3.2: European Medieval Art (500 CE - 1400 CE)

- Page ID

- 183174

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Introduction

The Medieval, also known as the Middle Ages period in Europe, was bounded by the fall of the Roman Empire. It leads to the beginning of the Renaissance art period in Europe. At this time, Christianity was established as the primary religion bringing specific ideals and ecclesiastical standards. The fragments from the Roman Empire defined the boundaries of many European countries. The countries developed a political system based on the monarchy, a ruler empowered by heredity. Most people were farmers who lived in small rural villages. Women were primarily responsible for childcare, food preparation, tending livestock, and helping at harvest time to gather crops. Women who lived in the larger towns were responsible for childcare and food preparation. They also helped their father or husband in the many trades and crafts needed to support city life, including creating textiles, leather goods, or different metal objects or managing shops and inns.

In this period, the beliefs and teachings of the Catholic church generally informed people's lives. Biblical readings reflected in medieval art frequently portrayed Eve as responsible for leaving paradise, generating the long-held belief that women were weaker than men, easily tempted to sin, and inferior to men. Based on this story and other biblical tales, men's authority over women was emphasized, teaching women to be submissive. Biblical stories about the Virgin Mary became the elevated image of a woman as a powerful model of virtue and motherhood. All types of art forms were based on the ideas of Mary. The few places women could have power were to be a queen, regent to the throne, or the abbess of a convent. Most women had little control over their lives, and even women of privilege were forced into arranged marriages. A woman could marry or become a nun and live forever in a monastery to pray and work.

Visual arts, generally based on religious concepts, dominated artistic values. Unlike today's art, the concept of European medieval art was based on the ideas of theory and doctrine. It wasn't until later that artists became interested in their individuality. Medieval art was functional and an elevation of God and the church. The ruling class and the church commissioned most of the art seen in cathedrals, manuscripts, paintings, and sculptures. Very little identifiable art created by women is known today. Although men dominated art, the nuns lived in isolation and produced illuminated manuscripts that still survive today. Nuns were transformed when entering the convent, leaving their previous life and name behind and adopting a new name. In the convent, a woman was taught to read and write, and copying biblical passages was considered a privilege. Most illuminated manuscripts are anonymous because the nun's vows prevented her from using a name on her work. One exception was for the convent abbess or prioress as the leader and the permission to sign her name.

- Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179)

- Herrad of Landsberg (c. 1130-1195)

- Ende (10th century)

- Sibilla von Bondorf (c. 1440-1525)

- Claricia (or Clarica) (13th century)

- Guda (Guta) (12th century)

- Gunnborga (11th century)

- Bayeux Tapestry (11th century)

Hildegard of Bingen

Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) was born in Germany. Her family name was unknown, although early writers did note the family was wealthy. She suffered from poor health as a child, with trouble walking and seeing. Hildegard entered the convent and learned to read, write and sing religious psalms as part of her spiritual training. Even as a child, Hildegard believed she had visions of the future. When she related the visions to others, they did not believe her, and she learned to keep the concepts to herself. When Hildegard was almost forty years old, she was told by a superior to write about her visions. People began to believe the messages in Hildegard's writings and came from all parts of the country to hear her speak. Hildegard's works included medical information, visionary messages, and philosophical theories. She became a well-known composer of sacred music, and more of Hildegard's liturgical chants have survived than any other medieval composer. Hildegard wrote letters and poems, doing her extensive writings into illuminated manuscripts.

Scivias was the first of Hildegard's illuminated manuscripts she created about her religious visions. She divided the manuscript into three sections based on her concept of the Trinity. Part one included how she was instructed to compose the work and six different visions. The second part dealt with personal salvation through the church's teachings, and the third section described her visions about good and evil and the kingdom of God. Hildegard also included songs she thought of as the voice of heaven. It is unclear if she produced the illustrations or only made sketches of the visions and had others complete the images. At the beginning of each section, Hildegard opened with a prophetic statement. In the first section, she wrote, "I heard again the voice from heaven speaking to me"; in section two, "And again I heard a voice from the heavenly heights speaking to me," and in section three, "And I heard that light who sat on the throne speaking."[1]

The frontispiece of Scivias (3.2.1) is the image of Hildegard receiving the heavenly vision as she sketches the visions on the wax tablet. Volmar, one of her teachers, is watching her work. The visions are the focal point with a direct line down from above, into her head, down her arm, and onto the tablet. The Choir of Angels (3.2.2) is one of the illustrations of her twenty-six visions. The illumination is made with inks and gold leaf. The angels form concentric circles around God according to their defined hierarchy. The first sphere was the seraphim and cherubim, closest to God. As part of the first section, Hildegard wrote the music inspired by her visions. Her music was from the 12th century and is still used in religious ceremonies. The video is a short selection of her music.

Herrad of Landsberg

Herrad of Landsberg (c. 1130-1195) was the Abbess of Hohenburg, a convent in eastern France. She was born into a noble family and entered the abbey when she was young. Many girls and women were from wealthy families and received a broader education than most young girls. As Herrad grew older, she rose within the abbey, eventually becoming the abbess. At first, she worked to rebuild the abbey and incorporate more of the surrounding land under the abbey's jurisdiction. As the abbess for twenty-eight years, she was well-liked both inside and outside the abbey and could maintain the support of the secular world.

About 1159, Herrad started her well-known work and was thought to be the first encyclopedia written by a woman, Hortus deliciarum (Garden of Delights). The illuminated manuscript covered the known sciences and literature and was reported to teach the convent women about the biblical and moral ideals of the sciences. The manuscript was immense, with 648 pages on 324 parchment sheets.[2] The manuscript was written in Latin with notes in German. Over 300 illustrations decorated the text, representing historical, theological, and literary themes. The manuscript was based on knowledge existing in the 12th century with poems and texts from classical writers. Hell (3.2.3) is a religious expression of hell and the horrors of humankind who permanently reside in hell. The black background emphasizes the red tongues of fire, as devilish creatures tormented each person. Terrifying images representing hell were familiar in medieval Christian art. Philosophy and the Seven Liberal Arts (3.2.4) differ in looks and spirit. The light background is decorated with colorfully dressed people in the outer ring, each representing the seven liberal arts: Grammar, Logic, Rhetoric, Geometry, Arithmetic, Astronomy, and Music. The seven categories were defined in the late Roman period and used for medieval European education. Philosophy sits in the center as a queen with Socrates and Plato at her feet, the long scroll stating, "All wisdom comes from God. Only the wise can do what they will."[3]

Ende

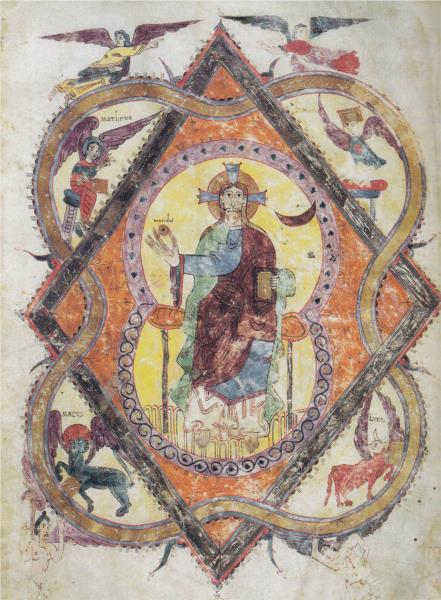

Ende (10th century) was the first known Spanish female to work on illuminated manuscripts and was believed to be a nun. Her work was identified by the signature "pintrix et D[e]I aiutrix (paintress and helper of god)."[4]Ende's work is seen in the illuminated manuscript Gerona Beatus. How much of the illustrated work was done by Ende is still debated; however, some historians believe most of the work was accomplished by her. The Gerona Beatus had two specific sections, Commentary on the Apocalypse, the manuscript written by Beatus of Liébana, and the Book of Daniel by Jerome. The illuminators were identified as Ende and the monk Emeterius.

The Last Judgment from the Gerona Beatus (3.2.5) demonstrates the concepts of the last judgment. The top half of the image shows the blessed rising towards the heavens while the sinful in the bottom half are descending into the horrors of hell. Those damned to hell are shackled as they fall while those going to heaven move towards the light. Maiestas Domini (3.2.6) features the image of Christ seated on a throne as he holds a gold disk in one hand and a closed gold book in his left hand. He is outlined by a sizeable quadrangular shape intersected with a rhombus. The evangelists, Mathew, Mark, Luke, and John, are represented, each facing the Christ image as they also hold a golden book. Each page is very detailed and uses color to define the spirit, feeling, and emotion.

_002.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=567&height=786)

Sibilla von Bondorf

Sibilla von Bondorf (c. 1440-1525) was a nun in a Clarissan convent in Germany. Much of von Bondorf's work was for prayer books or books used in the liturgy. Her primary work was a set of illustrations based on the lives of Saint Francis, Saint Clara, and Saint Elisabeth. Copies of her work were widely used among other convents. The full-page illustrations by von Bondorf included 52 for Saint Francis, 33 for Saint Clara, and 14 for Saint Elisabeth. Religious changes in Germany in the 1400s brought opportunities for women in convents to create and produce manuscripts and liturgical books. Although von Bondorf was not a trained artist, she mastered using line, color, and design. She developed perspective in her work by using patterns to delineate and unify the image's foreground and background. In one of the pages from the images of Saint Francis (3.2.7), von Bondorf uses bright colors and gold. The rug is highly patterned and anchors the bottom of the image. Saint Francis is standing on a chair, preaching to those who are opening their minds to his word. Von Bondorf used patterns extensively on the red-leaved background, the wood-grain door, and the elegant halos.

Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\): Page from The Story of Saint Francis (Opaque pigments with gold and silver on parchment, 15 x 10 cm, c. 1460) (Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International)

Claricia

Claricia (or Clarica) was a German artist who illuminated manuscripts in the late 12th or early 13th century and was probably a nun in a Bavarian convent. Her most famous work was a German psalter (3.2.8) (a manuscript of the Psalms). The psalter was made on parchment with a large, elaborate letter Q. The tail of the Q is a self-portrait of Claricia swinging from the bottom of the letter with her name inscribed by her head. Scholars disagree on whether she was a nun or a high-born lady. One scholar believed her clothing, uncovered head, and braids indicate she was probably a lay student attending classes at the convent and working on manuscripts.

Guda

Guda (Guta) was born in Germany in the 12th century as a nun and illuminator. Guda was one of the first women to develop a self-portrait in a manuscript, opening the door for those women following her. Guda created her image set in an initial letter (3.2.9) for the manuscript based on the homilies of St. Bartholomew. She drew herself dressed as a nun and wrote, "Guda, a sinner, wrote and painted this book."[5] She described herself as a sinner and an artist and hoped to be saved. By creating the illustrated initial, Guda made a signature and identified herself as a scribe.

.jpeg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=458&height=445)

Gunnborga

Gunnborga (11th century) was from Sweden and was a runemaster. A runestone (3.2.10) was inscribed with a runic inscription based on the runic alphabet used by Germanic people in Northern Europe. Generally, the stone was raised and placed in specific places; some runestones were inscribed on boulders or bedrock. The inscriptions on the stone were brightly colored with paint. During Viking times in Sweden, runestones were carved and erected to depict people from Norse mythology. As Christianity increased, the runestone inscriptions had religious meanings. Gunnborga was the only female confirmed runemaster. The text on Hälsingland Rune Inscription 21, located by a church in Sweden, identified Gunnborga as the carver. The stone says, "Ásmundr and Farþegn erected this stone in memory of Þorketill of Vattrång, their father. Gunnborga the Good carved this stone."[6]

