure a new sense of elegance.

Dr. Zucker: Elegance and also height. Here, it’s married, of course, with this increased bulk. The other thing that Lysippos is so well known for, which you mentioned earlier, is the way in which he begins to break out of the more restricted space that Classical figures had generally occupied, so that by extending, for instance, that left hand, by moving that right hand behind his back, he really does invite us to understand this sculpture in the round, as opposed to seeing it as a frontal object. The thing that strikes me most, though, about this sculpture, is the way in which we can understand his feeling of exhaustion and the way that’s contrasted against the potential energy and power of that body.

Dr. Harris: The things that we’re talking about, the new cannon of proportions, the way that we’re asked to move around the sculpture, not only do I want to walk behind it to see what’s in his right hand, but I also want to walk to the place where he is looking down to, so we can look up at his face and see the expression, the sense of empathy we have for him. These are all things that are typical of the Hellenistic period of ancient Greek art that this copy was based on.

Dr. Zucker: Clearly, something that the Romans really appreciated.

Dr. Harris refers to this sculpture as being from the Hellenistic period, but most art historians consider it to be Late Classical.

Hellenistic Sculpture

By Boundless Art History

Altar of Zeus

The great Altar of Zeus, now housed in Germany, was commissioned in the first half of the second century BCE during the reign of King Eumenes II to commemorate his victory over the Gauls, who were migrating into Asia Minor.

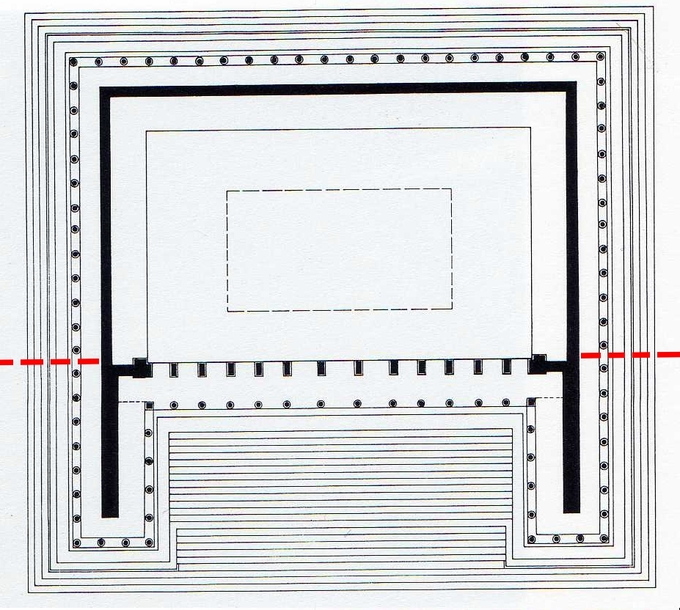

The altar is a U-shaped Ionic building built on a high platform with central steps leading to the top (see Figures \(\PageIndex{6}\) and \(\PageIndex{7}\)). It faced east, was located near the theater of Pergamon, and commanded an outstanding view of the region. The altar is known for its grand design and for its frieze depicting the Gigantomachy—it wraps 370 feet around the base of the altar.

The Gigantomachy

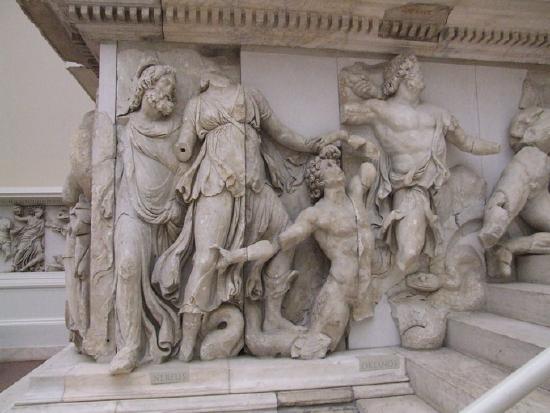

The Gigantomachy depicts the Olympian gods fighting against their predecessors the Giants (Titans), the children of the goddess Gaia (see Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). The frieze is known for its incredibly high relief, in which the figures are barely restrained by the wall, and for its deep drilling of lines with details to create dramatic shadows.

The high relief and deep drilling of the figures also increases the liveliness and naturalism of the scene. The figures are rendered with high plasticity. The texture of their skin, drapery, and scales add another level of naturalism. Furthermore, as the frieze follows the stairs, the limbs of the figures begin to spill out of their frame and onto the stairs, physically breaking into the space of the viewer . The style and high drama of the scenes is often referred to as the Hellenistic Baroque for its exaggerated motion, emphasis on details, and the liveliness of the characters.

The most famous scene on the frieze depicts Athena fighting the giant Alkyoneus (see Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). She grabs his head and pulls it back while Gaia emerges from the ground to plead for her son’s life and a winged Nike reaches over to crown Athena.

Athena’s drapery swirls around her with deep folds and her whole body is nearly removed from the frieze. The figures are depicted with the heightened emotion commonly found on Hellenistic statues. Alkyoneus’s face strains in pain and Gaia’s eyes, which are all that remain of her face, are full of terror and sorrow at the death of her son.

The entire composition is depicted in a chiastic shape. Athena stretches out to grasps Alkoyneus’s head, the two figures pull at each other in opposite directions. Meanwhile, the figure of Nike moves diagonally towards Athena, showing their convergence in a moment of victory. The diagonal line created by Gaia mimics the shape of her son, connecting the two figures through line and pathos. The scene is filled with the tension and emotion that are key features in Hellenistic sculpture.

The Dying Gauls

A group of statues depicting dying Gauls, the defeated enemies of the Attalids, were situated inside the Altar of Zeus (see Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). The original set of statues is believed to have been cast in bronze by the court sculptor Epigonus in 230-220 BCE. Now only marble Roman copies of the figures remain.

Like the figures on the frieze and other Hellenistic sculptures, the figures are depicted with lifelike details and a high level of naturalism. They are also depicted in the common motif of barbarians. The men are nude and wear Celtic torcs [necklaces indicating status]. Their hair is shaggy and disheveled. The figures are positioned in dramatic compositions and are shown dying heroically, which turns them into worthy adversaries, increasing the perception of power of the Attalid dynasty. All three figures in the group are depicted in a Hellenistic manner. To fully appreciate the statues, it is best to walk around them. Their pain, nobility, and death are evident from all angles.

One Gaul is depicted lying down, supporting himself over his shield and a discarded trumpet. He furrows his brow as he looks downward at his bleeding chest wound as he prepares himself for death. His muscles are large and strong, signifying his strength as a warrior and implying the strength of the one who struck him down.

Two other figures complete the group. One figure depicts a Gallic chief committing suicide after he has killed his own wife (see Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\)). Also known as the Ludovisi Gaul, this sculpture group displays another heroic and noble deed of the foes, for typically women and children of the defeated would be murdered to avoid them from being captured and sold as slaves by the victors. The chief holds his fallen wife by the arm as he plunges his sword into his chest, where blood is already exiting the wound. [See the earlier Editors' Note about Sexual Violence in Greek Art for a refresher about such violent depictions.]

Hellenistic sculpture continues the trend of increasing naturalism seen in the stylistic development of Greek art. During this time, the rules of Classical art were pushed and abandoned in favor of new themes, genres, drama, and pathos that were never explored by previous Greek artists.

Furthermore, the Greek artists added a new level of naturalism to their figures by adding an elasticity to their form and expressions, both facial and physical. These figures interact with their audience in a new theatrical manner by eliciting an emotional reaction from their view—this is known as pathos.

Nike of Samothrace

One of the most iconic statues of the period, the Nike of Samothrace, also known as the Winged Victory, c. 190 BCE, commemorates a naval victory (see Figure \(\PageIndex{12}\)). This Parian marble statue depicts Nike, now armless and headless, alighting onto the prow of the ship. The prow is visible beneath her feet, and the scene is filled with theatricality and naturalism as the statue reacts to her surroundings.

