16.4: Design and Architecture in the 1930s- Corporate Patronage and Individual Genius

- Page ID

- 232362

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)"Style is a manifestation of an attitude toward life. It serves to chronicle a period as effectively as written history."16

As with other subjects examined in this chapter, American design in the interwar years reached out to a mass public. Along with the Democratic Front and other populist movements, the design industry rendered modernism into accessible form. But unlike the politicized public art of the 1930s, design was firmly entrenched within a consumer market that addressed well-being from an entirely different direction. Design shared with Social Realism and documentary the arts of persuasion, but it did so through everyday objects that appealed to consumer fantasies and anxieties.

Design involves a self-conscious approach to the creation of objects that form the environments in which we live: furniture, appliances, lighting fixtures, rugs, and textiles, as well as a range of new consumer and industrial products, such as cars and trains. In expanding to reach a mass public, design developed from the realm of customized luxury items-labor-intensive and made from costly materials into broadly marketed, affordable consumer goods. Sharing in the democratizing impulse of other forms of cultural expression, design history nonetheless offers a different perspective on the years of crisis. Designers responded to the public's desires for psychological and historical reassurance. However, rather than looking to the past-to narratives that located the present within a perspective of history- designers pursued several strategies to promote consumer confidence about the future: by appealing to a reassuring professional expertise, by streamlining forms to create comforting environments, and by making an engineered future appear exciting, desirable, and inevitable.

Design was distinct from manufacturing, and engaged an unprecedented range of social institutions, from corporate business and industry to museums, retailers, advertisers, and consumers. All of these played their part in the look, promotion, and circulation of designed objects which reshaped the everyday world of millions of Americans.

Mass-Marketing the Modern: Industrial Design

By the early 1930s, American designers were actively pursuing new models of how to marry mass production and industrial materials to good design. "The machine is a communist!" proclaimed the cultural critic Lewis Mumford (1895- 1990) in 1930, recognizing its potential to level class and social distinctions by making good industrial design available to all. In pursuit of better models, design between the wars drew lessons from a variety of European modernist sources, from the German Bauhaus ( established in Weimar Germany in 1919 with precisely those aims) to Scandinavian modern. Supported by an odd alliance of artists, manufacturers, museums, and department stores- Lord and Taylor, Macy's, and Saks among them-the "design in industry" movement promoted affordable domestic consumer goods. Many of the main contributors to American design in the years between the wars were emigres: Paul Frankl (1886-1958) and Joseph Urban (1872-1933) from Vienna; Kem Weber (1889-1963) from Germany; Eliel Saarinen (1873-1950) from Finland, along with his son Eero (1910-61), who would go on to become a leading postwar designer and architect; Raymond Loewy (1893-1987) from France, and many others. These men were eventually joined by a number of talented Americans, many of whom studied or traveled in Europe during these seminal years. Exploiting new materials such as plastics, Bakelite, Formica, aluminum, stainless steel, and chrome, these designers combined the lessons of purity, simplicity, and elimination of ornament learned from European modernism, with manufacturers' and marketers' concepts of practicality and desirability.

Industrial design, along with advertising, commercial photography, and graphics, took modernism and domesticated and popularized it. Modernist concerns with pure form were now routinely applied, not only to the fine arts, but to everything from refrigerators to bridges. Designers such as Norman Bel Geddes (1893- 1958) won celebrity status, while artists such as Charles Sheeler, Charles Burchfield (1893- 1967), and John Storrs (1885- 1956) designed textiles, rugs, and wallpaper. The painter and printmaker Louis Lozowick (1892-1973)-who did much to promote Russian Constructivism in the United States- and the sculptor Alexander Archipenko (1887-1964) (see fig. 13.26) both designed store window displays, linking avant-garde styles to high fashion.

THE STREAMLINED STYLE. The "design in industry" movement had its origins in the late nineteenth century, taking root in England, and thereafter in Germany. Brought over to the United States by emigre designers between the wars, it encountered a receptive environment. American businesses, advertisers, and retailers seized on modern styling as a highly effective marketing tool. Responding to the consumer's desire to be "up-to-date," designers and their corporate sponsors devised a style in the 1930s known as "Streamlined" that would supplant Art Deco. The crisis of the Depression brought a longing for psychological reassurance and a reaction against the edgy, nervous dynamism of Art Deco. Art Deco corresponded to what Richard Wilson has termed the "machine-as-parts" aesthetic in which individual design elements are incorporated in a composition featuring abrupt transitions and sudden changes of scale. In Streamlined design, visual continuity replaces fractured planes, and sleek smooth contours replace jagged silhouettes. Horizontal extension, suggesting continuity across space and time, replaces vertical aspiration as the new axis of the modern. The Streamlined style extended its reach from teapots, lamps, automobiles, and trains to sculpture and buildings in an integrated interior design.

First articulated as a design principle by the European modernist Le Corbusier, the Streamlined style came to be widely applied by American industry. Streamlining began through the principles of aerodynamic flight (the elimination of "drag"). Speed had become the primary metaphor driving the search for a modern form. Ultimately it drove the redesign of everyday life, consistent with the modern ideals of efficiency, hygiene, rationality, and the elimination of waste. In practice, streamlining had rather little to do with functional efficiency, but it had a great deal to do with cushioning the consumer's encounter with technology.

Perhaps the most intimate of these encounters occurred in the home, where objects, mass-produced and standardized, brought a tactile and sensory immediacy to the vague promises of a better life. In the home, objects generally stayed in place rather than flying through the air, so the principle of minimizing aerodynamic drag made no sense. Yet industrial designers such as Raymond Loewy routinely encased stationary objects like pencil sharpeners (fig. 16.25) and meat slicers in sleek streamlined forms. Any claims to functional necessity dissolve before the sheer absurdity of a streamlined tricycle. The "function" of streamlining, in short, was emotional reassurance; the complicated, unwieldy interiors of gadgets and appliances were shrouded in smooth surfaces that insulated the user from the shock and rough edges of modern technology. From science fiction to urban visionary planning, a "brave new world" promised to free audiences from the discomforts of the past. Streamlining symbolized a speedy, smooth voyage into the future. As Lewis Mumford aptly put it in 1934, "simplification of the externals of the mechanical world is almost a prerequisite for dealing with its internal complications."17

The genius behind this new modern vernacular was the industrial designer, who made his first appearance in the 1930s (fig. 16.26). Like the technological wizards of science (the man behind the curtain, in The Wizard of Oz) and the dream factories of the Hollywood studio system, product designers disguised their methods, appealing to the psychological needs of consumers. Streamlining was applied not only to cars, trains, and appliances, but to bodies and labor processes as well (see Box, p. 519). Yet ironically, the corporate obsession with efficiency created tremendous waste: garbage dumps of fully functional appliances, rendered stylistically obsolete; thousands of deaths each year on streamlined highways and parkways. The cult of efficiency, applied to urban spaces, produced a network of superhighways that sliced through neighborhoods, dislocating urban populations, leaving inner cities isolated from residential areas, and creating an environmentally devastating dependence on the automobile.

The Machine Art Show at the Modern

The Museum of Modern Art in New York City took a different approach in defining an industrial aesthetic. In 1934, the Modern, since its establishment in 1929 the leading institution promoting modernism in the arts, sponsored an exhibition of machine parts-including a variety of industrially produced springs, coils, boat and airplane propellers, and ball bearings-followed by household appliances, hospital supplies, and scientific instruments (fig. 16.27). These springs, coils, and propellers were not found objects in the sense of Duchamp's porcelain urinal, with its frontal assault on the notion of art as a privileged realm. The intention of Alfred Barr, director of the Modern, was not, as with Duchamp, to challenge the aesthetic gaze but to widen it to include machines, machine parts, and machine made products. For Barr, these represented the purity of platonic forms, of "straight lines and circles," machines created by machines in an unintended play on the self-generating power of technology that was the subject of New York dada's "machine born without a mother." But unlike dada, the exhibition at the Modern was full of high-minded devotion to the formal properties of machines. Audiences were asked to see these industrial objects as art.18

Barr and his curator, the young architect Philip Johnson, repudiated the historicism of "revival" styles, along with the contemporary Art Deco and the Streamlined style which the Museum of Modern Art felt appealed to irrational desires and lacked the rigor of "machine art." But in the trough of the Depression, the machine aesthetic was contested by industrial workers who wished to assert their role in the process of production. Machines were not born of other machines but of the men who made them; this was the insistent message of Lewis Hine's Men at Work and Empire State series, a rebuke directed at the aestheticized machine.

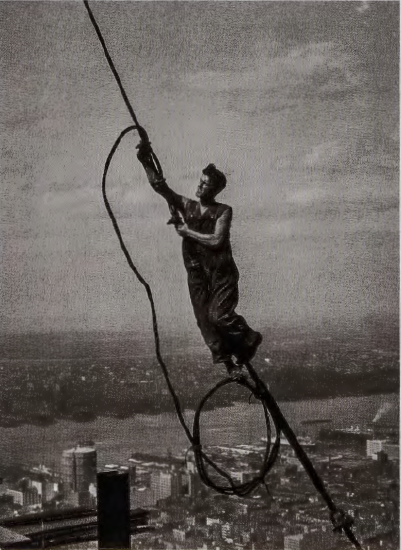

LEWIS HINE'S MEN AT WORK. "Cities do not build themselves, machines cannot make machines, unless [at the] back of them all are the brains and toil of men. We call this the Machine Age. But the more machines we use the more do we need real men to make and direct them." So said Lewis Hine (1874-1940).19 Throughout much of American history, "manliness" and "independence" were closely related terms. The godlike power of the muscular male body was a crucial element of Depression-era iconography, from poster art to public murals. Such images reinstated faith in human agency at a time when technology offered an uncertain promise of economic and social recovery. Lewis Hine's photographs of men at work, done toward the end of a long career that began in the early 1900s, leave no doubt about who is in command. The body of the worker in his later photography comes to symbolize the integrity of the republic itself. Hine's men at work, making the machines, building the skyscrapers, balancing gracefully if precariously at the edge of the horizon, represented productive labor at a time of massive unemployment. Icarus Atop Empire State Building (fig. 16.28) was part of a series Hine did on the construction of what was then the tallest building in the world. This collective portrait of the men behind the building required the aging photographer to be hoisted to the top of the construction site, a hundred floors above the city, where his own work replicated the heroism of his subjects. Icarus- referring to the Greek myth of the heedless youth who flies too close to the sun suggests both the aspiration and the risk associated with the ambition of the modern skyscraper city. In Hine's photographs, these are expressed by the reckless grace of the worker. No longer identifying himself as a documentary photographer, Hine described his work as "interpretive."20 Drawing upon traditional American values, he projected a heroic image of labor-a utopian vision of the body opposed to the disembodied aesthetics of the Machine Art show.

Corporate Utopias: The World's Fairs of the 1930s

Utopian projections of a streamlined future were accompanied by vivid anxieties about machines. Mechanization furnished the key to the future, but it also fueled fears of a soulless world of robotic men driven by motorized impulses. In the 1930s such contradictory attitudes reached new levels, as Americans invested in a corporate-sponsored vision of the future, while simultaneously seeking refuge in nostalgic visions of an older agrarian republic.

The world's fairs of 1933 (Chicago) and 1939 (New York) were awesome, Oz-like spectacles-glistening stage sets, complete with colored floodlights that furnished magical night-time illumination, and elaborate displays of consumer goods and services promising a new version of "the American way of life" grounded in mass production. Visitors could temporarily ignore the threat of fascism abroad and the painful and halting recovery from the Depression at home. Yet the corporate sponsors of 1939 grounded their spectacle of the future in the reassuring imagery of the past. Presiding over the fair was a monumental statue of George Washington, the nation's father figure, reminding visitors of their history in the midst of accelerating change. Fairgoers were urged to embrace innovation in the context of tradition. The glittering new appliances featured in corporate pavilions allowed Americans to cash in on the benefits of science allied to industry. Such modernistic appliances could be found in Colonial Revival homes like that of George F. Babbitt, the frumpy leading man of Babbitt, Sinclair Lewis's novel of 1922. Lewis put his finger on the split personality of middleclass Americans, their days regulated by sleek gadgets like Babbitt's alarm clock, "the best of nationally advertised and quantitatively produced .. . with all modern attachments," their nights haunted by dreams of escape.

Consistent with its largely corporate sponsorship, the 1939 World's Fair sported a logo that was used on everything from sheet music to advertisements: the Trylon and Perisphere at the heart of the fair (fig. 16.29). Resembling forms celebrated at the Machine Age exhibition, they modified the revolutionary aesthetics of Russian Constructivism, which had migrated to the United States from Europe in the 1920s, into an American vernacular. The Trylon suggested rocket-like energies that could carry the nation from the depths of the Depression to a soaring new space age. The Perisphere enclosed them in a womblike space where they experienced a miniaturized and controlled encounter with the future. In "Democracity" superhighways directed frictionless flow through space, and high-rise buildings preserved the countryside by eliminating sprawl. Dynamic and protective, the complementary forms of Trylon and Perisphere reproduced the cultural spheres of male and female, public and private. They implied an ideal world where the energies of thrust and progress were balanced by stasis and containment.

Frank Lloyd Wright in the 1930s

Product design was closely adjusted to the demands of consumption. Minor stylistic changes-or redesign-signaled that a product differed from last year's model, and was therefore more "up-to-date." Stylistic obsolescence, first identified as a marketing strategy in the 1930s, assured that no form was permanent or absolute, but was destined to change according to the imperatives of consumer "taste."

This fluctuating realm of taste-an unstable amalgam of advertising, consumer insecurity, and consumer desire-was antithetical to the ambitions of modernist architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959), whose quest for elemental form went hand-in-hand with an uncompromising personal vision. Wright's career bridged progressive forces in American architecture and organicist, nature-based design philosophies deeply tied to the previous century. His buildings balanced structural innovation with powerfully expressive forms in a manner that spoke to his clients' desire for a modernity with roots.

Over his later career, Wright designed for virtually every building type, including skyscrapers and government centers. He devised inventive new solutions for each client and commission, working through a set of principles to which he was firmly committed until his death in 1959, grounded in an endlessly varied geometry of forms which carried specific symbolic meanings: circles (infinity), triangles (stability), squares (integrity), spirals (organic process).21 His preference for elemental forms guided his encounter with a number of new architectural influences in the years between the wars. It also shaped a practice distinct from the main idioms of the time: Bauhaus-inspired functionalism, Art Deco and Streamlined, and historicist. Each of these styles spoke to specific audiences; Wright, by contrast, aspired to a "democratic" architecture freed from earlier models, and universal in its appeal. His version of democracy, however, turned from shared collective symbols toward the leadership of visionary individuals, whose power to point the way toward the future would be taken on faith by those wise enough to listen.

What Anthony Alofsin has termed the "primitivist" phase of Wright's career led him to a range of non-Western influences. Wright's philosophy of design drew on ancient forms found in what were then considered "primitive" or folk cultures-a return to first principles that motivated other phases of modernism between the wars. This contact with non-Western societies had contributed to the renewal of nineteenth-century architecture. Wright's assimilation of global traditions reinforced a belief that to be an American was to have the resources of the world's cultures at one's disposal. Like his mentor Louis Sullivan, Wright assumed the position of a prophet whose role would be to educate his people in the virtues of a living architecture. Toward this end, he carried on far-ranging dialogues with a variety of building traditions from around the world, expressing admiration for Maya and African, as well as Chinese and Japanese building traditions. These fueled his endlessly fertile imagination.

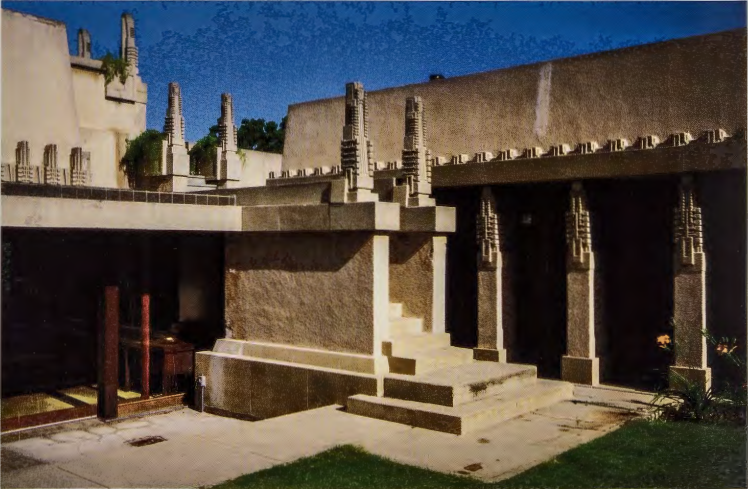

Already by the late 1910s, Wright was exploring the heavy massing, inward-turning quality, and battered walls of Central American and Southwest adobe architecture. In his design for an heiress and arts patron, Aline Barnsdall, in Los Angeles (1916-21), known as the "Hollyhock House" (fig. 16.30), he drew upon Maya architectural forms for the terraced walkways that circulate on the roofs of the house itself. The interior courtyards of European villas and Southwest haciendas were another inspiration. The house took its name from the mold-cast ornamentation of stylized flowers that forms a unifying motif throughout. Suggesting monumental permanence in a city known for its mobility, the Hollyhock House is constructed of stucco-on-lathe, though resembling the concrete that Wright would use in other Los Angeles houses designed in the 1920s. As William Curtis has pointed out,22 the theatrical siting, massive forms, and decorative wall textures were well suited for a house originally conceived as the center of an extended arts complex, echoing as well the extravagant stage sets of Hollywood in the 1920s.

Despite his claims to being unique and American, Wright was fully international, a fact evident in the people who worked for him. His office included apprentice architects from Japan, Puerto Rico, Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Switzerland; he pursued important exchanges and friendships with German architects including Erich Mendelsohn (1887- 1953), a modernist architect and writer who promoted Wright's reputation in that country, as well as with Dutch and English practitioners. Wright's home and office, Taliesin, in Spring Green, Wisconsin, became a site of pilgrimage for many young European architects. Wright more than gave back what he learned from other traditions: his buildings and proselytizing writings would help architects from Japan, Mexico, and elsewhere rediscover their own architectural heritage.

Natural architecture was among the ideas Wright most tirelessly advocated. By "natural architecture," however, he did not mean that his buildings should blend into nature. The concept of an organic architecture meant, above all, a form of design responsive to the specific needs of the client and the conditions of the site itself. His Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, for instance, was set on floating foundations placed on movable concrete sections that would not break up under severe stress. As a result, th«:t Imperial was one of the few buildings to withstand a devastating earthquake shortly after its completion in 1922. Yet his notion of organic architecture could also be at variance with natural facts such as gravity and rainfall; his beloved cantilevers sag; his long low roofs leak.

FALLINGWATER. Along with Monticello and Mount Vernon, Fallingwater (1934-7 Bear Run, Pennsylvania) is one of the most famous houses in America, and it catapulted Wright, by this time almost seventy years old, back into the limelight after a long period of public indifference toward his work. The most widely circulated view of the house is from below, looking up at a powerful composition of intersecting planes, formed by the cantilevers for which the house is famous (fig. 16.31). Vertical and horizontal planes are further distinguished by differences in material, from the smooth warm colored concrete with its softened edges, to the stratified_ limestone chimney and central core, which anchor the dynamic reach of the cantilevers. At the heart of this complex interplay is a rectangular living/ dining room around which the various subsidiary spaces are arranged.

This central space (fig. 16.32) is low-ceilinged, directing one's sight outward through the strip of windows toward the woods beyond. Unlike the inward-turning Prairie homes of Wright's early career, with their suburban locations, Fallingwater lets light and nature in. The cantilevers, projecting unsupported into space, create a series of outdoor extensions of the living room and the master bedroom on the second floor. The four elements of nature enliven the living room: fire (in the central hearth), water (in the perpetual sound of the stream and falls over which the house is built), air (in the play of light), and earth (in the great boulder that rises up from the sublevels of the house to break through the surface of the floor). Nature is not merely seen, but heard and touched, evoked and experienced.

According to later accounts, Fallingwater was conceived in one day. Commissioned as a weekend retreat by Edgar Kaufmann Sr., the owner of a successful department store business in nearby Pittsburgh, Fallingwater married technology to nature in a classic solution both brilliantly inventive and grounded in the familiar. With its assertive geometries and modern materials and construction methods, Fallingwater shared in the machine-age aesthetics of the decades between the wars. Anchored to the bedrock, its cantilevers project over Bear Creek to a waterfall directly beneath the house. Engineered controversially at the time, these cantilevers would eventually require complete restructuring and restabilization. Throughout his career, Wright had embraced methods and materials still new to architecture, sometimes pushing them past their performance limits.

Wright's particular concerns as an architect working within an American tradition become clearer in relation to the work of his famous contemporary, the Swiss architect Le Corbusier, whose Villa Savoye of 1928-30 (fig. 16.33) parallels Fallingwater as a landmark of modernist domestic design. In these years between the two world wars, both Le Corbusier and Wright were preoccupied with "type-forms," the purified expression of basic forms found in nature. Both architects drew on deep study of the past. Le Corbusier' s conception of the past was framed by the classical tradition, while Wright drew upon older American ideals concerning the role of nature in shaping culture and generating the abstract principles of design. Edgar Kaufmann Jr., who lived in the house for many years, observed that Wright proceeded "from principle, not from precedent."23 If mobility, circulation, and flow are central features of Villa Savoye, Fallingwater offers instead a primordial quality of shelter, permanence, and stability.

Wright framed his organic architecture in opposition to the European "International Style," as embodied in the Villa Savoye. He denounced its boxlike forms and flat cut-out quality, in favor of designs that were "elemental ... complementary to [their] natural environment."24 Wright insisted upon the tactile and the sensuous, in contrast to what he felt was the sterility of the International Style.