12.2: The Road to Abstraction

- Page ID

- 232337

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Another current of artistic innovation, grounded in abstraction, emerged alongside of twentieth-century urban realism. Abstraction was perhaps the fundamental feature of aesthetic modernism. Several developments opened the way. In the aftermath of urbanization and colonial expansion into the non-industrialized world, modernist movements found inspiration in the arts of supposedly rural "folk" and preindustrial "primitive" cultures. Writing in 1901, the photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882- 1966) expressed a disaffection felt by many: "now that we have reached the acme of civilization with our fire-proof skyscrapers and our millions of spindles, it still remains to climb to the height of artistic achievement reached by the Zuni and the South Sea Islander."7 Coburn's comment inverted customary hierarchies; the "primitive" was now the most aesthetically advanced. This attitude was symptomatic of the realignment of values in early modernism. Encountering these cultures, metropolitan artists set aside their own representational conventions and traditions, rooted in naturalism and realism, and found fresh inspiration in the abstraction and ritual functions of non-Western art. The Arts and Crafts movement (see Chapter 10) had anticipated trends in the early twentieth century when it repudiated the products of industry and mechanization, turning instead to Native American textiles, baskets, pottery, and other handmade objects. The geometric abstraction of Native American arts in pottery and weaving furnished an American parallel to the "primitive" arts of Africa that catalyzed European modernism.

The first phase of this turn away from Western sources was the fascination with Japanese arts (known as Japonisme-see Chapter 10) dating from the late nineteenth century. The career of Arthur Wesley Dow (1857- 1922) connects the late nineteenth with the early twentieth century in several respects. One of the primary tenets of artistic modernism was the assertion of formal values over and above the claims of truth to nature, or illusionism.8 Through his teaching, his practice, and his published work, Dow influenced numerous young painters and photographers who would later emerge as leading modernists, including Georgia O'Keeffe (who wrote of Dow, "This man had one dominating idea: to fill a space in a beautiful way"), and Clarence White (1871- 1925), who taught some of the leading young photographers of the 1920s and 1930s. 9 At Columbia Teachers' College in New York City, Dow's teaching was grounded in the lessons he had learned from his study of Japanese art. A disciple and student of the Harvard scholar of Japanese art Ernest Fenellosa (see Chapter 10), Dow helped to shape American modernism through his book Composition (1905), which transformed admiration for Asian art into principles that could be taught. "I hold that art should be approached through composition rather than through imitative drawing," he wrote. 10 Beginning with the fundamentals of Japanese woodblock, his teaching emphasized formal simplification, attention to the harmonious organization of lights and darks (which he referred to through the Japanese concept of notan), absence of illusionistic perspective and chiaroscuro, and emphasis on surface design (fig. 12.12). But his sources reached beyond the art of Japan to include Native American design. Dow and others of his generation found in Native art not only a new use of line and color abstracted from the need for describing the world, but one that had a specifically American stamp appropriate for a generation seeking to define a distinctly American brand of modernism. Dow's student Max Weber (1881-1961) exemplified the range of influences on this first generation of modernists, from Asian and Native American to the arts of Africa, which he examined in the museums of Paris during his studies there from 1905 to 1908 (see fig. 14.12).

Dow was among the first to use music to assist his students in abstract visualization-a method that would become standard in many art schools. Synaesthesia was the principle that the properties of sound and color-aural and visual-produce parallel aesthetic effects, an idea familiar to nineteenth-century Romantic and Symbolist artists, and one that would provide an important road to abstraction for early modernists such as Georgia O'Keeffe and the Synchromists (for more on synaesthesia, see Chapter 10). Along with the shared notion of harmony that united music and color, musical qualities of rhythmic repetition and counterpoint came to be recognized as elements of form in all the arts, from dance to sculpture to poetry. The idea that music was the most purely abstract art form helped free the visual arts from their referential basis in nature, and stimulated the growth of abstraction in painting.

Cultural Nationalism/ Aesthetic Modernism: Alfred Stieglitz

Guided by such critical voices from the nineteenth century as Walt Whitman and Louis Sullivan (see Chapter 11), many among those exploring new art and literary forms felt that American culture had failed to produce a national expression worthy of the young democracy. By 1913, the summons to a revived cultural nationalism following the cosmopolitanism of the late nineteenth century had spread across a range of publications and personalities. Cultural nationalism was the belief in cultural forms as uniquely expressive of the nation-its democratic heritage, and its freedom to forge a new language attuned to contemporary realities, without the restrictions of traditions and conventions. And within the tenets of cultural nationalism, a central figure in this process was the creative artist- form-giver to the new.

A key figure in this early-twentieth-century "cultural renaissance" -as artist / intellectual, gallery owner, and tireless promoter of the new American modernism-was Alfred Stieglitz (1864- 1946). Born in Hoboken, New Jersey, of a German Jewish family, Stieglitz had discovered photography as an engineering student in Germany. By the 1890s, he was exhibiting internationally, and established himself as a chief exponent of photography as an expressive art. With the zeal of a missionary and a charismatic power that won many followers, Stieglitz expanded his interests well beyond photography to include the latest developments in European and American modernism.

Disney's Fantasia: Middlebrow Modernism

MODERNISTS CLAIMED a privileged status for music because it was a fully abstract medium. That status came under siege with Walt Disney's Fantasia (1940-1). Considered today to be Disney's masterpiece, Fantasia took excerpts from the canonical works of the classical music tradition-from Bach's Toccata and Fugue in D Minor to Beethoven's "Pastoral" Symphony, Tchaikovsky's Nutcracker, and the works of many other mostly nineteenth-century composers-and set them to animation, giving them a storyline and a narrative structure. The intention of Fantasia was to broaden the audience for classical music (already a mission of Leopold Stokowski, the conductor featured in the film) by attaching stories to the music. However, highbrow critics attacked the film, arguing that it diminished the music and that animated narrative restricted music's suggestive richness. Fantasia also brought synaesthesia-an idea key to the emergence of abstraction-to a mass audience, with music evoking abstract visuals in one sequence at the beginning of the film (fig. 12.13). Fantasia even took the avant-garde music of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, which had so provoked Parisian audiences at its premiere in 1913, and used it to drive a compelling visual narrative of the natural history of the earth, bringing Stravinsky's musical primitivism and percussive power to an audience largely uninitiated into musical modernism.

Besides disrupting the autonomy of the music with images, Fantasia also extracted parts from a larger whole, a kind of Reader's Digest or "Greatest Hits" approach to classical music. In place of introspection and absorption was distraction-an ever-changing stream of images and musical excerpts. Such pabulum, so the critics argued, spoon-fed audiences who resisted the rigors of refined taste. Fantasia thus found itself at the center of a debate about just how far cultural producers could go in making high art accessible to mass audiences before the very character of the art was itself in peril.

STIEGLITZ AS GALLERY OWNER. Stieglitz's role as self appointed spokesman for the new American art took shape most fully through his activities as a gallery owner at 291 Fifth Avenue, dedicated first to photography (the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession) in 1905, and then, as Gallery 291 , to modern art, from 1907 until its closing in 1917. It was at Gallery 291 that young American modernists were exposed to the new art in a series of one-person exhibitions-the first of their kind in the United States-of artworks by Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957), and Henri Rousseau (1844-1910), among others. In 1911 Gallery 291 presented what it claimed was the first one-man exhibition of Pablo Picasso (1881- 1973): eighty-three drawings and watercolors, later offered to the Metropolitan Museum for two thousand dollars (and refused). Pursuing other sources of European modernism, Stieglitz presented a series of exhibitions featuring children's art, which embodied a sense of naive wonder and intuitive form that he cherished, as well as African sculpture. For Stieglitz, European modernism was a critical resource for an evolving native expression; eager to keep abreast of European developments, he sent the young photographer Edward Steichen (1879- 1973) to Paris, where he made direct contact with artists and secured exhibitions for 291. It may seem odd that a man dedicated to fostering an American art would devote so much energy to presenting and promoting European modernism. Yet Stieglitz saw Gallery 291 as a laboratory-a place vitalized by the most recent transnational artistic and intellectual currents, a space for animated talk and debate, within which artists of all persuasions would come to learn from others, and to experiment with new expressive forms. Encouraged by him to work independently, the artists Stieglitz nurtured quickly developed their own language. His greatest success lay in his openness to new ideas, and his resistance to all art doctrine and dogma. Believing above all in the creative spirit unfettered by received ideas or traditions, Stieglitz felt the best way to foster an authentic national art was to carve out a space where his artists could develop their own creative instincts, free from the-pressures of the market. Here they would wed modernist form to American subjects.

