8.2: Pop Art (1950s-1960s)

- Page ID

- 209565

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

The Pop Art movement emerged in the 1950s in England and the United States, breaking away from traditional art concepts by incorporating ordinary objects such as comic books and advertising used in mass culture. Following a period of experimentation and increased consumerism after the war, artists were inspired by the world around them to create art based on prevalent culture. Unlike the Abstract Expressionists, the turbulent political climate and growing consumerism influenced artists to focus on bright primary colors and use printing and painting techniques that reflected realism. Pop Art artists linked their work to mass media such as film, television, cartoons, and everyday mass-produced images, resulting in a style that blurred the lines between high-class art and low-class culture. By focusing on recognizable and mundane images, Pop Art became one of the most recognized movements, as the artists sought to connect art with the media world surrounding ordinary people and develop art as a commodity.

A group of UK-based artists delved into the world of movies, comics, technology, and advertising, using materials from the mass-produced world to create collages. They sought to connect with the mass media of advertising, television, and film that surrounded them, despite being aware of other artistic movements and styles. The challenge of blending different methods and mass-produced materials led them to produce art with new meanings. However, female Pop artists faced significant hurdles in being accepted by the art community. Pop art perpetuated sexual and stereotypical roles for women, leading to a widespread impact on how women were viewed. Male artists often depicted women in sexualized ways and reinforced traditional gender roles. In contrast, female Pop artists had to explore new directions in the Pop art style, using materials and views that supported women's movements and liberation.

Artists in this section:

- Pauline Boty (1938-1966)

- Evelyne Axell (1935-1972)

- Corita Kent (1918-1986)

- Marta Minujín (1943-)

- Marisol Escobar (1930-2016)

- Idelle Weber (1932-2020)

- Kiki Kogelnik (1935-1997)

Popular, witty, sexy, glamorous – pop art exploded onto the cultural scene in the early 1960s. A new generation of artists rebelled against ‘high art’ to embrace the world of advertising, television, film stars, pop music, and consumerism. Pop art shocked many but inspired even more.

Pauline Boty

Pauline Boty (1938–1966), the only girl in a family of boys, was born in England in 1938. Her father was an exceptionally strict man who believed women had a specific place in the world. Despite her father's disapproval, Boty received a scholarship to attend Wimbledon School of Art, where she focused on stained glass. However, she was discouraged from pursuing painting as few women were accepted into the school of painting. Nevertheless, Boty continued to paint and make collages independently and met other young artists starting as Pop artists. In 1961, she exhibited twenty collages for the first Pop Art show. While Boty was encouraged to work as an actress, she aspired to be an artist. Notwithstanding her beauty, the press did not view her as an artist but as a glamorous actress. Boty has since become one of the early feminist artists who used her body in her art to develop her distinct style of collages with photo-realistic painting. She aimed to celebrate the sexuality of a woman from a female perspective rather than the usual male context of feminity. Scene magazine, in 1962, wrote, "Actresses often have tiny brains. Painters often have large beards. Imagine a brainy actress who is a painter and a blonde, and you have Pauline Boty."[1]

Boty also incorporated the events of the period folding the Vietnam War, distorted masculinity, and civil rights abuses into her images. Boty was considered the first female British Pop Art artist. She was considered intelligent, attractive, and energetic. In 1963, she married after a short romance. Unfortunately 1965, Boty was diagnosed with cancer when she was only twenty-seven. She was pregnant, and during a checkup, the cancer was discovered. The only way to receive treatment for the tumor was an abortion, and she opted to have the baby, rejecting the treatment. Boty died five months after her daughter was born. After her death, Boty's artwork was collected and put in a barn for almost thirty years and only rediscovered in the 1990s. Although she did not live long enough to create a large set of paintings, today, her work is one of the best examples of Pop Art.

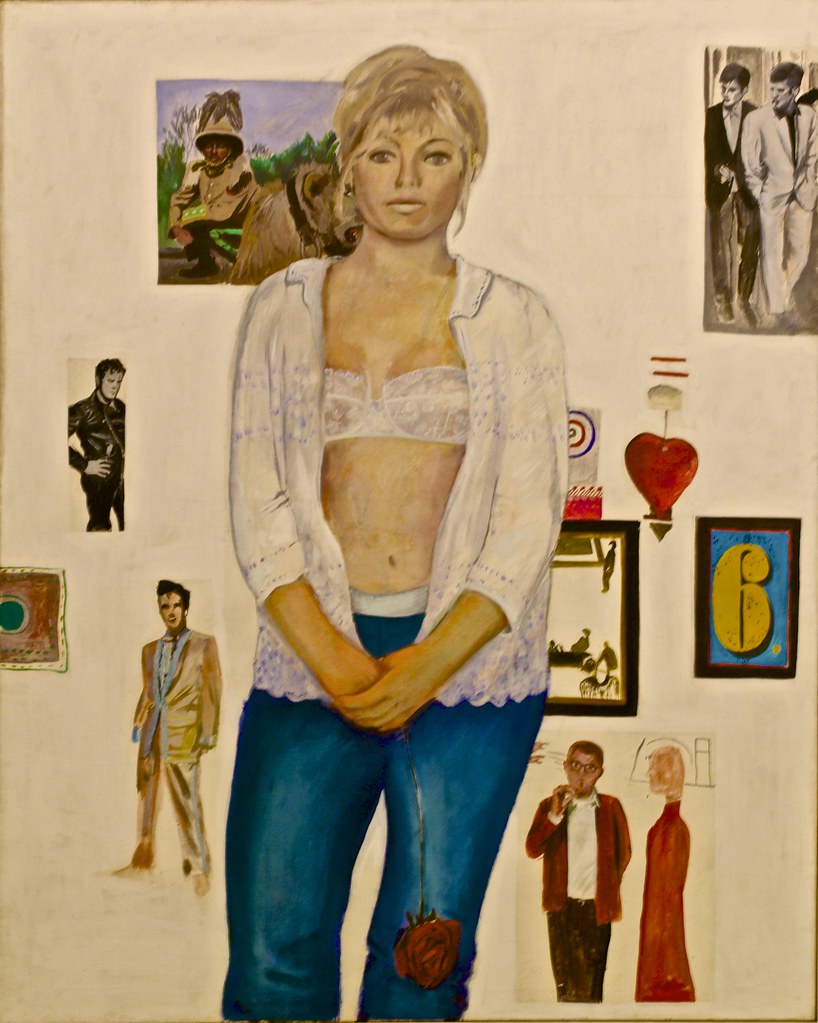

The artwork "Colour Her Gone" (8.2.1) features a beautiful blend of swirling colors in shades of gray, red, pink, and green. A rose pattern runs down the center of the image, giving it a wallpaper-like appearance. The focal point of the painting is a relaxed portrayal of Marilyn Monroe wearing a simple blue top. What makes this painting unique is that most male painters would depict Monroe in a sexualized manner. However, the artist, Doty, captured a moment when Monroe was simply happy and casual, depicting her as herself instead of a sex symbol. Doty embraced female form and sexuality through her female ideals, often painting women against bright, colorful backgrounds and incorporating flowers. One of Doty's early roommates, Celia Birtwell, was a textile designer who frequently posed for David Hockney, who painted multiple images of her. In "Celia Birtwell and Some of Her Heroes" (8.2.2), Doty painted her roommate surrounded by some of her favorite male idols, including Elvis Presley and David Hockney. The painting also features accent points of red, including a heart and a red rose. Birtwell is centered in the middle of the canvas, exuding an air of sexuality with her casually dressed open shirt.

Evelyne Axell

Evelyne Axell (1935-1972) was born in Belgium; her father was a silversmith and jeweler. Even as a small child, Axell was defined as the local province's most beautiful baby. During World War II, her home was destroyed by bombs. However, she finished high school and studied pottery at a local art school before switching to drama school and becoming an actress. She married a film director, had a son, and worked as a television announcer. In 1964, she grew tired of acting and worked with René Magritte, learning to enhance her abilities in painting. As she was honing her skills, her husband filmed documentaries about Pop Art, an inspiration to Axell, who developed her pop style. She became one of Belgium's first pop artists, although still not accepted by galleries, and Axell began to use only her last name to overcome the perceptions of sexual discrimination. Her work was influenced by the political events of the 1960s, particularly women's liberation. Axell became known for her erotic works of nude females and multiple self-portraits.

In the masterpiece"Portrait Fragment" (8.2.3), the artist deliberately highlighted distinctive parts of her physical form, a recurring theme in her artistic works. This particular piece showcases her face, which is portrayed in a slightly fragmented manner with linear waves. The striking contrast created by the bright red circle surrounding her face and her vivid red lips against the blue-green background amplifies the visual impact of the artwork. The artist's meticulous attention to detail is evident in how she has emphasized her blue eyes by surrounding them with white and black, thus drawing the viewer's attention toward them. Notably, the artist has employed traditional oil paint in this painting, providing a touch of classical elegance to the overall composition.

Interview with curators Jessica Morgan and Flavia Frigeri about women in Pop Art and Evelyne Axell.

Corita Kent

Corita Kent (1918-1986) was born in Iowa as Frances Elizabeth Kent. In 1936, be became a nun in the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary and changed her name to Sister Mary Corita. She completed her degree in art, a bachelor's degree from Immaculate Heart College, and a master's at the University of Southern California in 1951. She lived and worked as a num for thirty years, teaching art at Immaculate Heart College and known for her avant-garde teaching methods, attracting many prominent artists to her classes. During the 1960s, her work became more secular, supporting humanitarian problems and protesting the Vietnam War. Her work was considered blasphemous by the Catholic church leaders, and she left her life as a nun to continue working for women's and civil rights and anti-war protests. She used silkscreen as her medium; her work was not respected or treated as serious art at the time. During the 1950s, most religious arts demonstrated piety with white or blue flowing robes based on a pastel palette. Kent's art was primitive and abstracted, although dark at first. By the late 1950s, she began to illustrate text from popular writings. In the 1960s, she was widely exhibited, and her art was included in multiple magazines and newspapers; however, she still was not included in art history textbooks.

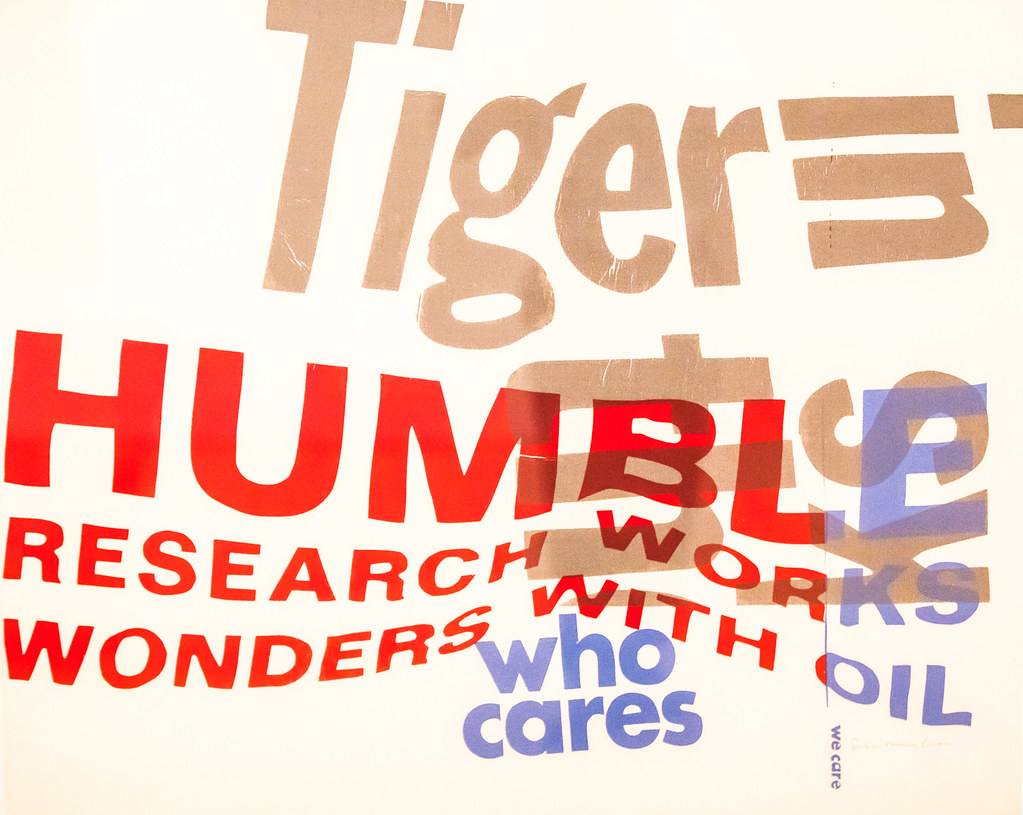

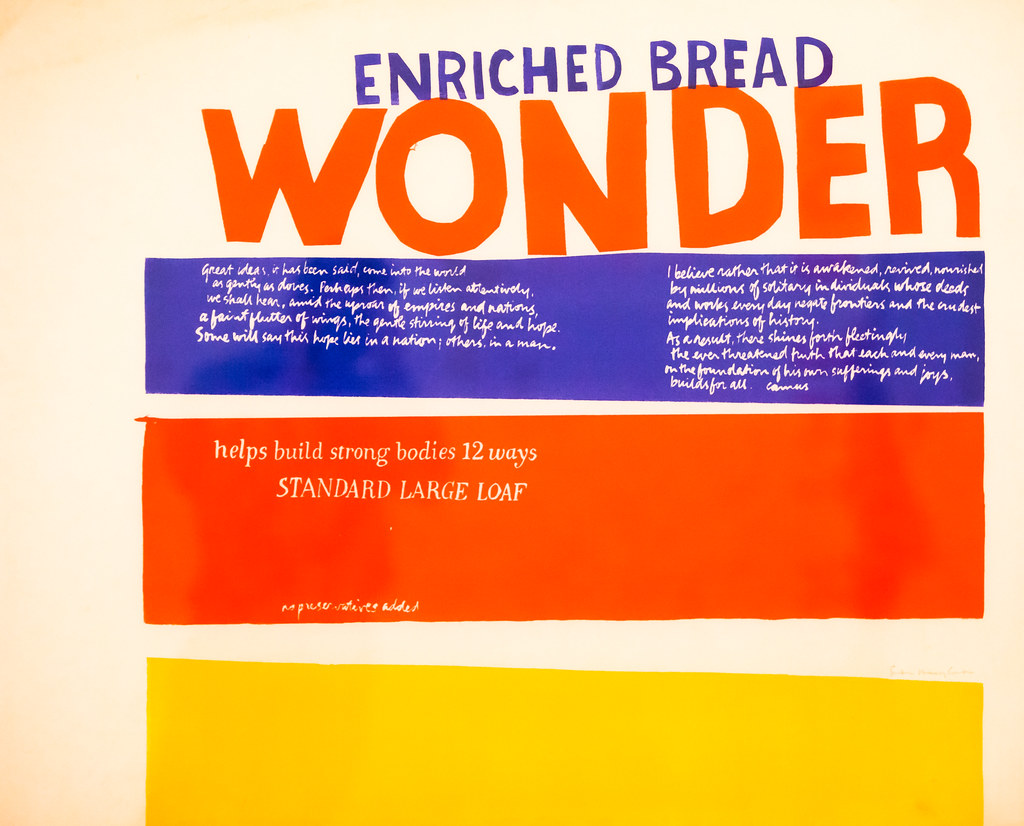

In the late 1960s, some of her work became more political and social, similar to Warhol. Kent inspired themes from pop culture, a mix of spiritual themes, and American consumerism. She was a social activist and worked with current issues of poverty or racism, and war. Kent took any signs, tore out pieces, crumpled images, and photographed them to use as the basis for her silkscreens, all depicted by bold graphics and emotional texts. To construct the layouts for the printmaker, she layered the pieces of lettering or image using multiple sheets of paper. Based on the rise of commercial consumerism, "…she used words like 'tomato,' 'burger,' and 'goodness' and made them into messages about how we live, and about humanitarianism and how we care for others."[2] The colorful words on her silkscreens appeared simple while carrying a complex social meaning. We Care (8.2.4), and Enriched Bread (8.2.5) were made from assembled terms printed on nonwoven synthetic fabric. Kent frequently used a specific word highlighted in red to convey part of the message, HUMBLE in the first image and WONDER in the other image, layering different messages to support her pursuit of social justice.

Kent also used words by different prominent authors and civil rights leaders. Enriched Bread contained the words of the French philosopher Albert Camus in his Flutter of Wings-Hope. Kent applied the words in script format with white on a highly contrasting royal blue:

Great ideas, it has been said, come into the world

as gently as doves. Perhaps then, is we listen attentively,

we shall hear, amid the uproar of empires and nations,

a faint flutter of wings, the gentle stirring of life and hope.

Some will say this hope lies in a nation; others, in a man.

I believe rather that it is awakened, revived, nourished

by millions of solitary individuals whose deeds

and works every day negate frontiers and the crudest

implications of history.

As a result, there shines forth fleetingly

the ever-threatened truth that each and every man,

on the foundation of his own sufferings and joys,

builds for all.

Marta Minujín

Marta Minujín (1943-) attended the National University Art Institute in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where she was born. She was part of a student exhibition in 1959. Minujín secretly married when she was sixteen by lying with false records documenting she was eighteen later. Because Minujín was legally married, she could travel internationally by herself and was fortunate to receive a scholarship for further study in Paris. While Minujín was in Paris, she created "livable sculptures"and1962, exhibited them with other artists considered avant-garde at the time. Part of the exhibit was to burn her other paintings. Minujín went to New York City and spent time with other early Pop artists, including Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. When she was asked what it was like to be an Argentinian artist who worked internationally, she responded, "When I met people, I was asked, 'Are there artists in Argentina?'"[3] After returning to Buenos Aires, Minujín created several displays, some interactive. She became known for her Pop Art and avant-garde constructions based on the criticism of Latin American political issues.

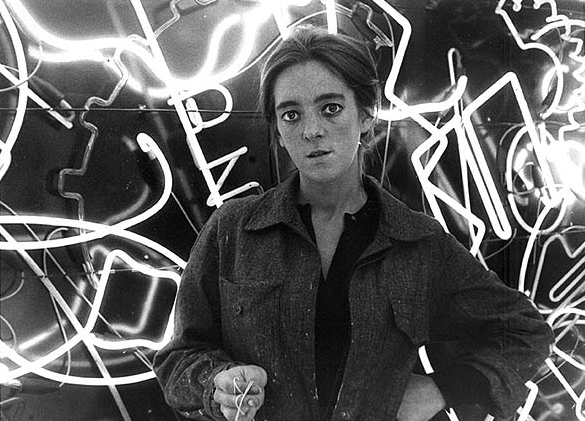

In 1965, Minujín created the spaces she called La Menesunda (Mayhem) (8.2.6) based on eleven rooms. Each room had an entrance with neon lights. A group of viewers walked through the rooms, each filled with a different theme; a freezer with fabric meat hanging out, a dentist's office, or a cosmetic counter complete with the person ready to apply makeup. One of the rooms had a couple in bed talking, a risqué scene at the time in Catholic Argentina. In each room, she hung advertising, how advertising influences the marketplace, and the themes of Pop Art. Each room had colors and smells, forcing the viewer into different situations. The cosmetic counter was painted in bright bubblegum pink, while the refrigerator room was stark white like the insides of a refrigerator.

Minujín created a series of images for a happening called Leyendo Las Noticias (8.2.7). At the time, Argentina was ruled by different military dictatorships or failing governments. Minujín was concerned about the plight of women in this period and the government's manipulation of mass media. In the exhibit, she wanted to create a dialogue about feminism and how women's lives are unstable and repressed. She used the newspaper because the mass media brought people information about their world. However, the information and words in the newspaper can be restrictive.

Minujín posed in different positions and covered her body with newspapers and photos of each pose. Then she walked into the river until the newspaper slowly dissolved and disintegrated, moved by the current. Minujín was wrapped in the news of Argentina's political turmoil, liberated when the paper washed away. Also, the subsequent military coup emerged in Argentina with additional restrictions.

Although Minujín created the Torre de Babel (8.2.8, 8.2.9) in 2011, she incorporated her past art concepts of Pop Art into the twenty-five-meter tower. Using the perceptions of the impact of advertising, the written word, books, comics, and other elements, Minujín created the tower based on the idea of babbling, the confusing noise heard when multiple people speak simultaneously or when they are talking in different languages. She stacked and packed different types of books into the frame. Visitors could walk up the tower as music played, and the word "book" was repeated in multiple languages. Minujín collected over 80,000 books from embassies around the world representing forty languages.[4] The concept for this installation was based on a reproduction of the Parthenon she created in 1983 using over 100,000 banned books.

Conceptual and performance artist Marta Minujín was born in Buenos Aires in 1943 and continues to work there today. From the mid-1960s, Minujín became one of the most energetic contributors to the pop art scene in Buenos Aires.

Marisol Escobar

Marisol Escobar (1930-2016) was simply called Marisol. Her parents were from Venezuela and lived in Paris when Marisol was born. The family was wealthy and traveled extensively between Venezuela, Europe, and the United States. Her mother committed suicide when Marisol was only eleven leaving Marisol traumatized and not speaking until her late twenties. Her father sent her to New York for boarding school before the family finally settled in Los Angeles. After high school, Marisol trained in the arts at schools in Los Angeles, Paris, and New York. She became part of the New York City Pop Art culture, befriending Andy Warhol and starring in two of his movies. Instead of painting, Marisol decided to sculpt. Initially, she made small figures of clay or carved wood. She was influenced by comics and children's books, making images not acceptable to other artists.1958 Marisol developed a new style for her exhibition and combined different media to create large constructions. It was difficult for young female artists to be accepted, so Marisol chose subjects relatable to the female experience. Her early shows were successful; however, she remained elusive. In 1965, a magazine reporter said, "her chic, bones-and-hollows face (elegantly Spanish with a dash of Gypsy) framed by glossy black hair; her mysterious reserve and faraway, whispery voice, toneless as a sleepwalker's, but appealingly paced by a rich Spanish accent."[5] Marisol frequently left town and traveled to other parts of the world, leaving her artwork and dealers. In the 1960s, she was well-received by the press and considered a significant sculptor, with large crowds attending her shows. Marisol had a large body of work, and after her 1968 exhibition in Venice, she started to travel for five years and never again created much work or exhibited in galleries. She was later left out of the history books.

Marisol was a talented sculptor who used unusual wood, fabric, mirrors, and other paraphernalia materials to create her work. The Party (8.2.10) contains fifteen figures and three wooden panels arranged as a satire of New York society's exclusive and frequent party scene. The figures are all assembled to stand on their own without interaction between the different participants. The life-sized female images appear submissive, the proper form for women then. They all appear uncomfortable with attending the party, perhaps reflecting Marisol's aversion to staying in large groups. Each of the figures has the face of Marisol in different media. They are all dressed in clothing demonstrating wealth. Marisol used a variety of media for the images and their adornment.

Marisol Escobar, The Party, 1965-66, fifteen freestanding, life-size figures and three wall panels, with painted and carved wood, mirrors, plastic, television set, clothes, shoes, glasses, and other accessories, variable dimension.

When Marisol constructed LBJ (8.2.11), Lyndon B. Johnson was president of the United States. He appears holding his wife and daughters in his hand, their faces smiling. He is holding the figures right below his heart, demonstrating his protection of them or perhaps controlling them. The face of Johnson is in opposition to the females in his hand; the face is blocky and grimacing, his excessive nose jutting out of his face. The head was made from glued and laminated wood, and the ears, nose, and chin were attached. The figure is shaped like a coffin, reminding viewers of how Johnson came to office after the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Johnson was very unpopular at the time Marisol made the sculptor. Johnson said, "I am a dominating personality, and when I get things done, I don't always please all the people."[6] Marisol was working on a series of British portraits. When they wanted her to include prime minister Harold Wilson, she agreed that if she could add sculptures of Charles de Gaulle, Francisco Franco, and Lyndon Baines Johnson, she would accept the commission. The four formed an exhibition called Figures of State.[7]

Idelle Weber

Idelle Weber (1932-2020) was initially born as Tessie Pasternack in Illinois and adopted as an infant. As a child, she was always interested in art and went to museums in Chicago weekly. Weber continued visiting galleries and museums after the family moved to Southern California. After high school, she studied art at Scripps College and UCLA, receiving bachelor's and Master's degrees in art. In 1956, Weber moved to New York. Her first encounters were with galleries that did not take female artists. Weber took additional design classes. Robert Motherwell was teaching at Hunter College, and when Weber asked him if she could audit his class, Motherwell responded that married women who had children were not allowed because they do not continue painting after class. Weber was married and had two children, and continued to paint. She could finally show her work at a gallery, becoming acquainted with other Pop artists in New York. In the 1960s, Weber created Pop art before moving to more Photorealist methods in the 1970s. She also started teaching at New York University and then Harvard University.

