1.7: Camera Arts

- Page ID

- 143483

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)This is the one tool of art that – besides the pencil – most 21st century people have used, and often on a daily basis. Statistics suggest that every two minutes today we take as many photos as were taken in the entire 19th century, the century that saw the birth of modern photography.1 In this class, rather than trying to explain all of the chemical processes that made photography possible we will focus on the history of photography and how it fits within our study of the fine arts.

Early Development

The basic principle that photography is based on is the idea that light passing through a small opening will cast an image into a darkened space. It is suggested that a Chinese philosopher, Mo Ti, from the 5th century BCE was the first to notice and record this observation. Others repeated these experiments including Aristotle. Arab mathematician and physicist Abu Ali Hasan Ibn al-Haitham, in the West known as Alhazen, created experiments with candles and a darkened room that allowed him to correctly theorize that light travels in straight lines and that the human eye must work similarly. These ideas made their way to the West and during the Renaissance we see the first invention created to make use of this concept.

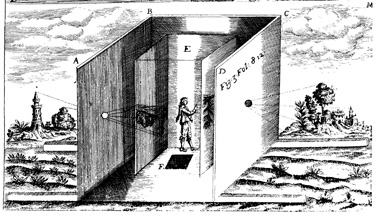

The first attempts to capture an image were made from a camera obscura, in use since the 16th century. The device consists of a box or small room with a small hole in one side that acts as a lens. Light from an external scene passes through the hole and strikes the opposite surface inside where it is reproduced upside-down, but with color and perspective preserved. The image can be projected onto paper adhered to the opposite wall, and then traced to produce a highly accurate representation. The technology to capture images made of light on a permanent surface wasn’t available until the 19th century, although experiments in capturing images on film had been conducted in Europe since the late 18th century.

Using the dynamics of the camera obscura as a model, early chemist photographers found ways to chemically fix the projected images onto metal plates coated with light sensitive materials like silver iodide. Moreover, they installed glass lenses in their early cameras and experimented with different exposure times for their images. View from the Window at Le Gras is one of the oldest existing photographs, taken in 1826 by French inventor Joseph Niepce using a process he called heliograpy (“helio” meaning sun and “graph” meaning write). The exposure for the image took eight hours, resulting in the sun casting its light on both sides of the houses in the picture. Further developments resulted in apertures — thin circular devices that are calibrated to allow a certain amount of light onto the exposed film. A wide aperture is used for low light conditions, while a smaller aperture is best for bright conditions. Apertures allowed photographers better control over their exposure times.

During the 1830’s Louis Daguerre, having worked with Niepce earlier, developed a more reliable process to capture images on film by using a polished copper plate treated with silver iodide. Not being one to hide his light under a bushel, as it were, he termed the images made by this process “Daguerreotypes.” They were sharper in focus and the exposure times were shorter. His photograph Boulevard du Temple from 1838 is taken from his studio window overlooking a busy Paris street. Still, with an exposure of ten minutes, none of the moving traffic or pedestrians stayed still long enough to be recorded. The only person in the image is a man on the lower left, standing at the corner getting his shoes shined.

The image that resulted from a daguerreotype was a single, positive image. It could not be reproduced. This limited the uses to which this new medium could be put. It would be only about two years before another inventor came up with a process for creating early negatives.

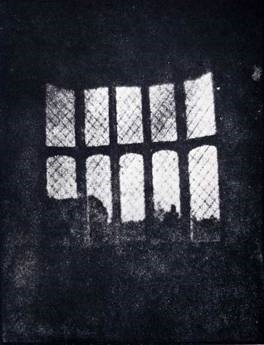

At the same time Daguerre was working in France, in England William Henry Fox Talbot was experimenting with other photographic processes. He was creating photogenic drawings by simply placing objects (mostly botanical specimens) over light sensitive paper or plates, then exposing them to the sun. By 1844 he had invented the calotype: a photographic print made from a negative image. In contrast, as stated above, Daguerreotypes were single, positive images that could not be reproduced. Talbot’s calotypes allowed for multiple prints from one negative, setting the standard for the new medium. Latticed Window at Lacock Abbey is a print made from the oldest photographic negative in existence.

By the middle of the 19th century the process for creating negatives on glass plates was created. The collodion process involved adding soluble iodide to a solution of cellulose nitrate on a glass plate. Now all that was needed was a light-sensitive paper onto which the negatives could be printed.2 Another French citizen, Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard, was the first to create a photographic paper using albumen – the white from chicken eggs – along with salt and silver nitrate. More on this process can be accessed here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Albumen_print

Now that the basic elements of reproduceable photographic processes was available the question was: what is photography for? One of the earliest and most popular uses was the same as it is today – to record the likenesses of ourselves and our loved ones. Portrait photography gave rise to commercial photographic studios in Europe and America. One successful entrepreneur was Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, known as Nadar. A Parisian, Nadar tried his hand at many things before opening his photographic studio in 1854. He had once been a caricaturist for newspapers and had met most of the celebrated artists, writers, and other creative people of the Parisian demi-monde. He would photograph such historical persons as actress Sarah Bernhardt, novelist Baudelaire, painter Delacroix, and musician Berlioz. One of his most famous sitters was Jules Verne, writer of early science fiction. Both men were enthusiasts of hot air ballooning – Nadar had commissioned one for himself – from which he made the first aerial photographs. Verne’s experiences in Nadar’s balloon would inspire his novel, Five Weeks in a Balloon.

Photography and Art

Until the advent of photography the only access to images was from media like paintings or drawings translated through the hand and eye of another person. During the 19th century an effort was made to place photography in the same league as oil painting and other fine arts and to demonstrate its aesthetic potential. To do this photographs were staged and manipulated (by hand) to create simulacrums of famous paintings, or to create images that suggested popular paintings of the day.

While this continues today, the desire to find a more authentic use for the photographic medium would give rise to other fields of visual and social experimentation.

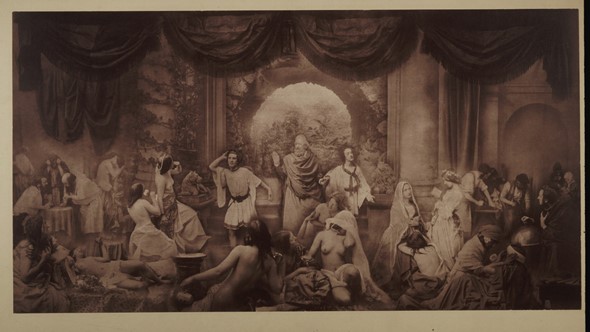

Thomas Couture’s Romans of the Decadence from 1847 was possibly the most famous painting of its day. Couture, an early instructor of Edouard Manet, described the aftermath of a Roman orgy in the classical style of the French Academy. Reilander’s photo, while not a strict recreation, nevertheless uses the same format and basic composition to describe the same moral position – in general, orgies are not good for you.

Photojournalism

Mathew Brady had a photographic studio in New York City when the Civil War began. Young soldiers and their families began coming to him for portraits – one of the soldier for his family to keep and one of the family for the soldier to take with him to the battlefield. He even somewhat cynically marketed these services to soldiers with the idea that you should do it before it’s too late. Brady saw a need for images from the war itself which would carry the impact of battle with more immediacy and empathy than could be communicated in the prints created by hand for the newspapers. In the 1860s newspapers couldn’t print halftone photographs and were restricted to images made by the hand of an artist.

To realize his project of photographing the war itself Brady had to find a way to develop the glass plates on the spot. He invented a “portable darkroom” from a carriage covered in a light impermeable tarp and sent his assistants like Gardner into the field. Because of the still-long exposure times actual battle scenes weren’t possible. The aftermath of the battle, however, was perfectly still and this was what Brady and his assistants captured. He exhibited one series, The Dead of Antietam, in his New York gallery bringing the real cost of the war home to the public. In many ways Brady might be thought of as the Father of modern photojournalism.

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California

During the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl that afflicted much of the middle of the country in the 1930s, the government gave employment to artists and photographers by sending them out to document the ordeal of the people. One of these was Dorothea Lange. With her Hasselblad camera she traveled throughout the Dust Bowl states taking photos of farms covered in dust and dead crops and on to California, the destination of many of the displaced farm families. One of these provided the photograph that was to prove iconic and would be used to spur the government to create unemployment insurance and other aid programs.

Florence Thompson and her seven children were sitting in a tent. They had hoped to pick peas but a freezing rain had destroyed the crop.3 Lange started snapping photos as she approached the tent and managed to capture the photo that would encapsulate the pain and suffering of the people during the Great Depression. Alongside Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, Migrant Mother documents a moment of American history that must be remembered.

Photography and Art

The discussion about art’s true nature and purpose continued into the twentieth century. Some continued to feel that it should mimic the look of paintings and drawings, but others believed that photography as an artform should be appreciated for the specific qualities of which it was uniquely capable. Alfred Stieglitz was a wealthy New Yorker who believed in photography as a unique art. On a trip back from Europe he captured a photo that would illustrate the nature of photography in its own right. The Steerage captures the below-deck quarters of the poorer people on Stieglitz’ voyage. He caught the moment when sun fell on a series of lines and walkways dividing the picture into two horizontal planes of light and dark. Joined by the walkway, the ladder on the right, and punctuated by the crown of the white straw boater of the man in the upper register, Stieglitz makes a case for pure photography showing all of the elements and principles of any other medium. To read more about Stieglitz and photography see Lisa Hostetler at: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/stgp/hd_stgp.htm

Contemporary Photography

Today photography is recognized as the equivalent of any other fine art and is sold in galleries and included in Art Fairs and museums all over the world. In 2007, this c-print (chromogenic print) by Andreas Gursky sold at auction for $3,346,456. The manipulated photo was taken in a California grocery store and compressed to suggest the vertical perspective of Eastern paintings.

Photography has at last come full circle, selling for as much as any major canvas and reflecting both the natural world of the subject and also the mind and hand of its maker. Digital photography has made photographers of us all and selfies continue the tradition of portraiture for which the medium was first thought best suited. The internet makes use of millions of images and makes them available for our use in a way never imagined by Stieglitz and other earlier photographers. Still, artists continue to push the limits of what the medium and technology can make it do.