STIEGLITZ AS MAGAZINE PUBLISHER. Stieglitz expanded his mission to educate those interested in modern art through the magazine Camera Work, which he published quarterly. From 1905 to 1917, Camera Work shaped a generation of younger artists by presenting excerpts from the leading critics, artists, and philosophers of the modern movement, including the French vitalist philosopher Henri Bergson (1859-1941) and the Russian Expressionist painter Wassily Kandinsky (1866- 1944), whose essay On the Spiritual in Art offered a language for conveying the visionary properties of form and color. Camera Work published some of the leading essayists and critics in American photography, and staged debates between the Pictorialists, who developed a range of painterly effects, and the practitioners of the straight, or un-manipulated, print. Through its reproductions of paintings, drawings, photographs, sculpture, and prints, the magazine publicized new developments and spurred discussions about the relationships between various media.

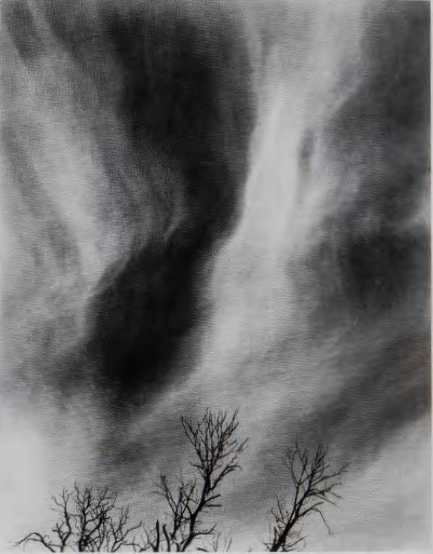

STIEGLITZ'S EQUIVALENTS. Grounded in the Romantic tradition of artistic self-expression, Stieglitz struggled to understand the new art coming out of Europe. In matters of philosophy, he himself had few new ideas. Many of his theories about art-along with the work of the writers and artists he mentored and promoted-represented a late expression of nineteenth-century Symbolism with ties to the Romantic movement. For Symbolists, meaning expanded metaphorically through the artist's imagination, drawing connections from the thing itself to a wider world of significance. "Art, for me, is nothing more than an expression of life," Stieglitz wrote. "That expression must come from within and not from without." This late Symbolist attitude is evident in Stieglitz's series of photographs known as Equivalents (fig. 12.14)-a sequence of cloud portraits, in which endlessly shifting patterns, densities, luminosities, and variations of light and shadow suggest a chronicle of moods or transitory mental states. This correlation between nature and inner states of being was the essence of Symbolist expression, and it proved a supple language for an emergent cultural nationalism that sought analogies in nature to express creative inspiration.

Stieglitz and His Circle

Throughout his life Stieglitz remained strikingly consistent in his preference for a modernism rooted in expressive abstraction. He remained loyal to a small group of artists with whom he was closely associated throughout their careers: Marsden Hartley (1877-1943), Arthur Dove (1880-1946), John Marin (1870-1953), and Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986). There were others who came into his orbit at various times, including Edward Steichen, Paul Strand (1890-1976), and Charles Demuth (1883-1935). But Stieglitz's domineering personality, and intolerance for any form of artistic activity involving commerce or the business of buying and selling, made for many broken alliances in the course of his career.

The circle of artists and critics that formed around Stieglitz was marked by its focus on a "native" or homegrown art summed up by the phrase "soil spirit." Coined in 1922 by a critic who disdained their personal and highly subjective language, the term "soil spirit" nonetheless captures the nature-based organic abstractions of Dove and O'Keeffe.11 Reaching its fullest articulation after 1917, this alliance of artists was formed by the varied strands of native and international artistic discourse, placed in the service of a self-proclaimed new American art. Stieglitz's high-minded attacks on "Philistines"-profit-minded businessmen insensitive to aesthetic values- echoed his efforts to remove art from the corrupting influences of modern life. The artist as visionary was a stance that preserved creative autonomy apart from any identification with commerce, mass media, and industry.