Weber's trademark was creating black silhouettes with bright backgrounds, either colored or patterned, using multiple types of media. Munchkins I, II, & III (8.2.12) was made as an oversized silhouette of men riding escalators at the newly constructed Pan Am building. Using hard-edge techniques, each man is visible in detail, from holding cigars to protruding stomachs. The yellow and black checked background and slanted escalator used geometric shapes to provide a perfect background for the figures. Weber carefully outlined each character to create their silhouette and details. The flatness in the painting reflects the lack of perspective in commercial advertising. She leaves a lot of space on the checkered background and the stark black of the escalator, bringing drama and emotion to the painting. Without interaction, the silhouetted men move through the daily 'rat race' up and down the escalators of any standard office.

Jump Rope Lady (8.2.13) continues Weber's use of black silhouettes to provide deep contrast to the figures she used. The woman is flat, dark, and anonymous in society while continually jumping. Usually, jumping rope is a joyous experience; however, it is unknown if the woman is happily jumping rope or if the rope represents the daily, continuous grind people experience. Weber's silhouettes present an ambiguous image following the standardization and commercialization of advertising and the basis for Pop culture.

Kiki Kogelnik

Kiki Kogelnik (1935-1997) began her career in Vienna, near where she was born in Austria. Initially, Kogelnik was engaged to an Abstract Expressionist artist, and then she moved to New York in 1962 and became part of the Pop artists working in New York. Kogelnik wore ornamental, extravagant clothing and hats and became a sensational person herself. Her colorful clothing was reflected in her art, and she used intense pop art colors and materials. Kogelnik used her friends to make life-sized cutouts as part of her work. Her studio was in the garment district, and Kogelnik saw the thousands of different iterations of clothing styles and materials, ideas she used in her work. In the late 1960s, Kogelnik went to London, married, and had a son before returning to New York City at the end of 1969. At that time, Kogelnik started focusing on female issues, especially how women were portrayed in advertising. The Space Race and new technologies influenced how she developed representations of her female figures. Many of her figures are techno-robotic images seeming to float in their environment. Kogelnik used vibrant colors and bold shapes following the concepts of modern advertising. She even created a series named "Women's Lib."

Kogelnik's images were based on how women may be empowered and still have assigned roles. The women's faces are almost robotic, with little emotion. Their bodies had no context reflective of their portrayal in fashion magazines. Female Robots (8.2.14) display a woman with multiple types of parts, each suited for the diversity of a woman's life. Some parts are disconnected and floating, all appearing emotionless. The silhouetted body parts are painted with contrasting, bright colors appearing to float through the painting. Kogelnik used her trademark metallic and colored circles throughout the work. Kogelnik thought the work based on her previous interest in robotics was "beautiful, rich, worldly, superficial, bored, neither happy nor unhappy, no deep thoughts, no sentiment, no feelings."[8] Superwoman (8.2.15) reflected Kogelnik's portrayal of women in fashion magazines and advertising. The figure is larger-than-life scale. Oversized glasses cover her eyes and much of her face, hiding any emotion. Her body is stiffly posed in an unnatural stance, the oversized scissors mimicking the pose. The figure has a hard-edge outline, and the background is monochrome, unlike most of Kogelnik's work. The image is similar to a cartoon or comic book.

[1] Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/books/20...f-pauline-boty

[2] Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/apr/22/corita-kent-the-pop-art-nun

[3] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/650

[4] Retrieved from https://www.instituteforpublicart.or...orre-de-babel/

[5] Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/03/a...ies-at-85.html

[6] Retrieved from https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81851

[7] Retrieved from Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, https://assets.speakcdn.com/assets/2...isol-ebook.pdf

[8] Retrieved from http://www.kikikogelnikfoundation.site/Kiki-Kogelnik/