8.4: Minimalism (1960 – early 1970)

- Page ID

- 209576

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

Minimalism became one of the basic art forms during the 1960s, using primary and sleek geometric contours without decorative embellishments. The movement started in New York with young artists challenging the boundaries of traditional media, perceived emotions, and overt symbolism. The artists reflected the socioeconomic issues of the 1960s and rejected the establishment and formal hierarchies. By the 1970s, the movement spread across the United States and Europe, and artists used industrial materials, changing the concept of sculptures and painting. They created pure objective elements of simplistic shapes made from commercial materials.

Minimalist artists seldom used traditional materials; instead, they incorporated methodologies found in commercial manufacturing and fabrication. Using abstracted construction removed the artists' emotion, expression, and feelings found in brushstrokes, patterns, or color. Generally, the artists used house paint, cement, or fiberglass instead of oil paint, canvas, or clay. A part of Minimalism was to incorporate the contiguous space into their artwork and bring the viewer into the space through multiple points of view. Industrial materials allowed artists to integrate weight, light, size, or even gravity characteristics.

The Minimalist sculptors were a significant part of the movement and created three-dimensional forms using fiberglass, plywood, plastic, sheet metal, and aluminum.[1] Sculptures were no longer elevated on platforms and sat directly on the floor with repetitive geometric shapes. Minimalist painters used geometric forms in repeated patterns and specific horizontal and vertical lines to delineate space. Some artists worked with light, using fluorescent tubes to form patterns of color and shapes. They focused on how light affected the perception of the viewer's concept of shapes formulated by light.

- Agnes Martin (1912-2004)

- Eva Hesse (1936-1970)

- Carmen Herrera (1915-)

- Anne Truitt (1921-2004)

- Rosemarie Castoro (1939-2015)

- Charlotte Posenenske (1930-1985)

- Jo Baer (1929-)

- Nasreen Mohamedi (1937-1990)

- Beverly Pepper (1922-2020)

Agnes Martin

Agnes Martin (1912-2004) was born in Canada and lived in Vancouver during childhood. She went to college in Washington, received a bachelor's degree in education, and moved to New York City. Martin became interested in modern art and took several classes before attending the University of New Mexico, followed by earning a master's degree in art at Columbia University. 1957 she moved back to New York to a local art community. Martin struggled with mental illness, including electric shock treatment. In 1967, she disappeared from New York and spent time crossing the United States and Canada, camping in different places. Martin finally settled in New Mexico, where she built her home and studio and eventually began to paint again.

Martin's work strongly resembles the rural and desert landscape she found in Canada's vast plains and New Mexico's dry, scrubby desert. Her palette was relatively monochromatic and unadorned. Martin destroyed her early works before adopting pure abstraction and Minimalist form. She focused on lines and grids with soft, subtle colors. Martin used mathematically divided lines, a regularity found in her work. Some lines were thin and pencil-like; others were wider and more painterly. Her addition of muted color gave her work the reflection of her beliefs in Eastern philosophy and timelessness. Martin's works were generally based on one concept with variations. She wanted them to convey a broad range of emotions and experiences to the viewers. Art reviewers consider her work in totality, with quiet contemplation of the relationships of the fine lines and soft colors.

In her painting, White Flower (8.4.1), Martin explained how the image was about a mental understanding, not the concept of an actual white flower. She wanted people to react to the painting like the organic flower. The grid was made from white horizontal and vertical lines shaped into rectangles. Inside the small rectangles were proportioned white dashes resembling fabric. The actual white flowers she contemplated were based on the small white flowers with edible berries growing on the plains of Canada. Untitled #12 (8.4.2) displays a graphite grid against the light background. Many art historians view the image as one of her more spiritual works and a balance between sensual and austere. Martin remarked, "Work like mine describes the subtle emotions that are beyond words, like music."[2]

In Untitled #14 (8.4.3), Martin used ink, pencil, and paint, multiple types of material, a common thing she frequently included in her work. Using numerous materials, Martin obtained different looks in each of her paintings. In #14, she applied gesso on the canvas before adding the lines and color, building a distinctive texture. The darker line against the light gray background demonstrated her use of the signature grid pattern. Martin used this essential grid and varied it with texture, width between lines, color, or materials. Although Minimalism relied on a more rigid formula of lines, Martin's grid use was not systematic, only coordination of lines from space to space.

