5.3: Neolithic Art

- Page ID

- 109189

The Neolithic revolution

by Dr. Senta German

A settled life

When people think of the Neolithic era, they often think of Stonehenge, the iconic image of this early time. Dating to approximately 3,000 BCE and set on Salisbury Plain in England, it is a structure larger and more complex than anything built before it in Europe. Stonehenge is an example of the cultural advances brought about by the Neolithic revolution—the most important development in human history. The way we live today, settled in homes, close to other people in towns and cities, protected by laws, eating food grown on farms, and with leisure time to learn, explore and invent is all a result of the Neolithic revolution, which occurred approximately 11,500-5,000 years ago. The revolution which led to our way of life was the development of the technology needed to plant and harvest crops and to domesticate animals.

Before the Neolithic revolution, it’s likely you would have lived with your extended family as a nomad, never staying anywhere for more than a few months, always living in temporary shelters, always searching for food and never owning anything you couldn’t easily pack in a pocket or a sack. The change to the Neolithic way of life was huge and led to many of the pleasures (lots of food, friends and a comfortable home) that we still enjoy today.

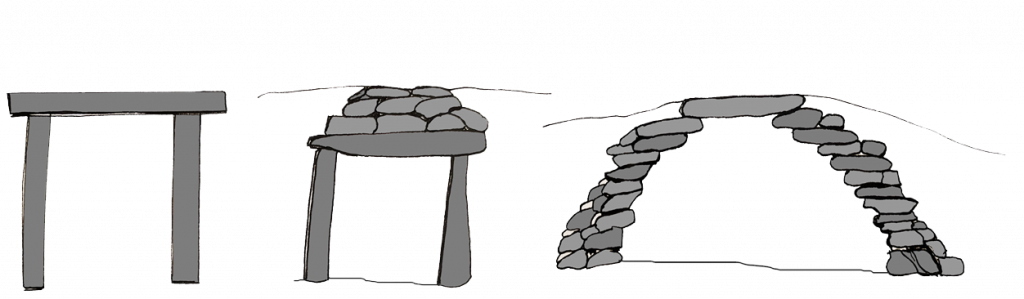

Each of the trilithons that form Stonehenge is comprised of three megaliths: two uprights and one balanced across the top. Post-and-lintel is a construction technique used in the Neolithic period and well beyond. It was used for both above-ground structures and underground burial chambers. Another building technique developed in the Neolithic period is the corbeled dome, as can be seen at the passage tomb at Newgrange.

Neolithic art

The massive changes in the way people lived also changed the types of art they made. Neolithic sculpture became bigger, in part, because people didn’t have to carry it around anymore; pottery became more widespread and was used to store food harvested from farms. Alcohol was first produced during this period and architecture, as well as its interior and exterior decoration, first appears. In short, people settled down and began to live in one place, year after year.

It seems very unlikely that Stonehenge could have been made by earlier, Paleolithic, nomads. It would have been a waste to invest so much time and energy building a monument in a place to which they might never return or might only return infrequently. After all, the effort to build it was extraordinary. Stonehenge is approximately 320 feet in circumference and the stones which compose the outer ring weigh as much as 50 tons; the small stones, weighing as much as 6 tons, were quarried from as far away as 450 miles. The use or meaning of Stonehenge is not clear, but the design, planning and execution could have only been carried out by a culture in which authority was unquestioned. Here is a culture that was able to rally hundreds of people to perform very hard work for extended periods of time. This is another characteristic of the Neolithic era.

Plastered skulls

The Neolithic period is also important because it is when we first find good evidence for religious practice, a perpetual inspiration for the fine arts. Perhaps most fascinating are the plaster skulls found around the area of the Levant, at six sites, including Jericho. At this time in the Neolithic, c. 7000-6,000 BCE, people were often buried under the floors of homes, and in some cases their skulls were removed and covered with plaster in order to create very life-like faces, complete with shells inset for eyes and paint to imitate hair and mustaches (see Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

The traditional interpretation of these the skulls has been that they offered a means of preserving and worshiping male ancestors. However, recent research has shown that among the sixty-one plastered skulls that have been found, there is a generous number that come from the bodies of women and children. Perhaps the skulls are not so much religious objects but rather powerful images made to aid in mourning lost loved ones.

Neolithic peoples didn’t have written language, so we may never know what their creators intended. (The earliest example of writing develops in Sumer in Mesopotamia in the late 4th millennium BCE. However, there are scholars that believe that earlier proto-writing developed during the Neolithic period).

Neolithic cultures around the world created pottery by hand, often using what is now called the coil construction method. Coil construction is simple in theory, but can be executed on a large and complex scale. Starting with a clay base, artists roll clay into cylindrical “snakes,” or coils, then layer them on top of each other to create the walls of the vessel, which grow from the bottom up. Once the clay coils are in place, artists use slip (clay thinned with water), tools, and their hands to smooth both the inside and outside of the vessel walls.

Japan has a particularly long and impressive pottery tradition, with pottery from the Jōmon period (which coincides with the Neolithic period discussed in this chapter) dating back to about 14,500 BCE. The Japanese word Jōmon, from which this period gets its name, means “cord pattern” in Japanese. During this period, makers used the coil construction method to build vessels and then decorated the exterior with distinctive geometric patterns created by pressing cords against the clay before it was dried, hardened, and fired. Vessels were made for both utilitarian and ceremonial purposes, and it is clear from the attention paid to their decoration that aesthetic value was also important in Jōmon pottery.

Coil construction was also commonly used to build Nasca ceramics in Peru. These vessels date back to 100 BCE and are known for their extremely glossy finish, achieved by smoothing and polishing the surface of the ceramic vessels using slip made from mineral pigments. Much later, Mogollon ceramicists from the Greater Southwest region of present-day Mexico and the United States also used a similar coil and scrape construction to achieve the smooth and characteristic red-on-brown, brown, or black-on-white finish of Mimbres pottery, which is decorated with both geometric and figural designs.

Jericho

by Dr. Senta German

A natural oasis

The site of Jericho, just north of the Dead Sea and due west of the Jordan River, is one of the oldest continuously lived-in cities in the world. The reason for this may be found in its Arabic name, Ārīḥā, which means fragrant; Jericho is a natural oasis in the desert where countless fresh water springs can be found. This resource, which drew its first visitors between 10,000 and 9000 BCE, still has descendants that live there today.

Biblical reference

The site of Jericho is best known for its identity in the Bible and this has drawn pilgrims and explorers to it as early as the 4th century CE; serious archaeological exploration didn’t begin until the latter half of the 19th century. What continues to draw archaeologists to Jericho today is the hope of finding some evidence of the warrior Joshua, who led the Israelites to an unlikely victory against the Canaanites (“the walls of the city fell when Joshua and his men marched around them blowing horns” Joshua 6:1-27). Although unequivocal evidence of Joshua himself has yet to be found, what has been uncovered are some 12,000 years of human activity.

The most spectacular finds at Jericho, however, do not date to the time of Joshua, roughly the Bronze Age (3300-1200 BCE), but rather to the earliest part of the Neolithic era, before even the technology to make pottery had been discovered.

Old walls

The site of Jericho rises above the wide plain of the Jordan Valley, its height the result of layer upon layer of human habitation, a formation called a tell. The earliest visitors to the site who left remains (stone tools) came in the Mesolithic period (around 9000 BCE) but the first settlement at the site, around the Ein as-Sultan spring, dates to the early Neolithic era, and these people, who built homes, grew plants, and kept animals, were among the earliest to do such anywhere in the world. Specifically, in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A levels at Jericho (8500-7000 BCE), archaeologists found remains of a very large settlement of circular homes made with mud brick and topped with domed roofs.

As the name of this era implies, these early people at Jericho had not yet figured out how to make pottery, but they made vessels out of stone, wove cloth and for tools were trading for a particularly useful kind of stone, obsidian, from as far away as Çiftlik, in eastern Turkey. The settlement grew quickly and, for reasons unknown, the inhabitants soon constructed a substantial stone wall and exterior ditch around their town, complete with a stone tower almost eight meters high, set against the inner side of the wall (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). Theories as to the function of this wall range from military defense to keeping out animal predators to even combating the natural rising of the level of the ground surrounding the settlement. However, regardless of its original use, here we have the first version of the walls Joshua so ably conquered some six thousand years later.

Plastered human skulls

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A period is followed by the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (7000-5200 BCE), which was different from its predecessor in important ways. Houses in this era were uniformly rectangular and constructed with a new kind of rectangular mud bricks which were decorated with herringbone thumb impressions, and always laid lengthwise in thick mud mortar. This mortar, like a plaster, was also used to create a smooth surface on the interior walls, extending down across the floors as well. In this period there is some strong evidence for cult or religious belief at Jericho. Archaeologists discovered one uniquely large building dating to the period with unique series of plastered interior pits and basins as well as domed adjoining structures and it is thought this was for ceremonial use.

Other possible evidence of cult practice was discovered in several homes of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic town, in the form of plastered human skulls which were molded over to resemble living heads. Shells were used for eyes and traces of paint revealed that skin and hair were also included in the representations. The largest group found together were nine examples, buried in the fill below the plastered floor of one house.

Jericho isn’t the only site at which plastered skulls have been found in Pre-Pottery Neolithic B levels; they have also been found at Tell Ramad, Beisamoun, Kfar Hahoresh, ‘Ain Ghazal and Nahal Hemar. Among the some sixty-two skulls discovered among these sites, we know that older and younger men as well as women and children are represented, which poses interesting questions as to their meaning. Were they focal points in ancestor worship, as was originally thought, or did they function as images by which deceased family members could be remembered? As we are without any written record of the belief system practiced in the Neolithic period in the area, we will never know.

by The British Museum

Over many years, Curator Alexandra Fletcher has formed a particularly strong bond with one of the… older people in the British Museum. In fact, she was one of the first to see his face in over 9,500 years. The Jericho Skull is arguably the oldest portrait in the British Museum—a human skull from the ancient city of Jericho which had plaster applied to it to form a type of early facial reconstruction.

The Jericho Skull is fascinating to look at, but since being discovered in 1953, archaeologists weren’t able to find out much more about this man—until now. Using CT scanning, 3D printing and facial reconstruction, Alexandra and her team have finally been able to reveal the man behind the plaster.

Also check out The Jericho Skull by The British Museum on Sketchfab

The inhabitants of Neolithic Jericho were not the only ones to bury objects beneath the floors of their houses. In another notable Paleolithic settlement near Aman, Jordan, called 'Ain Ghazal, archaeologists unearthed two caches of buried objects. Like the Jericho skulls, they consisted of plaster applied to a supporting structure, though in this case that structure was not hard bone, but bundles of reeds. Despite their fragile material, these sculptures are much larger than other early art of the era; the largest of them is nearly three and a half feet tall (though only about four inches thick). Although abstract and with distorted proportions, the figures are immediately recognizable as human. Their most striking feature is their stylized, staring eyes, which are outlined and detailed with bitumen. Because of the absence of written records, as with all Stone Age art, we do not know why these objects were made nor how they were used. What we do know is that time, skill, and resources were invested into them, highlighting the importance of image-making for even our earliest ancestors.

Çatalhöyük

By Dr. Senta German

Çatalhöyük or Çatal Höyük (pronounced “cha-tal hay OOK”) is not the oldest site of the Neolithic era or the largest, but it is extremely important to the beginning of art. Located near the modern city of Konya in south central Turkey, it was inhabited 9000 years ago by up to 8000 people who lived together in a large town. Çatalhöyük, across its history, witnesses the transition from exclusively hunting and gathering subsistence to increasing skill in plant and animal domestication. We might see Çatalhöyük as a site whose history is about one of man’s most important transformations: from nomad to settler. It is also a site at which we see art, both painting and sculpture, appear to play a newly important role in the lives of settled people.

Çatalhöyük had no streets or foot paths; the houses were built right up against each other (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)) and the people who lived in them traveled over the town’s rooftops and entered their homes through holes in the roofs, climbing down a ladder. Communal ovens were built above the homes of Çatalhöyük and we can assume group activities were performed in this elevated space as well.

Çatalhöyük, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Like at Jericho, the deceased were placed under the floors or platforms in houses and sometimes the skulls were removed and plastered to resemble live faces. The burials at Çatalhöyük show no significant variations, either based on wealth or gender; the only bodies which were treated differently, decorated with beads and covered with ochre, were those of children. The excavator of Çatalhöyük believes that this special concern for youths at the site may be a reflection of the society becoming more sedentary and required larger numbers of children because of increased labor, exchange and inheritance needs.

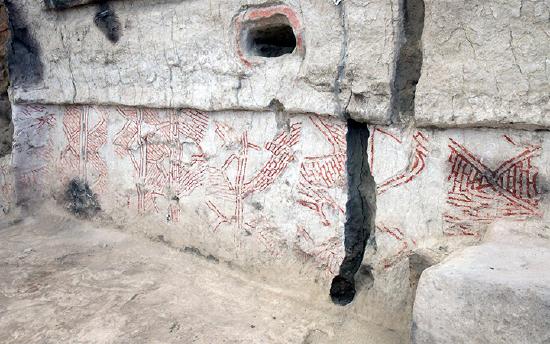

Art is everywhere among the remains of Çatalhöyük, geometric designs as well as representations of animals and people. Repeated lozenges and zigzags dance across smooth plaster walls, people are sculpted in clay, pairs of leopards are formed in relief facing one another at the sides of rooms, hunting parties are painted baiting a wild bull. The volume and variety of art at Çatalhöyük is immense and must be understood as a vital, functional part of the everyday lives of its ancient inhabitants.

Many figurines have been found at the site, the most famous of which illustrates a large woman seated on or between two large felines. The figurines, which illustrate both humans and animals, are made from a variety of materials but the largest proportion are quite small and made of barely fired clay. These casual figurines are found most frequently in garbage pits, but also in oven walls, house walls, floors and left in abandoned structures. The figurines often show evidence of having been poked, scratched or broken, and it is generally believed that they functioned as wish tokens or to ward off bad spirits.

Nearly every house excavated at Çatalhöyük was found to contain decorations on its walls and platforms, most often in the main room of the house. Moreover, this work was constantly being renewed; the plaster of the main room of a house seems to have been redone as frequently as every month or season. Both geometric and figural images were popular in two-dimensional wall painting and the excavator of the site believes that geometric wall painting was particularly associated with adjacent buried youths. Figural paintings show the animal world alone, such as, for instance, two cranes facing each other standing behind a fox, or in interaction with people, such as a vulture pecking at a human corpse or hunting scenes. Wall reliefs are found at Çatalhöyük with some frequency, most often representing animals, such as pairs of animals facing each other and human-like creatures. These latter reliefs, alternatively thought to be bears, goddesses or regular humans, are always represented splayed, with their heads, hands and feet removed, presumably at the time the house was abandoned.

The most remarkable art found at Çatalhöyük, however, are the installations of animal remains and among these the most striking are the bull bucrania. In many houses the main room was decorated with several plastered skulls of bulls set into the walls (most common on East or West walls) or platforms, the pointed horns thrust out into the communal space. Often the bucrania would be painted ochre red. In addition to these, the remains of other animals’ skulls, teeth, beaks, tusks or horns were set into the walls and platforms, plastered and painted. It would appear that the ancient residents of Çatalhöyük were only interested in taking the pointy parts of the animals back to their homes!

How can we possibly understand this practice of interior decoration with the remains of animals? A clue might be in the types of creatures found and represented. Most of the animals represented in the art of Çatalhöyük were not domesticated; wild animals dominate the art at the site. Interestingly, examination of bone refuse shows that the majority of the meat which was consumed was of wild animals, especially bulls. The excavator believes this selection in art and cuisine had to do with the contemporary era of increased domestication of animals and what is being celebrated are the animals which are part of the memory of the recent cultural past, when hunting was much more important for survival.

Rock Art in North Africa

by The British Museum

Forests of Stone

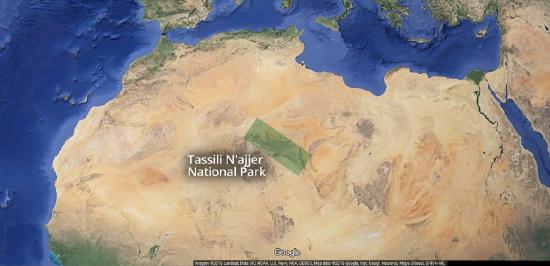

Algeria is Africa’s largest country and most of it falls within the Sahara Desert. It also hosts a rich rock art concentration. Most of the sites are found in the south east of the country near its borders with Libya and Niger but there are also important concentrations in the Algerian Maghreb and in the Hoggar Mountains in the central south.

The most renowned of all these areas is the Tassili n’Ajjer (meaning “plateau of chasms”) in the south east. Water and sand erosion have carved out a landscape of thin passageways, large arches, and high-pillared rocks, described as “forests of stone” by French archaeologist and ethnographer Henri Lhote. The resulting undercuts at cliff bases have created rock shelters with smooth walls ideal for painting and engraving.

The Ajjer plateau rises to approximately 500-600 meters above the plain of Djanet, an oasis city, and capital of Djanet District, in Illizi Province, southeast Algeria. The region has been inhabited since Neolithic times, when the environment was much wetter and sustained a wider extent of flora and fauna as witnessed in the numerous rock paintings of Tassili n’Ajjer. Classified as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1982 and Biosphere Reserve in 1986, Tassili n’Ajjer covers a vast area of desert landscape in southern Algeria, stretching from the Niger and Libyan border area, north and east of Djanet, as far as Illizi and Amguid, covering an area of 72,000 sq. km.

The rock art of the Tassili region was introduced to Western eyes as a result of visits and sketches made by French legionnaires, in particular a Lt. Brenans during the 1930s. On several of his expeditions, Lt. Brenans took French archaeologist Henri Lhote who went on to revisit sites in Algeria between 1956-1970 documenting and recording the images he found. Regrettably, some previous methods of recording and/or documenting have caused damage to the vibrancy and integrity of the images.

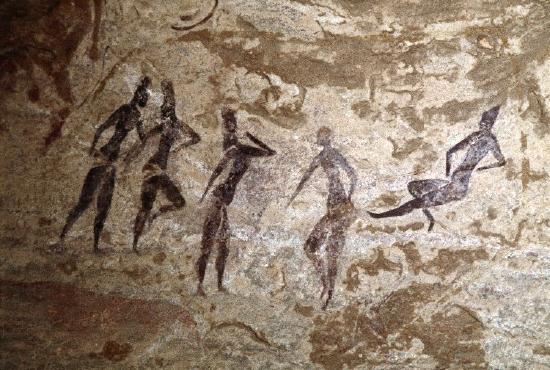

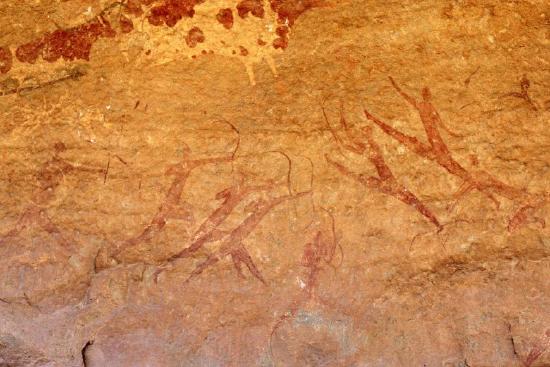

Subject matter

More than 15,000 rock paintings and engravings, dating back as far as 12,000 years are located in this region and have made Tassili world famous for this reason. The art depicts herds of cattle and large wild animals such as giraffe and elephant, as well as human activities such as hunting and dancing. The area is especially famous for its Round Head paintings which were first described and published by Henri Lhote in the 1950s. Thought to date from around 9,000 years old, some of these paintings are the largest found on the African continent, measuring up to 13 feet in height.

Although the styles and subjects of north African rock art vary, there are commonalities: images are most often figurative and frequently depict animals, both wild and domestic. There are also many images of human figures, sometimes with accessories such as recognizable weaponry or clothing. These may be painted (Figure \(\PageIndex{19}\)) or engraved, with frequent occurrences of both, at times in the same context. Engravings are generally more common, although this may simply be a preservation bias due to their greater durability.

The physical context of rock art sites varies depending on geographical and topographical factors—for example, Moroccan rock engravings are often found on open rocky outcrops, while Tunisia’s Djebibina rock art sites have all been found in rock shelters. Rock art in the vast and harsh environments of the Sahara is often inaccessible and hard to find, and there is probably a great deal of rock art that is yet to be seen by archaeologists; what is known has mostly been documented within the last century.

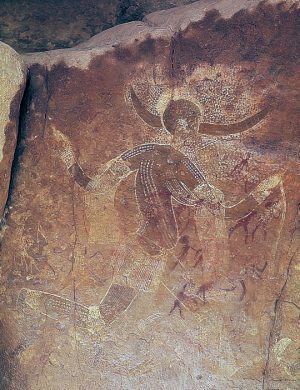

Running Horned Woman, Tassili n’Ajjer, Algeria

by Nathalie Hager

“Discovery”

Between 1933 and 1940, camel corps officer Lieutenant Brenans of the French Foreign Legion completed a series of small sketches and hand written notes detailing his discovery of dozens of rock art sites deep within the canyons of the Tassili n’Ajjer. Tassili n’Ajjer is a difficult to access plateau in the Algerian section of the Sahara Desert near the borders of Libya and Niger in northern Africa (see map below). Brenans donated hundreds of his sketches to the Bardo Museum in Algiers, alerting the scientific community to one of the richest rock art concentrations on Earth and prompting site visits that included fellow Frenchman and archaeologist Henri Lhote.

Lhote recognized the importance of the region and returned again and again, most notably in 1956 with a team of copyists for a 16 month expedition to map and study the rock art of the Tassili. Two years later Lhote published A la découverte des fresques du Tassili. The book became an instant best-seller, and today is one of the most popular texts on archaeological discovery.

Lhote made African rock art famous by bringing some of the estimated 15,000 human figure and animal paintings and engravings found on the rock walls of the Tassili’s many gorges and shelters it to the wider public. Yet contrary to the impression left by the title of his book, neither Lhote nor his team could lay claim to having discovered Central Saharan rock art: long before Lhote, and even before Brenans, in the late nineteenth century a number of travelers from Germany, Switzerland, and France had noted the existence of “strange” and “important” rock sculptures in Ghat, Tadrart Acacus, and Upper Tassili. But it was the Tuareg—the indigenous peoples of the region, many of whom served as guides to these early European explorers—who long knew of the paintings and engravings covering the rock faces of the Tassili.

The “Horned Goddess”

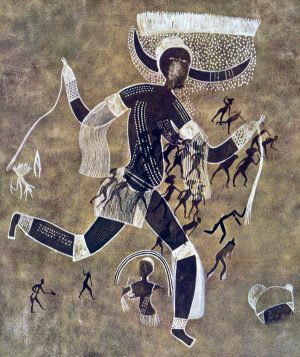

Lhote published not only reproductions of the paintings and engravings he found on the rock walls of the Tassili, but also his observations. In one excerpt he reported that with a can of water and a sponge in hand he set out to investigate a “curious figure” spotted by a member of his team in an isolated rock shelter located within a compact group of mountains known as the Aouanrhet massif, the highest of all the “rock cities” on the Tassili. Lhote swabbed the wall with water to reveal a figure he called the “Horned Goddess” (Figure \(\PageIndex{20}\)):

On the damp rock surface stood out the gracious silhouette of a woman running. One of her legs, slightly flexed, just touched the ground, while the other was raised in the air as high as it would normally go. From the knees, the belt and the widely outstretched arms fell fine fringes. From either side of the head and above two horns that spread out horizontally was an extensive dotted area resembling a cloud of grain falling from a wheat field. Although the whole assemblage was skillfully and carefully composed there was something free and easy about it…

The Running Horned Woman, the title by which the painting is commonly known today, was found in a massif so secluded and so difficult to access that Lhote’s team concluded that the collection of shelters was likely a sanctuary and the female figure—“the most beautiful, the most finished and the most original”—a goddess:

Perhaps we have here the figure of a priestess of some agricultural religion or the picture of a goddess of such a cult who foreshadow—or is derived from—the goddess Isis, to whom, in Egypt, was attributed the discovery of agriculture.

Lhote’s suggestion that the painting’s source was Egyptian was influenced by a recently published hypothesis by his mentor, the French anthropologist Henri Breuil, the then undisputed authority on prehistoric rock art who was renowned for his work on Paleolithic cave art in Europe. In an essay titled, “The White Lady of Brandberg, South-West Africa, Her Companions and Her Guards,” Breuil famously claimed that a painting discovered in a small rock shelter in Namibia showed influences of Classical antiquity and was not African in origin, but possibly the work of Phoenician travelers from the Mediterranean. Lhote, equally convinced of outside influence, linked the Tassili painting’s provenance with Breuil’s ideas and revised the title to the ‘White Lady’ of Aouanrhet:

In other paintings found a few days later in the same massif we were able to discern, from some characteristic features, an indication of Egyptian influence. Some features are, no doubt, not very marked in our ‘White Lady’; still, all the same, some details as the curve of the breasts, led us to think that the picture may have been executed at a time when Egyptian traditions were beginning to be felt in the Tassili.

Foreign influence?

Time and scholarship would reveal that the assignment of Egyptian influence on the Running Horned Woman was erroneous, and Lhote the victim of a hoax: French members of his team made “copies” of Egyptionized figures, passing them off as faithful reproductions of authentic Tassili rock wall paintings. These fakes were accepted by Lhote (if indeed he knew nothing of the forgeries), and falsely sustained his belief in the possibility of foreign influence on Central Saharan rock art. Breuil’s theories were likewise discredited: the myth of the “White Lady” was rejected by every archaeologist of repute, and his promotion of foreign influence viewed as racist.

Yet Breuil and Lhote were not alone in finding it hard to believe that ancient Africans discovered how to make art on their own, or to have developed artistic sensibilities. Until quite recently many Europeans maintained that art “spread” or was “taken” into Africa, and, aiming to prove this thesis, anointed many works with Classical sounding names and sought out similarities with early rock art in Europe. Although such vestiges of colonial thinking are today facing a reckoning, cases such as the “White Lady” (both of Namibia and of Tassili) remind us of the perils of imposing cultural values from the outside.

Chronology

While we have yet to learn how, and in what places, the practice of rock art began, no firm evidence has been found to show that African rock art—some ten million images across the continent—was anything other than a spontaneous initiative by early Africans. Scholars have estimated the earliest art to date to 12,000 or more years ago, yet despite the use of both direct and indirect dating techniques very few firm dates exist (“direct dating” uses measurable physical and chemical analysis, such as radiocarbon dating, while “indirect dating” primarily uses associations from the archaeological context). In the north, where rock art tends to be quite diverse, research has focused on providing detailed descriptions of the art and placing works in chronological sequence based on style and content. This ordering approach results in useful classification and dating systems, dividing the Tassili paintings and engravings into periods of concurrent and overlapping traditions (the Running Horned Woman is estimated to date to approximately 6,000 to 4,000 BCE—placing it within the “Round Head Period”), but offers little in the way of interpretation of the painting itself.

Advancing an interpretation of the Running Horned Woman

Who was the Running Horned Woman? Was she indeed a goddess, and her rock shelter some sort of sanctuary? What does the image mean? And why did the artist make it? For so long the search for meaning in rock art was considered inappropriate and unachievable—only recently have scholars endeavored to move beyond the mere description of images and styles, and, using a variety of interdisciplinary methods, make serious attempts to interpret the rock art of the Central Sahara.

Lhote recounted that the Running Horned Woman was found on an isolated rock whose base was hollowed out into a number of small shelters that could not have been used as dwellings. This remote location, coupled with an image of marked pictorial quality—depicting a female with two horns on her head, dots on her body probably representing scarification, and wearing such attributes of the dance as armlets and garters—suggested to him that the site, and the subject of the painting, fell outside of the everyday. More recent scholarship has supported Lhote’s belief in the painting’s symbolic, rather than literal, representation. As Jitka Soukopova has noted, “Hunter- gatherers were unlikely to wear horns (or other accessories on the head) and to make paintings on their whole bodies in their ordinary life.” [1] . Rather, this female horned figure, her body adorned and decorated, found in one of the highest massifs in the Tassili—a region is believed to hold special status due to its elevation and unique topology—suggests ritual, rite, or ceremony.

But there is further work to be done to advance an interpretation of the Running Horned Woman. Increasingly scholars have studied rock shelter sites as a whole, rather than isolating individual depictions, and the shelter’s location relative to the overall landscape and nearby water courses, in order to learn the significance of various “rock cities” in both image making and image viewing.

Archaeological data from decorated pottery, which is a dated artistic tradition, is key in suggesting that the concept of art was firmly established in the Central Sahara at the time of Tassili rock art production. Comparative studies with other rock art complexes, specifically the search for similarities in fundamental concepts in African religious beliefs, might yield the most fruitful approaches to interpretation. In other words, just as southern African rock studies have benefitted from tracing the beliefs and practices of the San people, so too may a study of Tuareg ethnography shed light on the ancient rock art sites of the Tassili.

Afterword: the threatened rock art of the Central Sahara

Tassili’s rock walls were commonly sponged with water in order to enhance the reproduction of its images, either in trace, sketch, or photograph. This washing of the rock face has had a devastating effect on the art, upsetting the physical, chemical, and biological balance of the images and their rock supports. Many of the region’s subsequent visitors—tourists, collectors, photographers, and the next generation of researchers—all captivated by Lhote’s “discovery”—have continued the practice of moistening the paintings in order to reveal them. Today scholars report paintings that are severely faded while some have simply disappeared. In addition, others have suffered from irreversible damage caused by outright vandalism: art looted or stolen as souvenirs. In order to protect this valuable center of African rock art heritage, Tassili N’Ajjer was declared a National Park in 1972. It was classified as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1982 and a Biosphere Reserve in 1986.

[1] Jitka Soukopova, “The Earliest Rock Paintings of the Central Sahara: Approaching Interpretation,” Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness and Culture 4, no. 2 (2011), p. 199.

The British Museum, "Rock Art in the Green Sahara"

Articles in this section:

- Dr. Senta German, "The Neolithic revolution," in Smarthistory, June 8, 2018 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Senta German, "Jericho," in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Dr. Senta German, "Çatalhöyük," in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- The British Museum, "Rock Art in North Africa," in Smarthistory, September 23, 2016 (CC BY-NC-SA)

- Nathalie Hager, "Running Horned Woman, Tassili n’Ajjer, Algeria," in Smarthistory, September 23, 2016 (CC BY-NC-SA)