7.2: Fauvism (1905-1910)

- Page ID

- 217504

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

During the early twentieth century in France, a groundbreaking art movement known as Fauvism emerged. This revolutionary movement dared to challenge the traditional techniques used by Impressionists and instead, boldly emphasized the use of vibrant, intense colors straight from the tube. The visionaries behind this movement, including Henri Matisse and Andre Derain, brilliantly experimented with color to create a dynamic sense of movement and liveliness in their artwork. It's crucial to note that although Fauvism and Expressionism may appear to be similar at first glance, they differ in their primary focus. While Fauvists placed great importance on the organization of the image, Expressionists were primarily concerned with the communication of emotions through their art. At their first exhibit at the Salon d'Automne in 1905, one critic declared, "A pot of paint has been flung in the face of the public."[1] The artists' intense colors to portray emotions and aggressive brushstrokes with enthusiastic loose globs of paint added a decorative effect to their work. They were interested in complementary colors and how they appeared side by side. They had little else in common except color, each painting a different subject matter. Most of them moved on to other styles later in their life. Although it only spanned a decade and included three exhibitions, Fauvism left a lasting impression on the works of the participating artists. Even beyond those specific exhibitions, the style remained evident in their subsequent creations. Arts in this section include:

- Émilie Charmy (1878-1974)

- Nadežda Petrovic (1873-1915

- Alice Bailly (1872-1938)

- Maria Magdalena Laubser (1886-1973)

A concise overview of the Fauve style and why it is so colorful, focusing on the artists Henri Matisse and Andre Derain.

Émilie Charmy

Émilie Charmy (1878-1974) was a French artist whose life was marked by tragedy. After losing her parents in her teenage years, Émilie was taken in by relatives in Lyon. Despite societal norms dictating that women should become teachers, Émilie was determined to pursue her passion for art. She continued to study and practice, eventually becoming a successful painter. Her early works mainly consisted of paintings of women in domestic settings or still-life, which sold well. However, Émilie longed to create art that fulfilled her artistic aspirations and expressed her innermost self. Despite her challenges, Émilie continued to paint and grow as an artist, leaving behind a legacy of beautiful and meaningful works.

In 1903, she moved to Paris, where she became part of the Fauve artists headed by Matisse. Like the others, she experimented with new methods of applying thick paint with crude, heavy brushstrokes. Although she was associated with the artists in exhibitions, her work was hung separately, receiving little attention as a female painter. Because of her bold use of color, one of the French novelists stated, "Émilie Charmy, it would appear, sees like a woman and paints like a man; from the one she takes grace and from the other strength, and this is what makes her such a strange and powerful painter who holds our attention." [2]

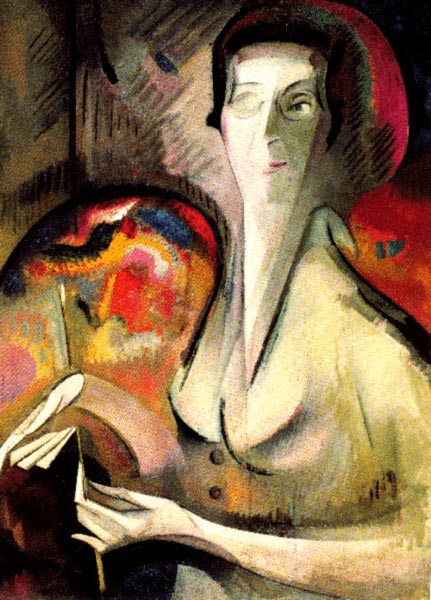

During this time, gender roles were well defined, and women did not paint from nude models, only encouraged to paint the traditional roles of women and children. However, Charmy did not follow the trend. Instead, she used female models she posed in austere settings, applying her unique brushwork and color and sparking much controversy in her early shows. When she could not find a suitable model, she used it herself. Self-Portrait in an Open Dressing Gown (7.2.1) shows her sitting casually against the dark background. Her robe and skin are painted with muted colors applied with broad brushstrokes of thick paint. Self-Portrait with an Album (7.2.2) is painted with a small palette of colors; however, the dark colors are contrasted, black against red, with the bright, pale skin color. She presents two different looks in the paintings; one has a reticent look on her face, while the other displays more confidence. Charmy's thick, fast brushstrokes sometimes appear crude; however, her brushwork brings a unique visceral quality to her paintings.

Nadežda Petrovic

Nadežda Petrovic (1873-1915) was born in Serbia and graduated from the Women's School of Education. She taught art at the university in Belgrade before going to Germany for further study. Petrovic was successful and exhibited her work in multiple European shows. In addition to her work as an art teacher and artist, Petrovic was also deeply committed to various human rights organizations. During the Balkan Wars in 1912, she worked as a nurse, tending to the wounded and providing much-needed support to those in need. The Serbian government recognized her bravery and dedication to the cause and commended her for her service. Despite the dangers she faced while working in the field, Petrovic remained committed to her work. After the Balkan Wars, Petrovic resumed her painting, creating some of her most stunning works during this time. However, her life was cut short by the Austria-Hungary War in 1914, when she once again volunteered as a nurse. Tragically, she contracted typhoid fever while caring for wounded soldiers in a Serbian hospital and passed away soon after. Petrovic's legacy as a talented artist and devoted humanitarian lives on to this day.

Petrovic painted portraits; however, her primary focus was landscaping, particularly those representing the history and views of Serbia. She used solid and bold brushstrokes in thick layers of paint on the canvas creating vortexes of color. Red was generally the focal color with purple and black shadows. Resnick (7.2.3) was a local village she portrayed through its winding road starting at the edge of the painting, trees, and wooden fences adjoining the road. Some of the paint was applied with thick, pasty strokes, and others with colors of thin glazes. Petrovic used a varied palette to express the character and feeling of her village and the rhythm of the road. Ksenija Atanasijevic (7.2.4) was one of the first females to become a professor at Belgrade University and the first to receive a Ph.D. in Philosophy. She became a noted Serbian philosopher and a friend of Petrovic, who painted her portrait. Petrovic used her unique brushstrokes, vertical gray in the background, diagonal lines in the sky, and foreground snow. Atanasijevic, who was sixteen, is wearing an oversized black hat she recently purchased in Paris. Her black clothing and determined look foretell the successful future of the young woman.

Nadezda Petrovic was born October 1873, died 3 April 1915, she was a Serbian painter and one of the women war photography pioneers in the region. Considered Serbia's most famous impressionist and fauvist, she was the most important Serbian female painter of the period. Born in the town of Cacak, Petrović moved to Belgrade in her youth and attended the women's school of higher education there. Graduating in 1891, she taught there for a period beginning in 1893 before moving to Munich to study with Slovenian artist Anton Azbe. Her works include almost three hundred oils on canvas, about a hundred sketches, studies and sketches, as well as several watercolors. Her works belong to the currents of secession, symbolism, impressionism and fauvism. Between 1901 and 1912, she exhibited her work in many cities throughout Europe.

Alice Bailly

Alice Bailly (1872-1938) was a Swiss artist who was born in Geneva in 1872 and lived a life that was both challenging and inspiring. Her father, who worked at the post office, passed away when she was a teenager, leaving her family to fend for themselves. Her mother, a teacher, did her best to provide for Alice and her siblings. Despite attending the Ecole des Demoiselles, Alice could only study women's courses, and it wasn't until she left school that she began to explore her passion for art.

Living next door to the School of Fine Arts in Geneva, Alice could not attend due to the restrictions placed on women at the time. Nonetheless, she persevered and continued to study art on her own. At the age of thirty-two, she moved to Paris, where she quickly made friends with several artists who shared her passion for creativity. Here, she discovered Fauvism, a bold and colorful artistic movement that often emphasized unrealistic and exaggerated imagery. This style resonated with Alice, and she embraced it wholeheartedly. During the First World War, Alice returned to Switzerland, where she created unique wool paintings using short pieces of colored yarn instead of brush strokes. These pieces were both innovative and highly sought after, and Alice quickly established herself as a respected artist in the Swiss art scene.

Alice regularly exhibited her work throughout her career, most notably at the Salon de Independents. This event was created to showcase the work of artists who didn't conform to traditional artistic standards and styles, making it a perfect platform for Alice to showcase her unique vision. It was also a place where female artists could exhibit their work, and Alice was proud to be a part of this movement toward gender equality in the arts.

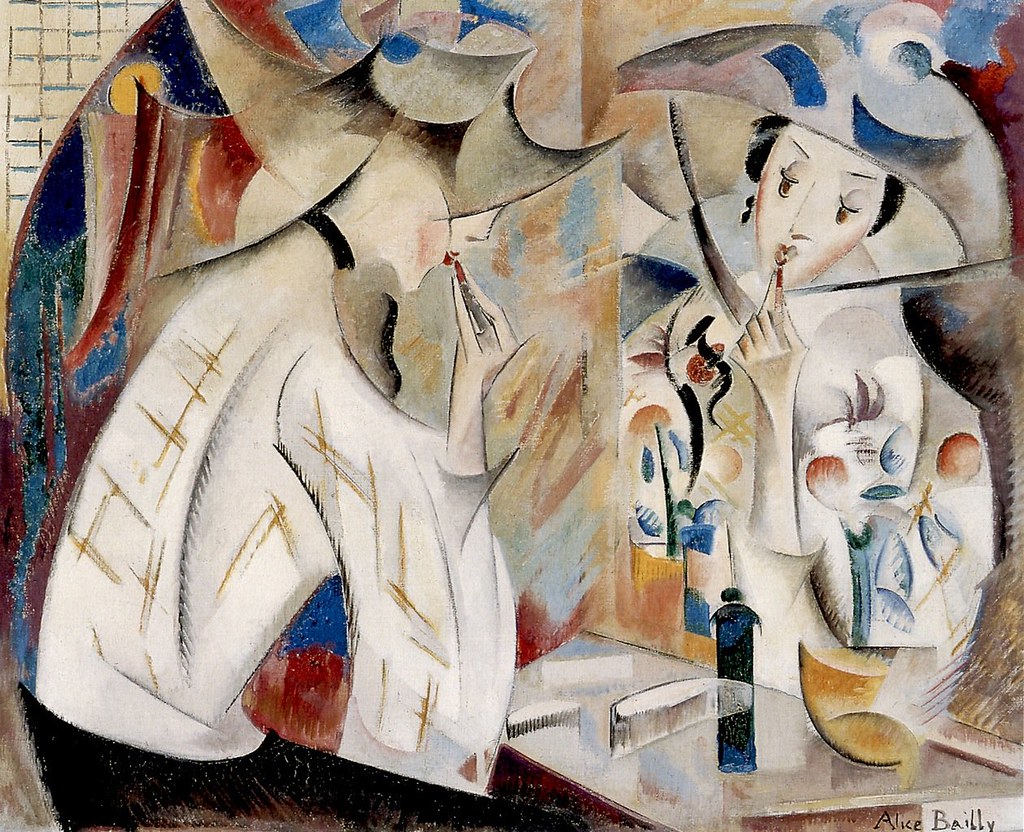

Bailly's Self-portrait (7.2.5) certainly did not meet the standards of the time and was considered too avant-garde. Her body position of a three-quarter-turn met the standard for posing. However, the rest of the portrait was considered very unconventional with its bright colors and distorted face, neck, and arms. Bailly used red on both sides of the figure, highlighting the paler skin and clothing. She is holding an excessively long and thin brush in her hand. Bailly created different versions of the Woman in Front of a Mirror (7.2.6). In this image, Bailly incorporates Cubism concepts, particularly in the woman's hat. The mirror reflection shows a complete hat while the woman's hat appears pieced together. The jacket and arm have unusual shapes, and the jacket shape of the woman in the mirror differs from the actual woman. Bailly also uses reflections on the shelf to add depth to the comb and other items on it. Additionally, she employs dark, bold lines of Fauvism to create unrealistic space and anatomy in both images.

Maria Magdalena Laubser

Maria Magdalena Laubser (1886-1973), a renowned artist, is credited with introducing Expressionism to South Africa and later incorporating the Fauvism style into her artwork. Born in Swartland, South Africa, which is a significant agricultural region, Laubser developed a keen interest in drawing during her time at boarding school. In 1913, she embarked on a journey to Europe to pursue her passion for art and further hone her skills.

Upon her return to South Africa in 1924, Laubser's work was subjected to criticism by the local press for being too modern. However, her artwork was well-received in England, where she gained recognition for her innovative style. By 1936, she was featured in The Empire Exhibition, one of the most significant expositions held every four years in the British Empire's territory. Laubser's work was highly praised, and she was hailed as one of the most exceptional artists from South Africa. Despite facing criticism in her homeland, Laubser remained dedicated to her art and continued to enjoy success as an artist throughout her life. Her work received numerous awards, which served as a testament to her exceptional talent and unwavering commitment to her craft. Maria Magdalena Laubser's contribution to the art world is remarkable, and her legacy continues to inspire artists worldwide.

Laubser used bright colors unconventionally that were not accepted in the then highly segregated and conservative South Africa. Some said her work was childlike and simplistic. Portrait of a Man (7.2.7) demonstrates Laubser's use of exaggerated color. The man's face is divided into different planes of blue and red hues. His hand hangs in the foreground and conflicts with the staring eyes for the viewer's attention. The man's elbow appears to rest on the shelf; however, a close examination shows the elbow in the air. The background red frame also sits at an angle, a position not found in ordinary portraits. Annie of the Royal Bafokeng (7.2.8) is a portrait of a young woman from the Bafokeng Nation. Laubser used bright colors in the painting, especially her neon yellow head covering. The oversized red flowers native to South Africa fill the top half of the painting and are reflected in the design of the woman's dress. Adding a mountainous landscape in the background moved the woman and the flowers into the foreground. Laubser used blue throughout the entire painting and contrasting red and yellow to bring drama to the painting.

%252C_oil_on_board%252C_595_x_475_mm.jpg?revision=1)

[1] Chilvers, I., (2004). Oxford Dictionary of Art, Oxford University Press, p. 250.

[2] Perry, G. (1995). Women Artists and the Parisian Avant-Garde. Manchester University Press, p. 100. Retrieved from https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89milie_Charmy