20.3: Books of the Northern Renaissance

- Page ID

- 53065

Illuminated Manuscripts

During the early to mid 1400s, illuminated books were considered a high art form, and Burgundy (Flanders) was a center of such production.

Learning Objectives

Examine the market for illuminated manuscripts in northern Europe during the Gothic period and how it changed

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Illuminated manuscripts included religious works such the books of hours and prayer books, but also histories, tales of adventure and love, poetry, and a wide range of moralizing works that we might classify as self-improvement books today.

- By the 14th century, the production of luxury manuscripts by monks writing in the monastic scriptorium had almost fully given way to commercial urban scriptoria, especially in Paris, Rome , and Burgundy.

- At the time illuminated manuscripts were considered treasured works of high craft; to own books indicated wealth, status, and taste. In addition books were commonly used as diplomatic gifts or as offerings to commemorate dynastic marriages.

- In the 1440s the cities of Bruges and Ghent became the most important centers of production of illuminated manuscripts, in part due to the patronage of the cultured Philip the Good , who by his death had collected over 1,000 individual books.

- Simon Marmion was perhaps the best known and most successful artist specializing in this area, although van Eyck is thought to have contributed to the “Turin-Milan Hours” as the anonymous artist known as Hand G.

Key Terms

- scriptoria: Rooms set aside for the copying, writing, or illuminating of manuscripts and records, especially in monasteries.

- illuminated manuscript: A book in which the text is supplemented by the addition of decoration, such as decorated initials, borders (marginalia), and miniature illustrations.

- Simon Marmion: Born c. 1425 at Amiens, France, died 24 or 25 December 1489, Valenciennes. A French or Burgundian Early Netherlandish painter of panels and illuminated manuscripts. Marmion lived and worked in what is now France but for most of his lifetime was part of the Duchy of Burgundy in the Southern Netherlands.

- Philip the Good: July 31, 1396–June 15, 1467. Philip was Duke of Burgundy from 1419 until his death. He was a member of a cadet line of the Valois dynasty (the then Royal family of France). During his reign Burgundy reached the height of its prosperity and prestige and became a leading center of the arts.

Illumination in a Gothic World

The Gothic period, which generally saw an increase in the production of illuminated manuscripts, also saw more secular works such as chronicles and works of literature illuminated. Wealthy people began to build up personal libraries. Philip the Bold probably had the largest personal library of his time in the mid-15th century; he is estimated to have had about 600 illuminated manuscripts, while a number of his friends and relations had several dozen.

Monastic Production of Luxury Books

During the early to mid 1400s, illuminated books were considered a higher art form than panel painting. While they had traditionally been created in monasteries, by the 12th century levels of demand led to their production in specialist workshops known in French as libraires. The works included religious works such the books of hours and prayer books, but also histories, tales of adventure and love, poetry, and a wide range of moralizing works that we might classify as self-improvement books today.

Urban Scriptoria

By the 14th century, the production of luxury manuscripts by monks writing in the monastic scriptorium had almost fully given way to commercial urban scriptoria, especially in Paris, Rome, and Burgundy. While the process of creating an illuminated manuscript did not change, the move from monasteries to commercial settings was a radical step. Demand for manuscripts grew to such an extent that the monastic libraries were unable to meet with the demand, and began employing secular scribes and illuminators. These individuals often lived close to the monastery and, in certain instances, dressed as monks whenever they entered the monastery, but were allowed to leave at the end of the day. In reality, illuminators were often well-known and acclaimed and many of their identities have survived.

At the time illuminated manuscripts were considered treasured works of high craft; to own books indicated wealth, status, and taste. In addition, they became common as diplomatic gifts, or offerings to commemorate dynastic marriages. Paris was the major source of supply after their production spread from the monasteries. However, its importance was supplanted in the 1440s by the cities of Bruges and Ghent, in part due to the patronage of the cultured Philip the Good, who by his death had collected over 1,000 individual books. When in the early to mid-15th century manuscripts were held in higher regard than panel paintings, masters would often produce single leaf illustrations to be almost randomly inserted into precious books, as a means for the master to display and advertise his skill.

Outstanding Illuminators

Simon Marmion was perhaps the best known and most successful artist specializing in this area, although van Eyck is thought to have contributed to the Turin-Milan Hours as the anonymous artist known as Hand G. A number of illustrations from the period show a strong stylistic resemblance to the work of Gerard David, though it is unclear whether they are by his hand or by his followers. There was considerable overlap between panel painting and illumination, and by the second half of the century large manuscript commissions were often shared between several different masters, with more junior painters, including many women, assisting, especially in producing the increasingly elaborate border decoration.

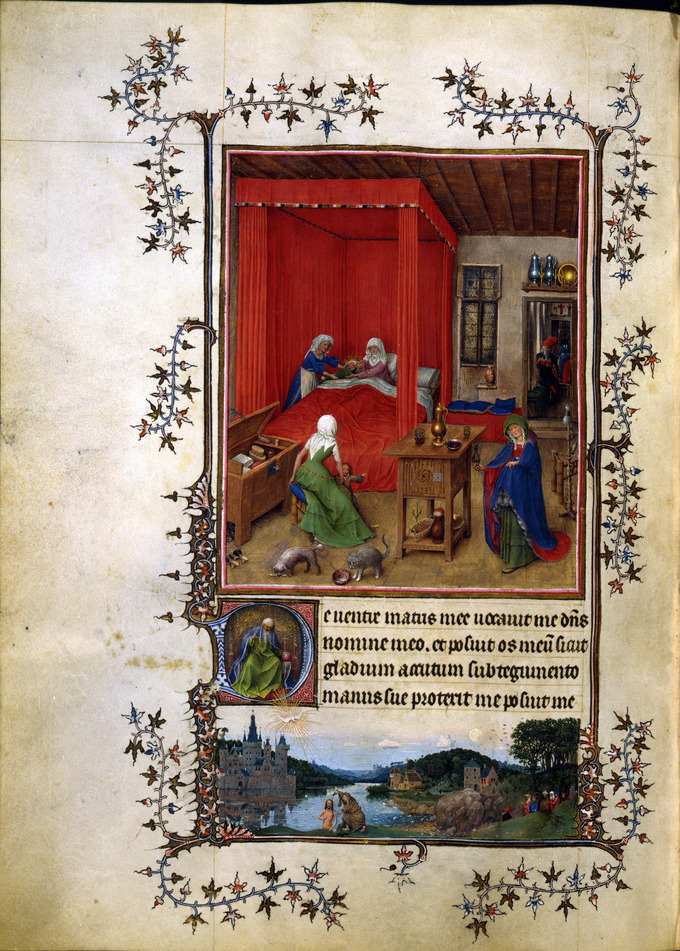

Page from the “Turin-Milan Hours,” anonymous artist known as Hand G.: The Birth of John the Baptist (top image) and the Baptism of Christ (bottom image) by “Hand G” Turin.

German Woodcuts

Printmaking by woodcut and engraving was already more developed in Germany and the Low Countries than anywhere else during the Renaissance.

Learning Objectives

Discuss German woodcuts of the 16th century

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Printmaking by woodcut and engraving was already more developed in Germany and the Low Countries than anywhere else, and the Germans took the lead in developing book illustrations.

- Martin Schongauer (c.1450–1491) is credited as the first artist to create an engraving.

- The most well-known artist of the German Renaissance is Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), who worked as a printmaker and engraver.

Key Terms

- woodcut: A print or a method of printmaking from an engraved block of wood.

- engraving: The practice of incising a design onto a hard, flat surface by cutting grooves into it.

- Albrecht Dürer: (1471–1528) A German painter, printmaker, mathematician, and theorist from Nuremberg, often regarded as the greatest artist of the Northern Renaissance.

Woodcuts and Engraving

Printmaking by woodcut and engraving was already more developed in Germany and the Low Countries than anywhere else during the Renaissance. The Germans took the lead in developing book illustrations. These were typically of a relatively low artistic standard, but were seen all over Europe, with the woodblocks often being lent to printers of editions in other cities or languages.

Martin Schongauer

Martin Schongauer (c. 1450–1491), from Southern Germany, is credited as the first artist to create an engraving; he was also a well-known painter. He is known for further developing the engraving methods by refining the cross-hatching technique to depict volume and shade. Another notable German printmaker is known as the “Housebook Master.” His prints were made in drypoint: he scratched his lines on the plate, leaving them much more shallow than they would be with an engraving.

The Fifth Foolish Virgin, engraving by Martin Schongauer, 1483.

Albrecht Dürer

The greatest artist of the German Renaissance, Albrecht Dürer, began his career as an apprentice to a leading workshop in Nuremberg, that of Michael Wolgemut, who had largely abandoned his painting to exploit the new medium . Dürer worked on the most extravagantly illustrated book of the period, The Nuremberg Chronicle, published by his godfather Anton Koberger, Europe’s largest printer-publisher at the time.

After completing his apprenticeship in 1490, Dürer traveled in Germany for four years and to Italy for a few months before establishing his own workshop in Nuremberg. He rapidly became famous all over Europe for his energetic and balanced woodcuts and engravings; he also continued his painting during this period.

Adam and Eve, engraving by Albrecht Dürer.

Block Books

The mass production of paper in 15th century Europe opened the door for the proliferation of printed books.

Learning Objectives

Describe the development of printed books in Northern Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Around 1450, small woodcut books called “block books,” or “xylographica,” came into prominence and began to be reproduced in large numbers. They are believed to have been less expensive than books printed with moveable type.

- Block books were short books consisting of up to 50 leaves. They were printed with woodcuts carved to include both text and imagery and were nearly always religious in nature.

- The most renowned block book is titled the Ars Moriendi, or The Art of Dying. This block book was from the Netherlands and was reprinted in several editions with different illustrations.

- The Biblia Pauperum involved visual depictions relating the Old Testament to the New Testament and often placed the illustrations in the center with very little additional text. Whenever writing did appear, it was in the vernacular language, as opposed to Latin.

- Unlike typical polychromatic prints, polychromatic block books were printed with a single block and subsequently hand painted.

Key Terms

- Pigment: Powdered coloring material that forms the basis of painting, drawing, and printing media.

- polychromatic: Multi-colored.

- monochromatic: Black and white, or using one color.

- woodcut: A method of relief printing in which the image is carved into the smooth side of a wooden block.

The increasing mass production of paper, coupled with the invention of the printing press in 15th century Europe, opened the doors for the proliferation of printed books. Woodcut printing on textiles had been practiced in Europe for some time when paper became more affordable and readily available. Around 1450, small woodcut books called “block books” or “xylographica” came into prominence and were reproduced in large numbers. Block books were short books consisting of up to 50 leaves block-printed with woodcuts carved to include both text and imagery. These books were aimed at a general audience and were often popular titles, nearly always religious in nature, and sometimes reprinted into multiple editions. Germany and Northern Europe were important centers for the spread and development of printed works during the 15th and 16th centuries.

It is widely believed that block books existed as a cheaper alternative to the movable-type printed book, which was in use but still very expensive. Research has uncovered over 40 titles, with a much smaller number ranking among the most popular. The most popular texts were reprinted many times, often using new woodcuts copying the earlier versions. Block books were typically printed as folios, with two pages printed on one full sheet of paper, which was then folded once for binding. Several such leaves were then inserted inside another to form a gathering of leaves, one or more of which would be sewn together to form the complete book. Some block books, called “chiro-xylographic,” were printed with only illustrations, and then the type was filled in by hand. Block books are considered incunabula (or “incunable”), a term referring to a book, pamphlet, or broadside printed before the year 1501 in Europe.

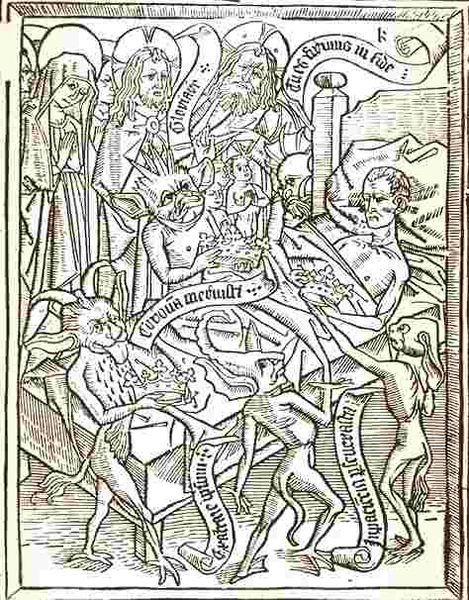

The most renowned block book is the Ars Moriendi, or The Art of Dying, from the Netherlands. It was reprinted in several editions with different illustrations. There was originally a “long version” and a later “short version” containing 11 woodcut pictures as instructive images that could be easily explained and memorized. It was written within the historical context of the effects of the macabre horrors of the Black Death 60 years earlier and consequent social upheavals of the 15th century. It was very popular, translated into most West European languages, and was the first in a Western literary tradition of guides to death and dying.

A Print from the Ars Moriendi: The Ars Moriendi is the most renowned block book.

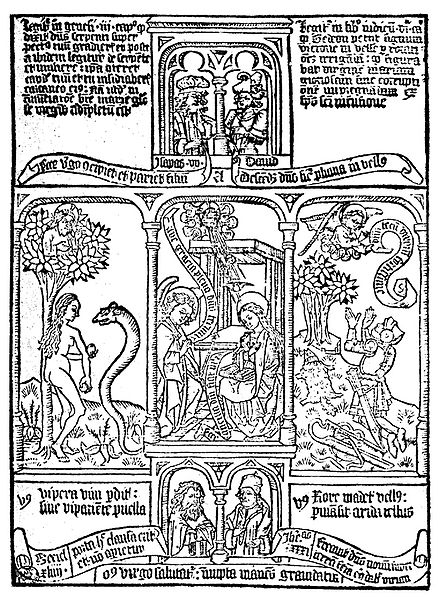

The Biblia Pauperum, or Pauper’s Bible, was also a popular series that had existed previously in the 14th century as illuminated manuscripts , hand-painted on vellum , before woodcuts took over. A Biblia Pauperum included visual depictions that related the Old Testament to the New Testament, often placing the illustrations in the center with very little additional text. When text did appear in the Biblia Pauperum, it was usually in the local vernacular language, rather than Latin. Each group of images is dedicated to one event from the Gospels, which is accompanied by two slightly smaller pictures of Old Testament events that prefigure the central one, according to belief of medieval theologians. Other notable Biblia paupera include the Gutenberg Bible of 1455, as well as the incunabula of 1486, printed and illustrated by Erhard Reuwich.

Woodblock Print from a Biblia Pauperum: Three episodes from the block book Biblia Pauperum illustrating typological correspondences between the Old and New Testaments: Eve and the serpent, the Annunciation, and Gideon’s miracle.

Polychromatic block books were produced in addition to the monochromatic ones. Whereas most polychromatic prints required a separate printing surface for each color used, polychromatic block books were colored by hand. Pigments ranged from plant materials, such as ochre (red and yellow), to more chemically-derived ones, such as cobalt (blue). Various insect species were also used for a variety of red values . Since block books were less expensive than traditional illuminated manuscripts, artists colored the images exclusively in paints and inks, as opposed to gilding.

Most of the earliest block books are believed to have been printed in the Netherlands, while the later ones are thought to be from Southern Germany. Specifically, Nuremberg, Ulm, Augsburg, and Schwaben were notable locations for the development of print media in the 15th and 16th centuries.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 14th-century painters - Les Tru00e8s Belles Heures de Notre Dame de Jean de Berry - WGA16014. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:14th-century_painters_-_Les_Tr%C3%A8s_Belles_Heures_de_Notre_Dame_de_Jean_de_Berry_-_WGA16014.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- illuminated manuscript. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/illuminated%20manuscript. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Early Netherlandish painting. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_Netherlandish_painting%23Illuminated_manuscripts. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Illuminated manuscript. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Illuminated_manuscript. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- scriptoria. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/scriptoria. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Simon Marmion. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Simon%20Marmion. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Philip the Good. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip%20the%20Good. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Albrecht_D%C3%BCrer%2C_Adam_and_Eve%2C_1504%2C_Engraving.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Albrecht_D%C3%BCrer. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Martin_Schongauer_-_The_Fifth_Foolish_Virgin_-_WGA21028.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_Schongauer. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- German art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/German_art%23Renaissance_painting_and_prints. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Matthias Grunewald. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Matthias%20Grunewald. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Albrecht Durer. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Albrecht%20Durer. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Martin Luther. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin%20Luther. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 359px-Apocalypse.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7751217. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Ars.moriendi.pride.a. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ars.moriendi.pride.a.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- BibliaPauperum. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:BibliaPauperum.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Block Book. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_book. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ars Moriendi. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ars_moriendi. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Biblia Pauperum. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Biblia_pauperum. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Illuminated Manuscript. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Illuminated_manuscript. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Old Master Print. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_master_print. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Woodcut. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/woodcut. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike