6.5: Persia

- Page ID

- 108579

Ancient Persia, an introduction

by Senta German

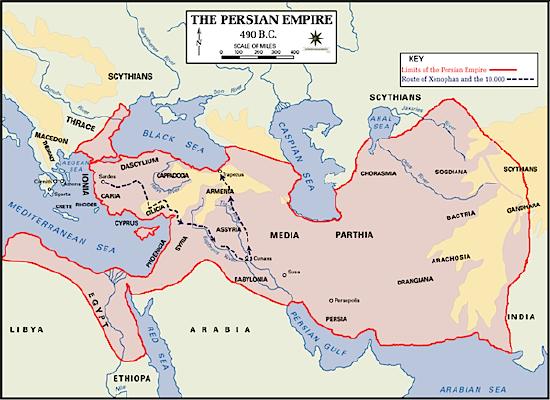

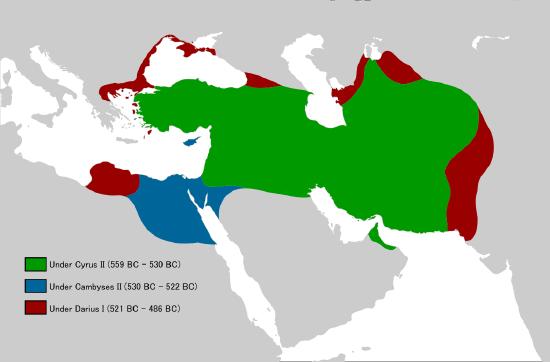

The heart of ancient Persia is in what is now southwest Iran, in the region called the Fars. In the second half of the 6th century BCE, the Persians (also called the Achaemenids) created an enormous empire reaching from the Indus Valley to Northern Greece and from Central Asia to Egypt.

A tolerant empire

Although the surviving literary sources on the Persian empire were written by ancient Greeks who were the sworn enemies of the Persians and highly contemptuous of them, the Persians were in fact quite tolerant and ruled a multi-ethnic empire. Persia was the first empire known to have acknowledged the different faiths, languages and political organizations of its subjects.

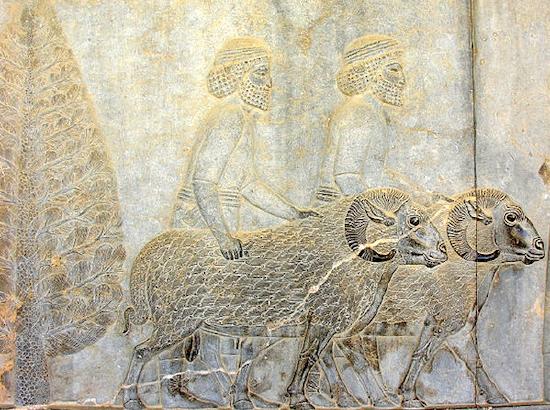

This tolerance for the cultures under Persian control carried over into administration. In the lands which they conquered, the Persians continued to use indigenous languages and administrative structures. For example, the Persians accepted hieroglyphic script written on papyrus in Egypt and traditional Babylonian record keeping in cuneiform in Mesopotamia. The Persians must have been very proud of this new approach to empire as can be seen in the representation of the many different peoples in the reliefs from Persepolis, a city founded by Darius the Great in the 6th century BCE.

Conquered by Alexander the Great

The Persian Empire was, famously, conquered by Alexander the Great. Alexander no doubt was impressed by the Persian system of absorbing and retaining local language and traditions as he imitated this system himself in the vast lands he won in battle. Indeed, Alexander made a point of burying the last Persian emperor, Darius III, in a lavish and respectful way in the royal tombs near Persepolis. This enabled Alexander to claim title to the Persian throne and legitimize his control over the greatest empire of the Ancient Near East.

Persepolis: The Audience Hall of Darius and Xerxes

by Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker

By the early fifth century BCE, the Achaemenid (Persian) Empire ruled an estimated 44% of the human population of planet Earth. Through regional administrators the Persian kings controlled a vast territory which they constantly sought to expand. Famous for monumental architecture, Persian kings established numerous monumental centers, among those is Persepolis (today, in Iran). The great audience hall of the Persian kings Darius and Xerxes presents a visual microcosm of the Achaemenid empire—making clear, through sculptural decoration, that the Persian king ruled over all of the subjugated ambassadors and vassals (who are shown bringing tribute in an endless eternal procession).