Bayeux Tapestry

Women in medieval times were also educated in embroidery and tapestry art, acceptable forms of art both in the home and the convent. Elite women did embroidery as a suitable occupation and pastime, while ordinary women embroidered for their families. Larger estates established workshops and hired local women, increasing production. By the time of the Norman conquest in 1066, there were many embroidery workshops in England, and English embroidery was famous throughout Europe.

The Bayeux Tapestry was based on England's conquest by William, Duke of Normandy, following the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The entire tapestry is seventy meters long. The images depict different stories and activities from the beginning of the battle, as the longships crossed the sea, to the installation of William on the throne. The immense work was commissioned in 1077 by Bishop Odo for the new cathedral in Bayeux. The tapestry tells the story of medieval England's ordinary people and the military. The details move from large castles to miniature helmets; everything is detailed in any scene. The large central panel is bordered by a small seven-centimeter border along the top, covered with real and imaginary animals. The bottom edge is filled with images of the dead from the battlefield scenes.

Although it is called a tapestry, the work was embroidered on nine linen panels joined together. The embroidery was made with wool thread using guide marks. Scholars believe the guide marks were originally basic drawings for the pattern. The pictures in the different sections were used to educate the illiterate people about the war, battles, and conquest, a sort of newspaper. The wool thread was hand-dyed using local plants. Woad was used for different shades of blue, and Dyer's rocket was made yellow. Madder produced various red tones, including orange, pink, and brown. The embroidery stitches used in the tapestry are still used today, including the stem, chain, and split stitches. The couching stitch is often named the Bayeux stitch and is used to fill solid areas.

The combatants portrayed in the tapestry are identified by their customs; the Anglo-Saxons had mustaches, and the Normans had the habit of shaving the back of their heads. Guy I, Count of Ponthieu (3.2.11) is a small section of the tapestry depicting the messengers meeting with the count. Guy took Harold prisoner, and William sent messengers to tell Guy to release Harold. The small border strip portrays the processes of medieval agriculture. The death of King Harold at the Battle of Hastings (3.2.12) is part of the scene when King Harold is slain at the Battle of Hastings. The title states HIC HAROLD REX INTERFECTUS EST (Here, King Harold is killed). The coronation of Harold II of England (3.2.13) displays Harold's coronation as king after King Edward's death. King Harold received the orb and scepter denoting his kingship as courtiers surrounded him. The outline of the castle covers the king on his throne.

A video outlining the masterpiece of embroidery in the Medieval Times.

[1] Flanagan, S. (1998). Hildegard of Bingen: A Visionary Life (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. Retrieved from https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Scivias

[2] Engelhardt, Christian Moritz (1818). Herrad von Landsperg, Aebtissin zu Hohenburg oder St. Odilien, im Elsaß, im zwölften Jahrhundert; und ihre Werk: Hortus deliciarum: ein Beytrag zur Geschichte der Wissenschaften, Literatur, Kunst, Kleidung, Waffen und Sitten des Mittelalters. Stuttgarts and Tubingen. Retrieved from https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Herrad_of_Landsberg

[3] Retrieved from https://liberalarts.online/philosoph...-liberal-arts/

[4] Retrieved from https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascf...age_floor/ende

[5] Women in the Making: Early Medieval Signatures and Artists' Portraits (9th–12th c.)", Reassessing the Roles of Women as 'Makers' of Medieval Art and Architecture, BRILL, pp. 393–427, 2012-01-01, doi:10.1163/9789004228320_012, ISBN 9789004228320. Retrieved from https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Guda_(nun)

[6] Retrieved from http://www.365womenartists.com/2018/...11th-cent.html