17.6: The Ming Dynasty

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 264046

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Painting under the Ming Dynasty

During the Ming Dynasty, Chinese painting developed from the achievements of the earlier Song and Yuan Dynasties.

Learning Objectives

Identify the time period and innovations of the Zhe, Yuanti, Wu, Wongjang, and Huating Schools of painting during the Ming dynasty

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Compared to earlier styles , the Ming Dynasty saw the use of more colors, the development of new painting skills and techniques, and the advancement of calligraphy within paintings.

- The first dominant Ming style was called the Zhe School ; however, later conditions led to the rise of the Wu School, a somewhat subversive style that revived the ideal of the inspired scholar-painters in Ming China.

- The Zhe School and Yuanti School began to prosper during the early Ming period, while the painting schools of the Yuan dynasty began to decline.

- Both the Zhe and Yuanti Schools declined during the mid-Ming period while the Wu School prospered, inheriting and further developing the Yuan scholar-artist style of painting.

- The Wu School painters Tang Yin, Wen Zhengming, Shen Zhou, and Qiu Ying were regarded as the “Four Masters” of the Ming period.

- The late Ming period witnessed the rise of the Songjiang School and Huating School, both of which contributed to the development of the Shanghai School in the late 19th century.

Key Terms

- Songjiang School: A school during the late Ming Dynasty that rivaled Wumen, particularly in generating new theories of painting.

- Yuanti School: A school that was organized and supported by the Ming central government, and served for Ming royal court.

- Zhe School: A school of painters that was part of the Southern School, which thrived during the Ming Dynasty and was known for its formal, academic, and conservative outlook.

Background: The Ming Dynasty

Under the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368), painters had practiced with relative freedom, cultivating a more “individualist” and innovative approach to art that deviated noticeably from the more superficial style of the Song masters who preceded them. However, at the outset of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), the Hongwu emperor (1368–1398) decided to import the existing master painters to his court in Nanjing, where he had the ability to cultivate their styles to conform to the paintings of the Song masters. Hongwu was notorious for his attempts to marginalize and persecute the scholar class, and this was seen as an attempt to banish the gentry’s influence from the arts.

The dominant style of the Ming court painters was called the Zhe School. However, following the ascension of the Yongle emperor (1403–1424), the capital was moved from Nanjing to Beijing, putting a large distance between imperial influence and the city of Suzhou. These new conditions led to the rise of the Wu School of painting, a somewhat subversive style that revived the ideal of the inspired scholar-painters in Ming China.

Painting Styles

During the Ming Dynasty, Chinese painting developed greatly from the achievements of the earlier Song Dynasty and Yuan Dynasty. The painting techniques that were invented and developed before the Ming period became classical during this period. More colors were used in painting during the Ming Dynasty; seal brown, for example, became much more widely used, and sometimes even over-used. Many new painting skills and techniques were innovated and developed, and calligraphy was much more closely and perfectly combined with the art of painting. Chinese painting reached another climax in the mid- to late-Ming Dynasty, when many new schools were born and many outstanding masters emerged.

Development

Early Ming Period (1368–1505)