Overview of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire (First Persian Empire) was an imperial state of Western Asia founded by Cyrus the Great and flourishing from c. 550-330 BCE. The empire’s territory was vast, stretching from the Balkan peninsula in the west to the Indus River valley in the east. The Achaemenid Empire is notable for its strong, centralized bureaucracy that had, at its head, a king and relied upon regional satraps (regional governors).

A number of formerly independent states were made subject to the Persian Empire. These states covered a vast territory from central Asia and Afghanistan in the east to Asia Minor, Egypt, Libya, and Macedonia in the west. The Persians famously attempted to expand their empire further to include mainland Greece but they were ultimately defeated in this attempt (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). The Persian kings are noted for their penchant for monumental art and architecture. In creating monumental centers, including Persepolis, the Persian kings employed art and architecture to craft messages that helped to reinforce their claims to power and depict, iconographically, Persian rule.

Overview of Persepolis

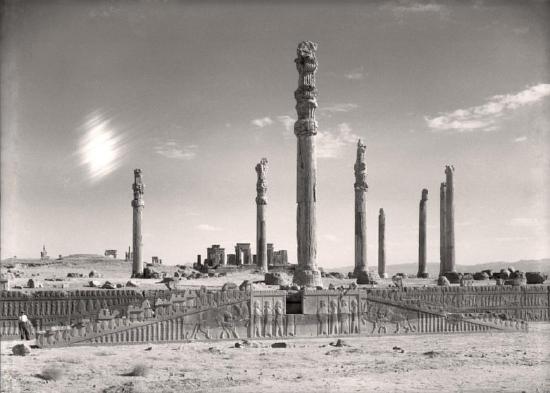

Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Persian empire (c. 550-330 BCE), lies some 60 km northeast of Shiraz, Iran. The earliest archaeological remains of the city date to c. 515 BCE. Persepolis, a Greek toponym meaning “city of the Persians,” was known to the Persians as Pārsa and was an important city of the ancient world, renowned for its monumental art and architecture. The site was excavated by German archaeologists Ernst Herzfeld, Friedrich Krefter, and Erich Schmidt between 1931 and 1939. Its remains are striking even today, leading UNESCO to register the site as a World Heritage Site in 1979.

Persepolis was intentionally founded in the Marvdašt Plain during the later part of the sixth century BCE. It was marked as a special site by Darius the Great (reigned 522-486 BCE) in 518 BCE when he indicated the location of a “Royal Hill” that would serve as a ceremonial center and citadel for the city. This was an action on Darius’ part that was similar to the earlier king Cyrus the Great who had founded the city of Pasargadae. Darius the Great directed a massive building program at Persepolis that would continue under his successors Xerxes (r. 486-466 BCE) and Artaxerxes I (r. 466-424 BCE). Persepolis would remain an important site until it was sacked, looted, and burned under Alexander the Great of Macedon in 330 BCE.

_(cropped).jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=907&height=302)

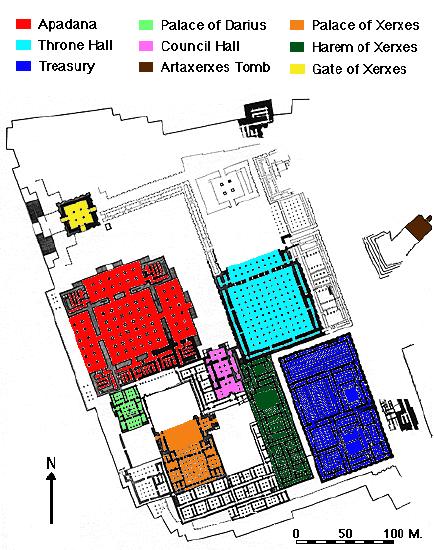

Darius’ program at Persepolis including the building of a massive terraced platform covering 125,000 square meters of the promontory. This platform supported four groups of structures: residential quarters, a treasury, ceremonial palaces, and fortifications. Scholars continue to debate the purpose and nature of the site. Primary sources indicate that Darius saw himself building an important stronghold. Some scholars suggest that the site has a sacred connection to the god Mithra (Mehr), as well as links to the Nowruz, the Persian New Year’s festival. More general readings see Persepolis as an important administrative and economic center of the Persian empire.

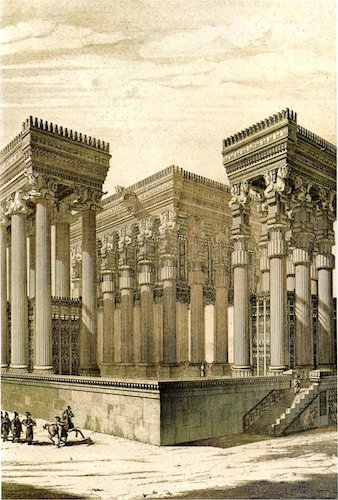

Apādana

The Apādana palace is a large ceremonial building, likely an audience hall with an associated portico. The audience hall itself is hypostyle in its plan, meaning that the roof of the structure is supported by columns. Apādana is the Persian term equivalent to the Greek hypostyle (Ancient Greek: ὑπόστυλος hypóstȳlos). The footprint of the Apādana is c. 1,000 square meters; originally 72 columns, each standing to a height of 24 meters, supported the roof (only 14 columns remain standing today). The column capitals assumed the form of either twin-headed bulls (as seen in Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)), eagles or lions, all animals that represented royal authority and kingship.

The king of the Achaemenid Persian empire is presumed to have received guests and tribute in this soaring, imposing space. To that end a sculptural program decorates monumental stairways on the north and east. The theme of that program is one that pays tribute to the Persian king himself as it depicts representatives of 23 subject nations bearing gifts to the king.

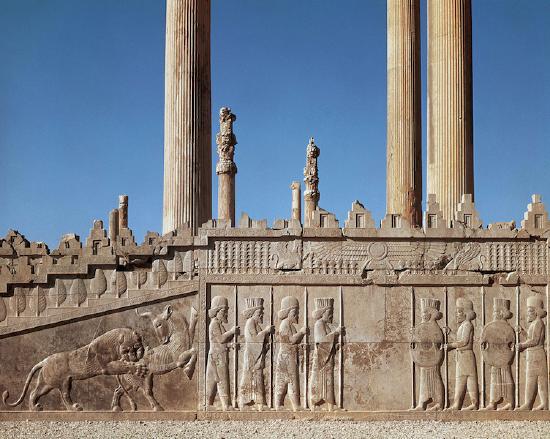

The Apādana stairs and sculptural program

The monumental stairways that approach the Apādana from the north and the east (Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)) were adorned with registers of relief sculpture that depicted representatives of the twenty-three subject nations of the Persian empire bringing valuable gifts as tribute to the king. The sculptures form a processional scene, leading some scholars to conclude that the reliefs capture the scene of actual, annual tribute processions—perhaps on the occasion of the Persian New Year–that took place at Persepolis. The relief program of the northern stairway was perhaps completed c. 500-490 BCE. The two sets of stairway reliefs mirror and complement each other. Each program has a central scene of the enthroned king flanked by his attendants and guards.

Noblemen wearing elite outfits and military apparel are also present. The representatives of the twenty-three nations, each led by an attendant, bring tribute while dressed in costumes suggestive of their land of origin. Margaret Root interprets the central scenes of the enthroned king as the focal point of the overall composition, perhaps even reflecting events that took place within the Apādana itself.

The relief program of the Apādana serves to reinforce and underscore the power of the Persian king and the breadth of his dominion. The motif of subjugated peoples contributing their wealth to the empire’s central authority serves to visually cement this political dominance. These processional scenes may have exerted influence beyond the Persian sphere, as some scholars have discussed the possibility that Persian relief sculpture from Persepolis may have influenced Athenian sculptors of the fifth century BCE who were tasked with creating the Ionic frieze of the Parthenon in Athens. In any case, the Apādana, both as a building and as an ideological tableau, make clear and strong statements about the authority of the Persian king and present a visually unified idea of the immense Achaemenid empire.

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Senta German, "Ancient Persia, an introduction," in Smarthistory, June 8, 2018 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Jeffrey A. Becker, "Persepolis: The Audience Hall of Darius and Xerxes," in Smarthistory, January 24, 2016 (CC BY-NC-SA)