11.3: Reasserting Cultural Authority

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Augustus Saint-Gaudens' Adams Memorial commemorated a deeply private loss (see p. 356). But Saint-Gaudens also made numerous public monuments that would be widely emulated in memorial sculpture in the next generation. Among his most visible is that to William Tecumseh Sherman (fig. 11.17), the general who turned the tide of the Civil War in a destructive southern campaign most remembered for the burning of Atlanta. Though originally intended by Saint-Gaudens for a site within Central Park, the monument is now situated across from the Plaza Hotel at the corner of Central Park South and Fifth Avenue where, regilded, it has become a familiar landmark. Saint-Gaudens combined a powerful naturalism-in the figure of Sherman himself, with his weathered face and billowing cape-with the Renaissance language of allegory, as he had in his memorial to Robert Gould Shaw (see fig. 9.6). Leading the general on horseback is a winged angel of victory, wearing a Greek peplos that flutters out behind her. She wears a laurel wreath signifying fame and clutches a palm branch of peace. The massive stone Renaissance plinth of the memorial, designed once again by his friend the architect Stanford White, provides a fitting support for the figural group, which combines lifelike animation with a sense of Renaissance terribilita., the avenging moral and physical force of the conqueror. The equestrian monument advances south, in the same direction as traffic on Fifth Avenue, a triumphal allusion to resolute leadership. The Sherman Monument carries viewers well beyond New York: recalling the grand equestrian portraits of Europe, it summons the nation to honor valor. General Sherman offered an example of the ruthless courage required of the empire that America was becoming, in the decade that saw the bloody Spanish American War (1898) culminating in the transfer of the Philippines from Spain to the United States, the forced annexation of the autonomous islands of Hawai'i (1893- 1900), and the internal conquest and confinement of Plains Indian cultures. In keeping with such imperial ambitions, the Sherman memorial exemplifies a reassertion in the 1890s of older forms of cultural authority.

Together Saint-Gaudens and Stanford White epitomize the ''American Renaissance" (a phrase first used in 1880), a bold and confident movement spanning the arts of sculpture, painting, architecture, and decorative arts that was grounded in the authoritative use of monumental forms drawn from the past.

Financed by public funds and the huge industrial fortunes made during the post-war period, the great public edifices of this period- libraries, men's clubs, government buildings, railroad stations, museums, opera houses, monuments, and exposition halls- turned to classical art and architecture. Classical allegory and architectural forms were heralded as a shared cultural language safely above the fluctuating sphere of the personal and the subjective. Artists of the American Renaissance saw themselves as carriers of tradition, drawing upon the finest models of the past to open a new era of cultural polish for a young nation long derided as provincial and crassly materialistic. In addition, the American Renaissance signaled a shift away from predominantly rural, agrarian, and individualistic values to the urban and cosmopolitan identity that characterized much of post-war American culture. "Now," wrote the art critic William Brownell in 1881, "we are beginning to paint as other people paint."8 What distinguished the American Renaissance was the authoritative role held by the classical tradition. Those who spoke on its behalf denounced the qualities that Symbolist artists in these same years embraced-personal expressiveness and the cultivation of a private vision-in favor of historical precedent. Classical forms carried the message of cultural hierarchy and control (both architectural and social), and the magnificence of the classical tradition lent weight and authority to the numerous new public institutions that were taking form.

The Universal Language of Art

A leading exponent of the American Renaissance was Kenyon Cox (1856-1919), a painter, muralist, and outspoken defender of artistic precedent as a guide to the present. The Classic Point of View (1911) was his declaration of the enduring significance of craftsmanship and technique, the reliance on artistic models, and the continuity between past and present. Turning away from the struggle to define a peculiar American identity in the arts, Cox embraced the nation's European heritage. Unlike the next generation of modernists, against whom he loudly declaimed, the academicians believed that cultural authority rested in history: the classical language "asks of a work, not that it shall be novel or effective, but that it shall be fine and noble. It seeks not merely to express individuality or emotion .... It strives for the essential rather than the accidental, the eternal rather than the momentary-loves impersonality more than personality."9 The academic viewpoint submerged the personality and idiosyncrasy of the artist in public symbols. Accordingly, academic public art couched its appeal to universal values in allegorical figures, invested with symbolic meaning-Truth, Justice, Art, History, and so forth as in Elihu Vedder's Rome or The Art Idea (1894), painted for Bowdoin College in Maine (fig. 11.18).

Claims to universality, however, made sense only among those who assumed that the classical tradition was the measure against which all other cultural achievements were to be judged. In fact, as a visual language, allegory was remote from everyday experience, referring to a Greek and Roman heritage far removed from the working people and immigrants who were the intended audience for its message of cultural uplift and timeless truth.

Monumental Architecture in the Age of American Empire

From Boston to New York to Cleveland and San Francisco, the ideals of the American Renaissance are still visible in a legacy of monumental civic architecture and urban design. The leading architectural firm associated with the American Renaissance was the New York-based McKim, Mead, and White. The firm completed over 300 commissions in New York between 1879 and 1910. Pennsylvania Station (fig. 11.19) served as an imposing gateway into New York City for travelers arriving by train. Combining the grand stone-vaulted spaces of imperial Rome (fig. 11.20) with the modern construction methods of cast iron in the train sheds, Penn Station gave the new era of train travel a grandiose aspect. The General Waiting Room rivaled St. Peter's in scale, and was touted as the largest single room in the world. With its integrated program of waiting rooms, commercial arcades, concourses, and dining areas, Penn Station achieved a new combination of practicality and architectural sophistication. Its destruction in 1963 following a long fight to save it was a tremendous loss to the nation's architectural heritage.

An ''.American" renaissance implied a comparison with the princely and civic patronage that fostered the Italian "rebirth" of classical culture in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In parallel fashion, the new American civic landscape, with its message of cultural order and historical authority directed at the urban masses, was supported by the fortunes of those fueling industrial expansion: Andrew Carnegie (who endowed libraries), Henry Clay Frick, J. Pierpont Morgan (who bought manuscripts), John D. Rockefeller, the Astor and Whitney families, and Henry Villard. The buildings recalled Renaissance palazzi and other familiar historical forms: hemispheric domes and majestically vaulted spaces, classical facades, painted and sculpted female figures, and axial planning of both architectural interiors and of the city as a whole.

In architectural terms, the American Renaissance sought to do away with the chaotic styles of previous decades. As with other Paris-trained architects of the postwar years, the architects of the American Renaissance sought a new visual unity and design discipline, attuned to modern requirements and functions. But unlike Richardson and Sullivan, they practiced an archaeologically precise emulation of the past.

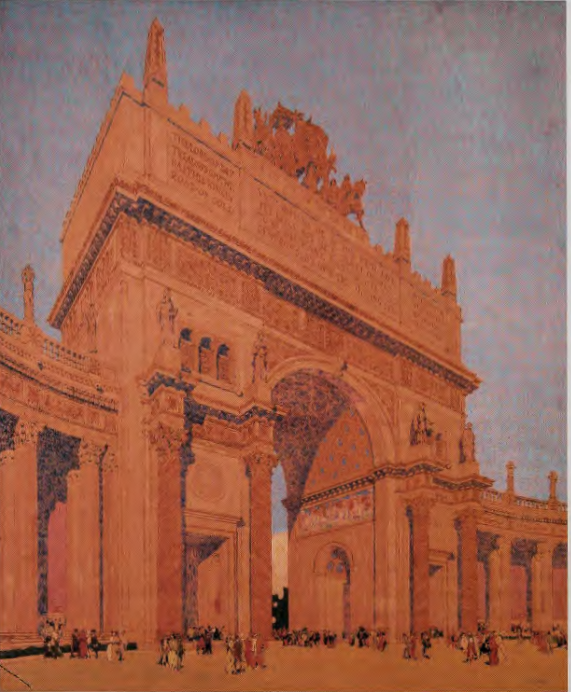

The American Renaissance gave a cultural and artistic shape to America's emerging imperial identity- its rise to a new military, industrial, and commercial dominance in both the Atlantic and Pacific arenas. Stanford White's (1853-1906) triumphal Arch of the Rising Sun from the Court of the Universe (fig. 11.21), done for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in 1915, employs the form of the triumphal arch associated with the Roman Empire. Such arches appeared frequently in these imperial decades: commemorating America's past wars, celebrating its imperial present, and celebrating military victories such as that of Admiral Dewey over Spain. White's arch includes a double colonnade inspired by Bernini's design for the piazza in front of St. Peter's in Rome. In place of the quadriga of the victor (a charioteer driving four horses) that traditionally adorns the top of triumphal arches, White has, somewhat whimsically, placed an oriental retinue, complete with bejeweled Indian elephant. Here, White's arch announces the hopes of extending America's trade empire to Asia, at the edge of the Pacific Rim in San Francisco, the culmination of the westward course of empire, the fabled "passage to India" that realized the dream of unity between East and West. In the 1890s and early 1900s that dream carried both democratic possibilities and imperial ambitions. America, heir of the ages, was a new Rome, borrowing older forms to project an image of a rising empire.

