2.3: Northern New Spain- Crossroads of Cultures

- Page ID

- 231687

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)From Columbus's first landfall up to 1700, Spain was the foremost colonial power in Europe. At its fullest extent, the Spanish empire in the New World spread from the tip of South America to its farthest point north in what is now St. Louis (fig. 2.24). Spain's North American empire, stretching from California to Florida and the Caribbean, was administered from Mexico City, which in turn reported to Seville, ·the imperial center across the Atlantic.

During the years when it established its New World empire, Spain was a cosmopolitan society combining classical, Islamic, and Christian influences. These influences are apparent in the architecture and arts of its New World colonies. Ancient Roman domination of the Spanish peninsula had left a substratum of classical influences on language, politics, urbanization, and architecture, including the arch and its related form the barrel vault. In the centuries following the collapse of the Roman Empire, the Visigoths invaded from northern Europe, followed in the eighth century by the Moors from North Africa. In 1492 the Spanish Crown embarked on a phase of aggressive Christian proselytizing. This precontact history would shape the attitudes of Spanish colonizers toward the Indian cultures they encountered in the Americas.

Brutally "pacified" in 1598 by Juan de Oñate, New Mexico was a colony of a colony (Mexico City), twice removed from the imperial center in Spain. This remoteness meant that colonists developed local building traditions, invented new solutions to old problems, and created forms of religious devotionalism unique to New Mexico. As in other isolated places, expressive forms-whether in architecture, language, or music- have persisted, with great vibrancy, into the present.

When the Spaniard Francisco Vásquez de Coronado and his men set forth from Mexico in 1540 in search of the rumored golden cities of the north, they encountered a vast Pueblo world of some one hundred fifty flourishing towns, inhabited by the descendants of the Ancestral Pueblo peoples who had lived there since the late thirteenth century (see Chapter 1). The explorers, impressed by the apartmentlike compounds of these diverse villages, gave their inhabitants the collective name Pueblo Indians, from the Spanish word for "town" or "people." Over the next centuries, some aspects of Pueblo art and culture were retained, while others fused with the traditions of their Spanish conquerors.

What produced this fusion of cultures, despite a resistant and periodically militant population of Indians that far outnumbered the newcomers? How did the Native inhabitants assimilate, subvert, or adapt the new artistic and architectural forms of the Spanish? And how was the Spanish inheritance transformed in turn? Today, a handful of small villages along the Rio Grande, the western New Mexican villages of Zuni and Acoma, and the Hopi villages in northern Arizona, are all that remains of the dozens of towns that the Spanish reported finding. How is it that, despite Spanish efforts to subdue and convert the Natives, Pueblo and Hispanic cultures melded so successfully? How is it that the descendants of the inhabitants of Pecos Pueblo still prize the ceremonial cane of authority bestowed upon their ancestors by the king of Spain in 1620? All of these questions form the subject of this section.

A "Bi-Ethnic" Society

Long before European contact, the Pueblo Indians had traded with distant peoples. Pecos, for example (see fig. 2.36), was already a trading town when the Spanish arrived in the sixteenth century, so the newcomers merely expanded the networks already in place. Following colonization, New Mexico, despite its isolation, was part of a global exchange in raw and finished goods- the farthest frontier of a trade empire centered in Spain but extending to the Far East, as well as to Peru to Argentina. The Camino Real (Royal Highway-though in reality it was a dirt road), beginning at Taos and ending at Mexico City, linked New Mexico to its colonial center in a trip that took from five to six months. This lifeline of empire supported a vital traffic of raw materials, finished goods, skilled labor, and institutions on which frontier settlers vitally depended.

The arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century-and the renaming of this region as "Northern New Spain"-began a four-centuries-long process of intercultural influence. While striving to suppress indigenous traditions, often through violent means, the Spanish presence in fact dramatically expanded the creative and material resources of Pueblo societies, introducing new materials, design traditions, and building forms. And it did the same for Spanish forms brought from the Old World. The blending of Hispanic and Indian cultures in the Southwest changed the texture of each in profound ways, resulting in a bi-ethnic "Indo-Hispanic" society. Intermarriage, cultural exchange and adaptation, and a shared physical environment promoted productive coexistence. Images of the Christian saints found places of honor in the pueblos of the Rio Grande Valley, alongside Native practices. Native and Christian ceremonial days came to overlap in the yearly round of ritual and celebration.

Compared to the middle ground of the eastern colonies, Indo-Hispanic culture was marked by a much stronger convergence of traditions and materials. Both the Pueblos and the colonists had traditions of adobe or baked mud construction; both drew upon religious forms that favored ritualized expression, public festival, and communal worship. New Mexico differed from the middle ground of the Northeast in another respect: the Spanish-unlike the French, who were interested primarily in trade- had come intent on establishing their religious and physical presence over Native cultures. Though skewed by the imbalance of power, a melding of Spanish and Indian cultures was achieved, producing the distinctive regional identity of the Southwest today.

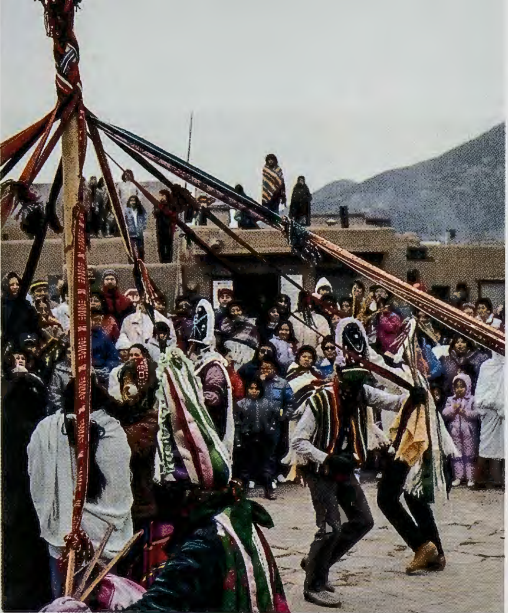

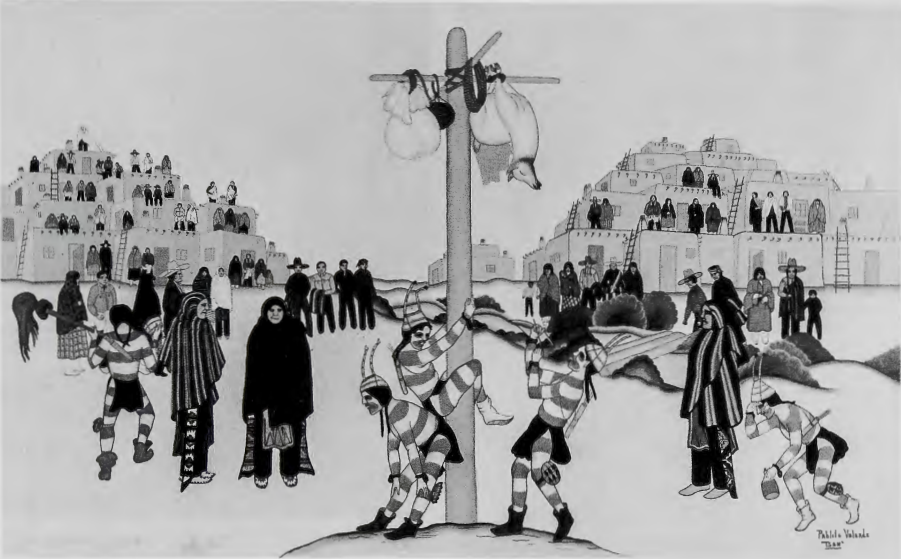

THE MATACHINES DANCE. A ritual performance that takes place in both Pueblo and Hispanic communities in New Mexico is the Matachines dance (fig. 2.25). Anthropologist Sylvia Rodriguez has written that "the Matachines dance symbolically telescopes centuries of Iberian-American ethnic relations and provides a shared framework upon which individual Indian and Hispanic communities have embroidered their own particular thematic variations." We include it here as a window onto the possible nature of intercultural encounter more than three hundred years ago and as an illustration of the longevity of these traditions.

In indigenous villages such as Taos, San Ildefonso, and San Juan, as well as in the neighboring Hispanic communities of Bernalillo and Alcalde, the Matachines performance takes place at Christmastime or on the festival of the community's patron saint. A dozen dancers wear headgear that looks like a bishop's miter, decorated with streamers, scarves, fringe, and silk cloths that sometimes mask their faces. A king, a bull, a little girl, and some ritual clowns known as abuelos (grandparents) complete the troupe.

The name of the dance comes from Renaissance Europe, where a "matachin" was a costumed sword dancer or a harlequin. In Conquest dances throughout Latin America and the American Southwest, Native and Hispanic performers reenact the conquest of the Moors (North Africans) by the Spanish Catholics in the fifteenth century, an event that prefigured the later conquest of New World peoples. Centuries ago, this ritual drama-first performed by the Spanish to celebrate the Conquest-may have been imposed on indigenous performers, but today it has been incorporated into Pueblo culture and modified to tell their own version of events. Native and Hispanic communities attribute different histories to the dance. Pueblo traditions relate that the sixteenth-century Aztec ruler Montezuma himself brought the dance from Mexico (though, in fact, there is no evidence that any Aztec king ever traveled that far north). In their dance, the figure named El Monarca (the king) stands for Montezuma. In Hispanic communities, the standard interpretation is that the Matachines dance was first performed by the Spanish, who reenacted the Christian conquest of the Moors when they conquered New Mexico in the late sixteenth century.

Although not a feature of all Matachines dances, a maypole is commonly seen at Taos, where the dance is performed repeatedly on December 24, 25, and 26. The dancers, holding streamers made of long wool belts attached to the top of the pole, wind around it in time to the music, some moving clockwise, others counterclockwise. Although the maypole is European in origin, it may have had particular resonance at Taos, where an indigenous festival involves the use of a pole climbed by clowns (see fig. 2.30). The linkage of poles and clowns is yet another example of the convergence of cultures that takes place in a situation of colonial encounter, allowing new traditions to be formed.

The abuelos, a combination of buffoons and stage managers, police the event and provide acerbic commentary on gender or ethnic relations, or on simple human foibles with which all viewers can identify. Today, they wear ski masks, chimpanzee masks, and even masks depicting the American president. Though the maskers are male, one may take the role of grandmother, so cross-dressing and the burlesque of female behavior by male players is part of the entertainment as well.

The abuelos seem also to be a latter-day variant of the ancient ritual clowns of the Southwest, whose important role is to guide the ceremony and provide irreverent commentary, humor, and ridicule. In the Hispanic communities, the Matachines dance not only commemorates the coming of their ancestors from the Iberian Peninsula to northern New Spain but also expresses a twenty-first-century Hispanic determination to persist in the face of the dominant English speaking culture of the United States. As Sylvia Rodriguez comments, like the maypole itself, around which the Matachines weave, "the dance is a living composite of diverse received and improvised multi-colored elements, braided together through the collective act of performance."

In centuries past, the Matachines dance acted out the contest of cultures on the frontier of colonization, while fusing elements of Spanish and Indian ritual life. Embodying both encounter and resistance, the Matachines is a vivid example of the inventive new forms that evolve at the meeting of divergent cultures.

Pueblo and Mission in New Mexico

Of the southwestern states that trace their beginnings to Spanish colonization, New Mexico was converted first and most successfully. Within twenty-five years of the conquest in 1598, there were ninety Christianized pueblos, twenty-five mission churches, and numerous smaller churches. From 1581 to 1680, Spanish officials and Franciscan friars organized the conquest of what came to be called "The Kingdom of New Mexico." Pueblo people were forced to repudiate their traditional religion. Ceremonial masks and other regalia were seized and burned. Crosses and churches were erected, kivas destroyed. Catholic priests tried to stamp out indigenous ritual dramas, substituting theatrical liturgies concerning Jesus, Mary, and the saints, as well as public performances commemorating the battles of the Moors and the Christians. Due to warfare and smallpox epidemics (as well as periodic droughts), the Pueblo population was reduced from approximately sixty thousand at the beginning of the seventeenth century to fewer than ten thousand at the beginning of the nineteenth. In addition, Spanish colonists exacted tribute and forced labor from the mission Indians ' despite Franciscan efforts to protect them from exploitation.

Pueblo society freed itself from this stranglehold for a few years when, in 1680, many villages banded together to overthrow the Spanish, successfully driving them out of New Mexico for twelve years. In this short period after the Pueblo Revolt, as it is called, Native people turned the tables on their conquerors, burning churches and crosses, and reconsecrating their kivas. Because of this destruction, very little of the Spanish missions of the seventeenth century remains intact. Following the reestablishment of Spanish rule in 1692, aspects of traditional Pueblo religion were once again driven underground-the only way they managed to survive. Yet the conquerors succeeded only in creating a multilayered religious, artistic, and performance tradition, one encompassing both Christianity and ancient Native worldviews.

Only after the Spanish reformed the oppressive colonial system that had sparked the rebellion were they able to resume their conversion of the Pueblos. Many more mission churches were built, some of which are still in use in Pueblo villages today. Alongside the indigenous kivas and dance plazas, these churches are at the heart of community life. Even today, European-derived dances may be performed in front of a church one day, and an indigenous animal masquerade performed the next.

Santa Fe Fiesta-Reenacting the Conquest

ANOTHER FESTIVAL PERFORMED YEARLY in New Mexico marks the imposition of a European colonial order onto the new land. Around Labor Day, the city of Santa Fe stages an elaborate fiesta, which lasts several days and includes mass spectacle, dramatic reenactments of history, pageants, costume parades, a candlelight mass, an Indian market, and staged plays, along with those three essential elements of a festival-music, dancing, and feasting. Unlike the Matachines dances, which also mark the arrival of the Spanish, Santa Fe Fiesta from its beginnings has given pride of place to the Hispanic history of conquest and settlement. In recent years, however, historical tensions have surfaced around Fiesta in a revealing manner.

The Santa Fe Fiesta traces its history to 1712 and lays claim to being the oldest communal festival in North America (a claim that overlooks the far more ancient indigenous festivals). Its modern form , however, dates to 1919. At the core of Fiesta is the commemoration of the 1692-93 reconquest of New Mexico after a revolt in 1680 by Pueblo people. During the central pageant, costumed players reenact the planting of the Cross by Diego de Vargas and his Spanish soldiers in front of the Palace of the Governors in 1692 (fig. 2.26), commemorating the peaceful return of the Spanish to New Mexico. De Vargas then reads a proclamation to the assembled Indians, similar to the Requirimiento. The procession of an effigy of New Mexico's patron saint, Nuestra Senora de la Conquista, or "La Conquistadora," through Santa Fe occupies a place of symbolic importance in Fiesta , which also commemorates the restoration of Catholicism after the revolt. The pageant, however, neatly sidesteps the bloody siege of Santa Fe in 1693 which followed the initial reentry of the Spanish. Instead, Fiesta reenacts the colonial history of New Mexico as a process of peaceful coexistence, a "commemoration of the reunion of two peoples," as a 1933 description carefully emphasized. Santa Fe Fiesta directed at ethnic reconciliation-depends on the willing participation of all groups, including those very Pueblo Indians who, for historical reasons, may feel they have little to celebrate. Although they have in fact been central players in the cultural history of New Mexico, Pueblo participants in Fiesta have felt marginalized, as they are made to play the role of secondary actors in the larger story of Spanish dominance. In 1977 the All Indian Pueblo Council staged a boycott of Fiesta, and the event has continued to trouble ethnic sensitivities lying just below the surface. At their best, festivals offer opportunities to experiment with new forms of social, gender, and ethnic relations. However, as the organizers of Fiesta have come to understand in recent years, it also opens up old wounds.

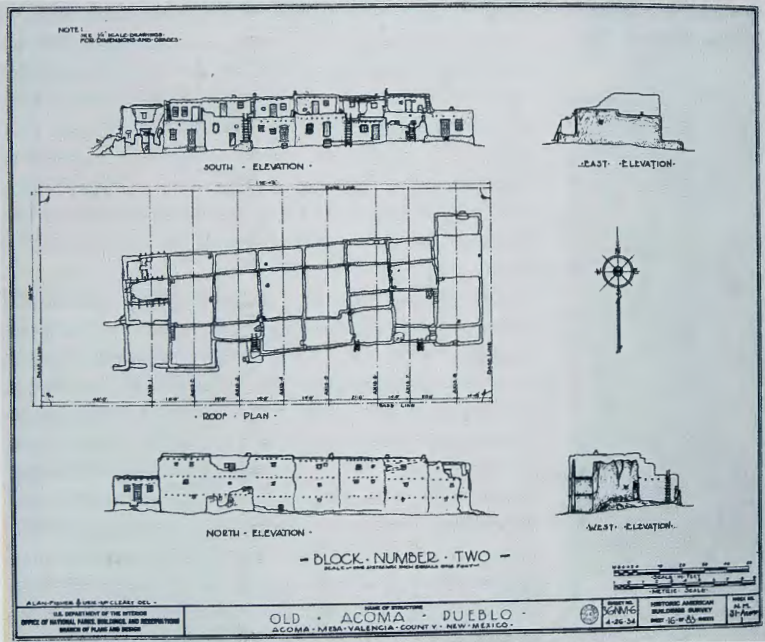

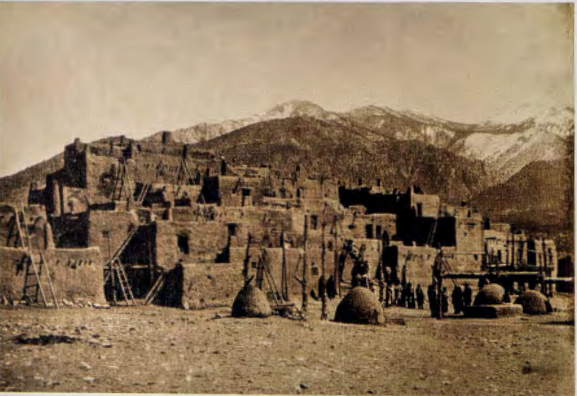

ACOMA. Long continuities of Pueblo architectural tradition coexist with changes brought by the Spanish. The multistory apartment compounds of Acoma Pueblo (fig. 2.27) have been rebuilt and altered over many centuries. Built atop an easily defensible mesa and known as the "Sky City," Acoma, some 60 miles west of Albuquerque, dates back at least to the thirteenth century. On the south side of these compounds, each succeeding story is set back from the one beneath it, creating rooftop outdoor working space. Similar stepped terraces were found in Ancestral Puebloan architecture (see fig. 1.17), at Pecos in the protohistoric era (see fig. 2.36), and are still in use at Taos, where they serve as viewing stands for ceremonies in the plaza below (see figs. 2.25, 2.29, 2.30). These south-facing setbacks maximize exposure to the sun, to aid in drying fruit or corn for winter, or drying laundry. They also serve as a passive solar heating system, keeping the interiors warm in the winter. The north face of the apartment compound, in contrast, is a three-story adobe wall, punctuated only by small windows, with no entrance (fig. 2.28).

The elevation drawing shown here comes from a rich record of photos and architectural drawings of Acoma Pueblo that was made in 1934 by the Historic American Buildings Survey, one of the New Deal projects organized during the Great Depression. In 1960, Acoma was designated a National Historic Landm ark, in recognition of its status as the oldest continuously occupied town in North America, its roots stretching back nearly a millennium. While such antiquity may be commonplace in European and Asian cities, this is an impressive duration of time in a nation whose historical founding dates only to 1776.

ADOBE: CONVERGING TRADITIONS. While ancient construction techniques favored the use of locally quarried stone, most historic Pueblo architecture uses adobe bricks. Handmade in wooden molds by members of the community, adobe blocks were an innovation introduced by the Spanish. The Pueblo themselves organized the work along traditional gender lines- the men doing the construction and the women plastering the walls with wet mud to provide a durable coat over the mud bricks.

The Spanish had adapted adobe construction from the Arab cultures of North Africa and the Near East ("adobe" descends from the Arab word atob, or 'brick"). It had been introduced into Spain with the Moorish invasion from North Africa in the eighth century. In those places, as in the American Southwest, it was well suited to the dry climate. The Native tradition of puddling predated the Spanish conquest and continued to be used at Taos Pueblo. This involves hand-packing mud into walls, sometimes over stones, or an armature of thatch and wood. This puddling and hand-plastering influenced the sculptural quality of Hispanic adobe buildings such as the apse of the church of Saint Francis of Assisi, in Ranchos de Taos, painted and photographed numerous times over the past century. Another example of cultural migration and adaptation is the homo, a beehive-shaped outdoor oven (fig. 2.29, foreground). The form- like adobe itself- originated in the Near East, coming to Spain in the eighth century, then migrating to New Spain and spreading up to New Mexico with the first frontier settlements. The Pueblo Indians then adopted the homo , and today it can be seen throughout the Pueblo villages of northern New Mexico, where visitors often assume it is an indigenous form.

Most of the Rio Grande pueblos, including Taos and Pecos (see fig. 2.36), were built on the valley floor, rather than rising up out of a rock outcropping. At Taos, two apartment complexes, a north and a south house block, rise on either side of the vast dance plaza, which is bisected by a stream. Behind them rises Taos Mountain, the pyramidal shapes of the apartment complexes echoing its shape. Taos's north house block rises to five stories in some places. This basic architectural form has persisted for more than a millennium. The dance plaza is the focus of the architectural and ritual environment, for it is in ceremonies held there that people demonstrate the reciprocity between their world and the spirit world. Some-like the Matachines dances- are mixtures of Native and Christian belief and iconography. Others are ancient in format and substance- like the koshares (clowns) of Taos Pueblo, with their characteristic gray-and-white striped bodies (fig. 2.30 ). Dating back many centuries, the koshares were first depicted on pottery painted around 1100 C.E. (see fig. 1.20). The Pueblo clown instructs by acting out the antithesis of proper behavior in a manner that symbolically inverts the established order.

Architecture in the Southwest- like ceremonial forms- is a mixture, arising from the political and religious agendas of the conquerors and the preexisting traditions of the indigenous people. Spanish colonization in New Mexico proceeded along the networks of established settlement, building missions within existing Pueblo villages. New Mexico's missions were typically run by the Franciscans, and consisted of a church with an adjacent "convent," which housed one or more brothers- thus being a small scale, frontier version of a European monastery. Conceived by the Spanish clergy as a step on the path to civil or secular parishes, these missions were a critical element in the colonization of the frontier of New Spain.

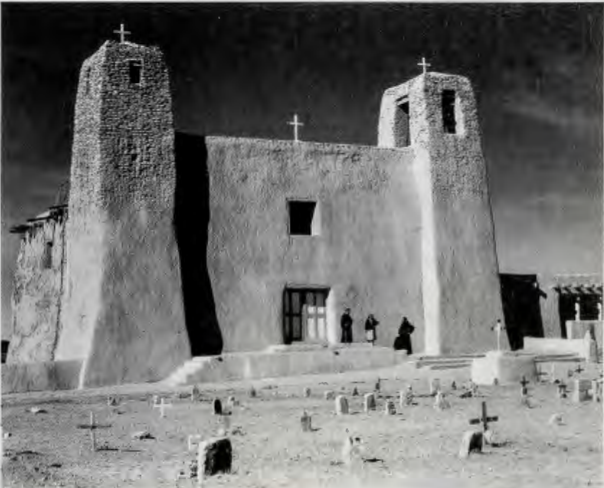

THE MISSION AND CONVENT OF SAN ESTEBAN AT ACOMA PUEBLO. The oldest example of New Mexico's missions is San Esteban, at Acoma Pueblo. Named after Saint Stephen, the Church of San Esteban (fig. 2.31) is located on a slight rise, apart from the Native dwellings that extend across the mesa.

To the right of the church is the convent's cloister ( a courtyard with a surrounding covered walkway), the private quarters of the friars, and other monastic buildings. Franciscan missionary efforts at Acoma had begun in 1623, and an ambitious building program soon followed. Although its original fabric dates from sometime between 1629 and 1664, the complex was restored and rebuilt many times; a series of twentieth century restorations has further modified the original structure. Larger than later mission churches (the nave height soars to 50 feet), San Esteban recalls the fortress mosques of the Arab world, which left their imprint on Spain. Its size and mass- as well as its location, atop an inaccessible mesa-made it virtually invulnerable to attack and announced to the surrounding Indian pueblos that New Spain had successfully subdued the Acoma Indians, who had most fiercely resisted colonization. Aspiring to the proportions of the great sixteenth-century cathedrals of Mexico, San Esteban asserted the power of the church over newly Christianized Natives-in part by being constructed right in the heart of the village.

San Esteban was built by Pueblo laborers supervised by a Franciscan from Mexico named Juan Ramirez. The Indians of Acoma worked with Ramirez to realize an extraordinary building campaign, manually dragging huge timbers for the roof, harvested 40 miles away, and field stone (used in tandem with adobe), up the 400-foot cliff from the plains below. Like most colonial religious structures in New Mexico, San Esteban consists of a single nave without transepts (fig. 2.32). The width of the nave (33 feet) is established by the length of the spanning timbers (or vigas). Their hewn ends project from where the roof and sides meet. The use of vigas to span roofs was a feature of Pueblo architecture easily adapted to Spanish mission buildings. Using Native mud-and-rubble construction methods, the Acoma builders widened the base of the walls to support their weight, and built massive buttresses at the nave ends. These structural modifications produced the battered profile characteristic of New Mexico churches. The flat plane of the facade is broken only by two massive towers. In front is the burial ground, also used for outdoor preaching. This atrium-like space, surrounded by a retaining wall 45 feet high in places, was a feature of many mission churches throughout New Spain. Such outdoor spaces, animated by ritual and performance, were already familiar to the Pueblos, with their traditions of communal ceremony.

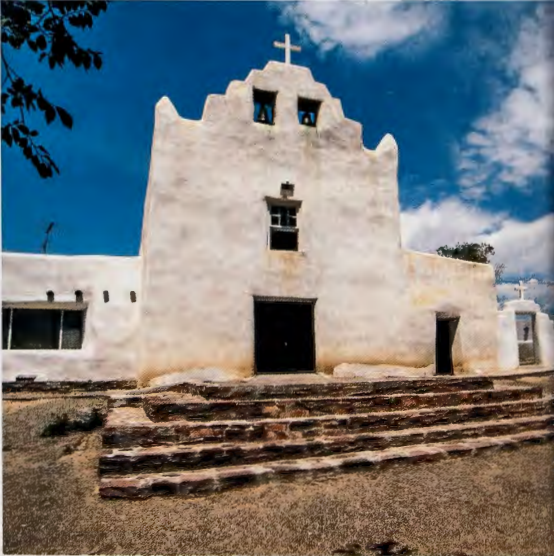

THE CHURCH OF SAN AGUSTiN AT ISLETA PUEBLO. In a related example, there is evidence that the Spanish Franciscans of New Mexico oriented their churches so that the light of the winter solstice on December 22-a day of key importance in the ritual life of the Pueblos-would illuminate the sanctuary, holding the image of Christ, at the end of the nave. The invention of the transverse clerestory window, seen at the Church of San Agustin, at Isleta Pueblo, near Albuquerque (fig. 2.33), brought lighting into the altar and choir area through a window running across the nave at the point where the higher roof meets the lower sanctuary. By illuminating the sanctuary on the winter solstice with effects resembling Baroque lighting, the transverse clerestory window effectively translated Native practice into Christian form, creating architecture and symbolism that resonated with Pueblo and Hispanic Catholics alike.

THE MISSION CHURCH AND CONVENT OF SAN JOSE AT LAGUNA PUEBLO. The mission of San Jose at Laguna Pueblo (north of Acoma) also fuses Pueblo and Hispanic Catholic cultures. The stepped outline of the adobe exterior, painted white (fig. 2.34), frames two bells, which regulated the lives of the Pueblo converts. The step motif asserts Pueblo symbolism in the very midst of Catholic authority (see fig. 9.28). The interior contains another example of mixed traditions.

On the ceiling above the altar is a buffalo-skin canopy (fig. 2.35) painted by Indian artists and depicting a sun embellished with stepped cloud motifs and zigzagging arrows, moon, rainbow, and stars, all elements deriving from Pueblo culture. Such symbols can also be found in Christian iconography as attributes of the Virgin and other religious figures. Did the Franciscans of New Mexico simply tolerate the intrusion of Native belief systems into their church? Or did they, like the friars proselytizing among the Aztecs and other indigenous peoples in Latin America, make deliberate use of parallels between Native and Christian practices in an effort to encourage the Indians' conversion to their own faith? The point remains debated, yet the wisdom of such a strategy-adapting to local conditions-became more evident after 1692: the mission at Laguna was founded soon after the Pueblo Revolt.

Today, Pueblo Indians who practice Catholicism continue to use and maintain the mission churches of the Rio Grande Valley. Yet despite missionary efforts to replace the ancient Pueblo spirit helpers with the Christian Savior, powerful ties to ancient history have helped preserve Pueblo identity over more than four centuries.

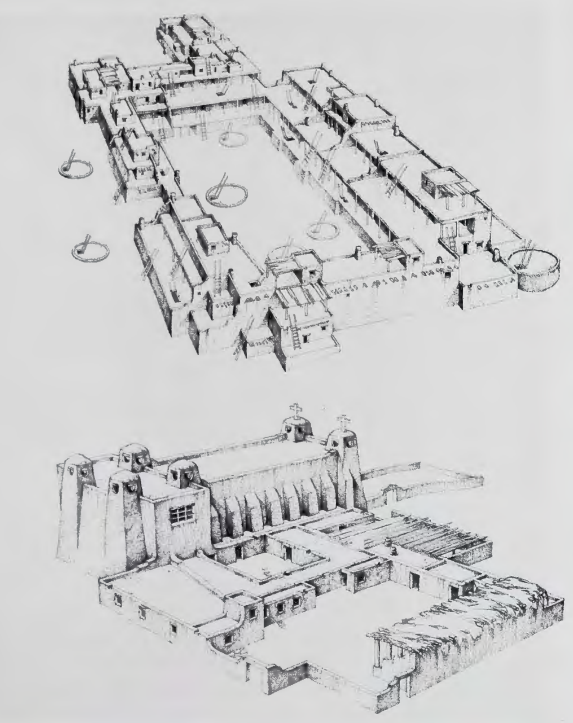

PECOS PUEBLO AND MISSION: AN INTERCULTURAL ZONE. Mostly abandoned by the early nineteenth century, Pecos Pueblo and Mission is among the most thoroughly documented archaeological sites in the Southwest (fig. 2.36). For over a millennium, it has been at the center of the historic changes that have made New Mexico a region of cultural encounter, playing a key role in trade, and serving as a gateway to the Great Plains to the north and east. Architecture and material remains, along with historic documents, shed light on the dramatic events centered in Pecos: trade, warfare, domination, rebellion, reconquest, and the eventual abandonment of the town.

Pecos was founded around 800 C.E. at a site in north central New Mexico that was advantageous for trade. It had access eastward to the river systems that extended into the southern Plains, as well as south along the Pecos River and west to the pueblos along the Rio Grande. Ancient trade goods found at Pecos included shells from the Pacific and the Gulf of Mexico, flint artifacts, pottery, and shell beads. By 1400 C.E. , multiple-room and multistory apartment complexes-like those at Acoma and Taos, but made principally of cut stone-were well established. From Coronado's first exploratory foray into New Mexico in the 1540s, the Spanish colonizers found a prosperous community- more than two thousand people living in four-story apartment complexes, which had more than a thousand rooms and twenty-six kivas. They were impressed, remarking that its buildings were "the greatest and best of these provinces." Pecos was a vibrant trade center: substantial amounts of corn, chili peppers, and beans were stored there, and buffalo hides from the southern Plains were traded for cotton textiles, pottery, and turquoise from the Pueblos.

At Pecos today, one can see the "footprint" of the ancient multistory pueblo, and the thick walls of the early eighteenth-century mission church. The reconstruction drawing (see fig. 2.36, upper drawing) demonstrates what a substantial building the north pueblo was. The ground floor of the sixteenth-century pueblo consisted mainly of storage rooms, while the second, third, and fourth floors contained apartments. The need for protection against enemies and the conservation of heat is evident in the small number of windows and external doors. In times of defense against marauding Apaches and Comanches ( or later, Spaniards), the ladders-here as at other Pueblo communities-could be pulled up.

The conquest of New Mexico proceeded in fits and starts, and from the beginning, Pecos was at the forefront of these efforts. Following their initial resistance to the first armed entry of Spanish soldiers in 1591, the Pecos Indians allowed Franciscans to dedicate a small mission there in 1617 / 18. This was followed shortly by the construction of the largest church in all of Northern New Spain to accommodate the large population of Indians, under the direction of Father Juarez, a Franciscan (see fig. 2.36). Its massive appearance-with walls up to rn feet thick at the sides, six towers, and a series of buttresses along the nave-recalled the Muslim fortress, later reclaimed by Christians, in Father Juarez's hometown near Cordoba, in Spain. An adjacent one-story building contained the priests' quarters, stables, and workshops. All of this was built by Pueblo workmen under the direction of Juarez. This impressive frontier building was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, but replaced in 1717 with another, smaller structure. Following the revolt, the Pueblo people built subterranean kivas in the quarters of the Catholic priests to reassert their own religious and architectural traditions, using adobe bricks salvaged from the burned church.

Following colonization, Pecos retained its importance as a trading center. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the town was the site of vast trade fairs, which drew Indians from all over the Southwest and the southern Plains- traders from Mexico and all the way from St. Louis. Pecos pottery has been found as far away as central Kansas. Fragments of export Chinese porcelain were excavated from the ruins of Pecos itself (perhaps brought up from Mexico City as personal belongings of some Spanish settlers). This is just one more reminder of the global reach of culture as early as the seventeenth century.

The last few indigenous inhabitants left Pecos around 1840, their numbers having been reduced from a high of two thousand in the early seventeenth century, to fewer than twenty individuals. They moved nearby, to Jemez Pueblo. In 1999, their descendants reburied the bones of their ancient ancestors, which had been removed during twentieth-century archaeological excavations. In a public procession remarkable for what it conveyed of the fusion, conflict, and overlay of cultures in the American Southwest, the descendants carried two important items deeply emblematic of their historic relationship to their conquerors: the ceremonial cane of authority bestowed upon the native governor of the Pueblo by King Philip III of Spain in 1620, and another staff, which was a gift from President Lincoln in the 1860s. These symbols of power and authority ·were perhaps given in recognition of the recipients' loyalty to a larger system of government. But their Pueblo owners see them as emblems of their long history as a sovereign people and as signifying their coequal relationships with the Spanish and, later, the American newcomers in their land.

The Segesser Hides: A Pictorial Record of Spanish and Pueblo Bravery on the Great Plains in 1720

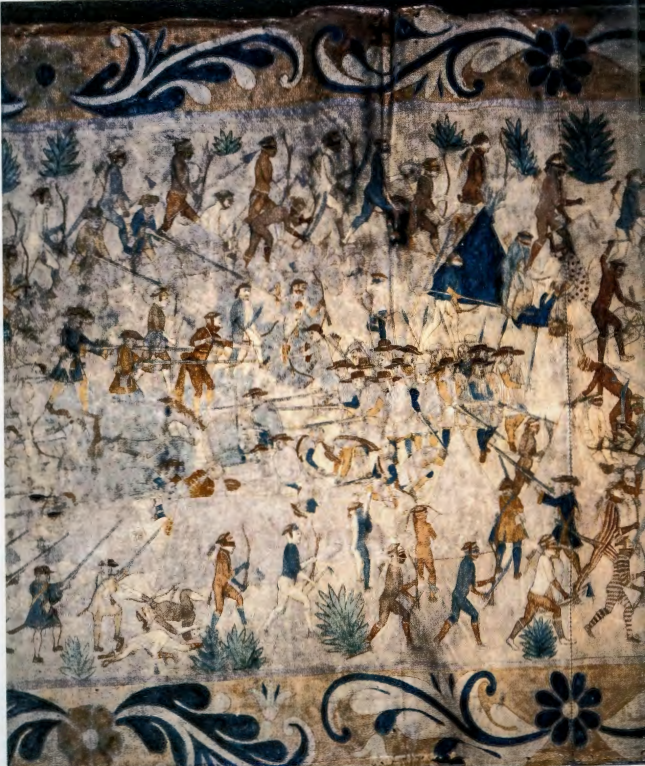

The history of the Southwest is full of narratives of animosity between the Pueblos and the Spanish. Less often told, but eloquently recorded in one visual narrative, is the story of Spanish and Pueblo alliances. An extraordinary hide painting in the Palace of the Governors, in Santa Fe, sheds light on conflicts and alliances in the eighteenth-century West. One of two paintings called the Segesser Hides (after the Swiss family that owned them for more than two centuries), this 17-foot-long panorama is pieced together from buffalo hides (fig. 2.37). Canvas for painting was scarce in Northern New Spain. Native material such as buffalo hide was adapted to make large painted wall coverings like this one, a rough, New World version of the woven pictorial tapestries that adorned the walls of European palaces and great houses. (In Spain, animal skins were sometimes used for wall coverings and altarpieces, another legacy of the Muslim influence there.)

This painting tells the story of an historic event that transpired in 1720, when government officials in the Province of New Mexico became concerned about possible French encroachments into Spanish territory. French explorers and traders had traveled down the Missouri River from Canada onto the Great Plains, and La Salle had explored the Gulf of Mexico. A number of Spanish scouting expeditions traveled onto the Great Plains to look for evidence of French settlement. The expedition recorded in this hide painting was the ill-fated one of Pedro de Villesur. Accompanied by some four-dozen Spanish troops and five-dozen Pueblo Indian auxiliaries, Villesur headed northeast from Santa Fe, through present-day Kansas, as far as eastern Nebraska.

On August 14, 1720, while the troops from New Mexico were sleeping in their tents and tipis near the confluence of the Loup and Platte Rivers (shown realistically in another portion of this long pictorial scene), Pawnee and Oto Indian warriors (the native inhabitants of that region, allies of the French) attacked. Some three-dozen Spaniards, including Villesur himself and Father Juan Minguez, the Franciscan priest who accompanied the expedition, were killed. So was Joseph Naranjo, the Santa Clara Pueblo Indian who led the Native troops, and ten of his men. The rest returned to New Mexico in defeat, having lost all of their trade goods and supplies.

The detail shown here from the center of the 17-footlong scene depicts the Spaniards and their Pueblo allies being overwhelmed by their attackers. On the right is the defensive position of the Spanish camp. A blue painted tipi is shown at center right. Other, unpainted canvas tents, more difficult to discern in this faded painting, encircle the Spanish men, huddled together as they try to defend themselves with muskets and spears. Their Pueblo allies must have been the first line of defense, for a number of them lie dying.

Spanish and Pueblo men all wear sleeveless jackets made of several layers of hide to repel arrows. (The effectiveness of such garments is demonstrated in the lower right of the scene, where two Pueblo soldiers continue to fight, though their garments are riddled with arrows.) The Spanish are distinguished by their wide-brimmed brown hats. The Pueblo men are hatless, their long hair tied in buns at the nape of the neck.

The Frenchmen and their Native allies differ dramatically from each other, as well as from their New Mexican opponents. The French wear blue or brown knee-length coats, tricorne hats, and leggings, while the tall Pawnee and Oto are naked. These vividly painted warriors must have presented a startling sight to their Pueblo opponents, because the artist has taken great pains to convey the individuality of each: one is blue with white legs, another brown with blue legs and forearms; yet another is gray with white spots, and others have red stripes. Many Pawnee and Oto men have horizontal bands of paint on their faces, as well. The Native men fight with bows and arrows, hatchets, swords, and spears; only the white men have firearms.

On the right, some three-dozen figures are spread out over otherwise blank canvas, making this portion of the conflict easier to read than the battle to the left, where in the center of the composition stands the Franciscan, Juan Minguez, holding a cross. He seems intent on blessing the dead and comforting the dying, paying no heed to his own danger. Although he covers his head with the hem of his robe, he has already been struck by an arrow. The artist has made it clear that the Pawnee in pursuit will finish him off presently. Directly in front of him, a Pueblo soldier leads the way into the camp.

Who painted this epic scene? In eighteenth-century Santa Fe, the Spanish employed Pueblo people to manufacture goods such as clothing, wagons, and painted hides for export south to more prosperous markets in New Spain, and there is archival evidence that painted hides like this one were produced by Pueblo artists in workshops there. Following a practice that we know existed in central Mexico, one or two Spanish artists, trained in European techniques, may have overseen scores of Native apprentices. The artist or artists who worked on this painting ( completed sometime between the events of 1720 and 1758, when it was sent to Europe) adapted European conventions of naturalistic detail, foreshortening, overlapping of figures, and a limited use of perspective. The plants are very schematized, but the figures are convincingly rendered. Many are shown in profile, while others turn in space, their bodies depicted with skillful naturalism.

Witnesses' accounts surely contributed to the realism of this battle scene, rendered in a way that evokes the confusion, tumult, and gory detail of hand-to-hand combat. Many of the details are so vivid that it might have been painted by a survivor of the battle, or at least a Pueblo painter who had heard firsthand accounts of the bravery of the Pueblo and Spanish forces when faced with overwhelming odds. Of the sixty Pueblo militia who traveled on this expedition, forty-nine made it home alive; one of them certainly could have worked on this scene. One thing remains a mystery: surviving narrative accounts of this battle do not mention the presence of the French ( easily identified in the hide painting by their blue and red coats, hats, and muskets). Was this painted as a kind of propaganda piece, exaggerating to Spanish government officials the threat of the French to their empire? Or does the image-so accurate in all other respects-shed new light on the details of an early eighteenth-century cultural clash on the Spanish frontier? Indians fought on both sides of the battle depicted here. This reflects not only ancient enmities but shifting modern alliances, as competing European powers jockeyed for control of the North American continent.