1.1: Overview of Woman Artists

- Page ID

- 134959

Introduction

"Art is an essential element in the social thread of humanity; it provides the vocabulary for a social construction of culture, and thus should also reflect the unique lenses of women artists."[1] Art history is pivotal in fostering a strong cultural foundation and honing students' critical analysis skills. By examining art throughout history and considering the cultural and societal influences of the time, students can gain a deeper appreciation for its beauty. However, comprehending art can be challenging without understanding the culture. That is why learning about art history is vital in helping students comprehend contemporary art and its significance in today's world while building their understanding of art's relationship with culture. The student population in the community colleges of California comprises many diverse and exceptional individuals. Each student possesses unique abilities, appearances, classifications, and opportunities. This is especially true in the study of art history, where students aim to seek cultural validation through their own individual perspectives. It's worth noting that the community college student population is diverse, guaranteeing that each person's experience is distinct and one-of-a-kind.

The traditional male European perspective of art was considered the mainstream view of what constituted "good art" according to the textbooks used. However, the validity of confining art to Europe and traditional European-American perspectives, does not allow students to relate and appreciate art that reflected their own experiences. Additionally, the lack of representation for female students, who are generally half of any class, is evident in art textbooks. A more diverse and inclusive curriculum showcasing a wider range of perspectives and experiences in the art world is required in today’s curriculum.

The textbooks used in our community colleges in California predominantly showcase art from a European/American male perspective, which may not be relatable to our diverse student population. The term 'androcentrism' stems from ancient Greek and refers to the practice of placing male human beings or masculine opinions at the center of one's worldview. This includes ignoring women's history and the cultural art created by women. Charlotte Gilman first brought this issue to light in her book, The Man-Made World, or, Our Androcentric Culture (1914). According to her, androcentrism can be “understood as a societal fixation on masculinity, where male life patterns and mindsets are considered universal, while female ones are viewed as deviant.”[2] Sadly, this results in the exclusion of women and cultural art from students' homeland in the textbooks. This makes it challenging for students to engage with the material presented in the classroom. Students of color, non-European-American cultures, and women are underrepresented in the art that is presented as "great" and used for learning and appreciation. Female students expect equal representation in their textbooks, given the progress made through the women's movement.

Where Were the Women

Our current beliefs and cultural perspectives influence the way we see historical art and culture. It's important to note that Western paradigms have roots in ancient Greece and Rome, where male artists dominated and focused on themes of mythology, rulership, and warfare. Women were often portrayed in subordinate roles, except for goddesses. Additionally, classical times were marked by xenophobic attitudes towards outsiders, which is reflected in the way they described "others" in art.

The belief in the exceptionalism of Classical philosophy and art still holds sway in various aspects of contemporary Western culture. This mindset has undoubtedly significantly impacted the study of art history. However, social justice movements such as civil rights and feminism have brought these issues to the forefront in the past century. Women's groups, Native Americans, and minority communities have exerted pressure on art historians to scrutinize the fundamental principles of aesthetic criteria that were established primarily by white men from an affluent 18th-century European-American society. Although there has been a growing awareness of the inequalities and changing attitudes, bringing about changes in the content of art history courses has been a slow and challenging process.

It's puzzling to note the absence of women in the art world. Were they intentionally excluded, or was there simply a lack of female artists to include? In 1971, Linda Nochlin addressed this issue in her article "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?" She concluded that the absence of great female artists is not due to any inherent inability on the part of women, but rather because they were not given the same opportunities as men. Nochlin's arguments primarily focus on European art from the Renaissance to the 19th century.[3] During the 16th and 17th centuries, most women were not allowed to draw or paint from nude models, which prevented them from attempting large-scale biblical allegorical paintings. Women were also excluded from the French Salons in the 18th century, limiting their exposure to the art world.

In the 19th century, some female artists made a breakthrough in the French art scene, but many of them were daughters of artist fathers or other relatives. The textbooks used in art history courses often reinforce the idea that the core representations of art are consistent because they feature the greatest works of art from Europe and America. However, these representations are not always accurate, as they are written from a purely Eurocentric point of view. The 21st-century art history textbooks have evolved over time, starting with Helen Gardner's 1926 first edition of an illustrated art history textbook, which is still widely used in North American colleges today. Gardner's textbook emphasized the importance of the Renaissance as the high watermark of Renaissance humanism, a revival of classical Greek and Roman art, almost all focused on a Euro-centric bias.

