12.1: Early-Twentieth-Century Urban Realism

- Page ID

- 232336

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)In the first decade of the twentieth century a group of urban realists in painting, prints, and sculpture took on new immigrant and working-class subjects that the previous generation had considered inappropriate to the fine arts. These realists humanized the titanic new forms of the city by engaging street-level views of people interacting with one another, in everyday encounters, displaying a range of behaviors that set them distinctly apart from the middle class. Urban realists found their art in the spectacle of the immigrant slum, as well as in the new urban entertainments, young working-class women, domestic arrangements, and new forms of sociability that animated the ethnically diverse metropolis. Painters and sculptors both, they were not stylistically radical; indeed, they drew upon long-established traditions of European realism, from the seventeenth-century Dutch artist Frans Hals, to the Spanish artist Diego Velazquez-an important influence on the previous generation as well-to the nineteenth-century French satirist Honoré Daumier, whose lithographs scourged the pretensions of wealth and power. Their modernity came not from the form of their work but from their subject matter, from their rapid style of execution, which embodied the pace of urban experience, and from the incorporation of new urban viewpoints into their work.

Modernism/ Modernity/ Modernization

THESE THREE TERMS-modernism, modernity, and modernization - have specific applications not interchangeable with those of the others. The root of all three is the word "modern," derived from modo, a form of the Latin word modus meaning "just now" or "very recently." In art, modernism refers to a style encompassing a wide range of formal practices that began in explorations outside of the art establishment in the later nineteenth century, but which eventually became institutionalized in art. While modernism emerged out of European culture in the late nineteenth century, it fed off forms of cultural modernity that were taking shape on both sides of the Atlantic. Modernity refers to an epoch in cultural history that some historians date back as far as the sixteenth century, and which is marked by movement toward scientific rationalism, the growth of large-scale social institutions, and the transformation of production by mechanization. Modernization refers to the active process of social change caused by the technological transformation of production, usually producing a sense of shock and dislocation among those caught up in it. Postmodernism demarcates the end of the modern era and a dismantling of the Enlightenment belief in a centered subjectivity that organizes the world through rational structures.

What united the urban realists with their modernist contemporaries was an attitude of rebellion against the polite world of late-nineteenth-century art and its preoccupation with aesthetic refinement and exclusive focus on the world of privileged urban elites. Central to the movements of renewal within American art of the new century was the value of authenticity-a quality associated with direct expression, immediacy of execution, and a new emphasis on the truth of the first impression, seized and translated into paint with all the force of an intuitive emotional connection. These new urban realists renounced skillful drawing, finish, and the ability to reproduce the outward appearance of things-all tenets of the accepted art of the National Academy of Design in New York, the nation's premier institution for promoting and exhibiting American art. Robert Henri's emphasis on direct expression was reinforced by the experience many of these artists gained by working for urban newspapers before taking up art full-time. In the years before the rise of photography, squadrons of mobile illustrators captured the sensational events of the daily urban scene. Their quick on-the-spot sketches were translated into line engravings. This kind of visual journalism schooled them in the art of visual drama and immediacy.

The Ashcan Artists

In the art of the urban realists, authenticity came to be associated with the subject matter of the foreign immigrants who had been changing the character of lower Manhattan from the late nineteenth century onward. Along with an older population of poor Irish-present in New York since the 1840s-were newer arrivals: Jews from Eastern Europe, Italians, Poles, Bohemians, and other rural Europeans uprooted from agrarian lives by hard times. Living in crowded quarters with far less privacy than other Americans were used to, these new immigrants-Catholic and Jewish rather than Protestant-spilled into the streets of New York with their strange languages, their odd dress and peddlers' carts, their different forms of worship and family life. Their otherness was both threatening and exhilarating to mainstream Americans, who reacted squeamishly to the dirtiness, poverty, and lack of privacy in the immigrant neighborhoods, a response earning those who painted them the label of "Ashcan" artists. Hailing from the Midwest or the urban centers of the East, the Ashcan artists were of English and French ancestry. They were drawn to the immediacy of life that distinguished these neighborhoods from the stilling conventionality of middle-class existence, and they embraced the urban immigrant lifestyle that seemed free from the oppressive codes of middle-class behavior. Exposure to the extremes of wealth and poverty in the new metropolis also aroused their political sentiments, driving some Ashcan artists toward social satire through the print medium, as well as toward direct political action.