Agnes Martin’s restrained yet evocative paintings came from her belief that spiritual inspiration rather than intellect created great work. In this film, which features rare archive footage of the artist in her studio in New Mexico, her art dealer and confidant, Arne Glimcher, remembers Martin’s philosophical ideas about her work and her rigorous process in developing her paintings.

Eva Hesse

Eva Hesse (1936-1970) succeeded as an artist despite a difficult life. She was born in Germany to a Jewish family in 1936. The family tried to leave Germany as the war started and sent Hesse and her sibling on one of the last Kindertransport trains. The trains were loaded with small children bound for the Netherlands to escape the brutal roundup by the Nazis. Her parents escaped six months later, and the family emigrated to New York. After World War II, her parents divorced, and her mother committed suicide. Hesse attended Yale University, graduating with a bachelor's degree. After college, she returned to New York and worked with some other new Minimalist artists. Hesse was married for a few years before she divorced. In 1969, she developed a brain tumor, had multiple unsuccessful operations, and died at 34. However, Hesse's short artistic career was very successful.

Hesse worked with three-dimensional and industrial materials, primarily focusing on latex and fiberglass because latex could be molded, cast, and hardened. Hesse belonged to a group experimenting with new synthetic materials and even invented her method of rubberizing fabric. Her sculptures were usually grouped or placed in a grid-like formation, minimally based on simple formations and a reduced color palette. The works were generally wrapped, wound, or threaded. Hesse's work was abstract, frequently referring to male or female bodies, contradictory illusions, or interpretations.

Untitled (8.4.4) changed the rigid straight lines used by Minimalist artists to irregular, softer organic lines. Hesse knotted different pieces of rope together and soaked them in liquid latex. She assembled the parts into a sculpture of twisted, arching lines when the rope hardened. The work is attached to the ceiling and wall, flexible enough to support variable installations. Hesse wrote in her conceptual drawing of the work, "hung irregularly tying knots as connections letting it go as it will. Allowing it to determine more of the way it completes itself."[3] Repetition Nineteen III (8.4.5) is an installation of nineteen round, translucent forms shaped like a bucket. The forms are twenty inches high and hand-formed instead of manufactured, so they are irregular and can be arranged in any formation. Hesse used fiberglass and resin, two materials that tend to discolor or deteriorate over time, a phenomenon in her work today. She always said, "Life doesn't last; art doesn't last. It doesn't matter." [4]

Hang Up (8.4.6) was made in 1966 when Hesse decided to stop painting and concentrate on sculptural works. She wrapped the blank canvas made from bed sheets on a frame and added an excessively long tube made from steel and covered with a cord to protrude into the viewer's space. Hesse thought this image was one of her most important because it was absurd, blurring the line between paintings and sculptures. Hesse's work, Not Yet (8.4.7), reflected her desire to create forms interpreted as almost human parts, however just an erotic resemblance. She used cotton netting and plastic drop cloths to make the image, materials found in any artist's studio. Hesse used repetitive forms like the Minimalists. However, she used forms that were uneven and irregular. Instead of manufactured materials, she handmade her shapes. Historians often explain Hesse's work as reflecting her anxieties from a painful childhood.

Eva Hesse, Untitled (Seven Poles), aluminum wire, fiberglass, and resin, 1970, variable dimensions.

Carmen Herrera

Carmen Herrera (1915-2022) was born in Havana, Cuba, one of seven children. Her father was part of the Cuban intellectual elite, a captain in the army liberating Cuba from Spain. Her mother was an author and journalist. Herrera had private art education when she was young, even attending school in Paris at fourteen. She studied architecture at the Universidad de la Habana for one year, quitting because of the continual fighting in the streets and the unstable ability of the university to remain open. Herrera married a teacher from New York and moved there. She studied art before moving to Paris. Refining her art, Herrera focused on her straight-line, hard-edge style, a technique she developed similar to Ellsworth Kelly, who lived in Paris during the same period. When she returned to New York, she continued to face rejection as an artist, a problem Herrera attributed to prejudice against women. She was not allowed to exhibit at one gallery because she was female and received little recognition until the 2000s. She did not sell a painting until she was eighty-nine and did not attain acknowledgment until 2009, when a large exhibition of her work was held in the United Kingdom.

