7.2: Living Traditions and Icons of Defeat

- Page ID

- 232311

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Indian Removal policies set in place by Andrew Jackson, president from 1828 to 1836-culminating in the notorious ethnic cleansing of settled agrarian Cherokee people from Georgia (the 1838 "Trail of Tears")-forced Native groups westward from their homelands in the southeast and the so-called "Old Northwest" (the upper Great Lakes). One result of these uprootings was that during the decades before the Civil War, formerly separate Native societies now shared with one another a limited territory and a loss of sovereignty. Having created new lives for themselves in the southeast, they adapted once again to restricted quarters, as they struggled to preserve cultural identity In their new homes, they mingled traditions and integrated new trade materials into traditional arts. Migration brought displacement from ancestral grounds, and trade meant a shift from a self-sufficient subsistence economy to growing dependence on the market for hides and skins, furthered by reliance on guns and horses. To these challenges was added the growing volume of white settlement as the century wore on. Yet, as we have seen, Native artistic traditions throughout these decades paradoxically flourished , showing a technical and artistic inventiveness born of new threats to their cultural identity.

For many Easterners looking westward, coexistence with Indians was out of the question. Unable, or perhaps unwilling, to confront the historical dilemmas of westward expansion, many in the East, including artists and imagemakers, consigned Native cultures-very much alive though struggling- to the historical margins. Central to the ideology of white expansion into the West was the idea of wilderness: an image of the West as a space void of culture, empty and ready to receive civilization. The idea of wilderness was actively promoted by those who invested in the future of the West as a region that would replicate the institutions and middle-class domesticity of the East. Wilderness had no human past; it nullified the possibility of a middle ground, premised on an encounter between cultures. In the context of these deeply rooted cultural ideas, Native people of the West were confronted as obstacle, or as threatening other. Images of westward expansion as an inevitable tide of civilizing institutions in this sense went hand-in-hand with the political program of Indian removal, and a more general dehumanization of Native cultures.

The "Vanishing" American Indian

As the balance of power in the West shifted toward the claims of white settlers, Eastern Americans began to view Indian cultures as tragically doomed by history itself. Along with Catlin, many were able to imagine only one future for Native societies: to move progressively westward toward the setting sun, and inevitably toward extinction. These beliefs were shaped and encouraged by widely circulated images of Native people in postures of noble resignation and tragic defeat. Through constant repetition, the phrase "vanishing American Indian" acquired the aura of truth, in the face of the fierce persistence of real Indians.

THE "GOOD" INDIAN. Eastern audiences, themselves more than a century removed from conflict with Native cultures, dealt with their own moral misgivings about their government's destructive Indian policy by sentimentalizing the whole idea of the Indian. The "sentimental" version appearing in painting and sculpture, theater, poetry, and fiction-took its place beside the abused slave as an object of humane pity. Yet unlike the humane reaction to slavery, the figure of the idealized Indian did not produce any significant protest until nearly half a century later. According to the myth of the "vanishing''. American Indian, to protest his fate was to protest the course of nature itself, and equally pointless. The figure of the vanishing Indian also offered a measure of American progress; in a standard juxtaposition, the Indian gazes out from his wilderness prospect at factories, farms, and tilled fields-a vision of rising empire repeated everywhere from bank note engravings (fig. 7.11) to ambitious exhibition works such as Progress or The Advance of Civilization (fig. 7.12) by Asher B. Durand (1796-1886). In the most extreme expression of the theme, an Indian family stands on the western edge of the continent, contemplating the sun as it sinks below the horizon, the emblem of their defeat. There is nowhere else to go.

The "vanishing" American Indian in art reveals a nation torn between alternative identities: symbolically allied to nature and yet committed to its agrarian and industrial transformation. An emblem of America's difference from Europe, and its virtuous attachment to nature, the Indian in the arts also came to symbolize the nation's past-the subject of nostalgic regret for what had been lost in the rise to continental empire. The arts expressed a cultural ambivalence regarding change and the pace of progress, even as the national commitment to development drew generations of Americans toward an unstable future.

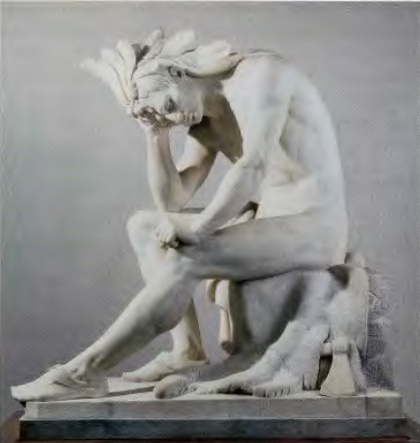

Thomas Crawford's (1813-57) The Indian: Dying Chief Contemplating the Progress of Civilization (fig. 7.13) embodied this ambivalence. The sculpture looks back to classical representations of the conquered barbarians of ancient Rome (such as the Dying Gaul), whose nobility is evident in the language of the idealized male nude.

A version of the Dying Chief was located within a series of emblematic figures on the east pediment of the U.S. Capitol (Senate) in Washington (fig. 7.14). A female allegory of the Republic anchors the sequence, which moves from soldier to merchant, schoolmaster, mechanic, and axe-wielding frontiersman, tracing a story of the nation's rise to power. The defeated Native cultures are wedged into the corners of the pediment, symbolically and literally pushed to the margins of history.

THE "BAD" INDIAN. The theme of the noble but doomed American Indian was, however, only one face of a dual image of Native cultures in the antebellum years. The heroic mission of establishing civilization required savage antagonists. From the Captiyity narratives of the early colonial period, in which white women were abducted and held captive by Indians, the 'bad" Indian was a fixture of American culture- a brutish enemy that furnished a convenient target for the regenerative violence of frontiersmen. Richard Slotkin has argued that violence against Indians was a ritualized act through which colonists gained control over their own most savage impulses. As white trappers and then settlers struggled to establish a foothold in the West of these years, what they feared in Indian cultures was often what they most feared in themselves-a descent into barbarism.

In Charles Deas's Death Struggle of c. 1845 (fig. 7.15) the intertwined bodies of Indian foe and bearded white trapper suggest a confusion of identities. The painting is a study in cliff-hanging sensationalism-the stuff of popular literature, tall tales, and Western almanacs. The outcome is in little doubt. Astride their steeds, Indian and trapper plummet headlong into a gulf whose obscurity intensifies the horror. The Indian clutches onto the trapper in one final effort to plunge his knife into his foe, even as the embrace suggests as well a desperate desire to save himself. Neither white nor Indian will come out alive.

Physically linking their fates is the small body of the beaver-the animal at the center of the international fur trade, whose economic value shaped the early phases of expansion into the West. Its paws still caught in the steel trap, it is the reason for the death struggle between white and Indian . Painted after the passing of the "trapper's frontier," Death Struggle imagines the West as a place of elemental violence and conflict between cultures over diminishing resources. Despite the symbolism of white and dark, with its moral imputation of good and bad, the helix-like formation of Indian, trapper, and beaver suggests that the identity of the white trapper on the frontier could never remain separate from those who shared the environment with him. Both Indian and white participated in the same system of international trade in animal pelts that was drawing the West into a market economy. Though exploiting the popular appeal of Western frontier violence, Deas's work looks beyond the frame to a wider world of violent economic and social competition.

The presence of the Indian in American arts and literature of the antebellum period invariably carried within it a narrative about the rise of the republic that framed both the "good" Indian-pure but doomed-and the 'bad" Indian-the embodiment of nature's darkest aspects, who needed to be mastered in order to establish a new culture in the West. This West of settlement was a place of moral absolutes, offering little in the way of a middle ground. Following the collapse of the trapper's frontier, which had seen the first artistic representations of Plains people, the next phase of expansion into the West would be driven by settler colonialism.

George Bingham and the Domestication of the West

In the decades following the passing of the explorer's and trapper's frontier, the literary and artistic figure of the pioneer emerged as one of the founding myths of the young nation-state in its transition to continental empire. Unlike the explorer's frontier, which looked to the West as a place of exotic difference and wondrous curiosities requiring documentation and preservation, the settler's frontier saw the West as an extension of the East. Here lay the nation's future, appointed by destiny to receive civilization through the heroic acts of its citizens.

DANIEL BOONE ESCORTING SETTLERS THROUGH THE CUMBERLAND GAP. George Caleb Bingham's painting of 1851-2 (fig. 7.16) distilled these beliefs for later generations. Beginning in the 1840s, nation-builders looked to Boone's pioneering qualities at a period in the nation's history when many felt the country was falling away from the revolutionary values of independence, stalwart individuality, and sacrificial courage. In the terms of the Boone myth which Bingham helped to shape, the settlement of the West was nothing less than a religious mission. But this was a vision that obscured the contentious politics of expansion: slave versus free; settler versus Indian; rancher versus farmer.

Dressed in buckskin, Boone strides toward the viewer, illuminated from above, the very type of the independent Westerner as the advance guard of civilization settling the wilderness. He is framed by a pyramid of settlers; at the apex is Rebecca Boone riding a white horse. According to popular accounts, Rebecca was the first white woman west of the Allegheny Mountains. Her appearance here is fittingly sanctified, the prototype of the "pioneer Madonna," whose pacifying and uplifting influence promised a new domestic stability to a region known for its rowdy men. Her thematic importance here is underscored by Bingham's dedication of the painting "To the Mothers and Daughters of the West." The deep space of the painting carries us through the stages of frontier settlement, from hunting, herding, and clearing the land to farming and domestication. The pioneer myth embedded in Bingham's work emphasized the sacrifices and difficulties of settling a wilderness-dramatized in the storm-riven and foreboding landscape. The biblical concept of wilderness served expansionists well, for it conveniently dispensed with all prior claims to the land.

BINGHAM'S AESTHETIC. Originally from Virginia, Bingham (1811- 79) passed his boyhood on the Missouri frontier, largely self-taught from prints until a trip to Europe in 1856. He was politically involved and committed to bringing Missouri out of its frontier isolation and into the broader life of the nation. But Bingham also understood the role played by art and aesthetics; the form, as well as the content, of his art carried a powerful message of integration and reassurance.

Bingham incorporated frontier into nation aesthetically by endowing regional or local figures like Boone with broad symbolic attributes, couching the pioneer pilgrimage of Boone's company in the biblical language of the Israelites passing through the wilderness on their journey to the promised land, with Boone cast in the role of the new Moses. Such allusions were familiar to a viewership steeped in the Bible. Bingham also framed his frontier themes, which lacked a history of representation, in the forms of past art. Anchored by the stable planar and pyramidal compositions of Renaissance painting, which he knew through print sources, he endowed riverboatmen, raftsmen (fig. 7.17) The Jolly Flatboatmen), frontiersmen, and low-life squatters with weight and dignity. Always with an eye to the market potential of images of the West, Bingham intended his boisterous western characters to take their place as national types alongside the Yankee figures who already occupied a secure place in national affections. His interest in creating national narratives and characters was shared by one of the leading art institutions of the mid-nineteenth century: the American Art-Union (see Institutional Contexts, page 228).

FUR TRADERS DESCENDING THE MISSOURI. Seeing a chance to shape the public's opinion of the West, Bingham sent works such as Fur Traders Descending the Missouri of 1845 (fig. 7.18) to the Art-Union to be engraved. Its patronage is evidence of the growing importance of the West in the public imagination.

Institutional Contexts: The American Art-Union

American Art-Union sought to foster the development of a national art and to democratize the practice of painting in America by extending the joys of art ownership to a middle-class audience. The Art-Union furnished a new source of patronage by providing young artists with national exposure and financial support through the purchase of original works of art. These were then engraved and entered into a national lottery., Subscribers to the Art-Union received one engraving a year, for the price of $5.00, while the lucky winners of the lottery received an original oil painting.

The Art-Union grew quickly into an immensely popular and influential institution. Paintings selected for engraving encouraged a sense of collective history and values based on historical figures and events, landscapes, and familiar character types. American frontier subjects seemed particularly suitable because they redirected attention away from the growing tension between North and South toward the region that represented the collective future of the nation, in theory at least. In 1853, the Supreme Court ruled the art lottery to be an illegal form of gambling, and the Art-Union soon came to an end. Its demise left artists once more dependent on individual patrons and the vagaries of the art market. However public-spirited, the Art-Union remained the work of private individuals; later efforts to foster national identity through the arts would be undertaken by the federal government in the 1930s.

The painting depicts a father and son gliding along a tranquil river in the wilderness. The trapper smokes a long-stemmed pipe that leaves a puff of smoke behind him, and he gazes off in the viewer's direction as he pulls his paddle. His raven-haired child, clad in a blue shirt and maroon trousers, leans over the covered cargo that they are taking downriver to a frontier settlement. The harmony between father and son mirrors their harmony with nature, embodied not only by the landscape but also by the leashed cub of undetermined species that occupies the bow as they ply the gentle river on this pristine morning.

Fur Traders invokes a series of primal encounters cast in a glowing light. The most immediately noticeable encounter is between men and wilderness. Another encounter is between child and adult; father and son. A third is racial: Bingham originally entitled the painting French Trapper and His Half-Breed Son, ensuring that the son would be understood as half-Indian. But since the reference to mixed parentage played on eastern fears about the mixing of races, he changed the title. A fourth encounter, more subtle, is between regions: the subjects of the painting are westerners, but the intended viewers were easterners (Bingham sent it to New York for exhibition), and the painting brings these disparate groups into implicit dialogue by having the figures in the boat make eye contact with the viewer.

This interaction served Bingham's intentions. Dedicated to improving the economy of his home state of Missouri, he wished to encourage investment and settlement from the East. Set a generation or so earlier than its execution, Fur Traders depicts a fundamental stage in the prospering of the West. It suggests that the region's present-day commercial activity originated in one of the most ancient and time-tested forms of Western enterprise, trapping and trading.

Unlike Bingham, the contemporary viewer is likely to think about the unacknowledged realities of race and gender that this painting glosses over. The nineteenth-century term "half-breed" disguised a complex reality: many French fur traders like the one in Bingham's painting took up with Native American women while on their long voyages. Some were true marriages, others relationships of convenience. Native women offered help with chores, and companionship, as well as crucial economic partnership: they were expert at processing the hides and pelts that were the source of the fur traders' income. As such, while invisible in this picture, women were an integral part of the success of the fur trade economy, whether their partners were Native or white.

The carefree life on the river that Bingham portrayed appealed to vast numbers of city-dwellers; low-cost prints of his paintings sold in the thousands. Bingham and his fellow artists provided viewers with images of a West of the imagination, a fantasy world of rugged and carefree individualism. Such images catered to the dream of a simpler life, flourishing on the frontier beyond the Mississippi: a life free of stress and class antagonism. While imagining the future nation as reaching from sea to sea, easterners struggled to assimilate the West-like an unsocialized child-into the family of the nation. Bingham minimized the unruliness of the West in favor of a reassuring image of a region tamed and civilized, its rough edges smoothed away, while preserving its appealing difference.

THE BAWDY WEST. Bingham's Jolly Flatboatmen treats a West of exuberant energies firmly locked into place by stable composition. His squatters, menacing Indians, and men without women take their place in an unfolding history of domesticating institutions that assured the region's eventual incorporation into the body of the nation. Popular media expressed a very different "West of the imagination." Western almanacs-cheaply printed pamphlets containing information on weather and farming conditions as well as tall tales-also published woodcuts of a bawdy West, where white men traded identities with Indians and grizzly bears, women straddled alligators, and nature was disturbingly alive and threatening. Spiced with allusions to masturbation and fornication, and accounts of eye-gouging and scalping, the almanacs presented a highly colored new frontier vernacular-both visual and verbal. A Tongariferous Fight with an Alligator, from an 1837 almanac (fig. 7.19), overturns gender hierarchies-in which women stayed home while men battled the wilderness-and disturbs the boundary between wild and civilized by showing woman and beast locked in mortal combat.

Charles Christian Nahl's (1818-78) Sunday Morning at the Mines (fig. 7.20)-a motley gathering of men in the California Gold Rush country-humorously exposes the worst fears of non-Westerners about the region. On the right, miners piously read the Bible, write letters home, and attend to domestic duties, while on the left, mayhem rules; other miners gallop horses through the gulch, and brawl in the background. One fellow, whose dark complexion and exotic looks suggest a racial mixture, is restrained by his companions as he drunkenly spills his precious gold dust from a scrotum-like bag. Here the wild freedom of the frontier appears as a place where libido is unrestrained by a disciplined work ethic. The productive economy of goldmining and other extractive industries is literally blown to the wind in the whirl of unbridled energies. The bodily excess and extreme behavior of this bawdy West was avidly consumed by young urban mechanics, laborers, and immigrants in the East, part of a popular culture that fed fantasies of frontier license and daydreams of escape from work, women, and family.