5.3: Reading- Drawing

- Page ID

- 28303

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction

Drawing is the simplest and most efficient way to communicate visual ideas, and for centuries charcoal, chalk, graphite and paper have been adequate enough tools to launch some of the most profound images in art. Leonardo da Vinci’s The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist wraps all four figures together in what is essentially an extended family portrait. Da Vinci draws the figures in a spectacularly realistic style, one that emphasizes individual identities and surrounds the figures in a grand, unfinished landscape. He animates the scene with the Christ child pulling himself forward, trying to release himself from Mary’s grasp to get closer to a young John the Baptist on the right, who himself is turning toward the Christ child with a look of curious interest in his younger cousin.

The traditional role of drawing was to make sketches for larger compositions to be manifest as paintings, sculpture or even architecture. Because of its relative immediacy, this function for drawing continues today. A preliminary sketch by the contemporary architect Frank Gehry captures the complex organic forms of the buildings he designs.

Types of Drawing Media

Dry Media includes charcoal, graphite, chalks and pastels. Each of these mediums gives the artist a wide range of mark making capabilities and effects, from thin lines to large areas of color and tone. The artist can manipulate a drawing to achieve desired effects in many ways, including exerting different pressures on the medium against the drawing’s surface, or by erasure, blotting or rubbing.

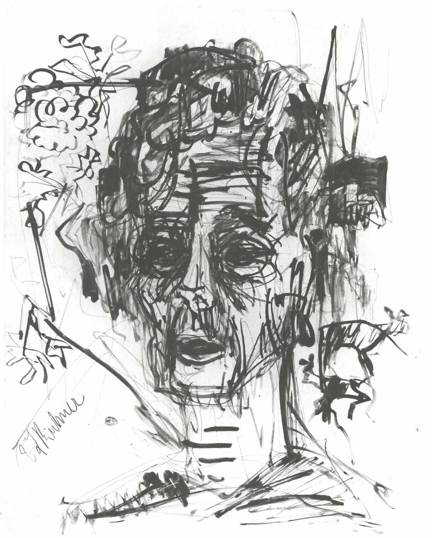

This process of drawing can instantly transfer the sense of character to an image. From energetic to subtle, these qualities are apparent in the simplest works: the immediate and unalloyed spirit of the artist’s idea. You can see this in the self-portraits of two German artists; Kathe Kollwitz and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. Wounded during the first world war, his Self-Portrait Under the Influence of Morphine from about 1916 presents us with a nightmarish vision of himself wrapped in the fog of opiate drugs. His hollow eyes and the graphic dysfunction of his marks attest to the power of his drawing.

Graphite media includes pencils, powder or compressed sticks. Each one creates a range of values depending on the hardness or softness inherent in the material. Hard graphite tones range from light to dark gray, while softer graphite allows a range from light gray to nearly black. French sculptor Gaston Lachaise’s Standing Nude with Drapery is a pencil drawing that fixes the energy and sense of movement of the figure to the paper in just a few strokes. And Steven Talasnik’s contemporary large-scale drawings in graphite, with their swirling, organic forms and architectural structures are testament to the power of pencil (and eraser) on paper.

Charcoal, perhaps the oldest form of drawing media, is made by simply charring wooden sticks or small branches, called vine charcoal, but is also available in a mechanically compressed form. Vine charcoal comes in three densities: soft, medium and hard, each one handling a little different than the other. Soft charcoals give a more velvety feel to a drawing. The artist doesn’t have to apply as much pressure to the stick in order to get a solid mark. Hard vine charcoal offers more control but generally doesn’t give the darkest tones. Compressed charcoals give deeper blacks than vine charcoal, but are more difficult to manipulate once they are applied to paper.

Charcoal drawings can range in value from light grays to rich, velvety blacks. A charcoal drawing by American artist Georgia O’Keeffe is a good example.

Pastels are essentially colored chalks usually compressed into stick form for better handling. They are characterized by soft, subtle changes in tone or color. Pastel pigments allow for a resonant quality that is more difficult to obtain with graphite or charcoal. Picasso’s Portrait of the Artist’s Mother from 1896 emphasizes these qualities.

More recent developments in dry media are oil pastels, pigment mixed with an organic oil binder that deliver a heavier mark and lend themselves to more graphic and vibrant results. The drawings of Beverly Buchanan reflect this. Her work celebrates rural life of the south centered in the forms of old houses and shacks. The buildings stir memories and provide a sense of place, and are usually surrounded by people, flowers and bright landscapes. She also creates sculptures of the shacks, giving them an identity beyond their physical presence.

Wet Media

Ink: Wet drawing media traditionally refers to ink but really includes any substance that can be put into solution and applied to a drawing’s surface. Because wet media is manipulated much like paint – through thinning and the use of a brush – it blurs the line between drawing and painting. Ink can be applied with a stick for linear effects and by brush to cover large areas with tone. It can also be diluted with water to create values of gray. The Return of the Prodigal Son by Rembrandt shows an expressive use of brown ink in both the line qualities and the larger brushed areas that create the illusion of light and shade.

Felt tip pens are considered a form of wet media. The ink is saturated into felt strips inside the pen then released onto the paper or other support through the tip. The ink quickly dries, leaving a permanent mark. The colored marker drawings of Donnabelle Casis have a flowing, organic character to them. The abstract quality of the subject matter infers body parts and viscera.

Other liquids can be added to drawing media to enhance effects – or create new ones. Artist Jim Dine has splashed soda onto charcoal drawings to make the surface bubble with effervescence. The result is a visual texture unlike anything he could create with charcoal alone, although his work is known for its strong manipulation. Dine’s drawings often use both dry and liquid media. His subject matter includes animals, plants, figures and tools, many times crowded together in dense, darkly romantic images.

Traditional Chinese painting uses water-based inks and pigments. In fact, it is one of the oldest continuous artistic traditions in the world. Painted on supports of paper or silk, the subject matter includes landscapes, animals, figures and calligraphy, an art form that uses letters and script in fluid, lyrical gestures.

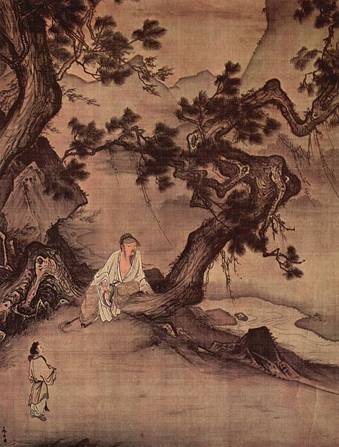

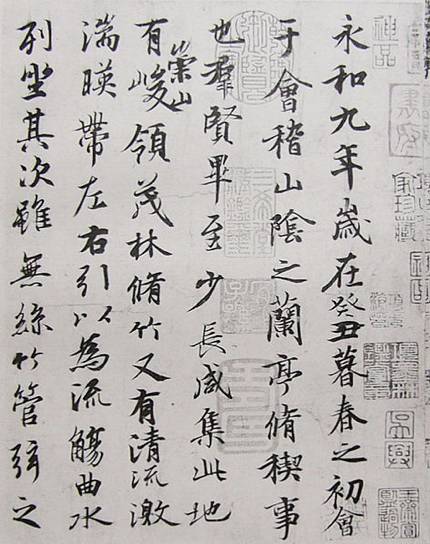

Two examples of traditional Chinese painting are seen below. The first, a wall scroll painted by Ma Lin in 1246, demonstrates how adept the artist is in using ink in an expressive form to denote figures, robes and landscape elements, especially the strong, gnarled forms of the pine trees. There is sensitivity and boldness in the work. The second example is the opening detail of a copy of “Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion” made before the thirteenth century. Using ink and brush, the artist makes language into art through the sure, gestural strokes and marks of the characters.

Drawing is a foundation for other two and three-dimensional works of art, even being incorporated with digital media that expands the idea of its formal expression. The art of Matthew Ritchie starts with small abstract drawings. He digitally scans and projects them to large scales, taking up entire walls. Ritchie also uses the scans to produce large, thin three-dimensional templates to create sculptures out of the original drawings.