4.3: Atlantic Revolutions

- Page ID

- 154818

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Introduction

This section focuses mostly on revolutions involving freed individuals against either a colonial ruling structure or an oppressive national government. These revolutions, while impactful, involved the descendants of the original European explorers and colonizers, or their own countrymen, as opposed to the marginalized populations that originally occupied the area or were brought in for forced labor. A separate section in this chapter on a particular revolution – one that would inspire others in similar situations to take action – will cover the push-back of oppressed enslaved people and indigenous peoples against their oppressors, and what effect that had on the slave-owning world.

American Revolutionary War

The first English explorers arrived on the North American continent at a couple of different points in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. These explorers would encounter the indigenous populations who occupied the various areas along the eastern seaboard of North America, labeling them “savages” and “barbarians”. Although some English colonizers would attempt to convert to Christianity the local populations, as well as pushing them into forced servitude, most dismissed the natives as unworthy of anything but exploitation, as outlined in the first chapter. Instead, these settlers would rely on indentured servants to take on the labor needed to grow the colonies. Eventually, the indentured servant program would die out, replaced by African slaves brought through the triangular trading system. While England itself claimed to abhor slavery, they were certainly aware of it, as it continued to perpetuate the mercantilist economic system that allowed the colonies to enrich the mother country.

England’s colonies experienced a number of different types of government oversight during the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The early forms under the Stuart kings and queens involved more commercial engagement, such as the Virginia Company, founded in 1606 with the support of King James I of England (VI of Scotland). But England would face their own internal conflict with the English Civil War lasting from 1642 to 1651. The king, Charles I, attempted to force the Church of England created by the English king and Queen Elizabeth’s father Henry VIII onto Calvinist Scotland. This resulted in a revolt against the king’s authority in that region. Charles then turned to Parliament to demand the money to pay to defend that authority, and Parliament denied him. In anger, Charles dissolved Parliament, effectively robbing those in Parliament of any authority over the governing of England, and took the money for himself. This resulted in fighting between the authority of the English crown and that of Parliament, with those supporting the monarchy called Royalists and those supporting Parliament called Parliamentarians. The British colonies on the American continents attempted to remain neutral, but in many ways the war found its way over, forcing certain colonies, such as Virginia, to take sides. The war would end with the execution of Charles I (see Figure 4.3.1), much to the dismay and disgust of other European powers. One Flemish artist, John Weesop, refused to return to England after painting the king’s execution because he couldn’t stomach being in a place where they chopped off a monarch’s head. Figure 4.3.1 is a contemporary German print that depicts the execution of Charles I outside the Banqueting House. The engraving shows a large crowd of men and women gathered to witness the execution. The executioner is holding the severed head of the king while standing next to the still bleeding body.

Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector of England with the execution of Charles I. A Puritan Parliamentarian, Cromwell rose to power as a result of English distrust and disenchantment with the monarchy overall. However, during his “reign”, Cromwell became synonymous with oppression, particularly in another English territory, Ireland. Cromwell’s plantation system in Ireland, where he “planted” Protestants, particularly Puritans, became the model for the plantation system used in the American colonies and which continued the practice of race-based slavery in the southern region of what would become the United States. He and Parliament also created an economic embargo of goods from colonies that sided with the dead king’s son, Charles II, which was followed up by the Navigation Acts, aiming to prevent any circumvention of the embargo by forcing all goods to be shipped on English ships only. While it reestablished Parliamentary authority over their colonies, it allowed resentment of this treatment to fester.

In addition, Cromwell’s religious intolerance toward anyone who wasn’t a strict Puritan alienated him from some of the British population and would drive them to seek refuge in the American colonies. As he had outlawed both the Church of England (Anglican) and the Catholic religions, people who adhered to these faiths founded new colonies, such as that of Maryland, a Catholic refuge. Cromwell attempted to pass the Lord Protectorship on to his son, but the son was too weak to hold it, and after Cromwell’s tenure, many English people desired a return to what they knew; a monarchy.

The end of the Cromwell protectorship brought the return of the Stuart line of royalty to England in the form of Charles II, whose reign was peaceful and reasonably uneventful; both Britain and their colonies continued growing. Charles would die childless, so his crown would pass to his brother, James II. James had been raised Catholic, and although his daughters, Mary and Anne, would follow the Protestant church, James eventually had a son he threatened to raise in the Catholic faith, meaning his heir would bring the country back to Catholicism. Many feared another religious war, and so forced James to abdicate the throne in favor of his eldest daughter Mary and her Protestant husband, William of Orange.

