11.2: Feminine/Masculine- Gender and Late-Nineteenth Century Arts

- Page ID

- 232331

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The 1890s was a time of rigid gender definition. Saint-Gaudens's refusal to make the shrouded figure in his Memorial to Clover Adams (see p. 356) identifiably male or female was a rarity. Since the early nineteenth century, the ideology of separate but complementary spheres for men and women had been an organizing principle of American social and cultural life. As industry displaced artisanal production, and work moved out of the home, the distinction between public (male) and priv.ne (female) worlds widened over the course of the century. According to this ideology, men's talents lay in the public realm of business and politics, industry and technology; men were the agents of social progress, of artistic, scientific, and intellectual advance. Women, by contrast, were destined by their natures for the private realm of home and family (see fig. 6.1); they were the element that stabilized society through their selfless devotion to aesthetic and spiritual ideals, cultivation of beauty and emotion, and moral elevation- in short, "the higher life." The ideology of separate spheres, complementary and unequal, while elevating women as the "angels" of the household, and as morally refining "procreative" influences, also denied them the power of original creation. Women's role was to reproduce the cultural order. Throughout the repeated shocks of modernization, clearly defined gender roles offered reassurance that the basic arrangements of social life were stable.

Yet the cultural organization of gender difference was increasingly out of step with women's demands for greater self-determination. Middle-class women began to enter the public sphere through the social reform movements of the antebellum era-such as suffrage and abolition. Intensified female participation in the civic sphere during the Civil War demonstrated the power that alliances of women could exert on the moral and social fabric of the nation decades before the Nineteenth Amendment (1920), which gave the vote to women. After the war, growing numbers of women wanted an active part in the cultural, social, and professional worlds of the nation, flocking to universities and newly opened colleges for women, such as Vassar ( est. 1865) and Bryn Mawr (est. 1885), as well as art academies and professional schools.

However, female assertiveness provoked a multilayered reaction directed at containing women's claims for public recognition on the same terms as men. While women by the 1890s had gained some recognition of their rights to education, and to professional and creative lives outside their roles as wives and mothers, they faced a range of obstacles beyond institutional barriers.

In late-nineteenth-century society, the nonproductive realms of consumption, aesthetics, and refined perception were considered feminine . Despite a growing presence in the public sphere, women were still symbolically linked to the domestic realm and to private life, and were thought to have a kind of interiority, or subjective life, suited to the appreciation of art. But this did not mean women were to be accepted as artists; on the contrary, the attributes of an original artist-a pronounced individuality, a 'bold" or daring execution, and focused mental power- were thought to belong uniquely to men. According to this thinking, the qualities that made women good consumers, mothers, and wives-susceptibility and intuition-made them unsuited to creative endeavors- to anything but minor, imitative art. To paint like a man was damning praise, implying that a woman had desexed herself. Narrowly defined by their reproductive function and by their biological rhythms, women who aspired to be taken seriously as artists were accused of betraying their own natures. And their natures denied them artistic genius, which was exclusively associated with male individuality.

Women's attempts at creativity automatically gave rise to assessments that subtly demeaned their efforts while reinforcing men's status as the producers of culture. This gendering of aesthetic worth, as scholar Sarah Burns has pointed out, linked artistic skill to expertise, dispassionate scientific vision, and analytic force. In these decades, style carried deeply gendered meanings for both female and male artists. Men as much as women were defined by these aesthetic discourses, even as they produced them. A more bureaucratic and technologically driven work world compromised men's sense of autonomy in the workplace and control over their professional lives, producing new forms of gender anxiety. Themes of athleticism, intellectuality, and confrontation with nature in the artworks of Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer reflect these masculine preoccupations. Such works bear witness both to the defining role of gender in late-nineteenth-century culture, and to the efforts of art to give dimensionality and breadth to gendered selfhood.

