7.3: Native Arts of Alaska

- Page ID

- 232312

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Native arts of Alaska, like those of other regions previously examined, reveal the global reach of culture, almost from the moment of first encounter. Native people came into contact with foreign explorers in the late eighteenth century. By the nineteenth, some grew wealthy from their exchanges with British and American fur traders. While coastal Alaska may seem remote from the cosmopolitan cities of Europe and eastern North America, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries it was a crossroads of cultures, a meeting place of Native, Russian, Spanish, British, and American economic interests from the previous century. In addition, traders, whalers, explorers, military men, and missionaries pursued diverse ambitions in the territory. Their impact on Native cultures was dramatic. Some Native individuals and communities prospered through participation in the international fur trade; others were almost wiped out by smallpox, influenza, and other diseases. Some groups became mutual trading partners, while in other cases coercion and bloodshed ruled. Alaskan arts embodied these cultural changes, as Native cultures seamlessly integrated such external influences into their social needs and ceremonial life, and as imported goods became fundamental to clothing, sculpture, and the ritual of gift exchange, for example. The non-Native arts that we compare to Native ones are small portable objects made by whalers rather than broadly appealing images directed at a national audience.

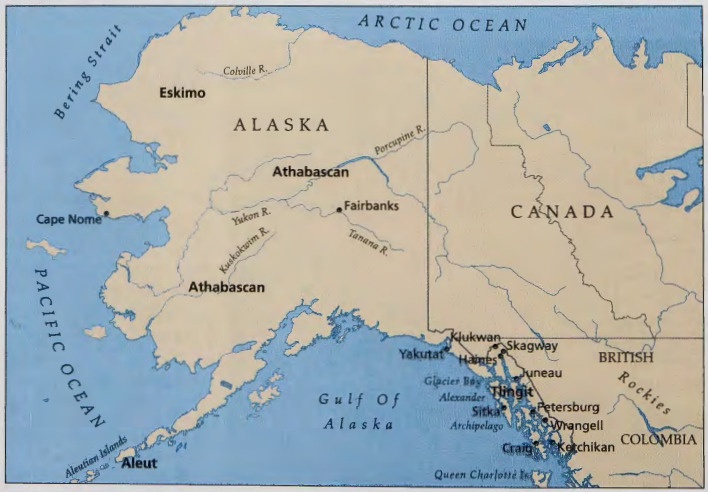

The indigenous inhabitants of what is now Alaska include Eskimos and related Aleut peoples of the northern and western coast and the Aleutian Islands, northern Athabaskan peoples of the interior, and Tlingit in the southeast Alaska panhandle (see map, fig. 7.21). Eskimo cultures share a great deal with Siberian and Canadian Eskimos.

(In Canada, they are called Inuit, though in Alaska, Eskimoan people prefer the more specific cultural designations of Yupik or Inupiaq.) The Tlingit are the northernmost extension of Northwest Coast Native culture. Their art and social systems are most closely related to the Haida and other indigenous peoples of the coastal province of British Columbia in Canada.

From Vitus Bering's first voyage in 1741 to its purchase by the United States in 1867, Alaska was claimed by Russia. Seeking to make their fortunes, the Russians were principally interested in seal and sea otter pelts to sell in China. The Russian-American Company, a trading concern chartered by the tsar in 1799, was the most prominent organization. Russian nobility and government officials held shares in it, but its business went well beyond the world of commerce. It was authorized to explore and colonize, in the hopes that the northwest coast of North America would become an income-producing area of the Russian empire. By the end of the eighteenth century, Russian traders (followed by Russian Orthodox missionaries) had settled the Aleutian Islands and the panhandle of Alaska; they even maintained a fort in northern California. Following the Russians, Americans changed the face of Alaska through exploration, mining, settlement, and tourism. The historic arts of this region reflect its cultural hybridity. Indigenous technologies were put to foreign use. Foreign materials and tools irrevocably changed Native arts. New markets opened for Native artists as well.

Tlingit Art: Wealth and Patronage on the Northwest Coast

The visual realm of the Tlingit people provides a remarkable example of how art can function as currency in a system of social status, self-display, and family prestige. The Tlingit have lived in the panhandle region of Alaska for several thousand years, and have used for well over a thousand the distinctive pictorial style they share with their Haida and Tsimshian neighbors in Canada.

Though Tlingit art is made principally from local materials such as cedar, it has long been involved in an international exchange of ideas and materials. Before the coming of Europeans in the eighteenth century, the Tlingit traded with Eskimos to the north for walrus ivory, with Athabaskan peoples in the interior for animal hides embellished with bird quill decoration, and with neighboring Northwest Coast groups.

In the late eighteenth century, Russian, Spanish, and British explorers sailed into the harbors near Tlingit villages. Russians established a fort in their territory in 1799 and settled there until the U.S. purchase of Alaska (though the Tlingit claimed that the $7,200,000 should have been paid to them, rather than the Russian interlopers).

In the early to mid-nineteenth century, the Tlingit grew wealthy from their exchanges with British and American fur traders. The outpouring of art made during this period is a reflection of that prosperity. Traditional culture was highly stratified, from chiefs of important clans and their close relatives downwards. Art works commissioned for chiefly feasts and give-away ceremonies, known as "potlatches," displayed family crests and emblems. In Northwest Coast belief, Raven, Whale, Wolf, Bear, and other animal heroes interacted with ancestors in the distant past, and that relationship formed the basis for social status, embodied in artistic imagery.

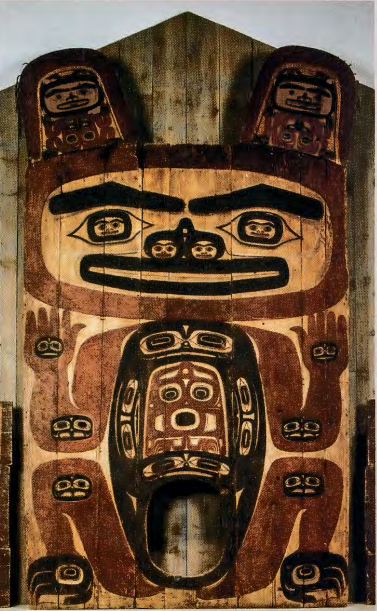

THE WHALE HOUSE OF THE RAVEN CLAN. An 1895 photo of the interior of the Whale House depicts how family wealth was displayed, not only in the architecture itself, but in the other possessions belonging to the high-ranking members of this family (fig. 7.22). Ambitiously carved and painted screens covered with heraldic designs were often erected on the rear platforms of houses. The most famous of these, called the Rain Screen, was installed in the Whale House in the village of Klukwan, perhaps at the very beginning of the nineteenth century. The painted, low-relief carving probably depicts Raven, the Northwest Coast culture hero, who stole water from another bird in order to given humankind the fresh water (in the form of rain, rivers, and lakes) needed for communal survival. The huge eyes of Raven can be seen directly behind the figures wearing ceremonial garb and standing on the top step of the platform. Above, a series of smaller, seated figures represents the personified raindrops that splashed from Raven's beak as he flew over the world with his precious cargo of water.

Carved posts on either side of the screen stand adjacent to posts that support the beams of the house. They are embellished with human and animal figures, stacked in totem pole fashion. These figures depict characters in myth and clan history that relate to the founding of certain family lines. Unlike some of their Northwest Coast neighbors, the Tlingit did not carve tall, outdoor totem poles until late in the nineteenth century. Instead, they carved structural elements in the large communal houses, such as the screen and house posts here. They also carved masks, headdresses, and storage boxes, much like those displayed on the platform steps.

By the time this photograph was taken in 1895, the Tlingit had been trading with and living near European people for over a century. They wore tailored shirts and trousers, as is evident in the photograph, but they continued to make and use traditional carvings and regalia, and value the objects made by their forebears; much of the clan wealth displayed here was already several generations old.

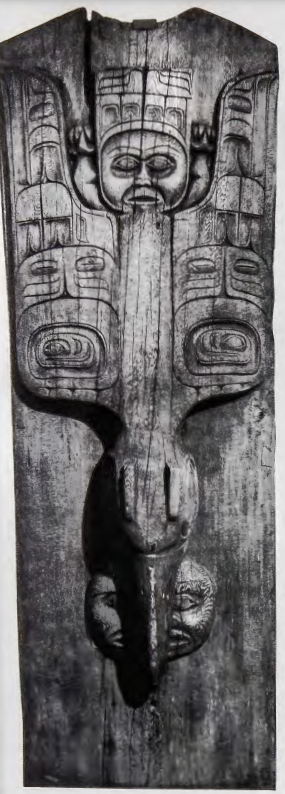

RAVEN AND THE SUN. A house post from Taquan village shows the elegance of nineteenth-century Tlingit carving (fig. 7.23). The post depicts a downward-facing Raven clasping the sun in its beak. Its wings and tail feathers are ornamented with formlines and ovoids (see below), the building blocks of Northwest Coast imagery. While it would originally have been painted in traditional colors of black, red, and blue-green, the many peeling layers of overpainting were eventually removed, the better to reveal the delicacy of the carving. The raven's head stands out from the surface of the post in high relief, while the body, wings, legs, and tail feathers are carved in much lower relief.

Both this house post and the headdress frontlet (fig. 7.24) have as their subject Raven and the Sun. A famous myth recalls that in ancient times a greedy chief kept daylight hidden in a box in his house, causing the creatures of the world to live in gloomy twilight. But the meddling hero, Raven, snatched the box in his strong claws, and flew out of the chief's house to give sunlight to the whole world. In figure 7.24, Raven holds the precious box. (In contrast, in the house post, Raven carries the fiery globe in his beak.) The outside of the box is inlaid with a sparkling mirror fragment. Another mirror sits in the orb above Raven's head, like a miniature sun. Oral history handed down with this object, which dates from around 1850, tells that the mirror, a treasured heirloom, was acquired from the first white man known to the people of this village.

Folded into the quintessential Northwest Coast story of Raven and daylight is a tale of intercultural encounter, as expressed in the materials that make up the object. Raven effortlessly incorporates materials from diverse parts of the world: in addition to the imported mirror, on the back of the headdress (not illustrated here) is a woven band of flicker tail feathers, probably made by Native people of California, and the shiny abalone shell in Raven's teeth, nostrils, eyes, and ears also came from that region.

Formlines and Ovoids: The Building Blocks of Northwest Coast Design

ART OF THE NORTHERN Northwest Coast is immediately recognizable because of its graphic design system, shared by the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian peoples. Worked out by artists centuries ago, and still in use today, this system is built of formlines, ovoids, and split U-forms. A formline is a connecting contoured line which structures the design and generally outlines human or animal anatomy. An ovoid is a slightly rectangular oval shape (usually with a hint of an upward bulge at its base) which delineates eyes, feathers, joints, and other points of emphasis. Feather-like U-forms often fill both formlines and ovoids in a harmonious way. The carver would trace formlines on the wood, either freehand or using a stencil, before he began to use his adze.

An artist could use formlines and ovoids in a simple manner, to make a graphic image easily legible (see fig. 7.28, Grizzly Bear screen) or in a complex manner, to make the images almost disappear in an elegant welter of shapes decipherable only by another master artist.

TRADE GOODS. Here, as elsewhere in Native North America, imported goods were significant components of the visual vocabulary. For a period of about fifty years starting around 1780, Northwest Coast Indians traded sea otter pelts to British and American ship captains, who exchanged metal, guns, cloth, food, and exotic goods for these valuable furs, much prized in China. Ships leaving Boston harbor would sail around South America, up to the Pacific Northwest, across to Hawaii, and then on to Canton in China where they would exchange the furs for tea, fine porcelains, and silks. They often realized a profit of between 200 and 600 percent for their efforts. This Pacific trade brought large quantities of manufactured goods into Native hands. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, one sea otter pelt could be exchanged for five muskets, or six yards of cloth, or sturdy wool blankets, or a collection of kettles, knives, combs, buttons, and beads. Much of this new material found its way into Northwest Coast art.

The importance of cosmopolitan materials, and the ingenious uses to which they could be put in order to reinforce traditional beliefs, are demonstrated in another mask (fig. 7.25). A hook-nosed eagle spirit with inlaid shell teeth has large round eye sockets containing Chinese coins as eyes. In ceremonial dances, conducted in the flickering firelight of a large clan house, the shiny metal eyes, pearly teeth, and real hair of such a mask would give a life-like aura to the spirit represented by the dancer, while the exotic eyes perhaps hinted at the spirit's connection with, or power in, distant worlds.

In some cases, imported materials and tools were refashioned into statements of local ethnic identity. The British blunderbuss, a relatively short gun with a wide muzzle (fig. 7.26), was surely obtained in exchange with a British trader. The Tlingit artist personalized it by carving low-relief formline and ovoid designs of a wolf into the walnut stock. Such imprinting of cultural symbols onto foreign objects recalls the hybrid images from the first centuries of encounter on the East coast (see figs. 2.14 and 2.16, war club and pipe tomahawk). Here, even the thunder-discharging guns of the white men have been taken into the universe of local objects.

The 1904 photograph of a potlatch in Sitka, Alaska (fig. 7.27), is an encyclopedia of the trade among European, Asian, and Native societies. Trade goods were creatively transformed to produce an impressive display of wealth and cosmopolitanism. In addition to locally carved headdresses and basketry caps, the high-ranking clan members in this photo wear tailored ermine jackets modeled after Russian sea captains' coats, locally woven robes, and cloaks constructed from imported wool blankets festooned with buttons. Beaded bags and bibs attest to trade with inland Athabaskan Indians.

For male artists on the Northwest Coast in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, trade with Euro-Americans made a profound difference in the way they practiced their arts. New tools of iron were a marked improvement on indigenous carving tools of stone and bone, allowing them to carve on a grander scale and with greater ease and rapidity. For female artists, it was not innovative tools that revolutionized their arts; it was an entirely new vocabulary of materials. Considering the length of time it took to spin, dye, and weave an intricate blanket, it is not surprising that women adopted woven trade cloth, embellished it with beads and buttons, and made new ceremonial garments. The earliest European and American visitors to the Northwest Coast all report that wool blankets, beads, and buttons were highly valued trade items, as the potlatch photograph indicates.

The great British maritime explorer Captain James Cook (in his 1778 voyage from Hawaii and up the west coast of North America), and the Russians who sailed across the Bering Strait and down the coast of Alaska, were among the first to bring beads and cloth to the Northwest Coast. These clothing items were so rapidly assimilated into Native life that only fourteen years after Cook's voyage another sea captain observed that one chief's family arrived at a banquet all dressed in English woolens. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Hudson's Bay Company wool blanket had become a unit of currency. Rich individuals accumulated hundreds of them, and at ceremonial potlatches scores of blankets were given away as gifts.

THE CONCEPT OF AT.ÓOW. All of the artworks illustrated here were used in status-conferring rituals, feasts, and theatrical displays. Central to understanding Tlingit art is the concept of at.óow (status, meaning, and power derived through ownership). Art objects, names, stories, and other things both tangible and intangible can accrue at.óow when they are displayed, sung, danced, or recounted in public ritual witnessed by other people. Objects, names, and songs can be handed down from generation to generation, accruing more meaning, value, history, and prestige with each generation. This system connects past generations with those to come, and links the human community to the spiritual one.

Tlingit Art, Ownership, and Meaning Across the Generations

TLINGIT POET AND SCHOLAR Nora Dauenhauer has described her culture's art in Western museums as "like a movie without a soundtrack," for without the animating force of oratory and the public acknowledgment of rights, an art object is essentially meaningless, according to Tlingit worldview. Western museums may contain objects that are recognized by the Tlingit as still being the property of particular clans, or of individuals. For example, for more than fifty years the Denver I Art Museum has "owned" a painted architectural screen from the Grizzly Bear Clan House at Wrangell, Alaska (fig. 7.28). The Grizzly Bear is the most. important crest of the Shakes family, whose chiefs go back countless generations. Although the screen itself is in a museum, the crest image is owned by Chief Shakes, in a system akin to a Western system of copyright. The Denver screen, dating from the mid-nineteenth century, probably replicates an even earlier house screen. In the 1930s, the Denver screen served as the model for a new community house dedicated to the seventh Chief Shakes, Charley Jones, who assumed his hereditary title when this building was dedicated in 1940. (For further discussion, see fig. 16.18: CCC photo of restoration of Chief Shakes house.)

In Northwest Coast culture, replacements are routinely commissioned for worn-out heirlooms; what an individual holds inalienably is the right to own, display, and replicate certain enduring family emblems. Oral history relates that in ancient times the bear accompanied Shakes ancestors as they scaled a mountain to escape a flood; since that time they have owned the rights to the bear emblems. In an early-twentieth century photograph of a modern Chief Shakes house (see fig. 9.44), European-style architecture (with wooden clapboards, glass windows, and hinged door) provides the setting for Chief Shakes Vi's totem poles (George Shakes, who served as chief from c. 1876 to 1916). One pole depicts a human figure wearing a Killer Whale crest hat; the other depicts the Grizzly Bear of the clan's founding legend. On the pole are the footprints of the bear as it scaled the mountain with the Shakes family's ancestors. Tradition exists seamlessly with modern "improvements."

Aleut, Yupik, and lnupiaq Arts: Hunters and Needleworkers

During the decades when frontiersmen and Indians encountered each other in the trans-Mississippian West, and the Tlingit were trading with the Russian Navy and New England whalers, the Native peoples living further north in coastal Alaska had their own interactions with foreigners, some of whom came to depend on the skills of indigenous hunters and seamstresses in order to survive the bitter northern weather.

A WATERPROOF GARMENT OF SEAL INTESTINE. Skin and hide clothing is fundamental to survival in the Arctic. Without the warmth of several layers of animal skins to combat the prolonged sub-zero temperatures of an Arctic winter, there would have been no Eskimo civilization. From the shores of the Bering Strait in Alaska, across northern Canada, and into Greenland, Eskimo bands have survived for thousands of years through the skill of male hunters and female clothing specialists. Above the treeline in the tundra, there were no other materials for garments. There was no weaving, except for isolated instances of grass-reed basket weaving. People relied on caribou, walrus, and seal for food, clothing, and shelter. In addition to the well-known fur parka, Eskimo and Aleut women made a distinctive waterproof parka that men wore over their fur garments while hunting in icy waters. These parkas were made of gutskin-the dense, inner layer of walrus, sea lion, or seal intestine. When butchering the sea mammal, women would clean and scrape its many yards of intestine and cut them into long strips. Sewing the strips together with thread of animal sinew made the garments waterproof, for sinew expands when moistened, making watertight seams.

Whalers and explorers found that they could learn much from local people about survival in the Arctic winter, quickly recognizing the superiority of Native garments over their own. They commissioned women to make them parkas like those worn by indigenous people, but the newcomers also readily accepted a new garment that Aleut women designed, modeled on the eighteenth-century Russian Navy officer's greatcoat. A wool greatcoat was exceedingly heavy when wet, but a gutskin cape or greatcoat weighing just a few ounces would effectively protect a man on the deck of a ship from rain and salt spray.

This marvelous transcultural garment (fig. 7.29) represents the marriage of the finest indigenous technology with a recognized European clothing style to make an item of use and beauty that was widely traded. The Russian-American Company purchased them for their crews. Under the auspices of this business, thousands of sea mammals were slaughtered for their fur, which was shipped to Russia and China and made fortunes for these maritime entrepreneurs. Through the ingenious artistry of Aleut seamstresses, the intestines from these animals kept the traders dry while they plied northern waters. Virtually every greatcoat surviving in a museum collection demonstrates that these women were not simply making a utilitarian garment for a market. All the examples are embellished with tufts of fur or cloth, bands of bird quill designs, and other ornamental flourishes.

lntercultural Arts in Nome, Alaska, circa 1900

WHILE ESKIMO ARTISTS have been carving ivory for more than two thousand years, some of the best-known works date from the decades around 1900, when new markets opened for these craftsmen as a result of the Alaskan gold strikes of the 1890s. Gold was discovered on Cape Nome in 1899, and the next two years witnessed a stampede to the tiny hamlet of Nome; in 1900 alone twenty thousand hopeful prospectors left ports on the West Coast and headed there. It quickly became a boomtown of prospectors, speculators, and businessmen, and a trading center for local Eskimos. So the arts in early-twentieth-century Alaska underwent yet other changes, as their audience expanded to include greater numbers of white residents and tourists.

An lnupiaq man named Angokwazhuk (1870-1918) arrived in 1900. He had come from a distinguished hunting family, but an accident on the sea ice left him partially lame. At the age of twenty-two, he signed on with a whaling ship as a cabin boy, and there he observed the art of scrimshaw. In Angokwazhuk's capable hands, the whalers' technique of incising scenes on ivory and darkening the incisions with graphite or ink merged with his own native heritage of ivory carving. In Nome, he carved full-time , and successfully sold his incised cribbage boards and other ivory items. Widely recognized as the finest carver in Nome, Angokwazhuk could also incise pictures on a walrus tusk with near-photographic precision. He often copied photographs or advertising images, producing portraits of President Woodrow Wilson, local businessmen and tourists, and even a self-portrait. He occasionally signed his work "Happy Jack," the English nickname given to him by the white inhabitants of Nome because of his disposition.

In one engraved tusk (fig. 7.30), Angokwazhuk has drawn a life-like portrait of an orthodox Jewish couple. A Hebrew inscription reads "May you be inscribed for a good year 5671 " , (i.e. 1910). A commission for the Jewish New Year in 1910, the tusk contains a gold nugget in the shape of a Star of David, and the inscription "Nome, Alaska." This unusual tourist item (perhaps a gift from one of Nome's Jewish merchants for long-separated relatives elsewhere in the country) stands as a testimony to the intercultural commerce and art in the far north at the beginning of the twentieth century.

A HUNTING VISOR. In the sea-mammal hunting cultures of northern and western Alaska, much of ceremonial life was devoted to placating the spirits of these animals. The traditional belief (still maintained today) is that animals have souls, and the job of the human community is to honor the souls of animals captured in the hunt. Aleut and Yupik sea-mammal hunters wore bentwood visors to shade their eyes from the sun's glare (fig. 7.31). But the aesthetic and symbolic aspects of these visors were even more important than the practical ones. Hunters adorned themselves in elegant ways as a sign of respect for the animals that allowed themselves to be hunted. Such adornments narrated previous success in the hunt and pleased the animal spirits. Aleutian visors were elaborately painted, while Yupik carvers embellished their visors with ivory amulets decorated with abstract as well as figural designs. A group of three-dimensional walrus heads is fastened to the middle of the visor illustrated here. These are flanked by abstract loon heads, for the loon is a great hunting bird, diving into the sea to snag its prey. The loon beaks are incised with scenes of hunting for bear and caribou.

BENDING WOOD AND BONE. Yupik and Aleut hunter/ carvers used ingenious steaming technology to make these hats. We know from archaeological excavations that this method of steaming wood and bone into curved shapes dates from ancient times. In one of many acts of crosscultural artistic exchange, Native artists learned about pictorial imagery from the printed materials and photographs the whalers carried (see Intercultural Arts, below), while New England whalers learned the skills of ivory carving and bentwood technology from Eskimo men hired to work on board their ships. The New Englander Horace Young, who made the box in figure 7.32 around 1850, almost certainly learned the unusual craft of splitting and steaming whalebone from an Eskimo expert in the north Pacific on one of his four voyages on a whaling ship. He made the box for his wife back home, who used it to store coffee (yet another product of a maritime cultural encounter). Ivory from whale teeth is inlaid in a sunburst and star pattern on the lid of the box. The piece of steamed whalebone from which the box is made is cleverly joined: Young fashioned hands- a right hand for the lid and two left hands for the container itself-as if the box holds its precious contents tight.

While we do not know if Young made other such objects, he was one of many nineteenth-century whalers who, to pass the long days at sea, took up the art of scrimshaw. Some of these men, like Young, made unusual vernacular objects such as this one as a keepsake of their travels in distant waters.