William and Mary’s arrival in England to start their reign in 1688 was deemed a “Glorious Revolution,” called so because of the lack of bloodshed surrounding the transfer of power from father to daughter. Parliament also gained a significant amount of power during this time, establishing itself as a separate and equal power to the throne, which remains today. This would become one of the “checks and balances” systems that would inspire the United States government formation, which in turn would inspire other democratic leadership styles. England also saw the creation of a bill of rights in 1689, improving on the rights outlined in the Magna Carta document of the thirteenth century.

William and Mary’s reign would also allow a unique experience in the colonies as well. During this time, neither monarchy nor parliament forced any significant laws or regulations on their American colonies, instead allowing a period of “salutary neglect,” an opportunity for the colonies to simply produce raw materials for Britain to finish and sell to the rest of Europe as well as back to their colonies. In addition, it allowed colonies to attract tradesmen and artisans to create new goods and help grow the colonial economy. This period had a dangerous side effect, though; the American colonies realized that they were capable of self government and that the taxes paid to Britain weren’t necessary. Nor were they necessarily directly benefiting the American colonists, especially since those colonists had little to no representation within either the monarchy and nobility or Parliament.

A number of issues arose within the colonies forcing more British intervention. Conflicts between colonists and local indigenous populations, such as the Pequot War, the Mystic massacre, King Philip’s War, the Susquehannock War, Bacon’s Rebellion, and the Pueblo Revolt, showed Britain the vulnerability of their colonies, especially under self-government. Bacon’s rebellion was particularly harsh, as it not only involved colonists and the local indigenous peoples but led to the colonial governor’s arrest and imprisonment at the hands of colonists. But it would be wars in Europe that expanded into their American colonies that would become the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. For thirty-seven of the eighty-seven years between the Glorious Revolution and the American Revolution, Britain had been at war with other European powers, mainly France, much of which took place on the American continent. In 1754, tensions between the French Catholic and British Protestant colonies erupted into what would become known as the Seven Years' War, or the French and Indian War. This led to further economic pressure on Britain's colonies on the American continent.

The Seven Years' War (1756-63) had been an expensive drain on Britain’s treasury, and Parliament believed the American colonists ought to pay their fair share of the cost of their defense. Britain instituted a number of taxes including the Sugar Act (1764), the Stamp Act (1765), the Townshend Act (1767), and the Tea Act (1773). Boycotts and protests by the colonists soon began, including the famous Boston Tea Party in 1773, during which enraged patriots boarded a British cargo ship and dumped tea from India into Boston harbor, rather than pay the hated new tax.

Although the colonists found these taxes oppressive and obnoxious, to a great extent they were luxury taxes or excises on trade rather than direct taxes on personal income. Still, imposing new taxes on the colonists was a miscalculation by Parliament because the merchants and the wealthy most affected by the taxes had the means and the motivation to organize a resistance movement. And they did.

American colonists also objected to the Quartering Act (1765) that forced them to provide housing and food for British troops. Again, this may have seemed fair to the legislators back in London who had sent an army to defend the colonies against the French and Indians in the recently concluded war; this was the reason given for this act specifically. But it was a big expense for the Americans and was an issue that cut across class boundaries more than the luxury taxes and unified opposition.

Another major cause of American resentment against the British after the Seven Years' War was the Royal Proclamation of 1763 which established a western boundary to the colonies roughly along the ridgeline of the Appalachian Mountains. The support of Native Americans from the trans-Appalachian region had been critically important to the British war effort in North America. Tribes such as the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) were powerful allies, and their leaders complained about the increasing numbers of settlers leaving the coastal colonies to make farms in places like upstate New York, western Pennsylvania, and the Ohio River Valley. The British created an Indian Reserve beyond the Appalachians, including western Virginia and Pennsylvania west of Pittsburgh, which had been a French fort captured in the war. This angered both colonists who looked west for new lands to settle and land speculators who had planned on getting rich by buying and selling the western territory.

In addition to the famous “all men are created equal” and “consent of the governed” parts of the colonists’ Declaration of Independence, the 1776 document included a laundry list of complaints against the British Crown including the charge that the king had “endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions,” meaning the indigenous populations already living in places where colonists wished to expand. The founders understood that independence would mean taking land from these indigenous peoples, using the excuse of “savagery” by the tribes attempting to protect their territories to justify this action. Although the Declaration echoed the Enlightenment ideals of contractual government and representation, at the time these ideals only applied to white male landowners, and certainly not to the indigenous populations already occupying the space.

Enslaved People, American Indigenous, and the Revolution

Often when referring to people forced to labor under race-based slavery, the term "slaves" is used, which does an injustice to the flesh and blood people who found themselves forced into this brutal situation. We need to recognize the humanity behind the term, especially since this forced labor of a group of human beings because of their skin color defined race relationships not only in what would become the United States - leading to a civil war - but throughout the rest of the world as well. This description, along with the use of the term "enslaved people," is included to remind us of the human beings within these roles and that enslaved people caught within the system of race-based slavery were also human beings.

Becoming aware of this through sympathetic colonists, many of the indigenous peoples sided with Britain in the American Revolution because they saw a British victory as their only chance to prevent the colonists from overrunning them. Having seen the power of the British military during the Seven Years’ War, as well as their support after Pontiac’s War, many of the tribes living in the Ohio River valley, whose land had been protected through the Royal Proclamation of 1763, saw more benefit to backing the British than siding with the colonists who had grown discontented with the proclamation forbidding them from expanding out onto indigenous land. Other tribes, particularly in the northeastern region and on the border of what is now Canada, decided not to fight on either side, rather only taking a defensive position to keep the lands they had already been pushed to. Very few tribes ended up fighting on behalf of the colonists; those that did appeared to do so because of their established relationships with certain colonists or because of the changing tide of the war away from the British.

Many slaves also ran away to join British forces, especially after they were offered immediate emancipation by several British leaders, including Lord Dunmore. Though only about five hundred to a thousand enslaved people joined Lord Dunmore’s “Ethiopian regiment,” thousands more flocked to the British later in the war, risking capture and punishment for a chance at freedom. Formerly enslaved people occasionally fought, but primarily served in companies called Black Pioneers as laborers, skilled workers, and spies. British motives for offering freedom were practical rather than humanitarian, but the proclamation was the first mass emancipation of enslaved people in American history. Enslaved people could now choose to run and risk their lives for possible freedom with the British army or hope that the United States would live up to its ideals of liberty.

Dunmore’s proclamation unnerved white southerners already suspicious of rising antislavery sentiments in the mother country. Four years earlier, English courts dealt a serious blow to slavery in the empire. In Somerset v Stewart, James Somerset sued for his freedom, and the court not only granted it but also undercut the very legality of slavery on the British mainland. Somerset and now Dunmore began to convince some enslavers that a new independent nation might offer a surer protection for slavery. Indeed, the proclamation laid the groundwork for the very unrest that loyal Southerners had hoped to avoid. Consequently, enslavers often used violence to prevent their enslaved laborers from joining the British or rising against them. Virginia enacted regulations to prevent freedom-seeking, threatening to ship rebellious enslaved people to the West Indies or execute them. Many enslavers transported their enslaved people inland, away from the coastal temptation to join the British armies, sometimes separating families in the process.

Taking Sides

Not everyone agreed with the idea of separating from Britain, and until towards the end of the Revolution when the French arrived to support the colonists, the population was divided into three different groups. The first group called themselves Patriots; these folks were responsible for the majority of the rebellion against British authority in the colonies. They felt they could govern themselves more effectively than the British government since they had been from the period of salutary neglect discussed earlier in this chapter. To the Patriots, Britain represented an oppressive power that Enlightenment philosophers such as John Locke and Thomas Paine had rejected in favor of the concept of democracy and representation by and for the people. Patriots felt the British Parliament lacked any colonial representation and the only way to overcome this oppression was to declare their freedom from Britain.

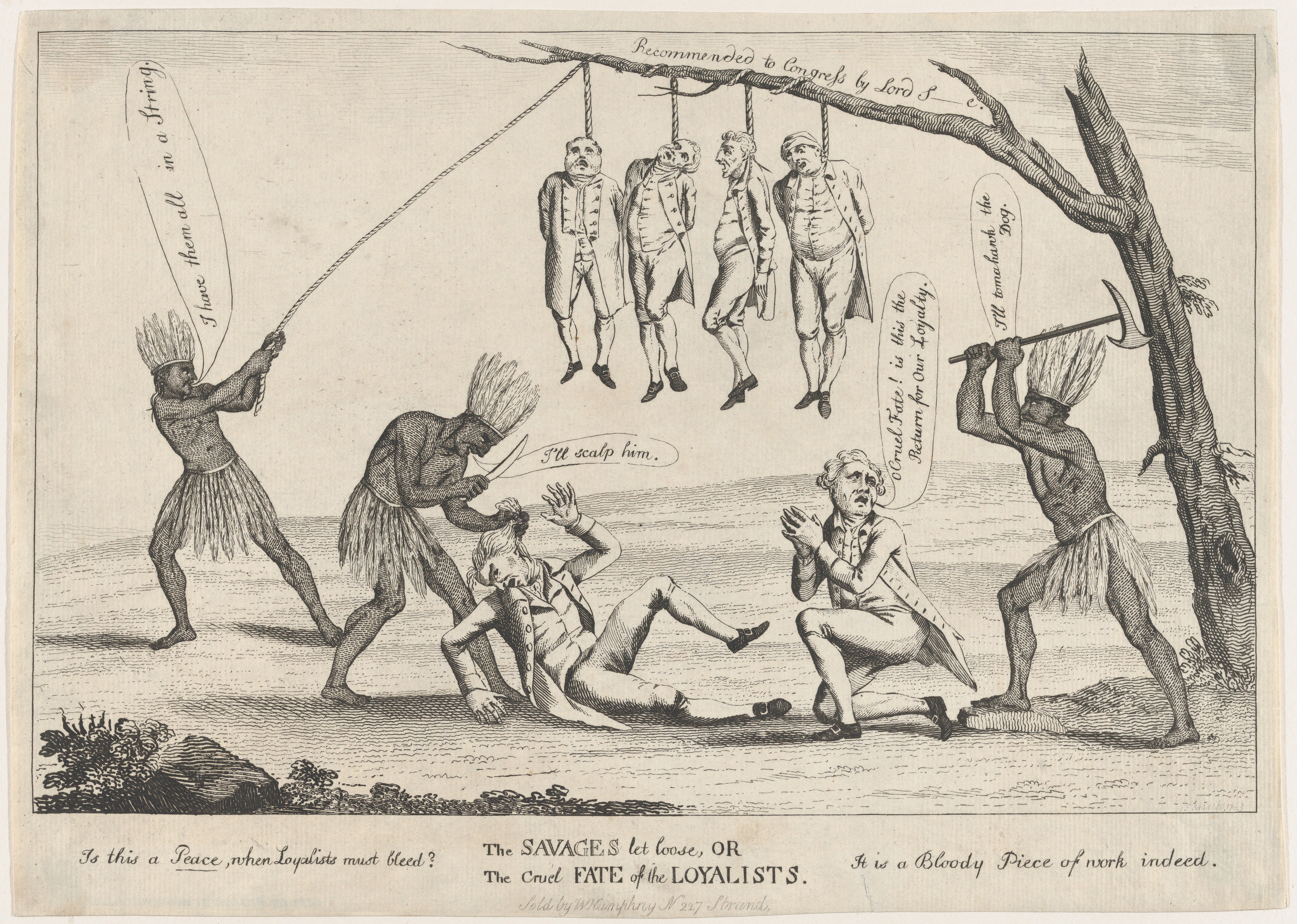

The second group became known as Loyalists due to their continued loyalty to Britain and the crown. Loyalists considered themselves British citizens, and while they may not have agreed with Parliament’s taxes, there were other, legal ways to address their concerns. Historians have estimated the number of loyalists at 15-20% of the total colonial population, or about 400,000 people. Most of these loyalists stayed and became U.S. citizens after the war, but about 70,000 left for other parts of the British empire due to the severe backlash by patriots against those known with loyalist tendencies. Many of those in the north went to Canada and settled New Brunswick while southerners went to Florida, which had remained loyal under British rule, or to the British islands in the Caribbean. Figure 4.3.2 is a satirical cartoon from 1783 by William Humphrey, an English engraver. This etching shows three Native Americans killing six loyalists, and it captures the indigenous sentiments of the 1783 Peace of Paris. The 1783 treaties that ended the American Revolutionary War recognized the territorial claims of the US, but did not mention, let alone recognize, the territorial rights of Native Americans. One Native American seizes by the hair a loyalist lying on the ground, and holds up a knife saying, "I'll scalp him". Another Native American (shown on the right) raises a tomahawk in both hands above a loyalist who kneels on one knee, saying "I'll tomahawk the dog." The third Native American (shown on the left) is holding the noose rope by which four loyalists are hanging from a tree branch, saying "I have them all in a string." Beneath the design is engraved: "Is this a Peace, when Loyalists must bleed?"

The third group had no official name, but rather simply decided not to join one specific side. This group encompassed much of the population, particularly at the early stages of the war. Reasons for remaining neutral ranged from not feeling strongly one way or the other to still feeling the effects of the Seven Years’ War, which had still been fought within 15 years of the Declaration of Independence, and remembered that much like the Seven Years’ War, this would be a conflict fought in their backyards.

These divisions found their way into general society, separating families and friends with different beliefs about what was happening, making the American Revolution a civil war as well. An example of this can be found in one of the American “Founding Fathers” own family. Benjamin Franklin’s son William remained a staunch Loyalist throughout the war, causing a rift between father and son that would never be healed in either of their lifetimes. The Franklin family wasn’t the only family to split over these ideals and the war. A number of people would find themselves on opposite sides of the war as it continued.

After the Revolution, poor Americans were often left wondering what they had fought for. Taxes were high and farmers couldn’t pay them because the “Continental” currency printed by the rebel government to pay the troops was worthless. Western Massachusetts farmers who felt the new government in Boston did not represent them revolted in 1786 in Shays’s Rebellion, which was put down by government troops. This fight and others forced leaders of the Confederated states to reconsider how a federal government should be organized, and they called a Constitutional Convention to meet in Philadelphia, with the Thirteen States sending representatives.

The United States Constitution that formed the new government began with the words “We the People.” It acknowledged the Enlightenment concept that political power comes from the consent of the governed. The final document was influenced by the framers’ studies of earlier republics and by negotiations over various state constitutions that had favored the idea of three branches of government, the legislative, executive, and judicial, along with a system of checks and balances that made no one branch superior to the others. For instance, the President could veto laws passed by Congress, while Congress could, with a 2/3 majority, override the veto. And the Supreme Court could interpret a law as being unconstitutional, checking both the President and Congress.

In spite of these checks and balances, when the Constitutional Convention sent the newly drafted US Constitution to all the states for ratification, many New England towns either rejected the document outright or provisionally approved it with modifications they sent back to the authorities. In most cases, their provisional approvals were marked as simple YES votes and the carefully worked-out modifications were “filed”. But dissatisfaction with the original Constitution was so strong, in spite of the series of promotional articles published about it that has become known as the Federalist Papers, that the convention was forced to write the first 10 Amendments (the Bill of Rights) and issue them at the same time. Without the Bill of Rights, the Constitution would be a much different document.

The French Revolution

This revolution has a more unique quality to it than the others talked about earlier in this chapter, as it was not a colonial independence movement, but a rejection of an existing monarchy by the people of France. There was a much greater degree of participation by poor people in France in this process, and the social changes attempted by the new government were much more significant than simply replacing a British ruling class with an American one as the revolution had done in the new United States. This is where we truly see the end of Absolutism in France, although it had been crumbling for years. Debt problems stemming from the Seven Years' War and French support for the independence of the United States forced King Louis XVI to call the Estates-General in 1789, in order to raise revenue. The Estates-General had not been called since 1614, and its meeting was immediately seen as an opportunity to create a new parliamentary monarchy.

The three “estates”, commoners, nobility, and clergy, traditionally were supposed to have the same power and representation, but it was not much compared to the absolute monarch, particularly under the “Sun King,” Louis XIV, described in Chapter 3. In 1789, the commoners were dominated by educated merchants and large landowners who advocated for establishing a British-style parliament as a check on the King’s power. The commoners had enough support from sectors of the clergy and nobility to declare themselves as the National Assembly, which set about forming a new government.

Dissatisfaction with the current government and excitement over establishing a new one inspired the people of Paris to form militia groups to defend the National Assembly from royalist attacks. On July fourteenth, 1789, these militias dramatically took over the Bastille, a royal prison that held political dissidents. In August the National Assembly agreed to a Declaration of the Rights of Man which claimed “Natural Law” as the basis for equal rights for all and called for liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression. Like the U.S. Declaration of Independence and Constitution, the Assembly declared the “nation” was sovereign, rather than the king, and asserted the rights of freedom of speech, the press, religion, and assembly.

Unfortunately, the power vacuum created by the complete elimination of the prior government structure resulted in the rise of a radical Jacobin Party led by Maximillian Robespierre. By 1793, Robespierre held what amounted to sham trials designed to undermine the authority of the ruling class and give the common folk an opportunity to express their despair and anger physically, which they did wholeheartedly. Known as the Reign of Terror, Robespierre and his cronies imprisoned 300,000 people and executed 40,000, including King Louis XVI and his Queen, Marie Antoinette (see Figure 4.3.3). Many members of the French court were also caught and executed, along with anyone who appeared to be sympathetic to the fate of the French royalty. It brought about a new device as well, the guillotine, which was supposed to make beheading easier and quick. The guillotine would be used all the way up until 1977, after which the French would outlaw the death penalty. Figure 4.3.3 depicts the public beheading of Marie Antoinette by guillotine on a raised wooden platform. Marie Antoinette was dressed in a plain white dress and her hands were tied behind her back. One man on the raised platform is facing the crowd and displaying her severed head while another man is placing a large container under the neck of her bleeding body to contain the spewing blood.

One of the prisoners who just barely escaped with his life was Thomas Paine, the author of Common Sense, who had been welcomed as an honorary citizen of the new French Republic and had even been given a seat in their new legislative assembly. Although he had defended the French Revolution against British criticism in his book The Rights of Man, Paine was imprisoned for objecting to the execution of the French King and Queen. Paine was scheduled for execution but was passed over in a lucky oversight. Other reformers like French feminist Olympe de Gouges were not so fortunate and were killed by the revolution they had supported.

The actions taken by the leaders during the Reign of Terror led to a rejection of the Jacobin party and the trial and execution of Robespierre in 1794. A more conservative government, the Directory, was installed but it failed to manage an orderly transition from the old regime to a new style of republican government. The Directory’s failure created an opening for an ambitious opportunist named Napoleon Bonaparte. A general of the French Army, he had defended the Directory and the new French Republic against the neighboring monarchies, which had sent in troops to put down the Revolution. Returning from an Egyptian campaign in 1799, Napoleon overthrew the Directory and like Julius Caesar established a 3-man Consul style government—but unlike Caesar, he quickly became the sole leader. Napoleon crowned himself Emperor in 1802.

One advantage Napoleon had establishing his empire, in addition to his effective use of the French army, was that he was able to reinstate many members of the old nobility who had been discredited or even imprisoned by the Revolution. He even allowed aristocrats to reclaim some of the property the revolutionaries had taken from them. Napoleon also introduced a new Civil Code in 1804 that completely revamped the French legal system and is still in use today. The Code, designed by a panel of four eminent judges, replaced France’s old feudal legal system and has been tremendously influential in Europe and elsewhere in the world as nations developed modern legal systems.

In a series of wars between 1804 and 1807, Napoleon extended French control to much of Germany, Italy, Spain, and the duchy of Warsaw, and built strong alliances with Austria and Prussia. At its height, the French Empire ruled over 70 million subjects, and to secure its most profitable colony Napoleon sent 40,000 troops across the Atlantic to Hispaniola to try to retake San Dominique from an army of former slaves led by Toussaint l’Ouverture. This would become known as the Haitian Revolution, which will be discussed in depth in another section of this chapter.

Mexican War for Independence and Latin American Revolutions

As described in chapter 3, Spanish American society was based on a small aristocracy of ethnic Spanish peninsulares (people born on the Iberian peninsula) and creoles (people of Spanish descent born in the colonies) ruling large populations of mestizo (mixed) populations, American indigenous, and enslaved people. Like the leaders of the American Revolution, many of these colonial aristocrats felt the priorities of their rulers in Spain did not match their own. Napoleon’s removal of the hereditary king and installation of his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish throne in 1807 removed the last shred of doubt. Soon after Joseph Bonaparte took the throne, representative juntas (local governors) were established in Caracas, Santiago, Buenos Aires, and Bogota to rule in the name of the deposed Spanish king.

King Ferdinand VII was the Spanish monarch who had been forced to abdicate in 1808 in favor of Joseph Bonaparte. Ferdinand regained the throne in 1813, but quickly became known as el Rey Felón, the criminal king. He rejected the liberal 1812 Constitution that had been adopted by Spain’s rebel government during his absence. Historians have described him as “the basest king in Spanish history. Cowardly, selfish, grasping, suspicious, and vengeful, [he] seemed almost incapable of any perception of the commonwealth. He thought only in terms of his power and security and was unmoved by the enormous sacrifices of Spanish people to retain their independence and preserve his throne.” Latin American juntas and the Mexican rebels decided he did not deserve their allegiance and began fighting for their independence from Spain.

In 1810, a creole priest named Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla began Mexico’s revolutionary movement, by giving a speech known as the “Grito de Dolores” or simply El Grito, the Cry. Hidalgo raised an army of 100,000 men, largely of landless peasants anxious for social reform, but they were defeated in January 1811 by a professional army of about 6,000 Spanish troops. Hidalgo was convicted of treason against Spain and executed. Another (this time mestizo) priest named José Maria Morelos took over the insurrection and convened a Congress in 1813 that wrote a constitution for Mexico called the Decreto Constitucional para la Libertad de la America Mexica which declared Mexico’s independence. Unlike later independence movements in South America, Mexico’s demanded not just political but also social change. Figure 4.3.4 is a broadsheet, shown with drawings of skulls and skeletons along the border, with Spanish lyrics of a ballad (corrido) dedicated to Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, who is considered the father of modern Mexico, and honored like George Washington in the United States, with statues, street names, and murals.

The royal government sent a general named Agustín de Iturbide against Guerrero’s forces in Mexico, but Guerrero beat Iturbide on the battlefield and then convinced him to join the revolution. In 1821 the two allied under the Plan de Iguala, or the “Plan of the Three Guarantees,” which proclaimed Mexico’s independence and declared that “All inhabitants . . . without distinction of their European, African or Indian origins are citizens . . . with full freedom to pursue their livelihoods according to their merits and virtues.” When Iturbide declared himself emperor of Mexico, Guerrero and his supporters rebelled and although Iturbide defeated them in the field, he resigned and went into exile when Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna also rebelled. Both Iturbide and Guerrero ended up being executed in their turns as a result of their separate rebellions.

Like the American Revolution, Hidalgo’s revolt sparked similar desires for independence from Spain and Portugal in other Latin American countries. Although other countries had been granted independence prior to the Mexican Revolution, but it was this particular action that inspired forceful evacuation of Spanish and Portuguese control from large portions of the American continents. In 1811, Venezuela and Paraguay both declared their independence from Spain. In 1816 Argentina declared its independence, followed quickly by Chile and Gran Colombia. King Pedro of Portugal, whose father had fled to Brazil in 1807 to avoid being deposed by Napoleon, declared Brazil a constitutional empire under his rule in 1822. In 1824, the Venezuelan Simón Bolívar, who had led the liberation of Gran Colombia, conclusively defeated the Spanish armies at Junín and Sucre, and Peru gained its independence. A year later the eastern portion of the old viceroyalty of Peru became a separate country named after the liberator Bolívar: Bolivia.

Gran Colombia was a republic that includes territory now part of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panama, northern Peru, western Guyana, and northwest Brazil. Bolívar was elected President of Gran Colombia from 1819 to 1830. He hoped Latin America would follow the example of the United States and create a federal union of all the newly-independent nations—or at least a common economic market. He convened a Congress of the Americas in the summer of 1826, inviting all the nations of Latin America and also the United States. The U.S. President, John Quincy Adams, didn’t have a very high opinion of Latin Americans. However, he was an opponent of slavery and almost all of the new Spanish America republics had immediately outlawed the slave trade and had either abolished slavery or had initiated its gradual disappearance through manumission. The only holdout was the independent Brazilian Empire, which did not formally end the enslavement of people of color until 1888, the last nation in the Americas to do so. Adams had been instrumental in promulgating the Monroe Doctrine in 1823, establishing the Western Hemisphere as a region under the protection of the US and warning European nations, especially Great Britain, to limit their activities in the Americas.

- What is happening in this picture? Who are the “victims” and who are the “aggressors”?

- Given the views expressed by the colonists earlier, why would the author use a European stereotyped view of the indigenous peoples to express the victimization of the Loyalists?

- Who might this cartoon be speaking to? Who is the audience?

- Why did the cartoon’s author depict this scene the way that they did? What is the message the author might be trying to send?