1.5: Painting

- Page ID

- 143480

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)In his NaturalisHistoria, Pliny the Elder tells of a painting contest between the great Greek painter Zeuxis and his rival Parrhasius to decide who was the greatest artist. Zeuxis painted a still life of grapes that appeared so real birds flew down to peck at them. Parrhasius concealed his painting behind a curtain, and asked Zeuxis if he would please unveil it. When Zeuxis tried to pull the curtain aside it proved to be a painted illusion. Parrhasius was the winner, and Zeuxis was said to have generously exclaimed, “I have deceived the birds, but Parrhasius has deceived Zeuxis.” This historical anecdote is probably not entirely true, but it seems that Zeuxis, at least, was a great Greek painter. Sadly, the only examples of painting from the Greeks that survive are those on ceramics and in the wall frescoes of Pompeii and Herculaneum, but descriptions of the work of Zeuxis suggests it was well-developed and innovative, exhibiting many of the skills artists would only rediscover during the Renaissance. This chapter will introduce the materials and techniques of painting, both historical and still employed today.

Painting is the application of pigments to a support surface that establishes an image, design or decoration. In art, the term ‘painting’ describes both the act and the result. Most painting is created with pigment in liquid form applied with a brush. Exceptions to this are found in Navajo sand painting and Tibetan mandala painting, where powdered pigments are used. Painting as a medium has survived for thousands of years and is, along with drawing and sculpture, one of the oldest creative mediums. It’s used in some form by most cultures around the world.

Three of the most recognizable images in Western art history are paintings: Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Edvard Munch’s The Scream, and Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night. These three art works are examples of how painting can go beyond a simple mimetic function – that is, to only imitate what is seen. The power in great painting is that it transcends perceptions to reflect emotional, psychological, even spiritual levels of the human condition.

Painting mediums are extremely versatile because they can be applied to many different surfaces (called supports) including paper, wood, canvas, plaster, clay, lacquer, concrete and more. Because paint is usually applied in a liquid or semi-liquid state it has the ability to soak into porous support material, which can, over time, weaken and damage it. To prevent this a support is usually first covered with a ground, a mixture of binder and chalk that, when dry, creates a non-porous layer between the support and the painted surface. A typical ground is called “gesso”.

There are six major painting mediums, each with specific individual characteristics:

- Encaustic

- Fresco

- Tempera

- Oil

- Watercolor and Gouache

- Acrylic

All of them use three basic ingredients:

- Pigment

- Binder

- Solvent

Pigments are granular solids incorporated into the paint to contribute color. The binder, commonly referred to as the vehicle, is the actual film-forming component of paint. The binder holds the pigment in solution until it’s ready to be dispersed onto the surface. The solvent controls the flow and application of the paint. It’s mixed into the paint, usually with a brush, to dilute it to the proper viscosity, or thickness, before it’s applied to the surface. Once the solvent has evaporated from the surface the remaining paint is fixed there. Solvents range from water to oil-based products like linseed oil and mineral spirits. Let’s look at each of the six main painting mediums:

Encaustic

Encaustic paint mixes dry pigment with a heated beeswax binder. The mixture is then brushed or spread across a support surface. Reheating allows for longer manipulation of the paint. Encaustic dates back to at least the first century C.E. and was used extensively in funerary mummy portraits from Fayum in Egypt. The characteristics of encaustic painting include strong, resonant colors and extremely durable paintings. Because of the beeswax binder, when encaustic cools it forms a tough skin on the surface of the painting. Typically, the support used for encaustic must be rigid, like the wooden panels of the Fayum portraits, to keep the wax from cracking. Some modern artists have used more flexible supports, however, with mixed results.

The twentieth-century American artist, Jasper Johns used encaustic techniques in his compositions. In his work, ‘Flag‘ (1954-1955), Jasper used a combination of encaustic, oil, and collage on fabric mounted on plywood. In other works he used crumpled newsprint soaked in the encaustic, applied to the canvas, allowed to dry and then painted over. This technique, for Johns, suggested the exaggerated brushwork of the Abstract Expressionists without actually having done the brushwork. It was a cool, ironic employment of medium as “gesture.”

Tempera

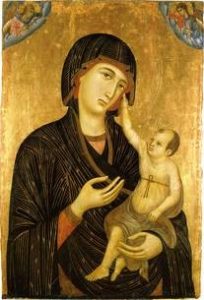

Tempera paint combines pigment with an egg yolk binder, then thinned and released with water. Like encaustic, tempera has been used for thousands of years. It dries quickly to a durable matte finish. Tempera paintings are traditionally applied in successive thin layers, called glazes, painstakingly built up using networks of cross hatched lines. Because of this technique tempera paintings are known for their detail.

In early Christianity, tempera was used extensively to paint images of religious icons. The pre-Renaissance Italian artist Duccio (c. 1255–1318), one of the most influential artists of the time, used tempera paint in the creation of ‘The CrevoleMadonna‘ (above). You can see the sharpness of line and shape in this well-preserved work, and the detail he renders in the face and skin tones of the Madonna (see the detail below).

Contemporary painters still use tempera as a medium. American painter Koo Schadler uses traditional methods and materials to create her poetic paintings of rabbits, flowers, and other still life and portrait objects. She prepares the surface of the support with multiple layers of gesso, dried, sanded, and reapplied to create a velvety smooth surface on which the egg-based tempera is applied.

Fresco

Fresco painting is used exclusively on plaster walls and ceilings. The medium of fresco has been used for thousands of years, but is most associated with its use in Christian images during the Renaissance period in Europe.

There are two forms of fresco: buon or “wet”, and secco, meaning “dry”.

Buon fresco technique consists of painting in pigment mixed with water on a thin layer of wet, fresh lime mortar or plaster. The pigment is applied to and absorbed by the wet plaster; after a number of hours, the plaster dries and reacts with the air: it is this chemical reaction that fixes the pigment particles in the plaster. Because of the chemical makeup of the plaster, a binder is not required. Buon fresco is more stable because the pigment becomes fused with the wall itself.

Domenico di Michelino’s ‘Dante and the Divine Comedy‘ from 1465 (below) is a superb example of buon fresco. The colors and details are preserved in the dried plaster wall. Michelino shows the Italian author and poet Dante Aleghieri standing with a copy of the Divine Comedy open in his left hand, gesturing to the illustration of the story depicted around him. The artist shows us four different realms associated with the narrative: the mortal realm on the right depicting Florence, Italy; the heavenly realm indicated by the stepped mountain at the left center – you can see an angel greeting the saved souls as they enter from the base of the mountain; the realm of the damned to the left – with Satan surrounded by flames greeting them at the bottom of the painting; and the realm of the cosmos arching over the entire scene.

Fresco secco refers to painting an image on the surface of a dry plaster wall. This medium requires a binder since the pigment is not mixed into the wet plaster. Egg tempera is the most common binder used for this purpose. It was common to use fresco secco over buon fresco murals in order to repair damage or make changes to the original.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s painting of ‘The Last Supper‘ (below) was done using fresco secco.

Unfortunately, Leonardo also experimented with other processes and media as he painted the work and almost immediately it began to dry and flake from the wall. It has been “in restauro”, or under restoration, for many years.

Oil

Oil paint is the most versatile of all the painting mediums. It uses pigment mixed with a binder of linseed oil. Linseed oil can also be used as the vehicle, along with mineral spirits or turpentine. Oil painting was thought to have developed in Europe during the 15th century, but recent research on murals found in Afghani caves show oil based paints were used there as early as the 7th century.

Some of the qualities of oil paint include a wide range of pigment choices, its ability to be thinned down and applied in almost transparent glazes as well as used straight from the tube (without the use of a vehicle), built up in thick layers called impasto (you can see this in many works by Vincent van Gogh). One drawback to the use of impasto is that over time the body of the paint can split, leaving networks of cracks along the thickest parts of the painting. Because oil paint dries slower than other mediums, it can be blended on the support surface with meticulous detail. This extended working time also allows for adjustments and changes to be made without having to scrape off sections of dried paint.

In Jan Brueghel the Elder’s still life oil painting you can see many of the qualities mentioned above. The richness of the paint itself is evident in both the resonant lights and inky dark colors of the work. The working of the paint allows for many different effects to be created, from the softness of the flower petals to the reflection on the vase and the many visual textures in between.

Richard Diebenkorn’s Cityscape #1 from 1963 shows how the artist uses oil paint in a more fluid, expressive manner. He thins down the medium to obtain a quality and gesture that reflects the sunny, breezy atmosphere of a California morning. Diebenkorn used layers of oil paint, one over the other, to let the under painting show through and a flat, more geometric space that blurs the line between realism and abstraction.

Rembrandt was a master of paint-handling, and made more self-portraits than practically any other artist in history. This painting from around 1662 shows the technique of impasto used to build up a wrinkled and cratered surface that suggests the weathered skin of the artist in old age.

The Abstract Expressionist painters pushed the limits of what oil paint could do. Their focus was in the act of painting as much as it was about the subject matter. Indeed, for many of them there was no distinction between the two. The work of Willem de Kooning leaves a record of oil paint being brushed, dripped, scraped and wiped away all in a frenzy of creative activity.

Acrylic

Acrylic paint became commercially available in the 1950’s as an alternative to oils. Pigment is suspended in an acrylic polymer emulsion binder and uses water as the vehicle. The acrylic polymer has characteristics like rubber or plastic. Acrylic paints offer the body, color resonance and durability of oils without the expense, mess and toxicity issues of using heavy solvents to mix them. One major difference is the relatively fast drying time of acrylics. They are water soluble, but once dry become impervious to water or other solvents. Moreover, acrylic paints adhere to many different surfaces and are extremely durable. Acrylic impastos will not crack or yellow over time as oils sometimes do.

Beatriz Milhaze is a Brazilian artist who uses the unique properties of acrylic to create her intricate patterned surfaces. She paints a design on a sheet of plastic and presses it to a canvas which may already contain other painted areas or designs. When it has dried she peels away the plastic sheet leaving the acrylic form attached to the canvas.

Mixed Media

Portland artist Troy Mathews uses latex paint, acrylic paint, and welding crayon on an unstretched drop cloth in this painting of St. Louis Cardinal’s pitcher Bob Gibson from 2016.

The painting is titled The Black Body Problem, a scientific term that refers to objects that absorb light without reflecting light back. German theoretical physicist Max Planck in ca. 1900 created a theory regarding “black-body radiation.” His work was useful to Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity. Mathews uses the term to refer to America’s “black-body problem” of race. Gibson played from 1959-1975 and was a nine-time All-Star, Two-time world Series champion and was awarded two Cy Young Awards during the era of the Civil Rights Movement.

He was also subjected to discrimination by rival teams, fans, and some of his own team-members during his career. Mathews uses opaque paint media that tend to absorb light on a porous support – the canvas drop cloth – that also absorbs paint. His figure captures the dynamic energy of the athlete just after the pitch and the determination that the historical figure exhibited in confronting his social circumstances. Contemporary artists use various media to deepen the meaning of the images and subjects they represent, and Mathews’ painting is a good example of how that works. See more of Mathews’ work at https://www.hyperaccumulator.com/the-black-body-problem

Watercolor

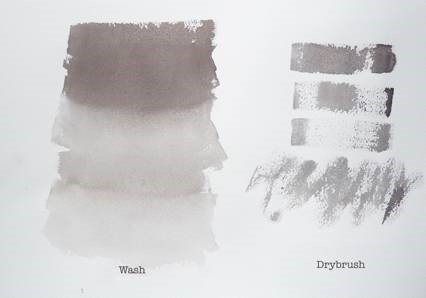

Watercolor is the most sensitive of the painting mediums. It reacts to the lightest touch of the artist and can become an over-worked mess in a moment. There are two kinds of watercolor media: transparent, and opaque or gouache. Transparent watercolor operates in a reverse relationship to the other painting mediums. It is traditionally applied to a paper support, and relies on the whiteness of the paper to reflect light back through the applied color (see below), whereas opaque paints (including gouache) reflect light off the skin of the paint itself. Watercolor consists of pigment and a binder of gum arabic, a water-soluble compound made from the sap of the acacia tree. It dissolves easily in water. There is no white watercolor, but white gouache can be used to add highlights if necessary. Using the white ground of the paper is preferable.

Watercolor paintings hold a sense of immediacy. The medium is extremely portable and excellent for small format paintings. The paper used for watercolor is generally of two types: hot pressed, which gives a smoother texture, and cold pressed, which results in a rougher texture. Transparent watercolor techniques include the use of wash; an area of color applied with a brush and diluted with water to let it flow across the paper. Wet-in-wet painting allows colors to flow and drift into each other, creating soft transitions between them. Dry brush painting uses little water and lets the brush run across the top ridges of the paper, resulting in a broken line of color and lots of visual texture.

Examples of watercolor painting techniques: below, a painting done in the wash technique by John Marin. The Cezanne is created with more dry brush effects.

John Marin’s Brooklyn Bridge (1912) shows extensive use of wash. He renders the massive bridge almost invisible except for the support towers at both sides of the painting. Even the Manhattan skyline becomes enveloped in the misty, abstract shapes created by washes of color.

Self-portrait by French painter Paul Cezanne builds form through nuanced colors and tones. The way the watercolor is laid onto the paper reflects a sensitivity and deliberation common in Cezanne’s paintings. The more planar areas of color and tone creates distinct shapes and can be done on dryer surfaces.

Opaque watercolor, also called gouache, differs from transparent watercolor in that the particles are larger, the ratio of pigment to water is much higher, and an additional, inert, white pigment such as chalk is also present. Because of this, gouache paint gives stronger color than transparent watercolor, although it tends to dry to a slightly lighter tone than when it is applied. Gouache paint doesn’t hold up well as impasto, tending to crack and fall away from the surface. It holds up well in thinner applications and often is used to cover large areas with color. Like transparent watercolor, dried gouache paint will become soluble again in water.

Jacob Lawrence’s paintings use gouache to set the design of the composition. Large areas of color – including the complements blue and orange, dominate the figurative shapes in the foreground, while olive greens and neutral tones animate the background with smaller shapes depicting tools, benches and tables. The characteristics of gouache make it difficult to be used in areas of fine detail.

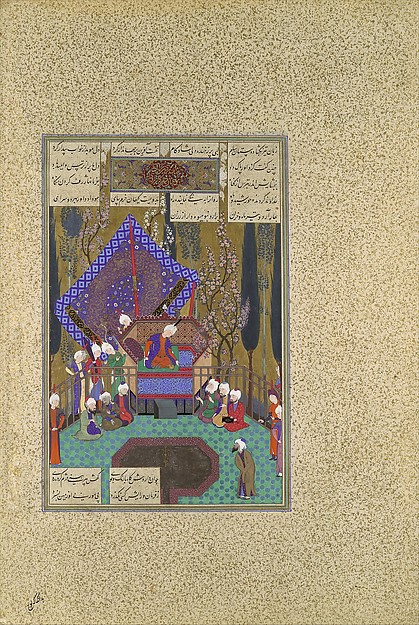

Gouache is a medium in traditional painting from other cultures too. ZalConsults the Magi, part of an illuminated manuscript form 16th century Iran, uses bright colors of gouache along with ink, silver and gold to construct a vibrant composition full of intricate patterns and contrasts. Ink is used to create lyrical calligraphic passages at the top and bottom of the work.

Other Painting Mediums

Enamel paints form hard skins typically with a high-gloss finish. They use heavy solvents and are extremely durable.

Powder coat paints differ from conventional paints in that they do not require a solvent to keep the pigment and binder parts in suspension. They are applied to a surface as a powder then cured with heat to form a tough skin that is stronger than most other paints. Powder coats are applied mostly to metal surfaces and are often seen in automotive or furniture contexts.

Epoxy paints are polymers, created mixing pigment with two different chemicals: a resin and a hardener. The chemical reaction between the two creates heat that bonds them together. Epoxy paints, like powder coats and enamel, are extremely durable in both indoor and outdoor conditions.

These industrial-grade paints are used in sign painting, marine environments and aircraft painting among other uses.

Painting Beyond Painting

Historically other mediums have served the same purpose as painting in religious contexts and in the courts of nobility. Two of those are mosaics and tapestries.

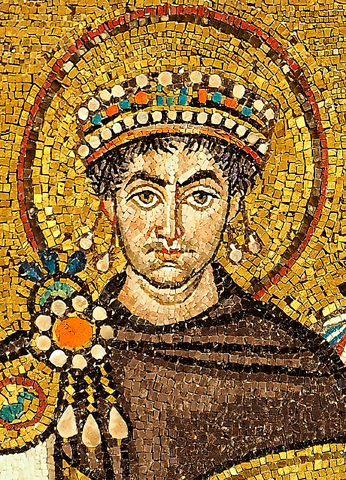

Mosaic

The Greeks and Romans used mosaics to decorate the floors of their homes and basilicas. Intricate designs made of small, individual bits of stone or glass called tesserae were embedded in plaster, mortar or cement. Later Byzantine churches were richly ornamented with tesserae fashioned from small bits of marble, stone, or glass with gold leaf sandwiched between the layers. During the Renaissance artists like Ghirlandaio and Raphael also designed mosaics, but the work was most likely carried out by their workshop artists. Fresco proved to be a faster and less costly form of wall decoration from that period forward, although mosaics continue to be made today.

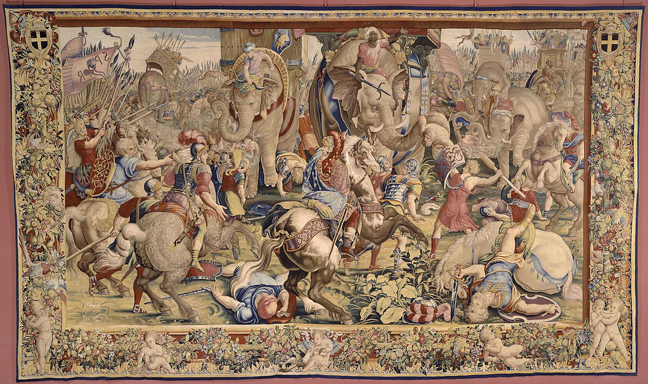

Tapestry

These fabric wall-hangings in Europe rivaled paintings in detail and preciousness. They were, in addition, practical in that they kept some drafts out of old castle walls. Many important artists have created the cartoons – or preliminary drawings/designs – for tapestries including Raphael, Goya, and Charles le Brun. Tapestries were often exchanged between kings as tokens of good will. There were royal tapestry factories like the Gobelins in France where the work was woven by hand with wool, silk, and precious metal-wrapped thread.

Some artists today still work in tapestry or other fiber arts, but now a loom is more likely to be programmed digitally to produce the object. Many other examples of fiber art can be found. Traditionally dismissed as “women’s craft”, works made of woven, tied, crocheted, or other processes are now a major and respected part of art-making.

In front of the NuEdge gallery in Montréal, Polish artist Olek creates a crocheted cover for an existing sculpture turning it into a colorful hybrid.

© Saylor Academy 2010-2017 except as otherwise noted. Excluding course final exams, content authored by Saylor Academy is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license. Third-party materials are the copyright of their respective owners and shared under various licenses. See detailed licensing information.

© Saylor Academy 2010-2017 except as otherwise noted. Excluding course final exams, content authored by Saylor Academy is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license. Third-party materials are the copyright of their respective owners and shared under various licenses. See detailed licensing information.

Saylor Academy and Saylor.org® are trade names of the Constitution Foundation, a 501(c)(3) organization through which our educational activities are conducted.