16.3: The Varieties of Photographic Documentary

- Page ID

- 232361

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The economic crisis of the 1930s brought a new national mood and set of social concerns into photography, as it did into other art forms. Many photographers turned away from the emphasis on formal values that had dominated the first generation of modernists around Stieglitz, embracing instead politically and socially engaged forms and subjects. Photographic form and meaning became as actively debated as other areas of visual practice in the politicized climate of the Depression era.

The "File": The Farm Security Administration and "the Camera with a Purpose"

In the 1930s, the documentary mode extended from journalism to newsreels to mass circulation magazines, and from still photography to film, as well as spanning a wide range of photographers and practices. Part of the New Deal, the Farm Security Administration, or FSA, as it was known, sponsored much of the documentary work in these years. Known as the Resettlement Administration from 1935 to 1937, the FSA addressed the problems of drought, soil exhaustion, and flooding that had devastated the nation's farming communities. The photographic section of the FSA was part of its publicity department, and was dedicated to creating a visual archive (the "File") numbering some 77,000 prints (from a larger archive of 145,000 negatives) and documenting the nation in these years- its coal miners, small towns, cities, family farms, breadlines and destitution, popular culture, and everyday landscapes. Directed from Washington by Roy Stryker, the File employed a corps of sixteen photographers between its founding, in 1935, and 1943, when it was incorporated into the Office of War Information to serve pressing wartime needs.

One purpose of the File was to win public approval for federal intervention on behalf of the nation's farmers. With its images of lives ravaged by natural conditions produced by decades of human and social mismanagement, the FSA documentary work argued the need for public assistance to an audience raised to believe that responsibility rested with the individual. As head of the photographic project, Stryker gave his staff photographers "shooting scripts" that encouraged full coverage-work, home, and community- of their complex subjects. In the field, the FSA photographers employed a variety of techniques- composition, framing, lighting, camera angle, point of view- to shape the messages viewers took away from their images.

The "transparency" of photography, the appearance that it captures the world directly, without the intervention of subjective intentions, seems to suggest a distinctive "truth value" of the photograph as documentary. However, documentary is a genre with its own conventions of representation-a style mediated by certain visual cues or codes that paradoxically signify that the image is unmediated, a transcription of the real world. In truth, creative decisions, and the desire to convey specific content, begin the moment a photographer picks up a camera. Images from the File were available to the public, the press, and the publishing world, and still are today: for a nominal fee of $10.00 anyone can order a print from any negative in the File, which is now digitized and available through the Library of Congress, which houses it. When captioned, positioned within a larger sequence of images, or located within a broader narrative, the documentary image could be made to support widely varying points of view, thus belying its claims to objective "truth." Documentary was, in the words of one practitioner, "a camera with a purpose."

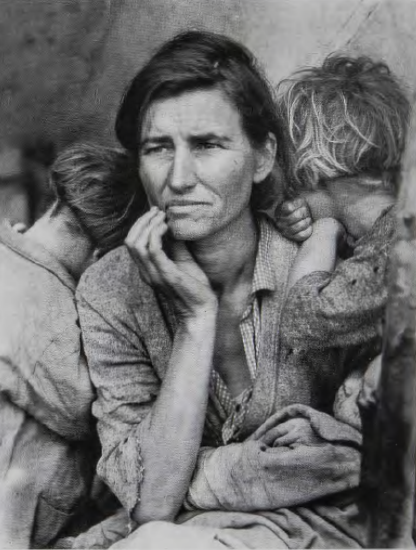

DOROTHEA LANGE. Lange's photograph Migrant Mother (fig. 16.21) drew on the fine arts and on a familiar language of motherhood to document the plight of migrant farmworkers in California's Central Valley. Lange took a series of shots of the thirty-two-year-old Florence Thompson and her children at a makeshift roadside camp, varying the distance between the camera and her subjects, and showing mother and children in a range of attitudes. Although this image was not the only shot of this series to be published, it has come to sum up how many Americans imagine the Depression. Lange herself (1895-1965) was initially unsure which exposure communicated most effectively. The title was also added later. In short, the cultural impact of this photograph developed over time, and was realized only in competition with the other exposures. Why did this one win out over the others, in public memory?

Drawing upon a long tradition of Christian Madonnas and nurturing women who bear the woes of humanity, Migrant Mother frames the realities of the farm Depression selectively. The shot eliminates the surroundings in a tightly framed close-up, removing any specific context in favor of a generalized image of stoic endurance. The children are obscured as they bend into their mother's sheltering body. Her lined and weathered face suggests the condition of the land itself, eroded by wind and drought. Her worried gaze solicits our sympathies without addressing us personally. The absence of a male figure increases the sense of women and children bereft and vulnerable, without a breadwinner. The universal appeal of Migrant Mother is thus a product of the selective framing of the circumstances in which it was made.

Ironically, later generations have brought other meanings to light. Florence Thompson, we now know, was of Cherokee Indian ancestry, a fact that transforms the image in ways unintended by Lange herself. A century earlier the Cherokees migrated west on the "Trail of Tears," the forced exodus of Native farmers out of Georgia to the unoccupied lands of Oklahoma. In the Depression, "Okies"-some of them, like Thompson, descendants of the Cherokee migrated to California. In Lange's iconic image, this historical sediment remains buried, only recently brought to light by researchers interested in the woman behind the myth.

Margaret Bourke-White and Walker Evans: Documentary Extremes

A significant subgenre of documentary was the photo book, a series of photographs captioned and accompanied by a text. Pairing photographers with writers or sociologists, these books directed the meaning of the image through words and through narrative sequencing. The photo book raised issues about documentary truth and objectivity more pointedly than the individual image: intended to "demonstrate a thesis," the book form provoked concerns that the photographer's subjects could be manipulated, and the image itself selected and framed, to prove a point. The photo essay became a staple of the postwar photographic journalism of Life magazine, though it was maligned by some as a form of mass persuasion that played on popular emotions. The two early examples here exemplify the spectrum of approaches inherent in the genre.

YOU HAVE SEEN THEIR FACES. Among the more controversial photo books was Margaret Bourke-White and Erskine Caldwell's 1937 You Have Seen Their Faces (fig. 16.22), a relentless vision of rural poverty that presented its southern sharecroppers as the wretched victims of a corrupt southern society, deprived of dignity and incapable of managing their lives. White and Caldwell saw themselves as social activists exposing particular truths in order to promote programs that would improve the lives of those they depicted. To do so they resorted to putting words into the mouths of their subjects and selecting the most extreme examples of hopelessness. The images used dramatic angles and lighting to provoke a particular response . Their approach to documentary disturbed others who recognized the unequal nature of the encounter between documentary photographer (educated, urban, and often backed by government authority) and his or her subjects, whose lives were frequently made to illustrate particular lessons. Bourke-White (1906- 71) and Caldwell (1903- 87) were not alone in facing charges of staged or manipulated subject matter in order to promote certain "truth effects." In one notorious episode, an FSA photographer, Arthur Rothstein, was exposed for using a cow skull as a movable prop in various photographs- a convenient symbol for capturing the desolation of the water-starved region he was sent to photograph. Today, in the wake of Photoshop and other programs that digitally manipulate the photographic image, such minor alterations of the documentary subject might seem innocent enough. But they violated public trust in the unaltered truth of the photograph.

LET US NOW PRAISE FAMOUS MEN. Walker Evans's collaboration with the writer James Agee (1909- 55) in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (fig. 16.23) took a very different approach to 1930s documentary. Evans's (1903-75) photographs of three southern sharecropper families offered a less manipulative kind of documentary: a respectful and sustained visual record of the lives, homes, and personal possessions of the poor. Endowing them with specific identities and painstakingly engaging the intimate realities of their lives, Evans's photographs and Agee's text insisted on the everyday dignity of those whose identities had been erased by the generalities of social science and federal programs intended to address the problems of rural poverty. Floyd Burroughs and his daughter Lucille meet our gaze, sitting on their immaculate but worn front porch. This is their space, into which Evans was invited as a guest. The frontality of Evans's photographs refuses to impose a point of view beyond the realities of the moment. Occasionally however, Evans did move furnishings around in order to impart a sense of order in the most humble interiors.

Evans departed from much 1930s documentary practice by refusing to use captions in his work, which was often presented in book form, as in his American Photographs. He resisted any form of scripting, insisting instead on the mute witness of the visual record itself. Yet Evans had an understated irony, conveyed through sequencing of images in the book or juxtaposition of details within the frame.

Despite his success, Evans remained a controversial figure throughout the 1930s; he worked briefly for the FSA, resisting the ways in which photographs were often made to serve a preordained set of meanings. Ansel Adams, a member of f.64, found Evans's frequently barren, marginal, or dejected subjects sordid and insulting to an American sense of pride; others were offended by his preference for the homely; the marginal, and the cast-off, reading his images as critical of national culture. Houses and Billboards in Atlanta (fig. 16.24) documented the strange meeting of dingy house facades with images of a glamorous mass produced urban culture. The gulf separating Hollywood from real lives was a recurrent theme of both painting and photography in these years.

Evans expanded documentary means, bringing the formalist approach of modernist photographers to an engagement with the ways in which places and things reveal history and culture. By emphasizing the act of "seeing," Evans and those he influenced reconciled a commitment to straight photography with efforts to broaden photography as an expressive medium. As another documentary photographer from the 1930s, Berenice Abbott (1898-1991), put it succinctly, "Photography ... teaches you to see."15