Overcoming Obstacles

Throughout history, female artists have made remarkable contributions to the art world, but their works have frequently been disregarded or undervalued in comparison to those of their male peers. From the Renaissance era to present times, women have defied societal norms and limitations by producing compelling and thought-provoking art that reflects their unique experiences and perspectives. Despite encountering obstacles such as limited access to education and career opportunities, as well as prejudice and discrimination, women have persisted and left a significant impact on the art world. Women artists have continually encountered numerous challenges in pursuing a Career in the Arts including:

- Societal and cultural attitudes have prioritized men, limiting women's access to education and training in the arts.

- Traditional gender roles have relegated women to homemaking and caretaking, restricting their opportunities for education and professional development.

- Discrimination based on gender has also hindered women's access to educational institutions and formal training in the arts.

- Financial barriers have limited the educational opportunities of women, especially those from marginalized communities.

- The lack of female role models in the arts has also made it difficult for women to envision a career in this field and pursue educational opportunities.

- Many forms of women’s art is characterized as “crafts” and not art.

- Career advancement: Women artists have faced challenges in advancing their careers and securing exhibitions, representation, and recognition due to gender-based discrimination and unequal pay.

- Lack of representation: Women artists have been historically underrepresented in the art canon and exhibitions, impacting their visibility and recognition.

Although women have faced numerous challenges, they have made remarkable strides in recent years, gaining better access to education and training in the arts. Nevertheless, it remains imperative to strive towards creating equal opportunities and resources for women to pursue their artistic aspirations. Throughout history, prejudice and discrimination have posed significant obstacles for women artists. Throughout history, cultural attitudes have greatly influenced the experiences of women artists. One of the most significant perspectives that has affected women is the belief in male artistic superiority. Women artists have had to challenge cultural attitudes that promote this notion and restrict recognition and opportunities for women. Gender roles have traditionally confined women to specific roles, but women artists have worked to broaden cultural perspectives on subject matter and style in art. Unfortunately, limited viewpoints and cultural stereotypes about women's artistic abilities have hindered their reception and opportunities for advancement. However, as more women's art is celebrated and acknowledged, cultural attitudes are gradually evolving towards a more inclusive and diverse art canon that values women's perspectives and experiences. The exclusion of women artists from the Art History Textbooks is often due to a combination of factors such as:

- Patriarchy and gender bias in the art world and academic institutions

- Lack of recognition and promotion of women's work

- Historical bias toward male artists and their work

- Limited access to artistic training and resources for women

- Difficulty in tracking the provenance of works created by women

- Unconscious or implicit biases in the curation and preservation of art collections

The representation of female artists in art history has been significantly lacking due to various factors. However, there has been a commendable effort in recent times to rectify this imbalance and bring to light the invaluable contributions of women artists. Women artists have been subjected to discrimination and gender bias throughout history, resulting in their work being undervalued and overlooked. They have faced restricted educational and professional opportunities, unequal pay and recognition, gender-based limitations on subject matter and style, and cultural attitudes that promote male artistic superiority. The exclusion and underrepresentation of women in the art world have reinforced the idea that their contributions are inferior, making it challenging for future generations of female artists to gain recognition and visibility. Despite the progress made in recent years, the systemic bias still exists. Nevertheless, efforts are underway to address this imbalance and give women artists the acknowledgement they rightly deserve.

In recent years, there has been a growing movement among art history scholars to broaden the scope of the traditional canon by incorporating more works by women and minority artists. Unfortunately, this effort has not always been successful, as evidenced by the shortcomings of the 1980 edition of Gardner's textbook. While this edition did feature several female artists, including Artemisia Gentileschi, it failed to fully recognize and appreciate their contributions to the field. Specifically, the depiction of Gentileschi's Judith and Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes fell short of what it could have been. Instead of focusing on the artist's impressive technical skills and unique perspective, the text chose to emphasize her tragic personal life. This approach perpetuated the long-standing disregard for women's contributions to art history, reinforcing the dominant (white, male) Euro-American perspective that has long shaped the field. This narrow perspective is a reflection of broader societal biases and limitations, and it impedes efforts to create a more inclusive and diverse art history curriculum. To truly engage and educate today's diverse student population, it is essential to recognize and address the sociocultural filters through which information is presented and interpreted. By doing so, we can begin to create a more equitable and representative art history education for all.

To truly comprehend the written history of women artists in art history textbooks, it is imperative to investigate the sources of the information. In Vasari's (1568), The Lives of the Artists, a book about the lives of the Renaissance artists, none of the artists mentioned were women. The Renaissance was "a re-birth" from a feudal system, and "women of every class saw a change in their social and political options that men did not."[4] Women were controlled by their parents until they were handed over in marriage to their husbands, where the men continued dominance, continuing into the 20thcentury.

Throughout the Renaissance era until the 19th century, there was a prevalent trend where male artists would take credit for works that were actually created by female artists. This practice was so widespread that some male artists even went to the extent of signing their names to paintings that were not their own. In 1890, Judith Leyster's painting titled Happy Couple which was on display at the Louvre Museum was rightfully attributed to her, which in turn led to the re-attribution of seven additional paintings. It is worth noting that while Leyster's status as a talented female artist was finally acknowledged, some critics still felt the need to emphasize her gender. This resulted in her paintings being undervalued and priced lower than those created by male artists.

Women’s Movements

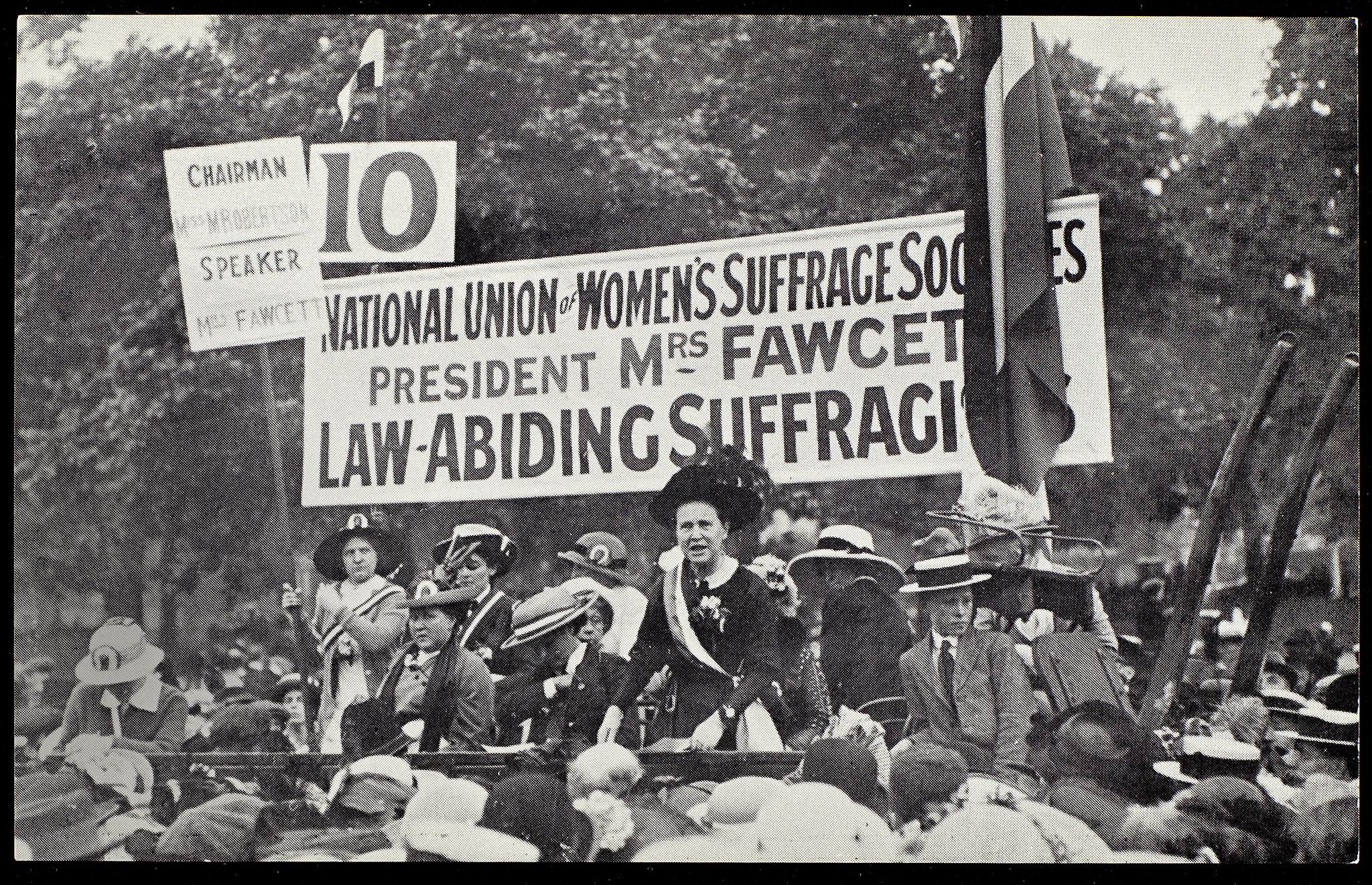

The term "feminism" has its roots in the French word "féminisme," which emerged in the early 1900s and quickly spread across Europe and eventually to the United States. The word is a combination of "femme," meaning woman, and "isme," signifying a social movement. At its core, feminism represents a push for social change and greater equality for women. In the United States, feminism played a significant role in securing women's right to vote in 1920, following decades of activism and advocacy. During this time, women across the globe were organizing and fighting for their rights. The suffrage movement, which aimed to secure voting rights for women, was one of the most widespread and significant social movements of the era. In the United States, the National American Woman Suffrage Association was formed in 1890, and women participated in various forms of activism, such as protests and demonstrations, to draw attention to their cause. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, organizations like the Women's Social and Political Union staged protests and demonstrations to demand the right to vote. Overall, the feminist movement of the early 1900s represented a critical turning point in the fight for gender equality. Through their activism and advocacy, women were able to secure important political and social rights, paving the way for future generations to continue the fight for greater equality and fairness.

During the same time period as the suffrage movement, women were actively involved in various other social reform efforts aimed at enhancing their status. Women from different countries were demanding equal pay for equal work, as they were being unfairly compensated in comparison to men for performing the same job. The labor movement also played a significant role in advocating for better working conditions, such as reducing work hours, better pay, and improved safety standards. Women's access to education and employment opportunities was also a primary concern as they faced significant obstacles. Women's organizations (1.1.2) and activists, driven by the belief that education and employment opportunities were crucial for achieving greater equality, tirelessly worked towards improving these areas for women. Their efforts helped pave the way for women to achieve greater equality in society.

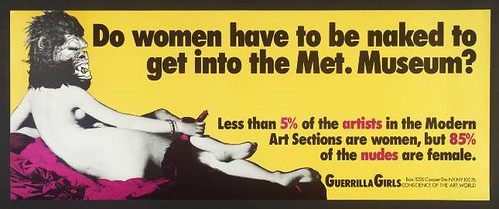

Women's social reform movements gained momentum throughout the 1900s, as women from diverse backgrounds and countries united to demand greater rights and equality. Despite encountering significant opposition, their efforts paid off in many instances, with women securing the right to vote, equal pay for equal work, and improved access to education and employment opportunities. In the United States, the "women's movement" reached a pivotal turning point during the 1960s, expanding into the women's liberation movement. Women were expected to manage both childcare and earning a living, while men only had to focus on earning a living. The women's liberation movement demanded political and economic rights, and expanded women's equality to encompass equal pay for equal work, support with household responsibilities, and equal opportunities. Despite the second wave of feminism, women continued to be marginalized in the public arena, with only 5% of artists in the New York Whitney Museum being female.

Demanding Inclusion

Over the course of the next two decades, significant social changes occurred in relation to women's issues, resulting in increased freedom and opportunity. The Sixties were marked by the emergence of sex, drugs, rock, and roll, as well as the approval of the first oral contraceptive. The Seventies saw the rise of "women's lib," "consciousness-raising," "no-fault" divorce, and Title IX, which ensured equal funding for women's sports. The Feminist Art Movement aimed to bridge contemporary art and women, resulting in a motivated movement that transformed social attitudes and improved gender stereotypes in the arts.