The American Renaissance was full of impulses that seem contradictory to us today: objectifying women through the repeated use of the female nude as allegory, the movement.also supported artistic training for women; taking a stand against artistic individualism, it nonetheless fostered a range of impressively creative talents; exercising elite control over culture, it also contributed to the establishment of numerous new art institutions-from the Society of American Artists to the American Academy in Rome-that would collectively revitalize American art training. Despite its hierarchical and elitist orientation, the American Renaissance promoted public monuments such as the Statue of Liberty and later the Lincoln Memorial that have come to symbolize the dream of an inclusive, yet ethnically and socially diverse democracy.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS. The Library of Congress exemplifies the American Renaissance's impulse toward incorporation and unity. The Reading Room expresses this quest for centralized control of knowledge. Circular in form, it is loosely based-like Jefferson's Library at the University of Virginia (see fig. 5.16)-on the Roman Pantheon, symbol of the known world. The Library of Congress aspired to be a democratic version of the great libraries of the Old World, such as the ancient library at Alexandria, or the vast imperial and papal collections that contained Europe's cultural heritage. A hemicycle mural on the ceiling allegorized the four continents; the cultures of East and West-Asia, Europe, and the New World; and the Greco-Roman and Christian cultural inheritances from the past (fig. 11.22). The accumulated knowledge of the ages is the subject matter of mosaics, murals, sculpture, and stained glass throughout the Library. Assisting in the management of this world of knowledge was the Dewey decimal system, invented by an American librarian (Melvil Dewey) in 1876-a new method for classifying, cataloguing, and archiving knowledge. Such cataloguing systems were just one aspect of the managerial efficiency that increasingly characterized the administration of learning, scientific expertise, and governmental control in these years. But while centralizing knowledge, the Library of Congress also democratized it by allowing the public access to the vast archive of history and information it contained, in a manner that anticipated the internet today.

THE COLUMBIAN EXPOSITION IN CHICAGO, 1893. The fullest realization of the American Renaissance quest for unity and centralized control was the Chicago World's Fair, or Columbian Exposition, of 1893. Ironically, this vision of cultural stability and permanence was itself a mirage, a plaster and lathe concoction of historical forms, supported by an iron armature. The centerpiece was the Court of Honor (fig. 11.23), a dazzling stage set evoking the grand empires of the Old World. Dubbed "the White City," it rose in a few short months along the shores of Lake Michigan. Daniel Burnham (1846- 1912), based in Chicago, led a team of designers-"the greatest meeting of artists since the fifteenth century!" as Augustus Saint-Gaudens proclaimed. 10 They established a uniform cornice line and imposed a strict axial arrangement of space throughout the central zone. At the center of the Court of Honor was a huge reflecting pool presided over by Daniel Chester French's (1850- 1931) monumental allegory of the Republic. Rigidly frontal, its archaic form projected the discipline and strength befitting a muscular young empire, while recalling the ancient Greek origins of the American nation-state. This monumental tribute to the classical world differed vastly from the modest virtues of the Greek Revival in the early part of the century.

Around the court were arranged the exhibition buildings: Machinery, Electricity, Mines and Mining, Liberal Arts, and Agriculture, the nodes of America's emerging industrial infrastructure. The figure of Christopher Columbus presided over the fair; his role in "discovering" the New World gained symbolic importance in the context of the "world-making" discoveries in science and industry displayed there.

With its lagoon, classical buildings, and public statuary, the Court of Honor bore more than a passing resemblance to the central canvas of Thomas Cole's The Course of Empire (see fig. 8.19). Yet the architects of the fair-unlike Cole half a century earlier- now embraced the analogy with imperial Rome rather than taking it as a stern warning. This shift in identity from republic to empire was in keeping with the imperial ambitions of the times. Revealing the distance between image and reality, however, was the real city of Chicago, just beyond the boundaries of the fair, reeking of industry and stockyards, its commercial landscape blackened by urban grime, its architecture a chaos of different styles.