Stieglitz's version of American modernism differed from those of the artists and writers who embraced the pounding intensities and fractured sensations of urban life. These artists-the subject of the next chapter-felt that technology was the primary condition of their time, and they sought ways to express modernization through their art. These two factions of artists represent the extremes between which modernist practice in the United States took shape.

The Lyrical Left

THE " LYRICAL LEFT" is a term coined by the historian Edward Abrahams for those artists, writers, thinkers, and social activists who believed that the task of transforming society began with transforming the self. Creative expression was one avenue to self-liberation. The lyrical expression of the soulful self-through dance, prose, poetry, and image-making-went hand in hand with efforts to rethink conventional social and gender attitudes. These included relations between men and women, newly restructured to embrace sexual and social equality. Campaigns for birth control and women's rights found their place in the lyrical left, alongside activism on behalf of workers' rights to organize against the paralyzing drudgery of industrial work. Ultimately the lyrical left encompassed a broader, native-born, socialist critique of a business culture that generated militarism, imperial conquest, and war. The lyrical left reached across widely differing artistic camps, taking in both the Ashcan artists and the Stieglitz circle. It involved artists in social causes, and it cut across class lines, bringing together Fifth Avenue matrons with Wobblies (members of the International Workers of the World, led by "Big Bill" Heywood), and the sons and daughters of old eastern elites with immigrant workers. For a brief few years, before World War I shut down the galleries, coffeehouses, and salons of the lyrical left, these men and women brought together the personal and the political, exploring new ways of living and loving, of working and creating, that furnished a model and an inspiration for later generations committed to transforming self and society.

ORGANIC ABSTRACTION: ARTHUR DOVE. "I look at nature, I see myself. Paintings are mirrors, so is nature."12 Since the Romantic Movement of the early nineteenth century, nature had offered spiritual refuge for those unsettled by the rapid pace of historical change. The first generation of American modernist abstraction faced in two directions. For the artists around Stieglitz, organic abstraction responded to modernity by returning to the slow, sustained rhythms of the natural world. Even when they painted the city, they imbued its tall buildings and clangorous environment with the vital energies of natural, living things. Collectively they searched for an American art grounded in nature, intimately known and part of the nation's living past.

Organic abstraction, as practiced by Arthur Dove, expressed a growing reaction to mechanization and the analytic thrust of modern science. Drawing on a fascination with biology, it took its inspiration from plant forms, the ebb and flow of water, the dilating light of a sunrise, the universal force of growth and creation charging the world of matter, expressing in turn the rhythms and sensations of the body. Though indebted to such contemporary European thinkers as the French philosopher Henri Bergson-whose work was widely read-Dove's thinking was also shaped by older organicist philosophies traceable to the nineteenth-century American writers Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803- 82) and Henry David Thoreau (1817- 62). Like them, Dove looked to nature, informed by imagination, for a renewal of vision, finding there a bridge between self and world, matter and spirit. Very much in the American grain, organic abstraction offered an avenue into nonrepresentational art that was grounded in earlier American arts and letters. In Dove's Alfie's Delight (fig. 12.15), overlapping orbs of variegated earthy colors form petal-like ridges suggesting floating protoplasmic forms. These pulsate in a vaguely defined space of nature, simultaneously expanding and contracting as they recede toward a horizon and then funnel energies back toward the donut-like shape at the right center. A serpentine blue suggesting a river flows across and behind the concentric horizons of receding disks. In the lower left-hand corner a sulfurous yellow wash bleeds into the canvas, running and ridging to create different densities. At other points the viewer can discern Dove's graphic underdrawing as well as the track of the paintbrushes he used. Despite the appearance of accident, he skillfully orchestrates different densities of color, from the veil-like yellows to the intervals of impenetrable black, balancing the decorative shapes on the surface against the suggestion of a natural space.

Dove began his artistic career as an illustrator, taking up oils at the instigation of John Sloan and William Glackens. He quickly moved from clear debts to Post-Impressionism, in his first paintings of 1907-8, to a type of abstraction in which natural and vegetal forms are disciplined into rhythmic curves and volumes, suggesting the biological principles of ordered growth that fascinated him throughout his life. Through most of his career he avoided New York City, living instead in physically difficult circumstances in which the landscape of sea, shore, and woods was an immediate and real presence. Dove wished, in his words, "to enjoy life out loud," and wanted to convey a sense of nature unmediated, as if experienced through his pores.13

Dove's early abstractions at times suggest the exuberant energies of Art Nouveau, bursting into convolutions and spirals, as in Nature Symbolized, no. 2 (fig. 12.16). They appear larger than the small dimensions of the paper itself; the same invisible energies animate both self and universe. These early abstractions (from 1910 on) coincided with the Russian Wassily Kandinsky's movement into pure abstraction, suggesting the simultaneous but independent "invention" of abstraction on both sides of the Atlantic. The question of priority-who did what first-is perhaps less important than the fact that many artists in these years were thinking about abstraction from nature.

In his assemblages of the 1920s, Dove incorporated nature very directly-in the form of dried flowers, wood, sand, and twigs-into his abstract compositions. Ralph Dusenberry (fig. 12.17) is a portrait of his Long Island neighbor, a high-spirited handyman, carpenter, and roustabout. Juxtaposing found objects-wood shingles, a folding ruler (alluding to Dusenberry's carpentering), and sheet music- against a painted canvas background, Dove evokes the man with humorous affection. Dusenberry was a legendary swimmer who could dive into the Sound like a kingfisher (suggested by the vector-shaped shingle). When "liquored up" he was known to sing a traditional hymn ("Shall We Gather By the River"), a fragment of which is pasted on the lower edge of the work. Dove pays tribute to his neighbor's homegrown "all-American" qualities and patriotism with a fragment of the flag. His collage resembles the manner in which the American modernist composer Charles Ives (1874-1954) used musical fragments of hymns and popular band music, woven into an orchestral tapestry that nonetheless preserved their identity. Found objects in Dove's assemblages of the 1920s act in a similar fashion, retaining their "thingness" (Dove's own label for these works was his "thing paintings") while creating new meanings through juxtaposition with other objects.

GEORGIA O'KEEFFE. Georgia O'Keeffe's career-long meditation on landscape and nature resembled Dove's in its turn away from the city as the focus of a native modernism. O'Keeffe was born in Wisconsin in 1887; her early training as an artist coincided with the waning years of the genteel tradition in the arts. In the artistic output of 1900 to 1910, a tonalist sensibility of vague contours, blurred by twilight and mist, of muted pigments and indefinite forms, gave way to a cleansing new intensity of vision. O'Keeffe's work, breaking into abstraction in 1915, embodied this new attitude fully. She was, as Marsden Hartley put it, "modern by instinct."14

Modern by instinct perhaps, she nonetheless required a long period of tutelage before arriving at her own visual language. She was conventionally trained, first at the Chicago Art Institute and then at the Art Students' League in New York City under William Merritt Chase (1849-1916). While she later expressed her admiration for Chase, his painterly style, which she initially emulated, was still based on transient optical effects of light and shadow, which she would later renounce. In the dauntingly vast and uncluttered landscape of the western Plains, where she traveled to teach in 1915, she distilled various influences into a new language of abstract forms. In a series of watercolors done in 1917, she cultivated the willful accidents of the medium (uneven transparency, bleeding, and ridges of pigment), as well as the appearance of naive drawing (fig. 12.18). In Arthur Wesley Dow's classes at the Columbia Teachers' College, O'Keeffe drew from music and learned to visualize abstract form. Into the late 1910s, O'Keeffe continued to find visual inspiration in sounds; cattle lowing on the Texas plains at sunset became a piercing arc of intense color breaking the horizon in Red and Orange Streak (p. 390 ). Although she always denied outside influences on her work and insisted that it expressed a personal experience of the world, O'Keeffe read widely, in literature, contemporary philosophy and drama, and art criticism. Through Camera Work she became informed about the most recent intellectual and artistic developments in modern art. Breaking free from older ways of painting was also her personal declaration of independence; she later explained that as a woman, having few freedoms in other areas of her life, she determined to paint in her own way, following no one else's rules.

Returning to New York in 1917, O'Keeffe began a professional and personal involvement with Alfred Stieglitz that lasted until his death in 1946. Her relationship with the foremost promoter of modernism brought other new influences on her art as well, through the male painters surrounding Gallery 291. From the photographer Paul Strand, O'Keeffe learned a modernist strategy of focusing on the detail isolated from the larger whole, prompting a fresh new vision of the already known. She advised a young artist in 1933 to paint as though, Adam-like, he were the first to see the world.

O'Keeffe refused the organizing distinctions between abstraction and representation; as her companion, Juan Hamilton, put it after her death in 1986, for O'Keeffe they were one and the same.15 The genres that had organized nineteenth-century painting-landscape, still-life, and portraiture-ceased to have meaning for her, as she painted land-forms with the intimacy of still-life, and fruit and flowers on a scale that resembled the forms of the earth.

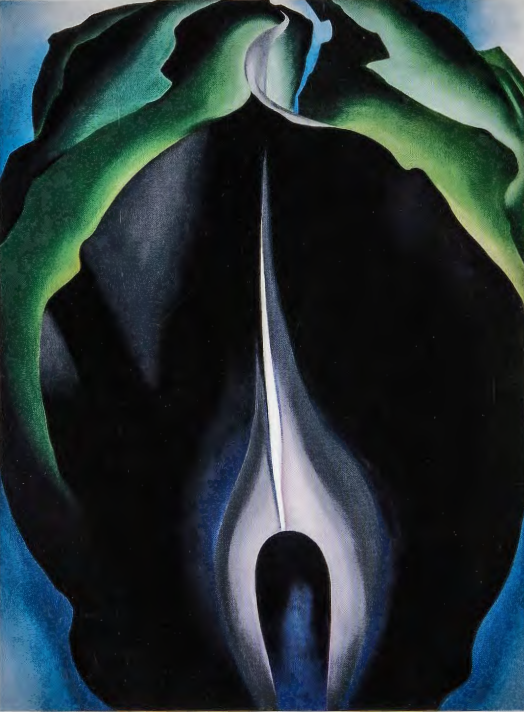

In the 1920s, O'Keeffe began painting flowers, a subject that brought together a number of her artistic concerns. Flowers were traditionally associated with amateur female painters, but O'Keeffe painted flowers as never before, with petals pressing at the boundaries of the frame, their sexual parts looming out of shadowy interiors. She chose colors of garish intensity-"magnificently vulgar," in her own words. 16 Jack-in-the-Pulpit is a series of six paintings of various dimensions, which begin with an exterior view of the flower, gradually focusing in on the interior configuration of stamen and pistils. The fourth of this series (fig. 12.19) explores ambiguities of scale and reference; the interior is magnified to fill the entire canvas. Interior and exterior, space and mass, float in and out of one another; concave becomes convex. At the four corners of the painting, a deep blue suggests the void of space surrounding the central motif. The profound black of the central petal reads as an interior void, penetrated by the slender flame-like form. The dark form of the pistil retains this ambiguity, becoming now a phallic projection into a pale void, now a cavernous space. Such formal ambiguities parallel sexual ambiguities-simultaneously male and female , O'Keeffe's imagery carries an androgynous quality that resists efforts to read it solely in terms of feminine experience, readings that O'Keeffe herself vehemently rejected. Such sexualization of her paintings, she felt, denied their full metaphorical range, from body to nature and landscape. Metaphor-understanding one thing through the experience of another was central to her art. Like much of O'Keeffe's best work, Jack-in-the-Pulpit preserves this ambiguity, bringing us to view the already known and familiar in a new way.

O'Keeffe's career and marriage to Stieglitz confined her to New York City through the 1920s. In 1925, she and Stieglitz moved into the upper stories of the Shelton Hotel, where she commenced a series of New York cityscapes and skyscrapers (see Chapter 14). In 1929 she traveled to New Mexico at the invitation of Mabel Dodge, former hostess of the New York avant-garde turned Taos earth mother. The move was the beginning of O'Keeffe's deep love affair with the region, and it gave birth to the second phase of the O'Keeffe myth, the one that has fused artist and place into one powerful cultural image. Integrating the various threads of her art through the 1920s, O'Keeffe discovered new subjects: pelvic bones opening into blue voids; rams' skulls floating above the wind-carved earth of northern New Mexico. Starkly beautiful records of self-imposed desert exile, O'Keeffe's forms cut through our cluttered visual environment and engage us in the meditative act of seeing, as if for the first time.

STIEGLITZ AND O'KEEFFE: "LOVE IN THE MACHINE AGE."17 The artists of the Stieglitz circle were deeply influenced by changing attitudes about sex and the body. In the 19ros and 1920s Americans discovered Freud's theories of sexual repression, which fueled the desire among modernists to free current cultural mores from lingering puritanism and to pursue a new candor in matters of sex. Indeed, sex became a kind of sacrament for the modernists, drawing an overly rationalized culture back to fundamental forms of experience (what Benjamin de Casseres, an associate of Stieglitz's, termed "The great American sexquake").18

This infatuation with the liberating potential of sex helped shape a new brand of American art criticism, best exemplified in the writings of Stieglitz's acolyte Paul Rosenfeld (1890-1946). Rosenfeld found in the works of both Dove and O'Keeffe a forthright expression of unfettered physical and sexual sensation. About Dove he wrote: "A tremendous muscular tension is revealed in the fullest of the man's pastels .. .. A male vitality is being released .... And in everything he does, there is the nether trunk, the gross and vital organs, the human being as the indelicate processes of nature have shaped him."19 O'Keeffe, by contrast, "gives the world as it is known to woman."20 Rosenfeld saw her art in terms of feeling: O'Keeffe exposed women's sexual feelings to men. His heated rhetoric was fueled by Stieglitz's nude studies of O'Keeffe in post-coital relaxation ( one phase of a series of photographic portraits that spanned the years 1917 to 1935), which caused a minor sensation when they were exhibited in 1921, flooding the gallery with curiosity-seekers drawn to images of the young artist "Naked on Broadway." Helped along by the criticism that flowed forth from the excited pens of critics, O'Keeffe's modern vision and inner selfhood- linked to her sexuality-proved to be a highly marketable commodity. Yet the discourse of modernism worked differently for men than for women artists. Dove was never narrowly defined by his gender. O'Keeffe's male critics, by contrast, conflated her sex with her identity as an artist. In their terms, being a woman was an experience that shaped and conditioned all that she did and thought. Her sex was-in their eyes-the primary determinant of her art. Modernism's embrace of the sexualized body, grounded in nature, broke dramatically with the genteel tradition and its insistence on drawing a firm boundary between the human and the natural worlds.

Vision as Meditation

IN THE MINDS of some critics, the accessibility of O'Keeffe's images and her popularity with the public pushed her accomplishments to the margins of "serious" art. For example, Clement Greenberg (1909-94)-a leading American art theorist beginning in the late 193os-believed that "true" modernist painting developed toward the purest expression of the medium itself: paint on a flat surface, working against illusion and banishing all references to anything beyond the canvas. For Greenberg, modernist painting should exist as an object, to be perceived instantaneously in its entirety, without recourse to the dimensions of narrative, time, or space. "[T]he whole of a picture should be taken in at a glance; its unity should be immediately evident."21 Greenberg's modernist ideal represented a flight from temporal duration, and from the embodied condition of the viewer, qualities that he associated with O'Keeffe.

However, in contrast to Greenberg's insistence on reductionism, O'Keeffe stands at the head of a long line of modern American artists, filmmakers, writers, and poets whose work is concerned with the actual unfolding of perception within the body and across the surfaces of nature. Critical of an increasingly managed and programmed world, these artists celebrate the sensuous reality of nature and resist the separation of vision from the other senses. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, such concerns have taken various forms. In the post-World War II years, the Beats and the post-Beat generation looked to eastern philosophies-Zen Buddhism in particular-to restore the moment to its place within a continuum of perception. Beginning in the 1960s, experimental film used the motion picture camera to turn the tradition of montage and fast-paced editing on its head. In long, unedited, meditative takes, the camera pursued its own singular monotony of vision, transcribing rhythms and sensations of the body. This exploration of perception-unfolding through time and as a result of the body's movement through space-formed an element in artistic developments as diverse as Minimalism (see fig. 18.10) and performance art (see fig. 18.11), with its redirection of attention beyond the purely ocular to the senses of smell, touch, taste, and hearing. By activating all the senses, these artists reconnected sight to the impulses, desires, and memories of the body.

In a form of what the writer Malcolm Cowley called "carnal mysticism," sexuality and physical life became the avenue to transcendence.22 Nevertheless, while announcing a greater sexual freedom for women, these new attitudes still resisted the idea of women as self-formed creators and producers of culture.

Although Stieglitz renounced the commercialization of art in the strongest terms, -the income from the sales of O'Keeffe's paintings-assisted by the sensationalism of his nude photographs of her-kept his galleries afloat in the 1920s and 1930s. Despite his insistence that he was above crass commercialism, Stieglitz was quick to use the tactics of modern marketing. Knowing that "sex sells," he actively endorsed the view of O'Keeffe's art as an expression of her carnal knowledge. The seductions of fame were hard to resist. Fame, however, came at a cost for O'Keeffe, as she found herself and her art confined by a critical discourse that linked creativity to gender. If her expressive power came directly from her womb, as critics claimed, then the artist herself was denied the very powers of original invention that defined the heroic male modernists around her.

AN ORGANIC EXPRESSIONIST: JOHN MARIN. Organic abstraction lent itself not only to subjects from nature but also to those from the city, a central preoccupation in the long career of John Marin. His watercolors and paintings of the city captured the roiling, vital energies of both natural and man-made landscapes. From his emergence as a mature modernist in the 1920s, Marin was widely considered among the leading American artists of the first half of the twentieth century His work and the responses to it teach us a great deal about the emergence of a peculiarly American language of image-making.

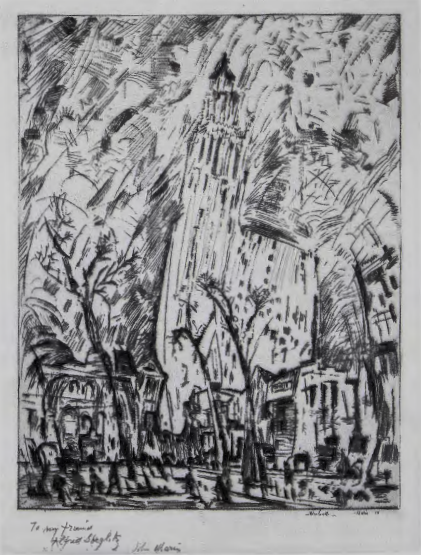

Returning from several years in Europe (1905-11), where he practiced a delicate Whistler-influenced Tonalism, Marin responded to a rapidly modernizing New York with a new graphic style of slashing diagonals-"explosions of line and color," as his patron Duncan Phillips put it-and rapid brushstrokes suggesting the accelerating tempo of the city. Marin insisted that American subject matter had to be married to a new visual language capable of expressing a new culture. In his etching of the Woolworth Building, subtitled The Dance (fig. 12.20 ), the forms of the city sway and pulsate: " ... the whole city is alive; buildings, people, all are alive; and the more they move me the more I feel them to be alive."23 The skyscraper is shown "pushing, pulling, sideways, downwards, upwards," as he explained in a statement of 1916. He imagined the city animated by the organic energies of nature. In Lower Manhattan (Derived from Top of Woolworth Building) (fig. 12.21), a yellow paper cutout sun, sewn onto the bottom of the watercolor, establishes the radiating spokes of the composition within a black charcoal nimbus. The sun stands in for the artist, organizing urban chaos into dynamic equilibrium. Marin disintegrated solid masses and charged space with new drama. For critics and audiences, he substituted natural for mechanical dynamism, rescuing the modern city from its associations with the brute force of the machine. The result was a form of personal expressionism linked to the visionary optimism of Walt Whitman and others who embraced the vital energies of modern life.

Marin presented himself as a na"if, writing in broken sentences, painting ambidextrously with the fingers of both hands, and drawing directly with the brush. Watercolor appealed to him for its immediacy of communication. His patron Duncan Phillips called him "a bold adventurer of the moment's intuition," reaffirming a deep-seated image of American individualism.24 Dividing his time between the environs of New York and the shoreline of Maine, Marin alternated between depicting urban subjects and landscapes of nature. In this and many other ways, he spanned a generation's divided consciousness, resolving contradictions between the mechanical and the human, the future and the past, the city and nature.