Throughout the course of history, women artists have confronted substantial obstacles as a result of their lack of representation and visibility. Notwithstanding their invaluable contributions to the art world, they have been systematically underrepresented in the canon of art and exhibitions, which has impeded their recognition and visibility. Furthermore, gender-based prejudice and discrimination have restricted their opportunities for representation and visibility in museums, galleries, and art collections. Nevertheless, women artists have demonstrated incredible resilience in the face of adversity, and there are now concerted efforts underway to address and rectify these imbalances. Women's art is steadily gaining recognition, appreciation, and celebration, with their unique experiences and perspectives being incorporated into a more diverse and inclusive art canon.

Women have been instrumental in the creation of art throughout history, despite facing gender discrimination and limited opportunities. Their contributions to the art world are invaluable and deserve to be recognized and celebrated. The history of art has been shaped significantly by women, and including more female artists in art textbooks is a necessary step in addressing the historical imbalance and providing students with a comprehensive understanding of the art world. Promoting gender diversity in this way not only corrects historical imbalances but also encourages students to appreciate and value the contributions of all artists.

In the 1970s, a significant development in the fight for gender equality and women's rights took place in the form of the Women's Liberation March, which comprised a series of protests and demonstrations in the nation's capital, Washington, D.C. This movement was a critical part of the second-wave feminist movement in the United States and focused primarily on issues such as gender equality, reproductive rights, workplace discrimination, and social and cultural norms surrounding women. One of the most notable events in this movement was the Women's Strike for Equality (1.1.3), which took place on August 26, 1970. The march was organized by the National Organization for Women (NOW) and drew around 20,000 participants, including prominent feminist activists such as Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem. The main objective of the march was to bring attention to the various inequalities faced by women and to push for legal and societal changes that would promote women's rights.

The Women's Liberation Marches in the 1970s were characterized by the demand for equal opportunities in education, employment, and politics as the fight against gender-based violence and the push for reproductive freedom. These marches were crucial in raising awareness, challenging traditional gender roles, and mobilizing support for women's rights and gender equality. The activism and advocacy generated by these marches contributed to significant legislative and social changes, such as the passage of Title IX, which prohibits sex-based discrimination in education, and the legalization of abortion with the landmark Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade.

The Women Who Defined Feminist Art

Starting in the 1970s, societal expectations placed the responsibility of raising children and working on women, while men were solely expected to provide financially. The women's liberation movement aimed to secure equal political and economic rights, including equal pay for equal work and access to household assistance and opportunities. Despite the progress made during the second wave of feminism, women remained underrepresented in public spaces, such as the Whitney Museum in New York, where only 5% of the artists were female.[5] Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro created the Womanhouse project at the California Institute of the Arts. The project consisted of 17 rooms of visual representations of gender-stereotyped relationships.

Female artists delved into the realm of women's spaces, employing metaphors to construct extensive installations such as The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago. Chicago's creation featured a large triangular table adorned with genital depictions on ceramic plates, commemorating renowned women from history. In the last 30 years, feminism has created opportunities for female artists regardless of if they are feminists or not (Freedman, 2000). The famous art historian Linda Nochlin published the influential "Why have there been no great female artists?"[6]

"The fault, dear brothers, lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education—education understood to include everything that happens to us from the moment we enter this world of meaningful symbols, signs, and signals. The miracle is, in fact, that given the overwhelming odds against women or blacks, so many of both have managed to achieve so much sheer excellence in hose bailiwicks of white masculine prerogative like science, politics, or the arts."[7]

The Guerrilla Girls, (1.1.4) a group of American women activists, aimed to bring attention to the dominance of white male artists in the art world. In the 1980s, they sought to elevate women artists and artists of color after a New York Museum displayed an international painting and sculpture exhibit featuring only 13 women out of 169 artists. This disparity became their rallying cry to eradicate sexism and racism in the art industry.

The Glass Ceiling

During a feminist conference that took place in 1978, a woman by the name of Marilyn Loden brought forth the concept of the "Glass Ceiling". This term was used to describe the invisible obstacle that prevented women from reaching their career goals in the business world. Although the panelists had been focusing on the deficiencies of women in this regard, Loden was determined to speak out and defend women against the cultural barriers impeding their progress. Rather than accepting the self-deprecating ways in which women were often portrayed, she highlighted the importance of breaking down these barriers to allow women to achieve their full potential. "It seemed to me that there was an invisible barrier to advancement that people didn't recognize," Loden commented to The Washington Post in 2018. Loden described the barrier as the 'Glass Ceiling".[8]

For the past 45 years, the metaphor of the glass ceiling has persisted in women's careers. Despite breaking through this barrier, women still face its effects. The term was coined during the Second Wave of feminism when women started entering traditionally male-dominated industries like politics, corporations, and education. Even though many women climbed up the ladder, reaching the top still seemed impossible. Over time, the glass ceiling has taken on different names such as the 'bamboo ceiling' for Asian Americans, 'stained glass ceiling' for women in the clergy, 'celluloid ceiling' for women in Hollywood, 'marble ceiling' for women in government, and 'perspex ceiling' for women in manufacturing. In the latter part of the 20th century, women started to take on middle management positions, prompting discussions about the severity of this issue.

Feminist Pedagogy

The main theoretical framework for this textbook is Feminist Pedagogy. Feminist pedagogy is based upon the works of Feminist scholars such as Maher and Tetreault (1987) and bell hooks (1994), who support pedagogy addressing gender inequality in classrooms. bell hooks advocated for liberation in the classroom by encouraging students and teachers to transgress and look for collaboration, making education more stimulating and comforting. Feminist pedagogy, according to Maher and Tetreault (1987), is based upon an alternative instructional model informed by human experiences and knowledge construction. They demonstrated that all "human experiences are gendered…they are essentially shaped by our being either men or women and therefore subject to social prescriptions associated with either sex" [9]

Ideally, over time feminist pedagogy can work to transform and foster empowerment in women and thus eradicate oppression. As early as 1978, Maxine Greene wrote, "I am arguing for intensified awareness of women's realities, the shape of their own lived worlds. Not only might this make possible a clear perception of the arbitrariness, the absurdity (as well as the inequity) involved in genderizing such fields as the arts…." As such, most classrooms or curricula may be inadequate for women's needs and lack guidance toward materials and approaches better suited to include and engage women. The classroom can become an active environment, providing positive feedback, shared goals, and a liberatory climate to overcome oppression. A feminist classroom also allows the integration of intensive skills to enhance students' connections to each other and the curriculum.

On January 21, 2017, (1.1.5) The Women's March organized one of American history's largest single-day protests. The day after President Donald Trump's inauguration, five million people marched across the globe, in every state and continent, launching a movement. Prompted by Trump's policy positions and rhetoric, women took to the streets to protest his misogynistic and threatening rights of women. The Women's March has continued yearly, and today, it is disregarded by the overturning of Roe vs. Wade, a statute that allows a woman to decide about abortion.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=865&height=576)

Feminist pedagogy is a philosophy of education that emerged during the second wave of feminism in the 1960s. This wave followed the first wave of feminism, which fought for suffrage. The post-World War II era saw significant changes in society, with women taking on men's jobs, including those of "Rosie the Riveter." Additionally, African Americans, who were sharecroppers in the Deep South, found employment in the North and West. However, Executive Order 9066 resulted in the internment of Japanese American citizens, which disrupted their lives and questioned their loyalty based solely on their heritage. This was a time of great social change, and feminist pedagogy emerged as a response to the need for education that reflected these changes.

In terms of women's issues, the next twenty years brought about significant social changes that aimed towards greater freedom and opportunity. The 1960s saw a cultural revolution with the rise of sex, drugs, and rock and roll, as well as the legalization of the first oral contraceptive. The 1970s brought about the women's liberation movement, consciousness-raising efforts, the advent of "no-fault" divorce, and equal funding for women's sports, known as Title IX. These changes also brought about an awareness of the limitations of traditional teaching methods, which failed to address women's educational needs. Feminist scholars like Gloria Joseph (1981) and bell hooks (1994) advocated for pedagogy that addressed gender-based inequalities, ultimately leading to the establishment of women's studies programs in universities. The goal of feminist pedagogy is to empower women and eliminate oppression over time.

Feminist pedagogy is a vision of what education can look like and how it can better serve students. "Knowledge that is relevant to the student's own life becomes readily accessible in contrast to the 'distance' created by the larger-than-the-life greatness of [mostly male] geniuses and authorities"[10] . In other words, when students—in this case, women's—experiences are absent from the classroom, they cannot as readily identify with the meaning and content of what they are supposed to learn. When students can connect their experiences to what they are learning—seeing themselves or those like them reflected in the course materials—they are more likely to develop their own "voices" and feel they belong in this world.