ROBERT HENRI: "THE ART SPIRIT." The guiding spirit of these new artists was embodied in the figure of Robert Henri (1865-1929), an older artist whose teaching at the Ferrer School and the Art Students' League in New York influenced their art-making and helped shape the broader practices of twentieth-century realism. In 1908, reacting against the jury system of the National Academy, of which he was a member, Henri organized an exhibition of "Independents" at the Macbeth Gallery, comprising eight American artists ranging from the realists to urban impressionists and symbolists. As well as Henri, John Sloan, William Glackens, and George Luks, the group included Everett Shinn (1876-1953), Arthur Davies (1862-1928), Maurice Prendergast (1859-1924), and Ernest Lawson (1873-1939). Following the practices of French and German modernists in seceding from the official art establishments, Henri also astutely managed the publicity for the event, garnering much attention for his artistic cause.

Henri's teachings, assembled by his students and published in 1923 under the title The Art Spirit, are summed up by the paradoxical notion of cultivated spontaneity. "The original mood" inspired by the quality of life, he told his students, "must be held to."2 The trick was to capture the intensity of the original experience-a kind of raw data that was valuable in its own right. His catchwords, as the scholar Rebecca Zurier notes, were "energy, vitality, and unity," a unity achieved by a direct, visceral expression unfettered by traditional notions of beauty or technique. The quality of seeming uncomposed conveyed the impression of life experienced at firsthand rather than through the filter of artistic conventions. Rough, loose brushwork came to carry the rhetorical force of life itself. Through the vigor of his teaching Henri won a passionate following. One student, the art editor Forbes Watson, recalled how young manual laborers, having worked long hours, painted all evening under the eye of the master, and then slept on park benches because they could not afford a room. Henri shifted the focus of art from the aesthetic expertise of an elite to the idea that it was an ability possessed by all, needing only to be nurtured.

GEORGE BELLOWS. In his boxing paintings, George Bellows (1882-1925) graphically realized his teacher Henri's insistence on experience as the source of all great art. Bellows's Stag at Sharkey's (fig. 12.1) centers on two lanky male boxers engaged in an illegal prizefight. Tendons stretched to snapping point, they pummel one another, their faces buried in locked arms. The boxer on the right prepares to deliver a right jab while simultaneously thrusting a knee toward the groin of his adversary in a two-pronged attack. The second boxer lunges at his opponent, his body forming an extreme diagonal. Bellows heightens our visceral response to the scene with touches of red paint that evoke raw meat. Red also appears on the faces leering around the ring. The slashing, crude brushwork omits detail in favor of broad outline; faces border on caricature. The space of the ring is quite shallow; indeed, we become part of the audience, positioned in the third or fourth row from the ring, at eye level with others in the crowd. Rather than situating us at a genteel distance from the action, Bellows thrusts us into the fray.

While Thomas Eakins's (1844- 1916) paintings of sportsmen affirmed the power, beauty, and willed discipline of the male body (see fig. 11.13), Bellows's boxing paintings suggest a different appeal: from being a proving ground of physical and mental discipline, sport had become, by the early twentieth century, an arena in which to slough off the constraints of civilized life. The faceless anonymity of the boxers, the leering of the crowd, and the brutish nature of the match, all indicate masculine behavior far removed from the sunny precision of Eakins's rowers. Bellows's boxers act out a masculine contest of primitive strength and animality. The explosive energy of their bodies displaces them into an urban underworld of violent sport. Illegal prizefighting leveled the class and ethnic distinctions that prevailed in most other areas of American life by bringing together wealthy top-hatted men "slumming" for the night with rough workingmen, and by crossing racial and ethnic lines. The action draws the viewer in irresistibly, implicating us in the lusty animality of the scene.