Women Artists and Professionalization

From the late eighteenth century on, artistic women had been consigned to amateur status by their lack of academic training, and their links with such "minor" media as watercolor. Women were also valued as copyists of the Old Masters; lacking in creative ego-so this thinking went- they transmitted the spirit of the male artist in all its unsullied purity. Women's marginalization within the art world resulted in part from lack of access to the institutions of training and the time to devote themselves to art. Nevertheless, between 1870 and 1890 the number of professional women artists increased from 414 to 11,000, according to the U.S. Census. Academic training now allowed them to master the technical requirements for making art; European study and travel put the great inheritance of past art within reach; force of numbers created supportive communities of women artists as alternatives to the social networks, clubs, and student I teacher bonding that helped male artists along the path of success. Women students in Paris submitted works to the French Salon in growing numbers, testing themselves in the most challenging arenas of male artistic professionalism.

A WOMAN ARTIST'S SELF-PORTRAIT. One such aspiring artist in Paris was Ellen Day Hale (1855-1940), who submitted a self-portrait entitled Lady with a Fan (Self Portrait) (fig. 11.8) to the Paris Salon in 1885. Turned sideways in her chair, she confronts the viewer directly, a slight challenge suggested by her upturned chin. While she holds a black feather fan-an emblem of coquetry-she has painted herself with the look and attitude of a young boy, although she was thirty-five at the time. Refusing to veil her individuality or artistic ambition, Hale uses her self-portrait to demonstrate her familiarity with the latest and most sophisticated languages of art. Her confident self-presentation is set against an aesthetic organization of abstract colors and shapes. In the very act of painting a self-portrait, she lays claim to her right to be an artist.

Hale's self-portrait reveals a sense of energy and professional self-regard in which the woman appears as an actor in the art world rather than as a passive consumer, decoratively posed in the studio of a male artist, as in figure rn-4 by William Merritt Chase. Her androgynous self-presentation resists the gender typing that confined women within prescribed boundaries, even as it subtly reconfirms the association between the feminine and the decorative.

Men Painting Women; Women Painting Themselves

At the same time that women were exerting their presence as active creators of art, they entered American art in another manner: as the object of aesthetic interest among male painters. Indeed women, as scholar Griselda Pollock points out, were "the continual subject of much of what we consider modern painting."6 The growing difference between male and female spheres of action led, in turn, to increasing differences in the ways that men and women were represented. Women had appeared frequently in antebellum art; with rare exceptions, however, they were depicted as marginal figures in a social landscape of mixed company, often spanning generations and including servants. While a crucial element in the domestic economy of antebellum America, women in genre painting nonetheless remain onlookers in a world that belonged largely to men. In the post-war years, however, the figure of the middle-class woman, often minding children, gave way to a new subject: the elegantly dressed woman of leisure, usually alone, and situated in a beautifully arranged interior where she does nothing in particular. Why the sudden prevalence of this highly staged and artificial subject?

As American society became increasingly defined along class lines, clear demarcations of social status acquired greater importance. This new subject matter served to assert the superiority of the upper classes, who considered themselves to be the custodians of beauty and refinement, while simultaneously idealizing restrictive roles for women. Leisure and self-cultivation were luxuries afforded only by the privileged; the upper-class home was to serve as a showcase of luxury and refined taste.

GETTING TOGETHER FOR TEA. In William Paxton's Tea Leaves (fig. 11.9), two well-dressed women have tea in an elegant interior. A Chinese table, Japanese screen, embroidered shawls, blue Delftware, and Colonial silver suggest the accoutrements of an upper-class Boston milieu with its taste for antiques and its aestheticism. One woman leans back in her chair to contemplate the contents of her tea cup, with the suggestion that they hold the answer to life's most difficult problems. Yet her desultory attitude suggests too much time on her hands; she appears slightly bored. Much painting of the so-called "Boston School," flourishing from the 1870s until well into the twentieth century, drew inspiration from the Dutch interiors of Jan Vermeer, where women pause in a charged atmosphere of radiant quiet. Ignoring the social issues of the day, such as ethnic immigration, labor militancy, and the movement for women's rights, the paintings of the Boston School escape instead into a world of exquisite confinement. Stylistically conservative, the Boston School painters situated the privileges of culture and wealth at a safe remove from social realities. The male who enables such privileges is absent. Instead, feminine leisure, aesthetic taste, and careful orchestration of decor symbolize the prestige of the unseen male head of household who makes it all possible.

THE LIFE OF LEISURE. Musical themes, in which women in aesthetic dress strum long-necked antique instruments or pluck keys on a harpsichord, suggest both the rarefied environments of wealth and leisure and the interweaving tonal harmonies of color and sound. In Thomas Wilmer Dewing's (1851-1938) Brocart de Venise (Venetian Brocade) (fig. 11.10 ), the woman closest to the viewer seems transported to another world by the music of a harpsichord, an eighteenth-century instrument whose rarity was symbolically linked to the attenuated beauty of the woman herself. In these works, women appear not as social subjects but as aesthetic objects in an artistic composition, paradoxically protected from the public sphere yet on view as symbols of refinement and culture. This strict separation of public and private, cultural refinement and social realities, was termed the Genteel Tradition by philosopher George Santayana in 1911.

THE FEMALE EXPERIENCE. Women artists confirmed, but also expanded, and occasionally subverted received ideas about their proper sphere. Mary Cassatt's family wealth afforded her the privilege of setting up a household in Paris where she could enjoy great personal independence (her parents and sister soon joined her). At the same time, Cassatt (1844-1926) was unable to paint the cafe-concerts, the bars, the brothels, races, and the backstage theatrical scenes that distinguished the work of Manet and Degas-such places were off-limits to a respectable single woman. Instead, Cassatt chose to paint the public, and, later, the domestic, lives of women-as mothers, sisters, and members of privileged social networks with which she had intimate familiarity. In a series of works set in public spaces, Cassatt painted young upper-class women shyly presenting themselves to the gaze of the public as they emerge into consciousness of their femininity. These works transmute the familiar theme of the female on display for the male gaze by portraying the female experience instead; rather than mere objects of desire and aesthetic control, Cassatt's women seem fully alive, responsive, and psychologically complex. And in one instance, In The Loge (fig. 11.11), the woman is the one who looks, training her opera glasses on the stage. Dressed in the black proper for older bourgeois (or prosperous upper-middle-class) women in public, she is intent on observing the world around her. In the background, from the other side of the loge, an older man in evening dress directs his opera glass at the woman in a knowing commentary on the frequency of the theme of men looking at women. Here, however, the woman assumes an active stance, leaning forward with confidence as she claims the privilege of looking openly, a curious, fully present subject rather than an object of another's gaze.

Although Cassatt actively supported the emerging feminist movement that transformed opportunities for women in the twentieth century, she did not wish to be considered first and foremost as a "woman artist." Cassatt transformed the restrictions on the lives of bourgeois women into the enabling conditions of her art. She developed her own formal language-admired by her Impressionist contemporaries-out of the spaces of urban bourgeois femininity: the theater, the domestic parlor, the public garden, and the nursery. She used these settings to forward her aims and gave to her female subjects a sense of interior life that drew them beyond the realm of spectacle and fashion to which conventional art so often consigned them. She made women the subject rather than the object of art.

THE ARTIFICE OF FEMININE BEHAVIOR. Cassatt's much-admired Philadelphia contemporary, Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942), also transformed the subject of women from objects of enigma, beauty, and mystery to female subjects with intelligence and assertiveness. Beaux's Dorothea and Francesca (fig. 11.12) combines portrait and genre elements in an understated image of the two young daughters of close friends. Beaux's painting begins and ends with a specific moment in which femininity is performed. Their heads bowed and hands clasped, the two girls are intensely absorbed in the act of learning. The smaller girl points her foot tentatively forward, as if feeling the ground, while her older, more confident sister instructs her through example. Everything, from the angle of their heads to the subtle cues of posture, suggests the artifice of feminine behavior. Yet here we also sense that, in the intense concentration and inward focus of the two girls, there remainswithin these learned roles-room for personal growth and self-expression.

Beaux's painting reflects on her own life. Remaining single, she achieved an international reputation, exhibiting in Paris, New York, and Philadelphia, and was hailed toward the end of her life by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt as "the American woman who had made the greatest contribution to the culture of the world."7 She learned and practiced the codes of feminine behavior well enough to defuse the threat of a style that male critics identified as "masculine" in its assurance and vigor. Unlike Cassatt, Beaux was opposed to women's suffrage, and convinced that most women were happiest in domestic roles. She compared her own creative urge to the maternal act of birthing. Yet like Cassatt, she refused identification as a "woman" artist, even as she honored conventional notions of femininity in her personal life. Freedom to live in a wider world, Beaux's career suggests, was earned, for this generation, through the successful performance of femininity.

Thomas Eakins: Restoring the (Male) Self

Gender is a social rather than a biological category. It is a way of thinking about the effects of culture on the body. No American painter of the late nineteenth century pursued issues of gender more relentlessly than Thomas Eakins (1844- 1916). As a young man, Eakins had combined drawing classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts with anatomy instruction at the local medical school. While a student in Paris, he had boycotted the classes of his teacher Jean-Leon Gerome on days when the class drew from antique casts. Later, as a teacher, Eakins insisted instead on drawing from live figures, producing animated charcoal sketches on those occasions when a model posed for the class.

MECHANIZATION SETS THE TERMS. Eakins viewed the male body through the lens of industrial production, as an efficiently calibrated machine. When painting women, on the other hand, he highlighted their inner worlds of thought, consciousness, and feeling. In Eakins's early works, men are often portrayed in the midst of athletic activities outdoors. Women appear almost exclusively in interior settings. The two worlds meet only when Eakins brings his men indoors, portraying them as professionals surrounded by the tools of their trade.

Eakins's treatment of men coincides with what literary critic Mark Seltzer has termed the "machine culture" of the late nineteenth century. Over time, human labor would come to be measured by the standards of productivity and efficiency that were associated with machines. While some of Eakins's contemporaries would celebrate the body-as-machine, Eakins came to feel entrapped by it. In the early 1870s, Eakins painted images of scullers boating on Philadelphia's Schuylkill River. Sculling was regarded as a "scientific" sport. One of many leisure activities that developed as a form of middle-class relaxation- an antidote to the rigors of industrialization- sculling nonetheless required machine-like technique, self-discipline, and mental concentration. For men in particular, athletic events like sculling offered an opportunity to reassert their control over their environment, after toiling all week within what was often a depersonalized work space. The bright skies, crystalline air, and stilled spaces of Eakins's The Champion Single Sculls, 1871 (formerly known as Max Schmitt in a Single Scull) (fig. 11.13), evokes a world of calmness and repose. But the scene also contains an undercurrent of anxiety, as if, in the words of Henry David Thoreau, men have become the "tools of their tools."

The painting contrasts the leisure activities of its two scullers, gliding across the Schuylkill River on a crisp October day, with the signs of industrial work, signaled by the smallish puffs of white smoke in the background. The figure in the foreground, Max Schmitt, turns to look at the viewer as his scull drifts into the left foreground. In the background is Thomas Eakins, who has signed his name across the hull of his boat. Behind the scullers we see Philadelphia's Railroad Connection Bridge and the Girard Avenue Bridge, over which a train enters on the right. Together these signify the forces of industrial production. They contrast not only with the natural world of clouds and sky, but with the more human world of the painting's two scullers, whose success depends on discipline and bodily strength rather than steam and technology. Eakins's scullers are thoroughgoing professionals, men who dominate their worlds through intellectual and bodily exertion. By inserting himself into the picture, Eakins identifies his activities with those of Schmitt. As art historian Martin Berger has argued, Eakins links his skills as a painter with Schmitt's prowess as an athlete. In the process, Eakins converts painting from a socially marginalized-and potentially feminized-occupation into a masculine and professional endeavor.

Yet The Champion Single Sculls converts leisurely activity into another form of industrial discipline. Though the scullers take command of their watery world, they do so only by internalizing the efficiency, concentration, and mental control that govern their behavior in the work world. We see this tension between work and leisure in the striking way that Eakins portrays both Schmitt and himself, each figure rising perpendicularly against the lateral sweep of the Schuylkill River. That uprightness stands as a sign of their mastery over their environment. It is the most human element in the painting. And yet each figure is also enclosed by a visual parallelogram formed by the two oars and their reflection in the water. This compositional diamond claps the scullers in a grid that arrests their motion and diminishes each man when measured against the Schuylkill's broad expanse. Are the men masters of their environment or trapped within it? Are they in control of the body-machine, or extensions of it? Although The Champion Single Sculls offers no clear answer to these questions, it tells us, by its juxtaposition of scullers with trains and steamboats, that we cannot understand the former except in the language provided by the latter. The world of steam, iron, and mechanization, though confined to the background, nonetheless sets the terms for the figures in the foreground.

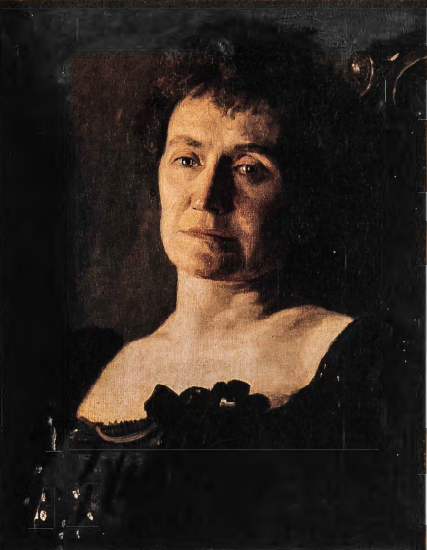

LIFE OF THE MIND, LIFE OF THE BODY. If Eakins's men inhabit a realm that is hard, disciplined, and machinelike, then Eakins's women dwell in a domain of thought, feeling, and self-reflexiveness: a . rich inner life unfazed by technology. The split between the two reflects a larger division in Eakins's life between mind and body, grounded in the conditions of labor in the late nineteenth century. Portrait of Mrs. Edith Mahon (fig. n.14) appears to brood on feelings or memories that the viewer can only imagine. The mood of the painting is somber. The brown background, dark dress, and black ribbon extend spatially the sad and intense emotions that define Mahon's face. Her eyes are moist, and her chin and cheeks are ruddy. Her mouth slants downward in a slight frown, sealed as tightly as the emotions she seems to hold in. Eakins has aged Mahon, who was an accomplished pianist in Philadelphia. He often portrayed his women sitters as older than they were, burdening them with an awareness of time and loss. Mahon later confided to a friend that she was unhappy with the portrait but accepted it as a favor to Eakins, whose paintings were often uncommissioned. Eakins wrote on the back of the canvas: "To My Friend Edith Mahon/ Thomas Eakins 1904."

Art historian David Lubin has suggested that Eakins's portrait offers a pointed contrast to the tradition of male figures shown in public positions. The painting highlights emotion rather than civic action, and captures feelings that are fleeting and fragile rather than the timeless and classical expressions associated with men's public roles. Edith Mahon also anticipates early cinema's experiments with close-up shots as a way of visualizing a character's inner states. The portrait embodies precisely what is missing from the world of Eakins's athlete heroes.

In 1875, Eakins turned a canvas of rowing studies over on its back and started sketching a portrait of Dr. Samuel Gross, a well-known Philadelphia surgeon. The Clinic of Doctor Samuel Gross (The Gross Clinic) (1875) portrays Gross in a surgical amphitheater operating on a patient for osteomyelitis, in which the femur bone becomes infected, and for which the treatment had been amputation of the limb (fig. 11.15). Gross stands to the left of the operating table. He is assisted by five physicians, one of whom sits behind Gross and is visible only by his hands. To Cross's side, at the canvas's bottom left, the patient's mother turns her head away from the procedure. She shields her eyes with her fisted left hand. Seated next to the amphitheater entrance at the far right of the canvas, barely visible in the shadows, Eakins includes himself, observing the operation with a pencil and pad.

The painting was originally designed to hang in the art exhibition section of the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. But the Centennial art jury found The Gross Clinic too distasteful. The prominent exposure of the patient's thigh and buttock, together with the bright red blood covering Grass's fingers and scalpel, left the jury feeling that The Gross Clinic was unfit for a mixed audience of men and women. Its realism seemed all too real. For Victorian viewers, the painting lacked elevating moral content. The Gross Clinic was displayed instead in the medical section of the Centennial Exposition, the first in a series of controversial decisions that would dog Eakins's life. One decade later, Eakins would be expelled from his teaching position at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts for removing the loincloth from a male model in a drawing class attended by both men and women.

Eakins's commitment to realism was more than a question of style or aesthetics. Realism represented a commitment to scientific investigation and to a worldview grounded in natural laws. It stood opposed to sentimentalism or any other approach that valued emotion and feelings above dispassionate rational inquiry. When Eakins insisted that his students at the Pennsylvania Academy study anatomy from cadavers, he did so because he believed that every painter needed to understand the human body as precisely as possible. Artists, for Eakins, were professionals, and like all professionals, they needed to view the world with full knowledge and intellectual objectivity.

Realism was also tied to questions of gender. We see this in the relation of the distraught mother in The Gross Clinic to the surgeons-all male-engaged in the operation. By making the mother the bearer of emotion in the painting, Eakins contrasts her smallish figure with the upright and commanding presence of Dr. Gross. Her hysteria contrasts with his rationality. Her presence also alludes to the professionalization of medicine after the Civil War, when physicians and surgeons began to form their own associations. They established professional codes of behavior to distinguish their activities from those of the female world of amateur healers. As with architects, doctors now possessed the power to accredit new members, prescribe standards of conduct, and oversee the education of those entering the profession (the role occupied by Dr. Gross as he instructs an amphitheater full of medical students).

The blood on Grass's hand and scalpel signals Eakins's refusal to allow his art to be compromised by Victorian notions of propriety. Eakins just as deliberately affronted the sensibilities of his nineteenth-century viewers by portraying the buttocks and anus of the patient. Scholar Michael Fried has interpreted the blood-red scalpel as an allusion to the artist's brush and palette knife, the dripping vermilion of the blood echoing the pigment on the painter's brush. Eakins, in effect, transforms Gross into an artist-figure, a stand-in for Eakins himself. In so doing, he links painting to surgery as he had earlier linked painting and sculling. In each case, the common bond is the display of discipline and mastery that distinguishes scullers, surgeons, and painters as modern professionals.

Dr. Grass's bloodied hand also calls attention to the essential unity of intellectual and manual labor. Eakins highlights Grass's forehead with an intense white that counterpoints the red of the scalpel. Gross is defined visually by the relation of these two compositional foci: head and hand. Like John Singleton Copley's Portrait of Paul Revere a century earlier (see fig. 4.32), Eakins's portrayal of Dr. Gross emphasizes the intellectual mastery that guides the surgeon's-or silversmith's-hand. The figure of the professional embodies a unity of mind and body that predates the modern division of labor. In The Gross Clinic Eakins counters the effects of modernization not by retreating from them, but by transforming the newly modern professional into a figure who restores precisely what has been lost with the advent of corporate society. The Gross Clinic uses modernity against itself by rendering the professional an heroic figure.

PORTRAIT OF FRANK HAMILTON CUSHING: CROSSING CULTURES. By the late nineteenth century, the battle between Native and white for control of the frontier was largely over. With the surrender of Geronimo to the U. S. Army in 1886 and the Wounded Knee Massacre (1890), the Plains Indian Wars came to an end. European Americans had reshaped the West in their own image. The terms of encounter now included a new figure: the anthropologist. Anthropology developed in the nineteenth century as a profession devoted to the study of so-called "primitive" societies, those occupying the lowest rung on the ladder leading from savagery to civilization. But with proper tutelage, they could rise to a higher state. Anthropology in these years employed an absolute (Western) standard of measure by which non-Western cultures were judged and found wanting.

In 1895, Thomas Eakins painted a portrait of an anthropologist who worked against the grain of his profession (fig. 11.16). Frank Hamilton Cushing, employed by the Smithsonian Institution, was the first person to use the word "culture" in the plural: "cultures." Cushing refused to believe that Western society represented the highest form of evolution, employing instead a relative measure of value. For Cushing, non-Western traditions, rituals, customs, languages, and complex forms of social organization, though different from those of the West, were not inferior. To the contrary, Cushing found that Native societies of the Southwest, in particular the Zuni, provided forms of spiritual and cultural wholeness lacking in European and American life.

Cushing earned both fame and derision for his decision to become a member of the Zuni. Originally sent in 1879 by the Smithsonian Institution on a two-month factfinding and collecting tour, Cushing decided to become a full-fledged member of the tribe instead. He stayed for four and a half years, mastering Zuni language and customs, joining the Bow Priesthood, and rising to the position of First Chief Warrior. He was finally recalled to Washington after participating in a Zuni raid on a Navajo encampment, arguing for Zuni ownership of a disputed land claim, and signing his official correspondence with the Smithsonian "1st War Chief of Zuni, U.S. Asst. Ethnologist." Cushing had become a man of two worlds.

In order to paint Cushing's portrait, Eakins first converted a corner of his studio into a space resembling a Zuni kiva. The full-length portrait frames Cushing between a ladder on the right (for entering the kiva) and a large spear with dangling feathers on the left. In the lower right of the portrait, a small altar holds a Zuni bowl. A fire burns below it. According to a student of Eakins, the fire was lit in the studio in order to reproduce the smoky atmosphere of an actual kiva. A war shield with an image of the Zuni war god hangs from the wall on the left, below a pair of antlers.

Cushing posed for the portrait in the costume that he routinely wore while at Zuni. It is anything but authentic. Rather than dress in the white cotton blouse and baggy trousers that members of the Bow Priesthood wore during sacred ceremonies, Cushing invented his own, highly picturesque version of Indian dress. He wears a dark blue shirt embroidered in bright colors at the shoulders. His buckskin belt threads through large silver circles hammered from silver dollars. The buckskin trousers feature a line of silver buttons running down the side. Two red sashes on the leggings complement the red scarves around his neck. Cushing wraps a dark blue sash around his head and wears silver and turquoise earrings.

Cushing's lean and ravaged face contrasts with his clothing and paraphernalia. He holds a Zuni war club in his right hand and a prayer plume in his left. The strap dangling behind his right leg was used to whip mules and horses. Yet the face suggests a man of introspection. The heavy lines and pockmarks age Cushing far beyond his thirty-eight years. His portrait, painted exactly two decades after The Gross Clinic, taps into Eakins's lifelong desire to capture on canvas the professional world of scientists, scholars, and teachers whom he admired. But whereas Gross and others painted by Eakins embraced modern life, Cushing took the opposite tack. He attempted to enter a different, premodern world, maintaining an identity grounded in two worlds simultaneously.

Eakins's portrait presents a man who imagined himself as the "soul of an Indian of olden times." At the same time, Eakins frames Cushing with objects larger than he is (the ladder and spear), and contrasts the full roundness of the war shield in the background with the sharp angles and emaciated face of someone whose thoughts seem to be reaching back to a world that survives only through its relics.

The portrait is a meditation on the Western relation to the cultural other. Cushing's act of cross-dressing is more than "playing Indian." By recreating his kiva world in Eakins's studio, Cushing attempts to reclaim a former identity; his costume is an effort at rejuvenation that his downcast gaze suggests can never really happen. What Eakins's portrait captures is Cushing's need to feel Indian. At the same time as the West dominated Native peoples economically and militarily, it also turned to those it conquered for spiritual solace and renewal. Eakins's painting captures both the power of that nostalgia and the profundity of introspective loss when faced with its futility.

Eakins's portrait of Cushing contrasts strongly with the self-portrait of Kiowa artist Wohaw, "Wohaw Between Two Worlds," painted at almost the same time as Cushing's residence among the Zuni (see fig. 9.37). Cushing voluntarily reached out to Zuni culture for a sense of wholeness and masculinity that he found lacking in Western society. Wohaw, on the other hand, came to understand Western culture through his experience as a prisoner of the United States. What both men share is the awareness that their lives have changed through contact with another culture: Wohaw can look calmly toward Western culture because he is grounded in Kiowa customs. Cushing's world is a personal creation, surviving only in his mind and his artifacts. There is no make-believe for Wohaw. There is instead the reality of conquest, and the need to navigate two worlds in order to survive.