Herrera's architectural training influenced her concepts and focused on lines and color within the lines, a limited color palette, and simplistic geometric shapes. She developed a process of painting she still used today. She started by drawing a concept and then recreated the idea on vellum, where she added colors with paint markers. On the final canvas, Herrera marked her lines with tape before applying layers of paint. "I like straight lines; I like angles; I like order. In this chaos that we live in, I like to put order. I guess that's why I am a hard-edged painter, a geometric painter"[5] Untitled (8.4.8) was one of her breakthrough paintings, establishing her style and gaining recognition. She also asserted her love for straight lines. The painting looks like a W; however, she changed the lines by reversing the black and white colors on the four panels to create the visual effect.

The painting Amarillo Dos (8.4.9) is a stunning example of the masterful use of the interplay between line and color to convey a sense of movement. Even though there is a visible tilt in two distinct parts of the painting, the top and bottom sections remain level. The artist, Herrera, has ingeniously used the bold yet vibrant yellow color and a symmetrical yet asymmetrical image to create a feeling of instability. Similarly, in Green and White (8.4.10), we see clever use of irregular shapes that do not entirely fit together, with the white sections generating different spatial balance in the negative space. Herrera employed a bold and contrasting color to enhance the sense of imbalance and create visual tension. It is worth noting that Herrera's innovative body of work was created during the 1960s and 1970s, when her work could have been more appreciated, and the artist was only recently recognized as a woman ahead of her time. The mesmerizing artwork of Herrera is a testament to her artistic genius and her ability to create a dynamic visual language that challenges the viewers' perception of balance and movement.

Carmen Herrera was born in Havana, Cuba, in 1915. She moved frequently between France and Cuba throughout the 1930s and 1940s; having started studying architecture at the Universidad de La Habana, Havana, Cuba (1938–39), she trained at the Art Students League, New York, NY, USA (1942–43), before exhibiting five times at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, France (1949–53). She settled in New York in 1954, where she continues to live and work.

Anne Truitt

Anne Truitt (1921-2004) was born in Maryland before moving to North Carolina as a teenager. In college, she pursued a degree in psychology and graduated from Bryn Mawr College in 1943 before working in a hospital psychiatric ward. By the late 1940s, she decided to change careers and enrolled in art classes at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Washington, D. C. She married James Truitt in 1947 until 1971, when they were divorced. Truitt started her art career with figurative sculptures. At a museum, she encountered Barnett Newman's work and was inspired by the simplicity and subtlety of color modulation, a turning point for her career. Truitt's first sculptures were made of wood based on forms of memories of fences in her childhood. Her sculptures were created from wood and then painted with multiple layers of acrylic in monochromatic color. The sculptures were usually hollow and weighted to maintain their positions. Her painting process was extensive and time-consuming; the first layer was gesso, followed by multiple layers of paint, sometimes over thirty layers. Truitt was careful with her brushstrokes; each application of paint alternated between horizontal and vertical, each layer sanded to achieve a purity of color and finish. Truitt also created a large set of pencil and ink drawings, wrote books, and taught at the University of Maryland.

Truitt's art installation, In The Tower (8.4.11), was a stunning display of color. The piece featured a wide range of hues, from bold reds and blacks to lighter shades of yellow and lavender. What made Truitt's approach unique was her use of mixed colors, carefully applied based on their opacity and translucency. She believed certain base colors could bring out the best in the top colors, giving them a sense of vibrancy and perfection. The columns in the installation were each different in color and height, making for a truly captivating experience. In another work, Green: Five (8.4.12), Truitt shifted from acrylic to oil-based enamel on wood. The result was a tower that appeared black, but only after multiple layers were applied to achieve the desired final color. Truitt's attention to detail and careful selection of materials made for an awe-inspiring display of artistry and skill. She mainly used yellow, scarlet, lavender, light blue, black and white, believing colors were organic and living, creating a feeling of "aliveness" in the colors.[6]

Renowned American artist and writer Anne Truitt reads a selection from her recently republished journal, DAYBOOK, discussing how her work takes form.