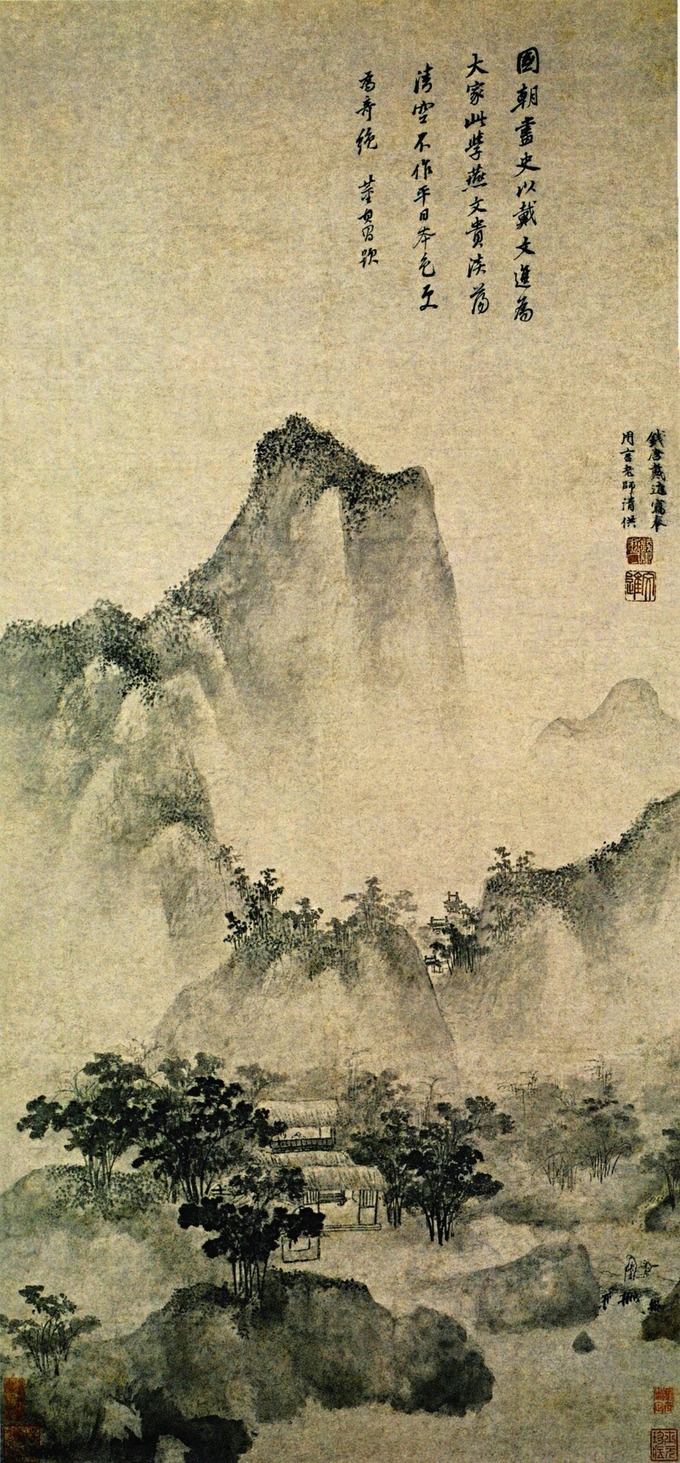

The painting schools of the Yuan Dynasty still heavily influenced early Ming painting, but new schools of painting were also growing. In particular, the Zhe School and the Yuanti School were the dominant schools during the early Ming period. The painters of the Zhe School did not formulate a new distinctive style, preferring instead to further the style of the Southern Song and specializing in large and decorative paintings, most often of landscapes. The school was identified by a formal, academic, and conservative outlook. The Yuanti School was organized and supported by the Ming central government to serve the Ming royal court. Both of these new schools were heavily influenced by the traditions of both the Southern Song painting academy and the Yuan scholar-artists.

Middle Ming Period (1465–1566)

The classical Zhe School and Yuanti School began to decline during the mid-Ming period. Meanwhile, the Wu School (sometimes referred to as Wumen) became the most dominant school nationwide. Its formation is credited to painter Shen Zhou, who is known for using brushstrokes in the tradition of Yuan Dynasty masters. Suzhou, the activity center for Wu School painters, became the biggest center for Chinese painting during this period. The Wumen painters mainly inherited the Yuan scholar-artist style of painting and further developed this style into its peak. The painters Tang Yin, Wen Zhengming, Shen Zhou, and Qiu Ying were regarded as the “Four Masters” of the Ming period.

Often classified as Literati , scholars, or amateur painters (as opposed to professionals), members of the Wu School idealized the concepts of personalizing works and integrating the artists into the art. A Wu School painting is characterized by inscriptions describing the painting, the date, method, and/or reason for the work, which is usually seen as a vehicle for personal expression.

Late Ming Period (1567–1644)

The Songjiang School and Huating School were born and developed toward the end of the Ming Dynasty. The Songjiang School grew to rival the Wu School, particularly in generating new theories of painting. Both the Songjiang and Huating Schools formed the basis for the later Shanghai School in the late 19th century.

The Decorative Arts under the Ming Dynasty

As with many art forms, the Ming Dynasty saw advancement in the realm of decorative arts such as porcelain and lacquerware.

Learning Objectives

Discuss the advancements in Chinese porcelain during the Ming dynasty

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- In Ming China, carved designs in lacquerwares and designs glazed onto porcelain wares displayed intricate scenes similar in complexity to those in painting.

- Elaborate decorative items could be found in the homes of the wealthy alongside embroidered silks, rosewood furniture, feathery latticework, and wares of jade , ivory , and cloisonné. The major production centers for porcelain items in the Ming Dynasty were Jingdezhen in the Jiangxi province and Dehua in the Fujian province.

- The Dehua porcelain factories catered to European tastes by creating Chinese export porcelain by the 16th century.

- Connoisseurship in the late Ming period centered around these items of refined artistic taste, which provided work for art dealers and even underground scam artists who made fake imitations of originals.

Key Terms

- Ming Dynasty: The ruling dynasty of China for 276 years (1368–1644), following the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty; the last dynasty in China ruled by the ethnic Han Chinese.

- cloisonne: A decorative technique for metalwork, especially brass, whereby colored enamel is baked between raised ridges of the metal.

- lacquerwares: Objects (including boxes, tablewares, buttons, etc.) decoratively covered with a clear or colored wood finish that dries by solvent evaporation or a curing process and produces a hard, durable finish; the finish is sometimes inlaid or carved.

- porcelain: A hard, white, translucent ceramic that is made by firing kaolin and other materials.

Overview: Decorative Arts in China

The art form that the post-Renaissance West calls the decorative arts is extremely important in Chinese art. Most of the finest decorative arts were produced in large workshops or factories by essentially unknown artists, especially in the field of Chinese porcelain. Much of the best work in ceramics , textiles, and other techniques was produced over a long period by the various Imperial factories or workshops. In addition to being used by the court, these works were distributed internally and abroad on a huge scale to demonstrate the wealth and power of the Emperors. In contrast , the tradition of ink wash painting, practiced primarily by scholar-officials, developed aesthetic values similar to those of the West while long pre-dating their development there.

The Ming Dynasty

As in earlier dynasties, the Ming Dynasty saw a flourishing in the arts, whether it was painting, poetry, music, literature, or dramatic theater. In the decorative arts, carved designs in lacquerwares and designs glazed onto porcelain wares displayed intricate scenes similar in complexity to those in painting. These items could be found in the homes of the wealthy alongside embroidered silks and wares of jade, ivory, and cloisonné. The houses of the rich were also furnished with rosewood furniture and feathery latticework. The writing materials in a scholar’s private study, including elaborately carved brush holders made of stone or wood, were all designed and arranged ritually to give an aesthetic appeal.

The major production centers for porcelain items in the Ming Dynasty were Jingdezhen in the Jiangxi province and Dehua in the Fujian province. By the 16th century, the Dehua porcelain factories catered to European tastes by creating Chinese export porcelain. Individual potters also became known, such as He Chaozong, who became famous in the early 17th century for his style of white porcelain sculpture . Scholars estimate that about 16% of late Ming era Chinese ceramic exports were sent to Europe, while the rest were destined for Japan and South East Asia. Beginning in the Ming Dynasty, ivory began to be used for small statuettes of the gods and others.

Connoisseurship in the late Ming period centered around these items of refined artistic taste, which provided work for art dealers and even underground scam artists who made fake imitations of originals and false attributions to works of art. However, there were guides to help the wary new connoisseur; in Liu Tong’s book printed in 1635, he told his readers various ways to differentiate between fake and authentic pieces of art. He revealed that a Xuande era (1426–1435) bronzework could be authenticated if one knew how to judge its sheen; porcelain wares from the Yongle era (1402–1424) could be similarly judged by their thickness.

Architecture and Urban Planning under the Ming Dynasty

Chinese urban planning and architecture under the Ming Dynasty are based on fengshui geomancy and numerology, as seen in the Forbidden City.

Learning Objectives

Describe how fengshui and numerology influenced the architecture and urban planning of the Ming Dynasty, as seen in the capital of Beijing

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Chinese urban planning is based on fengshui geomancy and the well-field system of land division.

- Fengshui geomancy is a way of orienting buildings in an auspicious manner based on a number of elements; an auspicious site could be determined by reference to local features such as bodies of water, stars, or a compass.

- In the well-field system of land division, a square area of land is divided into nine identically-sized sections; the eight outer sections were privately cultivated by serfs, while the center section was communally cultivated on behalf of the landowning aristocrat.

- Numerology heavily influenced Imperial architecture, hence the use of nine in much of construction (nine being the greatest single digit number).

- The Forbidden City was the Chinese imperial palace from 1420 to 1912. It is located in the center of Beijing and served as the home of emperors and their households as well as the ceremonial and political center of Chinese government.

- The palace complex exemplifies traditional Chinese palatial architecture and has influenced cultural and architectural developments in East Asia and elsewhere.

Key Terms

- numerology: The study of the purported mystical relationship between numbers and the character or action of physical objects and living things.

- Forbidden City: The palace of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, which is now preserved as a museum in Beijing, China.

- fengshui: A Chinese philosophical system of harmonizing with the surrounding environment; it is closely linked to Daoism.

Chinese Architecture and Urban Planning After 1279

Fengshui Geomancy

Chinese urban planning is based on fengshui geomancy and the well-field system of land division, both used since the Neolithic age. Fengshui geomancy is a way of orienting buildings in an auspicious manner based on a number of elements. Depending on the particular style of fengshui being used, an auspicious site could be determined by reference to local features such as bodies of water, stars, or a compass. The importance of the East (the direction of the rising sun) in orienting and siting Imperial buildings is a form of solar worship found in many ancient cultures , where there is the notion of Ruler being affiliated with the Sun.

The Well-field System and Numerology

The well-field system of land division is a system in which a square area of land is divided into nine identically-sized sections; the eight outer sections were privately cultivated by serfs, while the center section was communally cultivated on behalf of the landowning aristocrat. The basic well-field diagram is overlaid with the luoshu, a magic square divided into 9 sub-squares and linked with Chinese numerology.

Numerology heavily influenced Imperial architecture, as seen in the use of nine in much of construction (nine being the greatest single digit number). It is a common myth, for example, that there are 9,999 rooms and antechambers in the Forbidden City in Beijing—just short of the mythical 10,000 rooms in Heaven; however, this is based on oral tradition and is not supported by survey evidence.

Beijing and the Forbidden City

Beijing became the capital of China after the Mongol invasion of the 13th century, completing the easterly migration of the Chinese capital begun in the earlier Jin dynasty . The Ming uprising in 1368 reasserted Chinese authority and fixed Beijing as the seat of imperial power for the next five centuries.

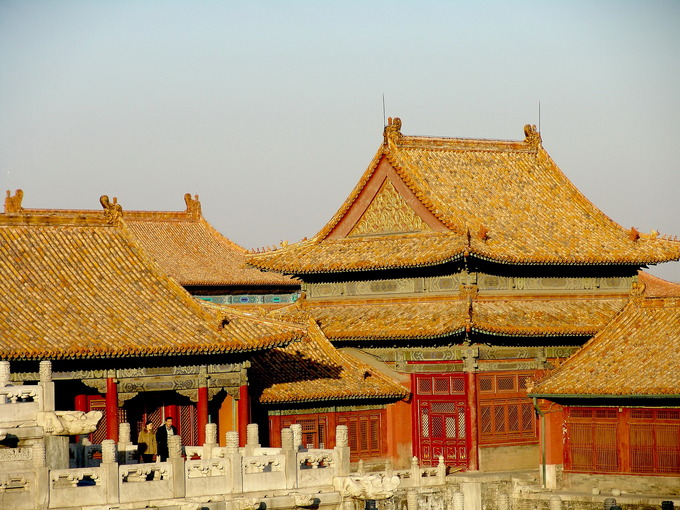

The Forbidden City was the Chinese imperial palace from the Ming Dynasty to the end of the Qing Dynasty—the years 1420 to 1912. It is located in the center of Beijing and served as the home of emperors and their households as well as the ceremonial and political center of Chinese government for almost 500 years. Constructed from 1406 to 1420, the complex consists of 980 buildings and covers 180 acres. The palace complex exemplifies traditional Chinese palatial architecture and has influenced cultural and architectural developments in East Asia and elsewhere. Traditionally, the Emperor and Empress lived in palaces on the central axis of the Forbidden City, while the Crown Prince lived at the eastern side and the concubines lived toward the back (leading to the reference of the numerous imperial concubines as the “Back Palace Three Thousand”). Later, during the mid-Qing Dynasty, the Emperor’s residence was moved to the western side of the complex.

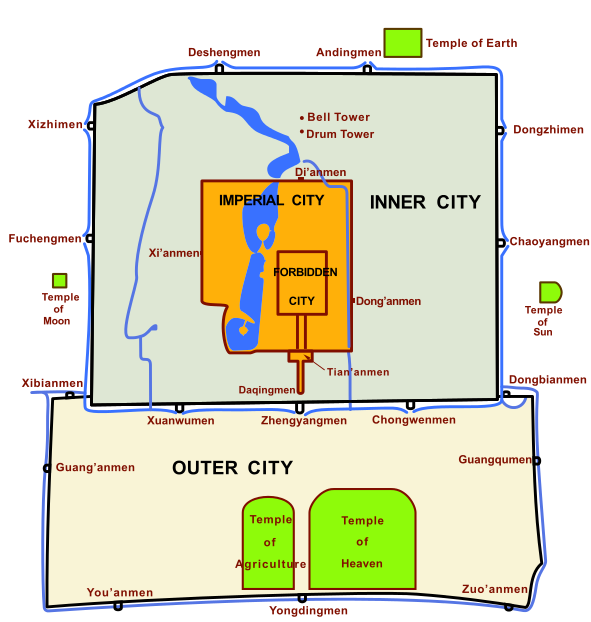

The Forbidden City is a rectangle, measuring 961 meters from north to south and 753 meters from east to west. It consists of 980 surviving buildings with 8,886 bays of rooms. The Forbidden City remains important in the civic scheme of Beijing, with its central north-south axis remaining the central axis of the entire city. The Forbidden City is located within the larger Imperial City in Beijing, which is in turn encompassed by the Inner City. Its axis extends to the south through Tiananmen gate to Tiananmen Square, the ceremonial center of the People’s Republic of China, and on to Yongdingmen. To the north, it extends through Jingshan Hill to the Bell and Drum Towers. This axis is not exactly aligned north-south but is instead tilted by slightly more than two degrees. Researchers now believe the axis was designed in the Yuan Dynasty to be aligned with Xanadu, the other capital of their empire.

Symbolic Design

The design of the Forbidden City, from its overall layout to the smallest detail, was meticulously planned to reflect philosophical and religious principles and the majesty of Imperial power. Some noted examples of symbolic designs include:

- The use of yellow, the color of the Emperor. Almost all roofs in the Forbidden City bear yellow glazed tiles, with only two exceptions. The library at the Pavilion of Literary Profundity has black tiles because black was associated with water, and thus fire prevention; similarly, the Crown Prince’s residences have green tiles because green was associated with wood, and thus growth.

- The use of numerology. The main halls of the Outer and Inner courts, for example, are all arranged in groups of three in the shape of the Qian triagram, representing Heaven. The residences of the Inner Court, on the other hand, are arranged in groups of six in the shape of the Kun triagram, representing the Earth.

- The use of statuettes to indicate importance. The sloping ridges of building roofs are decorated with a line of statuettes led by a man riding a phoenix and followed by an imperial dragon. The number of statuettes represents the status of the building; for example, a minor building might have only 3 or 5, while the Hall of Supreme Harmony is the only building to have 10.

- The layout of buildings. The layout follows ancient customs laid down in the Classic of Rites (a collection of texts describing the social forms, administration, and ceremonial rites of the earlier Zhou dynasty). Thus, ancestral temples are in front of the palace, storage areas are placed in the front part of the palace complex, and residences are placed in the back.

Chinese Literati Expressionism under the Ming Dynasty

Literati Expressionism in Chinese painting was produced by scholar-bureaucrats of the Southern School, rather than by professional painters.

Learning Objectives

Differentiate the literati Southern School of Chinese painting from its professional counterpart in the North

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Under the Ming Dynasty , Chinese culture bloomed. Narrative painting, with a wider color range and a much busier composition than the Song paintings, was immensely popular during the time.

- The Southern School of Chinese painting, often known as ” literati painting,” is a term used to denote art and artists that stand in opposition to the formal Northern School of painting. Southern School painters generally worked in monochrome ink, focused on expressive brushstrokes, and used a more impressionistic approach than the Northern School’s formal attention to detail, use of color, and highly refined traditional modes and methods.

- Literati paintings are most commonly of landscapes featuring men in retirement or travelers admiring the scenery or immersed in culture. Figures are often depicted residing in isolated mountain hermitages .

- Calligraphic inscriptions, either of classical poems or ones composed by a contemporary literati (typically the painter or a friend), are also quite common in these paintings.

Key Terms

- Southern School: A style of Chinese literati painting formed during the Ming Dynasty in opposition to the formal Northern School of painting; led by scholar-bureaucrats, who had either retired from the professional world or had never been a part of it.

- Confucianism: A Chinese ethical and philosophical system developed from the teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucious.

Overview: The Southern School and Literati Painting

Under the Ming Dynasty, Chinese culture bloomed. Narrative painting, with a wider color range and a much busier composition than the previous paintings of the Song Dynasty, was immensely popular during the time.

The Southern School of Chinese painting, often known as “literati painting,” is a term used to denote art and artists that stand in opposition to the formal Northern School of painting. Where formal and professional painters were classified as Northern School, scholar-bureaucrats, who had either retired from the professional world or who had never been a part of it, constituted the Southern School.

History

Never a formal school of art in the sense of artists training under a single master in a single studio, the Southern School is more of an umbrella term spanning a great breadth across both geography and chronology. The literati lifestyle and attitude, as well as the associated style of painting, can be said to go back to early periods of Chinese history. However, the coining of the term “Southern School” is said to have been made by the scholar-artist Dong Qichang (1555–1636), who borrowed the concept from Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism , which also has Northern and Southern Schools.

The Literati Style and Artists

Generally, Southern School painters worked in monochrome ink, focused on expressive brushstrokes, and used a somewhat more impressionistic approach than the Northern School’s formal attention to detail, use of color, and highly refined traditional modes and methods. The stereotypical literati painter lived in retirement either in the mountains or other rural areas, not entirely isolated but immersed in natural beauty and far from mundane concerns. These artists tended to be lovers of culture, enjoying and taking part in all Four Arts of the Chinese Scholar (painting, calligraphy , music, and games of skill and strategy) as touted by Confucianism . Many artists would combine these elements into their work and would gather with one another to share their interests.

Literati paintings are most commonly of landscapes, often of the shanshui (“mountain water”) genre . Many feature scholars in retirement or travelers admiring the scenery or immersed in culture. Figures are often depicted carrying or playing guqin (a plucked seven-string Chinese musical instrument of the zither family) and residing in quite isolated mountain hermitages. Calligraphic inscriptions, either of classical poems or ones composed by a contemporary literati (typically the painter or a friend), are also quite common. While this sort of landscape with certain features and elements is the standard stereotypical Southern School painting, the genre actually varied quite widely in rejecting the formal strictures of the Northern School. The painters sought the freedom to experiment with subjects and styles.

Like other traditions in Chinese art, the early Southern style soon acquired a classic status and was often copied and imitated, with later painters sometimes producing sets of paintings each in the style of a different classic artist. Though greatly affected by the confrontation with Western painting from the 18th century on, the style continued to be practiced until at least the 20th century.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Dai Jin-Landscape in the Style of Yan Wengui. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dai_Jin-Landscape_in_the_Style_of_Yan_Wengui.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Zhe school (painting). Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Zhe_school_(painting). License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Shen Zhou. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Shen_Zhou. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ming Dynasty painting. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ming_Dynasty_painting. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Zhe School. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Zhe%20School. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Yuanti School. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuanti%20School. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Songjiang School. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Songjiang%20School. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Wu School. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Wu_School. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- B-ChinesischeLackdose. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:B-ChinesischeLackdose.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- China ming blue dragons. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:China_ming_blue_dragons.JPG. License: CC BY: Attribution

- Ming Dynasty. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ming_Dynasty%23Urban_and_rural_life. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chinese art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- porcelain. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/porcelain. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- lacquerwares. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/lacquerwares. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ming Dynasty. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ming%20Dynasty. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- cloisonne. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/cloisonne. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Beijing-forbidden7. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Beijing-forbidden7.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- HighStatusRoofDeco.jpg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Forbidden_City#/media/File:HighStatusRoofDeco.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Gugun panorama-2005-1. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gugun_panorama-2005-1.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 591px-Beijing_city_wall_map_vectorized.svg.png. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Forbidden_City#/media/File:Beijing_city_wall_map_vectorized.svg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Forbidden City. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Forbidden_City. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ancient Chinese urban planning. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ancient_Chinese_urban_planning. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Chinese architecture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_architecture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Fengshui. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Fengshui. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Luoshu. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Luoshu. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- numerology. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/numerology. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Wen Zhengming painting. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Wen_Zhengming_painting.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Lofty Mt.Lu by Shen Zhou. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lofty_Mt.Lu_by_Shen_Zhou.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Wanluan Thatched Hall by Dong Qichang. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Wanluan_Thatched_Hall_by_Dong_Qichang.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Chinese art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_art%23Yuan_painting. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Southern School. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Southern_School. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Wu School. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Wu_School. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Dong Qichang. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Dong_Qichang. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Southern School. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Southern%20School. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Confucianism. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Confucianism. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike