6.2: The British Commonwealth and the Spread of the British Empire

- Page ID

- 154835

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

The British Commonwealth: Canada, Australia, and New Zealand

While the British North American colonies achieved independence and became the new nation of the United States, British control of Canada and islands in the Caribbean was retained. The French-speaking Quebecois and the British in Ontario found common cause and allied together against the United States in 1775 and 1812. After the War of 1812, the European population of Canada increased exponentially. This had negative ramifications for the indigenous peoples in terms of disease, warfare, displacement, and state control over their lives.

With the British North America Act of 1867, Canada became a self governing nation within the British empire. This new Dominion of Canada combined Quebec, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and New Brunswick with John A. MacDonald as the nation’s first Prime Minister. MacDonald negotiated the purchase of the Northwest Territories from the Hudson’s Bay company in 1869, and convinced the people of Manitoba, Prince Edward Island, and British Columbia to join the Dominion of Canada.

MacDonald realized that Canada’s western and eastern coastal regions needed a transcontinental railroad to bind them together. Construction started in 1881 and by 1885, the Canadian Pacific Railroad was completed. The C.P. Railroad operates just north of the border with the U.S. (see Figure 6.2.1). Several lines from Canada connected to U.S. cities such as Minneapolis, Milwaukee, Detroit, and Chicago. Even today, 90% of Canada’s population lives within 100 miles of the U.S. border. Figure 6.2.1 shows the extensive network of railroads that united Canadians from coast to coast. Several hotels and were built along the railroads to encourage travel and tourism. Canadian Pacific Railway is one of Canada's most influential corporations. It is still one of the most effective transport systems for the Canadian economy.

Between 1788 and 1859, the British created six colonies in Australia, which they settled with convicts. Most of the crimes were petty or related to debt, while some were political, such as Irish protest of English rule. The British also annexed New Zealand in 1840, assisted by a joint stock company called the New Zealand Company.

In both Australia and New Zealand, native peoples lost land in much the same manner as in British North America. In Australia, the vast continent allowed aborigines to retreat, until environmental and other factors brought them into increasing contact with the settlers and their descendants. In New Zealand, relations between the native Maori and the settlers followed a pattern similar to those of the western United States: treaties made, treaties broken, wars fought and won by the settlers, who took more land. Figure 6.2.2 is an oil painting of Maori woman in traditional dress in 1890. She is wearing a hei-tiki around her neck, earrings, and two huia feathers in her hair. She has a moko design on her chin. Before the arrival of Europeans Maori women played an active role in their society and could inherit property. However, European imperialism created gender inequalities among the Maori. Respect and celebration of some Maori rights and culture have become integral to New Zealand identity in recent decades.

British India and the Beginning of the Independence Movement

When the British East India Company began its conquest of India in the early seventeenth century, the Mughal Empire was at its height and its emperors were wealthier than all the European monarchs combined. During the eighteenth century, India was still the world's largest producer of cotton, especially in the region of Bengal. Mughal art, architecture and science flourished and these legacies are still widely appreciated today. Figure 6.2.3 shows three of the most important Mughal emperors, namely Akbar, Jehangir, and Shah Jahan, sitting regally on their ornamented thrones. Below them is an opulent carpet and the emperors' ministers stand deferentially ready to explain documents related to imperial administration. The painting in Figure 6.2.3 was made for emperor Shah Jahan during the seventeenth century to illustrate the dynasty's lineage. Akbar is seated in the center and Shah Jahan is seated to his right and is receiving the emblem of imperial authority from his grandfather, Akbar. Shah Jahan's father, Jahangir, is seated to the left of Akbar.

Gradually, the Mughal’s reign began to weaken as the EIC encroached politically and militarily on its territory. The EIC expanded its trading activities, and slowly took over regional principalities, splitting them off from Mughal control. By the middle of the 19th century, the EIC controlled most of modern day India, Pakistan, Burma, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. The EIC began shifting away from simply trading, and began reorganizing the Indian economy, clearing forests, and establishing the widespread cultivation of tea, coffee, and cotton. The EIC developed the cultivation of opium in India in order to smuggle it into Qing Dynasty China, though it was illegal in both Britan and China.

The British Crown took over direct control of the colony in 1858 after an uprising called the Sepoy Mutiny. The people of India were coerced to produce agricultural products for the metropole, and the country’s raw materials were extracted to provide for Britain’s growing industrial economy. Once products were manufactured in Britain using raw materials from the colony, Indians, in turn, were made to purchase these mass-produced textiles and other goods from British factories as a “captive market.” Likewise, railways were constructed in India to facilitate the movement of goods and resources and to help facilitate imperial expansion rather than to develop and enhance the lives of the colonized populations of India. This economic system geared toward British economic profitability was attractive to other European empires, influencing, as discussed below, a scramble for colonies in Africa in the late nineteenth century. As can be imagined, this system was not attractive to Indians who wished for a better life in an independent India.

There were "princely states" within British India that were nominally independent, though they still were subject to supervision and control by British authorities. Newer research delves into the internal developments and uniqueness of the princely states and the resistance to British rule that they were able to weave into their societies. Figure 6.2.4 shows a 1909 map of India with British territories in shades of pink and the princely states in shades of yellow. The map was produced by the Imperial Gazetteer of India.

By the 1850s, the British had established schools to instruct the local Indian elite in English, engineering, science, and British imperial law. Initially, training and educating Indians began with the formation of army and police forces commanded by British officers. Later this training included local administrators who spoke English and applied British imperial laws.

Some Indians worked in British colonies in Africa, where they operated railways and the postal service. Some worked as carpenters and bricklayers constructing government offices and private homes for the new colonial political and commercial elites. Indian shopkeepers played an enormous role in the local economies of these colonies into the 20th century. Some Indians migrated to Great Britain’s territories in the Caribbean as indentured servants. In Guyana, South America, over 40% of the population is of Indian descent today.

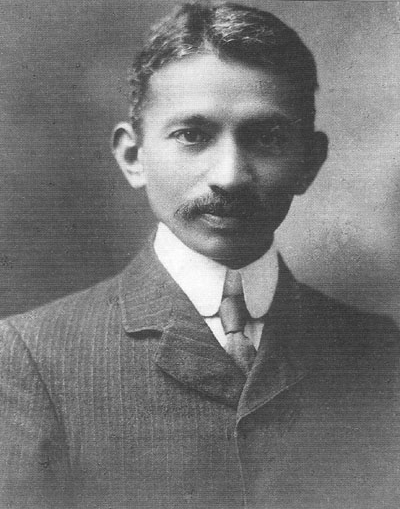

Mohandas K. Gandhi is an example of someone who was trained to work for the British colonial regime. Figure 6.2.5 is a black and white portrait photo taken in 1909 of M.K. Gandhi in a western style suit and tie. After attending a British school in India, Gandhi went to London and studied law. Upon graduating, he went to South Africa and practiced law for twenty-five years before advocating for Indian independence. In India his admirers called him Mahatma, which means the "great soul" in Sanskrit, as an expression of his wisdom and courage.

The path taken by Gandhi was duplicated in other European colonies. Educated local elites and professionals also began to demand greater autonomy and political rights. Their education provided them with the means to study their own histories, religions, and cultures. They found a sense of pride and identity in these studies, leveled sophisticated critiques of their colonizers, and articulated a collective desire for independence from colonial rule.

- What was the status of Canada with the passage of the British North America Act of 1867?

- What is a "captive market" and how did this work in India?