20.4: Architecture of the Northern Renaissance

- Page ID

- 53066

Chartreuse de Champmol

The Chartreuse de Champmol, a Carthusian monastery on the outskirts of Dijon, represents the finest monumental work of early modern France.

Learning Objectives

Discuss how the Carthusian monastery Chartreuse de Champmol became “the grandest project in a reign renowned for extravagance” under the Valois dynasty of Burgundy

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Champmol was intended to rival Cîteaux, Saint-Denis, where the Kings of France were buried, and other dynastic burial places.

- Champmol was lavishly enriched with works of art, and the dispersed remnants of its collection remain key to the understanding of the art of the period.

- The monastery was founded in 1383 by Duke Philip the Bold to provide a dynastic burial place for the Valois Dukes of Burgundy, and operated until it was dissolved in 1791, during the French Revolution .

- In 1395, Claes Sluter began work on the Well of Moses, which combines International Gothic with northern realism . However, the monumentality of the sculptures is unprecedented in either style .

- The interior of the church features the elaborate tombs of John the Fearless and Margaret of Bavaria, each of which is supported by a sculpture group of pleurants (mourners) whose expressions of grief are unprecedented for their time.

Key Terms

- Carthusian monastery: The building, or complex of buildings, comprising the domestic quarters and workplace(s) of monastics, whether monks or nuns, and whether living in community or alone (hermits). The monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer, which may be a chapel, church or temple, and may also serve as an oratory.

- Valois: A cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty, succeeding the House of Capet (or “Direct Capetians”) as kings of France from 1328 to 1589. A cadet branch of the family reigned as dukes of Burgundy from 1363 to 1482. They were descendants of Charles of Valois, the fourth son of King Philip III. They based their claim on the Salic law, which excluded females (Joan II of Navarre) as well as male descendants through the distaff line (Edward III of England), from the succession to the French throne.

Monastic Splendor

The Chartreuse de Champmol, formally the Chartreuse de la Sainte-Trinité de Champmol, was a Carthusian monastery on the outskirts of Dijon, which is now in France, but in the 15th century was the capital of the then-independent Duchy of Burgundy. The monastery was founded in 1383, by Duke Philip the Bold, to provide a dynastic burial place for the Valois Dukes of Burgundy, and operated until it was dissolved in 1791, during the French Revolution. It was lavishly enriched with works of art, and the dispersed remnants of its collection remain key to the understanding of the art of the period. Champmol was intended to rival Cîteaux, Saint-Denis, where the Kings of France were buried, and other dynastic burial places.

Purchase of the land and quarrying of materials began in 1377, but construction did not begin until 1383, under the architect Druet de Dammartin from Paris, who had previously designed the Duke’s chateau at Sluis, and worked as an assistant in the construction of the Louvre. A committee of counselors from Dijon supervised the construction for the often absent Duke. By 1388 the nearly completed church was consecrated. Claes Sluter and his workshop produced sculptures of Philip and his wife kneeling in prayer toward the central sculpture of the Madonna and Child for the church’s main portal .

The monastery was built for 24 choir monks, instead of the usual 12 in a Carthusian house. Its cloister surrounded a courtyard in which Sluter constructed the Well of Moses (1395–1403), whose monumental sculptures combine the International Gothic style with a northern realism. Their scale, however, is unprecedented in either style. The figures range from the namesake of the well to Old Testament prophets to the Crucifixion. Although it was intended to function as a fountain, the water feature was abandoned so as not to conflict with the monks’ vow of silence.

In 1433, two more monks were endowed to celebrate the birth of Charles the Bold. These lived semi-hermitic lives in their individual small houses when not in the chapel. Other inhabitants of the monastery included non-ordained monks, servants, novices, and other workers.

A Ducal Symbol

Somewhat in contradiction to the Carthusian mission of tranquil contemplation, the monastery welcomed visitors and pilgrims. The expenses of hospitality were then recompensed by the Dukes. In 1418, Papal indulgences were granted to those visiting the Well of Moses, further encouraging pilgrims. The Ducal family had a private oratory overlooking the church, which has since been destroyed, though their visits were in fact rare. Ducal accounts show major commissions for paintings and other works to complete the monastery continuing until about 1415. Further works were later added by the Dukes and other donors, although building progressed at a slower rate.

The Valois dynasty of Burgundy had less than a century to run when the monastery was founded. The number of Valois tombs never approached that of their Capetian predecessors at Cîteaux, as the choir of the church was not large enough to accommodate them. Only two monuments were ever erected, both in the same style, with painted alabaster effigies with lions at their feet and angels with spread wings at their heads. Underneath the slab on which the effigies rested, small unpainted pleurants (mourners) were set among Gothic tracery . They were, at the time of their production, the most moving representations of grief conveyed in a sculptural medium .

Pleurants (Mourners): Stone mourners at a tomb in Chartreuse de Champmol. Approximately 40 cm high.

Tomb of John the Fearless and Margaret of Bavaria: John the Fearless commissioned work on this tomb, though by his death in 1419, nothing had been done. The project saw several different artists at work until its completion in 1470.

Champmol was designed as a showpiece. The artistic contents, now dispersed, represent much of the finest monumental work of French and Burgundian art of the period, demonstrating a tradition distinct from that of the similarly prestigious illuminated manuscripts .

French Architecture in the Northern Renaissance

Francis I (1515–1547) brought about such huge cultural changes in France that he has been called France’s original Renaissance monarch.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the advancements in architecture as seen under the reign of Francis I

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- At the time of the accession of Francis I, the royal palaces of France were ornamented with only a scattering of great paintings and devoid of sculpture. During his reign, the magnificent art collection of the French kings was begun.

- Francis poured vast amounts of money into new structures. He continued the work of his predecessors on the Château d’Amboise and also started renovations on the Château de Blois. Early in his reign, he also began construction of the magnificent Château de Chambord.

- Not a castle in the traditional military sense, the Château de Chambord was built as a hunting lodge for the king and contains unique architectural elements, such as towers without turrets and a double spiral staircase that extends through three stories.

- The largest building project under Francis’s reign was at the Palace of Fontainebleau, where, it is said, the French Renaissance began.

- Francis employed some of the most famous artists from Europe to decorate Fontainebleau. They included Rosso Fiorentino, Francesco Primaticcio, and Benvenuto Cellini. Cellini designed the famous Nymphe de Fontainebleau.

Key Terms

- patron: An influential, wealthy person who supports an artist, craftsman, scholar, or aristocrat.

- château: French castle, fortress, manor house, or large country house.

Francis I: Patron of the Arts

Francis I (1494–1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death. During his reign, huge cultural changes took place in France. He has been called France’s original Renaissance monarch. By the time he ascended the throne in 1515, the Renaissance had arrived in France, and Francis became a major patron of the arts. At the time of his accession, the royal palaces were ornamented with only a scattering of great paintings and no sculptures. During Francis’s reign, the magnificent art collection of the French kings, which can still be seen at the Louvre, was begun.

Francis I by Jean Clouet (circa 1530): Portrait of Francis I. He was one of the great patrons of the arts in early modern Europe.

Francis poured vast amounts of money into new structures. He continued the work of his predecessors on the Château d’Amboise and also started renovations on the Château de Blois. Early in his reign, he began construction of the magnificent Château de Chambord, inspired by the styles of the Italian Renaissance and perhaps even designed by Leonardo da Vinci. Francis rebuilt the Château du Louvre, transforming it from a medieval fortress into a building of Renaissance splendor. He financed the building of a new City Hall (Hôtel de Ville) for Paris in order to have control over the building’s design. He constructed the Château de Madrid in the Bois de Boulogne and rebuilt the Château de St-Germain-en-Laye.

Châteaux in the 16th century departed from castle architecture. While they were offshoots of castles, with features commonly associated with them, they did not have serious defenses. Extensive gardens and water features, such as a moat, were common amongst châteaux from this period.

The Francis I wing of the Chateau de Blois: The Château de Blois’s spiral staircase is one of the great artistic achievements of the French Renaissance under Francis I.

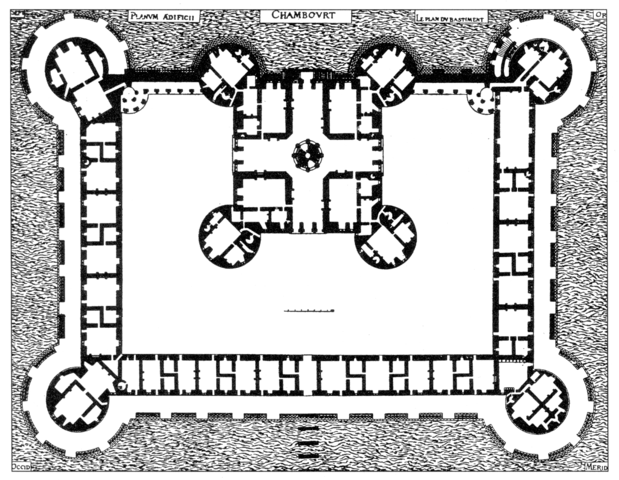

Château de Chambord

Chambord is the largest château in the Loire Valley. It was built primarily as the king’s hunting lodge. The layout is reminiscent of a typical castle with a keep , corner towers, and defended by a moat. Built in Renaissance style, the internal layout is an early example of the French and Italian style of grouping rooms into self-contained suites, a departure from the medieval style of corridor rooms. The massive château is composed of a central keep with four immense bastion towers at the corners. The keep also forms part of the front wall of a larger compound with two more large towers. Bases for a possible further two towers are found at the rear, but these were never developed, and remain the same height as the wall. The château features 440 rooms, 282 fireplaces, and 84 staircases. Four rectangular vaulted hallways on each floor form a cross shape.

Like the Château de Blois, one of Chambord’s architectural highlights is the spectacular open double spiral staircase. The two spirals ascend the three floors without ever meeting, illuminated from above by a sort of lighthouse at the highest point of the château.

Château of Fontainebleau

The largest of Francis’s building projects was the reconstruction and expansion of the royal Château of Fontainebleau, which quickly became his favorite place of residence, as well as the residence of his official mistress (Anne, Duchess of Étampes). He commissioned the architect Gilles le Breton to build a château in the new Renaissance style. Le Breton preserved the old medieval donjon, where the king’s apartments were located, but incorporated it into the new Renaissance style Cour Ovale (Oval Courtyard), built on the foundations of the old castle. It included monumental Porte Dorée (Golden Door), the main entrance, as its southern entrance, as well as a monumental Renaissance stairway, the portique de Serlio, to give access the royal apartments on the north side.

Beginning in approximately 1528, Francis constructed the Gallery Francis I, which allowed him to pass directly from his apartments to the chapel of the Trinitaires. He brought the architect Sebastiano Serlio from Italy, and the Florentine painter Giovanni Battista di Jacopo, known as Rosso Fiorentino, to decorate the new gallery. Between 1533 and 1539 Rosso Fiorentino filled the gallery with murals glorifying the king, framed in stucco ornament in high relief , and lambris sculpted by the furniture maker Francesco Scibec da Carpi. Another Italian painter, Francesco Primaticcio from Bologna, joined later in the decoration of the château. Together their style of decoration became known as the first School of Fontainebleau. This was the first great decorated gallery built in France. Broadly speaking, at Fontainebleau the Renaissance was introduced to France.

Each of Francis’s projects was luxuriously decorated, both inside and out. Fontainebleau, for instance, had a gushing fountain in its courtyard where quantities of wine were mixed with the water. The fountain was linked to a legend related to one of the best known projects for the château.

Among the most striking works of art within Fontainebleau was the Nymphe de Fontainebleau (1542) by the Italian sculptor Benvenuto Cellini. Francis commissioned this large-scale bronze bas relief , cast in the lost wax process, as the tympanum to sit atop the Porte Dorée. In the sculpture, a Mannerist nude nymph reclines among woodland animals, such as deer and boars. The central buck, wearing a garland of fruit, symbolizes Francis’s power. As a whole the sculpture is based on a legend in which a hunting dog discovered a spring personified by a nymph learning against an urn . It was this spring that gave the château and surrounding environs the name Fontainebleau. The tympanum was to be flanked on either side by bronze sculptures of nude satyrs , posed as mirror images of one another, also cast by Cellini. Eventually, the project was abandoned, and the nymph was integrated into the design of an aristocrat’s palace 10 years later.

Spanish Architecture in the Northern Renaissance

Gothic, Renaissance, and Mannerist elements are all important to the architecture of Spain in the 16th century.

Learning Objectives

Examine the influence of Gothic, Renaissance, and Mannerist elements in the architecture of Spain in the 16th century

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Plateresque emerged in Spain in the late 15th century. This architectural style , named for silversmiths, was known for producing decorative façades suggestive of silver plate.

- From the mid 16th century, Spanish architecture adhered closely to the art of ancient Rome , anticipating Mannerism .

- The Herrerian style dominated Spain in the late 16th and 17th centuries and was defined by clean and sober façades and attention to geometrical precision.

- El Escorial is a well-known example of the Herrerian style with its austere façades and fortress-like appearance.

Key Terms

- Herrerian: A 16th century Spanish style characterized by geometric rigor, clean volumes, the dominance of the wall over the span, and the almost total absence of decoration.

- plateresque: Pertaining to an ornate style of architecture of 16th century Spain suggestive of silver plate.

Renaissance architecture reached the Iberian peninsula in the 16th century, ushering in a new style that gradually replaced the Gothic architecture , which had been popular for the centuries.

Gothic forms began to incorporate the classical style of the Renaissance in the last decades of the 15th century. Local architects developed a specifically Spanish Renaissance, bringing the influence of South Italian architecture, sometimes from illuminated books and paintings, mixed with Gothic tradition and local traditions. The new style was called Plateresque because of the extremely decorated façades that brought to the mind the decorative motifs of the intricately detailed work of silversmiths, the “Plateros.” Ornamentation included floral designs, chandeliers, festoons, fantastic creatures, and similar configurations. The spatial arrangement of Plateresque, however, is more clearly Gothic-inspired. This fixation on specific parts and their spacing, without structural changes of the Gothic pattern, causes it to be often classified as simply a variation of Renaissance style. A prime example of this decorative style can be seen in the façade of the University of Salamanca.

From the mid 16th century, under architects such as Pedro Machuca, Juan Bautista de Toledo, and Juan de Herrera, there was a much closer adherence to the art of ancient Rome, sometimes anticipating Mannerism. An example of this is the palace of Charles V in Granada built by Pedro Machuca.

A new style emerged in Spain with the work of Juan Bautista de Toledo and Juan de Herrera in El Escorial, known as the Herrerian style. Herrerian architecture was extremely sober, naked, and particularly accomplished in the use of granite ashlar work. This style influenced the Spanish architecture of both the peninsula and the colonies for over a century.

Monasterio de Uclés, Cuenca, España: The Monastery of Uclés is a prime example of Herrerian architecture.

The floor plan of El Escorial—a palace for the royal family, monastery for their clergy, and burial place for major Spanish monarchs—was designed in the form of a gridiron. It was a design whose origin remains a matter of debate.

Regardless of the reasons behind the floor plan, its basic components, as well as the general exterior and main façade, conform to the austerity of the Herrerian style, making the structure appear more like a fortress than a palace or monastery. It takes the form of a gigantic quadrangle, which encloses a series of intersecting passageways and courtyards and chambers. At each of the four corners is a square tower surmounted by a spire and near the center of the complex rise the pointed belfries and round dome of the basilica , which are and taller than the rest. As overseer of the construction of El Escorial, Philip II instructed his architects to maintain a sense of simplicity.

The austerity of the west façade of El Escorial is typical of the classicism that re-emerged during the Renaissance. However, the main entrance, which takes the form of classical temple façades stacked atop another, actually looks forward to an architectural design that would become common during the Baroque era throughout Europe.

English Architecture in the Northern Renaissance

The Tudor architectural style was the final development of medieval architecture during the Tudor period (1485–1603).

Learning Objectives

Describe the key elements of the Tudor architectural style, including the Tudor arch, oriel windows, and the chimney stack

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Tudor architecture followed the Perpendicular style and, although superseded by Elizabethan architecture in the domestic building of any pretensions to fashion, the Tudor style still retained its hold on English taste.

- The four-centered arch , now known as the Tudor arch , was a defining feature of the period. It was often used in the construction of large lancet style windows.

- Another common feature of Tudor architecture was the oriel window and the jetty , both defined by their projection from the main part of the building.

- During this period, the arrival of the chimney stack and enclosed hearths resulted in the decline of the great hall based around an open hearth, which was typical of earlier medieval architecture.

- During the Tudor era, houses and buildings of ordinary people were typically timber -framed, the frame usually filled with wattle and daub but occasionally with brick.

Key Terms

- Perpendicular style: The third historical division of English Gothic architecture, so called because of its emphasis on vertical lines.

- Tudor arch: Low and wide with a pointed apex, much wider than its height and appearing to have been flattened under pressure.

- jetty: A building technique used in medieval timber-frame buildings in which an upper floor projects beyond the dimensions of the floor below.

- oriel: A form of bay window that projects from the main wall of a building but does not reach to the ground.

- Elizabethan: Pertaining to the reign of first female monarch of England.

The Tudor architectural style was the final development of medieval architecture during the Tudor period (1485–1603), and even beyond, for conservative college patrons . The designation “Tudor style” is an awkward one, with its implied suggestions of continuity through the period of the Tudor dynasty and the misleading impression that there was a style break at the accession of Stuart James I in 1603. It followed the Perpendicular style and, although superseded by Elizabethan architecture in the domestic building of any pretensions to fashion, the Tudor style still retained its hold on English taste. Portions of the additions to the various colleges of Oxford University and Cambridge University were still being carried out in the Tudor style, which overlaps with the first stirrings of the Gothic Revival.

The Tudor arch, a low and wide type of arch with a pointed apex , was a defining feature of the period. It is much wider than its height and gives the visual effect of having been flattened under pressure. This type of arch, when employed as a window opening, lends itself to very wide spaces , as seen in the chapel window of King’s College at Cambridge University.

King’s College chapel, University of Cambridge: The chapel at King’s College of the University of Cambridge is one of the finest examples of late Gothic (Perpendicular) English architecture, while its early Renaissance rood screen (separating the nave and chancel), erected in 1532–36 in a striking contrast of style, shows the influence of architecture from the Italian peninsula.

Some of the most remarkable oriel windows belong to this period. An example can be seen in the Priory Church of St. Bartholomew the Great in London. The oriel window was installed inside St. Bartholomew the Great in the early 16th century by Prior William Bolton, allegedly so that he could keep an eye on the monks. The symbol in the center panel is a crossbow “bolt” passing through a “tun” (or barrel), a pun on the name of the prior.

During this period, the arrival of the chimney stack and enclosed hearths resulted in the decline of the great hall based around an open hearth, which was typical of earlier medieval architecture. Instead, fireplaces could now be placed upstairs, and it became possible to have a second story that ran the whole length of the house. Tudor chimney pieces were made large and elaborate to draw attention to the owner’s adoption of this new technology. The jetty appeared as a way to show off the modernity of having a complete, full-length upper floor.

The style of large houses moved away from the defensive architecture of earlier moated manor houses, and instead began emphasizing aesthetics . For example, quadrangular (‘H’ or ‘E’ shaped plans) became more common. It was also fashionable for these larger buildings to incorporate “devices,” or riddles, designed into the building, which served to demonstrate the owner’s wit and to delight visitors. Occasionally these were Catholic symbols, for example, subtle or not-so-subtle references to the trinity, seen in three-sided, triangular, or ‘Y’ shaped plans, designs, or motifs .

The houses and buildings of ordinary people were typically timber-framed, the frame usually filled with wattle and daub but occasionally with brick. These houses were also slower to adopt the latest trends and the great hall continued to prevail. The Dissolution of the Monasteries provided surplus land, resulting in a small building boom, as well as a source of stone.

Anne Hathaway’s Cottage is a 12-room farmhouse where the wife of William Shakespeare lived as a child in the village of Shottery, Warwickshire, England. As in many houses of the period, it has multiple chimneys to spread the heat evenly throughout the house during winter. The largest chimney was used for cooking. It also has visible timber framing, typical of vernacular Tudor architecture.

Anne Hathaway’s Cottage: The design of the childhood home of Anne Hathaway is typical of a house inhabited by commoners in Tudor England.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Dijon-Palais-Gisant-Detail. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dijon-Palais-Gisant-Detail.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 640px-Dijon_mosesbrunnen2.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=763389. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Dijon - Tombeau des ducs de Bourgogne 1. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dijon_-_Tombeau_des_ducs_de_Bourgogne_1.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 640px-Dijon_-_Chartreuse_de_Champmol_-_Portail_1.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2758448%20. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Champmol.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5505613. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Well of Moses. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Well_of_Moses. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Champmol. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Champmol. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Carthusian Monastery. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Carthusian%20monastery. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Philip the Bold. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip%20the%20Bold. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Valois. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Valois. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- France Loir-et-Cher Blois Chateau 05. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:France_Loir-et-Cher_Blois_Chateau_05.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 640px-Chateau_de_Fontainebleau_Cour_ovale.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11713096. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Francis1-1. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Francis1-1.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 360px-Escalier_double_helice_Chambord.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=445927. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 640px-Chu00e2teau_de_Fontainebleau_2011_(262).jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16668144%20. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 640px-Nymphe_de_Fontainebleau.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23381123. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 640px-Chambord_Castle_Northwest_facade.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22654063. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 619px-ChambordGrundriss.png. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2178228. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Chu00e2teau de Blois. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ch%C3%A2teau_de_Blois. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Nymphe de Fontainebleau. Provided by: Wikipedia (France). Located at: fr.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Nymphe_de_Fontainebleau. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chu00e2teau de Chambord. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ch%C3%A2teau_de_Chambord. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Palace of Fontainebleau. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Palace_of_Fontainebleau#The_Renaissance_Ch.C3.A2teau_of_Francis_I_.281528.E2.80.931547.29. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Francis I of France. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_I_of_France. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Patron. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/patron. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Francis I. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis%20I. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chateau. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/chateau. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 640px-Facade_monastery_San_Lorenzo_de_El_Escorial_Spain.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21879649. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 334px-University_of_Salamanca.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=39607. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Herrerian. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Herrerian. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 640px-Vista_aerea_del_Monasterio_de_El_Escorial.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6581920%20. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 471px-Escorial_traza_def.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2945873. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- El Escorial. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/El_Escorial. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Architecture of the Spanish Renaissance. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Architecture_of_the_Spanish_Renaissance. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Plateresque. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/plateresque. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Herrerian. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Herrerian. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- KingsCollegeChapel. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:KingsCollegeChapel.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 640px-LittleMoretonHall.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=942415. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 360px-Prior_Bolton_Oriel_Window.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7066809. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 620px-Anne_Hathaways_Cottage_1_(5662418953).jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21108259. License: CC BY: Attribution

- English Gothic Architecture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Gothic_architecture#Perpendicular_Gothic. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Oriel Window. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Oriel_window. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- St. Bartholomew the Great. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Bartholomew-the-Great. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Anne Hathaway's Cottage. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Anne_Hathaway%27s_Cottage. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Perpendicular Style. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Perpendicular%20style. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tudor Architecture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tudor_architecture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Elizabethan. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Elizabethan. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Tudor Arch. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Tudor%20arch. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike