9.2: The Road to War in Europe

- Page ID

- 154862

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Italian Invasion of Ethiopia

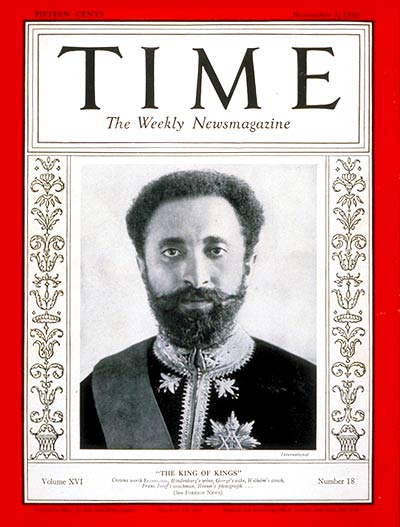

The belief that a nation’s greatness lay in war and conquest was fundamental to the fascist ideology in both Italy and Germany. While Hitler was still consolidating the Nazi regime and rebuilding German armed forces in violation of the Versailles Treaty, Mussolini decided to act. In October 1935, Italy invaded independent Ethiopia from its colonies in Eritrea and Somalia. Italy, like Germany, was not unified until the second half of the nineteenth century. Both Germany and Italy were therefore latecomers to the colonial race in Africa. Ethiopia was one of the only African nations that had not yet been colonized by Europeans. Italians launched an unsuccessful invasion of Ethiopia in 1896. This first attack was repelled with traditional spears and out-of-date guns. However, during the second attack on Ethiopia Italy used tanks, machine guns, air power, and poison gas to secure a sweeping victory. Ethiopia was ruled by Emperor Haile Selassie, and Ethiopia was a member of the League of Nations. Emperor Haile Selassie inspired Rastafari, a cultural and religious movement that viewed him as a messiah for people of African descent. Time Magazine named Emperor Haile Selassie as one of the top 21 political icons in history. Figure 9.2.1 shows the photo of Emperor Haile Selassie on the cover of Time Magazine soon after his coronation in 1930. He is dressed in regal attire, and is wearing a sash. The caption at the bottom of the photo reads "The King of Kings." Ethiopia and Emperor Haile Selassie had a special significance for the Black diaspora. First, Ethiopia was an ancient center of Christianity. Second, the Italian invasion of Ethiopia galvanized Rastas, Africans, and the Black diaspora in their struggles against racism, fascism, and imperialism. Ethiopia and Selassie became symbols of anti-imperial resistance. By April of 1936, the League of Nations failed to respond to the pleas of the exiled Ethiopian king Haile Selassie. Italians engaged in a three-day killing spree in response to an attempted assassination on the Italian viceroy in the conquered capital city of Addis Ababa the following year. At least 20,000 were murdered, including Ethiopian intellectuals who had already been imprisoned after the takeover. As we’ll see, such atrocities were typical of the racism inherent in fascist regimes, who thought that using such terror was the only way to “teach a lesson” to “inferior” conquered peoples.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Photo of Emperor Haile Selassie on the cover of Time Magazine, Time Magazine, in the Public Domain.

Europe in the 1930s

After losing most Latin American colonies in the early nineteenth century, Spain fell into decades of civil war and unrest. Once they lost the Philippines, Cuba and Puerto Rico to the United States in 1898, the Spanish empire was less stable and poorer than several former territories, such as Argentina and Chile. In the early years of the 20th century, many Spanish workers championed the cause of taking down all forms of repression as the pathway to liberate the natural socialist and communal tendencies of humanity. Many found fault with the Catholic Church, which received government funds to educate and provide for the poor, but was seen by the starving, illiterate, landless peasants, and proletarians as ineffective and hypocritically enjoying its riches. By 1931, even the middle class had had enough of Spain’s repressive backwardness. The king abdicated—another victim of the crisis of the Great Depression—and the Spanish Republic was established. A new Spanish constitution formed a presidential-parliamentary government with proportional representation, much like the Weimar Republic in Germany. Agrarian reform and limiting the temporal power of the Catholic Church divided the Spanish people, resulting in the liberals and socialists losing control of the government in 1933. Rebellions in 1934 by radical miners in northern Spain led to repression and the imprisonment of thousands. In response, a competing, alternative government was formed in February 1936, “The Popular Front”.

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin ordered the world’s communist parties to join in supporting the anti-fascist Popular Front coalition of socialist, anarchist, and workers' parties seeking to preserve and extend liberal reforms. However, when the new government rolled out agrarian reforms and began suppressing the Church, street fighting and assassinations led to a fascist-supported military coup orchestrated by General Francisco Franco in July 1936. The “nationalist” Franco regime and the “republican” Popular Front government entered into a bloody civil war. One of the greatest atrocities carried out by Franco took place against the Basque people in the northern town of Guernica - a crime represented below in Pablo Picasso’s canvas by the same name. Hitler and Mussolini immediately sent weapons, troops and air support to Franco, while Stalin supported the Republic. The leading European democracies—Great Britain and France—declared neutrality while the United States chose once again to try to stay out of Europe’s disputes. Individual British, French, and American volunteers arrived to fight for the Republic, hoping to make Spain “the graveyard of fascism”. However, even before Franco and the nationalists finally defeated the Republic in April 1939, Stalin had pulled Soviet advisors out of Spain and abandoned the Popular Front strategy. Francisco Franco remained the authoritarian dictator of Spain until his death in 1975.

The response of World War I victors may seem puzzling. Why not step in and swiftly put an end to the rising threat posed by emerging dictators? By the 1930s, and the Great Depression, the French, British, and Americans were wondering what “winning” the Great War had really meant. The deaths of millions and the wounding of millions more did not seem worth repeating. All the vitriol and propaganda justified to cause such suffering fell flat. On the other hand, the Germans had been humiliated by the peace and were now led by a man and a party, who claimed that they could have won if they had not been “stabbed in the back” by liberals, communists, social democrats, and Jews. Unfortunately, many fascist sympathizers in the democracies agreed with this assessment: that corrupt politicians and capitalists, as part of a Jewish-led cabal, had been the only ones to benefit from leading their countries into a useless war. There was truth in the observation that bankers and capitalists had profited from the war, but there was no evidence of widespread, racial or political conspiracy. The fact that public opinion descended into fantastic conspiracy theories is a testament to the psychological effect of the worldwide economic crisis on a fearful humanity.

Hitler’s foreign policy, which he had announced to the world in his 1925 book Mein Kampf, was based on the idea of absorbing regions with German-speaking populations into his Greater Reich. Lebensraum, living space, for Aryans would be taken from the Slavic peoples of eastern Europe. In March 1938, Germany annexed Austria, its ally in the previous war and homeland of Hitler, with the support of most Austrians (the von Trapp family of Sound of Music fame were the exception, not the rule). This was a direct violation of the anschluss clause in Versailles, and once again, Great Britain and France failed to respond. Hitler next set his sights on the Sudetenland, an ethnically German region of Czechoslovakia. In October 1938, the British and French leaders, alarmed but still anxious to avoid war, attended a diplomatic conference in Munich where they agreed to German annexation in return for a promise to stop all future German aggression. They were desperate to believe the Führer could be appeased, but in March 1939, German troops rolled into the rest of Czechoslovakia. The Czechoslovakian government had not even been invited to the conference in Munich; despite being the only democracy standing in Central Europe by 1938, they were betrayed by the appeasement policy of their fellow democracies in the League of Nations.

Nor were the democracies moved by Nazi excesses against the Jews in Germany. There was great international concern over Germany hosting the 1936 Olympics in Munich, but the Nazi government took down all anti-Semitic propaganda, loosened restrictions and fooled the world with a facade of international peace and prosperity when the international organizations began arriving for the events. In November 1938, after a German diplomat was assassinated by an exiled German Jew in France, the Nazi government allowed a massive outpouring of violence against Jews and Jewish-owned businesses. German mobs murdered dozens of Jews, publicly humiliated thousands, and burned businesses and synagogues in a frenzy of violence that became known as Kristallnacht, “the Night of Broken Glass.” Many people in these democracies were outraged, thinking that such pogroms (state sponsored violence) could not exist in such advanced nations like Germany despite the fact that pogroms against Jewish communities have taken place throughout Europe for thousands of years. Still, no action is taken.

All of this was happening as Stalin supported the Spanish Republic, hoping that the other democratic countries would join in a struggle against rising fascism. When they instead appeased Hitler, Stalin correctly concluded that the capitalists perceived Hitler as a bulwark against the communist Soviet Union rather than as a threat to their own territories and interests. The Soviet Premier changed his diplomatic strategy on August 23, 1939 by signing a Non-Aggression Pact with Germany. By that time, Hitler had set his sights on “liberating” the German-speaking population in Poland, so the two despots devised a plan to divide the nation into two “buffer states”. The world learned of the secret agreement to divide Poland included in the Nazi-Soviet Pact when Stalin sent his armies into eastern Poland three weeks later. This uneasy peace disintegrated just over a year later when German troops poured across the border on September 1, 1939.

The Invasion of Poland

Two days after the German Wehrmacht invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Britain and France declared war and began mobilizing their armies. The war planners hoped the Poles would be able to hold out for three to four months to give the Allies time to prepare an intervention, but Poland fell in three weeks, partly due to the Russian invasion in the east and partly due to a new form of warfare. The German leadership, anxious to avoid the rigid, grinding war of attrition in the trenches of World War I, had built its new army for speed and maneuverability. German strategy emphasized the use of tanks, planes, and motorized infantry to concentrate forces, smash front lines, and wreak havoc behind the enemy’s defenses. It was called Blitzkrieg or “lightning war”, and it was incredibly effective. After conquering eastern Poland, Stalin’s armies shifted focus to occupying the Baltic States of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, and to invading Finland. The Soviet leader was planning to reestablish the borders of the former Tsarist Russian Empire. However, the invasion of Finland met stubborn resistance and a bitter winter, and resulted in small territory losses for the Finns.

The Phony War

Meanwhile, after the fall of Poland, France and Britain braced for the inevitable German attack. In April 1940, the Germans quickly conquered Denmark and Norway in an effort to prevent the British naval blockade which had been so key to their defeat in World War I. The following month, Hitler launched his Blitzkrieg further into Western Europe by invading the Netherlands and Belgium to avoid well-prepared French defenses along the French-German border (The Maginot Line). Poland had fallen in three weeks; France lasted only a few weeks more. By June, Hitler was posing for photographs in front of the Eiffel Tower. In another propaganda victory, Hitler made the French diplomats sign their surrender in the same railroad car used for the German surrender in the First World War.

The Vichy Regime in France

Germany split France in half, occupying the north and allowing a collaborationist government to form in Vichy to administer the south and the French colonies. Led by the “Hero of Verdun,” Marshal Philippe Petain, the Vichy regime sought to reorganize France along authoritarian fascist lines. Significant support for Germany by the French right was one of the reasons for their defeat in June 1940. Many in France had also abandoned democracy and welcomed the demise of the Third Republic. They reasoned that if the future held a German-dominated Europe, it would be better for France to collaborate as partners rather than as subjects in a new Nazi empire. Although this rationalization fit into the scheme proposed by German propaganda, Hitler would never allow a full partnership with any of his conquered peoples.

The Battle of Britain

With France under control, Hitler turned to Britain, the last free democracy of Europe. Operation Sea Lion, the planned German invasion of the British Isles, required air superiority over the English Channel and would necessitate an amphibious landing of massive proportions. From June until October 1940, the German Luftwaffe fought the Royal Air Force for control of the skies. Despite having fewer planes, British pilots won the so-called Battle of Britain, saving the islands from invasion and prompting the new prime minister, Winston Churchill, to declare, “Never before in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few.”

However, if Britain was safe from invasion, it was not immune from ongoing air attacks. Frustrated by losing the Battle of Britain, Hitler began a bombing campaign against cities and civilians. The Blitz, as the British came to know the nightly bombing raids on London, killed at least 40,000 civilians. Population centers like Bristol, Cardiff, Portsmouth, Plymouth, Southampton and industrial cities like Swansea, Belfast, Birmingham, Coventry, Glasgow, Manchester, and Sheffield were also targeted for heavy bombing. The Royal Air Force defended the cities as well as they could, people slept in the Underground subway tunnels for protection at night, and British industrial production continued after being moved out of major cities. The British people, encouraged by Churchill, kept calm and carried on.

In anger, Hitler and his Vice Chancellor Herman Göring began a policy of striking London every day in an effort to break the will of their enemy. Beginning on September 7, 1940, London was bombed every night for 56 days, including a large daylight attack on September 15. British morale failed to break, and Germany eventually shifted to targeting Atlantic shipping and bombing port cities to starve the enemy. When the port of Clydebank in Scotland was bombed in March 1941, only 7 of 12,000 buildings escaped damage. But the Germans failed to gain complete air superiority, partly due to the British deployment of RADAR (Radio Detection and Ranging). The technology had been developed in the 1930s and was advanced and finally perfected by Britain in the early 1940s. It would be offered to the Americans in exchange for financial and industrial support as the two nations strengthened ties to “defend democracy” even before official U.S. involvement in the war.

Operation Barbarossa and German Lebensraum

Nazi ideology considered the English as close to racial equals, and Hitler hoped that Great Britain would eventually join a crusade against Bolshevism. However, Nazi doctrine focused on establishing German lebensraum in Eastern Europe, enslaving the lesser Slavic peoples to work for the Aryans. In order to break with the Soviet pact German armies invaded the Balkans and set up puppet regimes in Hungary and Romania, giving them a wider front for attacking the Soviets. Mussolini sent his troops from Albanian (conquered in 1939) to conquer Greece. The Greeks not only defended themselves but pushed the Italians back into Albania, forcing Hitler to bail out Mussolini by invading Yugoslavia and Greece.

In June 1941, German forces crossed into the Soviet Union in a massive surprise attack. “Operation Barbarossa” was the largest land invasion in human history, fought over a 1,800 mile front between 10,000,000 combatants. France and Poland had fallen in weeks, and Germany hoped to use the same Blitzkrieg tactics to break the USSR before the winter. Initially this plan succeeded in catching Stalin’s Red Army unprepared, quickly conquering enormous swaths of land and nearly three million prisoners. The sheer size of the assault, the distance of supply lines, and a late start in the year result in significant slowdowns after 4 or 5 months. After recovering from the initial shock of the German invasion, Stalin moved his factories east of the Urals, out of range of the Luftwaffe. He ordered his retreating army to adopt a scorched earth policy, destroying food, rails, and shelters to slow the advancing German army.

Germany had won massive gains, but the winter found troops exhausted and overextended eventually split into three main forces. Northern army group reached Leningrad and waged an 827-day siege where over 1,000,000 Soviets starved to death. Center group came within 60 miles of Moscow, but Stalin refused to evacuate women and children, and instead ordered every single citizen to dig anti-tank ditches with their bare hands if tools were unavailable. The refusal to retreat created a sense of unity and desperation. This combined with the brutal Russian winter and German supply lines thousands of miles long left the Nazis faltering, and ever naturally falling back after a three-month battle that killed a million people. The third army group to the South will face off in what proves to be the most decisive battle of the entire war: The Battle of Stalingrad.

- How did Hitler surprise Stalin with Operation Barbarossa?

- Why was the Blitzkrieg strategy unsuccessful in Russia?

- What were the main causes of World War II?

- How did racism play an early role in fascist expansionism?

- Why did Stalin support the Spanish Popular Front?

- Why did the European democracies try to appease Hitler?

- Was Stalin wrong to sign a non-aggression pact with Germany?