5.6: Reading- Photography

- Page ID

- 28307

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)EARLY DEVELOPMENT

The first attempts to capture an image were made from a camera obscura, used since the 16th century. The device consists of a box or small room with a small hole in one side that acts as a lens. Light from an external scene passes through the hole and strikes the opposite surface inside where it is reproduced upside-down, but with color and perspective preserved. The image is usually projected onto paper adhered to the opposite wall, and can then be traced to produce a highly accurate representation. Experiments in capturing images on film had been conducted in Europe since the late 18th century.

Using the camera obscura as a guide, early photographers found ways to chemically fix the projected images onto plates coated with light sensitive materials. Moreover, they installed glass lenses in their early cameras and experimented with different exposure times for their images. View from the Window at Le Gras is one of the oldest existing photographs, taken in 1826 by French inventor Joseph Niepce using a process he called heliograpy (“helio” meaning sun and “graph” meaning write). The exposure for the image took eight hours, resulting in the sun casting its light on both sides of the houses in the picture. Further developments resulted in apertures– thin circular devices that are calibrated to allow a certain amount of light onto the exposed film. Apertures allowed photographers better control over their exposure times.

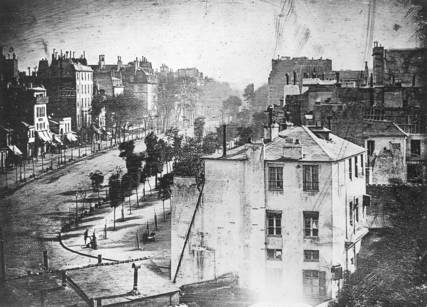

During the 1830’s Louis Daguerre, having worked with Niepce earlier, developed a more reliable process to capture images on film by using a polished copper plate treated with silver. He termed the images made by this process “Daguerreotypes”. They were sharper in focus and the exposure times were shorter. His photograph Boulevard du Temp from 1838 is taken from his studio window overlooking a busy Paris street. Still, with an exposure of ten minutes, none of the moving traffic or pedestrians (One exception. See if you can find it!) stayed still long enough to be recorded.

At the same time in England, William Henry Fox Talbot was experimenting with other photographic processes. He was creating photogenic drawings by simply placing objects (mostly botanical specimens) over light sensitive paper or plates, then exposing them to the sun. By 1844 he had invented the calotype; a photographic print made from a negative image. In contrast, Daguerreotypes were single, positive images that could not be reproduced. Talbot’s calotypes allowed for multiple prints from one negative, setting the standard for the new medium. Though Daguerre won the race to be first in releasing his photographic process, Talbot’s negative to positive process would eventually become the dominant process.

IMPACT ON OTHER MEDIA

The advent of photography caused a realignment in the use of other two-dimensional media. The photograph was now in direct competition with drawing, painting and printmaking. The camera turns its gaze on the human narrative that stands before it. The photograph gave (for the most part), a realistic and unedited view of our world. In its early beginning, photography was considered to offer a more “true” image of nature because it was created mechanically, not by the subjective hand of an artist. Its use as a tool for documentation was immediate, which gave the photo a scientific role to play. The sequential, instantaneous exposures by Eadweard Muybridge helped to understand human and animal movement, but also highlighted that photography could be used to expand human vision, imaging something that could not be seen with the naked eye. The relative immediacy and improved clarity of the photographic image quickly pitted the camera against painting in the genre of portraiture. Before photography, painted portraits were afforded only to the wealthy and most prominent members of society. They became symbols of social class distinctions. Now portraits became available to individuals and families from all social levels.

Photography as an Art

It wasn’t long before photographers recognized the aesthetic value of a photograph. As a new medium, photography began the march towards being considered a high form of art. Alfred Stieglitz understood this potential, and as a photographer, editor and gallery owner, was a major force in promoting photography as an art form. He led in forming the Photo Secession in 1902, a group of photographers who were interested in defining the photograph as an art form in itself, not just by the subject matter in front of the lens. Subject matter became a vehicle for an emphasis on composition, lighting and textural effects. His own photographs reflect a range of themes. The Terminal (1892) is an example of “straight photography”: images from the everyday taken with smaller cameras and little manipulation. In The Terminal Stieglitz captures a moment of bustling city street life on a cold winter day. The whole cold, gritty scene is softened by steam rising off the horses and the snow provides highlights. But the photo holds more than formal aesthetic value. The jumble of buildings, machines, humans, animals and weather conditions provides a glimpse into American urban culture straddling two centuries. Within ten years from the time this photo was taken horses will be replaced by automobiles and subway stations will transform a large city’s movement into the twentieth century.

Photojournalism and photography’s many subject placements

Photography is a medium that has multiple subject placements. It is used as an art medium, in journalism, in advertising, the fashion industry, and we use it to personally document our lives. It is one, if not the most, pervasive form of documentation in the world. These multiple subject placements make it a complex phenomena to analyze.

The news industry was fundamentally changed with the invention of the photograph. Although pictures were taken of newsworthy stories as early as the 1850’s, the photograph needed to be translated into an engraving before being printed in a newspaper. It wasn’t until the turn of the nineteenth century that newspaper presses could copy original photographs. Photos from around the world showed up on front pages of newspapers defining and illustrating stories, and the world became smaller as this early mass medium gave people access to up to date information…with pictures!

Photojournalism is a particular form of journalism that creates images in order to tell a news story and is defined by these three elements:

- Timeliness — the images have meaning in the context of a recently published record of events.

- Objectivity — the situation implied by the images is a fair and accurate representation of the events they depict in both content and tone.

- Narrative — the images combine with other news elements to make facts relatable to the viewer or reader on a cultural level.

- As visual information, news images help in shaping our perception of reality and the context surrounding them.

Photographs taken by Mathew Brady and Timothy O’Sullivan during the American Civil War (below) gave sobering witness to the carnage it produced. Images of soldiers killed in the field help people realize the human toll of war and desensitize their ideas of battle as being particularly heroic.

Photojournalism’s “Golden Age” took place between 1930 and 1950, coinciding with advances in the mediums of radio and television.

Dorothea Lange was employed by the federal government’s Farm Security Administration to document the plight of migrant workers and families dislocated by the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression in America during the 1930’s. Migrant Mother, Florence Owens Thompson, Nipomo Valley, California is an iconic image of its hardships and the human resolve to survive. Like O’Sullivan’s civil war photos, Lange’s picture puts a face on human tragedy. Photographs like this helped win continued support for president Franklin Roosevelt’s social aid programs.

Modern Developments

Edwin Land invented the instant camera, capable of taking and developing a photograph, in 1947, followed by the popular SX-70 instant camera in 1972. The SX-70 produced a 3-inch-square-format positive image that developed in front of your eyes. The beauty of instant development for the artist was that during the two or three minutes it took for the image to appear, the film emulsion stayed malleable and able to manipulate. The artist Lucas Samaras used this technique of manipulation to produce some of the most imaginative and visually perplexing images in a series he termed photo-transformations. Using himself as subject, Samaras explores ideas of self-identity, emotional states and the altered reality he creates on film.

Digital cameras appeared on the market in the mid 1980s. They allow the capture and storage of images through electronic means (the charge-coupled device) instead of photographic film. This new medium created big advantages over the film camera: the digital camera produces an image instantly, stores many images on a memory card in the camera, and the images can be downloaded to a computer, where they can be further manipulated by editing software and sent anywhere through cyberspace. This eliminated the time and cost involved in film development and created another revolution in the way we access visual information.

Digital images start to replace those made with film while still adhering to traditional ideas of design and composition. Bingo Time by photographer Jere DeWaters (below) uses a digital camera to capture a visually arresting scene within ordinary surroundings. He uses a rational approach to create a geometric order within the format, with contrasting diagonals set up between sloping pickets and ramps, with an implied angle leading from the tire on the lower left to the white window frame in the center and culminating at the clock on the upper right. And even though the sign yells out to us for attention, the black rectangle in the center is what gets it.

In addition, digital cameras and editing software let artists explore the notion of staged reality: not just recording what they see but creating a new visual reality for the viewer. Sandy Skogland creates and photographs elaborate tableaus inhabited by animals and humans, many times in cornered, theatrical spaces. In a series of images titled True Fiction Two she uses the digital process – and the irony in the title to build fantastically colored, dream like images of decidedly mundane places. By straddling both installation and digital imaging, Skoglund blurs the line between the real and the imagined in art.

The photographs of Jeff Wall are similar in content—a blend of the staged and the real, but presented in a straightforward style the artist terms “near documentary.”