13.9: The Early Middle Ages

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 264003

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages began with the fall of the Roman Empire and ended in the early 11th century; its art encompasses vast and divergent forms of media.

Learning Objectives

Identify the major periods and styles into which European art of the Early Middle Ages is classified, and artistic elements common to all of them

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- “Medieval art” applies to various media , including sculpture, illuminated manuscripts , tapestries , stained glass, metalwork , and mosaics .

- Early medieval art in Europe is an amalgamation of the artistic heritage of the Roman Empire, the early Christian church, and the “barbarian” artistic culture of Northern Europe.

- Despite the wide range of media, the use of valuable and precious materials is a constant in medieval art. Many artworks feature the lavish use of gold, jewels, expensive pigments , and other precious goods.

- A rise in illiteracy during the Early Middle Ages resulted in the need for art to convey complex narratives and symbolism . As a result, art became more stylized , losing the classical naturalism of Graeco-Roman times, for much of the Middle Ages.

- Few large stone buildings were constructed between the Constantinian basilicas of the fourth and eighth centuries. By the late eighth century, the Carolingian Empire revived the basilica form of architecture.

The Middle Ages of the European world covers approximately 1,000 years of art history in Europe, and at times extended into the Middle East and North Africa. The Early Middle Ages is generally dated from the fall of the Western Roman Empire (476 CE) to approximately 1000, which marks the beginning of the Romanesque period. It includes major art movements and periods, national and regional art, genres , and revivals. Art historians attempt to classify medieval art into major periods and styles with some difficulty, as medieval regions frequently featured distinct artistic styles such as Anglo-Saxon or Norse . However, a generally accepted scheme includes Early Christian art, Migration Period art, Byzantine art, Insular art , Carolingian art, Ottonian art, Romanesque art , and Gothic art, as well as many other periods within these central aesthetic styles.

Population decline, relocations to the countryside, invasion, and migration began in Late Antiquity and continued in the Early Middle Ages. The large-scale movements of the Migration Period, including various Germanic peoples, formed new kingdoms in what remained of the Western Roman Empire. In the West, most kingdoms incorporated the few extant Roman institutions. Monasteries were founded as campaigns to Christianize pagan Europe continued. The Franks, under the Carolingian dynasty , briefly established the Carolingian Empire during the later eighth and early ninth century. It covered much of Western Europe but later succumbed to the pressures of internal civil wars combined with external invasions—Vikings from the north, Hungarians from the east, and Saracens from the south.

As literacy declined and printed material became available only to monks and nuns who copied illuminated manuscripts, art became the primary method of communicating narratives (usually of a Biblical nature) to the masses . Conveying complex stories took precedence over producing naturalistic imagery , leading to a shift toward stylized and abstracted figures for most of the Early Middle Ages. Abstraction and stylization also appeared in imagery accessible only to select communities, such as monks in remote monasteries like the complex at Lindisfarne off the coast of Northumberland, England.

Early medieval art exists in many media. The works that remain in large numbers include sculpture, illuminated manuscripts, stained glass, metalwork, and mosaics, all of which have had a higher survival rate than fresco wall-paintings and works in precious metals or textiles such as tapestries. In the early medieval period, the decorative arts, including metalwork, ivory carving, and embroidery using precious metals, were probably more highly valued than paintings or sculptures. Metal and inlaid objects, such as armor and royal regalia (crowns, scepters, and the like) rank among the best-known early medieval works that survive to this day.

Early medieval art in Europe grew out of the artistic heritage of the Roman Empire and the iconographic traditions of the early Christian church. These sources were mixed with the vigorous “Barbarian” artistic culture of Northern Europe to produce a remarkable artistic legacy. The history of medieval art can be seen as an ongoing interplay between the elements of classical, early Christian, and “barbarian” art. Apart from the formal aspects of classicism, there was a continuous tradition of realistic depiction that survived in Byzantine art of Eastern Europe throughout the period. In the West realistic presentation appears intermittently, combining and sometimes competing with new expressionist possibilities. These expressionistic styles developed both in Western Europe and in the Northern aesthetic of energetic decorative elements.

Monks and monasteries had a deep effect on the religious and political life of the Early Middle Ages, in various cases acting as land trusts for powerful families, centers of propaganda and royal support in newly conquered regions, and bases for missions and proselytizing. They were the main and sometimes only regional outposts of education and literacy. Many of the surviving manuscripts of the Latin classics were copied in monasteries in the Early Middle Ages. Monks were also the authors of new works, including history, theology, and other subjects written by authors such as Bede (died 735), a native of northern England who wrote in the late seventh and early eighth centuries.

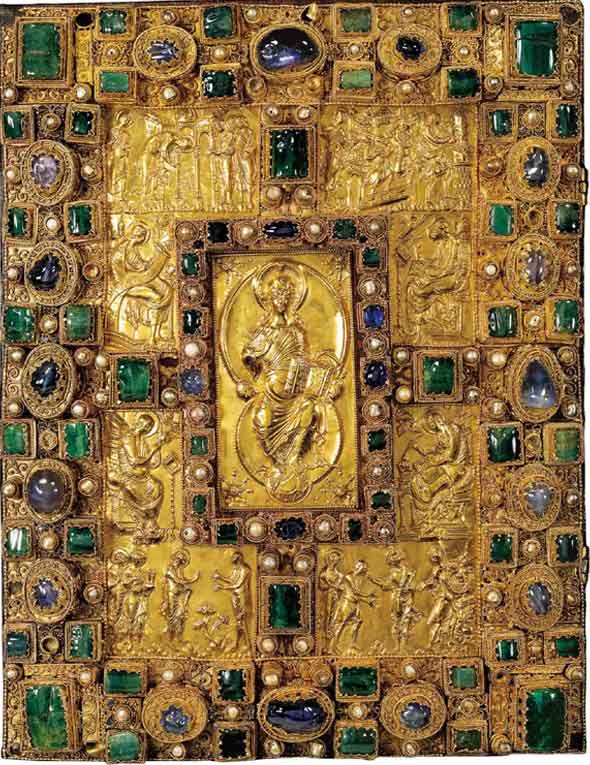

The use of valuable materials is a constant in medieval art. Most illuminated manuscripts of the Early Middle Ages had lavish book covers decked with precious metal, ivory, and jewels. One of the best examples of precious metalwork in medieval art is the jeweled cover of the CodexAureus of St. Emmeram (c. 870). The Codex, whose origin is unknown, is decorated with gems and gold relief . Gold was also used to create sacred objects for churches and palaces, as a solid background for mosaics, and applied as gold leaf to miniatures in manuscripts and panel paintings. Named after Emmeram of Regensburg and lavishly illuminated, the Codex is an important example of Carolingian art, as well of one of very few surviving treasure bindings of the late ninth century.

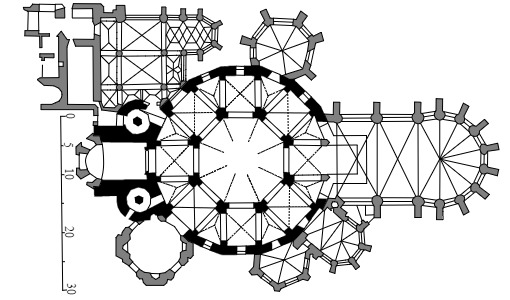

Few large stone buildings were constructed between the Constantinian basilicas of the fourth and eighth centuries, although many smaller ones were built during the sixth and seventh centuries. By the early eighth century, the Merovingian dynasty revived the basilica form of architecture. One feature of the basilica is the use of a transept , the “arms” of a cross-shaped building that are perpendicular to the long nave . Other new features of religious architecture include the crossing tower and a monumental entrance to the church, usually at the west end of the building.

Architecture under the Merovingians

Merovingian architecture emerged under the Merovingian Frankish dynasty and reflected a fusion of Western and Eurasian influences.

Learning Objectives

Describe some basic elements of Merovingian architecture

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Merovingian architecture often continued the Roman basilica tradition, but also adopted influences from as far away as Syria and Armenia.

- Many Merovingian churches no longer exist. One surviving church is Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains at Metz, originally built as a Roman gymnasium in the late fourth century and reappropriated into a church in the mid-eighth century.

- Some small Merovingian structures remain, especially baptisteries, which were spared rebuilding in later centuries.

- The Baptistery at Saint-Leonce of Fréjus, highlights the influence of Syrian technique on Merovingian architecture, evidenced by its octagonal shape and a covered cupola on pillars . On the other hand, St. Jean at Poitiers is very different from the Baptistery at Saint-Leonce of Fréjus, as it has the form of a rectangle flanked by three apses .

- Although mostly reconstructed, the interior of the baptistery of Saint-Sauveur reveals the influence of Roman architecture on Merovingian architects.

Key Terms

- the Baptistery at Saint-Leonce of Fréjus: A structure that highlights the influence of Syrian technique on Merovingian architecture.

- the basilica of Saint Martin at Tours: One of the most famous examples of Merovingian church architecture, built at the beginning of the dynasty’s reign.

- Merovingian dynasty: A Frankish family who ruled parts of present-day France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and parts of Germany from the mid-fifth century to the mid-eighth century.

Merovingian architecture developed under the Merovingian dynasty , a Frankish family who ruled parts of present-day France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and parts of Germany from the mid-fifth century to the mid-eighth century. The advent of the Merovingian dynasty in Gaul led to important changes in architecture.

The unification of the Frankish kingdom under Clovis I (465–511) and his successors corresponded with the need for new churches. Merovingian architecture often continued the Roman basilica tradition, but also adopted influences from as far away as Syria and Armenia. In the East, most structures were in timber , but stone was more common for significant buildings in the West and in the southern areas that later fell under Merovingian rule.

Many Merovingian churches no longer exist. One famous example is the basilica of Saint Martin at Tours, at the beginning of Merovingian rule and at the time on the edge of Frankish territory. According to scholars, the church had 120 marble columns , towers at the east end, and several mosaics . A feature of the basilica of Saint-Martin that became a hallmark of Frankish church architecture was the sarcophagus or reliquary of the saint, raised to be visible and sited axially behind the altar, sometimes in the apse. There are no Roman precedents for this Frankish innovation. A number of other buildings now lost, including the Merovingian foundations of Saint-Denis, St. Gereonin Cologne, and the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris, are described as similarly ornate.

One surviving church is Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains at Metz. The building was originally built in 380 CE as a gymnasium (a European type of school) for a Roman spa complex. In the seventh century, the structure was converted into a church, becoming the chapel of a Benedictine convent. The structure bears common hallmarks of a Roman basilica, including the round arches and tripartite division into nave (center) and aisles (left and right of the nave), a division visible from the exterior of the building. Apparently missing, however, is the apse.

Other major churches have been rebuilt, usually more than once. However, some small Merovingian structures remain, especially baptisteries, which were spared rebuilding in later centuries. For instance, the Baptistery at Saint-Leonce of Fréjus, highlights the influence of Syrian technique on Merovingian architecture, evidenced by its octagonal shape and covered cupola on pillars.

By contrast , St. Jean at Poitiers has the form of a rectangle flanked by three apses. The original building has probably had a number of alterations but preserves traces of Merovingian influence in its marble capitals .

The baptistery of Saint-Sauveur at Aix-en-Provence was built at the beginning of the sixth century, at about the same time as similar baptisteries in Fréjus Cathedral and Riez Cathedral in Provence, in Albenga, Liguria, and in Djémila, Algeria. Only the octagonal baptismal pool and the lower part of the walls remain from that period. The other walls, Corinthian columns, arcade , and dome were rebuilt in the Renaissance . A viewing hole in the floor reveals the bases of the porticoes of the Roman forum under the baptistery.

By the seventh century, Merovingian craftsmen were brought to England for their glass-making skills, and Merovingian stonemasons were used to build English churches, suggesting that the culture’s ornamental arts were highly regarded by neighboring peoples.

Anglo-Saxon and Irish Art

Celtic and Anglo-Saxon art display similar aesthetic qualities and media, including architecture and metalwork.

Learning Objectives

Compare elements of Anglo-Saxon and Celtic art

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- Anglo-Saxon art emerged when the Anglo-Saxons migrated from the continent in the fifth century and ended in 1066 with the Norman Conquest. Anglo-Saxon art, which favored brightness and color, survives mostly in architecture and metalwork .

- The Sutton Hoo burial site contains the best known examples of Anglo-Saxon metalwork, showing the masterful craftsmanship of items such as armor and ornamental objects.

- The architectural character of Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical buildings range from influence from Celtic and Early Christian styles . Later Anglo-Saxon architecture is characterized by pilasters , blank arcading, baluster shafts and triangular-headed openings.

- Celtic art is ornamental, avoiding straight lines , only occasionally using symmetry , and often involving complex symbolism . Celtic art has used a variety of styles and as shown influences from other cultures in knotwork, spirals, key patterns, lettering, and human figures.

- With the arrival of Christianity, Celtic art was influenced by both Mediterranean and Germanic traditions, creating the Insular style. The interlace patterns that are typical of Celtic art were in fact introduced to Insular art from the Mediterranean and Migration artistic traditions.

Key Terms

- Insular Art: Art produced in the post-Roman history of the British Isles, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art. The term derives from the Latin term for island. Britain and Ireland shared a common style that differed from that of the rest of Europe in this period.

Anglo-Saxon art emerged when the Anglo-Saxons migrated from the continent in the fifth century and ended in 1066 with the Norman Conquest. Anglo-Saxon art, which favored brightness and color, survives mostly in architecture and metalwork.

Anglo-Saxon Metalwork

Anglo-Saxon metalwork consisted of Germanic-style jewelry and armor, which was commonly placed in burials. After the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity in the seventh century, the fusion of Germanic Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, and Early Christian techniques created the Hiberno-Saxon style (or Insular art) in the form of sculpted crosses and liturgical metalwork. Insular art is characterized by detailed geometric designs, interlace, and stylized animal decoration.

Anglo-Saxon metalwork initially used the Germanic Animal Style decoration that would be expected from recent immigrants, but gradually developed a distinctive Anglo-Saxon character. For instance, round disk brooches were preferred for the grandest Anglo-Saxon pieces, over continental styles of fibulae and Romano-British penannular brooches. Decoration included cloisonné (“cellwork”) in gold and garnet for high-status pieces. Despite a considerable number of other finds, the discovery of the ship burial at Sutton Hoo transformed the history of Anglo-Saxon art, showing a level of sophistication and quality that was wholly unexpected at this date. Among the most famous finds from Sutton Hoo are a helmet and an ornamental purse lid.

Anglo-Saxon Architecture

Anglo-Saxon secular buildings in Britain were generally simple, constructed mainly using timber with thatch for roofing. No universally accepted example survives aboveground. There are, however, many remains of Anglo-Saxon church architecture. At least fifty churches of Anglo-Saxon origin display the culture’s major architectural features, although in some cases these aspects are small and significantly altered. The round-tower church and tower-nave church are distinctive Anglo-Saxon types. All surviving churches, except one timber church, are built of stone or brick, and in some cases show evidence of reused Roman work.

The architectural character of Anglo-Saxon ecclesiastical buildings range from influence from Celtic and Early Christian styles. Later Anglo-Saxon architecture is characterized by pilasters, blank arcading, baluster shafts and triangular-headed openings. In the final decades of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom a more general Romanesque style was introduced from the Continent, as in the additions to Westminster Abbey made from 1050 onwards.

Celtic Art

“Celtic art” refers to the art of people who spoke Celtic languages in Europe and those with uncertain language but cultural and stylistic similarities with Celtic speakers. Typically, Celtic art is ornamental, avoiding straight lines, only occasionally using symmetry, and often involving complex symbolism. Celtic art has used a variety of styles and has shown influences from other cultures in knotwork, spirals, key patterns, lettering, and human figures.

Around 500 BCE, the La Tène style appeared rather suddenly, coinciding with some kind of societal upheaval that involved a shift of the major centers to the northwest. La Tène was especially prominent in northern France and western Germany, but over the next three centuries the style spread as far as Ireland, Italy, and modern Hungary. Early La Tène style adapted ornamental motifs from foreign cultures, including Scythian, Greek, and Etruscan arts. La Tène is a highly stylized curvilinear art based mainly on classical vegetable and foliage motifs such as leafy palmette forms, vines, tendrils, and lotus flowers together with spirals, S-scrolls, lyre , and trumpet shapes. It remains uncertain whether some of the most notable objects found from the La Tène period were made in Ireland or elsewhere (as far away as Egypt in some cases). But in Scotland and the western parts of Britain, versions of the La Tène style remained in use until it became an important component of the Insular style that developed to meet the needs of newly Christian populations.

Celtic art in the medieval period was produced by the people of Ireland and parts of Britain over the course of 700 years. With the arrival of Christianity, Celtic art was influenced by both Mediterranean and Germanic traditions, primarily through Irish contact with Anglo-Saxons, which resulted in the Insular style. The interlace patterns that are regarded as typical of Celtic art were in fact introduced from the Mediterranean and Migration Period artistic traditions. Specific examples of Celtic Insular art include the Tara Brooch and the Ardagh Chalice.

Catholic Celtic sculpture began to flourish in the form of the large stone crosses that held biblical scenes in carved relief . This art form reached its apex in the early 10th century, with Muiredach’s Cross at Monasterboice and the Ahenny High Cross.

Illustrated Books in the Early Middle Ages

Insular art is often characterized by detailed geometric designs, interlace, and stylized animal decorations in illuminated manuscripts.

Learning Objectives

Describe the history and characteristics of illuminated manuscripts in Insular art

Key Takeaways

Key Points

- An illuminated manuscript features text supplemented by elaborate decoration. The term is mostly used to refer to any decorated or illustrated manuscript from the Western tradition. Illuminated manuscripts were written on vellum , and some feature the use of precious metals and pigments that were imported to northern Europe.

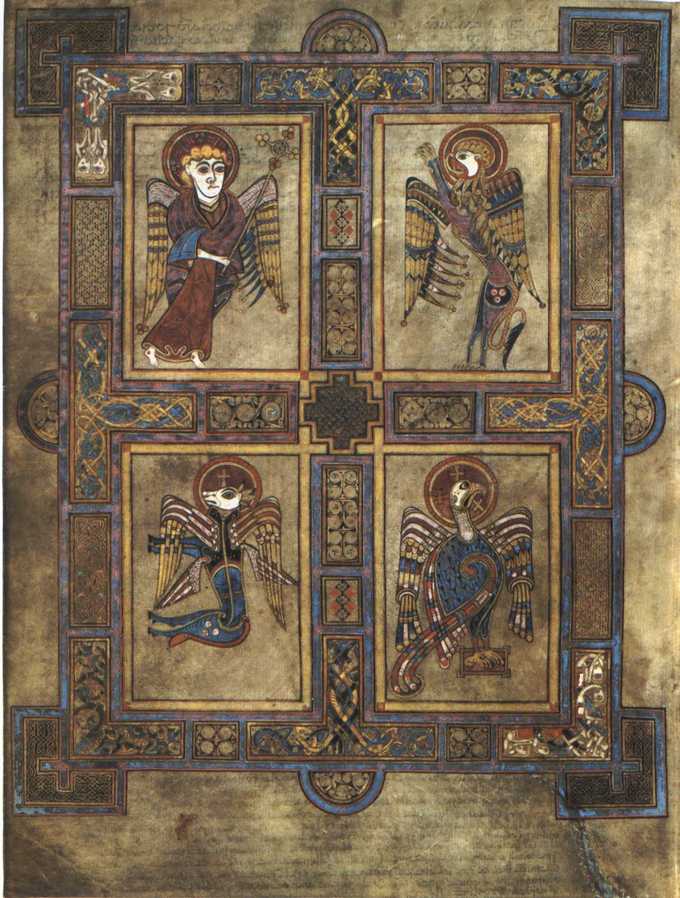

- Insular art is characterized by detailed geometric designs, interlace,

and stylized animal decoration spread boldly across illuminated

manuscripts. Insular manuscripts sometimes take a whole page for a

single initial or the first few words at beginnings of gospels. - TheBook of Kells is considered a masterwork of Western calligraphy , with its illustrations and ornamentation surpassing that of other Insular Gospel books in complexity. The Kells manuscript’s decoration combines traditional Christian iconography with the ornate swirling Insular motifs .

- Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscripts, such as the StockholmCodexAureus, combine Insular art with Italian styles such as classicism.

- Mozarabic art refers to art of Mozarabs, Iberian Christians living in Al-Andalus who adopted Arab customs without converting to Islam during the Islamic invasion of the Iberian peninsula. It features a combination of (Hispano) Visigothic, and Islamic art styles, as in the Beatus manuscripts , which combine Insular art illumination forms with Arabic-influenced geometric designs.

Key Terms

- parchment: A material made from the polished skin of a calf, sheep, goat or other animal, used as writing paper.

- Mozarabic: Art of Iberian Christians living in Al-Andalus, the Muslim-conquered territories, after the Arab invasion of the Iberian Peninsula (711 CE) to the end of the 11th century. These people adopted some Arab customs without converting to Islam, preserving their religion and some ecclesiastical and judicial autonomy.

- Book of Kells: An illuminated manuscript in Latin containing the four Gospels of the New Testament together with various prefatory texts and tables. It was created by Celtic monks circa 800 or slightly earlier.

- Insular Art: Art produced in the post-Roman history of the British Isles, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art. The term derives from the Latin term for island. Britain and Ireland shared a common style that differed from that of the rest of Europe.

- illuminated manuscript: A book in which the text is supplemented by decoration, such as initials, borders (marginalia), and miniature illustrations.

Background

An illuminated manuscript contains text supplemented by the addition of decoration, such as decorated initials, borders (marginalia), and miniature illustrations. In the strict definition of the term, an illuminated manuscript indicates only those manuscripts decorated with gold or silver. However, the term is now used to refer to any decorated manuscript from the Western tradition. The earliest surviving substantive illuminated manuscripts are from the period 400 to 600 CE and were initially produced in Italy and the Eastern Roman Empire. The significance of these works lies not only in their inherent art historical value , but also in the maintenance of literacy offered by non-illuminated texts as well. Had it not been for the monastic scribes of Late Antiquity who produced both illuminated and non-illuminated manuscripts, most literature of ancient Greece and Rome would have perished in Europe.

The majority of surviving illuminated manuscripts are from the Middle Ages , and hence most are of a religious nature. Illuminated manuscripts were written on the best quality of parchment , called vellum. By the sixteenth century, the introduction of printing and paper rapidly led to the decline of illumination, although illuminated manuscripts continued to be produced in much smaller numbers for the very wealthy. Early medieval illuminated manuscripts are the best examples of medieval painting, and indeed, for many areas and time periods, they are the only surviving examples of pre-Renaissance painting.

Insular Art in Illustrated Books

Deriving from the Latin word for island (insula), Insular art is characterized by detailed geometric designs, interlace, and stylized animal decoration spread boldly across illuminated manuscripts. Insular manuscripts sometimes take a whole page for a single initial or the first few words at beginnings of gospels. The technique of allowing decoration the right to roam was later influential on Romanesque and Gothic art. From the seventh through ninth centuries, Celtic missionaries traveled to Britain and brought the Irish tradition of manuscript illumination, which came into contact with Anglo-Saxon metalworking. New techniques employed were filigree and chip-carving, while new motifs included interlace patterns and animal ornamentation.

The Book of Kells (Irish: Leabhar Cheanannais), created by Celtic monks in 800, is an illustrated manuscript considered the pinnacle of Insular art. Also known as the Book of Columba, The Book of Kells is considered a masterwork of Western calligraphy, with its illustrations and ornamentation surpassing that of other Insular Gospel books in extravagance and complexity. The Book of Kells‘s decoration combines traditional Christian iconography with the ornate swirling motifs typical of Insular art. Figures of humans, animals, and mythical beasts, together with Celtic knots and interlacing patterns in vibrant colors, enliven the manuscript’s pages. Many of these minor decorative elements are imbued with Christian symbolism . The manuscript comprises 340 folios made of high-quality vellum and unprecedentedly elaborate ornamentation including 10 full-page illustrations and text pages vibrant with decorated initials and interlinear miniatures. These mark the furthest extension of the anti- classical and energetic qualities of Insular art.

The Insular majuscule script of the text itself in the Book of Kells appears to be the work of at least three different scribes. The lettering is in iron gall ink with colors derived from a wide range of substances, many of which were imported from distant lands. The text is accompanied by many full-page miniatures, while smaller painted decorations appear throughout the text in unprecedented quantities. The decoration of the book is famous for combining intricate detail with bold and energetic compositions . The illustrations feature a broad range of colors, most often purple, lilac, red, pink, green, and yellow. As typical with Insular work, there was neither gold nor silver leaf in the manuscript. However, the pigments for the illustrations, which included red and yellow ochre , green copper pigment (sometimes called verdigris), indigo , and lapis lazuli , were very costly and precious. They were imported from the Mediterranean region and, in the case of the lapis lazuli, from northeast Afghanistan.

The decoration of the first eight pages of the canon tables is heavily influenced by early Gospel Books from the Mediterranean, where it was traditional to enclose the tables within an arcade . Although influenced by this Mediterranean tradition, the Kells manuscript presents this motif in an Insular spirit, where the arcades are not seen as architectural elements but rather become stylized geometric patterns with Insular ornamentation. Further, the complicated knot work and interweaving found in the Kells manuscript echo the metalwork and stone carving works that characterized the artistic legacy of the Insular period.

Anglo-Saxon illuminated manuscripts form a significant part of Insular art and reflect a combination of influences from the Celtic styles that arose when the Anglo-Saxons encountered Irish missionary activity. A different mixture is seen in the opening from the StockholmCodex Aureus, where the evangelist portrait reflects an adaptation of classical Italian style, while the text page is mainly in Insular style, especially the first line with its vigorous Celtic spirals and interlace. This is one of the so-called “Tiberius Group” of manuscripts with influence from the Italian style. It is the last English manuscript in which trumpet spiral patterns are found.

The Beatus Manuscripts

The Commentary on the Apocalypse was originally a Mozabaric eighth-century work by the Spanish monk and theologian Beatus of Liébana. Often referred to simply as the Beatus, it is used today to reference any of the extant manuscript copies of this work, especially any of the 26 illuminated copies that have survived. The historical significance of the Commentary is even more pronounced since it included a world map, offering a rare insight into the geographical understanding of the post-Roman world. Considered together, the Beatus codices are among the most important Spanish and Mozarabic medieval manuscripts and have been the subject of extensive scholarly and antiquarian inquiry.

Though Beatus might have written these commentaries as a response to Adoptionism in the Hispania of the late 700s, many scholars believe that the book’s popularity in monasteries stemmed from the Arabic-Islamic conquest of the Iberian peninsula, which some Iberian Christians took as a sign of the Antichrist. Not all of the Beatus manuscripts are complete, and some exist only in fragmentary form. However, the surviving manuscripts are lavishly decorated in the Mozarabic, Romanesque, or Gothic style of illumination.

Mozarabic art refers to art of Mozarabs, Iberian Christians living in Al-Andalus who adopted Arab customs without converting to Islam during the Islamic invasion of the Iberian peninsula (from the eighth through the 11th centuries). Mozarabic art features a combination of (Hispano) Visigothic and Islamic art styles, as in the Beatus manuscripts, which combine Insular art illumination forms with Arabic-influenced geometric designs.

- Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- AachenChapelDB.svg.png. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Palatine_Chapel,_Aachen#/media/File:AachenChapelDB.svg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Codex Aureus Sankt Emmeram. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Codex_Aureus_Sankt_Emmeram.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- 360px-Lindisfarne_Gospels_folio_209v.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2647377%20. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 487px-CoronaRecesvinto01.jpeg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2432551%20. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Wikipedia. Provided by: Palatine Chapel, Aachen. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Palatine_Chapel,_Aachen. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Lindisfarne Gospels. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Lindisfarne_Gospels. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Middle Ages. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Ages#Early_Middle_Ages. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Medieval Art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Medieval_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Codex Aureus. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex%20Aureus. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Frejuscathedrale. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Frejuscathedrale.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 360px-Baptistere_Saint_Sauveur_by_Malost.JPG. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: upload.wikimedia.org/Wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/66/Baptistere_Saint_Sauveur_by_Malost.JPG/360px-Baptistere_Saint_Sauveur_by_Malost.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 640px-Metz_-_Eglise_Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnais_-_Vue_du_cu00f4tu00e9_Est.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11295607. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 312 Poitiers baptisterio. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:312_Poitiers_baptisterio.JPG. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Basilica of Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilica_of_Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Merovingian Dynasty. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Merovingian_dynasty. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Merovingian Art and Architecture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Merovingian_art_and_architecture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Merovingian Art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Merovingian%20Art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 451px-Sutton_Hoo_helmet_reconstructed.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: upload.wikimedia.org/Wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/26/Sutton_Hoo_helmet_reconstructed.jpg/451px-Sutton_Hoo_helmet_reconstructed.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 450px-Ireland_2010_etc_029_28229.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: upload.wikimedia.org/Wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/dd/Ireland_2010_etc_029_%282%29.jpg/450px-Ireland_2010_etc_029_%282%29.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 640px-Sutton_hoo_28129.JPG. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: upload.wikimedia.org/Wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/17/Sutton_hoo_%281%29.JPG/640px-Sutton_hoo_%281%29.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- 450px-Ahenny_High_Cross_-_geograph.org.uk_-_475968.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: upload.wikimedia.org/Wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a3/Ahenny_High_Cross_-_geograph.org.uk_-_475968.jpg/450px-Ahenny_High_Cross_-_geograph.org.uk_-_475968.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Reculver.jpg. Provided by: Wikimedia. Located at: upload.wikimedia.org/Wikipedia/en/8/8d/Reculver.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- 640px-Fobbing-detail.JPG. Provided by: Wikimedia Commons. Located at: upload.wikimedia.org/Wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ac/Fobbing-detail.JPG/640px-Fobbing-detail.JPG. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Ardagh chalice. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ardagh_chalice.jpg. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Wikipedia. Provided by: Ardagh Hoard. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Ardagh_Hoard. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Sutton Hoo. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Sutton_Hoo. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- La Tu00e8ne Culture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/La_T%C3%A8ne_culture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Anglo-Saxon Architecture. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglo-Saxon_architecture. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Anglo Saxon Art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglo_Saxon_art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Celtic Art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Celtic%20Art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Insular Art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Insular%20Art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- KellsFol292rIncipJohn. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:KellsFol292rIncipJohn.jpg. License: CC BY: Attribution

- beatus-map.jpeg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Beatus_map.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- b-facundus-233vd-c3-a9t.jpeg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:B_Facundus_233vd%C3%A9t.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- ureuscanterburyfolios9v10r.jpeg. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:CodexAureusCanterburyFolios9v10r.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- KellsFol027v4Evang. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:KellsFol027v4Evang.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Beatus Map. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Beatus_map. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Parchment. Provided by: Wiktionary. Located at: en.wiktionary.org/wiki/parchment. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Beatus Manuscripts. Provided by: Boundless Learning. Located at: www.boundless.com/atoms/8329. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Illuminated Manuscripts. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Illuminated_manuscripts. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Book of Kells. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Kells. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Medieval Art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Medieval_art%23Migration_Period_through_Christianization. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Illuminated Manuscript. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/illuminated%20manuscript. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Insular Art. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Insular%20Art. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike