8.3: Mycenaean

- Page ID

- 108617

Mycenaean Art & Architecture

By Boundless Art History

Mycenaean Architecture

Mycenaean culture can be summarized by its architecture, whose remains demonstrate the Mycenaeans’ war-like culture and the dominance of citadel sites ruled by a single ruler. The Mycenaeans populated Greece and built citadels on high, rocky outcroppings that provided natural fortification and overlooked the plains used for farming and raising livestock. The citadels vary from city to city but each share common attributes, including building techniques and architectural features.

Building Techniques

The walls of Mycenaean citadel sites were often built with ashlar and massive stone blocks. The blocks were considered too large to be moved by humans and were believed by ancient Greeks to have been erected by the Cyclopes—one-eyed giants. Due to this ancient belief, the use of large, roughly cut, ashlar blocks in building is referred to as Cyclopean masonry. The thick Cyclopean walls reflect a need for protection and self-defense since these walls often encircled the citadel site and the acropolis on which the site was located.

Corbel Arch

The Mycenaeans also relied on new techniques of building to create supportive archways and vaults. A typical post and lintel structure is not strong enough to support the heavy structures built above it. Therefore, a corbeled (or corbel) arch is employed over doorways to relieve the weight on the lintel.

The corbel arch is constructed by offsetting successive courses of stone (or brick) at the springline of the walls so that they project towards the archway’s center from each supporting side, until the courses meet at the apex of the archway (often, the last gap is bridged with a flat stone). The corbel arch was often used by the Mycenaeans in conjunction with a relieving triangle, which was a triangular block of stone that fit into the recess of the corbeled arch and helped to redistribute weight from the lintel to the supporting walls.

Citadel Sites

Mycenaean citadel sites were centered around the megaron, a reception area for the king. The megaron was a rectangular hall, fronted by an open, two-columned porch. It contained a more or less central open hearth, which was vented though an oculus in the roof above it and surrounded by four columns. The architectural plan of the megaron became the basic shape of Greek temples, demonstrating the cultural shift as the gods of ancient Greece took the place of the Mycenaean rulers.

Citadel sites were protected from invasion through natural and man-made fortification. In addition to thick walls, the sites were protected by controlled access. Entrance to the site was through one or two large gates, and the pathway into the main part of the citadel was often controlled by more gates or narrow passageways. Since citadels had to protect the area’s people in times of warfare, the sites were equipped for sieges. Deep water wells, storage rooms, and open space for livestock and additional citizens allowed a city to access basic needs while being protected during times of war.

Mycenae

The citadel site of Mycenae was the center of Mycenaean culture. It overlooks the Argos plain on the Peloponnesian peninsula, and according to Greek mythology was the home to King Agamemnon.

The site’s megaron sits on the highest part of the acropolis and is reached through a large staircase. Inside the walls are various rooms for administration and storage along with palace quarters, living spaces, and temples. A large grave site, known as Grave Circle A, is also built within the walls.

The main approach to the citadel is through the Lion Gate, a Cyclopean-walled entrance way. The gate is 20 feet wide, which is large enough for citizens and wagons to pass through, but its size and the walls on either side create a tunneling effect that makes it difficult for an invading army to penetrate.

The gate is famous for its use of the relieving arch, a corbeled arch that leaves an opening and lightens the weight carried by the lintel. The Lion Gate received its name from its decorated relieving triangle of lions one either side of a single column. This composition of lions or another feline animal flanking a single object is known as a heraldic composition. The lions represent cultural influences from the Ancient Near East. Their heads are turned to face outwards and confront those who enter the gate.

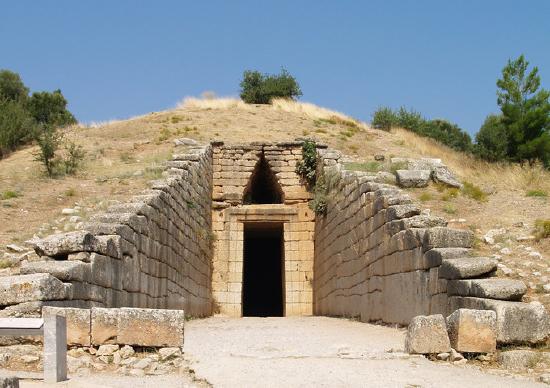

Mycenae is also home to a subterranean beehive-shaped tomb (also known as a tholos tomb) that was located outside the citadel walls. The tomb is known today as the Treasury of Atreus (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)), due to the wealth of grave goods found there.

This tomb and others like it are demonstrations of corbeled vaulting that covers an expansive open space. The vault is 44 feet high and 48 feet in diameter. The tombs are entered through a narrow passageway known as a dromos and a post-and-lintel doorway topped by a relieving triangle.

Tiyrns

The citadel site of Tiryns, another example of Mycenaean fortification, was a hill fort that has been occupied over the course of 7000 years. It reached its height between 1400 and 1200 BCE, when it was one of the most important centers of the Mycenaean world. Its most notable features were its palace, its Cyclopean tunnels, its walls, and its tightly controlled access to the megaron (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)) and main rooms of the citadel.

Just a few gates provide access to the hill but only one path leads to the main site. This path is narrow and protected by a series of gates that could be opened and closed to trap invaders. The central megaron is easy to locate, and it is surrounded by various palatial and administrative rooms. The megaron is accessed through a courtyard that is decorated on three sides with a colonnade.

The famous megaron has a large reception hall, the main room of which had a throne placed against the right wall and a central hearth bordered by four wooden columns that served as supports for the roof. It was laid out around a circular hearth surrounded by four columns. Although individual citadel sites varied to a degree, their overall uniformity allows us to compare design elements easily. For example, the hearth of the megaron at the citadel of Pylos provides an idea of how its counterpart at Tiryns appears.

Mycenaean Metallurgy

The Mycenaeans were masterful metalworkers, as their gold, silver, and bronze daggers, drinking cups, and other objects demonstrate.

Grave Circle A at Mycenae

Grave Circle A is a set of graves from the sixteenth century BCE located at Mycenae. The grave circle was originally located outside the walls of the city but was later encompassed inside the walls of the citadel when the city’s walls were enlarged during the thirteenth century BCE. The grave circle is surrounded by a second wall and only has one entrance. Inside are six tombs for nineteen bodies that were buried inside shaft graves. The shaft graves were deep, narrow shafts dug into the ground. The body would be placed inside a stone coffin and placed at the bottom of the grave along with grave goods. The graves were often marked by a mound of earth above them and grave stele.

The grave site was excavated by Heinrich Schliemann in 1876, who excavated ancient sites such as Mycenae and Troy based on the writings of Homer and was determined to find archaeological remains that aligned with observations discussed in the Iliad and the Odyssey. The archaeological methods of the nineteenth century were different than those of the twenty-first century and Schliemann’s desire to discover remains that aligned with mythologies and Homeric stories did not seem as unusual as it does today. Upon excavating the tombs, Schliemann declared that he found the remains of Agamemnon and many of his followers.

Grave Circle B

An additional grave circle, Grave Circle B, is also located at Mycenae, although this one was never incorporated into the citadel site. The two grave circles were elite burial grounds for the ruling dynasty. The graves were filled with precious items made from expensive material, including gold, silver, and bronze.

The amount of gold, silver, and previous materials in these tombs not only depict the wealth of the ruling class of the Mycenae but also demonstrates the talent and artistry of Mycenaean metalworking. Reoccurring themes and motifs underline the culture’s propensity for war and the cross-cultural connections that the Mycenaeans established with other Mediterranean cultures through trade, including the Minoans, Egyptians, and even the Orientalizing style of the Ancient Near East

Gold Death Masks

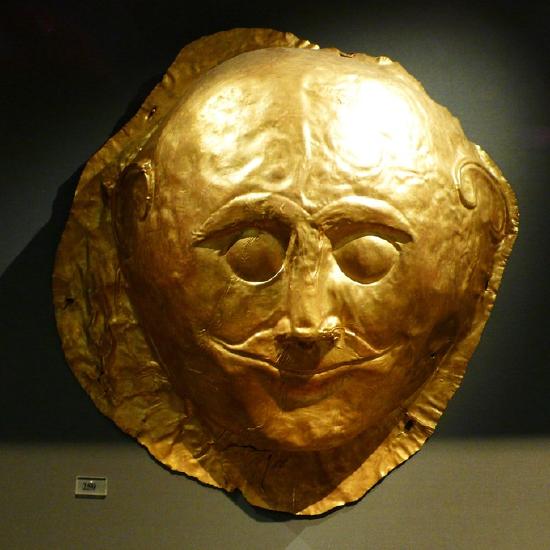

Repoussé death masks were found in many of the tombs. The death masks were created from thin sheets of gold, through a careful method of metalworking to create a low relief.

These objects are fragile, carefully crafted, and laid over the face of the dead. Schliemann called the most famous of the death masks the Mask of Agamemnon, under the assumption that this was the burial site of the Homeric king. The mask depicts a man with a triangular face, bushy eyebrows, a narrow nose, pursed lips, a mustache, and stylized ears.

This mask is an impressive and beautiful specimen but looks quite different from other death masks found at the site. The faces on other death masks (such as in Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)) are rounder; the eyes are more bulbous; and at least one bears a hint of a smile. None of the other figures has a mustache or even the hint of beard.

In fact, the mustache looks distinctly nineteenth century and is comparable to the mustache that Schliemann himself had. The artistic quality between the Mask of Agamemnon and the others seems dramatically different. Despite these differences, the Mask of Agamemnon has inserted itself into the story of Mycenaean art.

Bronze Daggers

Decorative bronze daggers found in the grave shafts suggest there were multicultural influences on Mycenaean artists. These ceremonial daggers were made of bronze and inlaid in silver, gold, and niello with scenes that were clearly influenced from foreign cultures.

Two daggers that were excavated depict scenes of hunts, which suggest an Ancient Near East influence. One of these scenes depicts lions hunting prey, while the other scene depicts a lion hunt (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)). The portrayal of the figures in the lion hunt scene draws distinctly from the style of figures found in Minoan painting. These figures have narrow waists, broad shoulders, and large, muscular thighs.

The scene between the hunters and the lions is dramatic and full of energy, another Minoan influence. Another dagger depicts the influence of Minoan painting and imagery through the depiction of marine life, and Egyptian influences are seen on a dagger filled with lotus and papyrus reeds along with fowl.

Gold and Silver Drinking Cups

A variety of gold and silver drinking cups have also been found in these grave shafts. These include a rhyton in the shape of a bull’s head, with golden horns and a decorative, stylized gold flower, made from silver repoussé (Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). Other cups include the golden Cup of Nestor (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)), a large two-handle cup that Schliemann attributed to the legendary Mycenaean hero Nestor, a Trojan War veteran who plays a peripheral role in The Odyssey.

A silver rhyton called the Silver Siege Rhyton was likely used for ritual libations. The Silver Siege Rhyton is unique for its depiction of a siege. The scene is only preserved on a portion of the rhyton, but a landscape of trees and a fortress wall are clearly recognizable. The figures in the scene appear to be in various positions, some men fight each other. An archer crouches with his bow and arrow, while others throw rocks down from the wall at the invaders.

Mycenaean Ceramics

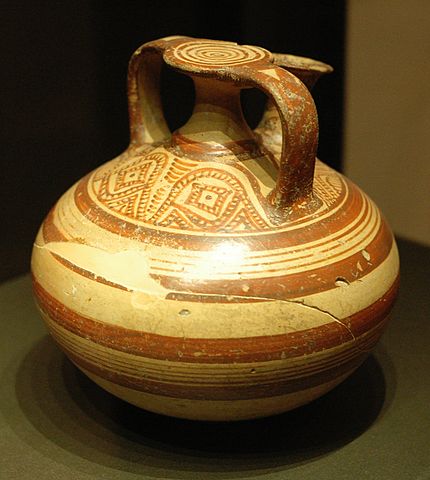

The Mycenaeans created numerous ceramic vessels of various types and decorated them in a variety of styles. These vessels were popular outside of Greece, and were often exported and traded around the Mediterranean and have been found in Egypt, Italy, Asia Minor, and Spain.

Two of the main production centers were the Mycenaean cities at Athens and Corinth. The products of the two centers were distinguishable by their color and decoration. Corinthian clay was a pale yellow and tended to feature painted scenes based on nature, while the Athenian potters decorated their vessels with a rich red and preferred geometric designs.

Vessels

The most popular types of vessels included kraters—large, open-mouth jars to mix wine and water—pitchers, and stirrup jars, which are so named for the handles that came above the top of the vessel. Mycenaean vessels usually had a pale, off-white background and were painted in a single color, either red, brown, or black.

Popular motifs include abstract geometric designs, animals, marine life, or narrative scenes. The presence of nature scenes, especially of marine life and of bulls, seems to suggest a Minoan influence on the style and motifs painted on the Mycenaean pots.

Vessels served the purposes of storage, processing, and transfer. There are a few different classes of pottery, generally separated into two main sections: utilitarian and elite.

- Utilitarian pottery is sometimes decorated, made for functional domestic use, and constitutes the bulk of the pottery made.

- Elite pottery is finely made and elaborately decorated with great regard for detail. This form of pottery is generally made for holding precious liquids and for decoration.

Stirrup Jars

Stirrup jars, mainly used for storing liquids such as oil and wine, could have been economically valuable in Mycenaean households. The arrangement of common features suggests that a stopper is used to secure the contents and the contents are what make the jar a valuable household item.

The disc holes and third handle may have been used to secure a tag to the vessel, suggesting it had commercial importance and resale value. The locations where stirrup jars have been found reflect the fact that the popularity of this vessel type spread quickly throughout the Aegean, and the use of the stirrup jar to identify a specific commodity became important.

Warrior Vase

The Warrior Vase (c. 1200 BCE) is a bell krater that depicts a woman bidding farewell to a group of warriors. The scene is simple and lacks a background.

The men all carry round shields and spears and wear helmets. Attached to their spears are knapsacks, which suggest that they must travel long distances to battle. On one side, the soldiers wear helmets ornamented with horns. The soldiers on the other side wear hedgehog-style helmets. A single woman stands to the left with her arm raised and a group of identically dressed and heavily armed men is marching off to the right.

There is no way to tell which woman is waving goodbye, as all the figures are generic and none specifically interacts with her, nor do they interact with each other. The figures are stocky and lack the sinuous lines of the painted Minoan figures.

Furthermore, while the men all face right with wide stances and appear to move in that direction, their flat feet and twisted perspective bodies inhibit any potential for movement. Instead the figures remain static and upright. The imagery depicts a simple narrative that in the warrior culture of the Mycenaeans must have often been reenacted.

Many scholars observe that the style of the figures and the handles of this thirteenth century BCE vase are very similar to eighth century BCE pottery. Similar spearmen are also depicted in eighth century BCE pottery which introduces a curious 500 year gap in styles.

Other sculpture

There are few examples of large-scale, freestanding sculptures from the Mycenaeans. A painted plaster head of a female—perhaps depicting a priestess, goddess, or sphinx —is one of the few examples of large-scale sculpture.

The head is painted white, suggesting that it depicts a female. A red band wraps around her head with bits of hair underneath. The eyes and eyebrows are outlined in blue, the lips are red, and red circles surrounded by small red dots are on her checks and chin.

Articles in this section:

- Lumen Learning, "Mycenaean Art," in Boundless Art History (CC BY-SA 2.0)