Nike’s feet, legs, and body thrust forward in contradiction to her drapery and wings that stream backwards. Her clothing whips around her from the wind and her wings lift upwards. This depiction provides the impression that she has just landed and that this is the precise moment that she is settling onto the ship’s prow.

In addition to the sculpting, the figure was most likely set within a fountain, creating a theatrical setting where both the imagery and the auditory effect of the fountain would create a striking image of action and triumph.

Venus de Milo

Also known as the Aphrodite of Melos (c. 150-125 BCE), this sculpture by Alexandros of Antioch, is another well-known icon of the Hellenistic period (see Figure \(\PageIndex{13}\)). Today the goddess’s arms are missing. It has been suggested that one arm clutched at her slipping drapery while the other arm held out an apple, an allusion to the Judgment of Paris and the abduction of Helen.

Originally, like all Greek sculptures, the statue would have been painted and adorned with metal jewelry, which is evident from the attachment holes. This image is in some ways similar to Praxiteles’ Late Classical sculpture Aphrodite of Knidos (fourth century BCE), but it is considered to be more erotic than its earlier counterpart.

For instance, while she is covered below the waist, Aphrodite makes little attempt to cover herself. She appears to be teasing and ignoring her viewer, instead of accosting him and making eye contact.

Altered States

While the Nike of Samothrace exudes a sense of drama and the Venus de Milo a new level of feminine sexuality, other Greek sculptors explored new states of being. Instead of reproducing images of the ideal Greek male or female, as was favored during the Classical period, sculptors began to depict images of the old, tired, sleeping, and drunk—none of which are ideal representations of a man or woman.

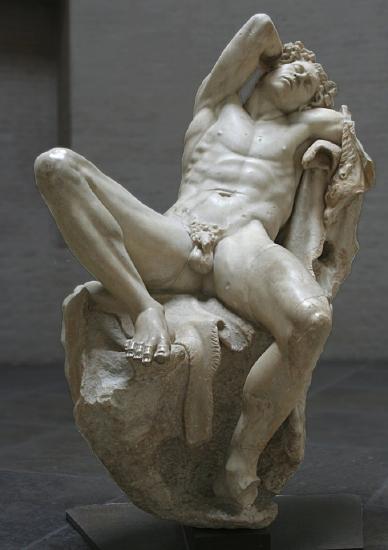

The Barberini Faun

The Barberini Faun, also known as the Sleeping Satyr (c. 220 BCE), depicts an effeminate figure, most likely a satyr, drunk and passed out on a rock. His body splays across the rock face without regard to modesty (see Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\)).

He appears to have fallen to sleep in the midst of a drunken revelry and he sleeps restlessly, his brow is knotted, face worried, and his limbs are tense and stiff. Unlike earlier depicts of nude men, but in a similar manner to the Venus de Milo, the Barberini Faun seems to exude sexuality.

Drunken Old Woman

Images of drunkenness were also created of women, which can be seen in a statue attributed to the Hellenistic artist Myron of a drunken beggar woman (see Figure \(\PageIndex{15}\)). This woman sits on the floor with her arms and legs wrapped around a large jug and a hand gripping the jug’s neck.

Grape vines decorating the top of the jug make it clear that it holds wine. The woman’s face, instead of being expressionless, is turned upward and she appears to be calling out, possibly to passersby. Not only is she intoxicated, but she is old: deep wrinkles line her face, her eyes are sunken, and her bones stick out through her skin.

Seated Boxer

Another image of the old and weary is a bronze statue of a seated boxer (see Figure \(\PageIndex{16}\)). While the image of an athlete is a common theme in Greek art, this bronze presents a Hellenistic twist.

He is old and tired, much like the Late Classical image of a Weary Herakles. However, unlike Herakles, the boxer is depicted beaten and exhausted from his pursuit. His face is swollen, lip spilt, and ears cauliflowered. This is not an image of a heroic, young athlete but rather an old, defeated man many years past his prime.