The use of textbooks in classrooms has long been a challenge to gender equality, and this is especially true in the realm of art history. In order to create a truly inclusive classroom environment, investment in social change is absolutely necessary. Furthermore, educators must take a hard look at the curriculum and content they are presenting to their students. It is essential for women's voices from diverse backgrounds and all walks of life to be incorporated into the classroom in order to provide students with multiple perspectives to analyze the issues they face in their daily lives. Only by doing so can we prevent the erasure of women's contributions to the art world. By recognizing and celebrating women's achievements in the art industry, we can also help to create a more inclusive and accurate comprehension of art history. This acknowledgment will inspire and empower future generations of women artists, resulting in a diverse and vibrant artistic landscape. Ultimately, it is only by taking a proactive and intentional approach to promote gender equality in the classroom and beyond that we can hope to create a truly just and equitable society.

Teachers have the ability to make informed curriculum decisions that greatly benefit their students when they utilize a robust feminist pedagogy. This approach fosters collaboration among students, which in turn elevates their level of understanding and comprehension. The resulting collaborative learning experience, when combined with the desired learning outcomes of the curriculum, opens up new avenues for personal growth and development. By embracing feminist pedagogy, teachers are creating a dynamic and inclusive learning environment that empowers their students to achieve their full potential.

Those Are My People

Art brings people together and has been since the beginning of time. It also has allowed civilizations and cultures to showcase who they are and help them identify with each other. A student once exclaimed: "those are my people," as she read through the art textbook and discovered she recognized herself and her culture in a textbook for the first time. For students from a diverse ethnic background, it is important to alter the way art history is taught and written. By prioritizing gender and cultural equity, art history can reflect a more accurate representation of the world.

This textbook on art history aims to broaden the traditional European-Western perspective by promoting inclusivity, diversity, and equity. It offers a culturally responsive overview of art that includes voices beyond the usual coverage of European art. This textbook explores the interconnections between different societies across time, centuries, and geographic regions, providing a comprehensive understanding of how female artists created art in their time period and their relationships with cultures and history.

Many individuals have a keen interest in studying the history of female artists and their evolution over time. However, historical perspectives tend to be predominantly European-centric, often disregarding the sophistication of other continents. In the past, encyclopedias were the primary source for knowledge about ancient times and far-off locations. Now, the field of art and art history and women’s position in history has expanded beyond traditional drawing and painting to encompass a variety of mediums. For example, the use of ceramic wheels and kilns has been a practice for over 100,000 years, teaching us how to craft pottery. Similarly, ancient techniques like mixing pigment with water to create desired consistency are still relevant today. Modern graphic design classes demonstrate the longevity and effectiveness of marketing and propaganda tactics over thousands of years. Sculpting with different materials has helped us understand the challenges of lost cast molding techniques, particularly when working with bronze. Women throughout time worked with different medium even if their work was not documented or acknowledged.

In the present day, most textbooks on art history are not very engaging and can be confusing. A new approach was necessary to teach art history, one that would be inclusive of more women while still supporting the chronological sequence of historical learning. Such a limited perspective does not cater to the diverse student population in California. Herstory: Women Artists in Art History is an innovative textbook that offers a more diverse perspective on how female artists integrated into history. Each chapter is structured around a specific time period, with a section dedicated to different cultural art or movements that occurred concurrently. The book highlights the work of female artists who are often overlooked in traditional art history textbooks.

[1] Casey, B. (2016). (Women) Artists and the Gender Gap (Museum). University of Nebraska.

[2] Gillman, C. (1914). The man-made world: Our androcentric culture. New York, NY:

[3] Nochlin, L. (2015). Female artists. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson.

[4] Freedman, E. (2001). No turning back: The history of feminism and the future of women. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. (p. 319).

[5] Freedman, E. (2001). No turning back: The history of feminism and the future of women. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. (p. 319).

[6] Nochlin, L. (2015). Female artists. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson.

[7] Nochlin, L. (2015). Female artists. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson.

[8] Vargas, T. (2017). She coined the term 'glass ceiling.' She fears it will outlive her. Washington Post. 12(13). Retrieved from: By Theresa Vargas

[9] Maher, F., & Tetreault, M. (1987). The feminist classroom: Dynamics of gender, race, and privilege. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers

[10] Sandell, R. (1991). The liberating relevance of feminist pedagogy. Studies in Art Education. 32(3), 178-187.