2.1: European Images of the New World- The First Century

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Since there are no surviving Native images from North America depicting their first encounter with Europeans, our selection is necessarily limited to images made by Europeans. (Significant exceptions to this come from Mexico and Peru, but these are outside our scope.) The sixteenth-century European images of the New World and its people reveal a range of attitudes, with roots deep in classical antiquity and Judea-Christian belief. During the first century of European exploration, conquest, and settlement, the wondrous news from the New World intermixed with the preconceptions of Old World myth and religion, producing a fanciful, at times distorted, image of its Native occupants, which has cast a long shadow across American culture and literature.

The Earliest Images

The earliest images of first encounter disclose more about European wishes and desires. than about ethnographic realities. Some time needed to elapse before those who voyaged to America were able to see its Native peoples- so radically different from themselves- with any degree of objectivity.

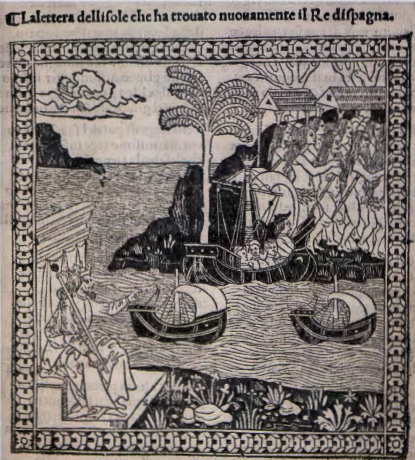

COLUMBUS LANDING IN THE INDIES. The first images of New World encounter were woodcuts produced in Italy to accompany Columbus's letter to his Spanish patrons (fig. 2.1). These images of Natives fleeing from the approaching Europeans are the only visual remnants of that first encounter. Broadly circulated, they represented the first "news" from the front, showing Europeans in terms of superior technology (ships), political power (in this print, a king, scepter in hand, establishes authority over the New World), and military might. But above all, it was the nakedness of the Natives depicted that lodged in European minds. Their Judea-Christian legacy associated nakedness with the innocence of Adam and Eve before their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Nakedness (as opposed to nudity) also conveyed vulnerability and the lack of defining traditions, rites, and religion- a cultural void upon which Europeans could project their desire for dominion.

PARADISE AND HELL. Europeans imagined the New World as both paradise and hell. The Old World's ambivalent image of the New is strikingly apparent in a woodcut published in 1505 in Augsburg, Germany (fig. 2.2) accompanied by lines from Amerigo Vespucci: "The people are ... naked, handsome, brown, well-formed in body [and] covered with feathers .... No one owns anything but all things are in common. The men have as wives those that please them, be they mothers, sisters or friends. . . . They also fight with each other. They also eat each other even those who are slain, and hang the flesh of them in smoke. They live one hundred and fifty years. And have no government." In the distant background are two Portuguese galleons, while the gruesome remains of two unfortunate sailors hang suspended from a tree. In the foreground cannibals gnaw upon severed body parts. Yet in the same print are blissful scenes of love beneath a wooden bower, nursing mothers and children, and stately men in feathered skirts and headdresses. The ideal of a paradise to the west, beyond the pillars of Hercules (Gibraltar), lived on from antiquity, shaping attitudes toward the New World. But coexisting with this was a fascination with what Europeans perceived as monstrous and savage behavior-nakedness, free love, cannibalism, and other practices threatening European notions of civilized life. This duality would persist through the next four centuries of European-Native encounters.

THE "NOBLE SAVAGE." The sixteenth-century encounter also inspired new ideas within European society. The exotic strangeness of the New World as a "bower'd" arcadia, where presumably no labor was required to pluck the fruits of the earth, and where "mine" and "yours" were unfamiliar concepts, delighted a Europe racked by prolonged wars and political and religious turmoil. Europeans marveled at a new people apparently without guile, selfishness, or inhumanity who appeared to be free of legal disputes, weights and measures, money, and books, as well as lying, deceit, joyless labor, greed, envy, jealousy, and dishonesty. Early descriptions associate the Indians of North America with a life of liberty and unfettered pleasure, living in a moral innocence unknown to jaded Europeans. Out of these first encounters was born the image of the "noble savage," the personification of ancient longings and new possibilities.

The Long History of the Feathered Headdress

THE EUROPEAN INVENTION of the Indian as a symbol of the New World began with the first sightings of the Tupinamba Indians of Brazil in the early sixteenth century; shortly thereafter, some actual Natives were exhibited to a European audience in Rouen, France. Very quickly, the most familiar attribute of New World people would become the feathered headdress and skirt, sometimes coupled in artistic imagery with severed body parts to indicate cannibalism. Feathered decoration made its appearance in countless allegorical representations of America-from English theatrical costumes to European tapestries, to wallpaper. Later, the feathered headdress became a symbol of the rebellious colonies. Such stereotypes of New World identity migrated freely between cultures for the next three centuries, serving many symbolic purposes. A range of indigenous cultures were collapsed into a single generic "new world" symbolized by the feathered headdress as an image of exotic difference. In the twentieth century, the eagle-feather headdress of Plains cultures would become an all-purpose sign of Indian identity, popularized by Hollywood and simultaneously adopted by Native Americans themselves to express pan-Indian identity.

A BECKONING PRINCESS. The nakedness of Native peoples fostered a quasi-sexual perception of them as vulnerable and receptive to European advances. Vespucci Discovering America (fig. 2.3) depicts a Renaissance explorer- an embodiment of masculine European knowledge and power- confronting a reclining nude Indian princess. Jan van der Straet (Stradanus), a Flemish artist working in Italy, furnished the 1589 drawing for a print honoring the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci. He holds an astrolabe-a measure of his navigational expertise and a banner bearing a cross, suggesting respectively the twin sources of his authority: science and religion. Beneath his scholar's cloak he wears armor and sword. Lying on a hammock, wearing only a feathered skirt and cap, the Indian maiden gestures toward Vespucci as if awakened by his presence. In the background, human limbs are roasting over a fire . Anteater, tapir, and sloth, as well as a pineapple, all make their appearance, meticulously labeled on the original drawing as new species. Exploiting a range of visual sources, Stradanus has amalgamated details from Brazilian, Caribbean, and Mexican cultures into a single image. Alongside a new empirical precision is the vision of an exotic and feminized new world receptive to colonization. This idea of a new world brought to life by its encounter with a superior European culture would persist in later allegories.

The Empirical Eye of Commerce

All sorts of misunderstandings attended the early encounters between Europeans and Natives. The newcomers misinterpreted indigenous people's relationships to the land, their gender relations, their artistic expressions, and their social organization. Some commentators marveled at what they saw; others disparaged it. The English settler and self-trained artist John White chronicled it carefully. His drawings depict an exotic land at the last moment before cultural encounter will change it forever. Subsequently, Theodor de Bry published editions of engravings based on the renderings of White and others, furnishing a visual chronicle of New World voyages.

JOHN WHITE. Beginning in the late 1500s, the English encountered the Algonkian peoples of Virginia and North Carolina-settled societies that subsisted by agriculture, hunting, and fishing. English would-be settlers-and the investors who financed their voyages-required practical information about the conditions awaiting them on the other side of the Atlantic. In 1585 John White accompanied the first English expedition to establish a colony on the eastern seaboard, on Roanoke Island, in present-day North Carolina. This venture, backed by Sir Walter Raleigh, was unsuccessful; but two years later, a second (also temporary) colony was founded there, and for this one White served briefly as governor. During the time of the first colony, he furnished his English sponsors with an extensive, detailed visual record of the land they claimed. In White's extraordinary watercolors, myth and preconception give way to studied observation.

White painted the Algonkian town of Secota, or Secotan (fig. 2.4), depicting it as an orderly place, with well laid-out fields of corn, tobacco, squash, and sunflowers. He indicated both a dancing ground (lower right) and a holy ground (lower left). Although White may have made the village look too neat and manicured, his outlines are probably essentially correct. Barrel-shaped dwellings were constructed of thin saplings bent over, lashed together, and covered with bark or reed mats. Often Algonkian women built such houses nestled under the protective shade of trees, as White depicts them.

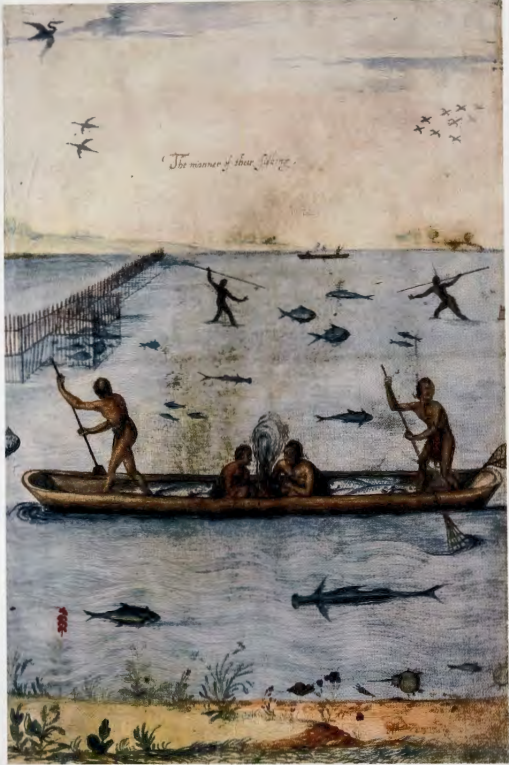

White's representations of Indian priests, conjurers, elders, women, and children provide details of the tattoos, dress, physiognomy, and customs of these Eastern Woodland societies-details highly useful to modern anthropologists and art historians. His figures turn in space and gesture as they spear fish in the shallow waters off the Carolina coast (fig. 2.5). Portraying the reed fences that the Algonkians used in trapping fish, he tilted the ground plane up, opening a space in which to include the varied marine life of the coastal waters. This rendering also employs a gridlike series of horizontals and verticals, which lock the variety of the natural world into order.

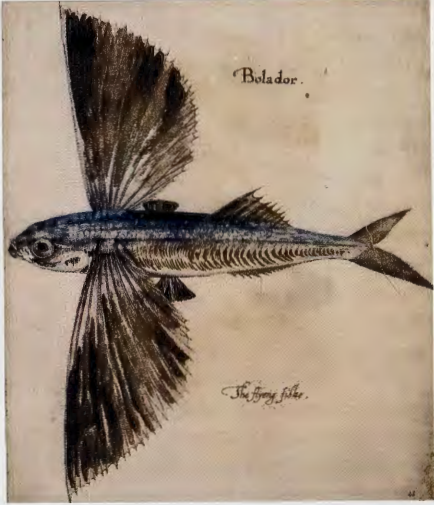

He painted a meticulously observed flying fish (fig. 2.6), which combines deft draftsmanship with information about coloration, gills and fins, and skin pattern. In like manner, he also drew land crab, scorpions, triggerfish, translucent Portuguese man-of-war fish, flamingoes, and reptiles: the most extensive body of natural history illustration yet inspired by the New World.

White's gridded vision of nature along the coast of the Carolinas, together with his precise rendering of native flora and fauna, reflect his European, post-Renaissance manner of organizing knowledge. Empiricism, with its focus on verisimilitude and inventory, served the emerging natural sciences and enabled Europeans to assert their dominance over indigenous cultures epistemologically that is, through their manner of knowing the world. Whatever may have motivated White to depict his new surroundings, his watercolors supplant an imaginary picture founded in myth and religion with an objective one based on observation and forethought, apprehending nature as an object of scrutiny, analysis, and economic exploitation.

Native depictions of animals also demonstrated keen observation. For example, the falcon pipe in the previous chapter (see fig. 1.8) combines accurate details of a falcon (feather shape, humped tongue, crooked beak) in an elegantly stylized abstraction, which allows the bird form to be wrapped and compressed around the bowl of a stone pipe. So although Native artists, too, observed nature closely, the result was stylized rather than strictly mimetic, in conformity with ritual and ceremonial norms.

DE BRY'S GREAT VOYAGES. The period between Columbus's arrival in 1492 and the English colonizing efforts of the later sixteenth century produced many written accounts of New World exploration, but few illustrations. However, in 1590 a family of engravers based in Germany undertook a major publishing venture that offered Europeans a richly imagined chronicle of New World conquests during the preceding century. The Great Voyages of the De Bry family was a compendium of fourteen volumes, written by various travelers, missionaries, colonizers, and adventurers, for which the De Bry family furnished the illustrations. The first book in the series was based on White's watercolors of the Virginia Algonkians, which Theodor De Bry had been quick to acquire. To his source materials, De Bry frequently added landscaped backgrounds, carefully observed anatomy, and perspective. Together, text and image gratified European curiosity, offering a reassuring picture of peaceful Indians in an exotic land of abundance. Later volumes in the series, however, featured horrific accounts of Spanish brutalities toward the Indians in Mexico, Peru, and Brazil. Such images played out Old World hostilities and rivalries; De Bry had himself suffered at the hands of Spanish oppressors in the late-sixteenth-century wars of religion between Protestant and Catholic. The composite picture the Great Voyages offered of the New World was complex and contradictory-both an Eden-like refuge from the worst excesses of European society and a land where European greed and plunder were acted out with ruthlessness and brutality.

New World Maps

Direct witness-such as that provided by White-played a major role in the British colonization of new lands. Hoping to encourage investment in Virginia (as the English then called all the lands they claimed on the eastern seaboard), early travelers emphasized marketable commodities, including fruits, fish, and building materials, as well as the supposedly receptive people. They also minimized the difficulties of planting a new colony. "The country about this place is so fruitful and good that England is not to be compared to it," observed Thomas Hariot in 1588 (A Briefe & True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia).

Knowledge was power, and maps offered another form of knowledge, which proved indispensable for the Spanish, Dutch, English, and French powers vying for control of the new continent. Maps were at times the object of espionage, as these rival powers attempted to monopolize geographical knowledge for private commercial interests. Although valued largely for their accuracy, maps also reveal their creator's motives, emphasizing some features while neglecting others, altering scale, and in some cases inventing geography.

Since the Middle Ages, a type of map known as a "portolan chart," used mainly by sailors, had emphasized coastlines, harbors, and points of entry into a continent over the interior features of new lands, thus promoting the expansion of international trade and overseas markets. By 1543, well after Magellan's circumnavigation of the globe (1519-22), the World Map of the Genoese cartographer Battista Agnese (fig. 2.7) traced the Spanish route across the Atlantic to the fabled gold riches of the New World in a manner that clarifies the imperial stakes that motivated exploration.

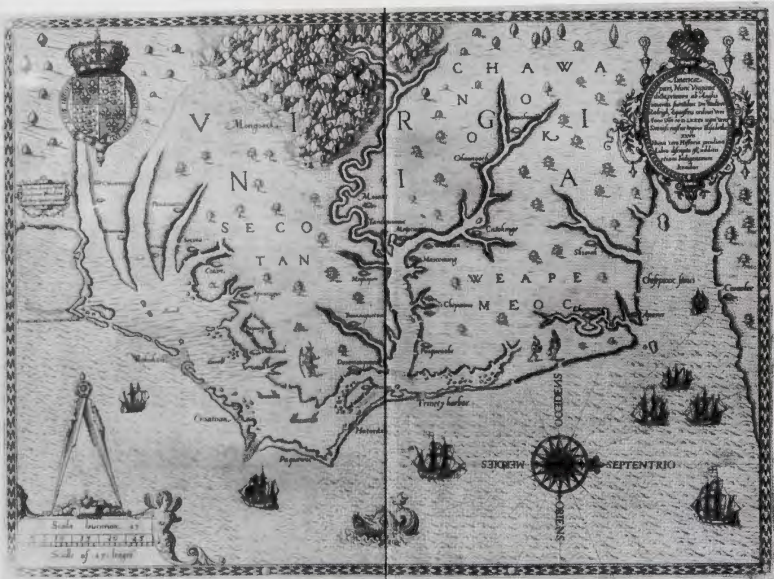

Emblazoned with the coats of arms of their imperial patrons, and devoid of references to the Native presence, maps also signaled possession of the new lands, in claim if not in deed. Over time, English and Spanish place names appeared in lieu of Indian names. In a map of Virginia based on one produced by John White and Thomas Harlot during the Raleigh expedition (fig. 2.8), Indian settlements are indicated by tiny circular stockades, and Indian names are retained. But larger block letters-"Virginia" - claim the new lands for the "Virgin Queen" Elizabeth; most of the map's information is contained between two stylized cartouches, further asserting the queen's proprietary stake in these lands. Overscaled galleons patrol the coastal seas, while tiny Indian figures appear stationed to greet the newcomers. Bisecting the land mass shown in the map is a wide coastal river that penetrates into the heart of the new land, leading directly to a mountain range shown at the top of the map. The scholar David Quinn has suggested that mountains not only served as geographical markers but also signified the possibility of gold in the interior. While providing useful geographical information about Native towns and passage into the continent, the sixteenth-century map of Virginia prepared adventurers and investors alike to see the region as a stage on which to enact dreams of wealth and possession.

Ceremonies of Possession

In the three centuries following 1492, rival European powers each established their own claims upon the land, wealth, and peoples of North America: England and France in Canada, France and Spain in Florida, England and Holland on the Atlantic seaboard in between, and-in the late eighteenth century-Russia in the Pacific Northwest. Although the dynasties and burgeoning commercial republics of Europe had different motives for colonizing, each sought to legitimize its presence in the New World, often by establishing alliances with Native societies. They did so by enacting what scholar Patricia Seed has called "ceremonies of possession," performed for the benefit of those already living on the land, as well as of those watching from Europe. 1 Declaring that the land was theirs, such ceremonies effaced all prior indigenous claims, at least in the minds of the colonizers. Ceremonies of possession varied from one colonizing nation to another, and each found expression in the visual arts. They tell us as much about the cultures of the colonizers as they do about the peculiar circumstances they faced in the New World. They also reveal a range of ways in which the first encounter was understood by Europeans, from the willed and arbitrary assertion of royal authority over conquered people to the middle ground in which European and Native maintained alliances on the basis of complementary needs and desires.

THE SPANISH REQUIRIMIENTO. Spanish ventures into the New World were accompanied by a ceremony known as the Requirimiento, or Requirement, by which the Spanish announced to uncomprehending Natives their intention of claiming the land for the Spanish Crown. With this proclamation went a demand that the Natives accept their new status as subjects of the Crown- the representative of the pope and his Christian empire. The Requirement did not demand instant conversion to Christianity, but merely consent to becoming peaceful subjects of the Spanish. This demand was followed by a threat to wage war upon any and all who refused these terms. "If you do not do it ... with the help of God, I will enter forcefully against you, and I will make war everywhere and however I can .. . and I will take your wives and children, and I will make them slaves .... " Instituted in 1512, the Requirimiento illustrates the autocratic character of the Spanish government, which during that time ruled by decree rather than by consent. The Requirimiento in turn reflected the experience of the Spanish themselves under Moorish occupation, when Muslim rulers exacted tribute from their Christian subjects. Now the Spanish turned the same methods on their New World subjects.

Rival colonizing powers were quick to seize on this feature of Spanish behavior in the New World, by circulating prints of Spanish brutalities toward the Natives. Over time, such events gave rise to the "legend of the Black Spanish," disseminated by critics within Spain, and then propagated by rival nations in their efforts to discredit Spanish claims in the New World. In such scenes as Theodor de Bry's The Landing on Espanola (fig. 2.9), the Spanish encounter with New World Indians is backed up by the threat of military force-halberds, swords, and cannons on nearby ships.

THE FRENCH AND THE TIMUCUA. Along with John White, the cartographer/ artist Jacques Le Moyne-a member of an early French Huguenot (Protestant) expedition to Florida in 1564-executed some of the earliest objective impressions of the New World. For example, Le Mayne's engraving of a palisaded village in Florida, showing several dozen low structures, some round and some rectangular, encircling a larger rectangular chief's house in a central plaza, suggests what Cahokia might have looked like some three hundred years earlier (fig. 2.10; see fig. 1.11).

In another, possibly more fanciful work, Le Moyne illustrates a ceremony that he witnessed (fig. 2.11 and p. 22)-placing a faceted obelisk, adorned with the fleursde-lys-the royal French coat of arms-at the center of his image. Its placement on the land marked French claims in Florida. On either side stand tattooed and elaborately coiffed Timucua Indians, who resemble performers in a French royal fete. The leader of the French expedition, Rene de Laudonnière, stands to the right, attended by helmeted guards. Such military protection appears unnecessary, however, as the central figure of Chief Athore gestures toward the obelisk and presses the shoulder of his European counterpart in a sign of acceptance. The local Indians have festooned the column with garlands of fruit and flowers, bringing gourds, squash, corn, bows and arrows, and other offerings in a show of respect to the French.

The Timucua probably interpreted this imperial marker as a sacred pole. Among many indigenous peoples, sacred poles were (and still are; see fig. 2.30) erected to signify a site where a ritual of cosmological significance takes place. In the Southeast, such poles were related to rituals of diplomacy. In the seventeenth century, the French explorer La Salle and his expedition took part in such rituals with Quapaw and Caddo Indians, in what is now Arkansas. Wooden poles were erected and festooned with gifts for the foreign visitors. Brave men, French and Native alike, were expected to strike the pole with tomahawks and recount their deeds of valor. Such ceremonies were meant to cement diplomatic ties, transforming strangers into trading partners and allies.

In his history of his own expedition, Laudonnière relates how the friendly Indians of Florida compelled him to share their idolatrous worship of an object actually intended to establish French sovereignty over their lands. Laudonnière and his men apparently mistook a ceremony of high diplomacy for one of "idolatry"-the only category the French had for interpreting such actions. The French believed that the obelisk established their claim on the land; the Timucua took it to be a symbol of diplomatic exchange, assimilating foreign visitors into their own system of ritual. The scene is an example of what historian Richard White calls "expedient misunderstanding" between cultures, in which each side interprets symbolic events in a manner that reinforces its own belief systems while contributing to cultural alliances.

THE ENGLISH: TAKING POSSESSION OF THE LAND. Right of ownership, according to English law and history, went to those who not only inherited land but who invested labor and time in it. As concepts of private property matured, the delineation of ownership through fencing, agricultural fields, houses, and other markings connoted the establishment of a civilized order. From the first permanent English settlements in North America-in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 and in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620-through the centuries of westward expansion, Anglo-Americans took possession of the land through acts of surveying, laying out grids, and drawing boundaries. In the process they created, in the words of environmental historian William Cronon, "a world of fields and fences."

The image of the new land as a garden, marrying natural abundance to the improving hand of the gardener, was deeply rooted. It also resonated with the biblical call to God's "chosen," the Jews, to go forth into the wilderness and in the words of the Book of Isaiah, make the desert ' "rejoice and blossom like the rose. " This faith took many forms over the next three centuries, and found its grandest expression in the late nineteenth century, when the American West became the focus of scientific investigation, resource extraction, and settlement.