As the historian Henry Adams- a visitor at the fair-- wrote years later, the Chicago Exposition "was the first expression of American thought as a unity." This "unity," however, was not merely formal and architectural, but ideological. It organized the history and cultures of the world around a single measure that ranked social and cultural development according to race. The ideology of the fair misapplied the theory of evolution to a descending scale of "civilization," with the white European at the top, followed by the cultures of Asia, Africa, and the New World Indian.

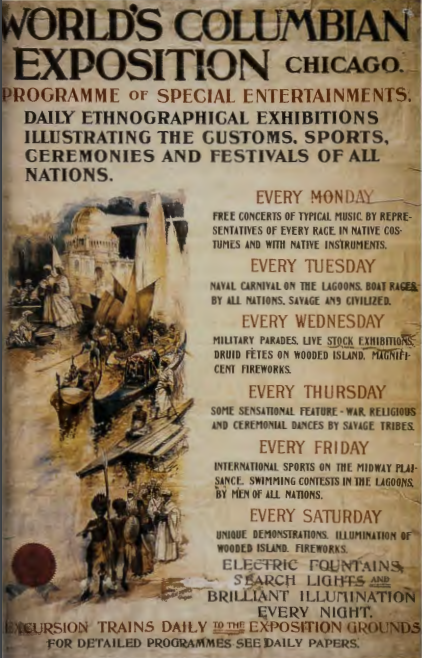

One of many posters celebrating the fair as both education and entertainment (fig. 11.24) exposes its object lessons as well as its contradictions. At the top of the image is Richard Morris Hunt's Administration Building, at the head of the Court of Honor, its beam of light illuminating a parade of nations. This parade ends in a troupe of African Bushmen located furthest from the white Administration Building (but closest to us) and equipped with spears and shields. The poster presents the world's cultures as both objectified and available for the entertainment of fairgoers. While reaffirming the "object lesson" of imperial order, the visual economy of the fair was propelled by the market-based relations between Americans and the world in which all things appear as consumable commodities.

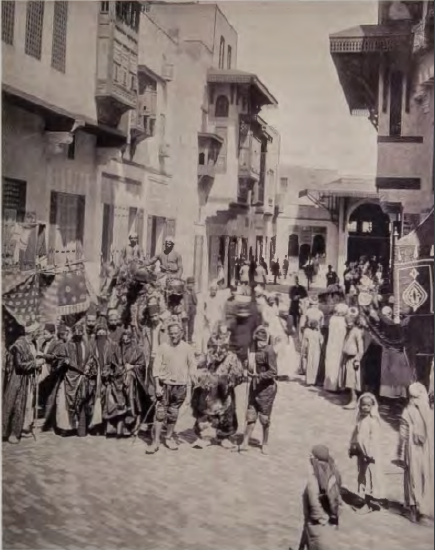

Virtually every exhibit in the fair projected the lesson of cultural superiority and imperial condescension. Ethnological exhibits equated the non-Western societies on the peripheries of empire with the "primitive" origins of the human race as well as with the developmental phase of childhood. Barring the participation of African Americans as anything other than measures of cultural inferiority, the fair gave a scientific gloss to segregationist ideology. The dream of cultural perfection- of light, order, and global harmony- was grounded in a hierarchy embodied in the layout of the fair itself, moving from the glistening white and rigidly formal Court of Honor to the more park-like "Wooded Isle," containing the Women's Building and the Japanese exhibits-both proximate to the white European male. Beyond these "wooded isles" was the Midway Plaisance (fig. 11.25), a 'living museum of humanity," opening with German and Irish villages and "descending" to Asian, North American Indian, and African.11 In a carnival zone, bearded ladies, sword swallowers, and belly dancers appeared alongside naked Bushmen and Southwest Pueblo Indians in mock authentic settings. In the Midway, the pleasures of the body took over; visitors could relax while maintaining a safe distance from the "lower orders" of humanity. The thrilling sensations of the Ferris Wheel, which was making its first appearance, and the gyrations of the infamous belly dancer "Little Egypt," who made strong men go weak at the knees, offered an escape from bourgeois constraints. The formal discipline of the Court of Honor gave way to serpentine footpaths and uncensored experience. Visitors gawked and roamed freely in search of new sensations, participating in a new consumer culture of pleasure and impulse. The Midway anticipated the popular entertainments that took center stage in the twentieth century and undermined from within the racial and cultural hierarchies that were still so crucial to the thinking of American elites at the end of the nineteenth.