Rosemarie Castoro

Rosemarie Castoro (1939-2015) was born in Brooklyn, New York, and lived in New York all her life. She attended Pratt Institute and experimented with dance and choreography. Castoro's interest in dance and movement was always reflected in the space and movement of her artwork. Castoro incorporated her ideas into her paintings, drawings, and sculptures. Some of her art was performance centered; actions, images, and movements in a studio or on the street. Much of the art was based on her interest in political activities. Castoro did not associate herself with feminist movements because she thought they were too restrictive and created a type of segregation. She married fellow artist Carl Andre, the marriage lasting seven years. During this time, their studio was the center for other minimalist artists. Her early paintings were made with sophisticated colors. She turned to monochromatic images based on her feelings about the Vietnam War. In the 1970s, she also experimented with sculptures and their relationships in installations.

The 1960s was a period of political unrest, and Castoro experimented with structural compositions based on organic shapes and surrealistic suggestions. Castoro said, "I want to carve space. I am carving space."[7] Her minimalistic compositions allowed her to repeat a specific image in multiple iterations. Castoro used irregular geometric shapes for the basic concept and subtly repeated the idea. Land of Lads (8.4.13) was an installation representing her work with freestanding elements presenting an architectural look and resembling a crowd of people standing along the building. The large, individual sculptures reflected against the white background of the wall. The sculptures were made with epoxy and painted with dark colors. The vertical and horizontal lines are based on geometric forms only in organic shapes. The sculptural elements also were reminiscent of Castoro's interest in the movements of a dance. "Castoro developed her language between minimal art and conceptual art. She combined painting, performance, stage design, and sculpture and described herself as 'painter/sculptor.'"[8]

"Rosemarie Castoro. Enfocar a l'infinit" is the first major institutional retrospective of Castoro's work and focuses on 1964-1979. Castoro (1939-2015) will carry out his sixth career in the State Units at a time when minimalism and conceptualism are part of the New York forefront. The exhibition shows his work in detail for the first time and fills in the diversity of an artistic practice that includes abstract painting, conceptual art, performative actions in the street and in the studio, poetry, mail art, sculpture, installation lacions i land art.

Charlotte Posenenske

Charlotte Posenenske (1930-1985), a renowned artist, was born in Germany in 1930 and faced numerous challenges throughout her life. Her father was of Jewish descent, which made him a target of persecution during World War II. Sadly, her father's death when she was only nine years old forced her into hiding. Despite these challenges, she did not let her circumstances define her future. After the war, she pursued her passion for art and enrolled in a German institute, where she honed her skills in set and costume design for the theater. Posenenske's early artistic career was characterized by her interest in Abstract Expressionism, evident in her paintings. However, she would later shift her focus to minimalist sculptures, where she experimented with various materials. She finally settled on sheet metal structures she created by folding and spraying them with a single color. This unique approach became her signature style and was well-received by art enthusiasts and critics alike.

She liked to create a series for an idea using multiple images. She opposed the social structure in art and focused on interesting the public in the changeable nature of her sculptures. Posenenske retired from the art world in 1968 and became a sociologist specializing in industrial relations. Posenenske developed various Vierkantrohre Serie sculptures (Square Tube Series) (8.4.14, 8.4.15). The steel tubes resemble heating and air conditioning or ventilation shafts. Each sculpture in the series was arranged in different configurations. Some of the sculptures in the series were made from corrugated cardboard, shaped the same way as the steel tubes. Posenenske even allowed those displaying her work to organize the parts however they wanted; she did not prescribe any unique look. Posenenske was not interested in the traditional art market and sold her work only for the cost of the materials. Overall, Charlotte Posenenske's journey is a testament to her resilience and passion for art. Despite facing numerous challenges, she remained committed to her craft, and her innovative approach to sculpture has left an indelible mark on the art world.

The objects are intended to have the objective character of industrial products. They are not intended to represent anything other than what they are.* Charlotte Posenenske (1930 - 1985) was born in 1930 in Wiesbaden, Germany. Between 1951 and 1952, she studied at the Stuttgart Academy of Art under the famous painter Willi Baumeister. In 1959 she started her career as a freelance artist, lasting until 1968.

Jo Baer

Jo Baer (1929-) was from Seattle, Washington. Her mother supported women's rights and was a model for Baer. As a child, Baer attended Cornish College of the Arts to study art; however, she moved to the University of Washington for biology. At school, she met and married, the marriage lasting only a few years, and in 1950, Baer went to Israel to learn about the new state. After World War II, Israel established a place for displaced Jews to find a home. They developed the concept of the kibbutz, a place for small groups to live and work together according to defined social constructs. Baer returned to New York City and completed her master's degree in psychology. She had two more marriages during the next ten years, a son, and a long-term relationship with another artist. Baer continued to work on her art, rejecting Abstract Expressionism and developing her hard-edge painting style. She became part of the Minimalist community, showing with other similar artists and establishing herself as an avant-garde artist.

By 1962, Baer had developed her minimalistic style of painting. Her work was based on different-sized squares and rectangles based on hard edges. In her early series, Korean (8.4.16), she based the painting on a completely white background. The thick, dense white paint was set in the middle of narrow strips of blue and black. The banding colors gave the paintings an optical illusion, almost shimmering or moving. Baer did not consider the dark outside bands as a border or the large white-painted section as a center. She wanted the colors to push on each other. In many of her paintings, Baer added two colors for borders against a solid center of color to produce the same idea of movement. Baer wrote about her work and stated she wanted to make "poetic objects that would be discrete yet coherent, legible yet dense, subtle yet clear."[9] Later Baer left New York and moved to Europe, changing her painting style and no longer wanted to be known as an abstract artist.

On the occasion of the artist's two concurrent exhibitions at our New York gallery, Jo Baer discusses the works on view, which range from 1960 to the present and reflect the artist’s departure from Minimalism towards a new, image-based aesthetic in her practice.

Nasreen Mohamedi

Nasreen Mohamedi (1937-1990) was born in Karachi, India, now part of Pakistan. Her father was a wealthy businessman, and the family was considered part of a privileged family. Mohamedi studied art in London and Paris before she returned to India and joined the Bhulabhai Desai Institute for the Arts. By 1972, she was a successful artist and taught art at Maharaja Sayajirao University until her death. Mohamidi traveled to different parts of the world and was influenced by Zen concepts, the forms of Islamic architecture, and nature's environments. She was also exposed to many Western art movements; however, her work was mainly based on Buddhist ideals, and her work was based on the concepts of the use of positive and negative spaces. Patterns and intersecting lines are seen in much of Mohamedi's art. She created abstract art based on non-Western ideals. Her work was not well-known outside of India during her lifetime. Today, Mohamedi is considered one of India's most important modern artists. She expanded the descriptions of international modernism.

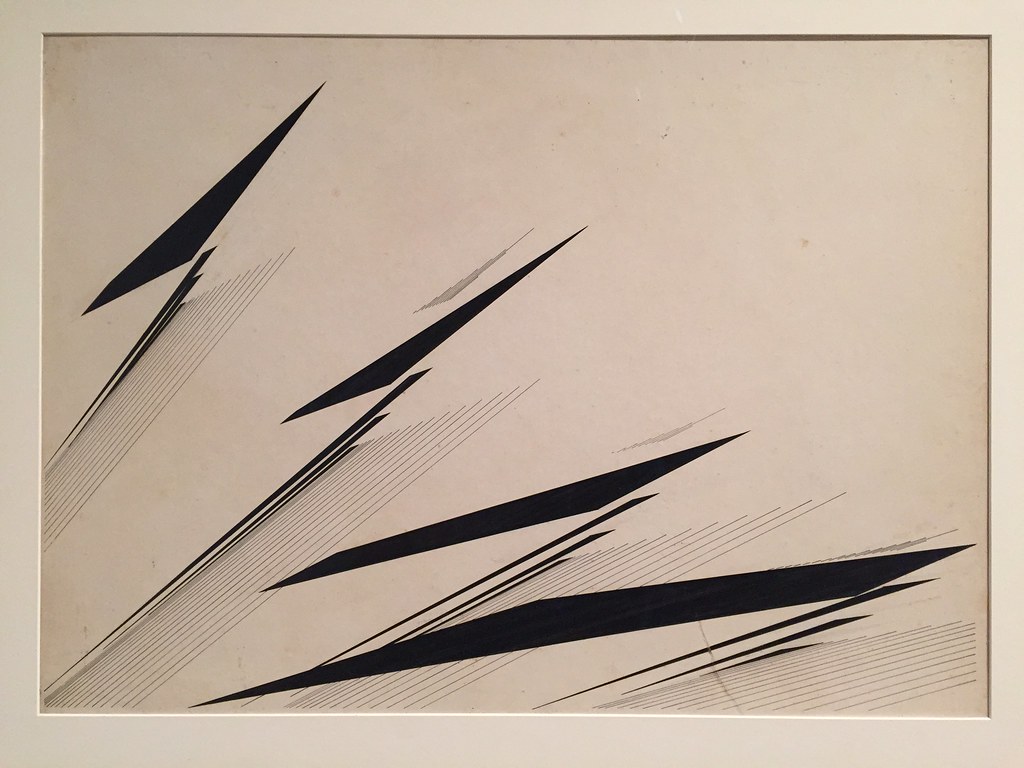

Mohamedi's artistic preference was to use a pencil and paper for drawing her lines. Her style was minimalistic, characterized by organic shapes with hard-edged lines. She masterfully employed primary forms to create intricate images while retaining a simplistic look. Discipline of Line I (8.4.17) is a set of straight lines, each supporting the others. Some lines are thin and delicate, while others are deep and dark, with hard edges forcing the viewer to move from space to space. Each section moves from the more prominent dark figure to narrower yet smaller dark lines, finally supported by the fine lines. The New York Times wrote, "Her fine-drawn linear planes floating in space or shattering into cascades, feel both timeless and futuristic, calligraphic and architectural."[10]

We present a video from Nasreen Mohamedi’s extraordinary exhibition at KNMA in 2013's archive from the museum. In the history of Indian Modernism, Nasreen Mohamedi is a distinct figure. This retrospective exhibition draws connections between Nasreen’s works from the early 1960s to the 80s, highlighting her singular vision that runs through her early paintings, collages, photographs, diaries, and drawings.

Beverly Pepper

Beverly Pepper (1922-2020) was born in Brooklyn, New York. Her parents were Jewish immigrants escaping the violence and persecution in Europe. Pepper described her mother and grandmother as strong women who instilled in her the idea she could do whatever she wanted and was not limited by the concepts of being a feminine woman who married and had children. Eventually, Pepper did marry twice and had two children.

Pepper studied art and industrial design at the Pratt Institute. At first, Pepper worked for an ad agency before developing her sculpting style. After World War II, she went to Europe to study in Paris. Pepper started making sculptures with wood and metal. The traditional carving path was a male domain forcing her to become more creative with the materials. At the time, sculpting with metal was considered an art medium needing muscle, sweat, and a masculine art style. In the 1960s, Pepper started to use a torch on stainless steel and established a methodology she continued to follow. Although it was unusual for a woman to sculpt in metal, it was even more novel to fabricate the works herself. As one of the few women, she put on her helmet and used her torch to unleash the showers of sparks from the metal. Pepper said, "I never thought of myself as a 'female sculptor.' Perhaps because I'm not in the art scene, I don't know I'm not supposed to be doing this!"[11]

Pepper's minimalistic steel sculptures are based on geometric shapes. She frequently used Cor-Ten steel, one of the first sculptors, to incorporate the material, which developed a natural patina resembling rust. Her stainless-steel sculptures are shapes formed into box-like images. She paints the inner planes of the surfaces with one bright color. The polished surfaces reflect the light, and the sculpture resembles the landscape. Alpha (8.4.18) is made from steel and painted orange, usually found in a construction zone. The four triangles are layered to portray pairs, a simple concept creating a complex image. The interleaved, prominent tent-like forms are formed with sharp angles. Perre's Ventaglio III (8.4.19) is an example of Pepper's application of stainless steel. She used the shiny, mirrored look of the steel and painted to create an interplay between the steel, the color, the shapes, and the reflective landscape. Pepper believed the interactions created previously unseen observed images. The light in this sculpture creates multiple planes as the enamel paint stops the light and produces another contrast.

[1] Retrieved from https://magazine.artland.com/minimalism/

[2] Retrieved from https://www.artic.edu/artworks/89403/untitled-12

[3] Retrieved from https://whitney.org/collection/works/5551

[4] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_lear...teen-iii-1968/

[5] Retrieved from https://whitney.org/audio-guides/51?...&page=1&stop=1

[6] Retrieved from https://editions.lib.umn.edu/panorama/article/in-the-tower/ (30 October 2020)

[7] Retrieved from https://www.rosemariecastoro.net/

[8] Retrieved from https://www.rosemariecastoro.net/event/zeichensprache/

[9] Retrieved from https://www.jobaer.net/biography

[10] Retrieved from https://www.talwargallery.com/exhibi...#tab:slideshow

[11] Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/05/o...pper-dead.html