Portraiture

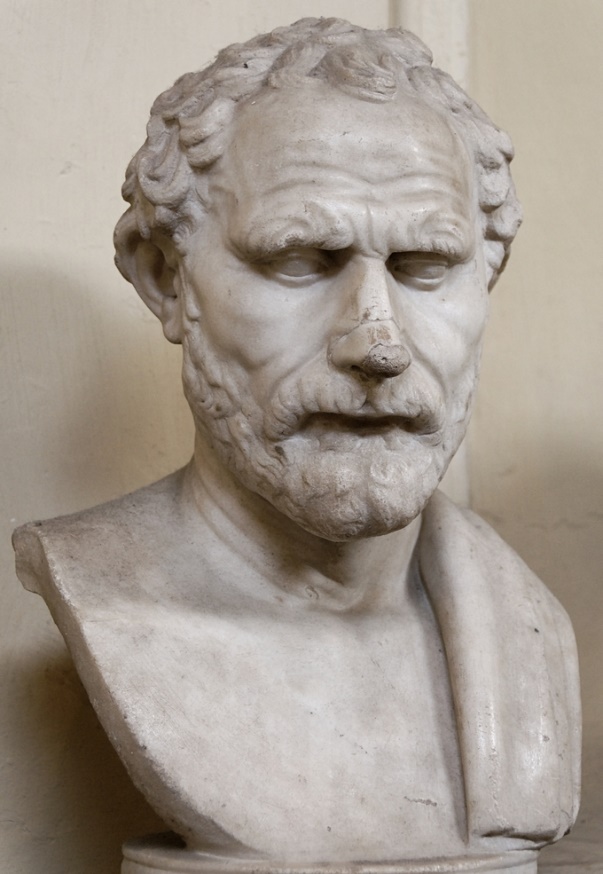

Individual portraits, instead of idealization, also became popular during the Hellenistic period. A portrait of Demosthenes by Polyeuktos, 280 BCE, is not an idealization of the Athenian statesman and orator (see Figure \(\PageIndex{17}\)). Instead, the statue takes notes of Demosthenes’s characteristic features, including his overbite, furrowed brow, stooped shoulders, and old, loose skin.

Even portrait busts, often copied from Polyeuktos’ famed statue, depict the weariness and sorrow of a man despairing the conquest of Philip II and end of Athenian democracy.

Roman Patronage

The Greek peninsula fell to Roman power in 146 BCE. Greece was a key province of the Roman Empire, and the Roman’s interest in Greek culture helped to circulate Greek art around the empire, especially in Italy, during the Hellenistic period and into the Imperial period of Roman hegemony.

Greek sculptors were in high demand throughout the remaining territories of the Alexander’s empire and then throughout the Roman Empire. Famous Greek statues were copied and replicated for wealthy Roman patricians and Greek artists were commissioned for large-scale sculptures in the Hellenistic style.

Originally cast in bronze, many Greek sculptures that we have today survive only as marble Roman copies. Some of the most famous colossal marble groups were sculpted in the Hellenistic style for wealthy Roman patrons and for the imperial court. Despite their Roman audience, these were purposely created in the Greek style and continued to display the drama, tension, and pathos of Hellenistic art.

Laocoön and His Sons

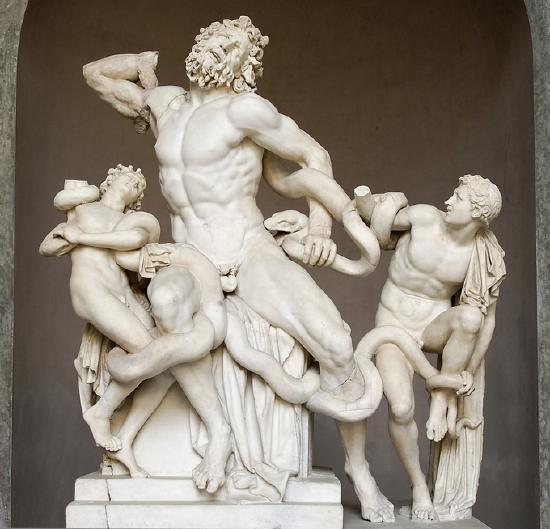

Laocoön was a Trojan priest of Poseidon who warned the Trojans, “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts,” when the Greeks left a large wooden horse at the gates of Troy. Athena or Poseidon (depending on the story’s version), upset by his vain warning to his people, sent two sea serpents to torture and kill the priest and his two sons.

Similar to other examples of Hellenistic sculpture, Laocoön and His Sons depicts a chiastic scene filled with drama, tension, and pathos (see Figures \(\PageIndex{18}\) and \(\PageIndex{29}\)). The figures writhe as they are caught in the coils of the serpents. The faces of the three men are filled with agony and toil, which is reflected in the tension and strain of their muscles. Laocoön stretches out in a long diagonal from his right arm to his left as he attempts to free himself.His sons are also entangled by the serpents, and their faces react to their doom with confusion and despair. The carving and detail, the attention to the musculature of the body, and the deep drilling, seen in Laocoön’s hair and beard, are all characteristic elements of the Hellenistic style.

Farnese Bull

The Farnese Bull (c. 200–180 BCE), named for the patrician Roman family who owned the statue in the Italian Renaissance, is believed to have been created for the collection of Asinius Pollio, a Roman patrician (see Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\)). Pliny the Elder attributes the statue to the artists and brothers Apolllonius and Tauriscus of Trallles, Rhodes.The colossal marble statue, carved from a single block of marble, depicts the myth of Dirce, the wife of the King of Thebes, who was tied to a bull by the sons of Antiope to punish her for mistreating their mother. The composition is large and dramatic, and demands the viewer to encircle it in order to view and appreciate the narrative and pathos from all angles. The various angles reveal different expressions, from the terror of Dirce, to the determination of Antiope’s sons, to the savagery of the bull.

Sculptural Buddhas made in the Gandharan region (located in the area between present-day Pakistan and Afghanistan) in the Kushan dynasty are often described as having a “Greco-Roman” or “Greco-Buddhist” aesthetic. As compared to the Buddhas produced during the same time in Mathura (a northern Indian city), they are less stylized, with more naturalistic facial features, proportions, and drapery (see Figure \(\PageIndex{21}\)). The European scholars who applied the Greco-Buddhist label to the Gandharan Buddhas believed that this hybrid style was the result of a cultural syncretism between Classical Greek and Buddhist cultures, which came into close contact during the thousand years following Alexander the Great’s 4th century conquests.

Gandhara itself was positioned, as the British Museum puts it, “at the ‘crossroads of Asia,’” and “has always been an ancient transit zone,” one “certainly well known to the Greeks in the fifth century BCE.” They continue, “As a result of the various cultures that either settled or moved along these trade routes, [Gandharan] sculptures have taken on a distinctive style, combining Graeco-Roman, Indian, Chinese, and Central Asian influences.” This hybrid style is evident in the graceful and elegant Gandharan Head of the Buddha, which pairs stylized, almost geometric eyebrows and hair with a more naturalistic nose, mouth, and the distinctive inward-gazing, heavy-lidded eyes.

Other scholars, however, have contested the “Greco-Buddhist” label, arguing for a more nuanced understanding of, and approach to, the style. In his paper for Journal of Art Historiography, Michael Falser interrogates the construction of the term “Graeco-Buddhist Style of Gandhara.” Put simply, Falser would like the Gandharan style to be understood by and studied for its own merits. He argues that conceiving of this style as a Eurasian hybrid, rather than its own unique style, stems from a problematic art historical trend of assigning essentializing labels such as “Classical Greek” or “Buddhist.” Instead of considering the Gandharan artists as being influenced by Classical ones, Falser champions a “nationalist appropriation” of the style. He encourages art historians to consider decolonial approaches to understanding the Gandharan aesthetics and artistic innovation as a distinct and “valid cultural heritage of the nation states of Pakistan and Afghanistan.”

Article in this section:

- Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, "Lysippos, Farnese Hercules," in Smarthistory, December 9, 2015 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Boundless Art History, “The Hellenistic Period.” (CC BY SA)