6.6: Romanesque (1000 CE – 1150 CE)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

The Romanesque period began in 1000 CE to 1150 CE and grew as the ideas of monasticism expanded, and more people pursued a life of spiritual work. Europe’s art scene was expanding, and art was no longer in the exclusive purview of the ruling class and church hierarchy. A monastic life became essential in the Orthodox and Catholic churches prompting a building boom in churches. Growing numbers of priests, monks, and people on pilgrimages traveled to worship relics sequestered in churches. Romanesque art, located in France, Italy, Britain, and German lands, was influenced by a mix of Roman, Carolingian, and Byzantine concepts.

Churches (6.25) were the center of architectural development and the use of art. The buildings took after the Roman basilica concept with the apse; nave and lateral aisles expanded with side chapels and galleries to walk around in the church. The Romanesque architecture was a fusion of past designs; however, it needed to accommodate all the pilgrims, monks, and priests now pilgrimaging to view the saint's relics. The old timber roofs were replaced by masonry vaulted ceilings.

The use of barrel vaults (6.27), unique to the churches, were painted with religious stories. The barrel vault was a single arched structure designed to hold up the stone ceiling. The walls of the churches were thick, massive, and self-supporting, eliminating the need for any flying buttresses. The walls were so thick and massive there were few windows in the churches, making the building's dark inside.

Frescoes (6.26) dominated the barrel vaults in most churches. The paintings decorated the walls and ceilings with religious icons and stories of the Christian religion, as most Europeans were illiterate. Some of the frescos were embellished by gold leaf, providing light as the candles reflected off the gold.

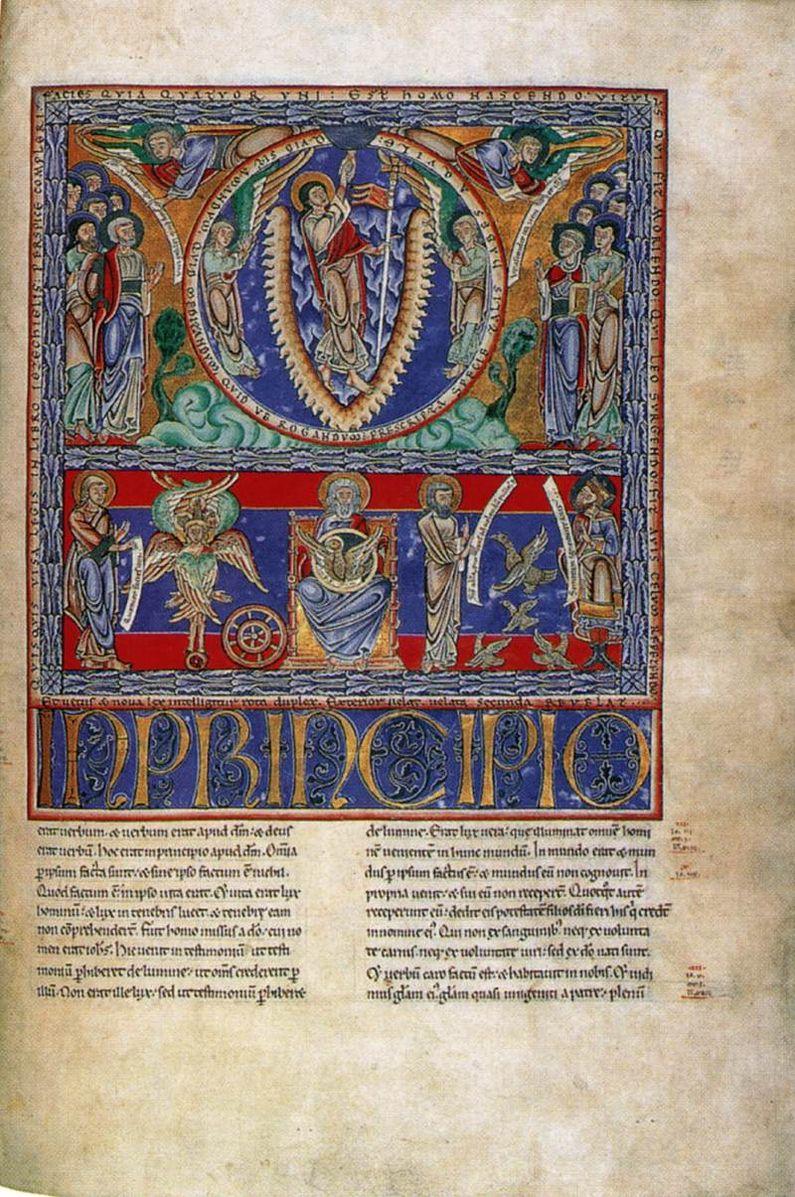

The monasteries were the repositories of information and the illuminated manuscripts became a viable industry in the 11th century. By hand, the monks wrote and illustrated biblical information also copying classical philosophers from Latin and Greek writings and Islamic treatises on mathematics. Glowing illuminations (6.28) used vibrant colors filling the spaces with abstract decorations, the figures abstracted to fit into unusual spaces on the page. The illustrators used parchment made of skin from a sheep, goat or calf, writing the text before adding and images.

The monasteries were the repositories of information, and the illuminated manuscripts became a viable industry in the 11th century. By hand, the monks wrote and illustrated biblical information, also copying classical philosophers from Latin and Greek writings and Islamic treatises on mathematics. Bright illuminations (6.28) used vibrant colors, filling the spaces with abstract decorations; the figures abstracted to fit into unusual spaces on the page. The illustrators used parchment made of skin from a sheep, goat, or calf, writing the text before adding and images.

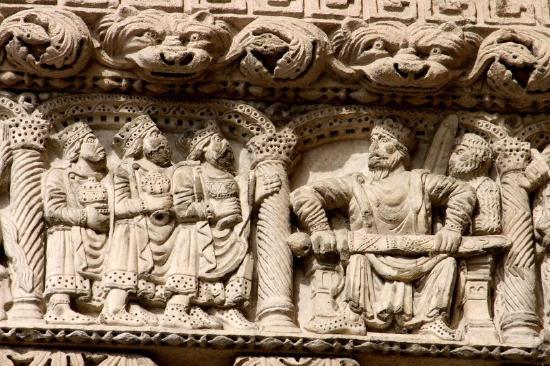

Standalone statues in stone or bronze were seldom used in Romanesque art; instead, the artist carved elaborate relief sculptures used to depict biblical history and stories to install on columns (6.29), doors, altars, walls, or other available surfaces. Natural objects were altered into visionary images with a more abstract linear design that was distorted and stylized. Churches might have extensive schemes and illustrative stories covering a whole façade or across the back of an altar. The central or essential figure of the story was generally centered or oversized as King Herod in the relief (6.30) surrounded by smaller standing people.

The artists in the Romanesque period were excellent weavers and created delicate tapestry. Tapestry is a whole piece of cloth, hand-stitched, or embroidered with linen or wool thread in beautiful scenes. The Bayeux Tapestry (6.31) measures 50 centimeters high by 70 meters long and depicts over fifty different scenes. Some of the scenes include the Battle of Hasting 1066, Halley’s Comet, and the knighting of William the Conqueror, providing a visual representation of his triumphs. The tapestry is almost 900 years old and in rare mint condition. Most tapestries deteriorated over time from the environment, so very few remain today.