Bellows's painting collapses the distinction between nature and culture-a distinction around which much late Victorian society was organized-in other ways as well. In the early 1900s, Bellows and his fellow Ashcan artists painted the city as a raw, disordered realm, from the animalistic behavior of his boxers to the literal bedrock on which the city stood. In his Pennsylvania Station Excavation (fig. 12.2), Bellows took as his motif the gaping hole in the fabric of the city where a great monument to civilized urban life would soon arise: Pennsylvania Station, a splendid Beaux Arts structure styled after imperial Roman architecture (see fig. 11.19). Unlike the American Impressionists, who focused on the glistening monuments and fog-shrouded elegance of the modern city, Bellows chose an ugly stretch of snow-covered earth. The surface of the painting is impastoed and scumbled; the city itself is pushed to the distant skyline, where it is dwarfed by the size of the hole extending back toward the horizon. The city is no longer defined in terms of opposition to nature, but as a new kind of nature; and urban progress as a process of violence and rupture.

JOHN SLOAN AND THE ACT OF LOOKING. The art of the Ashcan painters reveals another aspect of emergent urban culture: the act of looking. The crowded quarters of the new city offered rich new opportunities for voyeurism, intimate glimpses into curtained, lamp-lit interiors that transgressed the boundary between public and private. In John Sloan's (1871- 1951) etching Night Windows (fig. 12.3), a peeping Tom looks down upon a young woman preparing to go to bed, illuminated against the surrounding night. Another woman leans out the window directly below him. Sloan's city is a place of permeable boundaries between private and public. The urban environment of entertainment and consumption blurred differences between people- between "older Americans" and newer immigrants, proper ladies and "new women," leisure class and working class. Looking became a way to gauge one's distance, to reaffirm one's social existence in the anonymous environment of the city. Looks are everywhere in the Ashcan School-in the desiring gaze of shoppers, fueled by the lavish plate glass display of goods; in the eager spectatorship of moviegoers; and in the appraising glances of men at women loose in the city.

Sloan's Sunday Afternoon in Union Square (fig. 12.4) implicates his audience in the act of looking that is also the subject of his painting. Like the young men seated in the park, the gaze lingers, perhaps a moment too long, on a woman's back or well-turned ankle. Gazes cross and recross here, as young girls, who admire two strolling women, are themselves the object of the gaze of an older man on the park bench next to them. The subject of the working-class woman was new in American art, though it appeared earlier in the graphic media of mass-circulation journals. Often the child of immigrants, the working girl proved fascinating and unnerving for middle-class audiences. Sexually and, to an extent, financially independent, she embodied the transformation of urban culture and urban space in these post-Victorian years. With newly disposable income, she could move freely through the city with or without male escorts, put herself together with a range of stylish readymade clothing, and take in the new popular and mass culture of vaudeville and movies. Her flamboyant dress and behavior challenged bourgeois notions of respectability, while at the same time representing the tempting new freedoms of the city, where an expanding economy of consumable goods available to everyone was eroding older social boundaries.

Framing all these acts of urban looking was the gaze of the art-going public, those critics, collectors, and audiences who consumed these paintings of modern life and, in doing so, made art into an activity only one step removed from voyeurism. Linking the aesthetic gaze to commerce, motivated by consumption and desire, the Ashcan painters joined a long line of later artists who worked on the borderline between art and the everyday.

Hairdresser's Window (fig. 12.5), also by Sloan, shows a young woman, probably one such working girl, her face turned tantalizingly away as her long red hair ( a familiar marker of Irish ethnicity) is parted and colored by a buxom woman of coarse features and conspicuously dyed blonde hair. We can only guess what her new color will be; the freedom to choose, however, is also the freedom to disguise her social and ethnic identity. Such disguise provoked growing anxiety from the mid-nineteenth century forward, playing on older fears about the social fluidity of life in the nation's cities. Sloan's painting, however, goes one step further by revealing-indeed putting on display- the mechanics of such deception by which one thing disguised itself as another: Irish working-girl as fashionable woman. The use of hair dye and cosmetics was frowned upon, especially by those struggling to preserve older standards of feminine behavior from the taint of the "new woman." Sloan flaunts the ways in which the ethnic and working class cultures of lower Manhattan joyously intermingled public and private spaces. The painting is full of his humorous asides to his audience (the hairdresser, in a French pun, is "Malcomb"). At street level are passersby, ranging from the heavily made-up woman on the far left a streetwalker, perhaps-to the animated shop girls who respond to the spectacle with giddy laughter, and the workingman, pipe in mouth, and bowler-hatted gawkers hoping to catch a glimpse of the mysterious beauty. From the window scene of hair-dyeing to the manikin heads in the storefront below, and the signs advertising gowns, the scene proceeds seamlessly toward the crowded streets, connecting the socially mixed urban population to new habits of dress and appearance. Privacy was a privilege of middle-class life not afforded by the crowded streets of lower Manhattan. Yet, Sloan implies, there is a certain enjoyment to be taken from the spectacle of the city, framed as a window within a window. The framed image of the hairdresser becomes yet another commercial sign advertising goods and services for sale.

Like others in the Ashcan group, Sloan embraced the democratic, leveling effects of the twentieth-century urban environment, even as he allowed middle-class audiences to view the scene through window-like openings and stage-like spaces that maintained a safe social distance. Differences in codes of dress and behavior also helped middle-class viewers maintain their moral and social grounding as they savored the heady and liberating environment of the new city.

ETHNIC CARICATURE. Visual markers of ethnic difference helped preserve the social boundaries between middle-class audiences and the immigrant and ethnic subjects of the Ashcan painters. Motivated by a democratic vision explored in the poetry of Walt Whitman beginning in the 1850s, the paintings and graphic images of the Ashcan group took in all classes and ethnic types in the new city. Despite this inclusiveness, however, Ashcan artists still shared a strong impulse to organize the social variety of the urban environment through ethnic typing.

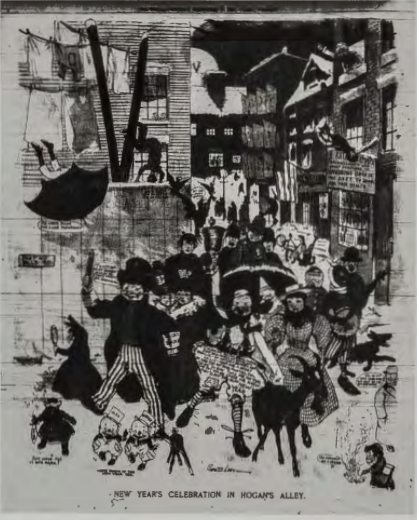

Their graphic training as visual journalists encouraged forms of shorthand that bordered on caricature, as visual and social typing blurred into stereotype. George Luks (1866-1933) began his career as a sketch-reporter and a cartoonist; his New Year's Celebration in Hogan's Alley Sunday comic (fig. 12.6) featured a motley array of urban ethnic and social types. These ranged from young Irish street toughs to banjo-strumming "darkies," to Englishmen, Cossacks, and middle-class female settlement house workers, in a joyously boisterous parade through the tenements. Contained within the borders of the immigrant ghetto, such subjects were unthreatening, offering easy humor of the sort that was mostly excluded from the high art medium of painting.

Luks's Hester Street (fig. 12.7) is a more sober view of this dense immigrant neighborhood in lower Manhattan, marked by subtly observed class and social distinctions among individuals within the mass.

In other images, however, boundaries disappear in a vision of the city as a melting pot. In William Glackens's (1870-1938) Washington Square (fig. 12.8), the viewer encounters children tormenting one another, old women dozing, respectable matrons with their children, nannies, top-hatted gentlemen, and street toughs, in an apparently untroubled if chaotic setting. Glackens grabs the eye with cartoon-like vignettes; with its high horizon line, Washington Square offers an exuberant panorama of a democratic culture where everyone has a place. In paintings, prints, and comics, the urban realists spanned a range of responses to the emerging pluralism of the new American city-from parading ethnic difference to celebrating a common civic culture of shared public spaces, as first envisioned in Frederick Law Olmsted's Central Park (see fig. 8.7).

GENDER AND THE ASHCAN ARTISTS. Despite the democratic inclusiveness of Ashcan rhetoric, their insistence on the virile individualism of the male artist implicitly excluded women. Abastenia St. Leger Eberle (1878-1942) shared subject matter with the Ashcan artists, but a different attitude is evident in her sculptural work. The male artists of the Ashcan group kept their distance from their ethnic subjects. They also rarely allowed overt political topics to intrude into their paintings, retaining the traditional distinction between fine art and graphic media. Influenced by the settlement movement of Jane Addams, in which reformers took up residence among the immigrant poor, Eberle made her studio in New York's Lower East Side. In her bronze sculpture You Dare Touch My Child (fig. 12.9) she pushes the urban realist encounter with the audience one step further. Eberle's subject is a scrawny woman of haggard features holding a screaming child, and raising her fist in anger toward an unseen antagonist. Her stance transforms the viewer from voyeur into engaged participant.

In its militant subject matter and implied struggle against anonymous forces threatening the mother- child bond, the work closely resembles the political lithographs of The Masses (see below). By choosing to depict maternal rage in the face of an unseen threat, Eberle also revealed a feminist understanding of how women's experience as mothers could be mobilized for political action.

Graphic Satire in The Masses

Much of the work by the Ashcan artists bordered on the satirical. This impulse, however, was restrained by the fine art medium in which they worked. Graphic arts traditions and print media-unlike fine art-allowed greater room for narrative condensation, caricature, and caustic satire. Radical politics and satire came together in the graphic art of The Masses, a periodical magazine whose contributors included John Sloan and George Bellows. Beginning publication in 1911, The Masses expressed social and political critique with a new graphic language: abbreviated, rough, bitingly humorous, keenly responsive to the contradictions of society and to the daily violations of hallowed ideals. As writer, activist, and editor Max Eastman put it, "We would give anything for a good laugh except our principles."3 Devoted to a form of home-grown socialism, The Masses remained in circulation until 1917, when it was shut down by the U.S. Postal Service for its opposition to America's entry into World War I. The targets of its satire extended from the idle rich to militarism, corporate greed, the hypocrisy of organized religion, and the corruption of the mass media by big business. Rebecca Zurier has identified the significance of the graphic style developed at The Masses, where a rough crayon line came to convey "a graphic tradition of social protest," breaking with the suave manner of such mainstream illustrators as Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944).4 Visually condensed, and accompanied by captions or titles steeped in irony, the best of this work expressed complex ideas in simple terms. In Boardman Robinson's (1876- 1952) haunting image, Europe 1916 (fig. 12.10), a shrouded figure rides an emaciated donkey ·in pursuit of a carrot on a stick labeled "Victory;" and held over a precipice. In the tersest possible terms, the image conveys the futility of World War I. The graphic work of The Masses also heralded a new internationalism; alongside everyday images of New :York working girls and laboring men were works critical of the nationalistic fervor that fueled World War I.

As its statement of purpose proclaimed, The Masses was owned by those who made and produced it; with admirable consistency, it remained accountable only to its principles. "Printing what is too Naked or True for a Moneymaking Press," its policy was "to do as it Pleases and Conciliate Nobody."5 The editorial independence of The Masses proved crucial to its freedom of expression, especially in an era that witnessed growing media consolidation and corporate control.

The Social Documentary Vision: Lewis Hine

Along with Jacob Riis (1849- 1914; see Chapter 11), though a generation later, Lewis Hine (1874- 1940) stands at the beginning of the photographic documentary tradition that takes as its subject the working poor and the socially marginalized. Their documentary work overlaps with that of urban realist painters in the opening years of the twentieth century. Riis's subjects display the physical marks of the "slum"; they reach us through the language of difference, conveyed by their squalid surroundings. The Ashcan artists, by contrast, were drawn to the animated spectacle of street life, and rarely focused on the individual in favor of social types increasingly familiar to audiences through their portrayals in films, cartoons, and prints. Hine's objective, however, differed fundamentally from both Riis and the Ashcan School. Sponsored by the National Child Labor Committee, part of a broader Progressive reform movement during the first two decades of the century, Hine documented children working in order to call attention to their difficult work conditions. He often smuggled his camera into facto- ,ries to avoid detection. Progressive reform attempted to work within the existing two-party system of government to address a wide range of issues facing American cities as they struggled to accommodate the massive influx of new arrivals. The reform movement's policy issues included child welfare, regulation of industry; workers' compensation, and the overhaul of corrupt urban machine politics.

At its best, documentary endowed images with the power to motivate social change. Supported by social statistics- a new practice derived from the emerging field of social science-Hine's photographs brought to light the poverty and exploitation of those living beyond the confines of middle-class experience. His close framing and direct approach brought his viewers into an intimate encounter with the subjects of his photographs. His pioneering work led directly to federal legislation prohibiting child labor, passed in 1916. With its power to bring previously hidden social conditions to light, documentary photography became the first step toward social action to improve lives. Riis's photographs produced the effect of a sudden and shocking revelation; Hine's were thoughtfully framed and drew on a familiar cultural imagery of mothers and children, childhood innocence, and stoic dignity in the face of hardship.

In recent years, the tradition of social documentary has been criticized by historians for exploiting its human subjects and denying their individuality and power to make constructive change in their own lives; it has been accused of rendering its subjects passive in the face of overwhelming problems. Hine's contribution to the documentary tradition contradicts this view. The human subjects of his photographs retain their individual identities; their worlds remain continuous with ours. Whether poor tenement dwellers in the Lower East Side, steelworkers in Pittsburgh, or immigrants from Russia and Eastern Europe facing an uncertain future in Ellis Island, Hine's subjects reveal a range of response to life usually effaced by the abstractions of social science. Early on, Hine's mentor at the Ethical Culture School urged him to photograph the immigrants at Ellis Island with the same regard as he would give "the pilgrims who landed at Plymouth Rock."6 Here were the faces of the "huddled masses yearning to breathe free," in the words of the American poet Emma Lazarus (1849-87) in her sonnet "The New Colossus" (1883), inscribed on the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty.

Hine's respect for his subjects produced images of individuals struggling to maintain human connection and domestic order amidst impossible conditions. His camera surveyed a range of moods, from childish delight to curiosity, boredom, watchfulness, mischievous fun, moral and physical exhaustion, and despair. There is, in his collective work, no single "image of the slum," or of the immigrant working classes, only a range of individuals facing the difficult challenge of starting over in a strange new land. Hine emphasized not the markers of difference (poverty, sordid surroundings, physical brutalization) but the bonds of common humanity uniting Americans across class and ethnic lines. Little Mother in the Steel District, Pittsburgh (fig. 12.11) is remarkable for its intent focus on the physical bond between the young girl, still a child, and her brother. This girl-woman, whose long hair cascades down her back, holds a real baby instead of a doll; both seem unconscious of the presence of the camera, caught in a moment of mutual affection, touch, and budding curiosity about the world beyond the self. Self-sufficiency supplants desperation: we are engaged, not through pity but through empathetic connection.